Not Safe for Politics

Cellebrite Used on Kenyan Activist and Politician Boniface Mwangi

Illustration by DD

Following the widely-condemned arrest in July 2025 of prominent Kenyan opposition voice Boniface Mwangi, the Citizen Lab analyzed artefacts from devices seized during the arrest. We found that Cellebrite’s forensic extraction tools were used on his Samsung phone while it was in police custody. This case adds to the concerning pattern of the misuse of Cellebrite technology by government clients.

Widely-Condemned July 2025 Arrest and Device Seizure

Boniface Mwangi is a prominent dissenting voice, activist, and politician in Kenya who has announced his intention to run for president in Kenya’s 2027 elections.

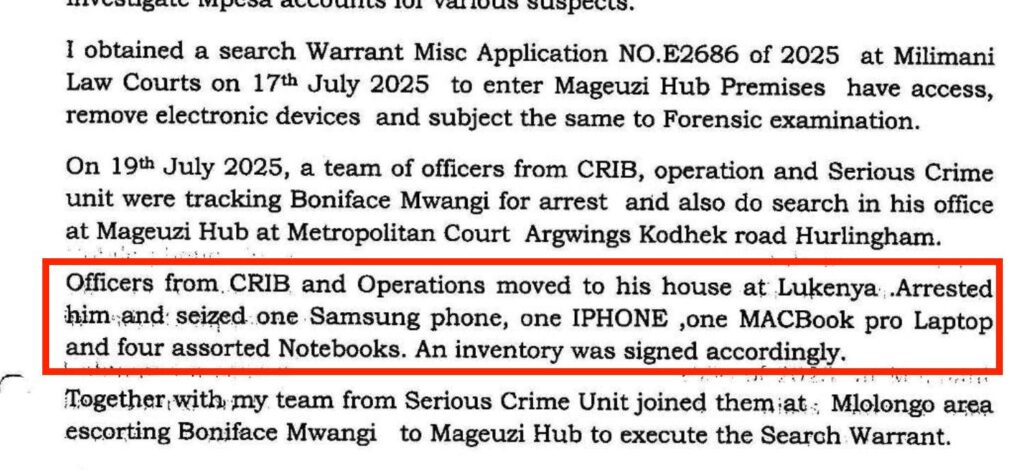

On July 19, 2025, Mwangi was arrested at his home by officers of the Kenyan Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI), which is part of the Kenyan National Police Service. He was subsequently taken by the authorities to his office, a co-working and activist space in Nairobi. DCI officers raided both Mwangi’s home and office, seizing several of his devices.

The arrest occurred in the context of widespread 2025 protests against extrajudicial killings by the Kenyan authorities, and came a year after mass protests triggered by a controversial 2024 finance bill. During those protests, at least 60 people were killed and many more injured, and hundreds more were arbitrarily detained or forcibly disappeared.

Two days later, Mwangi was brought before a special court that deals with terrorism and transnational crime and was charged with various offences under a firearms law. The authorities had initially claimed they would charge Mwangi under terrorism and money laundering laws related to his role in the June 25, 2025 anti-government protests where 19 demonstrators were killed in clashes with Kenyan police. Mwangi denied the terrorist accusations and the charges were strongly condemned by human rights groups as part of a “systematic crackdown” against protestors.

Authorities later reportedly dropped the terror-related charges in the face of widespread international condemnation. Following his initial court appearance, Mwangi was released on bail. His criminal case remains active at the time of writing. Mwangi has been repeatedly subjected to human rights abuses. For example, in May 2025, Mwangi was in Tanzania in order to monitor the trial of a political opposition leader, Tundu Lissu. In what appears to have been an act of transnational repression by the Kenyan authorities and facilitated by Tanzania, he was arbitrarily detained, arrested, forcibly disappeared, and brutally tortured by the Tanzanian authorities. Around the same time, during the launch of Tanzania’s new foreign policy, the President of Tanzania stated that “foreign activists from neighboring countries should not be allowed in Tanzania because they disrupt peace.”

Prior to this case, Mwangi has a history of being subjected to arbitrary detentions and arrests for his outspoken activism.

Confirming the Use of Cellebrite on Boniface Mwangi’s Phone

The Kenyan authorities returned the devices seized during the July 19, 2025 raid to Mwangi on September 4, 2025. Mwangi immediately observed that the Samsung phone had its password protection removed and could now be opened without a password. He states that he never provided the device’s password to the authorities.

Researchers at the Citizen Lab analyzed artefacts collected from Mwangi’s devices shortly after they were returned to Mwangi and performed an analysis for evidence of compromise.

