Nile Phish

Large-Scale Phishing Campaign Targeting Egyptian Civil Society

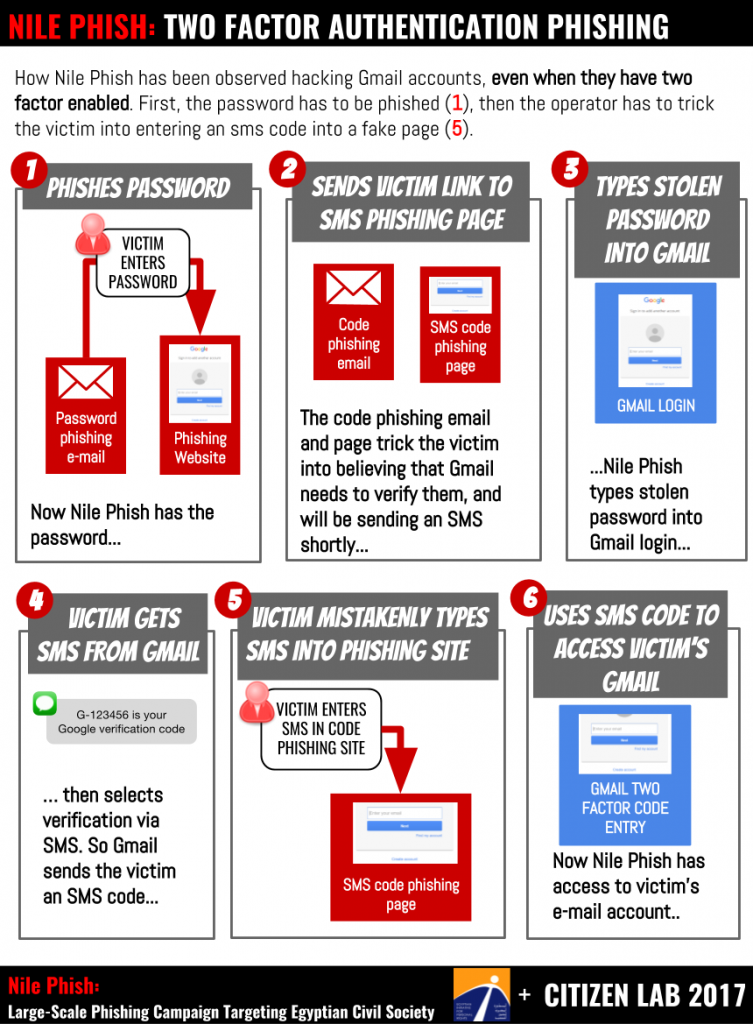

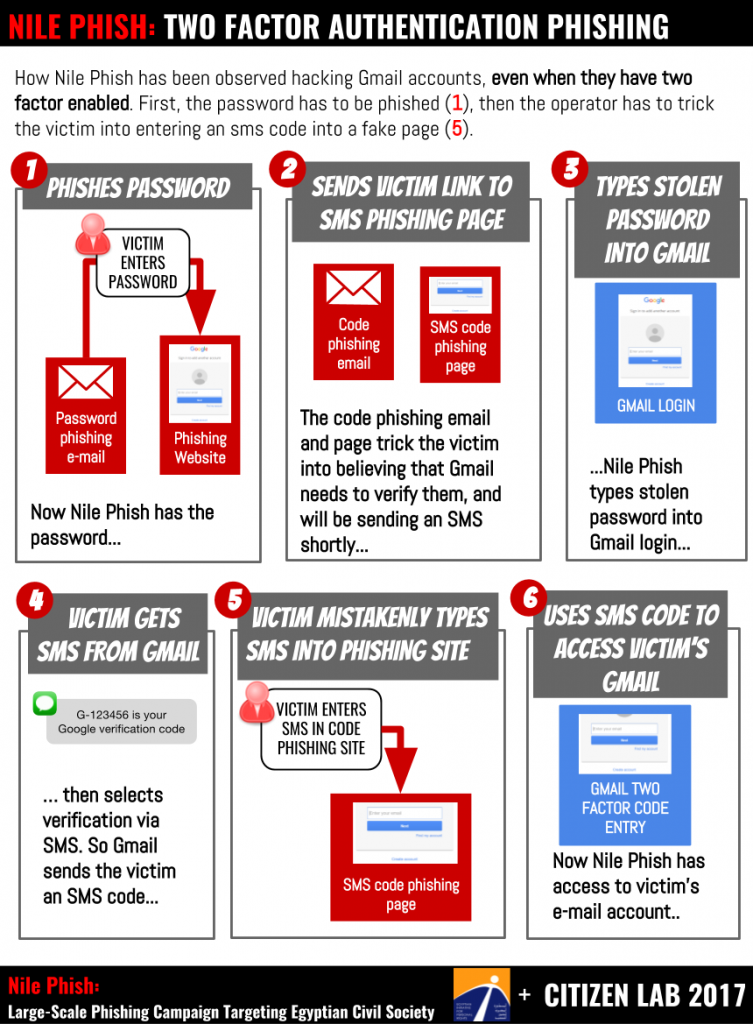

Diagram explaining how Nile Phish operators phish users who have enabled 2 factor authentication. [Click for hi res]

This report discusses the targeting of Egyptian NGOs by Nile Phish, a large-scale phishing campaign. Almost all of the targets we identified are also implicated in Case 173, a sprawling legal case brought by the Egyptian government against NGOs, which has been referred to as an “unprecedented crackdown” on Egypt’s civil society. Nile Phish operators demonstrate an intimate knowledge of Egyptian NGOs, and are able to roll out phishing attacks within hours of government actions, such as arrests.

