Key Findings

- In this report we track a malware operation targeting members of the Tibetan Parliament over August and October 2016.

- The operation uses known and patched exploits to deliver a custom backdoor known as KeyBoy.

- We analyze multiple versions of KeyBoy revealing a development cycle focused on avoiding basic antivirus detection.

- This operation is another example of a threat actor using “just enough” technical sophistication to exploit a target.

Introduction

The Tibetan community has been targeted for over a decade by espionage operations that use malware to infiltrate communications and gather information. They are often targeted simultaneously with other ethnic minorities and religious groups in China. Examples as early as 2008 document malware operations against Tibetan non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that also targeted Falun Gong and Uyghur groups. More recently in 2016, Arbor Networks reported on connected malware operations continuing to target these same groups, which the Communist Party of China perceives as a threat to its power.

These types of operations have multiple components, each with their own associated costs to the operator. There is the exploit code and malware used to gain access to systems, the infrastructure that provides command and control to the malware operator, and the human elements – developers who create the malware, operators who deploy it, and analysts who extract value from the stolen information.

We anticipate that operators will attempt to balance the amount of information they expect to gather with the operational costs and risks of deploying different strategies and technologies. For example, in deploying a particular malware implant against a target the operator will balance the likelihood and cost of discovery with the perceived value of extracting information from that target. If a toolkit is exposed inadvertently, the target may increase defenses and the operator will have to spend more time and resources on development.

Civil society groups, due to their generally limited technical capacity and lack of security expertise and countermeasures, shift the risk/reward ratio in ways favourable to the malware operator. For example, we have observed frequent reuse of older (patched) exploits in malware operations against the Tibetan community. Up-to-date operating systems and software would block these threats, but the operators have probably discovered through experience that the their targets have unpatched systems and a general lack of security controls beyond antivirus programs. The continued use of old exploits is a cost reduction strategy: since they still work, there is little need to use more expensive exploits.

Moreover, many of the malware defenses used by the Tibetan diaspora involve individuals recognizing signs of a malicious email, such as exhortations to open attachments. This kind of behavioral strategy pushes the operators to change their social engineering tactics, but does not provide pressure to radically change their toolkits. This situation is different from a technical-indicator based institutional security environment. In practice, minimal code changes sufficient to bypass signature-based security controls such as antivirus may be all that are necessary.

This report analyzes an operation targeting members of the Tibetan Parliament. The actors used a new version of “KeyBoy,” a custom backdoor first disclosed by researchers at Rapid7 in June 2013. Their work outlined the capabilities of the backdoor, and exposed the protocols and algorithms used to hide the network communication and configuration data.

We observed operations in August and October 2016, shortly after an order in June to demolish the Larung Gar Buddhist Academy and days before organized protests on October 19 around the same issue. These operations involved highly targeted email lures with repurposed content and attachments that contained an updated version of KeyBoy. We assess that KeyBoy is the product of a development cycle that is iterated only as much as necessary to ensure the survival of the implant against antivirus detection and basic security controls.

This report is divided into two parts:

Part 1: The Parliamentarian Operation Analyzes an operation targeting the members of the Tibetan Parliament by repurposing legitimate content, and documents implanted with Keyboy.

Part 2: KeyBoy – Tracking Evolution Examines the KeyBoy development cycle revealing a focus on avoiding basic antivirus detection.

To assist other researchers, we include appendices and indicators of compromise that detail the KeyBoy samples we analyzed and provide an in-depth analysis of some features of the most recent implant.

Part 1: The Parliamentarian Operation

In August and October 2016 we observed a malware operation targeting members of the Tibetan Parliament (the highest legislative organ of the Tibetan government in exile, formally known as Central Tibetan Administration). We collected two emails sent to Parliamentarians that rapidly repurposed legitimate content in an attempt to entice recipients to open malicious documents. The first attempt leveraged an old vulnerability in the parsing of Rich-text-format (.rtf) files (CVE-2012-0158). The second attempt used a newer, but also patched, .rtf vulnerability (CVE-2015-1641). Both attempts used versions of KeyBoy and shared the same command and control infrastructure as well as other configuration details.

Attempt 1

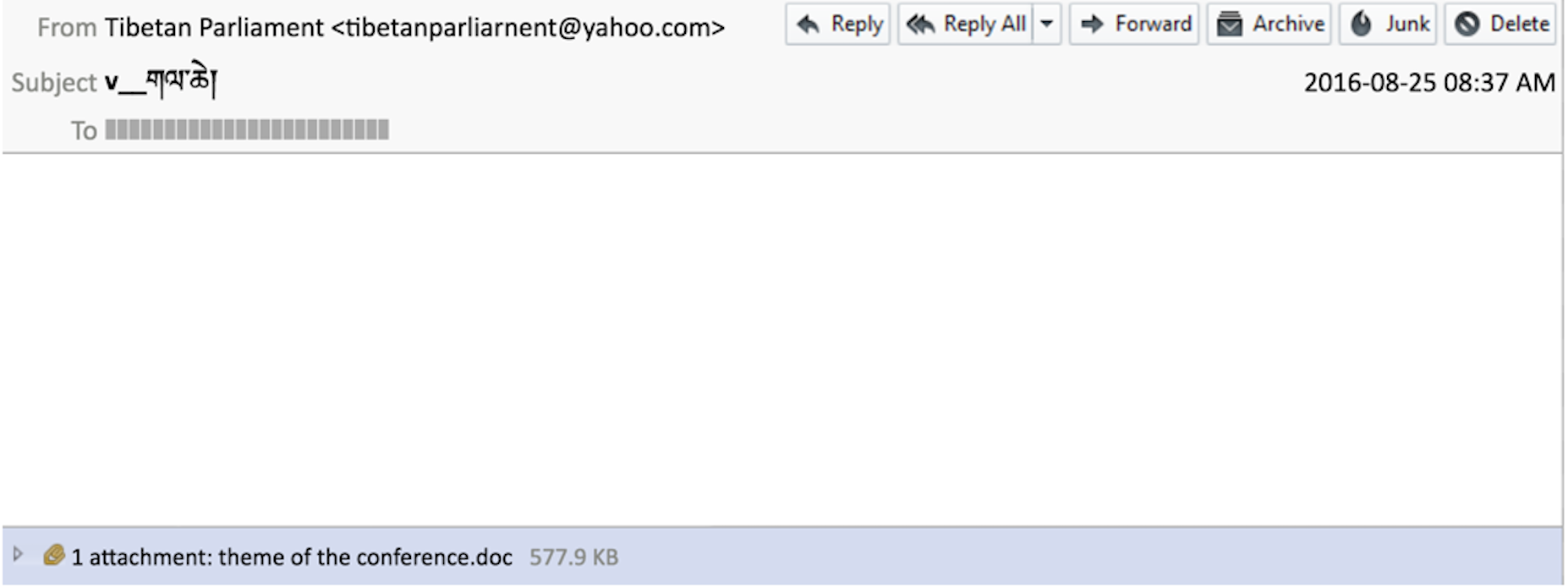

On August 25, 2016, members of the Tibetan Parliament received an email with information on an upcoming conference relevant to the Tibetan community. This email had the same subject and attachment as a legitimate message sent to the same recipients just 15 hours prior, but in this case the attachment was crafted to exploit a frequently targeted vulnerability in Microsoft Office. The accompanying malware was a backdoor implant designed to surveil the computers of the Parliamentarians. This malicious attachment used the original, legitimate filename as a decoy (see: Figure 1).

