Key Findings

- Analyzing 100 publicly available sources, we find that since June 2016 China’s police have conducted a mass DNA collection program in the Tibet Autonomous Region. Out of the 100 sources we analyzed, 44 contained figures for the number of DNA samples police had collected in particular areas of Tibet. Based on our analysis of these 44 reports, we estimate that between June 2016 and July 2022, police may have collected between roughly 919,282 and 1,206,962 DNA samples, representing between one quarter (25.1%) and one third (32.9%) of Tibet’s total population (3.66 million).

- Police have targeted men, women, and children for DNA collection outside of any ongoing criminal investigation. In some cases, police have targeted Buddhist monks. Authorities have justified mass DNA collection as a tool to fight crime, find missing people, and ensure social stability. But without checks on police powers, police in Tibet will be free to use a completed mass DNA database for whatever purpose they see fit. Based on our analysis, we believe that this program is a form of social control directed against Tibet’s people, who have long been subject to intense state surveillance and repression.

- We find that mass DNA collection in Tibet is another mass DNA collection campaign conducted under the Xi Jinping administration (2012–present), along with the mass DNA collection campaign in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and the police-led national program of male DNA collection.

Background on DNA Collection in China

In China under the Xi Jinping administration (2012–present), public security work is characterized by two features. The first is intensifying repression and state control, especially in areas with large ethnic and religious minority populations like the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The second is the expansion of invasive state surveillance over the public across China.

Both of these features are evident in the police-led mass DNA collection campaigns which have occurred under the Xi administration. Like police forces around the world, China’s Ministry of Public Security, the national police agency, has operated a forensic DNA database system since the early 2000s. As of 2018, this DNA database system contained 68 million DNA samples. DNA samples in this database are collected as part of criminal or forensic investigations. Using this database, police can compare DNA samples they collect against a larger repository of existing samples in order to determine a suspect’s identity.

But following Xi Jinping’s coming to power, China’s police have begun collecting DNA from entire populations: specifically targeting Uyghurs and other indigenous people in Xinjiang and from tens of millions of men across China.

Mass DNA collection has been an integral part of state repression in Xinjiang. As early as 2016, authorities required local residents to supply DNA samples when applying for travel documents. A region-wide annual “Physicals for All” (全民健康体检) public health program begun in 2016 and which had been visited 53.8 million times by 2019 also reportedly included collecting DNA samples – along with fingerprints and iris and facial scans – from people aged 12–65, according to a 2017 document from Aksu’s prefectural government. DNA collection by the police and other authorities also accompanied the mass detention of perhaps one million people in the region. While the total number of DNA samples collected by authorities in Xinjiang is unknown, it is estimated to be in the millions. (It should be noted that authorities have previously denied that the Physicals for All program included DNA collection.)

Outside Xinjiang, China’s Ministry of Public Security has conducted an even larger program of biometric surveillance. Beginning in 2017, the Ministry of Public Security launched a nationwide program to create a “male ancestry investigation system” (男性家族排查系统) containing DNA samples and genealogical records for 35–70 million Chinese men.

To build this system, local police in communities across China compiled multigenerational family trees for men who shared a common surname and then collected DNA samples from between 5-10% of these men. Because men who share a common surname likely share a common genetic ancestor (and vice versa), police only need a representative sample of male DNA profiles and corresponding family records to match DNA samples from unknown men to a particular family or individual. In the case of China’s male ancestry investigation system, a representative sample may need only be 5-10% of China’s male population, if these samples are combined with extensive family records. While local police have justified this program as a crime prevention measure, none of the men targeted for DNA collection appear to be criminal suspects.

In both Xinjiang and the national male DNA collection campaign, police collected millions of DNA samples without independent oversight from courts, civil society organizations, or the media. Mass DNA collection by China’s police also fits within larger patterns of biometric data collection from the public, including iris scans and voice prints and facial scans.

However, DNA collection is particularly sensitive. In comparison to other biometric markers, DNA samples have the power not only to identify an individual but also the individual’s genetic relatives. DNA samples taken from different people and stored in police-run databases can be compared to determine what kind of genetic relationship exists between these people. Comparisons can be made even without the knowledge or consent of these individuals. This means that the potential coverage of police-run DNA databases extends beyond those individuals from whom the police collected DNA samples, and includes these individuals’ immediate and distant relatives, and any potential offspring. For this reason, the potential surveillance capabilities of the Ministry of Public Security’s DNA databases are uniquely extensive.

Background on DNA Collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Xinjiang and nationwide male DNA collection programs are well-documented. Less clear, however, is whether these are the only mass DNA collection programs police have conducted under the Xi Jinping administration. Evidence from the Tibet Autonomous Region (pop. 3.66 million) – first revealed in a report by Human Rights Watch – indicates that they are not. Our research demonstrates that since June 2016, police in the Tibet Autonomous Region have engaged in a mass DNA collection program targeting men, women, and children across the region. Mass DNA collection appears unconnected to any ongoing criminal investigation. Instead, our research suggests that mass DNA collection is a form of social control directed against the Tibetan people.

Since the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, the Tibetan people have been consistent targets for intense state repression. This repression has included violent crackdowns on dissent in 1987–1989 and 2008, mass surveillance of entire communities, restrictions on religious worship, and the arrest of Tibetans for criticizing state language policies and posting pictures of the Dalai Lama online. State repression against Tibetans has also occurred in areas of Gansu, Sichuan, and Qinghai which historically were part of a larger Tibetan kingdom. However, state repression has been particularly intense and widespread in the Tibet Autonomous Region (hereafter referred to as Tibet).

Under the tenure of Tibet’s Party Secretary Chen Quanguo (2011-2016), authorities implemented new forms of social control, including the grid management and convenience police post neighbourhood surveillance systems. Chen would later bring these programs to Xinjiang during his tenure as that region’s Party Secretary from 2016 to 2021. In Tibet, social control programs were continued under Chen’s successors as Party Secretary, Wu Yingjie (2016–2021) and Wang Junzheng (2021–present). (The United States’ government has sanctioned Chen and Wang for their role in state repression in Xinjiang.)

More broadly, the Xi administration has undertaken major reforms of national ethnic minority and religious policies, with direct consequences for the people of Tibet and other areas of China’s colonial frontier. These reforms have included promoting the “sinicizing” of religions like Tibetan Buddhism and weakening Tibetan language public school education.

