Managing the Message

What You Can’t Say About the 19th National Communist Party Congress on WeChat

The 19th National Communist Party Congress was held from October 18-24, 2017. WeChat, China’s most popular chat app, blocked a broad range of content related to the Congress.

Key Findings

- WeChat censored keywords related to the 19th National Communist Party Congress over a year prior to the event and updated blocked content as the event approached.

- Surprisingly, we found that even neutral references to official party policies and ideology were blocked in addition to references to the Congress, party leaders, and power struggles within the Communist Party of China.

Summary

From October 18 to October 24 2017, the Communist Party of China (CPC) held its 19th National Communist Party Congress (NCPC19), which marked the halfway point of President Xi Jinping’s 10-year term, and served as a bellwether of his power over the party. The National Communist Party Congress (NCPC) is the most important political event for the CPC, and information around it is carefully managed. For months reports have circulated of new regulations and restrictions over the Internet in China attributed to “stability maintenance” procedures put in place in anticipation of the Congress. In this report we take an in-depth look at how WeChat, the most popular chat app in China, censored content related to the NCPC19.

We tested samples of keywords extracted from news articles reporting on the Congress and documented which of them triggered censorship on WeChat’s group chat feature. We found keywords blocked over a year prior to the Congress and tracked censorship updates as it approached. A broad range of content was censored including criticism and general speculation around the Congress, leaders, and power struggles. In the weeks leading up to the Congress we found blocked keywords that referenced central government policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, and core ideological concepts like “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics”.

Blocking government criticism in advance of the NCPC19 could be a means to prevent the spread of messaging that is destabilizing to the Party during a crucial moment. Censoring speculation and rumours concerning leaders and power struggles within the party may also be motivated by an effort to project images of power and unity and help leaders save face or avoid embarrassment. The intent behind blocking references to central policies and ideologies of the CPC is less clear. Censoring this content restricts benign discussions and potentially even pro-government messages. This wide scope may be due to WeChat proactively over-blocking content around a topic it knows is highly sensitive to avoid official reprimands, or may be part of a government strategy to manage online discussions and public opinion. While the underlying decision making behind the blocking is not clear, it is apparent that a broad brush was applied to censorship of the NCPC19 on WeChat.

Background

Major political events in China are routinely met with increased censorship, heightened security, and propaganda including reactive censorship on social media platforms. For example, following the passing of Liu Xiaobo, censorship of keywords related to Liu on WeChat became more expansive and blunt to the extent that any mention of his name was restricted.

The functions of the NCPC include confirming personnel changes at the central level, revising ideological principles in the party constitution, and adjusting the national development strategy. Periods of power transition like the NCPC can trigger uncertainty and insecurity in authoritarian regimes, making controlling messaging around such events critically important.

Following months of intense speculation over how Xi may further his influence at the NCPC19, the Congress concluded with Xi reaching a new height of power. The CPC revised its constitution to include reference to a doctrine of Xi’s political theory (“Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”), making Xi the third leader to have his name enshrined in the constitution following Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Allies of Xi took on high-ranking positions, including on the Politburo Standing Committee. But the seven man committee did not include a clear successor to Xi, breaking with leadership transition traditions and creating uncertainty over whether Xi will pursue a third term, which would go against the norm of a 10-year limit for the Chinese presidency.

The NCPC19 has been described by the media and analysts as a catalyst for a range of information controls enacted in the past year including increased restrictions on access to international platforms and regulations aimed at domestic companies and individual users in China.

In January 2017, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced that virtual private networks (VPNs) which can be used to circumvent China’s national web filtering system (commonly known as the Great Firewall of China) must be authorized by state-run telecoms. In July Apple announced that it was removing VPN applications from the App Store in China to comply with the new law. In September, reports circulated that WhatsApp was blocked in China. It is not unusual in China for international platforms that are out of reach of direct state control to be the target of increased restrictions during sensitive political periods. In a more dramatic shift, the Chinese government passed regulations that pushed liability and penalizations down to individual users.

Between August and September, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), China’s top-level Internet governance body, released four major regulations on Internet management, ranging from strengthening real-name registration requirements on Internet forums and online comments, to making individuals who host public accounts and moderate chat groups liable for content on the platforms (see Table 1 for an overview of the regulations). These regulations push responsibility down to individual users rather than at the level of media and technology companies that previous regulations targeted. David Bandurski describes this change as evidence of the “atomization and personalization of censorship” in China.

| Regulation | Rule |

|---|---|

| Internet Forum Service Management Regulation (互联网论坛社区服务管理规定) | Article 8: Users should be denied service if they do not register under their real identities for online forums and message boards. |

| Internet Thread Comments Service Management Regulation (互联网跟帖评论服务管理规定) | Article 9: Providers of commenting and posting services should create a credit system where users will receive ratings that determine their scope of service. Severe violators of regulations should be blacklisted and denied future services. Governments should keep a credit file on users. |

| Internet User Public Account Information Services Management Regulation (互联网用户公众账号信息服务管理规定) | Article 6: Internet users must provide their organization, national identity documents and mobile phone numbers or be denied service.

