Approaching Access

A Look at Consumer Personal Data Requests in Canada

Canadians can learn new things about your personal data by requesting access to it from companies. What can be found out varies by company and there can be some hurdles to overcome before you get access.

What Do Companies Know About You?

When you use your mobile phone, your geolocation can be recorded by your cell phone provider based on your phone’s proximity to the providers’ cell phone towers. Online dating applications may retain your personal messages and photos even after you think they been deleted. Fitness tracking companies can be subpoenaed to share statistics about your health and well-being in criminal proceedings. In an era when smartphones are ubiquitous, personal data may be collected, stored, and used in many unexpected ways– and few company statements and policies provide personalized answers about what they precisely do with that data.

Without knowing who is collecting your personal data, for what purpose, for how long, or the grounds under which they share it, you cannot exercise your rights nor evaluate whether a company is appropriately handling your data. Canada’s commercial privacy legislation, the Protection of Personal Information and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), empowers Canadians to issue legally-binding Data Access Requests (DARs) to private companies to answer these kinds of questions. Through a three year study of DARs in Canada we show what happens when telecommunication service providers (TSPs), fitness tracking services, and online dating companies are asked by consumers to provide transparency into their data practices and policies.

Between 2014-2016 we recruited participants to systematically issue DARs to 23 companies:

- Canadians TSPs: Fido, Koodo, NorthwestTel, Primus, Rogers, TekSavvy, Bell, Shaw, WIND.

- Fitness tracking services: Apple, Basis, Bellabeat, Fitbit, Garmin, Jawbone, Mio, Withings, Xiaomi.

- Online dating services: Bumble, Grindr, OkCupid, Tinder, Scruff.

What We Learned

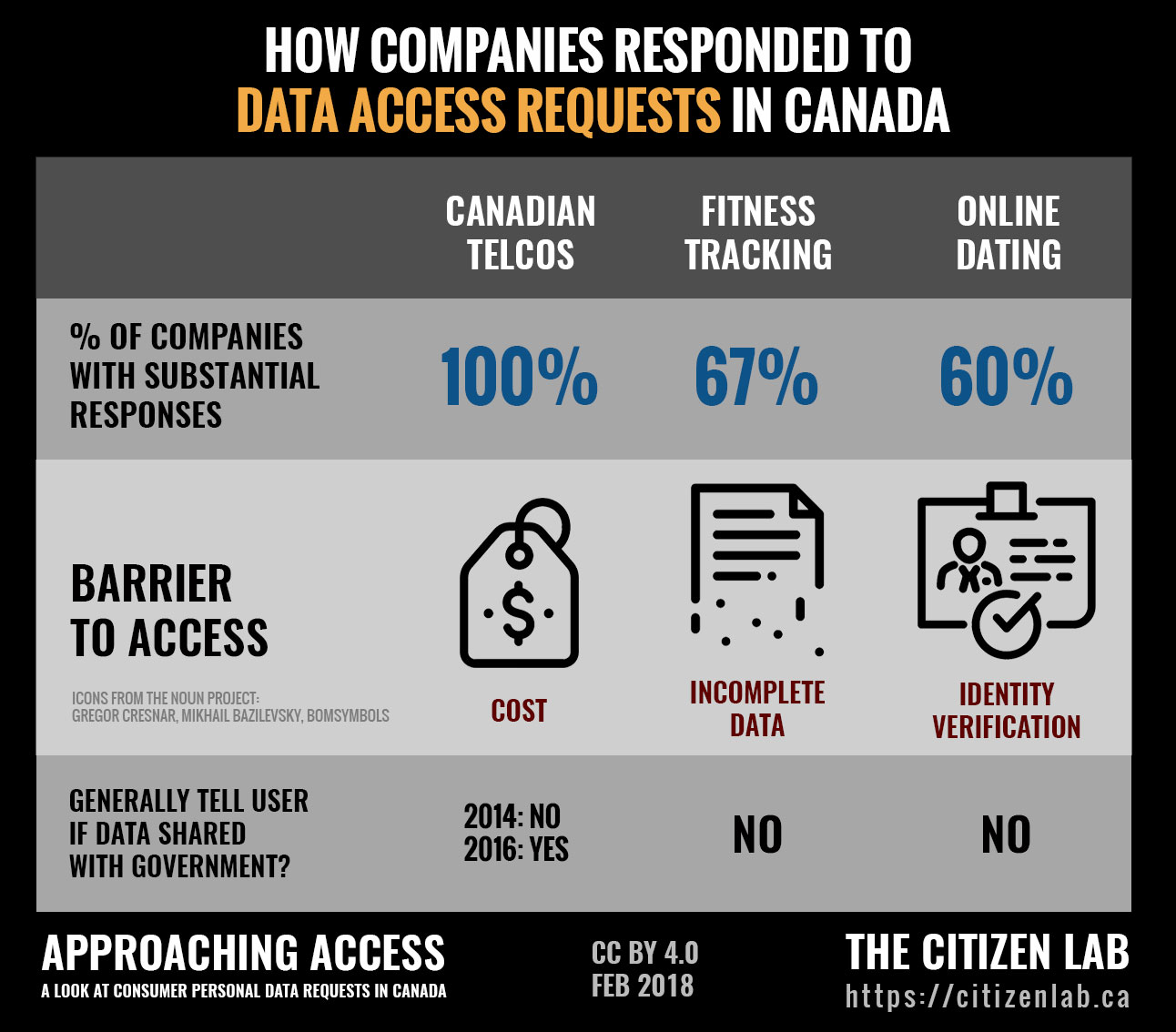

Participants encountered a range of barriers accessing complete copies of their data including costs charged for access, identity verification procedures, and data transmission procedures. The responses and data provided by companies also varied.

