Introduction

The FinFisher Suite is described by its distributors, Gamma International UK Ltd., as “Governmental IT Intrusion and Remote Monitoring Solutions.” 1 The toolset first gained notoriety after it was revealed that the Egyptian Government’s state security apparatus had been involved in negotiations with Gamma International UK Ltd. over the purchase of the software. Promotional materials have been leaked that describe the tools as providing a wide range of intrusion and monitoring capabilities.2 Despite this, however, the toolset itself has not been publicly analyzed.

This post contains analysis of several pieces of malware obtained by Vernon Silver of Bloomberg News that were sent to Bahraini pro-democracy activists in April and May of this year. The purpose of this work is identification and classification of the malware to better understand the actors behind the attacks and the risk to victims. In order to accomplish this, we undertook several different approaches during the investigation.

As well as directly examining the samples through static and dynamic analysis, we infected a virtual machine (VM) with the malware. We monitored the filesystem, network, and running operating system of the infected VM.

This analysis suggests the use of “Finspy”, part of the commercial intrusion kit, Finfisher, distributed by Gamma International.

Delivery

This section describes how the malware was delivered to potential victims using e-mails with malicious attachments.

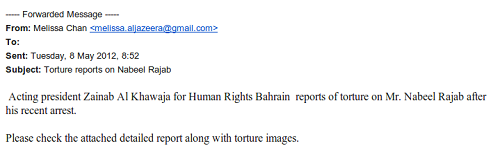

In early May, we were alerted that Bahraini activists were targeted with apparently malicious e-mails. The emails ostensibly pertained to the ongoing turmoil in Bahrain, and encouraged recipients to open a series of suspicious attachments. The screenshot below is indicative of typical message content:

The attachments to the e-mails we have been able to analyze were typically .rar files, which we found to contain malware. Note that the apparent sender has an e-mail address that indicates that it was being sent by “Melissa Chan,” who is a real correspondent for Aljazeera English. We suspect that the e-mail address is not her real address.3 The following samples were examined:

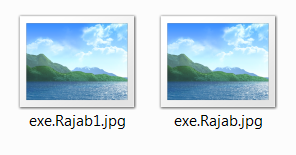

These contained executables masquerading as picture files or documents:

The emails generally suggested that the attachments contained political content of interest to pro-democracy activists and dissidents. In order to disguise the nature of the attachments a malicious usage of the “righttoleftoverride” (RLO) character was employed. The RLO character (U+202e in unicode) controls the positioning of characters in text containing characters flowing from right to left, such as Arabic or Hebrew. The malware appears on a victim’s desktop as “exe.Rajab1.jpg” (for example), along with the default Windows icon for a picture file without thumbnail. But, when the UTF-8 based filename is displayed in ANSI, the name is displayed as “gpj.1bajaR.exe”. Believing that they are opening a harmless “.jpg”, victims are instead tricked into running an executable “.exe” file.4

Upon execution these files install a multi-featured trojan on the victim’s computer. This malware provides the attacker with clandestine remote access to the victim’s machine as well as comprehensive data harvesting and exfiltration capabilities.

Installation

This section describes how the malware infects the target machine.

The malware displays a picture as expected. This differs from sample to sample. The sample “Arrested Suspects.jpg” (“gpj.stcepsuS detserrA.exe”) displays:

It additionally creates a directory (which appears to vary from sample to sample):

It copies itself there (in this case the malware appears as “Arrested Suspects.jpg”) where it is renamed:

Then it drops the following files:

It creates the folder (the name of which varies from host to host):

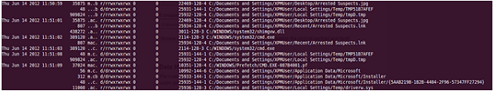

This process is observable on the filesystem timeline of the infected host (click image to enlarge):

“driverw.sys” is loaded and then “delete.bat” is run which deletes the original payload and itself. It then infects existing operating system processes, connects to the command and control server, and begins data harvesting and exfiltration.