Against this background, forensic scientists in China have pursued research that aligns with the party-state’s domestic security concerns. This research has included conducting genetic research focused on people from ethnic minority communities, including Tibetans. In 2017, Human Genetics published an article by police-affiliated researchers on genetic diversity based on nearly 38,000 DNA samples collected from men, including Tibetans and Uyghurs. Concerns about a lack of clear consent from research participants led to the journal retracting the article in 2021. Human rights organizations and others have raised questions about these and other research projects and the role some Chinese researchers have played in state repression of non-Han people.

Until recently, the only known government-led mass DNA collection programs in Tibet were public health-related. Since 2012, public health authorities have conducted annual physical exams for nearly all residents of Tibet, with 3 million receiving medical checks in 2017 alone. Numerous reports indicate that these exams also include the collection of blood samples. A similar program in Xinjiang led to allegations that exams doubled as a form of police surveillance. Despite claims made in earlier reports on police-led mass DNA collection in China, there is no clear indication that Tibet’s annual physical exam program is primarily security-motivated.

Another program of mass DNA collection is the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Human Genetic Resources Sample Database (青藏高原人类遗传资源样本库). Intended to map out human genetic diversity in Tibet and its bordering province Qinghai and improve research into highland diseases and high altitude sickness, the Database was originally proposed in 2017 as part of a broader national initiative by the Ministry of Science and Technology to research biosafety. The program formally began construction in 2018 as a joint project of Qinghai University, Tibet University, Xizang Minzu University, Chinese Academy of Sciences University, and Fudan University. According to a 2018 post on the website of Xizang Minzu University, the completed Database would be made up of two sample banks in Xining in Qinghai and Lhasa in Tibet, a backup sample bank in Xianyang in Shaanxi, and an information database in Xining.

When completed in 2021, the database reportedly contained genetic samples from 100,000 people, including 20,000 samples from a research unit at the People’s Liberation Army’s No. 953 Hospital dedicated to the prevention and treatment of high altitude injury and illness. It is unclear how or from whom these samples were obtained. According to Chinese press reports, the Database is the world’s largest acute high altitude illness specimen bank. Researchers affiliated with the People’s Liberation Army have reportedly become involved with the project. In recent years, Tibet’s border has become a flashpoint in tensions between India and China, and the Chinese military may view the Database as helping to prepare Chinese soldiers for future potential clashes.

The Database could also be a forerunner to the “national surveys of human genetic resources” the Ministry of Science and Technology and provincial-level science and technology departments are meant to organize, according to Article 24 of the draft 2022 Implementation Rules for the Regulations on the Management of Human Genetic Resources. Or it may be part of Chinese government’s efforts to “establish a registration system for genetic resources from important genetic families and people in specified regions” (对重要遗传家系和特定地区人类遗传资源实行申报登记制度), as stipulated in Article 5 of the 2019 Regulations on Human Genetic Resources Management.

The predominantly non-Han people of Tibet and Qinghai would seem to be “important genetic families” from “specified regions.” However, it should be noted that according to Article 2 of the 2019 Provisional Methods on the Declaration and Registration of Human Genetic Resources from Important Genetic Families and People in Specified Regions, “specified regions are not determined on the basis of whether or not they are inhabited by ethnic minorities” (特定地区不以是否为少数民族聚居区为划分依据).

Available reports of Tibet’s physical exam program and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Human Genetic Resources Sample Database indicate that public health authorities and researchers – not police – have led these programs. This does not mean that these DNA samples are beyond the reach of the police. Under Article 16 of the Regulations on Human Genetic Resources Management, government authorities can use any genetic resources collected in China for reasons of public health, national security, and the public interest (为公众健康、国家安全和社会公共利益需要,国家可以依法使用保藏单位保藏的人类遗传资源). However, no publicly available record has been found to indicate that police in Tibet have used the DNA samples contained in the Qinghai-Tibet database or those collected by public health workers.

Through the collection of “basic information” (基础信息) from the region’s residents, however, police in Tibet have also expanded DNA collection beyond criminal or forensic investigations. Police collection of basic information is not unique to Tibet. The creation of a police-run national population basic information system dates back to 2015. According to a 2015 article in the Chinese academic journal Forensic Science and Technology, basic information systems are meant to integrate existing police databases (of people, fingerprints, DNA, etc.) into a single system, to address the problems of incomplete, inaccurate, or duplicated data, and to facilitate data collection and sharing between public security organs across China.

According to this 2015 article, basic information can include personal ID numbers, text messages, banking information, and biometric data like vocal scans and DNA samples. Research suggests that police can in turn use database systems containing this information to surveil Chinese citizens believed to pose a threat to social stability. In practice, collecting, collating, and storing this data presents its own problems. The leak of files on nearly one billion people from a Shanghai police-run database in 2022 highlighted persistent issues with data security and accuracy during a period when the Chinese police are collecting ever greater amounts of data from the public.

In Tibet, basic information collection by police dates back at least to June 2016, as this source from Lhorong County shows. In the prefecture-level city of Chamdo in October 2016, local authorities described basic information collection as strengthening social order and comprehensive governance (加强社会治安综合治理). In some cases, police have conducted a comparable data collection program known as “one proper, three reals” (一标三实), or collecting data on the “proper” address of homes and businesses and the “real” tenants, physical layout, and ownership of local buildings. Like basic information collection, this program has been implemented across China in places like the provinces of Guizhou and Sichuan.

An indication of the scale of basic information collection in Tibet can be found in Chamdo. In 2017 municipal authorities built the Chamdo Public Security Bureau Basic Information Collection System (昌都市公安局基础信息采集系统), which used police, hotels, and retail apps to collect data from all districts, counties, villages, temples, and pasturelands in Chamdo. By May 2019, police had registered 524,500 residents (out of a total population of 798,100) and collected 803,900 pieces of data, in addition to a combined 1.92 million pieces of data collected by hospitality and retail apps.

