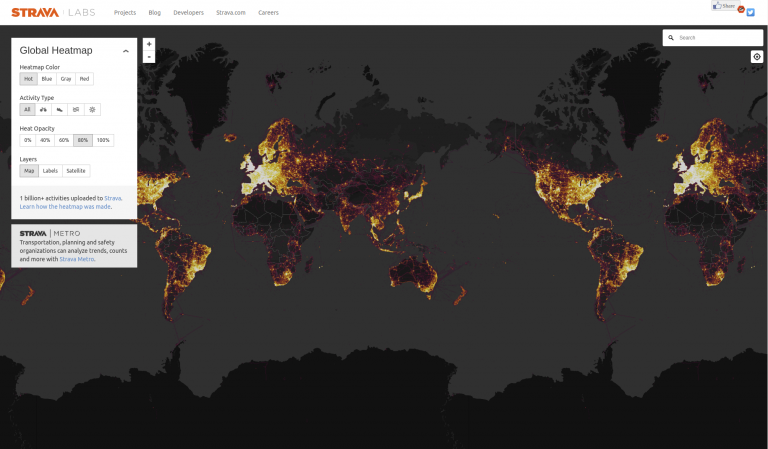

Fitness apps can be great tools for motivating and keeping track of physical activity. Unfortunately, they can also blow your cover. In Fit Leaking: When a Fitbit Blows Your Cover, Citizen Lab Senior Researcher John Scott-Railton coins the term ‘Fit Leaking’ to describe how how one company’s “God’s Eye View” of fitness data reveals large amounts of secret and private information.

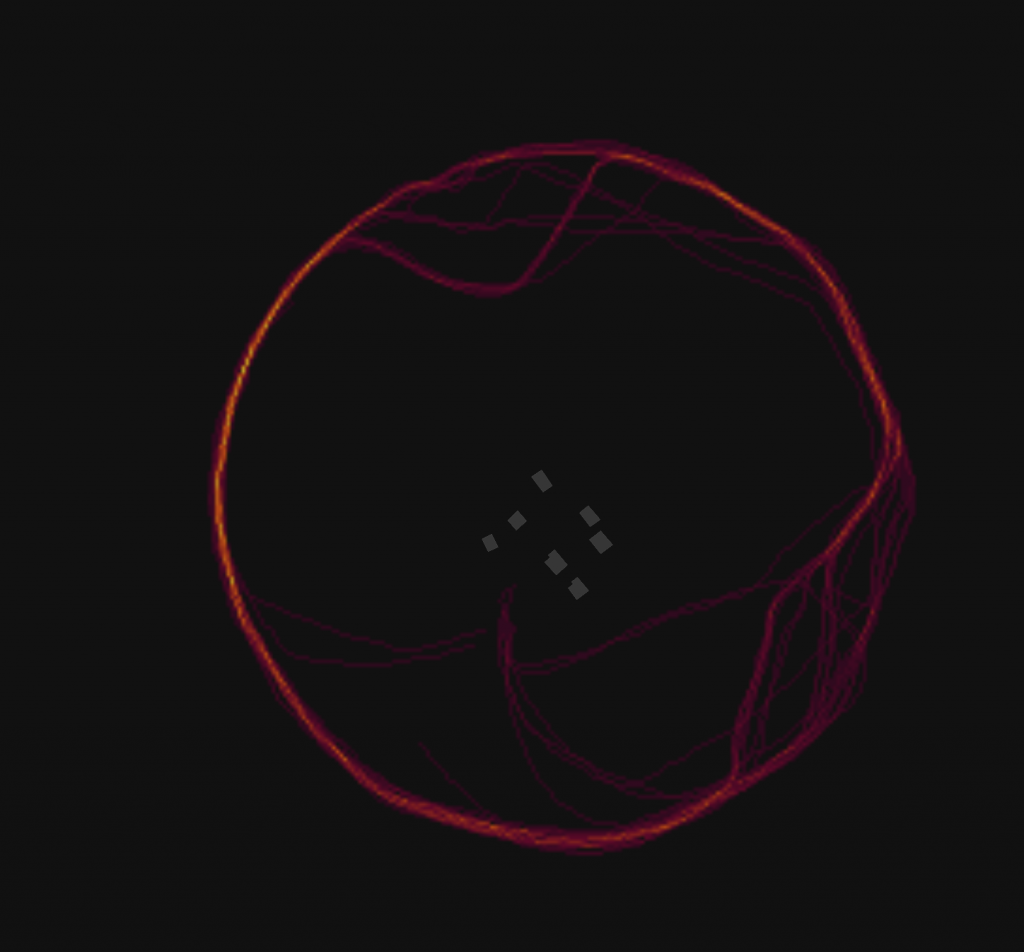

The post covers several categories of information that can be gleaned from examining Strava’s fitness tracker data, ranging from enabling the identification of secret military facilities in “dark areas” to specific identifiable behaviour patterns of at-risk individuals.