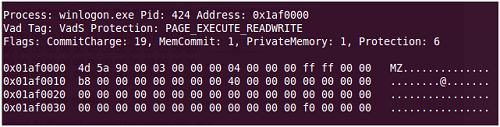

Examining the memory image of a machine infected with the malware shows that a technique for infecting processes known as “process hollowing” is used. For example, the memory segment below from the “winlogon.exe” process is marked as executable and writeable:

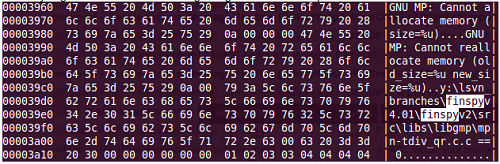

Here the malware starts a new instance of a legitimate process such as “winlogon.exe” and before the process’s first thread begins, the malware de-allocates the memory containing the legitimate code and injects malicious code in its place. Dumping and examining this memory segment reveals the following strings in the infected process:

Note the string:

This file seems to correspond to a file in the GNU Multi-Precision arithmetic library:

http://gmplib.org:8000/gmp/file/b5ca16212198/mpn/generic/tdiv_qr.c

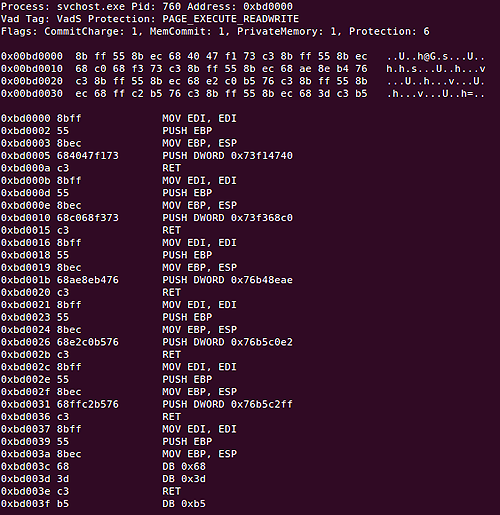

The process “svchost.exe” was also found to be infected in a similar manner:

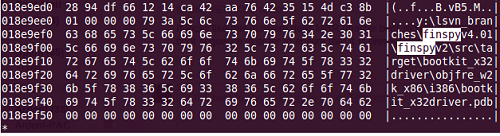

Further examination of the memory dump also reveals the following:

This path appears to reference the functionality that the malware uses to modify the boot sequence to enable persistence:

A pre-infection vs post-infection comparison of the infected VM shows that the Master Boot Record (MBR) was modified by code injected by the malware.

The strings found in memory “finspyv4.01” and “finspyv2” are particularly interesting. The FinSpy tool is part of the FinFisher intrusion and monitoring toolkit.5

Obfuscation and Evasion

This section describes how the malware is designed to resist analysis and evade identification.

The malware employs a myriad of techniques designed to evade detection and frustrate analysis. While investigation into this area is far from complete, we discuss several discovered methods as examples of the lengths taken by the developers to avoid identification.

A virtualised packer is used. This type of obfuscation is used by those that have “strong motives to prevent their malware from being analyzed”.6

This converts the native x86 instructions of the malware into another custom language chosen from one of 11 code templates. At run-time, this is interpreted by an obfuscated interpreter customized for that particular language. This virtualised packer was not recognised and appears to be bespoke.

Several anti-debugging techniques are used. This section of code crashes the popular debugger, OllyDbg.

This float value causes OllyDbg to crash when trying to display its value. A more detailed explanation of this can be found here.

To defeat DbgBreakPoint based debuggers, the malware finds the address of DbgBreakPoint, makes the page EXECUTE_READWRITE and writes a NOP on the entry point of DbgBreakPoint.

The malware checks via PEB to detect whether or not it is being debugged, and if it is it returns a random address.

The malware calls ZwSetInformationThread with ThreadInformationClass set to 0x11, which causes the thread to be detached from the debugger.