Basic information collection covering entire cities is not unique to Tibet. What does appear unique to Tibet is that alongside basic information collection, police have also collected DNA samples, often referred to in available reports as “conducting DNA information collection work” (开展DNA信息采集工作). The same 2017 report from Chamdo also refers to “comprehensively building a Chamdo population fingerprint and DNA (blood sample) database” (全面建立昌都市人口指纹和DNA(血样)数据库). Precise details about the scale of this database are not available, though the report does refer to not letting slip a single village, temple, household, or person (坚持“不漏一村一寺、不漏一户一人”目标).

This suggests that police-led DNA data collection in Chamdo could resemble mass DNA collection in Xinjiang or the national program of male DNA collection. Rather than focusing on people implicated in criminal investigations, police in Chamdo appear to have targeted a significant portion of the local population. And as in Xinjiang, mass DNA collection in Chamdo appears to be part of broader state surveillance programs directed against predominantly ethnic minority communities, long the target of widespread state control and repression.

Methodology

To explore the character and scale of police-led mass DNA collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region, we searched online for publicly available reports concerning this campaign. Data collection for this report began December 19, 2020 and ended August 5, 2022.

All sources were publicly available and found online through Chinese language keyword searches on the social media platform WeChat and the search engines Google and Baidu. So as not to jeopardize future research on this topic, we have chosen not to disclose the particular keyword searches we made. However, we did share these search terms with independent peer reviewers of this report prior to publication.

When identifying which sources to collect, we only selected those sources which referred to police DNA collection, DNA database construction, or the importance of DNA collection as a feature of police work in Tibet. To ensure greater trustworthiness, we only collected sources from official government or public security WeChat accounts, government websites, or Chinese domestic news websites. In total, we collected and collated 100 sources.

| Source | Number of Reports |

|---|---|

| WeChat Accounts | 92 |

| Government Websites | 7 |

| News Websites | 1 |

| TOTAL | 100 |

Table 1: Primary Sources by Origin

We also took steps to ensure that sources referred specifically to mass police-led DNA collection, rather than other instances of DNA collection. For example, reports of police collecting DNA from impaired drivers or unhoused people, or of health authorities collecting blood samples as part of health screenings, were not collected or analyzed. Similar DNA collection efforts are either common across China or cannot be definitively linked to police-led mass DNA collection.

We also ensured that all sources referred only to police-led mass DNA collection in Tibet, rather than in areas of historical Tibet in Qinghai or Sichuan where DNA collection has also been reported. Available accounts of mass DNA collection by police in these regions indicate that these are part of the broader national male DNA collection program, not the separate and distinct mass DNA collection program ongoing in Tibet.

Sources were saved as PDFs and archived using Archive Today, then collated in a spreadsheet according to date and location for further analysis. These sources covered the period from June 2016 (the earliest account of mass DNA collection found as part of this report) to July 2022 (the most recent account of mass DNA collection found as part of this report, as of August 5 2022). Of these, 77% were from 2020 to 2022. This may suggest increased data collection efforts beginning in 2020, or simply more open reporting by authorities on this program.

| Year | Number of Reports |

|---|---|

| 2016 | 8 |

| 2017 | 5 |

| 2018 | 8 |

| 2019 | 8 |

| 2020 | 26 |

| 2021 | 29 |

| 2022 (to July) | 16 |

| TOTAL | 100 |

Table 2: Primary Sources by Year

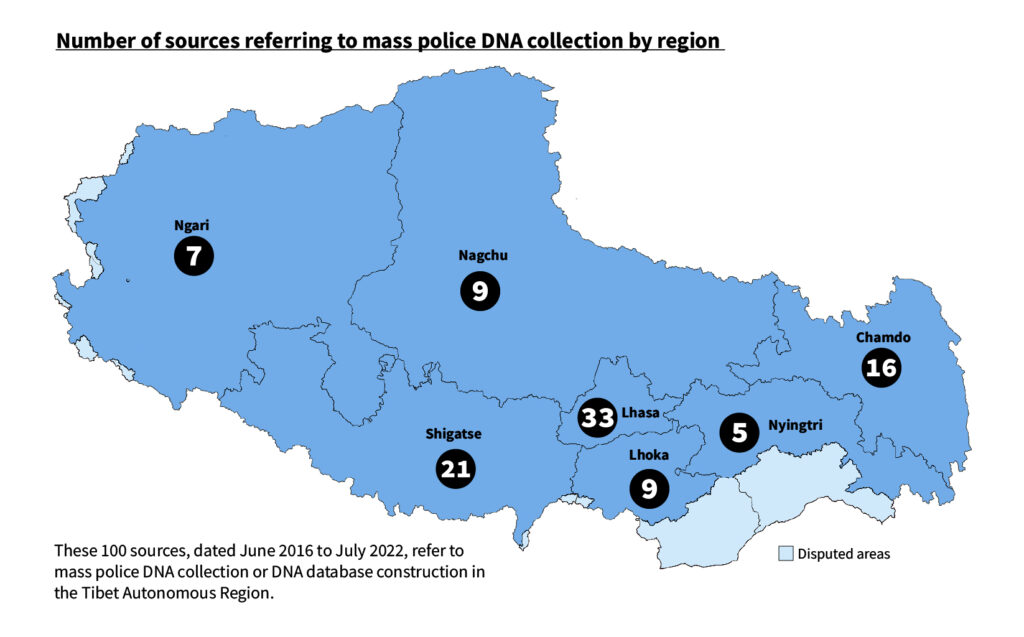

These 100 sources referred to mass police DNA collection or DNA database construction in all of Tibet’s seven administrative regions.

To contextualize mass DNA collection in Tibet between 2016 and 2022, we also drew on other publicly available sources. These sources included government websites which discussed public security programs and police data collection efforts, and Chinese academic literature on police information and DNA database systems.

There are limits to the 100 sources we collected. These sources alone do not provide a fully comprehensive account of police-led mass DNA collection in Tibet. Nor was any single document found which articulates the purpose and scope of mass DNA collection in Tibet between 2016 and 2022. However, by collecting 100 publicly available sources discussing mass DNA collection in Tibet, we were able to create a composite (albeit incomplete) picture of this program.

Findings

The 100 sources we collected provide insight into the scope of mass DNA collection in Tibet. These sources suggest that mass DNA collection is unconnected to ongoing criminal investigations. Instead, our analysis indicates that for years police across Tibet have collected DNA samples from men, women, and children, none of whom appear to be criminal suspects. Nor do these sources state that police are collecting DNA only from particular groups of Tibetans, like activists or political critics. Instead, these sources indicate that police are targeting entire communities in Tibet for DNA collection, often as part of broader information collection and surveillance programs.

