From Protest to Peril

Cellebrite Used Against Jordanian Civil Society

Illustration by DD

Through a multi-year investigation, we find that the Jordanian security apparatus has deployed forensic extraction products manufactured by Cellebrite against civil society devices. We release these findings alongside reporting from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) which includes interviews with a few of the victims.

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- 1. Background

- 2. Cellebrite: Forensic Extraction with a Growing Human Rights Problem

- 3. Forensically Confirming Cellebrite Abuses in Jordan

- 4. Court Records Expand the Scope of Cellebrite Abuse Cases

- 5. Cellebrite’s Responses

- 6. Conclusion: Cellebrite’s Tech Facilitates Human Rights Violations

- 7. Recommendations

- Appendix: Indicators of Compromise

Key Findings

- Cellebrite’s products have been used by the Jordanian authorities to extract data from the phones of activists and civil society members without their consent.

- During our forensic investigation of devices that were seized by authorities and returned to their owners, we uncovered iOS and Android Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) that we attribute with high confidence to Cellebrite’s forensic extraction products.

- Court records shared with the Citizen Lab indicate use of Cellebrite products in criminal prosecutions against activists and members of Jordanian civil society in a manner that does not comply with human rights treaties that Jordan has ratified (“abuse”).

- We present seven individual cases in this report. The Citizen Lab is aware of dozens of other cases in the country involving civil society. Forensic records obtained in previous testing rounds suggest authorities have been using Cellebrite since at least 2020.

Introduction

We forensically analyzed four devices belonging to Jordanian activists and human rights defenders seized by Jordanian authorities during detentions, arrests, and interrogations (and later returned). We also obtained three court records originating from criminal proceedings against activists and journalists under the 2023 Cybercrime Law. Each record includes a technical report prepared by Jordan’s Criminal Investigations Department that contains a summary of the forensic extraction conducted on the seized devices. The cases analyzed in this report occurred between late 2023 and mid-2025 in the context of protests in support of Palestinians in Gaza.

In total, we present seven different cases which lead us to conclude with high confidence that the seized devices were subjected to mobile forensic extraction using Cellebrite’s products. Forensic records obtained in previous testing rounds suggest Jordanian authorities have been using Cellebrite since at least 2020.

We release these findings alongside reporting from the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) which includes interviews with a few of the victims.

On December 29, 2025, the Citizen Lab and OCCRP sent letters to Cellebrite with a summary of findings. Cellebrite’s PR company responded to both Citizen Lab’s and OCCRP’s letters. On January 15, 2026, the Citizen Lab sent the PR company a follow-up letter with additional questions. We received a second response from Cellebrite. We share both responses here.

1. Background

Online Rights in Jordan

Over the past decade, civic space in Jordan has radically shrunk as authorities have deployed a growing range of legal and extralegal repressive measures against free expression. As of 2024, Freedom House ranked Jordan’s internet freedom as “partly free” and its state of freedom generally as “not free.” Successive Cybercrime Laws in 2015 and 2023 have been cornerstones of this repressive project.

Jordan’s 2015 and 2023 Cybercrime Laws

Upon its introduction, Jordan’s 2015 Cybercrime Law was extensively used to penalize online speech. Under the 2015 law, journalists, cartoonists, and activists were regularly summoned and detained for days, or even weeks, based on their social media posts or content they shared.

In mid-2023, the government repealed and replaced the Cybercrime Law, expanding its scope and punishments. The new law drew widespread criticism from human rights watchdogs and the United Nations (UN)’s High Commissioner for Human Rights for its broad and vague provisions and harsh fines. For example, Article 15 of Jordan’s 2023 Cybercrime Law criminalizes the sharing of “fake news” concerning national security and the public order, or content that “defames, slanders, or shows contempt for any individual.” Article 17 of the Cybercrime Law targets the sharing of content that “incites racism, sedition, hatred, violence, or insults religions,” without defining each term. Both articles have been widely used to prosecute political activists and dissidents in the country.

The 2023 Cybercrime law was introduced amidst rising political discontent over domestic and international issues. While Jordan and Israel normalized their relations in 1994, this normalization is deeply unpopular among the Jordanian public, more than half of whom are of Palestinian descent. Since October 2023, Jordanians have engaged in near daily protests in support of Palestinians in Gaza, with demonstrators frequently facing crackdowns and mass arrests. Indeed, the basis for many of the arrests was the 2023 law.

In a post on X dated March 12, 2025, the Jordanian Minister of Interior wrote the following in reference to Article 17:

“The most common cases handled daily [by the Cybercrime Unit] involve hate speech and inciting division and strife on social media. [In 2024], 244 cases of this nature were referred to the Public Prosecution, while 50 cases have been referred this year [2025]. According to the Cybercrime Law, penalties can reach up to three years in prison, a fine of 20,000 dinars [~28,200 USD], or both.”

In total, there were 2,928 prosecutions under Article 15 of the Cybercrime Law between September 12, 2023, and September 26, 2024, according to a report from Jordan’s National Centre for Human Rights, a National Human Rights Institution.

Police and Security Agencies

Jordan’s Cybercrime Unit, responsible for enforcing the Cybercrime Law, operates under the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) within the Public Security Directorate (PSD). The PSD’s director is overseen by Jordan’s Minister of Interior, whose ministry manages all policing and security functions.

Jordan’s intelligence agency, the General Intelligence Department (GID), known colloquially as the “Mukhabarat,” handles both foreign and domestic intelligence duties. In practice, the GID is also involved in law enforcement, and has been known to operate outside of judicial processes. Under Article 2 of law number 24 of 1964 (the “GID law”), the GID operates under the Prime Minister’s authority. The King of Jordan appoints the Prime Minister, the Director of the PSD, and the Director of the GID.

A History of Digital Surveillance Against Civil Society

The Citizen Lab and our partners at Front Line Defenders and Access Now have previously documented the abuse of surveillance technology against civil society in Jordan.