The malware calls ZwQueryInformationProcess with ThreadInformationClass set to 0x(ProcessDebugPort) and 0x1e (ProcessDebugObjectHandle) to detect the presence of a debugger. If a debugger is detected it jumps to a random address. ZwQueryInformationProcess is also called to check the DEP status on the current process, and it disables it if it’s found to be enabled.

The malware deploys a granular solution for Antivirus software, tailored to the AV present on the infected machine. The malware calls ZwQuerySystemInformation to get ProcessInformation and ModuleInformation. The malware then walks the list of processes and modules looking for installed AV software. Our analysis indicates that the malware appears to have different code to Open/Create process and inject for each AV solution. For some Anti-Virus software this even appears to be version dependent. The function “ZwQuerySystemInformation” is also hooked by the malware, a technique frequently used to allow process hiding:

Data Harvesting and Encryption

This section describes how the malware collects and encrypts data from the infected machine.

Our analysis showed that the malware collects a wide range of data from an infected victim. The data is stored locally in a hidden directory, and is disguised with encryption prior to exfiltration. On the reference victim host, the directory was:

“C:\Windows\Installer\{49FD463C-18F1-63C4-8F12-49F518F127}.”

We conducted forensic examination of the files created in this directory and identified a wide range of data collected. Files in this directory were found to be screenshots, keylogger data, audio from Skype calls, passwords and more. For the sake of brevity we include a limited set of examples here.

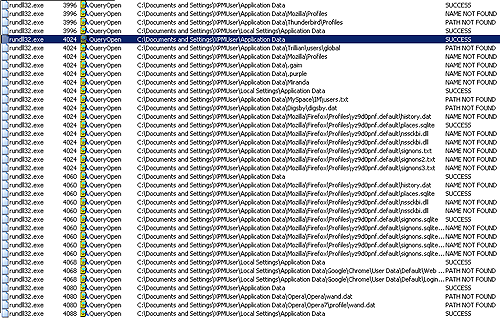

The malware attempts to locate the configuration and password store files for a variety browsers and chat clients as seen below (click image to enlarge):

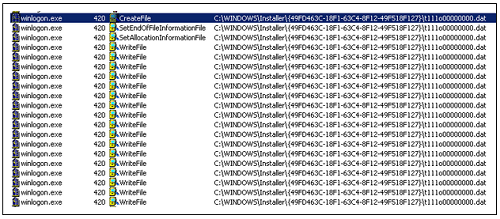

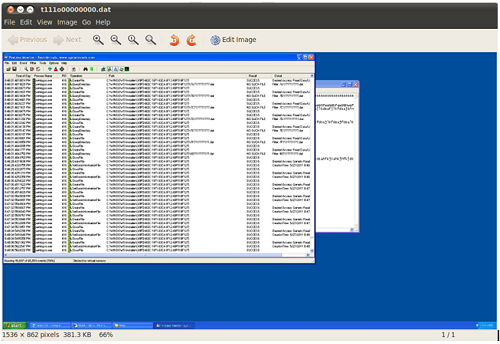

We observed the creation of the file “t111o00000000.dat” in the data harvesting directory, as shown in the filesystem timeline below:

The infected process “winlogon.exe” was observed writing this file via Process Monitor (click image to enlarge):

Examination of this file reveals that it is a screenshot of the desktop (click image to enlarge):

Many other modules providing specific exfiltration capabilities were observed. Generally, the exfiltration modules write files to disk using the following naming convention: XXY1TTTTTTTT.dat. XX is a two-digit hexadecimal module number, Y is a single-digit hexadecimal submodule number, and TTTTTTTT is a hexadecimal representation of a unix timestamp (less 1.3 billion) associated with the file creation time.