Police-led mass DNA collection in Tibet dates back as early as June 2016, during the last months of Chen Quanguo’s tenure as Tibet’s Party Secretary. Out of the 100 sources we examined, three were from between June and July 2016, prior to Wu Yingjie succeeding Chen as Party Secretary in August 2016. While the mass DNA collection program has been a feature of both Wu Yingjie and Wang Junzheng’s respective tenures as Party Secretary, preliminary groundwork was laid under the Chen Quanguo administration.

The earliest mention we found of mass DNA collection comes from Chamdo. We found eight sources, published between June 2016 and February 2017, which discussed mass DNA collection in two counties of Chamdo, Lhorong and Dragyab. By the end of this period, authorities in Dragyab had reportedly collected 25,055 DNA samples from the county’s population of 50,294.

Chamdo appears to have been a testing ground for a later Tibet-wide program of mass DNA collection. The earliest instance of DNA collection outside Chamdo we examined occurred in April 2017 in the capital Lhasa and was led by police officers from Dragyab. This suggests that, like the male DNA collection program which began in Henan Province in 2014–2016 before expanding nationwide in 2017, DNA collection in Tibet was tested out in one area before spreading across the region. By August 2017, the then-Deputy Public Security Bureau Chief of Lhasa was noting the importance of DNA data collection to stability and public security work.

In Lhasa and beyond, police often collected DNA while conducting other work, including warning the public against the risk of telephone and online fraud or implementing pandemic control measures. In other cases, DNA collection was part of the “1 million police entering 10 million homes” (百万警进千万家) campaign, a national program of police-led home and business inspections and data collection.

Training sessions, like those held by the Public Security Bureau of Shigatse Prefecture in September and October 2019, emphasized the importance of DNA collection as a feature of police work. As with the collection of other forms of basic information, data accuracy was paramount. In Nyima County in June 2019, police officers were held personally responsible for ensuring the accuracy of all data they collected. Participation in blood or DNA collection work has even been cited in commendations for three police officers in Churshur County, with one report referring to the collection of DNA from “everyone” (全民DNA血样采集).

Specific groups have also been targeted. Police have collected DNA samples from Buddhist monks. Monks are important pillars of Tibetan society and have participated in protests against the Chinese government and state policy, including through self-immolation. In response, authorities have sought to discipline Tibet’s monastic community through surveillance, arrests, and prosecutions. It is not therefore not surprising that police have also targeted monks for DNA collection. In Chamdo, data collection reportedly included the region’s 78 temples and religious sites.

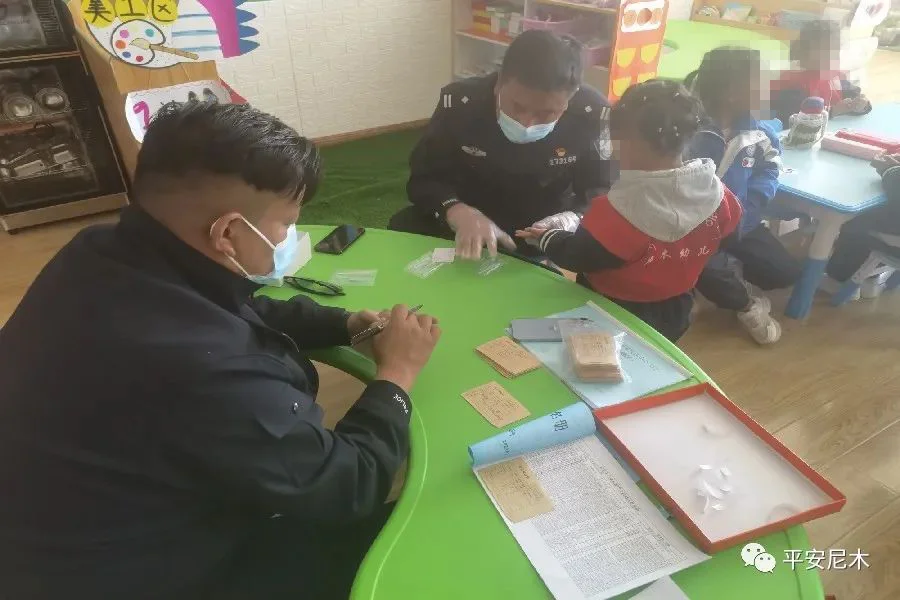

As in the male DNA collection campaign, the police have also collected DNA samples from children. In one instance in Nyemo County in April 2022, police enlisted the support of teachers in order to collect DNA samples from elementary school students.

While mass DNA collection is a police program, some reports refer to or show photographs of medical personnel collecting DNA samples under police supervision. This lends credence to earlier accounts from Xinjiang about public health workers gathering biometric data for the police.

Source: “Dagze County Public Security Bureau Makes Sold Progress in DNA Data Collection Work, Completes DNA Database,” Dagze Public Security Police Bulletin, October 11, 2017, WeChat

However, while the annual physical exams in Tibet also involve mass blood collection, there is no indication that blood collection by police in Tibet is connected to this public health program, despite earlier speculation to the contrary. As part of the mass DNA collection campaign, samples are taken via a pinprick to the forefinger and with a specially treated paper swab, a method resembling that used in the national male DNA collection campaign. In contrast, health workers typically take larger samples via intravenous injections and plastic vials.

Source: “Lhaze County Public Security Bureau Record of Recent ‘Service’, ‘Management’,” Lhaze Police, March 31, 2020, WeChat

Source: “Police Work Dynamics, Nyainrong County Public Security Bureau Continues DNA Blood Sample Information Collection Work,” Nyainrong Online Police, October 13, 2021, WeChat

When police finish collecting DNA and other basic information, this information is uploaded to computers and reported to their superiors, as occurred in Sa’gya County in January 2022. Based on what is already known about the Ministry of Public Security’s forensic DNA and male DNA databases, as well as references in these reports to the building of “local population gene databases” (辖区人口基因数据库), Tibet’s Public Security Bureau may be creating a system of interlinked local DNA databases which together will cover all of Tibet’s administrative regions. These databases in turn will likely be connected to other police-run databases, including those containing personal files for perceived threats to social stability.