Article 13: Companies should also set up credit rating systems tied to user accounts. |

| Management Rules of Internet Group Information Services (互联网群组信息服务管理规定) | Article 4: Providers of information services through internet chat groups and users must adhere to correct guidance, promoting socialist core values, fostering a positive and healthy online culture, and protecting a favourable online ecology. |

Overview of Internet regulations released by the Cyberspace Administration of China in 2017.

In August, the CAC announced that Sina Weibo, Tencent, and Baidu were under investigation for hosting content that “endangered national security, public security and social order.” In September, the companies were fined as a result of the investigation, which found the platforms failed to properly manage prohibited content.

In early September, China Digital Times published a leaked government-issued media directive on the NCPC19, which instructed media not to spread rumours, use only Xinhua News Agency wire copy as standard news releases, and have all interviews with experts or scholars approved by the Central Propaganda Department.

On October 17, a day prior to the start of the NCPC19, WeChat, QQ, and Weibo announced that users will not be able to change their profile pictures, usernames or personal biographies until the end of October due to “system maintenance.” While Weibo has previously employed such tactics and froze certain features (e.g. disabling the candle emoji around Tiananmen Square Movement anniversaries), WeChat has not.

Methodology

Our documentation of NCPC19 related censorship on WeChat follows a method we developed in previous work that has been shown to reliably track event-based keyword blocking over a given period.

How WeChat Censors Keywords

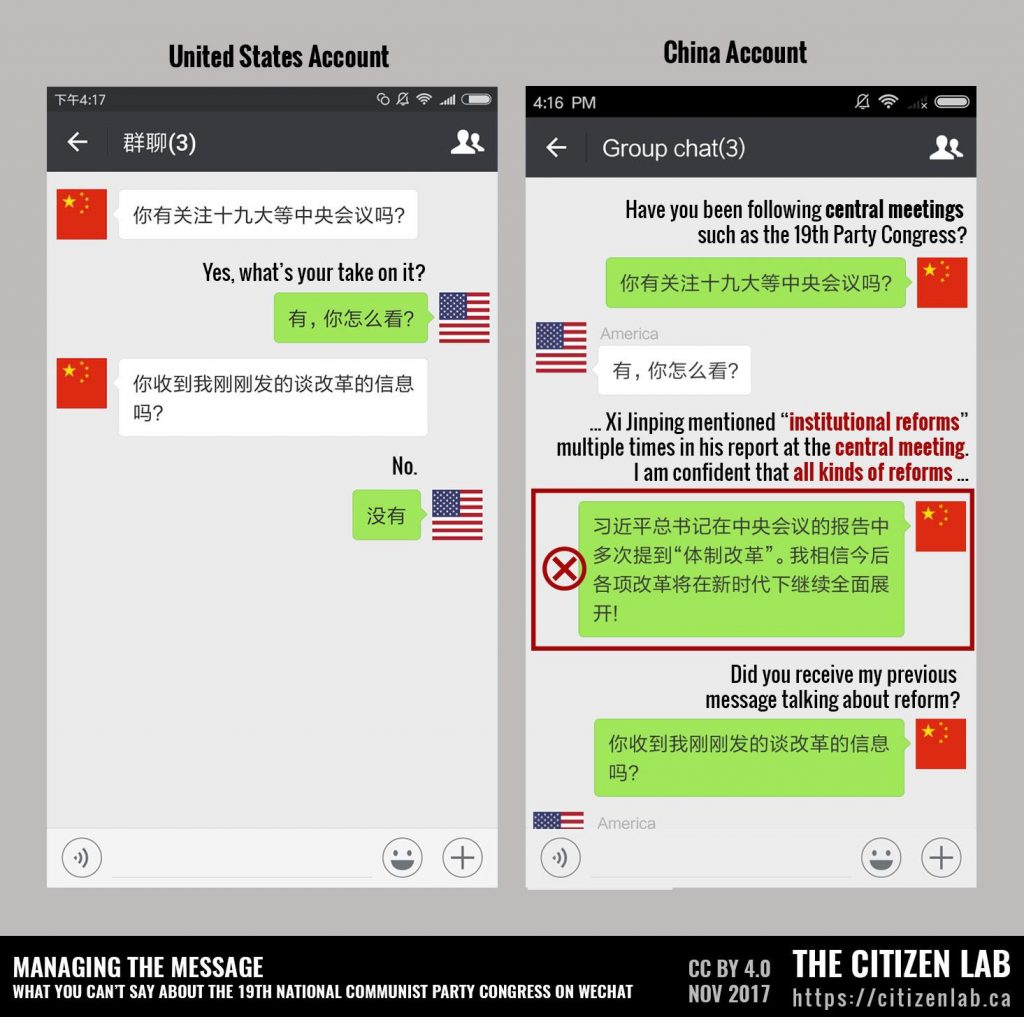

WeChat keyword-based censorship is enabled for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. Censorship for these accounts persists even if these users later link the account to a number outside of mainland China. The censorship is not transparent: a message containing a sensitive keyword simply does not appear on the receiver’s end and no notice is given to the sender that their message is blocked or why it was blocked. We found in prior work that compared to one-to-one chat, more keywords are blocked on group chat, where messages can reach an audience of up to 500 users.