Telecommunications

- Barriers to Access: All TSPs charged participants a fee for access to detailed SMS or call records.

- Variation in Responses: In 2014 TSPs generally did not clearly tell participants if their data had been shared with third parties such as government agencies. In 2016, the majority of TSPs provided clear responses to the question of third party data sharing.

Fitness Tracking Services

- Barriers to Access: Several companies directed participants to data download tools. These tools are convenient and relatively secure, but did not include all requested data.

- Variation in Responses: Several fitness tracking companies did not respond at all to requests. Those that did respond either provided data via email or directed participants to data download tools.

Online Dating Services

- Barriers to Access: Identity verification was required to grant access to data.

- Variation in Responses: Data provided included messages, photos, and location history including photos users had deleted.

Our findings demonstrate that consumers sending in DARs can help encourage companies to be more transparent, that companies have several clear opportunities to improve how they handle DARs, and that regulators can provide valuable guidance to clarify company obligations around responding to DARs.

Full Report

This blog post is a summary of our research into DARs sent to companies in three industries. We highlight key findings for TSPs, fitness tracking applications, and online dating services.

For a broader discussion of these findings and a more detailed look at what data people can get back and what that means, please consult our full report.

1. The Right of Consumer Access

It can be challenging for consumers to figure out what data companies are collecting about them, how it is then used, or with whom it is shared. In Canada, consumer privacy law provides a way for consumers to learn more about how their data is handled. Canada’s commercial privacy laws, include a right of access; under such a right, companies are legally obligated to respond to an individual’s request for access to their own personal information that is held by the company.

In Canada, the federal Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) sets out the right of access. PIPEDA Section 4.9 obligates companies to respond to DARs within 30 days. The requested data should be made available to requesters at “free or minimal cost.”

Individuals can use DARs to better understand an organization’s privacy practices. Privacy policies are notoriously verbose and vague about what data is collected by organizations, or how that data is then used, whereas DARs are meant to help individuals obtain a more complete and accurate account of what data an organization retains about the requester and how that data is subsequently handled. However, across jurisdictions, few citizens know that they can create DARs or how to create such requests, and as a result DAR usage is relatively low. Even when individuals go through the trouble of submitting DARs, they often encounter barriers that hinder or prevent access to the requested information.