In 2022, we collaborated with Front Line Defenders to analyze Jordanian human rights lawyer Hala Ahed’s mobile device. We found evidence that she had been hacked with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware in March 2021. A few months later, we reported that four other devices belonging to Jordanian journalists and human rights defenders had also been infected with Pegasus.

In February 2024, in collaboration with Access Now and local organizations, we documented 35 additional cases of Pegasus infections in Jordan targeting human rights lawyers, activists, and journalists.

In total, the Citizen Lab and our partners have publicly identified 39 unique cases of Pegasus targeting in Jordan from 2019 through 2023.

2. Cellebrite: Forensic Extraction with a Growing Human Rights Problem

Cellebrite DI Ltd. (or Cellebrite) is an Israeli technology company that develops forensic tools, including the Universal Forensic Extraction Device (UFED) product series, which enables customers to extract all of a device’s data. These tools are sold to law enforcement agencies worldwide.

Non-Consensual Extraction

If authorities cannot compel device owners to handover a confiscated device’s passcode, companies like Cellebrite offer a range of tools to facilitate extracting data from devices. These products range from brute-force style attacks against passcodes to more advanced attacks that use exploits to bypass device security and encryption and access a device’s data. Even if authorities compel the owner of a confiscated device to provide their passcode, they still use tools like Cellebrite on the device to facilitate data extraction and visualization via software such as Cellebrite’s Physical Analyzer.

Two States for Phone’s Lock

When authorities confiscate a device, they tend to try and extract as much data from the device as possible. This data can include photos, videos, chats, files, saved passwords, location history, WiFi history, phone usage records, web history, email, and social media accounts, third-party applications’ data, and sometimes data that the phone’s user has attempted to delete.

One factor that often affects the amount of data that can be extracted from a phone is the phone’s lock state. There are generally two possible lock states to a device: Before First Unlock (BFU) or After First Unlock (AFU).

Before First Unlock (BFU)

After a phone is rebooted (i.e., restarted) but before it is unlocked for the first time since that restart, the phone is in BFU state. In BFU, a meaningful portion of private information on the phone is typically in an encrypted state, and generally cannot be decrypted without knowledge of the PIN/passcode or encryption keys. Forensic extraction tools like Cellebrite might be unable to access this information, unless a suitable security vulnerability exists within the phone.

While the exploits used by Cellebrite and its competitors to access phones in a BFU state are closely guarded secrets, older phones can sometimes be accessed using public vulnerabilities, such as the checkm8 vulnerability in the iPhone’s BootROM, which allows an attacker to load untrusted code at boot time. We are aware of public exploits, such as checkra1n, that can leverage this vulnerability against many iPhone devices that use an A11 or earlier chip (e.g., iPhone X and older), though the vulnerability is still present in the A12 and A13 chips.

After First Unlock (AFU)

After a phone has been unlocked for the first time, and then re-locked, it goes into AFU state. Here, the phone typically does not benefit from the same encryption and protections as in BFU state. However, if the phone is locked, exploits may still be needed to access it.

For devices in AFU, Cellebrite’s tools might leverage software vulnerabilities that can be triggered via the device’s physical port (e.g., USB-C or Lightning). Because phones are designed to support a large number of uncommon and often obscure USB-connected accessories, it is likely that exploitable bugs exist in the code responsible for handling such accessories. Such bugs are often not prioritized by defensive security researchers because they cannot be triggered remotely (such as in the case of zero-click attacks).

On iOS, Apple has implemented a default mitigation called “USB Restricted Mode” to try and prevent attackers from trivially accessing such drivers (though this feature is not immune from bypasses, such as CVE-2025-24200). A similar feature called “USB Protection” exists for Android phones with Advanced Protection enabled (available for Android 16+). Modified versions of Android, such as GrapheneOS, have also implemented a similar mitigation.

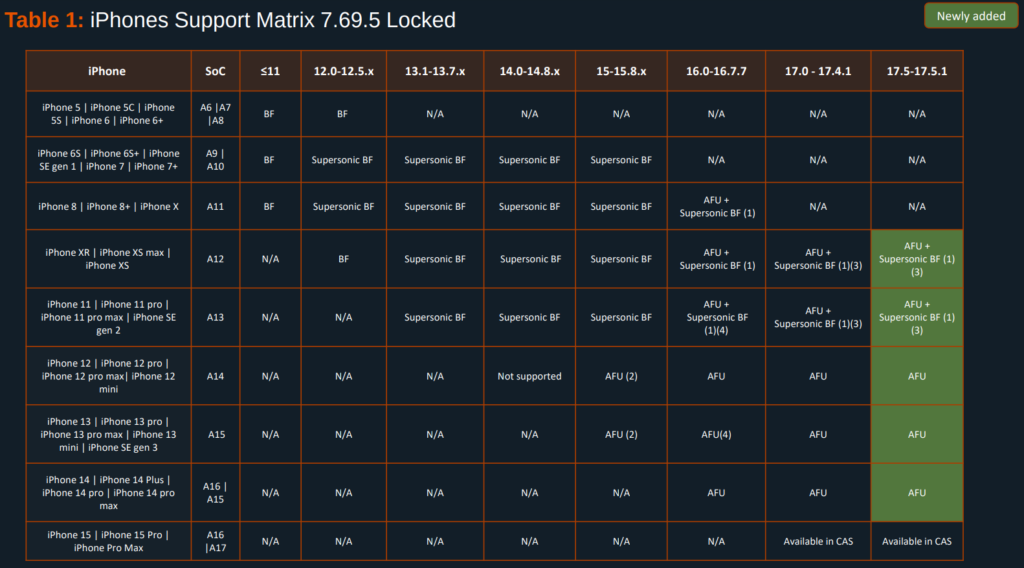

Multiple leaks have revealed Cellebrite’s abilities to access and extract data from phones, mapping which bypasses and extraction types are available for each device and OS version. The leaks indicate that Cellebrite’s capabilities are more limited on device BFU.

Inactivity Reboots

In late 2024, Apple introduced a security feature in iOS 18 whereby an iPhone would automatically reboot (restart) after 3 consecutive days (or 72 hours) of inactivity, taking a phone’s state from AFU to BFU. A similar optional feature was introduced on Android phones in April 2025 for Google Play services version 25.16.