Our analysis of the Samsung Android phone confiscated by the Kenyan police belonging to Mwangi shows signs that Cellebrite was used on the phone on or around July 20, 2025 and July 21, 2025. The device was in the custody of the Kenyan police during this timeframe.

We observed traces of an application named com.client.appA on the Android phone. The Citizen Lab associates this application name with high confidence with Cellebrite’s forensic extraction technology. Other sources have also linked this indicator with Cellebrite’s forensic extraction technology.

The use of Cellebrite could have enabled the full extraction of all materials from Mwangi’s device, including messages, private materials, personal files, financial information, passwords, and other sensitive information.

Our analysis on artefacts from this and other devices seized in this case is ongoing.

Cellebrite in Kenya: More Human Rights Abuses

The findings detailed in this research note add to the growing body of evidence that Cellebrite’s technology is being abused by its government clients, and the company is failing to prevent those abuses from happening.

Kenya’s Use of Cellebrite: A Cause for Concern in Light of Kenya’s Extensive Human Rights Violations

International human rights law limits a state’s interference with fundamental rights and freedoms. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),1 for example, protects the right to privacy, freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and the right not to be subjected to arbitrary arrest and detention. Any measures by a state aimed at limiting these rights must be necessary and proportionate and must not be used in a retaliatory manner.2

Mwangi’s arbitrary arrest and the use of Cellebrite’s forensic technology in the context of this arrest and without consent likely violates both regional and international human rights law and the Kenyan constitution, which protects fundamental rights and freedoms, including the right to privacy, freedom of expression, freedom of association, assembly, demonstration, picketing, and petition. The actions of the Kenyan government against Mwangi have been widely criticized by human rights organizations.

The Kenyan government’s decision to drop charges of terrorism and money laundering for lesser charges only after widespread publicity and international condemnation is suggestive of politically motivated targeting due to Mwangi’s position as a high-profile political opposition figure, and possibly as a retaliation for his organization of and participation in protests and his political activities.

A government’s use of technology to extract data from the phones of persons subjected to arbitrary arrests and unlawful criminal prosecutions or in response to their lawful exercise of their fundamental rights such as the right to freedom of expression or the right of peaceful assembly cannot meet the requirements of international human rights law and thus cannot be justified.

The Kenyan government’s use of Cellebrite technology against Mwangi is part of a broader ecosystem of surveillance abuses by the Kenyan authorities that have been broadly documented by human rights organizations. In July 2025, the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law published a detailed report describing the state’s widespread abuse of surveillance technologies, underscoring the “adverse effects of unlawful surveillance on civil society actors including human rights defenders, journalists, and activists.” Amnesty International has documented how the Kenyan state has “systematically deployed technology-facilitated violence as part of a coordinated and sustained campaign to suppress Generation Z-led protests.” Africa Uncensored, an independent investigative media house in Kenya, produced a documentary investigating how Kenyan activists are tracked and surveilled.

In May 2025, the Citizen Lab found that Flexispy, a commercially available spyware tool, was installed on the devices of two Kenyan filmmakers while the devices were in police custody. Flexispy is a covert surveillance tool that monitors the activity on a phone including phone calls, text messages, the user’s location, and other sensitive information.

Troublingly, an investigation by Privacy International also found that Kenya’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) conducted warrantless wiretapping, then tipped off the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) to conduct “warranted” re-surveillance.

On January 30, 2026, Amnesty International issued a statement observing that, in Kenya, “[r]ecent years have seen growing concerns around state surveillance, particularly targeting journalists, digital activists, and protesters. Security agencies have reportedly monitored social media platforms, tracked online communications, and used digital tools to identify individuals involved in dissent.”

Cellebrite’s Responsibility for the Use of its Technology in Human Rights Violations

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights clearly specifies a responsibility on the part of businesses like Cellebrite, which sell surveillance technology to law enforcement and intelligence agencies, to ensure that their technology is not used to facilitate human rights abuses.

Multiple human rights organizations including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch,3 as well as the United Nations Human Rights Office, and the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, among others, have widely documented the Kenyan government’s widespread violation of human rights, including systematic crackdowns on peaceful protesters, the excessive and unnecessary use of force during protests, and the execution of arbitrary arrests and killings of protesters. The Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), an independent human rights watchdog in Kenya, has similarly reported receiving thousands of complaints in recent years about numerous human rights violations, including excessive use of force and violent disruption of peaceful protests.

Cellebrite’s Due Diligence?

Cellebrite has publicly stated that it “vets potential customers against internal human rights parameters, leading [the company] to historically cease business in jurisdictions where risks were deemed incompatible with [the company’s] corporate values.”