- Key Findings

- Summary

- Background

- Phase 1: Arrest Warrants, Invitations, and Travel Ban Lists

- Phase 2: A Tactical Shift

- Nile Phish Using Open-Source Phishing Toolkit

- Nile Phish Infrastructure

- Phishing: The Royal Road to Account Compromise

- Conclusion: Nile Phish Is Yet Another Threat to Egypt’s Civil Society

- Appendix A: Indicators of Targeting

Key Findings

- Egyptian NGOs are currently being targeted by Nile Phish, a large-scale phishing campaign.

- Almost all of the targets we identified are also implicated in Case 173, a sprawling legal case brought by the Egyptian government against NGOs, which has been referred to as an “unprecedented crackdown” on Egypt’s civil society.

- Nile Phish operators demonstrate an intimate knowledge of Egyptian NGOs, and are able to roll out phishing attacks within hours of government actions, such as arrests.

UPDATE 2/23/2017

EVIDENCE OF TWO-FACTOR PHISHING

Since publication, the Citizen Lab and EIPR have been contacted by a number of additional targets. We are preparing a follow-up report, but we believe it is important to note that there is now evidence that the Nile Phish operator has engaged in phishing of 2-factor authentication codes.

See: Evidence of 2 Factor Phishing

Summary

This report describes Nile Phish, an ongoing and extensive phishing campaign against Egyptian civil society. In recent years, Egypt has witnessed what is widely described as an “unprecedented crackdown,” on both civil society and dissent. Amidst this backdrop, in late November 2016 Citizen Lab began investigating phishing attempts on staff at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), an Egyptian organization working on research, advocacy and legal engagement to support basic freedoms and rights.

With the collaboration and assistance of EIPR, our investigation expanded to include seven Egyptian NGOs targeted by Nile Phish. These seven organizations work on a variety of human rights issues, including political freedoms, gender issues, and freedom of speech. We also identified individual targets, including Egyptian lawyers, journalists, and independent activists.

With only a handful of exceptions, Nile Phish targets are implicated in Case 173, a legal case brought against NGOs by the Egyptian government over issues of foreign funding. The phishing campaign also coincides with renewed pressure on these organizations and their staff by the Egyptian government, in the context of Case 173, including asset freezes, travel bans, forced closures, and arrests.

Our collaborative investigation has documented at least 92 messages sent by Nile Phish, many highly personalized, and sent as recently as January 31st, 2017. The phishing campaign has included at least two phases, each with distinct phishing tactics and domains. Efforts seem to have been made to compartmentalize the infrastructure for each phase, but a technical error allowed us to link the servers and conclude that the two phases were part of a single campaign.

Nile Phish’s sponsor clearly has a strong interest in the activities of Egyptian NGOs, specifically those charged by the Egyptian government in Case 173. The Nile Phish operator shows intimate familiarity with the targeted NGOs activities, the concerns of their staff, and an ability to quickly phish on the heels of action by the Egyptian government. For example, we observed phishing against the colleagues of prominent Egyptian lawyer Azza Soliman, within hours of her arrest in December 2016. The phishing claimed to be a copy of her arrest warrant.

We are not in a position in this report to conclusively attribute Nile Phish to a particular sponsor. However, the scale of the campaign and its persistence, within the context of other legal pressures and harassment, compound the extremely difficult situation faced by NGOs in Egypt.

Background

In recent years, political assembly, freedom of speech, independent media, and civic organizing have been increasingly constrained in Egypt. This concerted effort has been widely called an “unprecedented crackdown” against civil society. One component of this effort has been a rising tide of official and semi-official allegations of foreign interference and foreign funding against Egypt’s civil society organizations.

In 2011, the Egyptian Government embarked on a wide-ranging legal case charging that many civil society organizations receive foreign funding, and may be engaged in prohibited or illegal activities. The case is widely viewed as politically-motivated, and an attempt to frustrate and block the ability of Egyptian civil society to continue its pro-democracy and human rights monitoring work.

As part of Case 173, international organizations (e.g.,the National Democratic Institute) and domestic groups (e.g. the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights) have been subjected to a wide range of legal sanctions, including arrests, travel bans, asset freezes and harsh sentencing. In 2013, 43 defendants working for international NGOs were sentenced to prison for their work, many in absentia as they had already left the country.

Now more than 5 years old, Case 173 has been marked by periods of calm, and of intense activity. Initially primarily focused on international NGOs like the National Democratic Institute and the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the case has grown increasingly focused on domestic Egyptian organizations. The 37 organizations known to be accused in the case include respected civil liberties groups, pro-bono law firms, and organizations working on gender issues. More recently, beginning in Spring 2016, travel bans and asset freezes were placed on staff members of some domestic organizations under investigation.

As a result, many who work for NGOs named in the case are concerned that their ability to travel may be restricted, and that they may face arrest, jail time or other forms of punishment. Nile Phish, the campaign described in this report, not only targets these individuals, but uses deceptions that play directly into these fears and concerns.

The Nile Phish Campaign

In late 2016, Citizen Lab was contacted by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), whose technical team had observed a growing number of suspicious emails sent to EIPR accounts. The messages had caught the attention of the technical team because multiple messages arrived at the same time, concerned current events, and seemed to play on emotional themes related to Case 173. EIPR’s team helped broaden the investigation to a total of seven targeted Egyptian NGOs.

All of the seven Egyptian organizations are also implicated by Case 173. The targets include reputable and respected organizations working on political and rights issues such as freedom of expression, gender rights, and victims of torture and forced disappearances. Six of the organizations have agreed to be named in this report and one requested to be referenced anonymously (see Table 1).

| Targeted NGO | What They Do |

|---|---|

| Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression (AFTE) | Legal aid, strategic litigation, and awareness-raising on issues of freedom of expression in Egypt. |

| Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) | A regional NGO that promotes respect for human rights and democracy in the Arab Region. |

| Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms (ECRF) | Egyptian organization defending human rights and tracking violations. Tracks and campaigns against forced disappearances |

| Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR) | Works to strengthen and protect basic rights and freedoms in Egypt through research, advocacy, and litigation. Areas of work include civil liberties, economic and social rights, and criminal justice. |

| Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence (Nadeem) | An anti-torture organization that focuses on assisting victims of torture with rehabilitation, including providing legal services and social support. |

| Nazra for Feminist Studies (Nazra) | Promoting the political participation of women, as well as addressing sexual violence, the organization treats feminism and gender rights as political and social issues. |

| Unnamed NGO | This organization has requested that it not be named |

Egyptian NGOs Known to be Targeted by Nile Phish

In addition to the organizations, we identified a small number of individual targets in Egypt, including well-respected lawyers, journalists, and activists.