Growing Reports of Cellebrite Abuse

Cellebrite’s sales to governments and law enforcement agencies with track records of human rights abuse in places like Bangladesh (Rapid Action Battalion), Belarus, China, Hong Kong, Russia, Uganda, the United States (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement), and Venezuela have raised serious concerns. In a 2021 filing to the United States Securities and Exchange Commission, Cellebrite admitted that their products can be used in violation of human rights and acknowledged that revelations of abuse “could adversely affect […] revenue and results of operations.” More recently, human rights groups and technical teams have uncovered specific abuses of Cellebrite products against civil society, or to further repression.

Reports of Cellebrite Abuses

Cellebrite products have reportedly been used to extract data from the phones of Reuters journalists jailed in Myanmar for reporting on the Rohingya massacre, a journalist in Botswana, and may have been used against journalists’ devices in Nigeria. In Indonesia, Cellebrite products were reportedly used to target dissidents. Authorities in Russia have also reportedly used Cellebrite’s products against the devices of pro-democracy activists and dissidents. In 2025, it was reported that Cellebrite had been used against the devices of anti-deportation activists in Italy.

Human rights activists raised concerns that the notoriously repressive Belarusian authorities might be using Cellebrite technology during the crackdown on widespread anti-regime protests in 2020.

Forensically-Confirmed Abuses

In 2024, Amnesty International’s Security Lab published forensic evidence indicating that Serbian authorities had used Cellebrite to unlock devices of members of a think tank and a protest organizer in Serbia. After the devices were unlocked, authorities sideloaded spyware onto the devices. Amnesty International’s Security Lab recovered crash logs from the devices that pointed to several vulnerabilities in Android USB kernel drivers.

Cellebrite’s Responses

In response to pressure and concerns, Cellebrite has reportedly cancelled contracts with specific customers including the Bangladeshi Rapid Action Battalion, as well as countries like China. They similarly announced that they were halting operations in Russia and Belarus.

However, since core features of Cellebrite’s products can be operated without the need for an internet connection, they continue to be used in places like Russia. Indeed, the Russian authorities boasted that they continued to use Cellebrite’s products to extract data from the cellphones of detainees a year after Cellebrite halted sales.

Similarly, Cellebrite’s ability to control the flow of their technology to repressive security services is also in doubt. In 2020, Cellebrite also announced that it would halt sales in China and Hong Kong, but Chinese police have reportedly continued to acquire Cellebrite products.

3. Forensically Confirming Cellebrite Abuses in Jordan

Between January 2024 and June 2025, we collected and forensically analyzed three iPhones and one Android device belonging to members of Jordanian civil society that had been detained, arrested or interrogated by the authorities. This set included the devices of two political activists, a student organizer, and a human rights defender. We conclude with high confidence that all four devices were subjected to forensic extraction with a Cellebrite product. In addition, our analysis surfaced high-confidence, and previously-unpublished, Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) of Cellebrite forensic extraction on iOS and Android devices.

Due to fear of reprisals, all individuals have requested anonymity. Accordingly, we provide as many details as possible about each case without compromising their identities. All individuals were enrolled in a research ethics protocol reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto.

Analyzing iPhones Extracted with Cellebrite

Case 1: Political Activist

| Context that led to device seizure: | Interrogation |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Political activism and participation in protests |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | No |

We forensically analyzed the iPhone of a political activist whose device was seized following an interrogation by Jordan’s General Intelligence Department (GID).

Forensic Findings

Forensic artefacts from the device show that the phone was accessed through Cellebrite a week after it was seized. The phone remained in custody for a total of 35 days.

We find that, during the time the phone was in possession of the GID, the iPhone was connected via USB to a device that identified itself with the HostID 9016926980658937761372207 and SystemBUID 30313996-42072961236303456. We attribute both to Cellebrite with high confidence, as they appear in DLL files digitally signed by Cellebrite on VirusTotal, including “CellebriteMobileAgent/iPhoneLib.dll.”

handle_pair: Pair message: {

PairRecord = {

DeviceCertificate = [..]

HostCertificate = [..]

HostID = 9016926980658937761372207;

ProtocolVersion = 2;

RootCertificate = [..]

SystemBUID = “30313996-42072961236303456”;

};

Request = Pair;

}

We found the same HostID on multiple other iPhones that we analyzed and that were seized during this time period.

Case 2: Student Organizer

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Student activism |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | Yes |

We forensically analyzed the iPhone 15 of a student activist who was detained and taken for interrogation at GID premises. The iPhone was running the latest version of iOS (17.4.1) at the time.

During interrogation, the activist refused to provide their passcode to the officers, who then unlocked it using Apple’s biometric face ID by holding it up to the activist’s face. The activist was separated from their phone and taken to the Cybercrime Unit on the same day. The next morning they were taken to prison.

Upon their release, the activist went to pick up their phone from the Cybercrime Unit and found their device’s passcode written on a piece of tape stuck to the back of their phone. Face ID was also disabled. The activist never provided the passcode throughout their interrogation and detention, and were surprised to find their passcode written on a piece of tape stuck to the back of the phone.

Forensic Findings

We are unable to conclude the manner in which the phone was unlocked. The phone had a 6-digit passcode. Forensic records show that the device rebooted a day prior to forensic extraction with Cellebrite and was therefore in a Before First Unlock (BFU) state prior to extraction. BFU is the state in which a device has not been unlocked following a restart. A phone’s contents are more securely encrypted when a device is in BFU state than when it is in AFU (After First Unlock).

While the phone was seized, we observed that the device was connected to an external device that we attribute to Cellebrite based on the HostID and SystemBUID. Moreover, we note that the phone was connected to two separate networks during its seizure, both of which geolocate to the then-location of the Cybercrime Unit in Amman, Jordan.