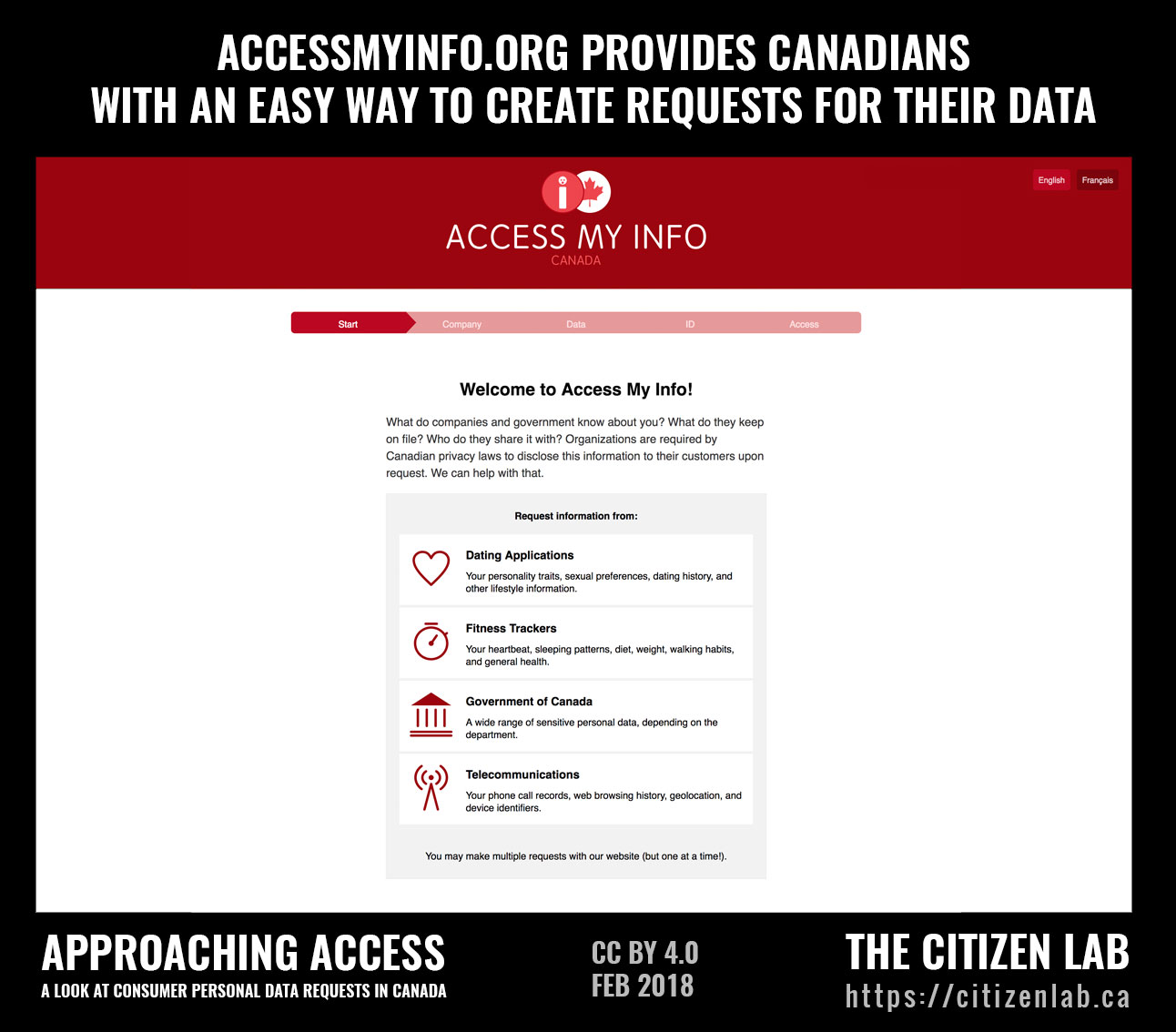

1.1 Access My Info

Since 2014, the Citizen Lab and its partners have operated Access My Info (AMI). AMI is a web application that makes it easier for Canadians to create DARs, following a semi-standardized template. As of February 2018, over 6,000 requests have been created using the application in Canada. AMI was originally part of the Citizen Lab’s Telecommunications Transparency project, and solely supported developing DARs to Canadian TSPs. Following a 2016 redesign, AMI now helps Canadians create DARs for fitness tracking companies, online dating applications, as well as requests to certain departments in the Government of Canada.

2. Data Sources

This report used primary data provided by research participants who had sent DARs to TSPs, fitness tracking services, and online dating services. Participants were drawn from a pool of AMI users who had opted-in to being contacted by our research team as well as a group of users who were recruited to use, and issue DARs to, fitness tracking services. The correspondence between our research participants and the companies they issued DARs to serve as the core of the data we analyze in this study.

Additionally, we repurposed DAR correspondence collected in previous Citizen Lab investigations into TSPs and fitness trackers. Those projects are described further in the next section.

3. Industry Background and Prior Work

This section describes our motivations for studying DAR responses from TSPs, fitness tracking applications, and online dating services. It also presents some of our previous work looking into the privacy and security of TSPs and fitness tracking applications.

3.1 Telecommunications Service Providers

Most Canadian households (85% as of 2016) have mobile phones, and TSPs operate the communications infrastructure that supports our phone calls, text messages, and much of the data transmitted to and from every app we use on our devices.

The Citizen Lab has extensively studied the relationship between TSPs and government agencies through its Telecommunications Transparency Project. In particular, the project has investigated what data, and under what legal conditions and oversight, can be provided by TSPs to government agencies. AMI was released under this project in 2014. The project and related efforts by Canadian privacy advocates has helped encourage Canadian TSPs to release corporate transparency reports detailing statistics on the data they share with government agencies.

We repurposed DAR correspondence data collected in our 2014 launch of AMI for the comparative analysis presented below. In addition, we collected a new data set in 2016 via AMI users.

3.2 Fitness Tracking Applications

Fitness trackers can collect data about a user’s heart rate, steps, calories burned, sleep patterns, height, weight, fitness goals, diet, and more. These data give users a window into their personal fitness. In some cases, users can share some of their fitness data over the Internet with their friends to compete, hold one another accountable, and congratulate one another on achieving fitness milestones.

In 2016, we released a report that studied fitness tracking applications from three different methodological approaches: technical analysis, policy analysis, and DAR correspondence analysis. Our report found that these three methods, when used together, can reveal more information about a company’s data practices than any one method alone.

We reused the DAR correspondence data collected in our 2015-16 fitness tracker study for the comparative analysis presented below.

3.3 Online Dating Services

Users of online dating applications upload intimate photos, messages, and profile details to online dating services’ servers. The services use these data to present users with potential matches by assessing a variety of variables such as location, stated preferences, age, gender, and sexual orientation. The privacy interest in dating applications is clear: a 2014 Pew Research Centre survey found that 71% of Americans regard their relationship history as very or somewhat sensitive data. A 2016 security analysis of several popular dating applications found many instances of GPS coordinate leaking, insecure photo transmission, and potential for account compromise.

We collected DAR correspondence from AMI users who had submitted requests in 2016 to online dating companies for the comparative analysis presented below.

4. Analysis of Company Responses

This section presents our analysis of DAR correspondence within each of our studied industries: TSPs, fitness tracking applications, and online dating services. For each industry, we evaluate responses our participants got to questions in their DARs, as well as any difficulties involved in getting those answers. We highlight notable types of data that our participants received, and what sort of insights can be derived from those data. A comprehensive discussion of each industry can be found in our full report here [PDF].

| Year | Industry | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Telecommunications | 6 |

| 2015-16 | Fitness tracking applications | 8 |

| 2016 | Telecommunications | 5 |

| 2016 | Online dating services | 5 |

Overview of research participants across industries

The DARs our participants sent each followed a template that we developed for each industry. The template lets participants select the kinds of questions, and associated data types, they would like the given company to respond to. For example, the letters asked whether the company had provided the requester’s data to third parties or government agencies. Letters also asked for metadata such as IP address logs, geolocation, photos, and health data. Participants sent letters with slightly different questions and data types for different industries (Copies of the templates are available in Appendix A in the full report). After selecting these questions, and inputting personal information that is designed to help the company respond to the questions, the AMI web application populates the DAR template using the responses to these questions. The end result is the participant receives a customized DAR that they can then send to the given company.