This level of targeting and re-use of a legitimate document sent only hours before shows that the actors behind the operation are closely watching the Tibetan community, and may have already compromised the communications of one or more of the Parliamentarians.

Opening the attachment (an apparently blank document) in Microsoft Word would result in the infection of the target system with the KeyBoy implant.

The Infection Chain

The email attachment is a .rtf document containing a dropper, delivered using an exploit designed to leverage CVE-2012-0158, a vulnerability in the way that Microsoft Word handles .rtf files. Over the past four years, this vulnerability has been consistently used in malware campaigns against the Tibetan community despite having been patched since April 2012.

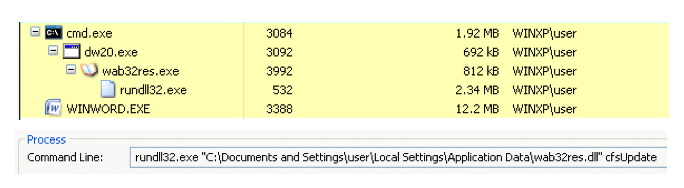

If the exploit is successful, the following infection chain (see: Figure 2) is observed on the system.

The files in this infection chain are outlined below. The exploit launches an executable ‘dropper’ component which is responsible for placing the malware payload and its configuration file on disk, and finally for launching the main malware code.

Note that the dropper and the final (DLL) payload were compiled within seconds of each other.

Next, the dropper places a renamed copy of the legitimate Windows Address Book executable, along with the malware binary, wab32res.dll, in the Local Application Data directory. Notably, the dropper modifies the timestamps of the configuration file and the payload to match those of the \Microsoft\SystemCertificates\My\ directory within the user’s Local Application Data directory. Once these files are written to disk, the dropper starts the Windows Address Book executable which loads and executes the malicious wab32res.dll file via DLL search-order hijacking.

Attempt 2

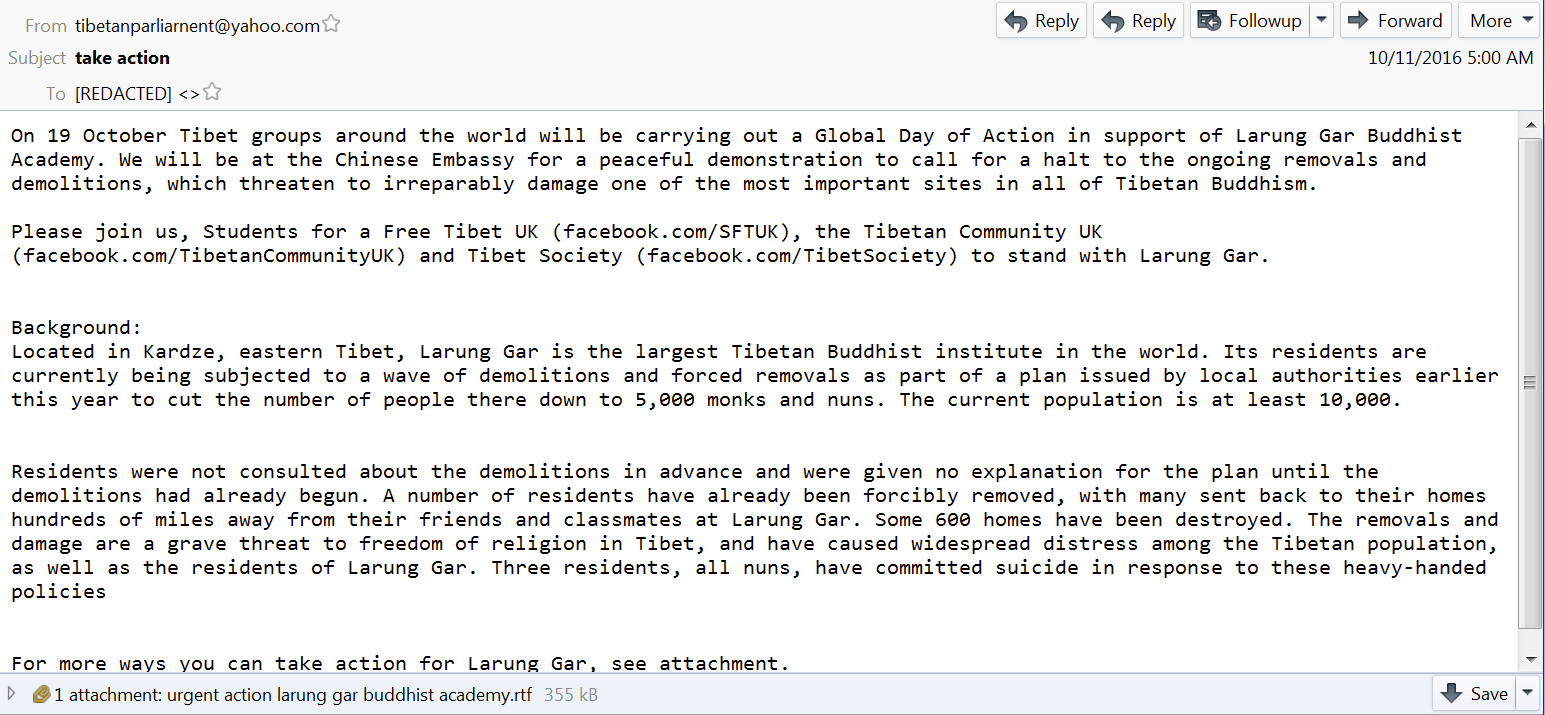

On October 11, 2016, the Tibetan Parliamentarians received an email with content repurposed from a Tibetan activism campaign protesting the demolition of a Buddhist monastery in Tibet. The email was sent from the same email address as the previous attempt (tibetanparliarnent[@]yahoo.com) and appears to copy content from the Facebook page of a Tibetan NGO promoting the campaign. The message urges recipients to open an attached .rtf file with further details on the campaign (see: Figure 3).