WeChat performs censorship on the server-side, which means that messages pass through a WeChat server that contains rules for implementing censorship. If the message includes a keyword combination that has been targeted for blocking, the entire message will not be received. Documenting censorship on a system with a server-side implementation requires devising a message of one or more keywords to test, running that message through the app, and recording the results.

WeChat censors a message based on whether it contains a blacklisted keyword combination. A keyword combination consists of one or more keyword components, and a message is filtered if it contains every component in a blacklisted keyword combination somewhere in the message, even if they are not adjacent. For example, if a blacklisted keyword combination consists of only one component (e.g., “劉曉波”), then a message is filtered if it contains that component anywhere. As another example, if a keyword combination contains two components (e.g., “刘晓波” and “习近平”), a message is filtered if both components appear somewhere in the message. Combinations with a larger number of components are able to more precisely target content.

Testing Sample

We extracted keyword combinations from front page articles of Chinese-language international media, independent media, and state media to use as a testing sample (see Appendix A). In previous work we found that extracting keywords from these news sources was effective for tracking events and themes that are subject to censorship over a defined time period. We used a script to collect URLs to news articles, using RSS to identify articles with tags relevant to NCPC19 (e.g., 十九大, 中共人事).

Testing Method

We extracted the title and body text from each article and sent it as a message in a WeChat group chat using three test accounts. Two accounts were registered to Canadian or American phone numbers, one to send text and a second to act as a “third wheel” so that the chat would be considered a group chat. Another account was registered to a mainland China phone number. If this account did not receive article text sent by another account in the group chat, we determined that the text triggered filtering, and we then performed subsequent tests to reduce the article to the minimum number of words and characters required to trigger censorship.

Observation Period

Our keyword testing was conducted during two periods.

Between July 2016 to August 2017, we ran tests using a sample of keywords extracted from front page articles of Chinese-language international and independent news media websites.

Between September 22 to October 25 2017, we refined our testing sample to include articles with NCPC19 RSS tags collected from official state media, international media, Hong Kong-based media, and news and censored content aggregation websites (see Appendix A). Tests were run twice weekly during this period.

Results

Between July 2016 and August 2017, we found 51 unique keywords blocked, and 194 keywords blocked between September 22 to October 25 2017, for a total of 241 unique keywords blocked between both periods. The greater number of keywords found blocked in the second testing period is likely due in part to our more focused testing sample of articles with NCPC19 RSS tags and a higher volume of articles published about the Congress during that time. These results may also reflect WeChat placing a heightened focus on Congress related content in the period closer to the event.

The results of documenting server-side keyword based censorship are only as accurate as the intersection between the sample of keywords tested and what content the platform targets for blocking. Previous work has shown that censorship on WeChat is dynamic, new keywords are added to block lists and previously blocked keywords may later become accessible. Our results report on the first instance that we found a keyword blocked. Therefore, we do not have a comprehensive view into NCPC19 blocking on WeChat. What our results provide is a snapshot of how content was censored during our testing period, and shows keywords were blocked over a year before the congress and updated as it approached.

Content Analysis

We translated each keyword to English and based on interpretations of the underlying context grouped them into content categories. We further grouped these categories into high-level themes that reflect the focus of censorship: the Congress, the reputation of Xi, the image of the party (including references to internal power struggles and party policy and ideologies), and discussions of information controls implemented in anticipation of the Congress.

