Zoom’s Waiting Room Vulnerability

This research note is a follow-up to our April 3, 2020 report on the confidentiality of Zoom Meetings. In this note, we describe a security issue where users in the “waiting room” of a Zoom meeting could have spied on the meeting, even if they were not approved to join. Zoom fixed the issue after we reported it to them.

Summary

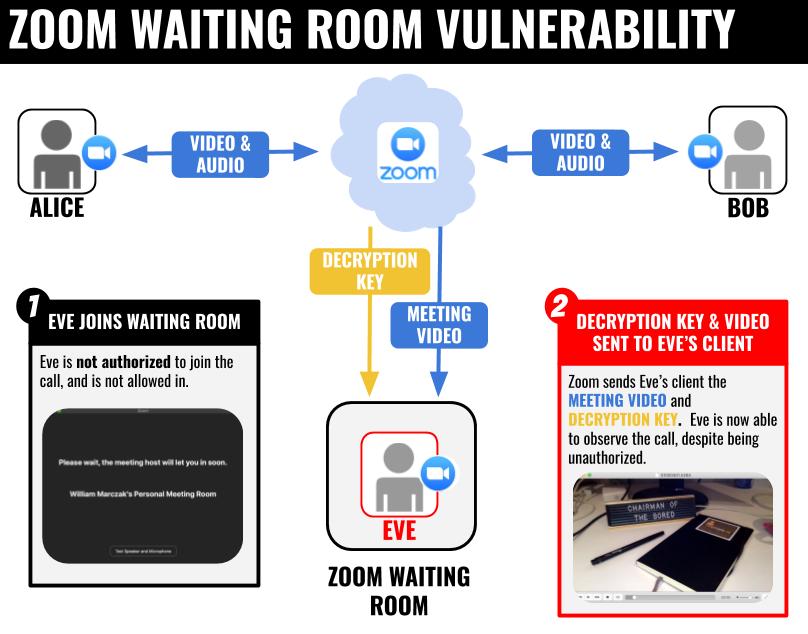

While we were conducting research for our April 3, 2020 report on the confidentiality of Zoom meetings, we uncovered an issue with Zoom’s waiting rooms feature, which we reported to Zoom’s security team on April 2. Before Zoom fixed the issue, Zoom servers would automatically send a live video stream of the meeting, as well as the meeting’s decryption key, to all users in a meeting’s waiting room. Because users in a Zoom waiting room are not yet approved to join the meeting, and Zoom’s documentation appears to promote waiting rooms as a confidentiality feature, we assessed that this issue could represent a security concern.

On April 7, Zoom reported to us that they had implemented a server-side fix for the issue. Zoom also told us that because no customer action or update was required, they would not be requesting a CVE number. On April 8, Zoom’s CEO mentioned during an “Ask Eric Anything” webinar that Zoom had fixed the issue with waiting rooms, and appeared to say of the issue, ”… before the fix…from the server side we did not send audio or video data to the waiting room clients.” Though, in our testing, waiting room users did receive a video stream of the Zoom meeting prior to the fix (Figure 1).

Given the public announcement and private confirmation of the fix, as well as our own testing showing the flaw is no longer apparent, we are now able to publicly report on this case.

Our Prior Investigation

In our April 3 investigation, we discovered that Zoom had “rolled their own” encryption scheme. Our tests showed that voice and video content in a Zoom meeting was encrypted with an AES-128 in ECB mode, using a key shared among all meeting participants. The keys were generated and distributed by Zoom servers, including sometimes Zoom servers in China, where the company has a significant research and development presence. Zoom’s CEO responded that the routing of keys through China happened rarely, and only during periods where a Zoom user experienced a connection failure with Zoom servers in the United States (e.g., due to heavy load).

The Waiting Room Vulnerability

Our April 3 report also referenced (but did not describe) an issue with Zoom’s waiting rooms feature. If a Zoom host enables the waiting room feature for a meeting, then the host must vet potential attendees before they are allowed into the meeting. Prospective attendees in the waiting room see a blank screen with a message: “Please wait, the meeting host will let you in soon” (Figure 1). If the meeting host approves the attendee, then they will be admitted to the meeting.

We discovered that unapproved users in a Zoom waiting room had access to the meeting’s AES-128 key, as well as a live video stream (but not an audio stream) of the meeting. Though this video stream was not displayed in the Zoom UI, an unapproved user could have extracted and decrypted the video from their Internet traffic (Figure 2).

To Disclose or Not to Disclose?

Our logic behind withholding details of the waiting rooms flaw is that it would have been relatively straightforward for a user with moderate technical sophistication to exploit. Anyone who could join a waiting room, extract the AES key from memory (or a packet capture), and understand Zoom’s transport protocol would be able to spy on activities in the meeting while they were waiting for approval to join. While we did not have the opportunity to test Zoom’s HIPAA/PIPEDA-compliant healthcare plan, Zoom’s documentation mentions the use of waiting rooms for telehealth, so we were concerned that disclosure without giving Zoom a chance to address the issue could have immediate negative consequences for user privacy.

In contrast, we judged that other issues we identified with Zoom’s cryptography and key exchange (and publicly disclosed in our April 3 report) were unlikely to be exploited by the average malefactor, and would mainly be applicable to cases of targeted nation-state or industrial espionage. These issues included Zoom’s use of AES-128-ECB encryption to safeguard voice and video content in meetings, as well as Zoom’s occasional use of servers in China to distribute these keys. As we mentioned at the time, these issues should not be concerning for users conducting public or semi-public events on Zoom. We chose to publish these security issues so users who might be concerned with targeted espionage would have the opportunity to take steps to protect themselves while Zoom undertakes the significant effort of implementing the type of end-to-end encryption that would allay these concerns. After our report, Zoom’s CEO committed to implementing end-to-end encryption in its product, though said that this would take several months.

Conclusion: Rebalancing Towards Security

Today, Zoom is under intense scrutiny for security issues reported by a number of researchers, including Citizen Lab. This attention comes just as the company is coping with unprecedented growth and new engineering challenges. We recognize that vendors of video conferencing products need to provide friction-free, low-latency experiences for their users, or risk losing customers. Indeed, the bug that we identified may have its origins in this same pressure: meeting video and decryption keys were provided to waiting room users, perhaps in order to make admittance to the meeting nearly instantaneous.

While good user experience helps users build trust in and goodwill towards a product, security and privacy issues can cause such gains to rapidly diminish. Once trust is lost, the process of rebuilding it can be expensive and time-consuming. In retrospect, investing in security improvements alongside Zoom’s continued growth would have almost certainly been a cost savings.

Trust has never mattered more for online platforms. The reactions around the world to the news of Zoom flaws illustrates how strongly users feel about dependable security and privacy. While it is critical for users to have the information they need to protect themselves, it is also important to avoid overreactions to security weaknesses. As we state in our April 3 report, the issues that we have uncovered thus far should not be concerning to those who use Zoom to keep in touch with friends, hold social events, or organize courses or lectures that they might otherwise hold in a public or semi-public venue.

Fortunately for its users, Zoom’s CEO has committed the company to make significant security and privacy improvements in their app, such as implementing end-to-end encryption. Additionally, Zoom quickly addressed the waiting room issue we identified, and communicated straightforwardly and professionally with us throughout the disclosure process. These steps provide a solid foundation for the company’s new direction. If Zoom continues on this path, their response could serve as a model to other companies facing similar issues.