Opening the attachment (an apparently blank document) in Microsoft Word would, similar to the first attempt, result in the infection of the target system with the KeyBoy implant.

The Infection Chain

The .rtf document attached to the malicious email was designed to exploit a more recent vulnerability: CVE-2015-1641. If successful, this exploit launches a newer version of the same malware used in the August attempt outlined above, using a similar infection chain.

As with the first attempt, the resulting dropper installs the malware payload into the Local Application Data directory as wab32res.dll and subsequently launches it using the same method of DLL search-order hijacking against the legitimate Windows Address Book executable.

A Note on Vulnerabilities

The two .rtf vulnerabilities targeted in these exploitation attempts, CVE-2012-0158 and CVE-2015-1641, are among a set of four .rtf vulnerabilities discussed in recent reporting from researchers at Arbor Networks.

The researchers describe the presumed existence of an exploit document ‘builder’ designed to selectively weaponize .rtf files using four older, patched, vulnerabilities: CVE-2012-0158, CVE-2012-1856, CVE-2015-1641, and CVE-2015-1770.

The Arbor report describes the ongoing use of these four vulnerabilities in a series of espionage campaigns against not only Tibetan groups, but also others related to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Uyghur interests. While we have not connected the campaign targeting the Tibetan Parliamentarians to the campaigns described by Arbor, the continual pairing of these older .rtf vulnerabilities with malware operations against the Tibetan community is noteworthy.

The Malware

The malware samples deployed in both of these operations are updated versions of the KeyBoy backdoor first discussed in 2013 by Rapid7. KeyBoy provides basic backdoor functionality, allowing the operators to select from various capabilities used to surveil and steal information from the victim machine.

KeyBoy functionality:

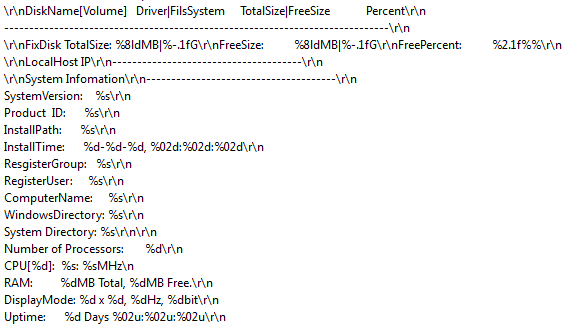

- Gather system information, including details of the operating system, processor, disk, memory, display, and uptime (see: Figure 4)

- Upload files to the victim computer

- Download files from the victim computer

- Browse the file system, including gathering details about attached drives

- Execute commands and applications

- Launch interactive shell

These updated versions of KeyBoy make use of an encoded configuration file to store their command and control (C2) information along with other required settings. In both cases, the dropper wrote this configuration file in the user’s Local Application Data directory as win32res.dat. After analyzing these malware samples, we were able to decode the following configuration parameters, presented in Table 1

| Line | Description | First sample | Second sample |

| Line 1 | Identity code, used to ensure config was correctly decoded | 9876543210 | 9876543210 |

| Line 2 | C2 Server #1 (hostname/ip) | 45.125.12[.]147 | 45.125.12[.]147 |

| Line 3 | C2 Server #2 (hostname/ip) | 103.40.102[.]233 | 45.125.12[.]147 |

| Line 4 | C2 Server #3 (hostname/ip) | 45.125.12[.]147 | 45.125.12[.]147 |

| Line 5 | Port used with C2 Server #1 | 443 | 443 |

| Line 6 | Port used with C2 Server #2 | 443 | 443 |

| Line 7 | Port used with C2 Server #3 | 443 | 443 |

| Line 8 | Password for operator login | tibetwoman | tibetwoman |

| Line 9 | Campaign ID, transmitted to C2 during login | NNNN | NNNN |

Table 1: Decoded configuration parameters from both KeyBoy samples observed in the Parliamentarian operation

A full description of the new algorithm used by KeyBoy to decode its configuration file is presented in Appendix A.

Once the KeyBoy DLL has been executed, it validates that a particular string value (likely identifying the KeyBoy version) is set in the Windows Registry.

| Key | First sample | Second sample |

| HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Zonemap\Ver | 20160509 | agewkassif |

Additionally, these versions of KeyBoy ensure persistence by setting the wab32res.exe file to be loaded upon login via exploiting the Winlogon Shell key, which in turn loads the malicious wab32res.dll file by the aforementioned DLL search-order hijacking method.

| Key | Value |

| HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\Shell | explorer.exe, “C:\users\<user>\AppData\Local\wab32res.exe” |

The backdoor then sends a login beacon to the C2 server which, once decoded, looks like:

These values are described as follows in Table 2:

| Value from Example | Description |

| *a* | Data header code for initial check-in beacon |

| USER-PC | %computername% of victim PC |

| 192.168.100.101 | IP address of victim PC |

| NNNN | Campaign ID from the KeyBoy configuration file |

| 2016/09/13 16:11:56 | Timestamp of local PC |

| 20160509 | Internal version identifier |

Table 2: Descriptions of the login beacon values

This login data, as well as all other communication between backdoor and command and control server, is transmitted using an encoding mechanism based on principles from modular arithmetic. We describe this network communication encoding in detail in this supplementary document.

As can be seen in the login event example above, when sending data to the C2, the KeyBoy implant uses a series of header ‘codes’ to specify the type of data which is being transmitted, described in Table 3:

| Header code | Data being transmitted |

| *l* | Heartbeat / Keepalive |

| *a* | Initial check-in beacon |

| *s* | System information (drive info, system specifications, interface info) |

| *d* | Data from remote commands and shell |

| *f* | Data relating to interactions via File Manager |

| *g* | Ready to initiate file download |

| *h* | Ready to initiate file upload or update |

Table 3: KeyBoy header codes for sending data to the C2 server

The Infrastructure

The command and control (C2) servers used in the Tibetan Parliament operation were extracted from the KeyBoy configuration files:

| C2 Host: 45.125.12[.]147 | Desc: Royal Network Technology Co | City: Guangzhou | Country: China |

| No relevant data or passive DNS information was available | |||

| C2 Host: 103.40.102[.]233 | Desc: Dragon Network Int’l Co. Ltd | City: Hong Kong | Country: Hong Kong | ||||||||||||

Domain: tibetvoices[.]com

|

|||||||||||||||

We uncovered very little information about the command and control (C2) infrastructure used in this operation. The configuration files referenced hard-coded IP addresses for the C2 servers, as opposed to using domain names as was seen in prior KeyBoy campaigns.