4.1 Telecommunications

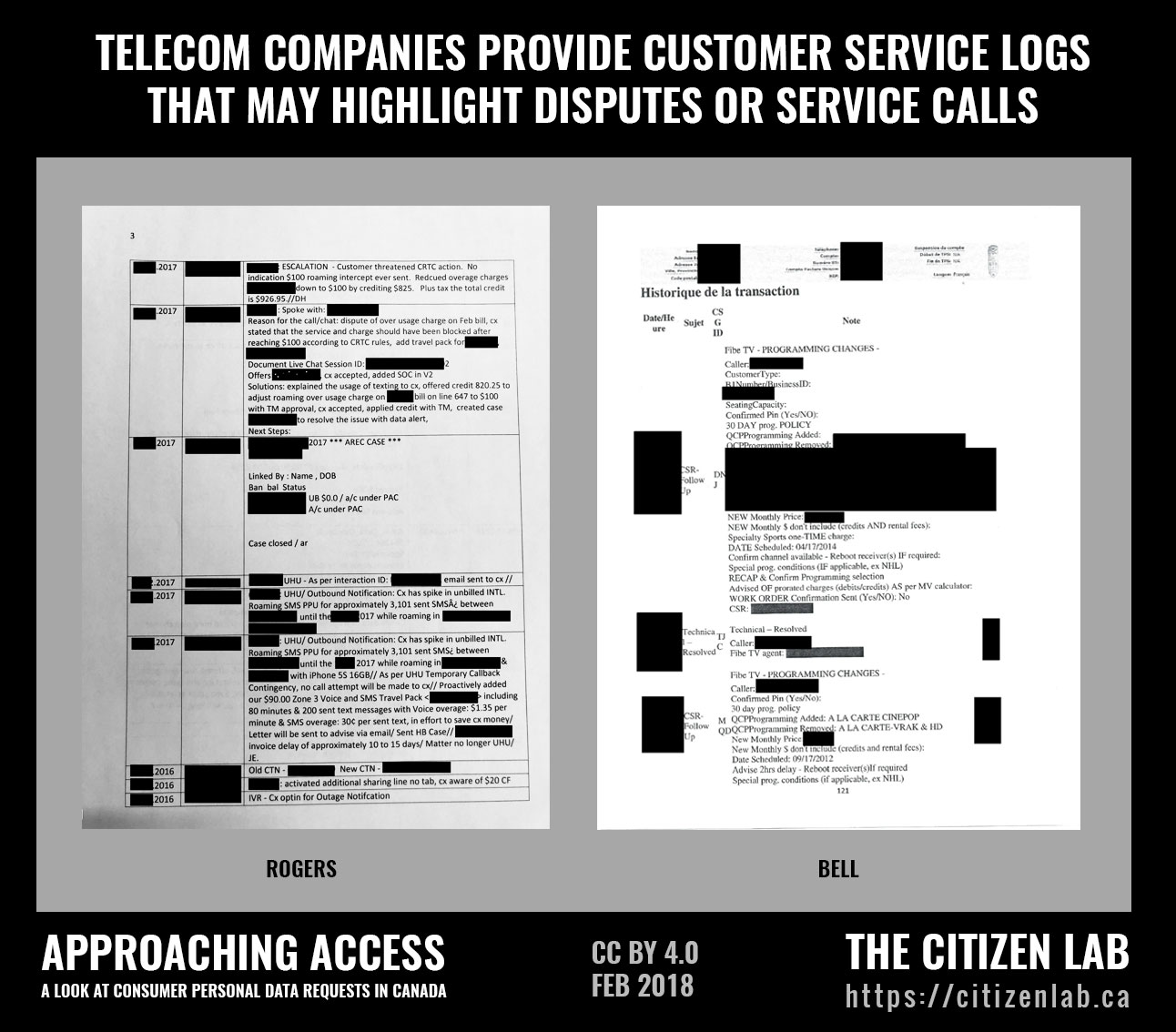

Most TSPs responded to DARs with cover letters that were intended to address some of the questions asked of them. Some companies also provided a longer letter or response to the questions asked which included some of the requested data.

TSPs generally provided clear answers about whether or not a participant’s data had been previously disclosed to government agencies or law enforcement. However, our participants encountered barriers in their attempts to obtain access to detailed technical metadata retained by TSPs.

| Year | Companies |

|---|---|

| 2014 | Fido, Koodo, NorthwestTel, Primus, Rogers, TekSavvy |

| 2016 | Bell, Fido, Rogers, Shaw, WIND |

Overview of our sample of TSPs that were sent DARs

Getting Answers

Disclosures to Government Agencies

In 2014 DAR responses, only TekSavvy clearly stated whether or not personal data had been disclosed to government agencies. Other TSPs in our sample cited section 9 (2.1) of PIPEDA, which establishes a process for notifying government institutions in the event of a request for information about disclosures of personal information to government institutions, or made statements about being unable to provide an affirmative or negative response without first consulting with government agencies.

In 2016 DAR responses, Fido, Rogers, and WIND were clear in their initial response about whether or not the participants’ data had been disclosed to government agencies. Shaw responded with what might have been a typo, stating they could “confirm that your personal information has or has not been released to a government agency,” but otherwise did not raise any issues with responding to the question. Bell responded with a less direct answer, stating that it would have to notify government agencies about the request and provide an answer to the participant within 30 days. Bell justified this delay by citing section 9 (2.1) of PIPEDA. We did not receive data from our participant regarding whether Bell ultimately responded to this question. WIND also mentioned its obligation to comply with section 9 (2.1) but, in the next sentence of its response, stated that no requests from law enforcement had been made about our participant.