None of the sources we examined referred to police collecting DNA samples from people suspected of a particular criminal offense. Nor were any of the areas in which police collected DNA samples – including fields, monasteries, residential neighbourhoods, homes, schools, businesses, and construction sites – described as crime scenes.

Instead, police across Tibet have broadly targeted men, women, and children. In some instances, police have focused DNA collection on particular groups, including people obtaining license plates for e-bikes, migrant workers, migrants, and herders. In two instances, reports referred to police specifically targeting men for DNA collection. But in general, the focus of DNA collection seems to be on all local residents.

Source: “Lhoka Police Bulletin,” Lhoka Public Security, August 31, 2021, WeChat

Source: “Qiangtang Defender, Golden Shield Vanguard, Gerze County Public Security Bureau Mami Village Police Station Deepens the Implementation of District DNA Blood Sample Information Collection Work,” November 26, 2021, WeChat

It is not clear if anyone has refused police requests for DNA samples, nor how or if authorities have punished people who have refused. China’s police possess a wide array of legal and extra-legal powers and it is likely that they have used these powers to demand compliance with requests for DNA samples. Anecdotal reports from the male DNA collection campaign suggest that those who refuse police requests could be denied the right to travel or have their residency permit revoked.

Source: “Nyemo County Public Security Bureau Focuses on Implementing DNA Sample Collection Work,” Safe Lhasa, April 22, 2022, WeChat

Chinese Government Justifications for DNA Collection

Across Tibet, police have engaged in mass DNA collection, targeting men, women, and children. Despite – or because of – the scale of this campaign, police appear to be sensitive to public reactions. For years, police in Tibet have attempted to gain public support for DNA collection. As early as April 2017 in Lhasa, police were reportedly informing the public about when and where data collection would take place, and calling on residents to cooperate.

Confusion and concern about DNA collection seem widespread. In June 2020 in Nagartse County, police attempted to prevent negative views about DNA collection from spreading, while in Shigatse in October 2020 authorities sought to downplay the worries of migrant workers from whom they were collecting DNA samples. And in Gangdu in October 2020 police were said to have “proactively dispelled the confusions and doubts of those from whom data were collected” (积极消除被采集群众的困惑和疑虑). Outside Tibet, police have also had to deal with public concerns about the mass DNA collection. The root of these concerns may be the same: confusion about what purpose police-led mass DNA collection serves.

The purpose of DNA data collection are reportedly spelled out in documents released by Public Security Bureaus across Tibet, like the “Churshur County Public Security Bureau Notice on Further DNA Data Collection Work” (曲水县公安局关于下一步DNA数据采集工作的通知). Such documents are not publicly available. Instead, to gain insight into how police across Tibet have justified mass DNA collection, we analyzed descriptions of DNA collection provided in these 100 sources.

Authorities have provided multiple justification for mass DNA collection. The most commonly cited are related to public security, including fighting crime (打击违法犯罪活动) or violent terrorism (暴力恐怖), making use of DNA in criminal investigations (发挥DNA血液样本在案件侦破), improving public security prevention and control work (提高公安机关社会治安防控水平), and maintaining social stability (维护社会稳定). Yet given that domestic security work in China includes both controlling crime and controlling Chinese society, the line dividing fighting crime and political repression is often blurred.

Other security-related justifications seem more overtly political. A reference in one 2021 source to safeguarding the gains of dedicated struggles (保障专项斗争成果) could refer to a politically-motivated national “sweep the black” (扫黑除恶) anti-crime campaigns which began in 2018 and which authorities in Tibet have used to suppress critics and religious practitioners.

Police have also claimed that DNA collection will assist with population management (人口管理), a term which covers a range of activities from administering the household registration system to monitoring perceived threats to social stability. Other sources refer to the role of DNA collection in upgrading national ID cards (身份证改代升级). (Police also referred to upgrading national ID cards during the male DNA collection campaign.)

In other cases, police have said DNA collection will help combat human trafficking and find lost people (“打拐”、查询失踪人口) or “protect the masses” (保护人民群众). These explanations suggest that mass DNA collection is meant to supplement existing police-run DNA databases, like the National Anti-Trafficking DNA Database, which as of 2016 contained 513,000 DNA samples. Yet outside Tibet, police collection of DNA for the purpose of recovering missing or trafficked children is generally restricted to family members, rather than entire local populations.

Estimating the scale of data collection

Our analysis indicates police have collected DNA samples in locations across Tibet. However, it is unknown precisely how many DNA samples police have already collected. An October 2020 source from Lhoka Prefecture (pop. 354,000) refers to the building a local population gene database (辖区人口基因数据库), though how much of the local population this database would cover is left undefined.

Researchers have produced credible estimates for the scale of DNA collection elsewhere in China. In Xinjiang, authorities reportedly collected DNA samples from entire local populations of Uyghur and other indigenous people aged 12 to 65. In the national male DNA collection campaign, the Ministry of Public Security aimed to create a male ancestry investigation system containing DNA samples from between 5-10% of China’s male citizens. If the mass DNA collection program in Tibet resembles these two programs, then police across Tibet are also likely aiming to meet data collection quotas set by their superiors.

What quotas authorities have set for DNA sample collection is unknown. As previously discussed, we know that police have targeted both men and women. We also know that police have targeted the elderly and elementary school students. However, none of the 100 sources we collected specify an age range for those police to target.

Even collecting DNA samples from a subset of a region’s population can require years of police work. A male DNA collection campaign in Henan Province, predating the national male DNA collection campaign, took place over two years from 2014–2016. The completed database contained 5.3 million DNA samples, representing roughly 5% of Henan’s population of 107 million people in 2016. The decision to collect DNA samples from only a subset of local populations in places like Henan may reflect wider problems facing China’s police. While China’s Ministry of Public Security enjoys considerable authority, research suggests that local police capacity is limited by resource constraints, the demands of superiors, and overwork. Limited policing capacity may partially explain why Tibet’s ongoing mass DNA collection has taken years to complete, and why police may not intend to collect DNA samples from Tibet’s entire population.