We strongly suspect that there may be other targets, and hope that the Indicators of Targeting that we provide in Appendix A can be used by systems administrators and others to seek evidence of targeting.

How The Investigation Began

The first Nile Phish message that we examined, sent by Nile Phish to several Egyptian NGOs on November 24, 2016, was made to appear to come from the Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence (Nadeem), and invited the NGO staff member to participate in a nonexistent panel discussing Egypt’s draft NGO Act, which was nearing a vote in Parliament. The recipient was invited to visit a link to read more about the panel.

The operators used language from a real NGO statement that had been circulating, embellishing it with the fake meeting. According to the carefully crafted fiction, the event was co-sponsored by several other NGOs, including EIPR, the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies (CIHRS) and Nazra for Feminist Studies (Nazra). These NGOs were signatories of the legitimate statement. Interestingly Nadeem, EIPR, CIHRS, and Nazra were all later targeted by the same phishing campaign.

Nov 24 Message Excerpt (Translated)“…The state has already taken real steps to eliminate Egyptian civil society organizations by prosecuting case no. 173/2011 on foreign funding, and several organizations and their current and former directors have been banned from travel and have had their assets frozen. This new law, however, would pave the way for the eradication of any sort of civic action geared to development, charitable activities, and services..

…Therefore, El Nadeem will organize jointly with political parties and ngos a panel to discuss the status of the civil society organizations in Egypt in the light of the new act beside the restrictions practiced by the security authorities such as travel ban and assesses free, and others restrictive to societal and development work in Egypt.

[Link to the agenda and to register for the event]

The link led to a site designed to trick the target into believing that they needed to enter their password to view the file. After confirming that the message was a phishing attack, we began investigation in close collaboration with EIPR’s technical team, which was by then observing a second wave of messages claiming to share a document that listed individuals subject to travel bans. The recipients were the staff of Egyptian civil society organizations, many of whom suspected that they might be included on these lists.

We have now documented at least 92 messages from Nile Phish, which we link together by use of the same servers and phishing toolkit. The majority of the emails were sent to the work accounts of the targets. The messages have targeted at least seven organizations, as well as a number of individual activists, lawyers, and journalists. Almost all of the targets are staff of organizations that are defendants in Case 173.

The campaign falls into two phases, which map both onto phishing style, and to different server infrastructure (See: Nile Phish Infrastructure).

What is Phishing?

Phishing is a tactic to steal personal information, like passwords, through deception. Many phishing emails often try to trick you into entering passwords and other secret codes into websites that look legitimate, but are really fake.

While phishing can be used by criminal gangs to steal bank information and for other financial crimes, phishing is also used for espionage and surveillance. For example, the Nile Phish operation seems to be designed to gain access to email accounts and document sharing files belonging to NGOs.