Scott-Railton refers to the kind of intelligence that can be collected by examining wearables as PAPI: Presence, Activity, Profile and Identification.

| Type of Signal | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Presence | In some cases, the presence of one or more individuals with trackers points to a non-public fact, such as the location of an installation. | A covert military outpost is identified by a consistent pattern of exercise activity in a remote area, or an area where there are few other users of fitness trackers. |

| Activity | Activity level at a sensitive installation can be ‘read’ based on volume of fitness tracker activity | Rate of activity of personnel at an embassy, or installation, can reveal important information about activities and strategy |

| Profile | A single fitness tracker user, or users, who regularly wear fitness trackers during their work activities can signal important information about who they are and what they are doing. | Patrol routes can be observed at a military base, or outside of a military base. |

| Identification | In areas of high fitness tracker use, it may be difficult to identify specific people; however, in areas where fitness tracking is less common, specific residences or other locations can be used to identify individuals | Individual homes or workplaces, as well as other uniquely identifying areas can be used to associate a particular trajectory with a particular individual or small group. |

This kind of information presents a clear threat to the operational security of governments and institutions, but the risks that it poses do not end there. Scott-Railton describes being able to identify individuals’ jogging routes from their homes and highlights the ways that such data could be used to stalk or commit violence.

The analysis makes it clear that, while Strava’s “God’s Eye View” is alarming, it is not unique. Not only do other fitness companies publish similar maps, but fitness trackers are designed to collect large amounts of information that many would consider sensitive and private.

Prior Citizen Lab Research on Fitness Trackers

In 2015-16, Citizen Lab researchers conducted a comprehensive experiment and analysis of fitness trackers. Researchers purchased and wore fitness trackers from a variety of manufacturers. After a period, the researchers requested that the companies send them the data that they collected. The researchers also examined the security and communications protocols used by the devices.

The results, published in Every Step You Fake: A Comparative Analysis of Fitness Tracker Privacy and Security. were alarming:

- Nearly every device studied bore a fixed Bluetooth MAC address, enabling persistent tracking

- Several applications sent precise geolocation information to remote servers when the user wasn’t working out

- Three applications sent sensitive health data over the Internet without proper transmission security, facilitating man-in-the-middle attacks and replay attacks

- What companies were technically measured to collect rarely corresponded to the data that people received when they requested their personal data from their fitness tracker

- The study led to two applications being updated to improve their data transmission security

Whose Fault?

Many observers have been quick to poke fun of the military personnel and others whose injudicious use of their fitness trackers exposed these confidential activities. However, we believe that the case reflects several major challenges around user privacy and data security that extend beyond wearables:

- Users are often unaware that the privacy settings enabling them to hide things from strangers do not extend to their privacy from the platform that they are using

- When privacy settings are presented as complicated opt-outs, users will often have trouble using all of the settings that are available to them to exercise those rights

- Location privacy can be difficult for users to fully understand, and many devices and apps are more convenient to leave running than to disable

- Oftentimes data presented as “anonymized” is anything but

- Companies that collect vast amounts of user data, such as fitness trackers, will invariably become attractive targets for government agencies and criminal organizations. Some governments may compel or coerce companies to turn over user data they collect making these companies effectively “proxies” for state surveillance and espionage. If user data is improperly secured, criminals who are able to acquire the data can employ it for all ranges of fraud and abuse

Strava, by releasing vast amounts of sensitive user data, has made it easier to illustrate the dangers posed by the vast amount of location information that we share with popular services. Most services that collect this kind of information have never, and likely will never, publicly display the extent of the data that they have collected. We hope that the Fit Leaks case will provide an opportunity for a conversation around location privacy and security.

Read more: Why Strava’s Fitness Tracking Should Really Worry You