The nature of DNA data also suggests that police may not need to collect samples from every resident in order to achieve comprehensive genetic coverage of Tibet’s population. DNA samples taken from different individuals can be compared to determine if a genetic relationship between the two people exists. For example, China’s “male ancestry investigation system” may contain DNA samples from 35-70 million men, 5-10% of China’s male population. When combined with the system’s multigenerational family trees for each of these men, however, this system could give police genetic coverage of China’s total male population of roughly 700 million.

As previously discussed, police in Tibet also appear to be combining DNA with other population data known as basic information or the “one proper, three reals.” By collecting basic information or the “one proper, three reals” from the region’s residents, and DNA samples from a subset of these people, police could have enough information to connect nearly any DNA sample from an unknown person back to a known person or their genetic kin. We therefore believe that police have not collected DNA samples from everyone in Tibet, nor do police need to in order to achieve extensive genetic coverage of Tibet’s total population.

When estimating the scale of police-led DNA collection in Tibet, we were also careful not to overestimate. Previous research on the male DNA collection campaign suggests that police in some areas of China collected far more data than their peers elsewhere, despite potentially working towards similar data collection targets. Such discrepancies are also evident in Tibet. Higher totals in places like Dragyab County may reflect overzealous collection by local public security officers. Or higher totals in some areas could be an attempt by police to offset lower collection rates elsewhere. Therefore, we must be mindful to not mistake the scale of DNA collection in a specific region of Tibet as being representative of the scale of DNA collection in Tibet at large.

Police collection of DNA may vary for other reasons. It is possible that an area’s ethnic composition informs the police’s calculations on how many DNA samples to collect. Police may collect more samples in heavily Tibetan areas like Dragyab, where less than 1% of the population are ethnic Han, compared with areas with a higher proportion of ethnic Han residents. Multiple reports from Xinjiang suggest that authorities there were particularly concerned with collecting DNA samples from Uyghur and other indigenous peoples. It is possible that police in Tibet are also particularly interested in collecting DNA samples from the region’s indigenous non-Han majority.

Demographic data from 2021 indicates that Tibet’s population is made up of roughly 3.13 million ethnic Tibetans, 66,000 people of other ethnicities, and 443,000 ethnic Han. Tibet’s ethnic Han residents are spread out across all of Tibet’s seven administrative regions. However, certain administrative regions have proportionally larger ethnic Han populations than others. Lhasa (pop. 867,891) has 233,082 ethnic Han residents, representing roughly 26.8% of the local population, while Nyingtri (pop. 238,936) has 58,983 ethnic Han residents, representing roughly 24.6% of the local population. These two administrative regions are home to roughly 66% of Tibet’s total ethnic Han population. We therefore assume that these areas are outliers when it comes to the proportion of the local population police have targeted for DNA sample collection.

In order to estimate the current scale of DNA collection in Tibet, we examined the 100 sources listed in Table 2. Out of these 100 sources, only 44 provided specific figures for the number of DNA samples police collected. These figures are as low as 15 DNA samples to as many as 40,200. Among these 44 sources, many state that DNA collection efforts were ongoing at the time of the sources publication, suggesting that police in these areas have continued to collect more DNA samples.

Out of these 44 sources, reports from three regions – Lhorong County and Dragyab County in Chamdo, and Churshur County in Lhasa – provide good insight into the scale of DNA collection in Tibet. Analysis of these reports either suggest that DNA collection in these three regions has ended, or provide clear estimates for the total number of DNA samples collected within that specific region.

In Lhorong County between June and October 2016, police collected basic information – including DNA samples – from local residents. Ten reports from this period provide figures on how many DNA samples police collected in six villages and three townships in Lhorong, along with one report which does not specify a particular location. Together, these six villages and three townships have a combined estimated population of 41,689. By comparing these figures with the combined estimated population of these six villages and three townships, it is possible to estimate the proportion of the public from whom police collected DNA samples. Based on these reports, by October 2016 police in Lhorong had collected DNA samples from at least 17,335 people, or 41.2% of the combined population of these areas.

| Location | # of DNA Samples Collected | Local Population | DNA Samples as % of Local Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lhorong County

(no area specified) |

758 | – | – |

| Atoka Village | 281 | 1,500 (est.) | 18.7% |

| Yuxi Village | 573 | 1,350 | 42.4% |

| Lajiu Village | 3,500 | 6,005 | 58.2% |

| Zhongyi Village | 1,506 | 3,544 | 42.4% |

| Xinrong Township | 1,560 | 4,304 | 36.2% |

| Dalong Village | 502 | 6,225 | 9.1% |

| Xobando Township | 2,839 | 5,516 | 51.4% |

| Exi Village | 2,410 | 7,020 | 38.7% |

| Kangsha Township | 3,265 | 6,225 | 52.4% |

| TOTAL | 17,194 | 41,689 | 41.2% |

Table 3: DNA Collection in Lhorong County from June to October 2016.

In order to determine the proportion of people across Lhorong County from whom police collected DNA samples, we can compare the number of DNA samples collected (17,194) to the total population of Lhorong (53,185). Doing so gives us a new estimate that police collected DNA samples from 32.3% of Lhorong’s total population. Out of the 100 sources analyzed, we found no sources referring to DNA collection in Lhorong published later than October 2016. We therefore assume that DNA collection was largely completed by this date.

In Dragyab County (pop. 57,065) in Chamdo, a February 2017 report states that police had collected 25,055 DNA samples. According to our calculations, 25,055 DNA samples cover approximately 43.9% of the total local population. Out of the 100 sources analyzed, we found three sources referring to DNA collection in Dragyab published later than February 2017: on January 12, 18, and 29, 2018, respectively. These reports, which show that in total police collected a further 7,952 DNA samples, seem to be related to a program to relocate people living in high-altitude areas and urbanize rural residents. It is possible that DNA collection continued beyond February 2017 as part of a specific state-backed program of population resettlement.