‘wifi.network.ssid.TP-LINK_50A270’: {…, ‘LocationLatitude’: 31.958680104962223,…, ‘LocationLongitude’: 35.91743559847752},…},

‘wifi.network.ssid.Galaxy M510CE6′: {…,’LocationLatitude’: 31.958980876368322,…,

‘LocationLongitude’: 35.91784241761346},…},

Case 3: Activist and Researcher

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Political activism and participation in protests |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | No |

We inspected another seized iPhone, vulnerable to the public checkm8 exploit. The iPhone contained a crashlog that showed a process called mnm had run on the device. The phone had apparently been booted from a RAMdisk, indicating that secure boot had been defeated, perhaps via checkm8. The panic showed that the process mnm had a dispatch queue labelled “com.cellebrite.bruteforce.”

“24” : {…,”procname”:”mnm”,…,”dispatch_queue_label”:”com.cellebrite.bruteforce”,…}

We also noted that several NVRAM variables beginning with “mnm-” were set on the phone (NVRAM variables can be used as a way to preserve state between device reboots outside of the filesystem). We thus attribute the process name mnm or NVRAM variables beginning with “mnm-” to Cellebrite’s tool with high confidence.

Analyzing Androids Extracted with Cellebrite

Case 4: Human Rights Defender

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Online posts provoking “sedition or strife” |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | Yes |

Upon analyzing the forensic records of an Android belonging to a human rights defender, we found traces of one package with the ID com.client.appA installed one day following the device’s seizure. The package was deleted shortly afterwards. We attribute the package com.client.appA to Cellebrite with high confidence, because this package name appears in DLL files digitally signed by Cellebrite on VirusTotal, including “CellebriteMobileAgent\CellewiseLib.dll.”

START DELETE PACKAGE: observer{██████████}

pkg{com.client.appA}, user{█}, caller{█} flags{█}

START INSTALL PACKAGE: observer{██████████}

stagedDir{/data/app██████████.tmp}

stagedCid{null}

pkg{com.client.appA}

Request from{null}

package=com.client.appA totalTimeUsed=”00:24″ lastTimeUsed=██████████

totalTimeVisible=”00:26″ lastTimeVisible=██████████

lastTimeComponentUsed=██████████ totalTimeFS=”00:00″ lastTimeFS=”1970-01-01 02:00:00″ appLaunchCount=2 fgServiceLaunchCount=0

The human rights defender was called in for questioning by the Jordanian Cybercrime Unit and was subsequently detained. The individual was eventually convicted by a criminal court under Article 17 of the Cybercrime Law for “provoking sedition or strife” and was fined 5,000 Jordanian Dinars (~7,000 USD). The charges stemmed from posts on X in which the person criticized Arab countries’ foreign policy positions towards Israel.

Notably, despite forensic evidence confirming that the individual’s device underwent Cellebrite extraction, the specific extraction methodology was not indicated in the court records we obtained. Court records only stated that law enforcement had already found sufficient evidence to indict the individual at the time of the initial seizure of the device. The court records describe that law enforcement took manual screenshots from the human rights defender’s device, which they later attached to their report which was filed in court.

In other similar cases, which we detail below, court records do indicate the use of Cellebrite technology in the technical examination reports presented by the Digital Evidence Branch of the Criminal Investigations Department (CID). This, along with the cases presented above and the nature of the individuals (political activists, human rights defenders, journalists, and student organizers), provides insight into the frequency with which law enforcement’s use of Cellebrite violates international human rights law.

4. Court Records Expand the Scope of Cellebrite Abuse Cases

While forensic evidence provides a high-confidence confirmation that Cellebrite was abused to non-consensually extract data from the devices of Jordanian activists and human rights defenders, analysis of court records shared with the Citizen Lab provides additional information, expanding the scope of what we know about how Cellebrite is abused to target civil society. All court records originate from proceedings involving criminal prosecutions against activists, journalists, and civil society members in Jordan under the 2023 Cybercrime Law.

Case 5: Youth Activist

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Online posts denouncing police violence in protests and mass arrest campaigns |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | Yes |

A youth activist was summoned by the Cybercrime Unit over Facebook stories and a Facebook post allegedly criticizing government actions against protesters and activists. They were later charged under Articles 15 and 17 of the 2023 Cybercrime Law.