Collection of Geolocation Data

Bell and Fido / Rogers both stated that geolocation information is not collected unless the customer sends or receives a call or text message. WIND responded that they would collect location information in the instance of either an e911 call or government agency request to track a person’s phone using GPS. Koodo stated that they may be able to track the geolocation of a customer’s phone in real time in order to assist service providers in locating a customer’s device or in response to a court order.

Data Received

The data TSPs generally provided in their initial responses (without cost to the participant) were customer service interaction records in hard copy or PDF format. These records described the time, date, and nature of a participant’s interactions with their TSP’s customer service departments. Figure 2 provides an example of customer service interaction logs that were provided to a participant by Rogers. Companies often suggested that their subscribers could obtain some of the other data types being requested from online customer service portals, where they could review previous invoices, or to an online tool where they could determine their current IP address.

Regarding assigned IP addresses, call log details, and SMS / MMS metadata, TSPs almost uniformly informed participants that they could access this information if they paid a fee. Participants were instructed to provide a time range for the requested data, after which the TSP would respond with a cost estimate. Only one of our participants (requesting data from Fido) decided to pay the fee to obtain some of the requested information.

| TSP | Type of data | Price quoted |

|---|---|---|

| Fido | Detailed SMS and call record data including cell tower information | $100 per month |

| Rogers | Call logs beyond 18 months old | $15 per month |

| Shaw | IP addresses historically assigned | $250 per year per modem |

| Shaw | Archived outgoing call records | $250 per telephone number per year |

| Bell | IP addresses historically assigned | Bell said they would provide a cost estimate if participant provided a time period. The participant did not follow up. |

| Koodo (2014) | IP addresses historically assigned | 60 hours at $20/hour (totalling $1,200) for all historical records |

| Primus (2014) | IP addresses assigned historically | 1 year of IP addresses provided at no cost |

Notable price demands by TSPs for access to specific personal data. Data from 2016 unless indicated

The participant who followed up with Fido dealt with the Rogers legal department (Rogers is the parent company of FIDO). Rogers charged the participant a fee of $100 + HST for one month of call and SMS records, and $100 + HST for one month of cell tower connection details. All call logs and SMS records were timestamped and associated with a cell tower ID. An accompanying document linked the cell tower IDs with physical addresses. This data was all provided in PDF files.