In Lhasa’s Churshur County, a January 2021 source states that police collected 40,200 DNA samples. This source also states that these 40,200 DNA samples covered 75% of the county’s permanent and temporary population. This implies that Churshur’s population of permanent and temporary residents is roughly 53,600, higher than the official total of 41,851, which may not take into account temporary residents. (Two other sources also from January 2021 provide similar estimates for the number of DNA samples police collected.) This source also claims that the DNA samples collected in Churshur represented 42.5% of the total number of DNA samples contained in Lhasa’s municipal DNA database. This suggests that the remainder of Lhasa’s DNA database contained DNA samples from roughly 54,388 people. In total, this suggests that as of January 2021 police in Lhasa had collected DNA samples from roughly 94,588 people

We then estimated the proportion of Lhasa’s population these 94,588 samples represented. However, because police reportedly collected DNA from both permanent and temporary residents in Churshur, we chose to make our estimates based on a revised figure for Lhasa’s total population. Rather than using the figure of 867,891, which only includes permanent residents of Lhasa, we used another official figure of 950,000, which appears to take into account both permanent and temporary residents. Based on this revised population figure, we estimate that the 94,588 DNA samples collected by police in Lhasa represent 9.9% of the city’s total population of permanent and temporary residents.

Out of the 100 sources analyzed, we found 17 sources referring to DNA collection in Lhasa published later than January 2021. These include a January 2022 report from Lhünzhub Township referring to the collection of 2,000 DNA samples, a June 2022 report from Gyaidar Township referring to the collection of 218 DNA samples, and a June 2022 report from Churshur County referring to the collection of 1,438 DNA samples. We therefore assume that DNA collection continued in Lhasa beyond January 2021.

We treated the estimated proportion of local residents police targeted for DNA collection in Lhorong County (32.3%), Dragyab County (43.9%), and Lhasa (9.9%) as clues concerning the scale of DNA collection across the entirety of Tibet.

| Location | DNA Samples Collected | Local Population | DNA Samples as % of Local Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lhorong County | 17,194 | 53,185 | 32.3% |

| Dragyab County | 25,055 | 57,065 | 43.9% |

| Lhasa | 94,588 | 950,000 | 9.9% |

Table 4: DNA Collection Totals from Four Key Regions in Tibet.

In addition, we also estimated the proportion of local residents police targeted in Nyingtri. As previously stated, we believe that police DNA collection in Nyingtri may resemble police collection of DNA in Lhasa, due to Nyingtri’s similarly high proportion of ethnic Han residents. Assuming that police in Nyingtri also collected DNA samples from roughly 9.9% of the local population, we estimate that the total number of DNA samples police collected in Nyingtri equals 23,654.

To estimate the total number of people in Tibet police have collected DNA samples from as of July 2022, we first separated Tibet into those areas a comparatively high proportion of ethnic Han residents (Lhasa and Nyingtri) and those regions with a comparatively lower proportion of ethnic Han residents (the remainder of Tibet). We then subtracted the combined population of Lhasa and Nyingtri (1.18 million) from the population of Tibet (3.66 million) to determine the population of those regions with proportionally fewer ethnic Han residents, roughly 2.48 million.

We then estimated the total number of DNA samples police may have collected outside Lhasa and Nyingtri. Estimate One was based on the proportion of people police collected DNA samples from in Lhorong (32.3%). This gave us an estimate of 801,040 DNA samples collected in Tibet, excluding Lhasa and Nyingtri. Estimate Two was based on the proportion of people police collected DNA samples from in Dragyab (43.9%). This gave us an estimate of 1,088,720 DNA samples collected outside Lhasa and Nyingtri.

We estimate that the combined number of DNA samples police collected in Lhasa and Nyingtri is 118,242. We then added the estimated total number of DNA samples collected in Lhasa and Nyingtri to our two estimates for the rest of Tibet. When added to Estimate One (801,040), this gave us a combined estimated total of 919,282 DNA samples for the entirety of Tibet, representing a quarter (25.1%) of Tibet’s total population. When added to Estimate Two (1,088,720), this gave us a combined estimated total of 1,206,962 DNA samples, equal to a third (32.9%) of Tibet’s total population.

| Estimated DNA Samples Collected Outside Lhasa & Nyingtri |

Estimated DNA Samples Collected in Lhasa & Nyingtri |

Estimated Total Number of DNA Samples Collected in Tibet | Total Number of DNA Samples as % of Tibet’s Total Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate One | 801,040 | 118,242 | 919,282 | 25.1% |

| Estimate Two | 1,088,720 | 118,242 | 1,206,962 | 32.9% |

Table 5: Estimated Total Number of DNA Samples Collected in Tibet.

Increasing our confidence in this estimate are data found in a 2020 thesis entitled “Efficiency Evaluation and Strategy Research of National DNA Database Construction” (国家DNA数据库建设的效能评估及策略研究) written by a member of Anhui Province’s Public Security Bureau for Harbin Institute of Technology’s graduate program in public administration. This thesis includes an extensive appendix detailing the size of provincial-level police-run DNA databases across China, as well as provincial-level anti-trafficking DNA databases and male ancestry investigation systems. It is not possible to independently verify these figures. Nor does the author provide a source for this data. However, the author’s affiliation with both Anhui’s Public Security Bureau and the Harbin Institute of Technology lends credibility to these figures.

Table 1 in this graduate thesis provides figures for “national DNA database construction” (全国DNA数据库建设) in each of China’s major administrative areas (including the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps but excluding Hong Kong and Macau) between January and June 2020. These figures are broken into three columns: “total number [of] newly added [DNA samples] to the database” (新增入库分型总数), “total number [of DNA samples] in the database” (数据库分型总数), and “A1.” Data in the first two columns are numbers, while data in the third column are percentages. The final column “A1” represents the number of newly added DNA samples (column one) as a proportion of the total number of DNA samples in the database (column two).

For Tibet, the number of newly added DNA samples in the first column is 134,306; the total number of DNA samples in the second column is 631,460; and the percentage in the final column “A1” is 21.27%. These figures suggest that by mid-2020, police in Tibet had collected DNA samples from 631,460 people, or roughly 17.2% of Tibet’s total population. They also indicate that in a six month period (January to June 2020), police collected DNA samples from 134,306 people, or roughly 3.6% of Tibet’s total population.

We can compare these figures to our own estimate of DNA collection in Tibet. Based on Estimate One that police have thus far collected 919,282 DNA samples, this suggests that between June 2020 to July 2022 police could have collected a further 287,822 DNA samples. The DNA samples collected during this two year period alone would account for roughly 7.8% of Tibet’s total population. Based on Estimate Two (1,206,962), this suggests that between June 2020 and July 2022 police may have collected another 575,502 DNA samples, accounting for roughly 15.7% of Tibet’s total population.