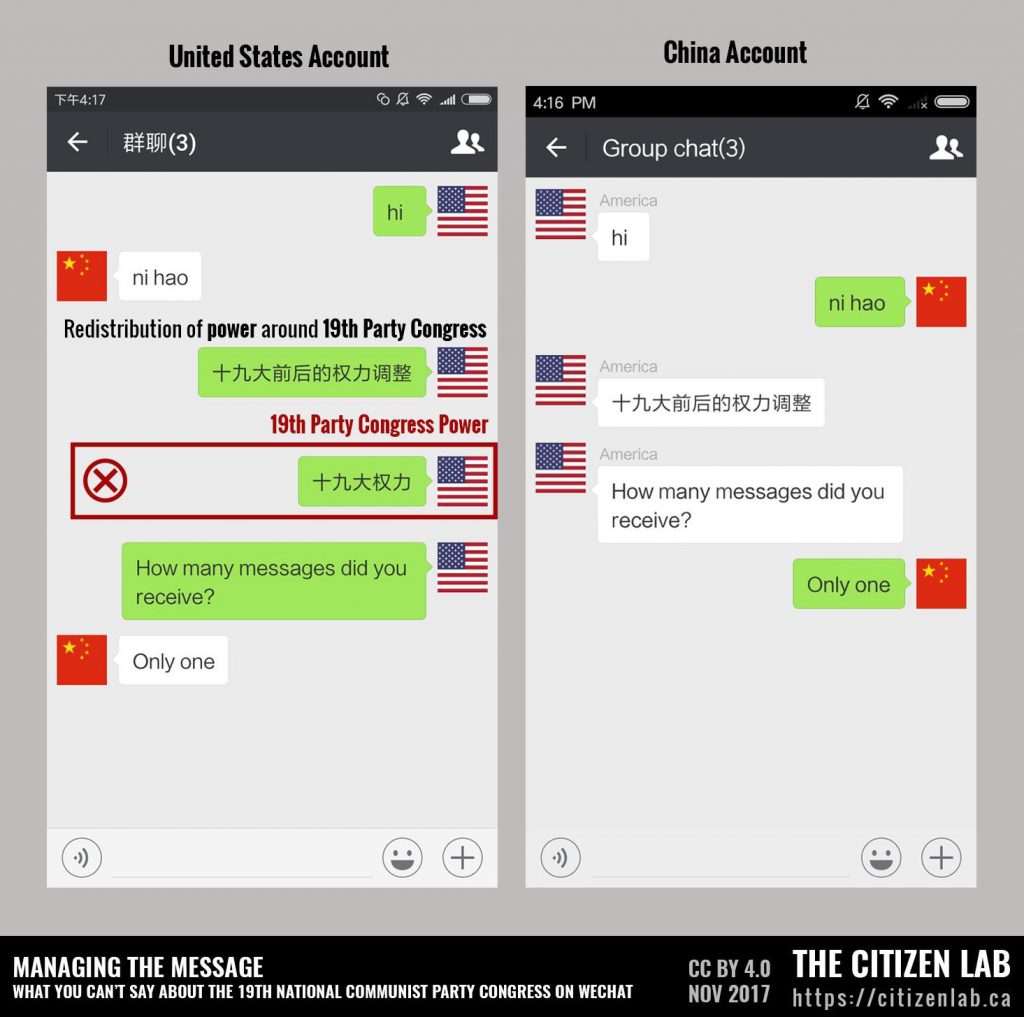

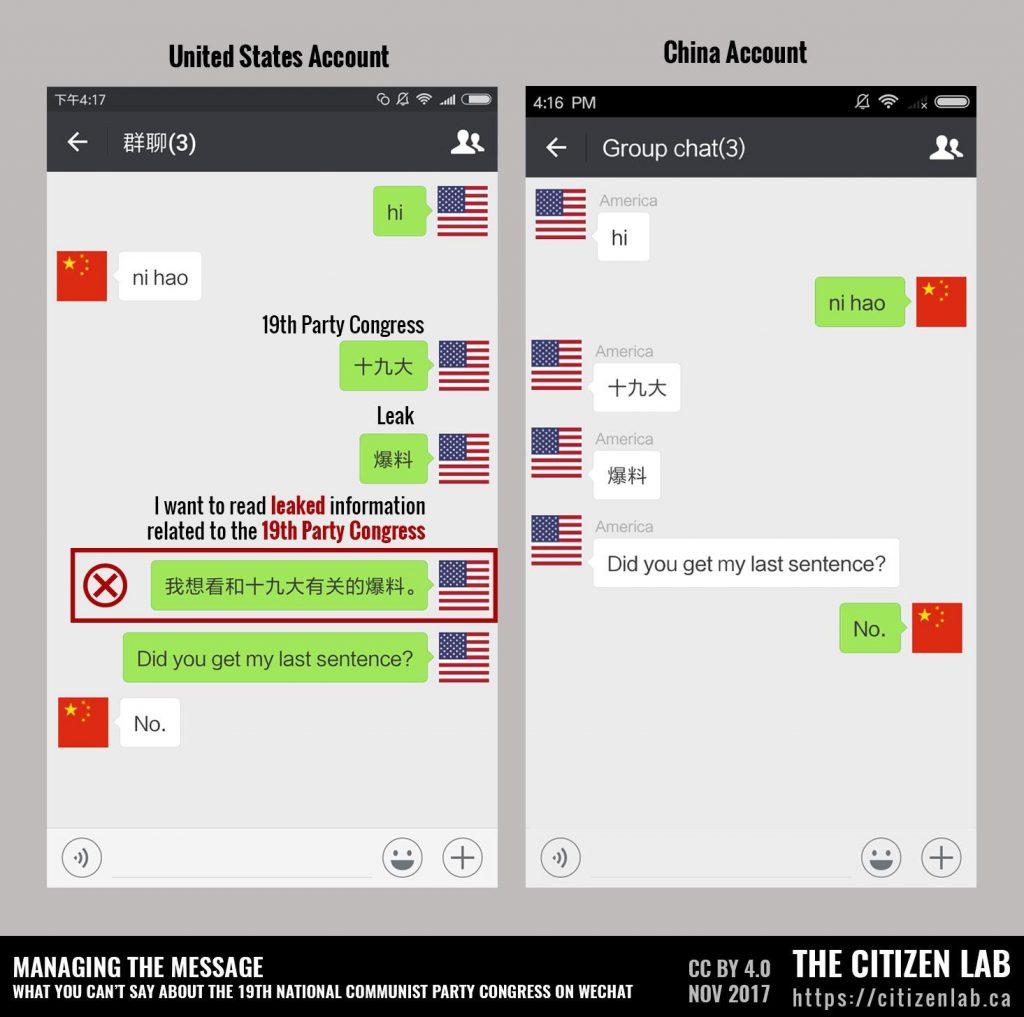

General and Critical References to the 19th Party Congress

Blocked keywords ranged from generic references that would restrict benign discussions of the Congress to keywords that were more obviously critical. General references included “19th Party Congress power” (十九大权力), and “Beidaihe meeting”, (北戴河会议), a closed annual gathering that brings together elite party members at a beach resort for discussion of policy issues, which is particularly sensitive this year in lead up to NCPC19. These keywords were blocked months before the Congress and would trigger censorship if they are present in any part of a message (See Figure 1).