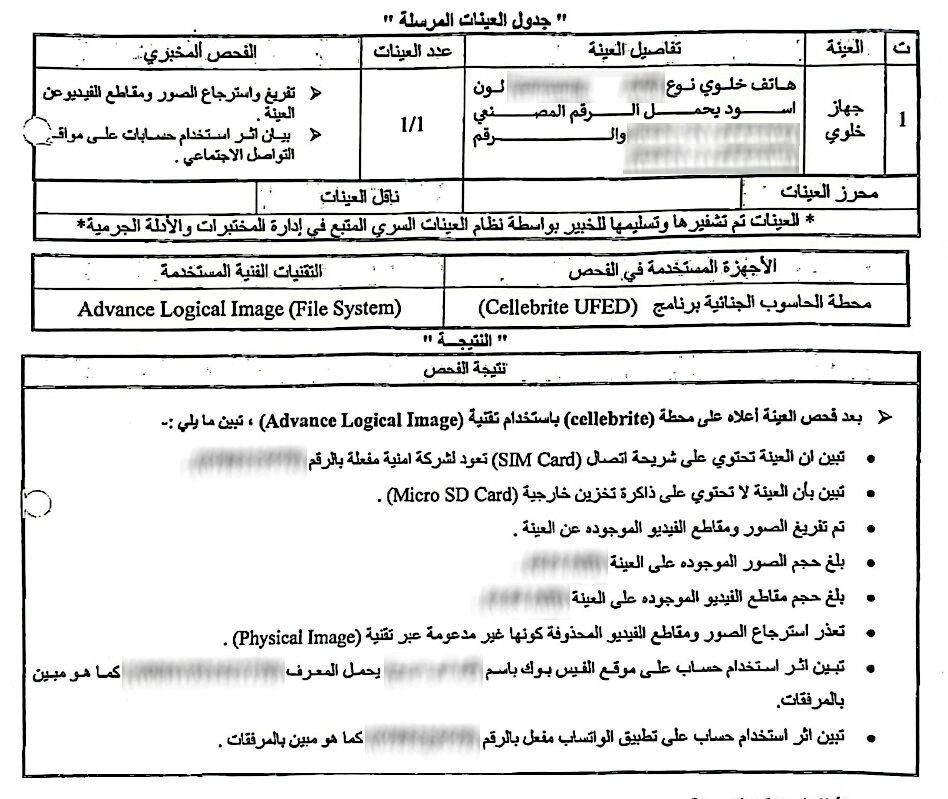

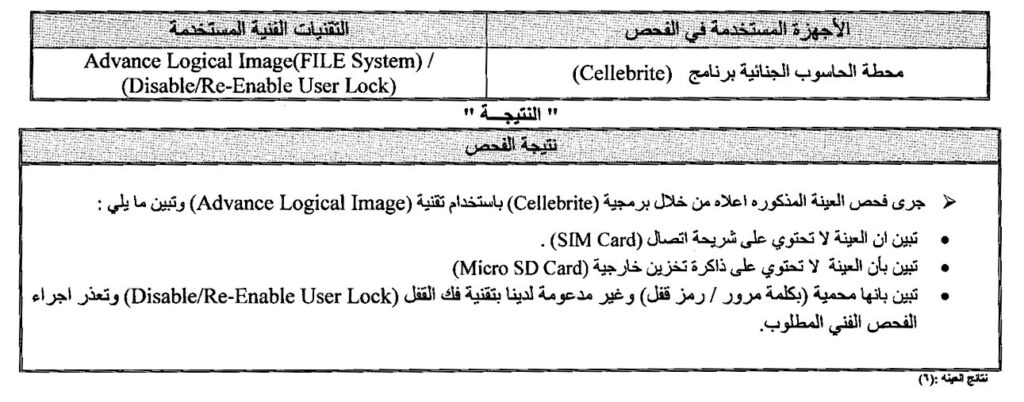

Court records, which include a technical examination report submitted by the Digital Evidence Branch of the Criminal Investigations Department, show that Cellebrite technology was used. The case file notes the use of Cellebrite technology in an attempt to detect traces of the suspected social media account allegedly used to share the “incriminating” content as well as photos and video clips. Ultimately, the Cybercrime Unit concluded that no traces of the account were found on the submitted device. The technical report also notes that deleted images and videos could not be extracted, as this feature is unavailable through the “Physical Image” method.

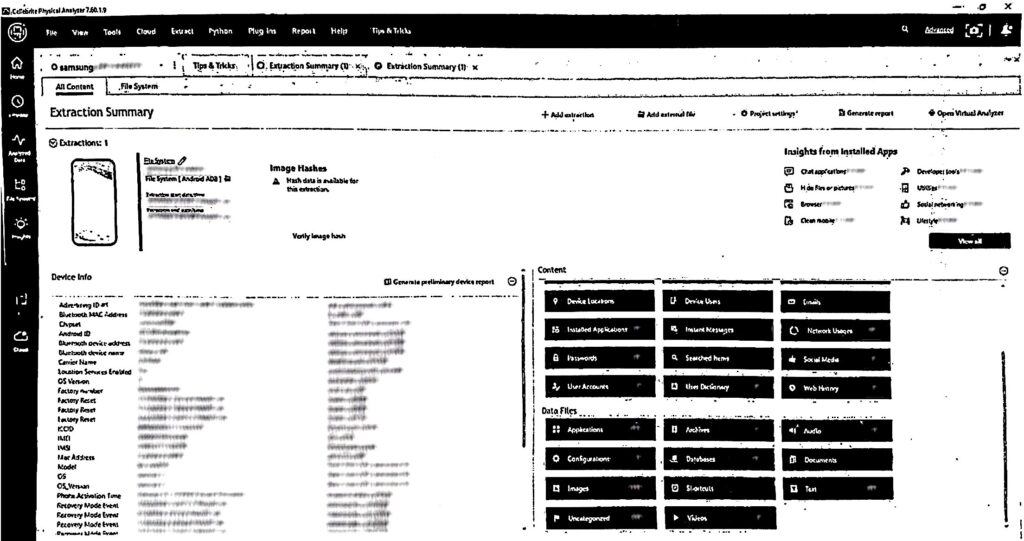

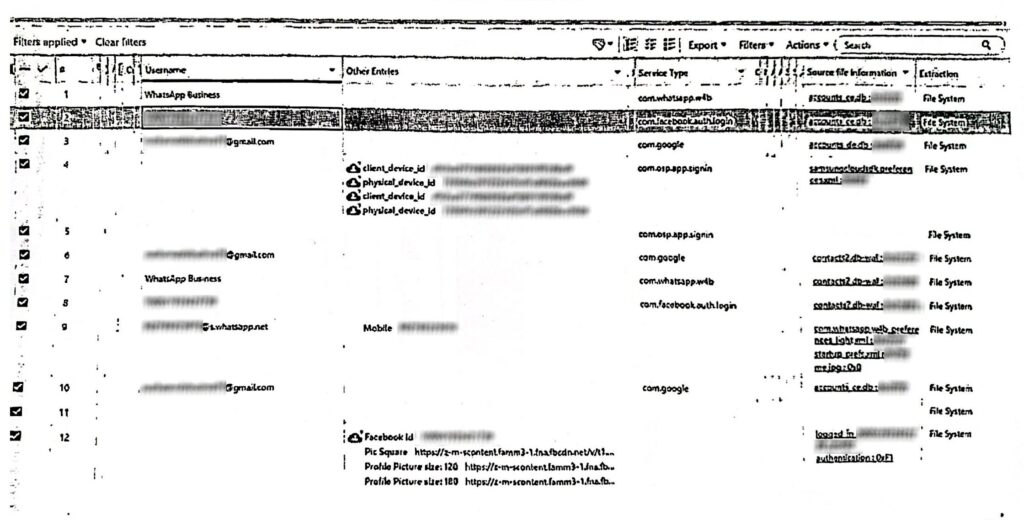

Court records show that the Cybercrime Unit only required a single piece of evidence in order to proceed with their case against the youth activist, which is proof that the seized device is logged into the social media account containing the posts deemed “criminal.” Nevertheless, the Unit still proceeded with an “Advanced Logical Image” extraction. According to Cellebrite’s website, this method combines both logical and file system extractions into a single process. In other words, they extracted all data from the device, even though they only needed to determine whether a specific Facebook account is or was present on the device.