Encryption

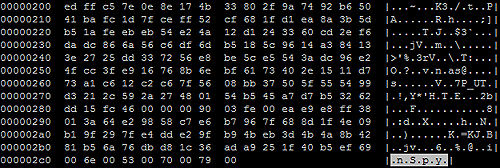

The malware uses encryption in an attempt to disguise harvested data in the .dat files intended for exfiltration. Data written to the files is encrypted using AES-256-CBC (with no padding). The 32-byte key consists of 8 readings from memory address 0x7ffe0014: a special address in Windows that contains the low-order-4-bytes of the number of hundred-nanoseconds since 1 January 1601. The IV consists of 4 additional readings.

The AES key structure is highly predictable, as the quantum for updating the system clock (HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Services\W32Time\Config\LastClockRate) is set to 0x2625A hundred-nanoseconds by default, and the clock readings that comprise the key and IV are taken in a tight loop:

The following AES keys were among those found to be used to encrypt records in .dat files. The first contains the same 4 bytes repeated, whereas in the second key, the difference between all consecutive 4-byte blocks (with byte order swapped) is 0x2625A.

In all, 64 clock readings are taken. The readings are encrypted using an RSA public key found in memory (whose modulus begins with A25A944E) and written to the .dat file before any other encrypted data. No padding is used in the encryption, yielding exactly 256 encrypted bytes. After the encrypted timestamp values, the file contains a number of records encrypted with AES, delimited by EAE9E8FF.

In reality, these records are only partially encrypted: if the record’s length is not a multiple of 16 bytes (the AES block size), then the remainder of the bytes are written to the file unencrypted. For example, after typing “FinSpy” on the keyboard, the keylogger module produced the following (trailing plaintext highlighted):

The predictability of the AES encryption keys allowed us to decrypt and view these partially-encrypted records in full plaintext. The nature of the records depends on the particular module and submodule. For example, submodule Y == 5 of the Skype exfiltration module (XX == 14), contains a csv representation of the user’s contact list:

Submodule Y == 3 records file transfers. After a Skype file transfer concludes, the following file is created: %USERPROFILE%\Local Settings\Temp\smtXX.tmp. This file appears to contain the sent / received file. As soon as smtXX.tmp is finished being written to disk, a file (1431XXXXXXXX.dat) is written, roughly the same size as smtXX.tmp. After sending a picture (of birdshot shotgun shell casings used by Bahrain’s police) to an infected Skype client, the file 1431028D41FD.dat was observed being written to disk. Decrypting it revealed the following:

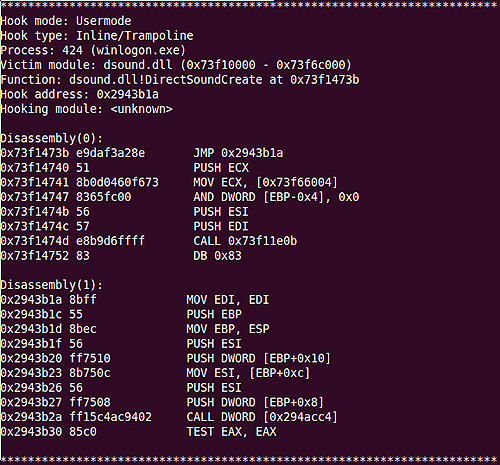

Additionally, submodule Y == 1 records Skype chat messages, and submodule Y == 2 records audio from all participants in a Skype call. The call recording functionality appears to be provided by hooking DirectSoundCaptureCreate:

Command and Control

This section describes the communications behavior of the malware.

When we examined the malware samples we found that they connect to a server at IP address 77.69.140.194

WHOIS data7 reveals that this address is owned by Batelco, the principal telecommunications company of Bahrain:

For a period of close to 10 minutes, traffic was observed between the infected victim and the command and control host in Bahrain.

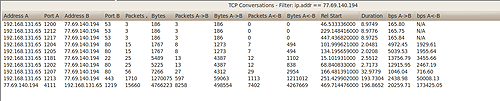

A summary of the traffic by port and conversation size (click image to enlarge):

The infected VM talks to the remote host on the following five TCP ports:

Based on observation of an infected machine we were able to determine that the majority of data is exfiltrated to the remote host via ports 443 and 4111.