Phase 1: Arrest Warrants, Invitations, and Travel Ban Lists

Late November- Late December 2016

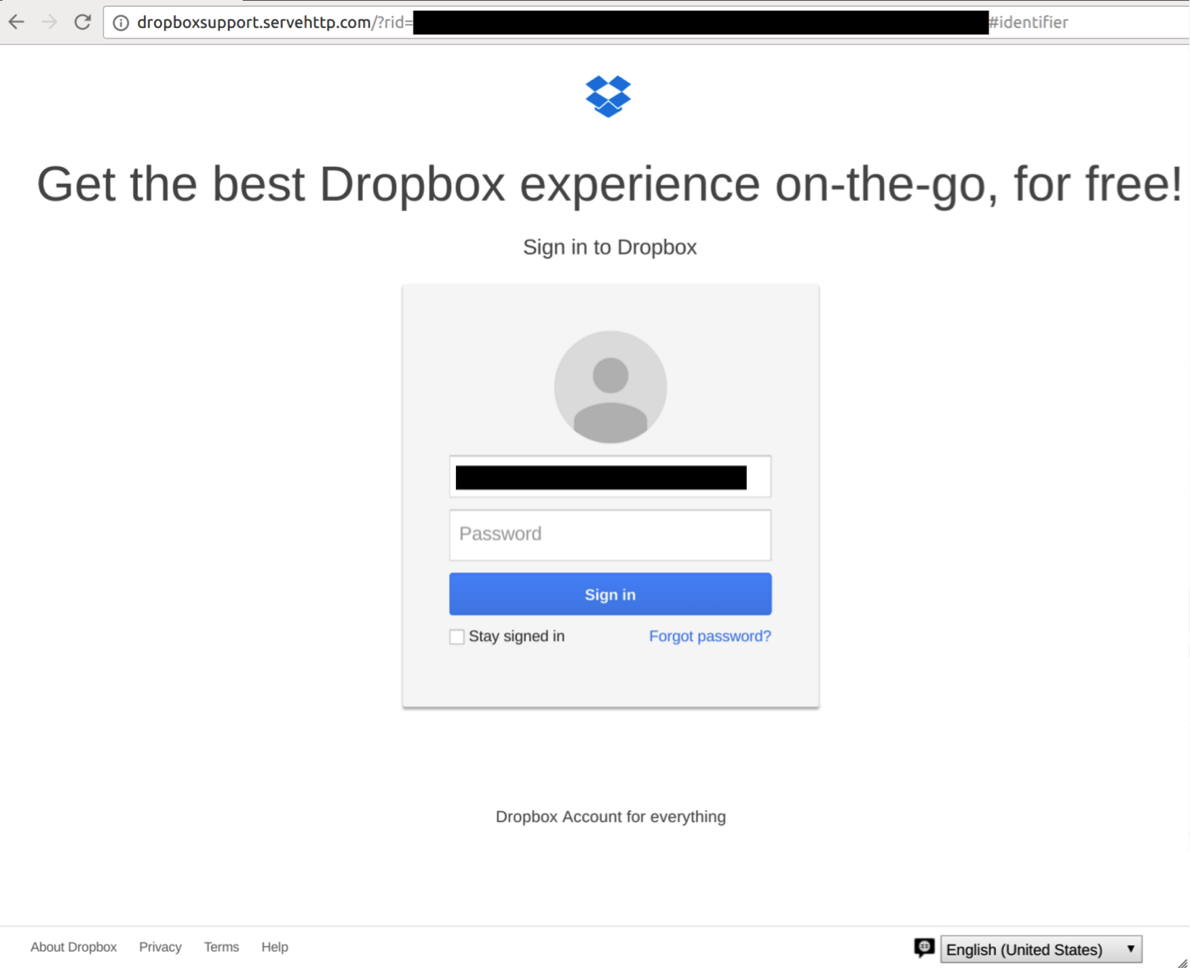

In the first phase of the phishing (approximately November 24-December 26, 2016) a majority of the messages were crafted with references to the ongoing crackdown on civil society, and especially Case 173. Typically, the messages masqueraded as document shares, primarily via Google or Dropbox, containing highly relevant or sensitive information.

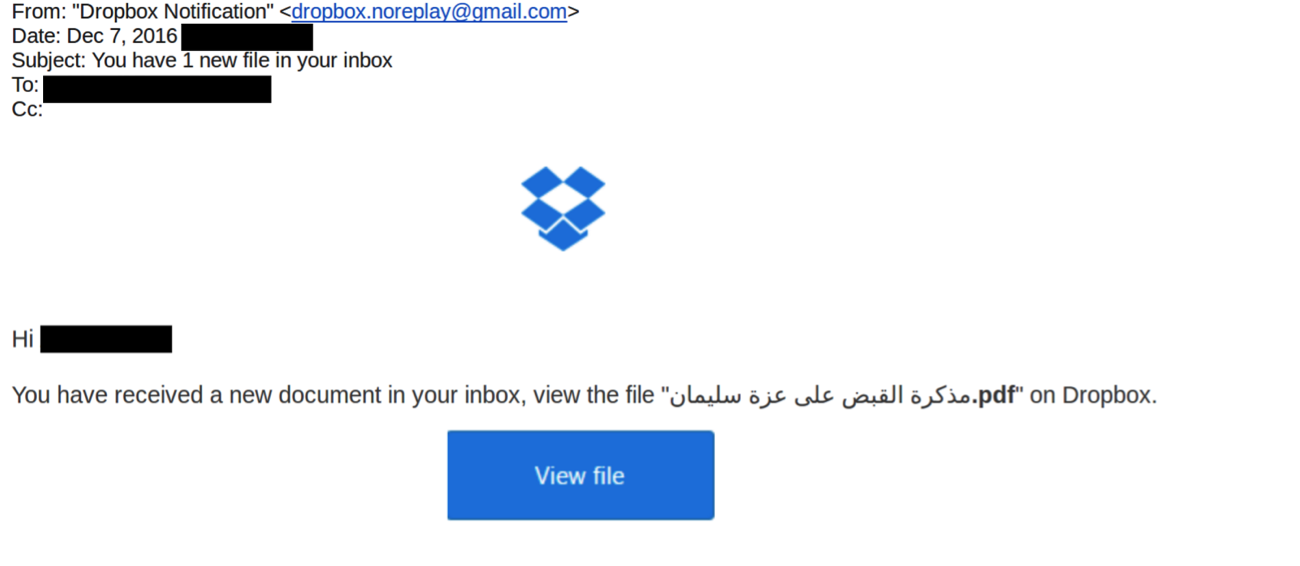

The following example of a phishing email that leveraged a recent arrest of a prominent Egyptian lawyer as a lure, illustrates that the phishing was both extremely timely, and conducted by those well aware of the activities of the Egyptian government. Specifically, it suggests that within a few hours of an arrest, the operator of the campaign was using this event as part of their phishing attack.

An Arrest Becomes Phishing

On December 7, 2016 prominent Egyptian lawyer and the Director of the Center for Women’s Legal Assistance Azza Soliman was arrested at her home. Within hours, while Soliman was still being interrogated at the police station, several of her colleagues in other NGOs received an email purporting to be a Dropbox share of her arrest warrant. (See: Figure 1).

Clicking on the link leads to a Dropbox credential phishing page pre-populated with the target’s username.

A majority of the Phase 1 messages concerned the court case, and were typically sent to targets’ organizational emails. Where targets were independent activists, we also found targeting of their personal email accounts.

| Theme | Pretext | Some Targeted NGOs | Example Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial related | Share of travel ban list | EIPR | dropboxsupport.servehttp[.]com |

| Trial related | Arrest warrant of an activist arrested on the same day | Nadeem | dropbox-service.serveftp[.]com, googledriver-sign.ddns[.]net |

| Trial related | Panel invitation to discuss the case | [unnamed group] | mailgooglesign.servehttp[.]com |

| Trial related | NGO letter to the Egyptian President about the case | CIHRS | dropbox-sign.servehttp[.]com |

Example Domains from Phase 1 Phishing

A majority of the messages were sent using Gmail accounts with names that look like legitimate services. This approach does not hold up to close scrutiny of the sender’s email addresses, but also allows the message to be sent via a sender known to Gmail, and thus not flagged by Gmail as sent over an insecure connection.

| Masquerading As | Lookalike Email |

|---|---|

| Dropbox | Gmail |

| [email protected], [email protected],[email protected], [email protected] | [email protected],[email protected] (Phase 2) |