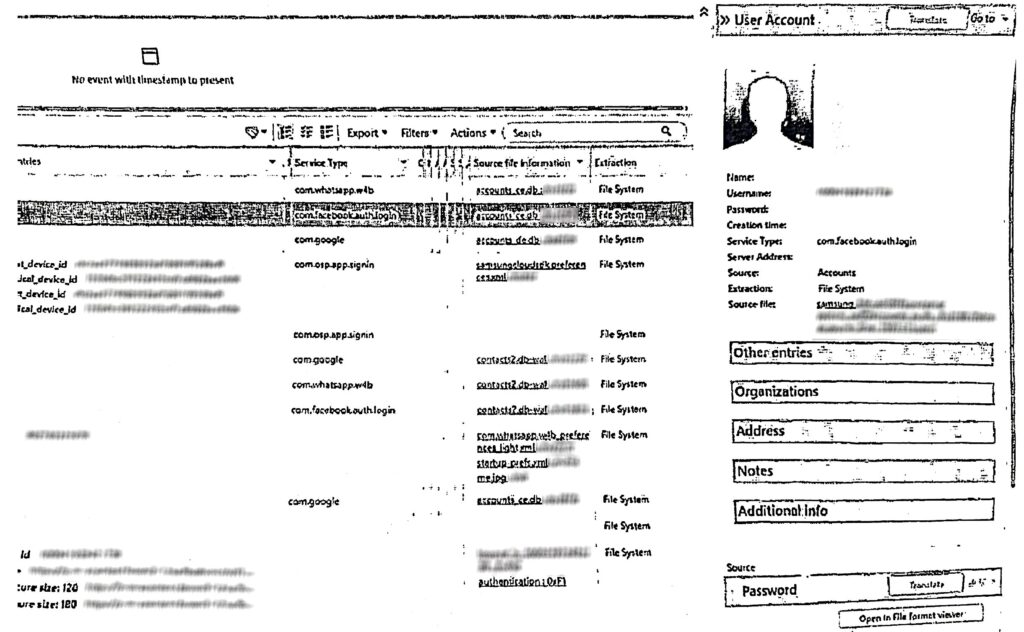

This finding is further corroborated by screenshots provided in court records showing the summary dashboard generated by the Cellebrite extraction (Figure 4). The dashboard displays the number of images, videos, passwords, and emails extracted, as well as the IDs of other social media accounts. While the numbers next to each data point (e.g., Email – 3, User Accounts – 11, Documents – 1492) were blurred for privacy, the categories and overall structure remain visible.

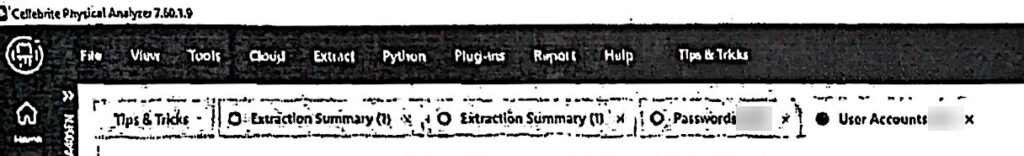

Zooming in on the court records shared with the Citizen Lab and specifically screenshots displaying results from the Cellebrite extraction (Figure 7), we observe a few open tabs in the Cellebrite Physical Analyzer dashboard, including one labeled “Passwords.” This suggests that the unit examining the device may have viewed or intended to view data outside the scope of the case, underscoring the intrusiveness of the search.

Screenshots also show that the Digital Evidence Branch was using Cellebrite Physical Analyzer version 7.60.1.9 at the time.

Case 6: Citizen Journalist

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Online posts denouncing police violence in protests |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | Yes |

A citizen journalist summoned by the Cybercrime Unit over a social media post allegedly denouncing police violence in protests was charged under article 15 of the 2023 Cybercrime Law.

The technical examination report submitted by the Digital Evidence Branch also shows the use of Cellebrite to attempt an Advanced Logical Image of the seized device. However, in the results section, the branch notes its inability to bypass the device’s passcode using the “Disable/Re-Enable User Lock” feature provided by Cellebrite. In this case, the individual did not volunteer the passcode.

Case 7: Activist

| Context that led to device seizure: | Detention |

| Alleged justification provided by authorities: | Online posts about a planned strike |

| Was the Cybercrime Law invoked? | Yes |

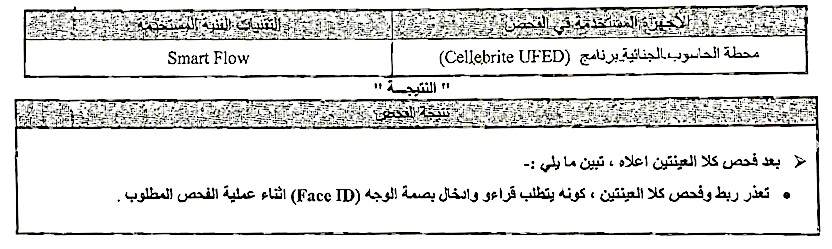

In another court record shared with the Citizen Lab, the department responsible for running extraction on the seized devices stated that they were unable to proceed (with extraction) as both devices seized required a biometric unlock (face ID in this case). We assume that the iPhones had Stolen Device Protection enabled, which prevents certain actions on the devices even if the passcode is known.

Device Seizure Scenarios

During our research, individuals from Jordanian civil society who approached us for forensic testing shared what had led to their devices being seized. Below we list some common scenarios and decision-making patterns undertaken by individuals.