Prior to the Congress more critical references included “19th Party Congress + leak” (十九大+爆料) and “19th Party Congress + sabotage” (十九大+去破坏). These keyword combinations would trigger blocking if all the keyword components were present anywhere in the message. If the keyword components were sent individually, the message would go through (see Figure 2).

Near the closing of the Congress, we found more specific references such as criticism of the lack of female party representatives: “19th Party Congress + female issue + break [glass ceiling] in political career” (十九大+女性问题+突破政坛). This example shows keywords were updated in reaction to news stories and issues that emerged as the Congress unfolded.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 19大人事 | 19th Party Congress personnel | June 21 2017 |

| 北戴河会议 | Beidaihe meeting | June 27 2017 |

| 十九大权力 | 19th Party Congress Power | July 21 2017 |

| 十九大+爆料 | 19th Party Congress + leak | July 25 2017 |

| 十九大+去破坏 | 19th Party Congress + sabotage | September 22 2017 |

| 十九大+女性问题+突破政坛 | 19th Party Congress + female issue + break [glass ceiling] in political career | October 24 2017 |

Managing Xi’s Reputation

Seventy-three unique keywords were thematically linked to Xi Jinping, his reputation, and speculation and news surrounding his consolidation of power at the NCPC19. These keywords include criticism, but also general references.

A selection of keywords made critical references to Xi, such as describing him as a dictator, the Congress as his personal show, and highlighting his record in suppressing human rights.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 十九大+习近平+迫切地打造个人舞台 | 19th Party Congress + Xi Jinping + eagerly build his personal show | March 6 2017 |

| 独裁+近平 | dictatorship + Jinping | October 18 2017 |

| 习近平+十九大+打压人权 | Xi Jinping + 19th Party Congress + suppress human rights | October 25 2017 |

Other keywords were neutral references to Xi’s second term, and his nationalistic slogan of the “Chinese Dream”, which is part of his overall political doctrine and agenda.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 中共十九大+習近平+中國夢 | CCP 19th Congress + Xi Jinping + China dream | July 19 2017 |

| 习近平+十九大+第二任期 | Xi Jinping + 19th Party Congress + second term | September 27 2017 |

Keywords included general speculations over Xi’s consolidation of power at the NCPC19, possible breaks with leadership transition norms, and personnel shifts.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 中共19大+巩固习近平+政治权威 | CCP 19th Congress + Solidify Xi Jinping[‘s power] + Political Authority | May 20 2017 |

| 习近平+打破十年制任期+可能性不高 | Xi Jinping + Broke ten-year term limit + Possibility is not high | May 24 2017 |

| 习近平+十九大+巩固权力 | Xi Jinping + nineteenth + power to consolidate | July 18 2017 |

| 破坏了习近平+等级顺序+换届规则 | sabotaged Xi Jinping + ranking order + norms of term transition | July 24 2017 |

| 三连任+习近平 | three consecutive terms + Xi Jinping | October 13 2017 |

Keywords also referenced speculation over Xi’s thoughts being written into the Party constitution and were detected as blocked in the weeks leading up to the Congress and at the close of the event when the revisions to the constitution were announced.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 习核心+写入党章+十九大 | Xi core + written to party constitution + 19th Party Congress | September 25 2017 |

| 修改党+章+习思想+十九大 | amend party constitution + Xi Thoughts + 19th Party Congress | September 25 2017 |

| 习思想+入党章+外媒 | Xi Thought + written to party constitution + foreign media | September 28 2017 |

| 与毛邓并驾齐驱+习近平 | on par with Mao [Zedong] and Deng [Xiaoping] + Xi Jinping | October 17 2017 |

| 中共领导人+写入党章+掌权+毛泽东 | CCP leader + written to party constitution + hold onto power + Mao Zedong | October 25 2017 |

Censoring critical references to Xi follows general trends of government criticism being restricted on social media in China. Blocking this content could be means to control dissent, but also an effort to ensure leaders “save face” and are not presented in disparaging ways. The more surprising finding is the censorship of generic references to Xi and speculations over his consolidation of power. Censoring this content could be a means to control messaging and agenda setting around the Congress.