Phase 2: A Tactical Shift

Mid-December – January 31st 2016 (ongoing)

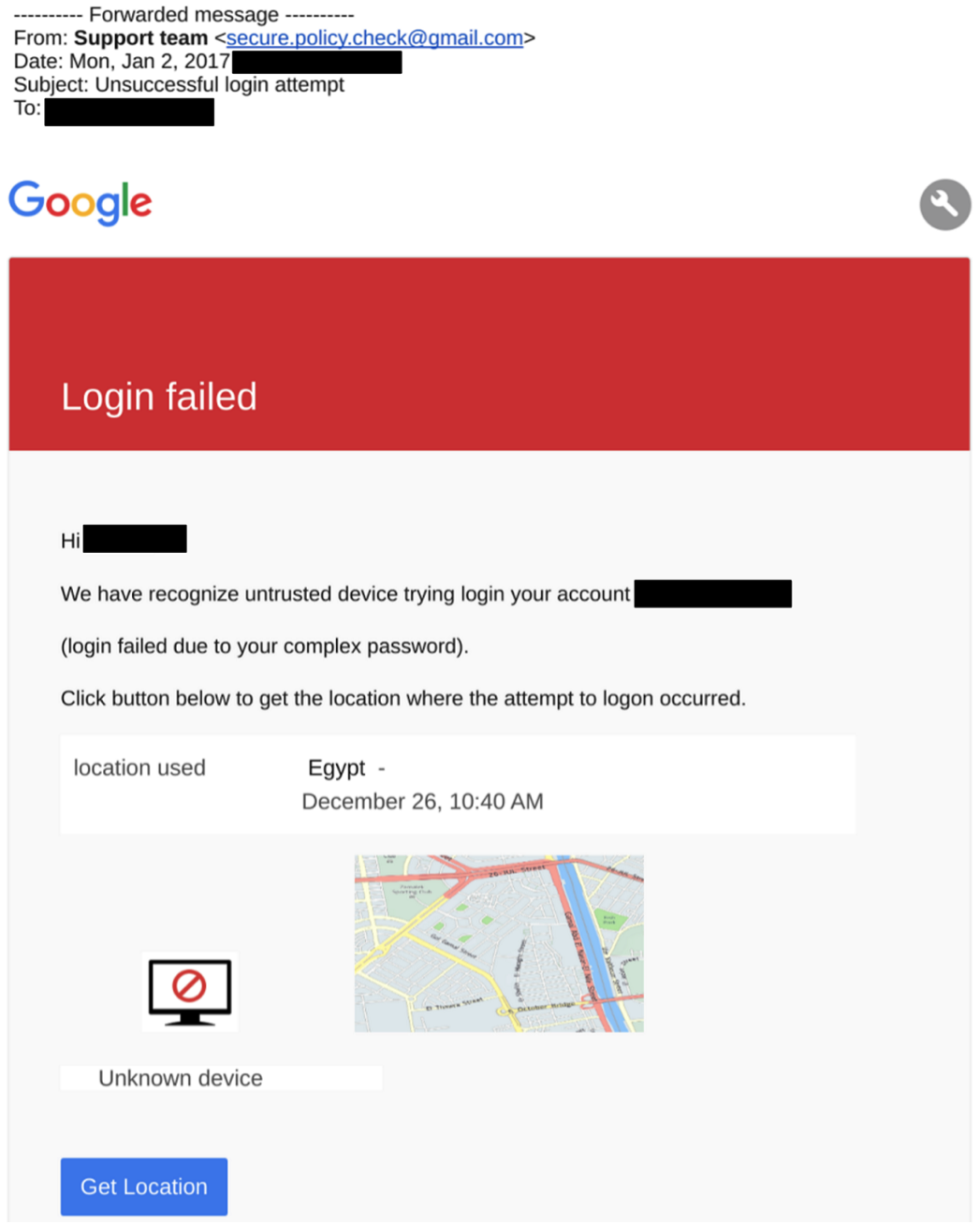

When we began systematically tracking the campaign in late November 2016 almost all of the messages we observed concerned issues related to Case 173, as well as being personalized to the recipient. This approach continued until late December. However, by mid-December, we began observing a growing number of generic phishing messages, mostly emphasizing account security issues.

Here is an example of such a “generic,” but still personalized message.

These messages, while still personalized with users’ names, relied on a range of common phishing tactics, such as warnings of suspicious login attempts, and other account security issues. In a few cases, the operators also included package-delivery notifications. After December 26, we no longer observed any personalized messages. This shift maps onto changes in server infrastructure (see: Nile Phish Infrastructure).

| Theme | Pretext | Some Targeted NGOs | Example Domains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gmail Phishing | Failed login, insecure connection, | EIPR, AFTE, CIHRS, Nazra, ECRF, a prominent journalist | googleverify-signin.servehttp[.]com, googlesignin.servehttp[.]com, security-myaccount.servehttp[.]com |

It is unclear why Nile Phish operators wound-down their use of Case 173 themes as the campaign went on. It is possible, for example, that they began to suspect that the targets were wary of such messages. It is equally possible that they simply decided to scale back some of their efforts, and rely more heavily on the pre-built examples in the toolkit they used. It is also possible that this represents a fluke either in how the messages were collected, or a pause on the part of the operators.

The final possibility is that Nile Phish is a component of a larger operation, and that the operators may intend to continue to use tailored social engineering for other purposes, such as delivering malware.