Passive DNS analysis revealed one domain, tibetvoices[.]com, which was briefly pointed to one of the C2 server IP addresses found in the KeyBoy configuration file used in the first attempt against the Parliamentarians. This domain was created in May 2016 (around the time that the KeyBoy sample used in the first attempt was compiled) and was pointed to IP address 103.40.102[.]233 from July 15 to September 28. Subsequently, this domain was pointed to 127.0.0.1, effectively taking it offline.

This behavioural tactic was previously mentioned in relation to KeyBoy in a 2013 blog post by Cisco. Cisco hypothesized that the actors behind KeyBoy may have been nullifying the DNS records when an active campaign was not underway, in an attempt to stay “below the radar”. This tactic allows the malware operator to ensure that no command and control traffic will be sent out from the infected system, thus preventing detection via network monitoring.

This tactic, however plausible, would not apply to the KeyBoy samples we analyzed, as the C2 configuration relied upon hard coded IP addresses and did not directly reference the tibetvoices[.]com domain. It is possible that a different campaign was launched which used this domain, but we were unable to find any evidence of such a campaign.

Our analysis provides a cursory look at some of the capabilities and implementation details of the KeyBoy backdoor as used during a malware operation targeting Tibetan Parliamentarians. These versions of KeyBoy differed from the one first described by Rapid7 in several ways, many of which will be described in the sections to follow.

During our research into this operation we were able to uncover two additional samples of KeyBoy which were likely used in previous malware campaigns. These samples were contained in exploit documents containing distinct lure content, one having a Tibetan nexus, the other an Indian nexus.

In Part 2 we present a brief overview of the observable evolution of KeyBoy based upon all of the samples we obtained.

Part 2: KeyBoy – Tracking Evolution

Periodic updates are common in the world of software development. Features are added and removed, bugs are patched, and code is written to execute more efficiently. The same holds true for malicious software, but with the additional requirement that the development cycle must always satisfy the operational need for covertness. To be effective, malicious software designed for surveillance must remain undetected. Malware developers are in a constant struggle to avoid the security controls that protect target systems.

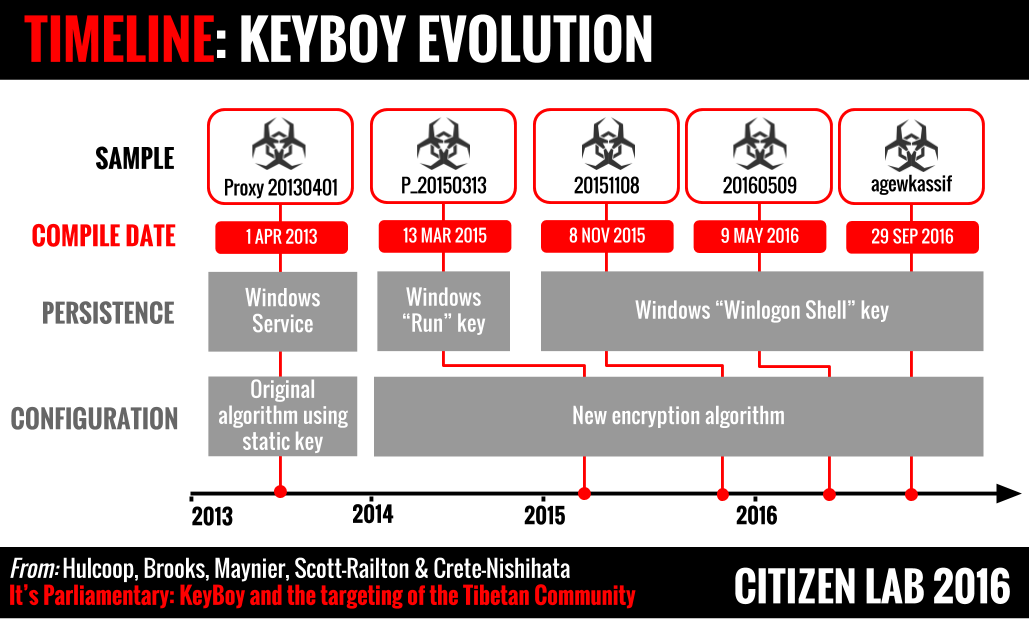

We believe the 2013, 2015, and 2016 KeyBoy samples provide evidence of a development effort focused on changing components that would be used by researchers to develop detection signatures. This section outlines how we came to this conclusion.

In building our KeyBoy chronology, we collected several samples and examined three data points from each:

- The compile time of the KeyBoy binary

- A string observed in the KeyBoy binary we refer to as the ‘version identifier’

- Elapsed time between compile time and the time of first exposure

Analysis of these data points gave us a moderate to high level of confidence that the binary compile times provided a reliable estimate of the true development timeline.

An Evolving Implant

In an effort to understand its evolution, we compared the code of several versions of KeyBoy as identified by their ‘version identifier’ strings, shown in Table 4:

| Version Identifier | Notes |

| Proxy 20130401 | Reported by Rapid7 in relation to an Indian nexus |

| Proxy 20130401 | Reported by Rapid7 in relation to a Vietnamese nexus |

| P_20150313 | Discovered via hunting; carried Indian lure content |

| 20151108 | Discovered via hunting; carried Tibetan lure content |

| 20160509 | First sample of the Parliamentarian operation from August 2016 |

| 20160509 | An alternate sample, using different configuration data |

| agewkassif | Second sample of the Parliamentarian operation from October 2016 |

Table 4: Version identifier strings analyzed

The ‘version identifier’ is a particular string that appeared in every KeyBoy sample we studied. It is transmitted to the command and control server as part of the login data packet, and, in recent versions, this identifier is written to the Windows registry in a key named ‘Ver’. With the exception of the newest (chronologically speaking) KeyBoy version we discovered, this identifier always contained a date-like component which matched the compile date of the KeyBoy binary in every case. In the newest sample, the developers replaced this date-like string with a seemingly random set of letters.

A timeline depicting these KeyBoy versions, along with some important characteristics, is shown in Figure 5.

Noteworthy Modifications

This section describes some of the most significant changes observed across the KeyBoy versions. Each of these components would have been an ideal target for signature-based identification, using either static string or network packet-based detection mechanisms.

Header Code Evolution

Of the changes we identified one stands out as being an immediate target for an effective antivirus signature – the evolution of header codes used during communication between the implant and command and control server. As shown in Table 5, these codes changed substantially after the 2013 KeyBoy samples were examined and publically documented by Rapid7. It is reasonable to hypothesize that this significant change in format was in response to the publication of Rapid7’s research.

| 2013 | Early 2015 | Late 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|

| $login$ | #l# | *a* | *l* |

| $sysinfo$ | #s# | *s* | *a* |

| $shell$ | #e# | *d* | *s* |

| $fileManager$ | #f# | *f* | *d* |

| $fileDownload$ | #D# | *g* | *f* |

| $fileUpload$ | #U# | *h* | *g* |

| *h* |

Table 5: Header codes used by KeyBoy during C2 communication

In addition, modifying these codes produced a downstream change in the appearance of the network communication traffic produced by an active KeyBoy infection. This change would likely have rendered existing network based signatures ineffective.