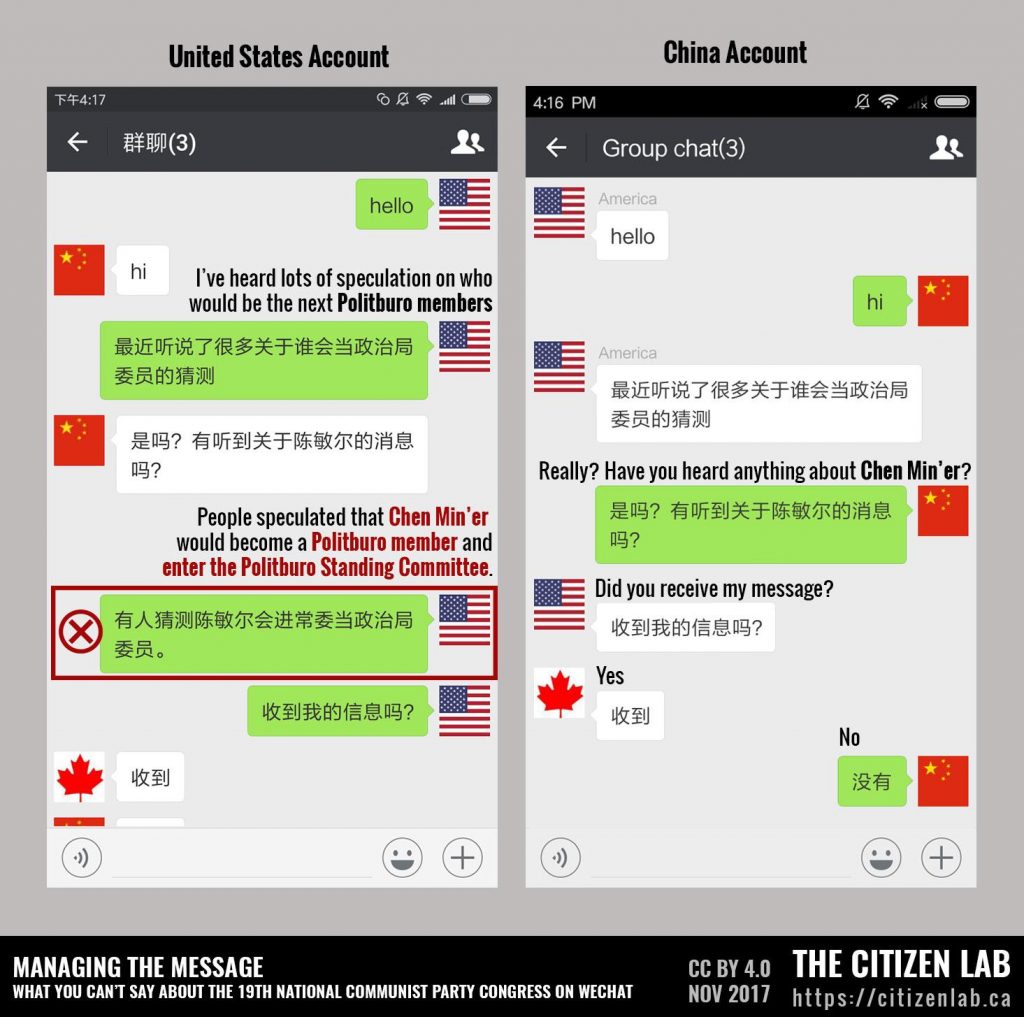

Power Struggle

Seventy-four of the blocked keywords were thematically linked to power struggles, personnel transitions, and factionalism in the CPC. It is possible that these keywords were censored to project a sense of unity, which is crucial for authoritarian regimes during critical and sensitive periods such as major power transitions.

Smooth power transition has been a challenge through the CPC’s history. Rather than institutionalizing the process, personnel transitions are often influenced by patronage networks based on family ties, personal contacts, and where individuals work. Blocked keywords include references to major political factions within the party, such as the Communist Party Youth League clique (团派), which is composed of cadres who came up through the Communist Youth League of China and is former President Hu Jintao’s base of power, and the Shanghai Clique (上海帮) or Jiang Clique (江派), the power base of former leader Jiang Zemin, who resides in Shanghai and retains political influence through proteges.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 团派+十九大+江派 | [Communist Party Youth] League Clique + 19th Party Congress + Jiang Clique | March 27 2017 |

| 上海帮+江泽民 | Shanghai Clique + Jiang Zemin | October 13 2017 |

Prior to the NCPC19, personnel movements in the CPC fueled speculations that Xi was pushing out political rivals and positioning allies for top ranking positions. The most dramatic of these movements was the ouster of Sun Zhengcai from the CPC. Sun was Communist Party Secretary of Chongqing and seen as likely to assume a high ranking role at the NCPC19. He was removed from his post in July and accused of “violating party discipline”, a euphemism for corruption or disloyalty to the party. In September, state media announced that Sun was expelled from the CPC, stripped of all official titles, and would face criminal prosecution. Chen Min’er a protege of Xi replaced Sun as Party Secretary of Chongqing. During a session of the NCPC19, China’s securities commission chairman Liu Shiyu described Sun as part of a plot to seize power from Xi. This accusation could be both a clear signal to party members to remain loyal and a sign of power struggles within the party.

We first found blocked keywords referencing the expulsion of Sun and promotion of Chen in July. During the Congress we found blocked keywords related to the possible movement of Chen into the Politburo and Sun’s alleged intentions to seize power (see Figure 3).