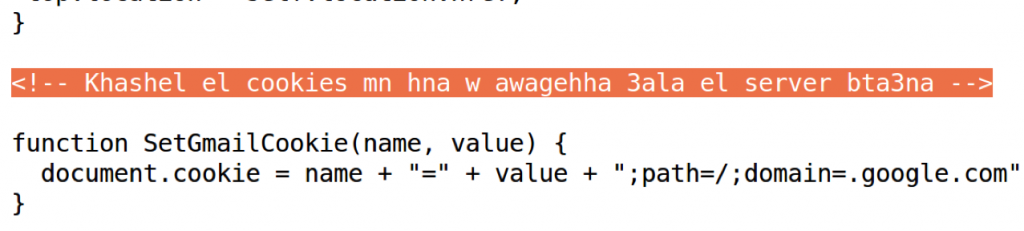

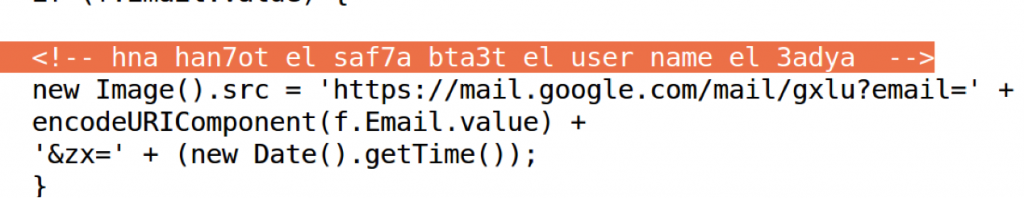

Artefacts: Egyptian Chat Slang

While examining the credential landing pages we also found messages and comments that the Nile Phish operators had left for each other. The writing is instantly recognizable as a form of Egyptian Arabic slang (mixing letters and characters) sometimes referred as Araby.

Nile Phish Using Open-Source Phishing Toolkit

Nile Phish mounted this campaign with gophish, an open-source phishing framework written in the Go language.

The gophish framework is intended to be used defensively, as part of anti-phishing trainings. This is the first offensive use of gophish of which we are aware. Its developer describes it as “designed for businesses and penetration testers. It provides the ability to quickly and easily setup and execute phishing engagements and security awareness training.” Support for capturing credentials submitted on phishing pages was added to gophish in February 2016.

The growing number of open-source and widely available phishing frameworks designed for penetration testing have made it easy to set up a phishing campaign. While some free and hosted phishing frameworks require a degree of authentication onto a particular domain, such as the online Duo Insight, many that are self-hosted do not. The lack of authentication, while minimizing invasiveness and protecting user privacy, is also a double-edged sword, and means that it can be abused to conduct non-consensual and illegal phishing campaigns.

Discovery and Identification

Examination of the phishing infrastructure provided evidence of artefacts from a cloned git repository, suggesting that this was a likely from a project on Github. This led us to conclude that the operators were likely making use of an existing phishing framework. Further investigation revealed that the domains were serving the gophish admin page on port 7777, and the scheme of the phishing URLs matched those of gophish.

Gophish links have a common format, which can be used to quickly identify a link sent via the platform:

http://[domain]/?rid=[target identifier string]

Contact With Gophish

Citizen Lab contacted Jordan Wright, the developer of Gophish and provided examples of the links used in the campaign. Wright provided us the following response:

“…The links have the same structure as those sent in a Gophish campaign and there are Gophish administrative portals available on those hosts.

Gophish is designed to help administrators test their organization’s exposure to phishing. By running phishing tests against one’s own organization, the hope is that members of the organization will be better at spotting and avoiding phishing emails in the future, mitigating attacks like this.

The Gophish team does not condone using the software for any purpose other than running controlled tests to measure your own organization’s exposure to phishing. While we cannot control users and prevent all misuse of the software, we will continue taking any measures possible to prevent this kind of abuse in the future.”

Nile Phish Infrastructure

The campaign’s operators used commercial web hosting located in Europe (Choopa and AlexHost) to host the campaign. They have shown evidence of basic operational security practices, including server compartmentation between Phase 1 and Phase 2. Nevertheless, in what appears to have been a mistake, one domain resolved to servers from both phases at different times.

Using passive DNS analysis tools including PassiveTotal, we were able to further characterize the infrastructure, and how it was used throughout Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the campaign. We also identified an additional 13 domains through passive DNS research, indicating that the campaign may include a range of other targets not uncovered in our investigation.

Phase 1 Infrastructure

Using passive DNS we found that Phase 1 included at least six domains, all hosted on 108.61.176[.]96.

googledrive-sign.servehttp[.]com

dropboxsupport.servehttp[.]com

googledriver-sign.ddns[.]net

dropbox-service.serveftp[.]com

dropbox-sign.servehttp[.]com

mailgooglesign.servehttp[.]com

Phase 2 Infrastructure

The second phase of the campaign included at least 16 domains, hosted on IPs 104.238.191[.]204 and 176.123.26[.]42.

fedex-shipping.servehttp[.]com

verification-acc.servehttp[.]com

google-maps.servehttp[.]com

fedex-mail.servehttp[.]com

secure-team.servehttp[.]com

account-google.serveftp[.]com

googleverify-signin.servehttp[.]com

googlesecure-serv.servehttp[.]com

googlesignin.servehttp[.]com

security-myaccount.servehttp[.]com

myaccount.servehttp[.]com

activate-google.servehttp[.]com

googlemaps.servehttp[.]com

device-activation.servehttp[.]com

aramex-shipping.servehttp[.]com

fedex-sign.servehttp[.]com

Additional Domains

Through passive DNS research, we identified 13 additional domains using the same dynamic DNS server and IP addresses.

dropbox-verfy.servehttp[.]com

fedex-s.servehttp[.]com

watchyoutube.servehttp[.]com

moi-gov.serveftp[.]com

verification-team.servehttp[.]com

securityteam-notify.servehttp[.]com

secure-alert.servehttp[.]com

quota-notification.servehttp[.]com

notification-team.servehttp[.]com

fedex-notification.servehttp[.]com

docs-mails.servehttp[.]com

restricted-videos.servehttp[.]com

dropboxnotification.servehttp[.]com

Linking the Infrastructure

While the operators maintained a degree of compartmentation between domains, we found that the domain fedex-sign.servehttp[.]com resolved to both Phase 1 and Phase 2 infrastructure.

| Domain | Resolution | Until | Infrastructure Belongs to |

|---|---|---|---|

| fedex-sign.servehttp[.]com | 108.61.176[.]96 | 13 December 2017 | Phase 1 |

| 104.238.191[.]204 | 19 December 2017 | Phase 2 |

Phishing: The Royal Road to Account Compromise

Reporting on targeted threats often gets attention because of the sophistication of the attackers’ tools, yet by volume many successful attacks use much less advanced technology. The recent case of an iOS zero day used against UAE and Mexican civil society represents a relatively sophisticated and expensive attack vector. While such an operation is costly and relatively difficult to detect, many operations that we have observed at the Citizen Lab use much less sophisticated technical means.