Called In for Questioning

In some cases, individuals receive a call from the Police Security Department (PSD), requesting they report to the Cybercrime Unit for interrogation. At this stage, the individual is usually unaware of the nature of the investigation. However, a common behaviour we observed is that these individuals review their online activity and communications, primarily to identify anything that might have attracted the attention of online patrols. They also often delete posts and messages that they believe could potentially cause trouble or lead to incrimination. These are understandable actions given Jordan’s expansive and vaguely defined cybercrime laws that are used to target and repress freedom of expression.

Once at the Cybercrime Unit, officers present the arrested individual with a post or social media profile that allegedly violates the Cybercrime Law and proceed to interrogate them about the content, specifically whether they are the author, or whether they are behind the account that authored the posts.

It is at this point that officers may compel individuals to hand over their mobile devices for search and seizure. Once in the investigator’s hands, the officer asks the individual to unlock the device by providing the passcode. Officers pressure individuals to comply by either: 1) asking them to spell out the passcode, or 2) requesting that they write it down on a piece of paper, or 3) instructing them to type it out on their phone in front of the officers so they can take note of it. In a few cases that we are aware of, individuals have refused to hand over their passcode. As noted above, in one case, police used Face ID to unlock a device while the person was physically restrained.

Confiscation Without Warning

We note a few cases where security forces confiscated an individual’s device in the context of interrogation and protests. In those cases, police forcefully took the phone from the individual’s hands without asking them to handover the device.

Broadly, devices are seized either: 1) with the individual’s prior knowledge, typically when a charge is filed by the public prosecutor and the individual’s device(s) are seized as part of the evidence; and 2) without the individual’s prior knowledge, when the individual is unexpectedly arrested (e.g., in a protest, during a house raid, or during interrogation).

5. Cellebrite’s Responses

The Citizen Lab contacted Cellebrite to provide them with an opportunity to comment on our findings. Steven George-Hilley, the CEO of Centropy Public Relations, responded to our email with the following statement:

“…A Cellebrite Spokesperson said:

“Ethical and lawful use of our technology is paramount to our mission of protecting nations, communities and businesses around the world.

As a global provider of digital investigation technologies, adherence to the rule of law and privacy standards are fundamental elements of all our relationships. As a matter of policy, we do not comment on specifics.

Our commitment to transparency is underlined by the fact we have a publicly declared independent Ethics & Integrity Committee, which is comprised of many external industry specialists.”

We note that this response does not deny any of our findings, nor does it explain whether Cellebrite’s Ethics & Integrity Committee will take up this matter.

On January 15, 2026, we sent Mr. George-Hilley a follow-up with additional questions and a pledge to publish in full any response we receive. On January 19, 2026, we received the following response.

6. Conclusion: Cellebrite’s Tech Facilitates Human Rights Violations

In this report, we contribute to the body of evidence that technology like Cellebrite’s UFED is commonly found amongst repressive states’ toolboxes and used to further their surveillance objectives against civil society. While forensic tools are distinct from mercenary spyware, autocratic regimes show similar creativity in using them for repression.

We present evidence showing Jordan is a customer of Cellebrite. Our analysis uncovered forensic traces of the use of Cellebrite technology on several devices seized from civil society actors by the country’s security apparatus. We learn through forensic research that this practice has been present for at least five years (since 2020) and confirm through court records shared with the Citizen Lab that the use of the tool – which has been deployed against members of Jordanian civil society – likely violates international human rights law.

Cellebrite Forensic Tools and Human Rights Principles

Jordan, which has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) among other regional and international human rights treaties, is required to comply with international human rights law and the principles of legality, legitimacy, necessity, and proportionality. Under international human rights law, there are strict limitations on the targeting of political dissidents and civil society actors (such as human rights defenders and journalists) with surveillance technology.

As the UN Human Rights Committee (UN HRC) expressed in General Comment No. 34, restrictions on freedom of expression:

“…may never be invoked as a justification for the muzzling of any advocacy of multi-party democracy, democratic tenets and human rights. Nor, under any circumstance, can an attack on a person, because of the exercise of his or her freedom of opinion or expression, including such forms of attack as arbitrary arrest, torture, threats to life and killing, be compatible with article 19.”

The UN HRC further emphasized that unlawful restrictions on the right to freedom of expression of journalists and human rights defenders are particularly common, noting:

“Journalists are frequently subjected to such threats, intimidation and attacks because of their activities. So too are persons who engage in the gathering and analysis of information on the human rights situation and who publish human rights-related reports, including judges and lawyers. All such attacks should be vigorously investigated in a timely fashion, and the perpetrators prosecuted, and the victims, or, in the case of killings, their representatives, be in receipt of appropriate forms of redress.”

These principles were recently reaffirmed by the UN HRC in Djakupova v. Kyrgyzstan, where the treaty body emphasized that “in circumstances of public debate concerning public figures in the political domain and public institutions, the value placed by the Covenant upon uninhibited expression is particularly high” and that “a free, uncensored and unhindered press or other media, including Internet news portals, as in this case, is essential in any society to ensure freedom of opinion and expression and the enjoyment of other Covenant rights. This implies a free press and other media able to comment on public issues without censorship or restraint and to inform public opinion. It constitutes one of the cornerstones of a democratic society.”

Thus, the use of technology to extract data from the phones of persons subjected to such unlawful criminal prosecutions or in response to their lawful exercise of the right to freedom of expression cannot meet the requirements of international human rights law and cannot be justified. In the cases described in this report, all individuals targeted with Cellebrite’s technology were engaging in expression that would be considered lawful under international human rights law. This includes peaceful participation in protests, expressions of dissent, and denouncing police violence. The fact that some individuals were subject to a prosecution under the domestic Cybercrime law does not mean that such a use of Cellebrite’s technology complies with international human rights law standards. The Jordanian authorities would need to demonstrate that the use of the technology was compliant with international human rights law principles.