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 陈敏尔+中共+政治新星+另有任用 | Chen Min’er + CPC + political star + another appointment | July 18 2017 |

| 孙政才 + 中共 + 明日之星 + 政治牺牲品 | Sun Zhengcai + CCP + Rising Star + Sacrifice of Politics | July 24 2017 |

| 孙政才落马+邓小平制定的接班制度+全面崩溃 | Sun Zhengcai downfall + term transition norms set by Deng Xiaoping + collapsed | July 25 2017 |

| 孙政才落马+习近平欲破+中共四大约法 | Sun Zhengcai downfall + Xi jinping wants to break + CPC’s norm since the 4th Party Congress | July 25 2017 |

| 孙政才+路线+斗争+急急表态 | Sun Zhengcai + party line + power struggle + eager to show stance | July 26 2017 |

| 入常+连跳两级+陈敏尔 | enter the Politburo + jump two ranks up + Chen Min’er | October 11 2017 |

| 夺取共产党+孙政才+控制权 | rob the CCP + Sun Zhengcai + control power | October 23 2017 |

Prior to the NCPC19, speculation also centred on whether Wang Qishan, a close ally of Xi, would retire. According to CPC norms, officials must retire if they reach age 68 by the time of the NCPC. Wang is aged 69 and media debated if convention would be followed or if he would be kept on for another term. Wang ultimately retired following party norms. Blocked keywords referenced these speculations.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 七上八下+中共+十九大 | [Sixty-]seven promotes [sixty-]eight retires + CPC + 19th Party Congress | September 26 2017 |

| 十+九+大+王岐山+去留 | Ten + Nine + Big + Wangqishan + stay or go | October 11 2017 |

| 王岐山+留任 | Wang Qisan + remain in power | October 13 2017 |

Party Policies and Ideology

In the weeks leading up to the Congress, we found find 37 blocked keywords that made neutral references to CPC ideologies and central policy including major policy programs such as the Belt and Road Initiative and key CPC concepts such as “Socialism with Chinese characteristics.” These keywords were extracted from news articles published by state media outlet Xinhua News Agency, (a source that government authorities instructed media units to use as a reference in coverage of the NCPC19), and official government WeChat public accounts.

| Keyword | Translation | Date Tested | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 一带一路+丝绸之路经济带+建设+构想 | Belt and Road + economic belt of the Silk Road + construct + picture | October 6 2017 | Offical WeChat Public Account of Xinjinag Daily, an official publication of the CPC Xinjiang Committee |

| 反腐败+斗争+自信+足够 | anti-corruption + fight + confidence + enough | October 11 2017 | Official WeChat public account of a Guizhou-based government agency |

| 中央+会议+体制改革+各项改革 | Central [government] + meeting + structural reform + all kinds of reforms | October 12 2017 | Xinhua News |

| 会议+召开+指导意见+深改组 | meetings + convene + guidance + Comprehensively Deepening Reforms | October 12 2017 | Xinhua News |

| 中国特色社会主义+全面依法治国+宪法+法律 | Socialism with Chinese characteristics + comprehensive rule of law + constitution + law | October 13 2017 | Xinhua News |

Blocking these keywords could restrict general and potentially even pro-government conversations about the NCPC19 (see Figure 4).

Censoring these keywords may be due to WeChat proactively over-blocking content around a topic it knows is highly sensitive to avoid official reprimands, or may be part of a government strategy to manage online discussions and public opinion. Unlike traditional media or the WeChat public account platform where articles are vetted before publication, discussions on chat apps are more difficult to predict and manage.

Information Control

Twenty-three keywords referenced censorship and information controls related to the NCPC19, such as increased regulations on VPNs and circumvention of China’s web filtering system (colloquially referred to in Chinese as “jumping over the Great Firewall”). Others referenced restrictions on movements into Tibetan areas in the lead-up to the Congress.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 封殺VPN + 習近平完成集權 + 十九大 | block VPN + Xi Jinping finishes consolidating power + 19th Party Congress | July 25 2017 |

| 当局+严格的控制+寻求翻墙+十九大 | authorities + strict control + seek to jump over the [Great Fire] Wall + 19th Party Congress | July 25 2017 |

| 入藏+十九大+外国人+禁止 | enter Tibet + 19th Party Congress + foreigners + forbidden | September 27 2017 |

Keywords also referenced sudden censorship of films and television. On September 12, 2017, Hong Kong-based Phoenix TV announced the termination of its signature program Behind the Headlines with Wen Tao (锵锵三人行), which had been on air since 1998 and was one of the most popular news talk shows among Chinese audiences.

Youth, a film by Feng Xiaogang, faced a similar fate. The film was scheduled to premiere in China on September 29, 2017, but just five days before its launch all ticket sales were halted and its release date was put off indefinitely. The film follows the story of a People’s Liberation Army art troupe (文工团) from the chaotic Cultural Revolution to the 1990s, including the period of the Sino-Vietnamese War in 1976. Media reports cited sources with ties to censorship authorities who claimed the film was seen as politically risky to release before the NCPC19 because of its depiction of the Sino-Vietnamese War, which remains a politically sensitive event.

| Keyword | Translation | Date tested |

|---|---|---|

| 官方紧张心态+牺牲品+芳华 | authorities are nervous + sacrifice + Youth [Film Title] | September 26 2017 |

| 19大+锵锵三人行 | 19th Party Congress + Behind the Headlines with Wen Tao | September 27 2017 |

| 入藏+十九大+外国人+禁止 | enter Tibet + 19th Party Congress + foreigners + forbidden | September 27 2017 |

| 中越战争+外界猜测+撤档+芳华 | Sino-Vietnamese war + speculates + take off the showtime schedule + Youth | September 29 2017 |

Conclusion

Leaked directives and previous research show that Chinese social media companies receive greater government pressure during sensitive events. The blocking of NCPC19 on WeChat is an example of how expansive blocking of a political event can be. Keywords related to the Congress were censored well over a year before the event itself. The scope of censored content went beyond criticism of the government or representations of collective action to target general discussions of the event and speculations into its outcomes.