Conclusions about Malware Identification

Our analysis yields indicators about the identity of the malware we have analyzed: (1) debug strings found the in memory of infected processes appear to identify the product and (2) the samples have similarities with malware that communicates with domains belonging to Gamma International.

Debug Strings found in memory

As we previously noted, infected processes were found containing strings that include “finspyv4.01” and “finspyv2” (click image to enlarge):

Publicly available descriptions of the FinSpy tool collected by Privacy International among others and posted on Wikileaks8 make the a series of claims about functionality:

- Bypassing of 40 regularly tested Antivirus Systems

- Covert Communication with Headquarters

- Full Skype Monitoring (Calls, Chats, File Transfers, Video, Contact List)

- Recording of common communication like Email, Chats and Voice-over-IP

- Live Surveillance through Webcam and Microphone

- Country Tracing of Target

- Silent Extracting of Files from Hard-Disk

- Process-based Key-logger for faster analysis

- Live Remote Forensics on Target System

- Advanced Filters to record only important information

- Supports most common Operating Systems (Windows, Mac OSX and Linux)

Shared behavior with a sample that communicates with Gamma

The virtual machine used by the packer has very special sequences in order to execute the virtualised code, for example:

Based on this we created a signature from the Bahrani malware, which we shared with another security researcher who identified a sample that shared similar virtualised obfuscation. That sample is:

The sample connects to the following domains:

The domain tiger.gamma-international.de has the following Whois information9:

Martin Muench is a representative of Gamma International, a company that sells “advanced technical surveillance and monitoring solutions”. One of the services they provide is FinFisher: IT Intrusion, including the FinSpy tool. This labelling indicates that the matching sample we were provided may be a demo copy a FinFisher product per the domain ff-demo.blogdns.org.

We have linked a set of novel virtualised code obfuscation techniques in our Bahraini samples to another binary that communicates with Gamma International IP addresses. Taken alongside the explicit use of the name “FinSpy” in debug strings found in infected processes, we suspect that the malware is the FinSpy remote intrusion tool. This evidence appears to be consistent with the theory that the dissidents in Bahrain who received these e-mails were targeted with the FinSpy tool, configured to exfiltrate their harvested information to servers in Bahraini IP space. If this is not the case, we invite Gamma International to explain.

Recommendations

The samples from email attachments have been shared with selected individuals within the security community, and we strongly urge antivirus companies and security researchers to continue where we have left off.

Be wary of opening unsolicited attachments received via email, skype or any other communications mechanism. If you believe that you are being targeted it pays to be especially cautious when downloading files over the Internet, even from links that are purportedly sent by friends.

Acknowledgements

Malware analysis by Morgan Marquis-Boire and Bill Marczak. Assistance from Seth Hardy and Harry Tuttle gratefully received.

Special thanks to John Scott-Railton.

Thanks to Marcia Hofmann and the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF).

We would also like to acknowledge Privacy International for their continued work and graciously provided background information on Gamma International.

Footnotes

1 http://www.finfisher.com/

2 http://owni.eu/2011/12/15/finfisher-for-all-your-intrusive-surveillance-needs/#SpyFiles

3 http://blogs.aljazeera.com/profile/melissa-chan

4 This technique was used in the recent Madi malware attacks.

5 http://www.finfisher.com/

6 Unpacking Virtualised Obfuscators by Rolf Rolles – http://static.usenix.org/event/woot09/tech/full_papers/rolles.pdf

7 http://whois.domaintools.com/77.69.140.194

8 E.g. http://wikileaks.org/spyfiles/files/0/289_GAMMA-201110-FinSpy.pdf

9 http://whois.domaintools.com/gamma-international.de

Media coverage

The Wall Street Journal

Slate

CSO

Tech Week Europe

Bloomberg

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Privacy International

Spiegel Online

PC Mag

The New York Times