In this report we described how the Nile Phish operators used targeted, timely, and clever deceptions combined with an open-source phishing framework.

Why Do Many Threat Actors Still Use Credential Phishing?

While we cannot know Nile Phish operators’ reasons for choosing phishing, assuming they have access to other techniques, we can speculate that they used social engineering because it works. A phishing campaign has a number of advantages, even for operators capable of obtaining expensive and sophisticated malware. Indeed, even in cases where the same operators may also possess and deploy malware.

As an exercise, the following table emphasizes some of the advantages of phishing as a technique to gain access to private communications when used by a well resourced actor. The table highlights some of the reasons why such actors may continue to use phishing.

| Concern | Credential Phishing |

|---|---|

| Cost / Skill | Zero or near-zero development cost. Can be deployed with little or no technical skills. |

| Scalability | High. Easily deployed against dozens, thousands, or more targets. |

| Adaptability | High. Domains and emails can be quickly modified if a particular approach is not working. |

| Risk of ‘burning’ expensive tools and methods | Low. Phishing can be conducted using free and open-source toolkits. Discovery does not result in the compromise of special technical tools, costly exploits, or malware |

| Attribution | Debateable. Like the use of Commercial-Off-The-Shelf (COTS) malware, phishing does not instantly point to a particular type of actor, such as a government, as many malicious actors use this technique. Discovery of a tool like NSO Group’s Pegasus or Hacking Team’s Remote Control System, on the other hand, strongly implies state involvement, as they are marketed for lawful intercept purposes and the cost of procuring those tools precludes those without significant resources from acquiring them. Moreover, finding phishing may not alert the target that a sophisticated attacker is present. |

| Diverse target environment | Phishing does not require knowledge of a target’s devices, antivirus, or other endpoint security features. Nor does it require a means to bypass these, such as an exploit, in order to gain access to targeted communications. |

| Gathering relevant data | Email and online accounts often contain huge troves of data which, when compromised, can quickly be siphoned out of accounts remotely. |

Credential Phishing: Why it keeps being used as a surveillance tool

In using phishing, Nile Phish operators are far from alone. Citizen Lab reports have repeatedly pointed out that many operators, including those with access to more sophisticated technologies, persist in phishing and other forms of basic social engineering.

For example, in South America, the Packrat group, which was active against civil society in several countries, made use of credential phishing as part of its multi-year campaign. Similarly, operations targeting the Tibetan diaspora have also made use of phishing, as have operations targeting the Syrian opposition, Iranian pro-democracy organizations, and many others.

Cheap Ways to Make Phishing NGOs Harder

Civil society groups make widespread use of cloud email services, file sharing and collaboration tools. These services are exceptionally helpful to organizations that do not have the resources to maintain or secure self-hosted deployments. Many of these cloud services have powerful security features, like 2-factor authentication, that are capable of blunting the impact of straightforward credential phishing. However, most of these security features are not enabled by default, whether for individual users of cloud services, or for organizations. The absence of default-on security features predictably leads to a lower rate of use, and keeps the door open for phishing.

What is Two Factor Authentication?Two Factor Authentication has many names, like 2 Step Authentication, Login Approvals, 2FA, and so on, but they typically refer to the same thing: combining a password with a second “factor” that only the authorized user has. Most commonly this is a text message sent to the user’s phone. Other versions include physical tokens, code generators, authenticator apps or prompts on devices, and so on.

Click here for a list of services that support Two Factor Authentication.

From the perspective of an NGO however, several approaches are available to increase the cost of phishing, including using more secure forms of 2 Factor Authentication. As a next-level step, organizations can also implement phishing / social engineering awareness exercises.

Increase the Cost to Phish an NGO

| Anti-Phishing Technique | Works on | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| 2 Factor Authentication with Authenticator Apps or Yubikeys | Account security, means that even if credentials are phished a second factor is still required. | 2 Factor Authentication can still be phished in some circumstances, such as tricking victims into entering codes from authenticator apps, although deceptions must be more elaborate. Does not protect against some malware attacks that steal two factor codes from devices. |

| Phishing Training | Human behavior, increasing the likelihood that phishing is noticed. | Can be time consuming, and requires organizational buy-in. While free tools like Duo Insight are available, other solutions can be expensive. |

Using secure 2 factor authentication

The most common form of 2 Factor authentication is to receive SMS messages. Although a growing number of threat actors are experimenting with phishing 2 Factor credentials, and tampering with SMS-based authentication, including in Egypt, when implemented securely the feature is a low-cost way to dramatically increase the cost-to-phish.

One way to increase the security of 2 Factor authentication is to move away from SMS-based authentication to Authenticator Apps or, even more secure, Yubikeys. Both Google and, most recently Facebook, now support Yubikeys for authentication.

Next Level: Behavioural Training

Phishing exploits vulnerabilities that will always be present in human behavior. When a phishing campaign like Nile Phish targets an organization, the operators do not expect that everyone will be duped. One compromise is enough to begin siphoning private data, and to start using that data to construct more convincing phishing or malware attacks against others in an organization.