Yet, a quick online search would have revealed that the Kenyan authorities have engaged in widespread human rights violations. These numerous public reports should have raised alarm bells to Cellebrite’s officials that its highly invasive technology was at risk of abuse by police and security agencies in Kenya, and raises questions regarding the company’s due diligence procedures.

Conclusion: Cellebrite’s Global Abuse Problem

There are legitimate use cases for Cellebrite’s forensic collection and extraction technologies. But the context matters enormously. This latest case is part of a growing pattern pointing to the same conclusion: when a governmental agency with limited accountability obtains powerful technology for breaking into phones and extracting data, they are likely to abuse it. At the core of this latest investigation is an infringement on a Kenyan citizen’s fundamental rights to privacy, free expression, and assembly, facilitated by the extraction of private materials from their devices.

We sent Cellebrite questions about our past investigation of Cellebrite abuses in Jordan. Cellebrite’s answers to that report, provided through public relations firm Centropy PR, included only vague descriptions of internal protocols about its commitments. Cellebrite did not specify the processes it may have in place to determine whether security practices in a particular country comply with international human rights or domestic law or provide details on Cellebrite’s own ethical criteria for vetting customers.

While Cellebrite pointed to an “Ethics & Integrity Committee,” which allegedly vets government clients, it provided no details on what criteria may be used by this committee to vet clients or any other relevant processes. Nor did it provide any details on what measures, if any, are taken to investigate cases of abuse that are brought to light.

We have sent additional questions to Cellebrite about this investigation and will publish any responses we receive from them.

Cellebrite Linked to a Growing List of Reported Abuses

As Cellebrite continues to grow, so does the list of cases where the technology has been linked to abuses.

| Country | Reported Abuse(s) |

|---|---|

| Kenya | Cellebrite used to access the device of activist and politician Boniface Mwangi after arbitrary arrest and detention. (Source: forensic confirmation) |

| Jordan | Cellebrite used to access devices of multiple activists and civil society members while in police custody. (Source: forensic confirmation) |

| Serbia | Cellebrite used to access the device of investigative journalist Slaviša Milanov and a student protester while in police custody and at least one other unnamed individual. (Source: forensic confirmation) |

| Botswana | Cellebrite reportedly used to access the device of journalist Oratile Dikologang during his arbitrary arrest and detention. (Source) |

| Russia | Cellebrite is alleged to be widely used against activists and civil society members with at least two publicly documented cases of the use of Cellebrite’s UFED against opposition figure Lyubov Sobol and her cameraman Abdulkerim Abdulkerimov. The Russian Investigative Committee allegedly continued using Cellebrite tools even after Cellebrite announced it exited the country. (Source) |

| Indonesia | Cellebrite was reportedly used in investigations of citizens critical of the president and other officials. (Source) |

| Hong Kong | Cellebrite was reportedly used to access the devices of detained Hong Kong protesters. Cellebrite later stated that they would cease sales to the territory. (Source) |

| Myanmar | Cellebrite used to access the devices of two Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were detained for their Royhinga reporting. (Source) |

| Bahrain | Cellebrite was reportedly used to access the device and prosecute political dissident Mohammed al-Singace following his arbitrary arrest. There is also suspicion that Cellebrite’s technology was used to prosecute another Bahraini human rights defender, Naji Fateel. (Source) |

| Honduras | Cellebrite was reportedly used to extract material from the devices of environmental activists protesting the pollution of a local river by a chicken processing company. (Source) |

List of reported abuses of Cellebrite technology

In addition to the specific abuses listed in the table above, there are multiple other cases in which Cellebrite’s technology has been sold to autocratic regimes or security services notorious for human rights abuses.

Some Cellebrite Sales to Countries of Concern

| Bangladesh | Cellebrite sold to Rapid Action Battalion, a unit accused of torture and extrajudicial killings of journalists. (Source) |

| Belarus | Cellebrite has been sold to Belarus, a country that has engaged in widespread repression of protests, raising concern that the technology will be used against protesters. (Source) |

| Venezuela | Cellebrite reportedly sold its technology to Venezuelan authorities while they were under sanction. Venezuela’s government has been widely associated with human rights abuses and systematic repression of political expression. (Source) |

| Nigeria | Nigeria is reportedly a customer of Cellebrite. Forensic tools have been used to access the devices of several journalists during their arbitrary arrest and detention. (Source) |

| Saudi Arabia | Cellebrite was sold to Saudi Arabia despite a long and well-documented history of human rights abuses. (Source) |

| China | Cellebrite was extensively sold to Chinese authorities, despite widespread concerns over repression and human rights abuses. Cellebrite later stated that they would cease sales to the country. (Source) |