Configuration File Changes

Another major change we first observed in version P_20150313 is the complete redesign of the algorithm used to encode the KeyBoy configuration file. In the 2013 samples described by Rapid7, this configuration file was encoded using a simplified static-key based algorithm. This newer encoding algorithm is significantly more involved, removing the use of a static encryption key in favour of a dynamically constructed lookup table. We provide a detailed explanation of this new algorithm in Appendix A.

Persistence Changes

The method used by the implant for maintaining persistence was also changed several times. The earlier versions used a Windows service to ensure the malware stayed persistent, moving to a more commonly seen tactic of setting the Run key in the Windows registry in the early 2015 sample. This method changed again in late 2015 when the implant migrated from the Run key to using a less frequently observed registry key: Winlogon\Shell. This key stores the list of executables which are to be run once a Windows GUI session is created, and typically holds only the standard user shell, explorer.exe.

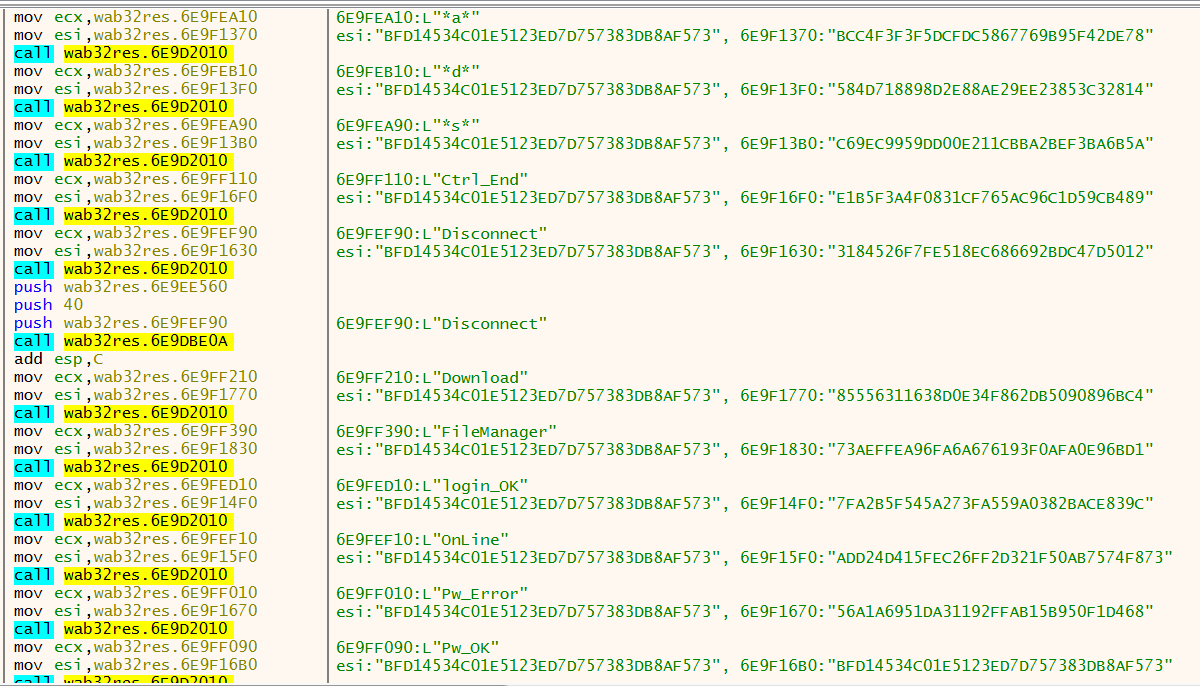

String Obfuscation

In another modification, first observed in the most recent October 11 Parliamentarian operation (version agewkassif), the developer(s) of KeyBoy began using a string obfuscation routine in order to hide many of the critical values referenced within the malware. This introduction of string obfuscation also suggests a development change aimed at evading detection. The header codes, filename references, and all of the operator commands were obfuscated and only decoded during execution of the KeyBoy DLL. Figure 6 shows a sampling of these strings, after decoding.

Evidence of Modularity

Finally, there were numerous changes observed that could suggest that KeyBoy was being deployed using a modular or component based mechanism. The GetUp export which is linked to the browser credential theft capability seems to be present in some samples and not others, even for versions within the same development stage. As well, the inconsistent use of a dropper binary during infection is further evidence supporting the modular component theory.

Additional Details

Beyond the main modifications outlined above, numerous smaller changes were also observed, many of which are described in Table 6 below.

| Version Identifier | Key Changes |

| Proxy 20130401 |

|

| P_20150313 |

|

| 20151108 |

|

| 20160509 |

|

| agewkassif |

|

Table 6: Changes observed between successive versions of KeyBoy

Additional technical details relating to several of the KeyBoy samples described in this section are provided in Appendix B.

Connecting KeyBoy to Other Operations

In their Operation Tropic Trooper report, Trend Micro documented the behaviour and functionality of an espionage toolkit with several design similarities to those observed in the various components of KeyBoy. Trend Micro specifically noted that the 2013 versions of KeyBoy used the same algorithm for encoding their configuration files as was observed in the Operation Tropic Trooper malware.

This connection may offer another explanation for the significant change in the configuration file encoding algorithm we described in relation to KeyBoy. If KeyBoy is a single component of a larger espionage toolkit, the developers may have realized that this older, static-key based, configuration encoding algorithm was inadvertently providing a link between disparate components of their malware suite.

A Note on Samples

We were not able to locate a large sample set for KeyBoy. Though we discussed the development timeline, we have limited insight into the victims targeted by each of these samples. We cannot conclude that all are being deployed by the same group. We provide YARA signatures and encourage anyone who can provide additional samples or context to contact us.

Recent Tibetan Protests

The harm of malware operations against the Tibetan community is well-documented, and this latest campaign is no exception. Examining the lure content sent to the Tibetan Parliamentarians sheds light on the oppression faced by the Tibetan community. On October 19, over 180 Tibetan groups protested the ongoing demolitions of the Larung Gar Buddhist Academy, the largest Tibetan Buddhist institute in the world.

The demolitions stem from an order issued by Chinese authorities in June 2016, according to a joint statement issued by Tibet groups on the date of protest. According to the same joint statement, the order from Chinese authorities said the community was in need of “ideological guidance” from the Chinese state. In conjunction with the demolitions, residents are being forcefully removed from Larung Gar. To date, the forced removals have led to to the suicide of three resident nuns.