There is a growing consensus that repeated training with mock-phishing exercises, in the form of realistic phishing e-mails sent by the organization’s IT staff, can be an effective way to build an organization’s ‘human firewall.’ There are a number of free tools that NGOs can use to conduct these exercises, including Duo Insight. Ironically, Gophish is another such tool, although it requires slightly more technical sophistication to implement. Many other solutions are available, many of them commercial. While not every organization will be able to implement behavioral training, it is a free and highly effective strategy for reducing institutional exposure to phishing attacks and social engineering.

What Technology Companies Can Do Right Now

Major online companies have been reluctant to add 2 Factor Authentication as a default for new account creation. Keeping 2 Factor an opt-in security feature, rather than opt-out means that most users will not enable it. No exact numbers are publicly available about 2 Factor adoption rates, but if it looks like other opt-in choices (e.g. seat belts before being made mandatory), it is unlikely to be adopted by a majority of users. While there are trade-offs to enabling 2 factor as a default (e.g. costs to account recovery and friction in user experience), reports like this one make it clear that credential phishing will continue to be widely practiced by a range of threat actors against some of the most vulnerable user groups.

Conclusion: Nile Phish Is Yet Another Threat to Egypt’s Civil Society

Egyptian NGOs have faced a sprawling legal case that is in its fifth year. The case has resulted in arrests, travel bans, asset freezes, and prison sentences. Almost all of the 92 phishing emails we have identified were sent to individuals implicated in Case 173, either as named defendants, or staff of targeted NGOs.

We do not attribute Nile Phish to a sponsor in this report, but it is clear that it is yet another component of the increasingly intense pressure faced by Egyptian civil society. By exposing the Nile Phish operation, including providing more technical indicators, we hope to help potential targets and other investigators identify and mitigate the campaign.

Evidence of Two Factor Phishing

Since publication, Citizen Lab and EIPR have been contacted by a number of additional targets. These targets provided us with a range of evidence for additional activities by Nile Phish. Importantly, it also appears that Nile Phish has engaged in phishing users of 2 factor authentication. The following illustration describes this process.

The phishing works in this case by tricking the victim into entering both their password and their two factor code. First, the victim is phished by Nile Phish using a deception similar to those described in the report. If the victim is tricked into providing their password, Nile Phish sends the victim a message with a link to a 2-factor code phishing page, then the operators type the stolen password into Gmail. They then request SMS as an Alternative Verification method. Gmail then sends the victim an SMS with a six digit code. If the victim enters the SMS into the code phishing page, the operators use the code to log into gmail to take control of the account.

Acknowledgements

Very special thanks to Citizen Lab colleagues including Ron Deibert, Claudio Guarnieri, Sarah McKune, Ned Moran, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Irene Poetranto, Adam Senft, and Amitpal Singh.

Citizen Lab also thanks T. Nebula, unnamed security researchers, TNG, and Internews.

Appendix A: Indicators of Targeting

Download the indicators from the Citizen Lab Github.

The operators used at least 33 domains for this phishing attack, the following table provides examples.

| Theme | Example Domain |

|---|---|

| googledrive-sign.servehttp[.]com, googledriver-sign.ddns[.]net, mailgooglesign.servehttp[.]com, google-maps.servehttp[.]com, account-google.serveftp[.]com, googleverify-signin.servehttp[.]com, googlesecure-serv.servehttp[.]com, googlesignin.servehttp[.]com, activate-google.servehttp[.]com, googlemaps.servehttp[.]com | |

| Dropbox | dropboxsupport.servehttp[.]com, dropbox-service.serveftp[.]com, dropbox-sign.servehttp[.]com |

| Generic | verification-acc.servehttp[.]com, secure-team.servehttp[.]com, security-myaccount.servehttp[.]com, myaccount.servehttp[.]com, device-activation.servehttp[.]com |

| Shipping | fedex-shipping.servehttp[.]com, fedex-mail.servehttp[.]com, fedex-sign.servehttp[.]com, aramex-shipping.servehttp[.]com |

Full List of Domains

account-google.serveftp[.]com

aramex-shipping.servehttp[.]com

device-activation.servehttp[.]com

dropbox-service.serveftp[.]com

dropbox-sign.servehttp[.]com

dropboxsupport.servehttp[.]com

fedex-mail.servehttp[.]com

fedex-shipping.servehttp[.]com

fedex-sign.servehttp[.]com

googledriver-sign.ddns[.]net

googledrive-sign.servehttp[.]com

google-maps.servehttp[.]com

googlesecure-serv.servehttp[.]com

googlesignin.servehttp[.]com

googleverify-signin.servehttp[.]com

mailgooglesign.servehttp[.]com

myaccount.servehttp[.]com

secure-team.servehttp[.]com

security-myaccount.servehttp[.]com

verification-acc.servehttp[.]com

dropbox-verfy.servehttp[.]com

fedex-s.servehttp[.]com

watchyoutube.servehttp[.]com

verification-team.servehttp[.]com

securityteam-notify.servehttp[.]com

secure-alert.servehttp[.]com

quota-notification.servehttp[.]com

notification-team.servehttp[.]com

fedex-notification.servehttp[.]com

docs-mails.servehttp[.]com

restricted-videos.servehttp[.]com

dropboxnotification.servehttp[.]com

moi-gov.serveftp[.]com

activate-google.servehttp[.]com

googlemaps.servehttp[.]com

IPs

108.61.176[.]96

104.238.191[.]204

176.123.26[.]42

Emails

secure.policy.check[@]gmail.com

aramex.shipment[@]gmail.com

fedex_tracking[@]outlook.sa

mails.acc.noreply[@]gmail.com

fedex.noreply[@]gmail.com

customerserviceonlineteam[@]gmail.com

fedexcustomers.service[@]gmail.com

elnadeem.org[@]gmail.com

dropbox.noreplay[@]gmail.com

mails.noreply.verify[@]gmail.com

fedex.mails.shipping[@]gmail.com

dropbox.notifications.mails[@]gmail.com

dropbox.notfication[@]gmail.com

drive.noreply.mail[@]gmail.com