| Ghana | The U.S. and Interpol reportedly provided Cellebrite tools to the Ghanaian authorities, known for arresting journalists and searching their phones for sources. (Source) |

| Uganda | Cellebrite was sold to Uganda despite widespread reports of human rights abuses by security forces, including reports of individuals beaten to compel them to provide passcodes. (Source) |

| Philippines | Cellebrite was sold to agencies in the Philippines during a period marked by widespread human rights violations. (Source) |

| Vietnam | Cellebrite was sold to agencies in Vietnam despite extensively-documented human rights abuses, repression against the press, and a history of nonconsensual access to detainees’ devices. (Source) |

| Ethiopia | Cellebrite was sold to agencies in Ethiopia, which has a longstanding history of extensive human rights abuses. (Source) |

| Pakistan | Cellebrite was sold to agencies in Pakistan, despite documented human rights abuses and persecution of journalists. (Source) |

| India | Cellebrite was sold to the Delhi Police, despite a history of committing targeted surveillance against peaceful protesters. (Source) |

| Georgia | Georgia reportedly planned to renew their contract with Cellebrite, despite ongoing repression against pro-democracy protesters. The status of the contract is unclear. (Source) |

Sales of Cellebrite technology to certain countries of concern

In what has become an all-too-common feature of the surveillance industry marketplace, Cellebrite appears to sell its technology to a range of states that use the technology in violation of human rights. To ensure compliance with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, among other steps, Cellebrite should suspend its services to the relevant Kenyan agencies and conduct a thorough and transparent investigation into the use of its technology in human rights abuses in Kenya. It should also contribute to remedying these harms by publishing the results of this report, which would help to ensure that victims are provided with information regarding how their rights were violated and by whom.

Guidance to Civil Society on Device Seizure

At the time of writing, these are the Citizen Lab’s recommendations for individuals in civil society about managing risks from device seizure and Cellebrite-style forensic technology.

Protecting Against Device Seizure

If you are concerned that your device may be at risk of seizure, we recommend that you seek expert guidance. The following advice may also help reduce the likelihood that a forensic extraction tool will successfully bypass the device’s lock and access its data. It is important to note that these steps will not eliminate the likelihood of forensic access:

- Keep your device’s operating system up-to-date.

- Set a strong (preferably alphanumeric) passcode for your device.

- Enable Lockdown Mode (iPhones only).

- Enable Advanced Protection (available for Android version 16 or above).

And if you must carry data into a situation with elevated risk of device seizure (e.g., police station, border crossing), fully power off the device. Generally, we advise reducing the amount of sensitive data on mobile devices as they are more prone to seizure.

Has Your Device Been Seized?

First, we recommend immediately changing the passwords of all accounts that were on the device, including those accessed through the device’s browser(s). You should also check these accounts for logins that you do not recognize.

If the device was returned to you, we recommend seeking one-on-one advice from a qualified forensic professional to analyze the phone. If you are part of civil society, the Citizen Lab may be able to assist with forensic analysis. We can provide guidance on next steps or refer you to trusted partners for further support.

Seek Expert Assistance

If the device is returned to you, we strongly advise against deleting all of the data on your device (also known as a factory reset) before it is examined by an expert, as a factory reset will likely make it impossible to determine what occurred with the device when it was not in your custody. Such an examination may help to better understand what was done on the device, including identifying signs of the use of forensic tools such as Cellebrite’s technology. Such an analysis might also assist efforts to determine whether there was overreach or disproportionate use of forensic extraction tools in your case.

Participating in expert analysis can help uncover device vulnerabilities that may have been exploited by forensic extraction tools. Research groups like the Citizen Lab typically have a policy of notifying device manufacturers of these vulnerabilities, enabling them to develop and release patches for these exploits, making everyone’s devices more secure.

Acknowledgements

The Citizen Lab thanks Boniface Mwangi for graciously allowing us to forensically analyze artefacts from his device, and for consenting to the publication of our findings. Accountability for the abuse of intrusive technology begins with targets bravely coming forward. Without them, this work would not be possible.

We thank our colleagues, including Rebekah Brown and Kamel Al-Shawareb, for internal peer review and editorial suggestions.

Special thanks to Adam Senft, Alyson Bruce and Claire Posno for editorial support and publication assistance.

Special thanks to TNG.

- Kenya became a state party to the ICCPR in 1972. ↩︎

- See United Nations Human Rights Committee (UN HRC) General Comments 16, 34, 35, and 37. ↩︎

- Human Rights Watch’s associate Africa director, Otsieno Namwaya, reported that his house was under surveillance by Kenya’s Operation Support Unit, which is based within the Directorate of Criminal Investigations of the National Police Service. ↩︎