The Communist Party of China views the Tibetan movement as a threat to its rule, alongside Uyghur, Falun Gong, advocates for an independent Taiwan and Hong Kong, and members of the democracy movement. Surveilling the highest governing body of the Central Tibetan Administration aligns with the overall interests of the government of China. However, connecting the malware development ecosystem and the flow of stolen information to a state-actor is an elusive task. With the data available we are unable to conclusively connect the Parliamentarian Operation to any specific actor or nation-state.

Conclusions

Recent Citizen Lab reports have documented a trend away from the use of attachment-based malware operations targeting the Tibetan Diaspora. These changes may reflect malware operators shifting tactics in response to changes in the community, including education campaigns encouraging Tibetans not to use email attachments, or perhaps also by more sophisticated attachment scanning by popular email providers.

The operation against the Tibetan Parliamentarians illustrates the continued use of malicious attachments in the form of documents bearing exploits. These exploits, while older, were used to deliver a malware payload which shows signs of a systematic technical adaptation designed to reduce the likelihood of signature based detection.

The developers of KeyBoy have made the minimum necessary technical changes required to avoid detection by signature-based antivirus, and yet retained “old” exploits because they likely continue to work their targets.

For a community lacking an adequate level of human and financial resources, deployment of commercial (i.e.: non-free) antivirus solutions, updated releases of common office productivity software, and even software patches may be out of reach. Under such conditions, the use of exploits against older, patched, vulnerabilities becomes yet another iteration of an actor using “just enough” sophistication to successfully exploit a target.

The operation against the Parliamentarians yields a clear example of this tactic. When the August operation failed to fully compromise the target group, the operators redeployed in October using a slightly newer, but still well-known and patched, exploit.

As we observe the evolution of strategies levied against the Tibetan Diaspora, the constant cat-and-mouse game embroiling this community becomes evident. While some behavioural adaptations have shown promise in reducing the threat, the operation against the Tibetan Parliament underscores the need for continued diligence and security awareness.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Tibet Action Institute. Additional thanks to Jakub Dalek, PassiveTotal, VirusTotal, and TNG.

Appendix A: Decoding KeyBoy Config

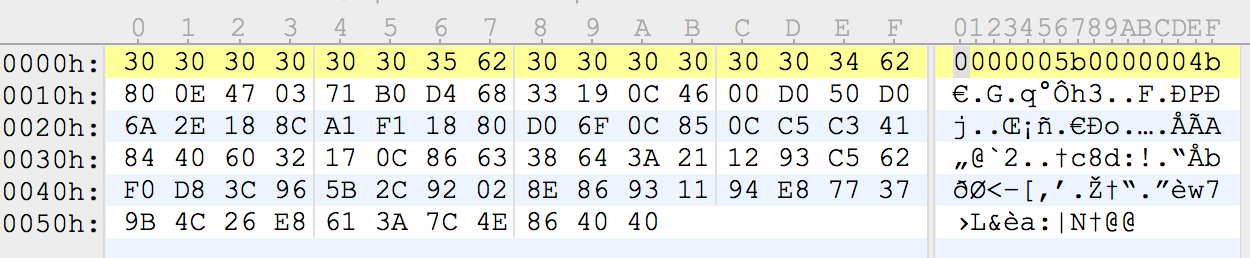

Recent versions of KeyBoy maintain encoded configuration data inside a file stored on disk. In the 20160509 sample used in the Tibetan Parliament campaign, this file was named wab32res.dat. The configuration file contains a 16 byte header followed by a number of bytes which are encoded using a novel algorithm. The 16 byte header stores an ascii character representation of the hexadecimal values corresponding to the size (in bytes) of the decoded config data, followed by the number of bytes containing encoded configuration data.

The sample under examination contained the following header, and Figure 7 shows the raw configuration file:

| Size of config (in bytes) once decoded | Number of bytes in encoded config | ||||||||

|

|

The configuration file used by this malware is encoded using what appears to be a custom schema. While some earlier versions of this backdoor used more simplified encoding techniques for the configuration data, newer versions have adopted a more involved algorithm.

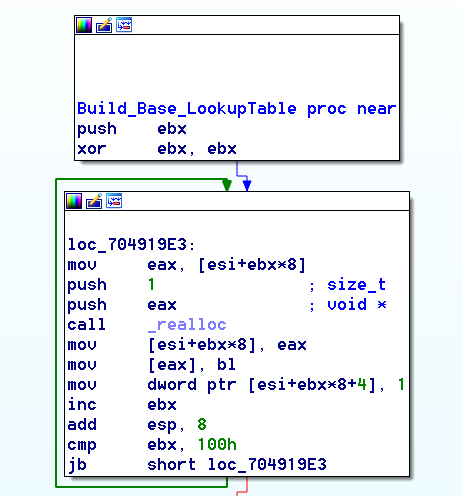

At the heart of the decoding function is the use of a dynamically constructed lookup table containing sequences of bytes which represent the ASCII characters for the cleartext configuration data.

At the outset of the decoding function, a base lookup table is created containing 256 entries. This initial table can be thought of as an identity matrix, where, for each index, the lookup table contains the index as the stored value (see: Figure 8). For example:

| LookupTable[0x0] | → | 0x0 |

| LookupTable[0x1] | → | 0x1 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | |