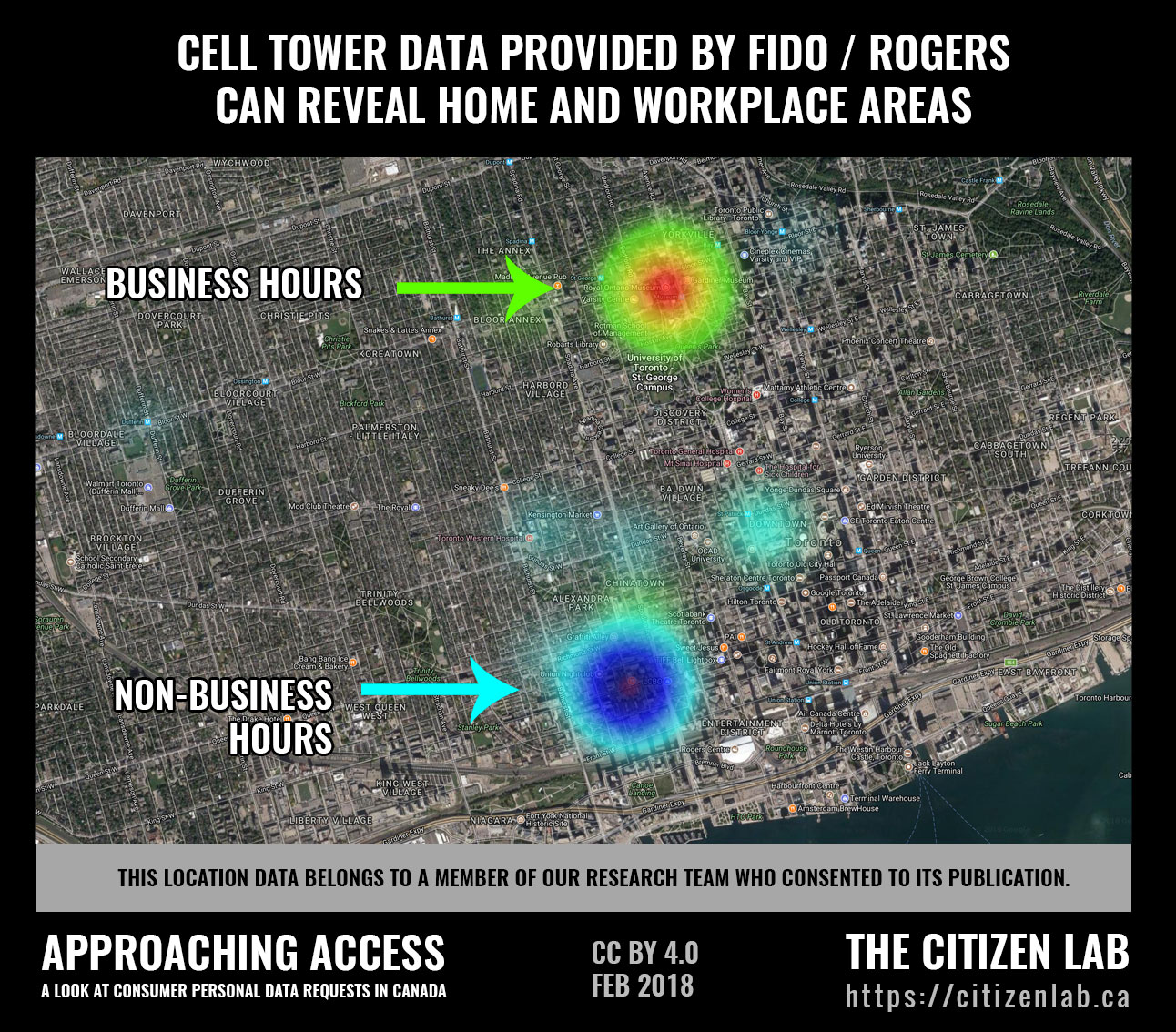

Visualizing Cell Tower Connections

We created a visualization to demonstrate the significance of the the cell tower data provided by Fido / Rogers. We took the provided PDFs, built a spreadsheet, and then wrote a python program to associate each phone call and text message with the address of the connected cell tower, which let us plot those locations on a heat map. The data was separated into two categories: data points placed outside of business hours and during business hours. The map, pictured below, paints a clear picture of where the participant works and lives. The participant in this case is a member of our research team, who has chosen to illustrate their data to help convey the significance of cellular metadata.

4.2 Fitness Tracking Applications

Our participants sent DARs to nine fitness tracking application companies; only six responded. Companies communicated with participants over email and responded to questions posed in the DARs. All responsive companies required some form of identity verification and secure data transmission before providing detailed records.

Several fitness tracking applications provided participants with instructions on how to access their data through data download tools that were located in the companies’ respective online user account portal. These data download tools are a user-friendly and secure method of providing access to data. However, in our sample the downloaded data were incomplete and did not include user profile information nor detailed metadata about application usage.

Fitness tracking companies in our 2015-16 sample included:

- Apple

- Basis

- Bellabeat

- Fitbit

- Garmin (no response)

- Jawbone

- Mio (no response)

- Withings

- Xiaomi (no substantive response)

Getting Answers

Fitness tracking companies used different techniques to securely transmit data to our participants. In the case of Basis, the data transmission process proved to be a barrier for our participant. With Fitbit, our participant had to engage in some back and forth with the company to determine a simple and secure transmission method. These cases are discussed in detail below.

Apple verified the identity of our participant by asking several questions about the participant’s personal and account information. The data was transmitted by email after Apple verified our participant’s identity. Two emails were sent: the first contained a password-protected file and the second included the password to the file.

Basis’ process for sending data was also via email. In order to transmit the data more securely than plaintext email, the company asked our participant to use PGP mail encryption and respond to the company with their public encryption key. Our participant did not know what PGP encryption was and did not install PGP on their computer. The participant was therefore unable to provide a public key to Basis and did not receive any data.

Fitbit verified our participant’s identity by checking their email address against their user account and asking for the approximate date on which they first paired their Fitbit with their device. Fitbit informed the participant that it was “unable to deliver your information in a non-secure format.” They provided two options for transmission: a password-protected zip file or a Google Drive upload shared with the participant. The participant chose the Google Drive option.

Jawbone and Withings directed our participants to the data export tools they provided through the participant’s existing online accounts.

Data Received

Participants received data as either prepared data disclosures (Apple and Fitbit) or were directed to data export tools (Basis and Bellabeat). The data exports were generally less comprehensive than the prepared data dumps. Basis and Bellabeat did not provide any data beyond a written response to the DARs they received.

Prepared Data Disclosures

Apple provided a spreadsheet that listed the participant’s name, postal address, iTunes purchase history, logs of IP addresses associated with various events, and many other data points. However, Apple did not include any fitness information. In its DAR response, Apple stated that it does not offer a fitness tracker, and inferred the participant may be inquiring about the Apple Watch. Apple’s response linked to Apple’s Approach to Privacy that explains that all Apple Watch data is encrypted locally and cannot be read by Apple. Apple did not provide any encrypted records to our participant (who had turned on Health data iCloud backups).