In addition to human rights violations by Jordanian authorities, Cellebrite fails to comply with its responsibilities as articulated in the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Under this framework, firms that sell surveillance technology to law enforcement and intelligence agencies have a responsibility to ensure that their technology is not misused or abused by their clients. However, numerous investigations by the Citizen Lab and others over the last 15 years have shown that few firms in the surveillance industry have in place any effective due diligence or controls to prevent such misuses. Similar to spyware, forensic data extraction technologies enable actors to collect highly-invasive data from individuals’ devices. As this case has demonstrated, if such tools are in the hands of poorly regulated government security agencies, they can enable repression of what is otherwise legitimate expression or assembly. Indeed, Cellebrite has in the past publicly acknowledged that its products “may be used by customers in a way that is, or that is perceived to be, incompatible with human rights.”

Cellebrite’s Responses: Vague & Generic

As part of this investigation, we sent representatives of Cellebrite a letter and offered to publish in full their response. On January 12, 2026, we received a response from Cellebrite’s PR company. We responded on January 15, 2026, with an additional set of questions about these cases, and their human rights policies and procedures to which we received a response on January 19, 2026.

In response to our questions, Cellebrite’s public relations firm stated that the company refuses to “comment on specifics as a matter of policy,” even after we asked Cellebrite whether they can waive this policy in order to enable victim accountability.

It is particularly telling that, to date, Cellebrite has offered only vague and unsubstantiated answers to our correspondence, which fail to meet the requirements of the UN Guiding Principles that companies “have in place policies and processes through which they can both know and show that they respect human rights in practice” and which require “providing a measure of transparency and accountability to individuals or groups who may be impacted and to other relevant stakeholders, including investors.”

7. Recommendations

Cellebrite: be transparent, open an investigation

We call on Cellebrite to open an investigation on its clients in Jordan in light of the human rights abuses uncovered in this report. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights require businesses to formally address how they handle the risk of severe human rights impacts, including providing “information that is sufficient to evaluate the adequacy of an enterprise’s response to the particular human rights impact involved.”

Cellebrite: watermark by default

In our letters requesting a response to our findings, we asked Cellebrite about whether they would consider watermarking devices that had been forensically imaged with a unique identifier specific to a particular customer. We believe that such an action would aid in the investigation of potential abuses, and facilitate accountability for a specific customer engaged in an abuse. Such watermarking would also discourage illegal and covert use of Cellebrite tools, and provide Cellebrite with a key signal of responsibility should they choose to investigate a reported abuse.

For individuals whose device is at risk of forensic extraction

If your device was seized, we recommend immediately changing the passwords of all accounts that were on the device, including those accessed through the device’s browser(s). You should also check these accounts for logins that you do not recognize. If the device was returned to you, we recommend seeking one-on-one advice from a qualified forensic professional to analyze the phone. If you are part of civil society, the Citizen Lab may be able to assist with forensic analysis. We can provide guidance on next steps or refer you to trusted partners for further support.

We strongly advise against deleting all of the data on your device (also known as a factory reset) before it is examined by an expert, as a factory reset will likely make it impossible to determine what occurred with the device when it was not in your custody. Such an examination may help to better understand what was done on the device, including identifying signs of the use of forensic tools such as Cellebrite’s technology. Such an analysis might also assist efforts to determine whether there was overreach or disproportionate use of forensic extraction tools in your case.

Moreover, participating in expert analysis can help uncover device vulnerabilities that may have been exploited by forensic extraction tools. Research groups like the Citizen Lab typically have a policy of notifying device manufacturers of these vulnerabilities, enabling them to develop and release patches for these exploits, making everyone’s devices more secure.

If you are concerned that your device may be at risk of seizure, we recommend that you seek expert guidance. The following advice may also help reduce the likelihood that a forensic extraction tool will successfully bypass the device’s lock and access its data. It is important to note that these steps will not eliminate the likelihood of forensic access:

- Keep your device’s operating system up-to-date.

- Set a strong (preferably alphanumeric) passcode for your device.

- Enable Lockdown Mode (iPhones only).

- Enabled Advanced Protection (available for Android version 16 or above).

And if you must carry data into a situation with elevated risk of device seizure (e.g., police station, border crossing), fully power off the device. Generally, we advise reducing the amount of sensitive data on mobile devices as they are more prone to seizure.

For application developers

- For messaging application developers, implement a feature that allows users to remove a member from a group (in case that member’s device is seized).

- For social media application developers, enable a feature that allows properly authenticated users to remotely disable their account and lock a particular device out from it.

For developers of operating systems

- Research the feasibility of duress PINs (or the ability to wipe the contents of the phone upon entering a specific PIN on the lock screen).

- Introduce a USB restricted mode across operating systems.

For organizations operating helplines handling digital security matters

If someone reaches out inquiring support following device seizure, it is important to advise the individual against doing a factory reset on the device, as doing so will typically erase all traces and make it impossible for forensic analysts to determine what occurred with the device during seizure.

Below are a series of questions that can aid your investigation and the support you can offer:

- What type of device was seized? (OS and possibly version)

- How long was the device seized for?

- Which date was it seized in and when was it returned?

- Include the exact day, month, and year.

- If possible (and if the individual seeking support remembers), note the time of seizure and return as well (in local time).

- Which date was it seized in and when was it returned?

- What state was the device in when it was seized?

- Was the device protected by a passcode at the time of seizure?

- If so, how long and complex was the passcode?

- Did the authorities that seized the device request the passcode?

- Did the individual handover the device’s passcode to the authorities?

- Was the device turned on or turned off at the time of seizure?

- If turned on, was it unlocked at least once prior to seizure or just restarted? (AFU or BFU)

- If the device was turned on and in AFU, was it locked or unlocked upon seizure?

- If the device was turned on and in AFU, was biometric lock enabled?

- Was the device protected by a passcode at the time of seizure?

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Luis Fernando Garcia and an anonymous contributor for reviewing this report. We would also like to thank Mostafa Al-A’sar for providing an Arabic translation of this report.

Appendix: Indicators of Compromise

iOS Lockdown Records

Host ID: 9016926980658937761372207

System BUID: 30313996-42072961236303456

iOS Crash Logs

Process name: mnm

Service name: com.cellebrite.bruteforce

Android Package

Package ID: com.client.appA