If we are correct in concluding that police have collected DNA samples from roughly one quarter of Tibet’s population, the mass DNA collection campaign in Tibet could be the largest such campaign (relative to population) conducted anywhere in China, with the possible exception of Xinjiang.

Discussion

For decades, China’s Ministry of Public Security has engaged in domestic intelligence gathering. Police have collected information on the Chinese public through citizen informants, the grid management system, phone trackers, and a national video surveillance network. Under Xi Jinping, police intelligence gathering has not only continued but grown to include the mass collection of DNA samples. National authorities have not publicly commented on mass DNA collection in Tibet. We are therefore left to speculate on the scope and character of the program.

Based on our analysis of the 100 sources we collected, we believe that mass DNA collection in Tibet is part of the Ministry of Public Security’s broader efforts to collect population data from Chinese citizens for the purpose of social control. Mass DNA collection from ethnic and religious minority communities outside criminal investigations is unique to the Xi administration. And in Tibet, mass DNA collection has deepened state control over indigenous people the Chinese government has long worried are insufficiently loyal to the party-state.

Mass DNA collection in Tibet also highlights enduring features of policing in China. China’s domestic security apparatus is responsible for both controlling crime and controlling Chinese society. China’s police are expected to be politically loyal to the Communist Party. What’s more, political repression against ethnic and religious minorities like the people of Tibet, as well as civil society activists and political critics, is often justified in terms of fighting crime. Authorities have used anti-crime campaigns in Xinjiang to crack down on Uyghurs and other indigenous people. Elsewhere in China, authorities have used the courts to charge feminist activists, labour activists, and human rights lawyers with “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” “disturbing public order,” and “subversion of state power.”

The conflation of crime control and social control is also evident in the mass DNA collection campaign in Tibet. Without independent courts, a free press, independent civil society, or opposition political parties, police in Tibet are free to collect DNA samples from whomever they wish and for whatever purpose they want. A completed population-wide DNA database system could be used during forensic investigations or to help reunite missing people with their blood relatives, as some government reports claim. But DNA data stored in a population database could also be used to justify the arrest, prosecution, and detention of government critics, civil society activists, monks, and ordinary people. And by deepening state surveillance over the people of Tibet, it could bring Tibet’s people under even tighter state control.

Nonetheless, there is a tension between mass DNA collection and Chinese law. Article 132 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law states that police may only collect blood samples from victims or suspects in criminal proceedings. Those targeted by police in Tibet for this program of mass DNA collection appear to be neither. In the past, China’s police have also publicly expressed reluctance to collect DNA samples from China’s entire population. In 2015, the Ministry of Public Security responded to a public suggestion that authorities collect DNA during the household and national ID card registration processes by stating that DNA collection touched upon social questions like ethics and personal privacy, and that current conditions did not allow for the collecting of DNA for these purposes. Similar calls by members of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in 2017 and 2022 to build national DNA databases to fight human trafficking and child abduction have not elicted extensive public comment by the Ministry of Public Security.

Chinese researchers affiliated with the police have also warned about the dangers of mass DNA collection. A 2015 article in Forensic Science and Technology written by a researcher for the Ministry of Public Security’s Forensic Science Division cautioned that collecting DNA outside the scope of the Criminal Procedure Law could become a factor contributing to social instability, while a 2018 article in the Journal of Hubei Police Academy warned that the mass blood collection could violate Chinese law and international norms.

In the rare instances when police have both publicly acknowledged mass DNA collection and linked it to a specific criminal investigation, there has been pushback. The decision of police in Shandong in 2013 to collect DNA samples from 3,600 students in response to a series of campus thefts led to criticism by Chinese legal experts, who questioned how thousands of students could all be suspects in a single case.

Concerns like these have not been enough to halt mass DNA collection in Tibet. Nor are they likely to halt further instances of police-led mass DNA collection, in Tibet or elsewhere in China. The Chinese government has introduced legislation covering personal privacy and genetic data, something many Chinese legal scholars have championed for years. However, the 2019 Regulations on Human Genetic Resources Management, the 2021 Personal Information Protection Law, and the 2022 draft Detailed Rules for the Implementation of the Regulations on the Management of Human Genetic Resources do not limit the power of the police to collect personal information and DNA data from Chinese citizens. Nor is it likely that these documents will limit future instances of police-led mass DNA collection in Tibet.

Our research indicates that mass DNA collection in Tibet began in particular areas of Tibet in 2016, before expanding to the rest of the region in subsequent years. The gradual expansion of this campaign is in keeping with known Chinese government practices. For decades, the Chinese government has allowed local authorities to experiment with new policies before expanding successful experiments nationwide, including in the area of surveillance. China’s male DNA data collection program was first implemented in Henan Province in 2014 before expanding nationally in 2017. Similarly, under the tenure of Tibet’s former party secretary Chen Quanguo, surveillance programs like convenience police stations were implemented in Tibet before being extended to Xinjiang. While police-led mass DNA collection has so far been limited to Tibet, Xinjiang, and a subset of China’s male population, it is possible that the Ministry of Public Security will launch similar programs in the future. It is also possible that mass DNA collection from men, women, and children may expand to target ethnic Tibetan communities in regions outside the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Police-led programs of mass DNA collection are a particular feature of the Xi Jinping administration. However, the implications of police DNA collection for human rights and privacy extend beyond China and are an issue for countries around the world. Without clear limits on police DNA collection, the possibility for misuse is great. States – including China – must enact and enforce strict limits on police collection, analysis, and storage of DNA and other sensitive biometric data, in order to minimize the potential harm to those from whom data were collected, their kin, and their wider community. And at the international level, states, civil society groups, researchers, and international organizations should work together to establish global norms on the proper handling of biometric data.

Acknowledgements

Research for this project was supervised by Professor Ron Deibert.

We would like to thank Ausma Bernotaite, Donald Clarke, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Ron Deibert, Victor Falkenheim, William Goodwin, Daria Impiombato, Jeff Knockel, Yves Moreau, Vicky Xu and Mari Zhou for valuable feedback.

Sources

Primary sources collected for this project are available here.