| LookupTable[0xFF] | → | 0xFF |

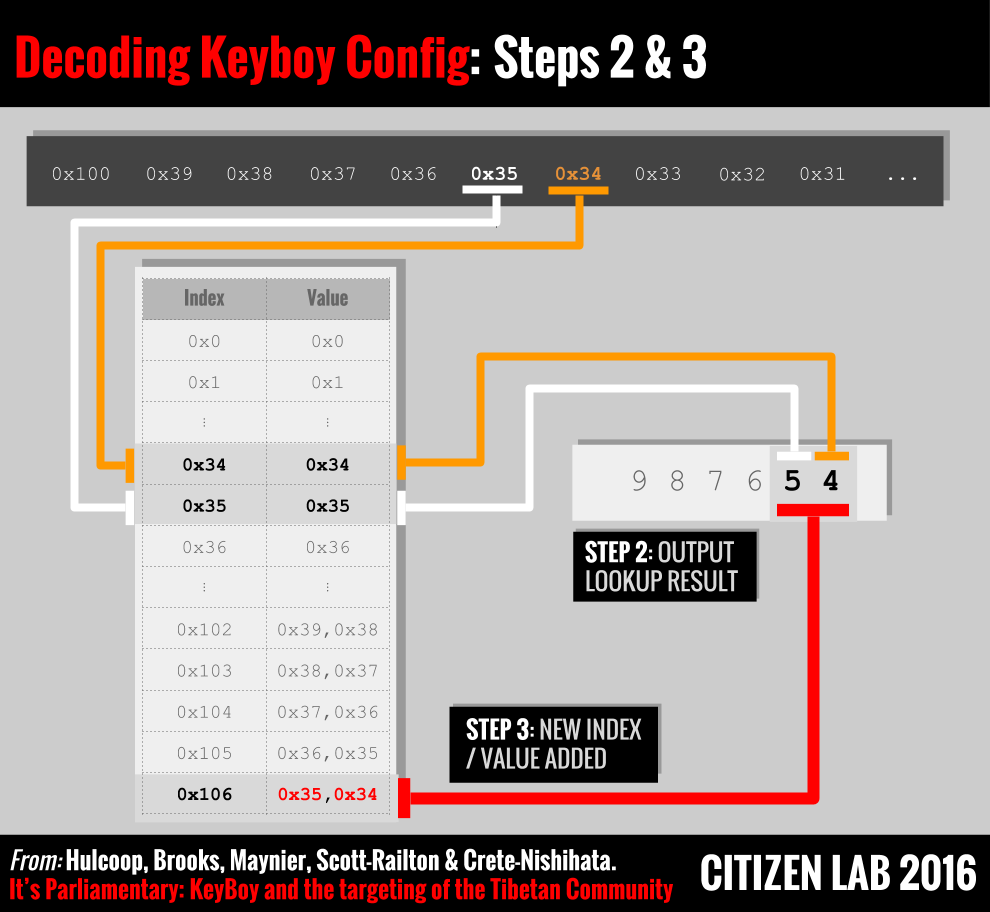

During the decoding of the configuration file, this table is expanded dynamically. Each iteration of the algorithm will populate the lookup table sequentially, beginning with index 0x102 (since the table index 0x101 is reserved).

Algorithm Walkthrough

The algorithm has three basic steps:

- Obtain an index by decoding a value from the configuration file

- Find the value in the lookup table corresponding to this index, and place this result in the memory buffer holding decoded configuration data

- Generate a new value and insert it into the lookup table at the next available index

Step 1

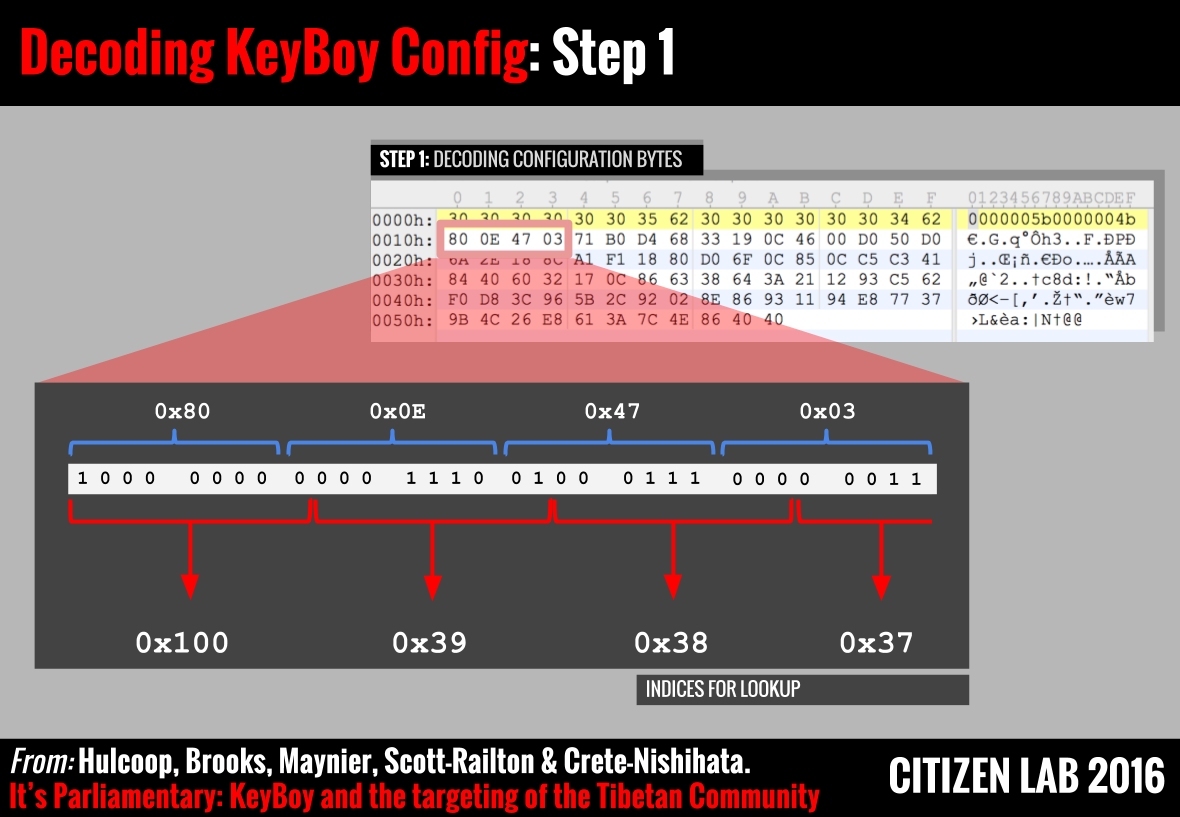

This step requires the algorithm to obtain an index value from the configuration file. In order to obtain this index, a decoding function evaluates the data in the configuration file not as successive bytes, but as a series of integers calculated by considering consecutive sequences of 9-bit binary values.

Figure 9 provides a visual representation of this process. We can see that the first few indices being calculated by this decoder are hexadecimal values 0x100, 0x39, 0x38, and 0x37. The first value, 0x100, is a ‘marker’ which denotes the beginning of the configuration data. The values 0x39, 0x38, and 0x37 are the first three indices used to obtain data from the lookup table.

Step 2

As mentioned above, the first 256 entries in the lookup table are created as an identity matrix, and thus the result of lookups for 0x39,0x38,0x37 would be:

These values are then stored in memory as decoded bytes of configuration data.

Step 3

After each iteration of calculating an index (step 1) and then obtaining the corresponding value from the lookup table (step 2), the algorithm will create a new entry in the lookup table at the next available index. The format of this new lookup table entry is simply the concatenation of the results of the previous lookup with the first byte of the current lookup (see: Figure 10).

So, again using the same example bytes along with Figures 9 and 10 above, if the current iteration of the algorithm decoded the value 0x34 in step 1, and thus retrieved the value 0x34 = ‘4’ in step 2, the newly formed lookup table entry would be:

Thus, if at some future point in the decoding process the index 0x106 was obtained in step 1, the output to the configuration data would be the two bytes [0x35,0x34] which have ascii representation “54”. This provides a method of data compression to the configuration file.