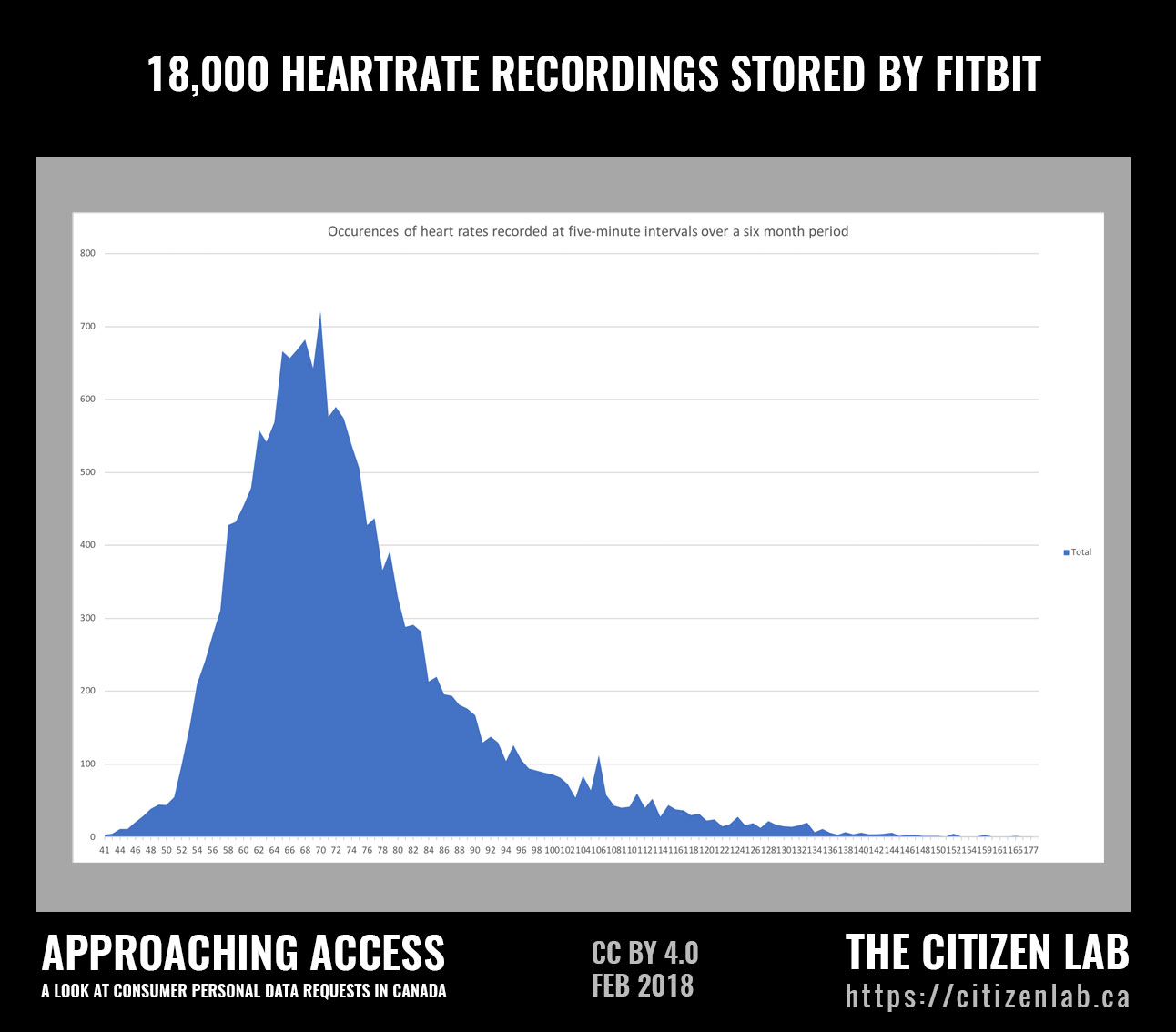

Fitbit provided a spreadsheet that included user email, birthdate, date of first device pairing, friend count, gender, sleep start and end times, weight, and over 18,000 heart rate records created at five-minute intervals throughout the six-month period that our participant had used the application.

Visualizing Heartbeats

We plotted the heart rate data provided by Fitbit in Figure 4. The graph depicts how frequently a particular heart rate occurred, and provides a glimpse of our participant’s normal heart rate distribution. The participant in this case is a member of our research team and has given full consent for this data to be displayed.

Fitbit’s spreadsheet also included IP addresses associated with timestamps. Multiple IP address records were present for individual days, indicating that one IP address log may be associated with one usage session of the app. The earliest IP address data occurred on the date the participant first paired their device with the app, indicating that IP addresses are retained for a period greater than the six months our participant had been using their Fitbit, and potentially indefinitely.

Data Export Tools

Through data export tools Jawbone and Withings provided spreadsheets that included step counts, calories burned, weight, distance, and other fitness metrics, organized by date. The format was similar to the data provided by Fitbit. Withings also included blood pressure while Jawbone included mood and mealtimes. These data exports did not include user account information nor IP address logs, suggesting they may not represent a complete record of the data retained by the companies.

4.3 Online Dating

All but one online dating company in our sample responded to our requests. One responsive company did not answer any questions and instead instructed our participant to fill out a form before proceeding with the request.