It is unclear what level of guidance Tencent received from authorities on how to manage NCPC19 content on WeChat. However, given the sensitivity of the event and the results of our study it is clear that the company faced direct or indirect government pressure to ensure content was properly managed. The broad range of censored content may be due to Tencent proactively over-blocking content around a topic it knows is highly sensitive to avoid official reprimands, or it may also be part of a wider government strategy to manage online discussions and public opinion.

As the Congress fades into the distant past, it is possible that censorship surrounding the event will change. In a study of censorship on Sina Weibo related to the 18th Party Congress, Jason Q. Ng found that after the event the volume of censorship on the platform decreased. This shift could be an attempt by authorities to find a balance between monitoring public opinion and restricting content, or Sina loosening restrictions around it when it was no longer under close scrutiny. We will continue to monitor how discussions of the NCPC19 are treated on WeChat to determine if similar patterns emerge.

Xi’s second term poses higher level questions for social media censorship in China. One of Xi’s central focuses in his first term was targeting perceived threats to the CPC and cracking down on dissent, including efforts to “clean up and manage the Internet”. What character will information controls take in his second term? Will regulations targeting individual users expand and be reinforced? Will the blunt censorship of sensitive events that we have observed continue? Will censorship advance from passive, reactive information blocking to more proactive public opinion shaping? We can gain insights into these questions by continuing to analyze how discussions of major political events in China are treated on social media.

Acknowledgements

This report is by Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Lotus Ruan, (co-lead authors), Jakub Dalek, and Jeffrey Knockel. Graphics by Andrew Hilts. The authors thank Ruohan Xiong for research assistance and Ron Deibert, Jason Q. Ng, Adam Senft, and Lokman Tsui, for review and comments.

Data

Full list of blocked keywords are available on Github.

Appendix A: Article Sources

| Source | Type | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Xinhua News | China State Media | Xinhua News Agency (新华社) is the official press agency of the People’s Republic of China. |

| The Global Times | China State Media | The Global Times (环球时报) is a state-run Chinese newspaper affiliated with the People’s Daily. |

| People’s Daily | China State Media | The People’s Daily (人民日报) is the official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party. |

| The Paper | China State Media | The Paper (澎湃) is a Shanghai-based state-funded Chinese media site. |

| BBC Chinese | International Media | The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster. Its Chinese website reports on China issues. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Deutsche Welle Chinese | International Media | Deutsche Welle is Germany’s public international broadcaster. Its Chinese website focuses on mainland China and Europe-China news. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Financial Times Chinese | International Media | The Financial Times, published and owned by Nikkei Inc. in Tokyo, is an international daily newspaper. Its Chinese website focuses on business and financial news in China, with occasional reporting and commentaries on Chinese politics and foreign policy. |

| The New York Times Chinese | International Media | The New York Times is an American daily newspaper. Its Chinese site has been blocked in China since 2012 when it published an article on the wealth of former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s family. |

| Radio Free Asia Mandarin | International Media | Radio Free Asia (自由亚洲电台) is a private non-profit international broadcasting corporation funded by the Broadcasting Board of Governors, an independent agency of the US government. It publishes news on East Asia while “advancing the goals of U.S. foreign policy.” Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Radio France Internationale Chinese | International Media | Radio France Internationale is a French public radio service. Its Chinese-language radio service first started in June 1989. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Voice of America Chinese | International Media | Voice of America is a United States government-funded multimedia news source. Its Chinese website primarily focuses on mainland China news. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Lianhe Zaobao | International Media | Lianhe Zaobao (联合早报) is the largest Singapore-based Chinese-language newspaper. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| The Initium Media | Hong Kong-based Media | Launched in 2015, the Initium Media (端传媒) is a Hong Kong–based digital media outlet that provides Chinese-language news. |

| Ming Pao | Hong Kong-based Media | Ming Pao (明報) is a Hong Kong based newspaper known for its reporting on political and economic issues in mainland China and Hong Kong. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| Oriental Daily | Hong Kong-based Media | Oriental Daily (東方日報) is a news website of the Oriental Press Group, a large Hong Kong media publisher. Its website is currently blocked in China. |

| South China Morning Post | Hong Kong-based Media | The South China Morning Post is a Hong Kong-based English-language newspaper. |

| FreeWeChat | Censored content aggregation site | FreeWeChat (自由微信) is a website managed by non-profit group GreatFire, which tracks censored and deleted posts on WeChat public accounts. |

| FreeWeibo | Censored content aggregation site | FreeWeibo (自由微博) is a website managed by non-profit group GreatFire, which tracks censored and deleted posts on Sina Weibo. |

| letscorp | News aggregation site | Qiangwailou (墙外楼) is a website that tracks trending posts on Chinese social media including blocked content. |

| qiwen.lu | News aggregation site | Qiwenlu (奇闻录) is a news aggregation site that documents trending Chinese news and discussions. It primarily focuses on political humor, or duan zi (段子). |