A Python script was created for the purpose of automating this configuration file decoding process. The output of this script when run against the configuration file used by the first of the two Parliamentarian operation samples yielded the following data:

Appendix B: KeyBoy Samples

Version: P_20150313

Installation

This sample was discovered inside a malicious PowerPoint slide show which carried lure content consistent with an Indian-nexus, and which was uploaded to VirusTotal in April 2015 using the filename athirappalli.pps. Athirappilly is a village in India known for its wildlife and waterfalls. The visual contents of the slide show are images of waterfalls, presumably from this village. This malicious .pps file was weaponized using (closely related to CVE-2014-4114 aka Sandworm, which we have previously observed this exploit used against the Tibetan community) to execute the following embedded DLL:

Persistence

This DLL maintains persistence by setting the following registry entry in the HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run key: SystemCertificates → "cmd /c start Run dll32.exe %APPDATA%\Microsoft\SystemCertificates\SystemCertificates.ocx, SSSS

This registry key is set via the Sandworm exploit, as the execution of an .inf file containing the following instructions are triggered:

In comparison with the prior generation of KeyBoy examined by Rapid7, this mechanism represents a change to registry based persistence from the previously used Windows service.

Configuration

Using the algorithm presented in Appendix A, we were able to decode the configuration file used by this sample. Once decoded, the following information was obtained:

Infrastructure

| C2 Host: www.about.jkub[.]com | Desc: Dynamic DNS provided by changeip.com | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| C2 Host: www.eleven.mypop3[.]org | Desc: Dynamic DNS provided by changeip.com | |||||||||

|

||||||||||

| C2 Host: www.backus.myftp[.]name | Desc: Dynamic DNS | ||||||

|

|||||||

Version: 20151108

Installation

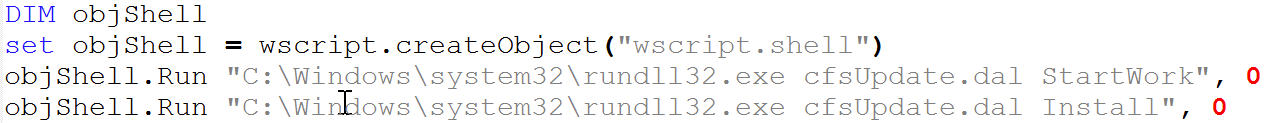

This .rtf document, also exploiting CVE-2012-0158, was submitted to VirusTotal in March 2016. The exploit triggers the execution of an embedded dropper, similar to the method observed in our initial sample described in Part 1.

This dropper creates three files on disk, each in the %localappdata% folder:

- cfs.dat – KeyBoy configuration file

- cfsupdate.dal – KeyBoy payload DLL

- desk.vbs – Windows script used for installation

The Windows script file, desk.vbs, contained the following content:

The dropper executes this script file which subsequently launches the KeyBoy backdoor and sets persistence as described below.

Also noteworthy in this sample was the fact that this payload inspected the architecture of the victim PC to determine if it was 64 bit capable. If so, a 64 bit version of the payload was decoded from the data section of the cfsupdate.dat file using an XOR operation having key 0x90. This is very similar to the method described by Trend Micro in their report on the TROJ_YAHOYAH malware.

Interestingly, the 64-bit module was packed using a known freeware binary packer. This is in contrast to the 32-bit versions of KeyBoy, none of which contained any binary protections whatsoever. Upon unpacking, the 64-bit version of this KeyBoy code was functionally identical to the 32-bit version.

Leftover Code

Further illustrating the continued development and connections between samples are the leftover remnants from 20151108 existing in the 20160509 Parliamentarian sample. The Parliamentarian dropper contained references to the Desk.vbs script described above, yet this file and related content was not deployed or otherwise used in the 20160509 version.

Persistence

Persistence is achieved through the WinLogon\Shell registry key, and is installed by the dropper’s execution of the Install export from the KeyBoy DLL. This export creates the file %localappdata%\Desktop.ini as shown below, and installs it by launching the Windows regini.exe command:

Configuration

The configuration file used by this version of KeyBoy is written to disk as %localappdata%\cfs.dat by the dropper, similar to the behaviour of our 20160509 sample. This configuration file uses the newer encoding method outlined above and in Appendix A. Once decoded, the following information was obtained:

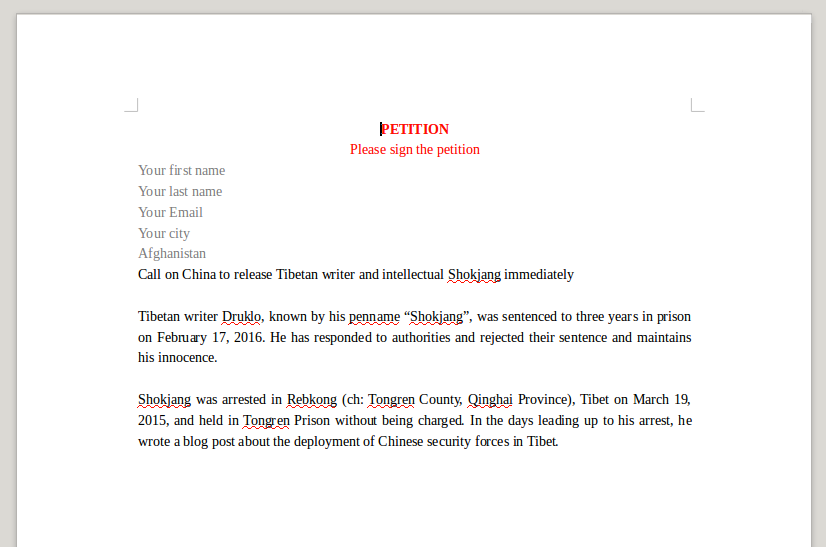

Possible Targeting

This malicious document embedded an empty decoy document to hide the exploitation of the vulnerability. We found however another interesting sample with the exact same payload but with a decoy document presenting a petition to release a Tibetan activist:

Infrastructure

This sample communicates with the following command and control server:

Version: 20160509 (alternate)

During our research we encountered another sample of the 20160509 version of KeyBoy. This sample was also found to be deployed using the CVE-2012-0158 vulnerability. The malware payload was identical to our first Parliamentary sample outlined in Part 1, however the configuration file in this alternate sample was different.

Configuration

Possible Targeting

The exploit document carrying this alternate KeyBoy configuration also used a decoy document which was displayed to the user after the exploit launched. This decoy carries content with a Tibetan nexus.