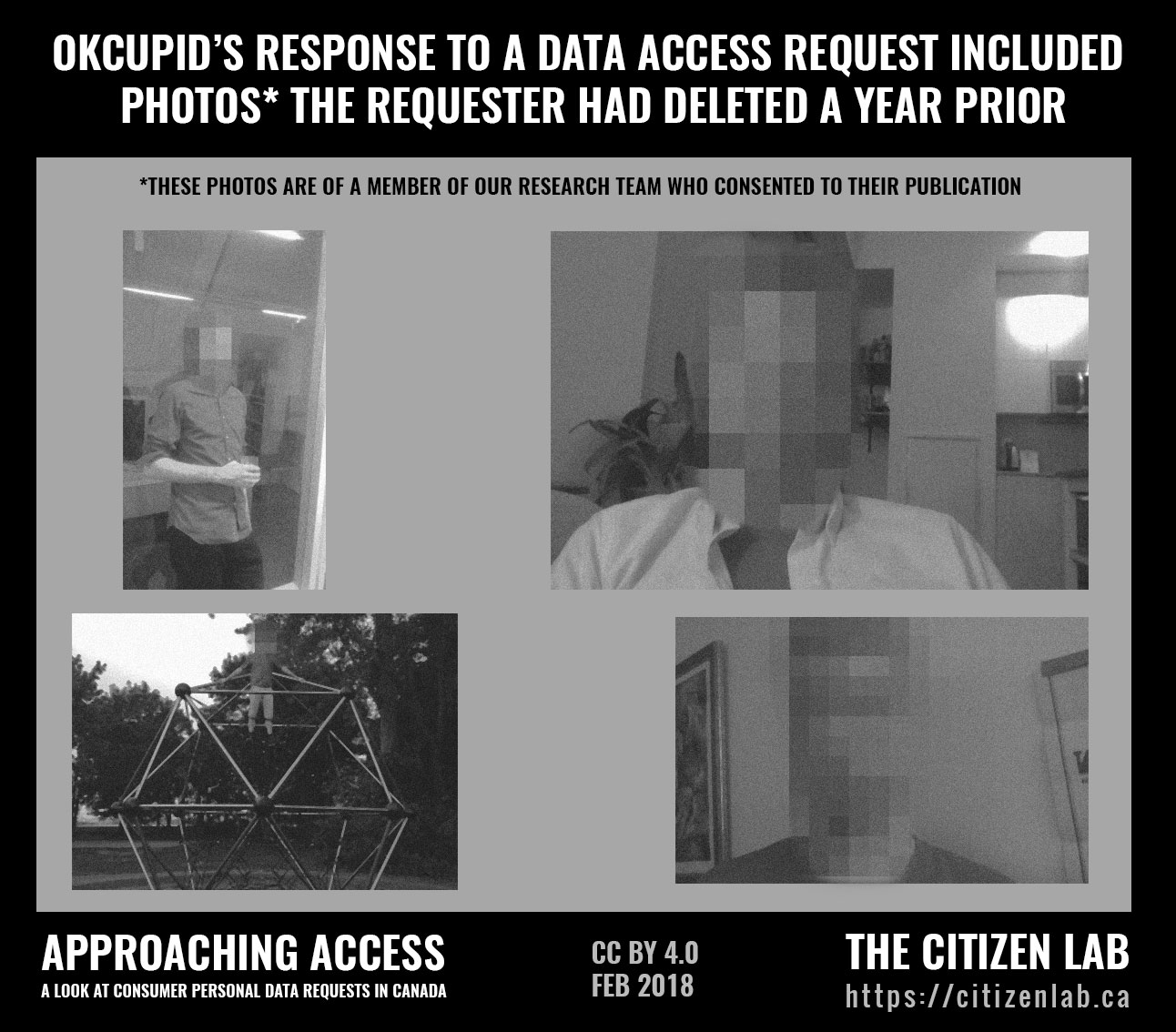

Requests to online dating companies, all of which were based in the United States, revealed that companies were often reticent to explicitly acknowledge their legal obligation to comply with PIPEDA. Only one participant (requesting data from OKCupid) followed through with identity verification steps needed to obtain access to their data. The participant received a dataset including messages, photos, and location history once they verified their identity with OkCupid. The dataset included photos the users had deleted and believed were no longer retained.

Online dating companies in our 2016 sample included are as follows:

- Bumble

- Grindr

- OkCupid

- Tinder

- Scruff (no response)

Getting Answers

Jurisdiction

All of the online dating companies included in our sample are based in the United States. Several of our participants who issued DARs to online dating companies received responses that highlighted this difference in jurisdiction.

Bumble sent our participant a form they had to fill out before data would be released; that form was designed to comply with European Union data requests. None of the questions asked in the letter were answered by Bumble. The participant chose not to fill out the provided form and never received data from Bumble.

OkCupid and Tinder are both owned by Match.com and responded identically to our participants’ DAR requests. They provided responses to each question asked, with the exception of the question that requested access to all of the participants’ personal data that was held by the company. The companies asserted that most of the participant’s personal information could be accessed through the applications themselves. They furthermore stated:

“You should be aware that, even if PIPEDA applied to [Tinder or OkCupid], this legislation only provides a right of access. PIPEDA does not require organizations to provide you with copies of your personal information if you can otherwise access it.” – OKCupid Privacy Officer, personal communication with research participant, July 1, 2016.

This statement is worded in such a way that Tinder or OkCupid’s commitment to comply with PIPEDA is left ambiguous. Nevertheless, the companies stated they would provide access to data not available in the user interface if the participant verified their identity.

Grindr responded by stating that it required a search warrant or subpoena to provide access to a user’s data. PIPEDA was not mentioned in its response.1

All companies with a real and substantial connection to Canada are required to comply with PIPEDA and Canadian courts have issued rulings to that effect.

Identity Verification

The Match.com companies OKCupid and Tinder asked our participants to verify their identities with the companies prior to providing any copies of personal data. The requests to the companies were sent using the email addresses associated with their Tinder and OkCupid accounts. To verify their identities, the companies asked our participants to provide a “notarized copy of your driver’s license or passport” via postal mail to a P.O. box in Dallas, Texas, where Match.com is headquartered in Dallas.

Our participant requesting data from Tinder did not follow through with this identity verification process. Our OkCupid participant choose to send the company a redacted photograph of their driver’s license and returned the image to the company over email.

OkCupid accepted this form of identity verification, which was less time- consuming and potentially expensive than having a document notarized and mailed to Texas.

Data Received

OKCupid represents the sole online dating company for which our participants received a data attachment. It is unclear what data Tinder and Bumble would have provided had our participants completed the steps asked of them by the companies.

The data provided by OKCupid was a large password-protected PDF file that included basic account details (username, password hash, age, gender, saved search parameters, and several other fields).

The OKCupid PDFs we analyzed also included timestamped records of IP addresses and relatively precise geolocation. IP addresses were provided under the heading “Login history”, therefore appearing to have been collected upon user login. Multiple geolocation records per day were visible, indicating the records may have similarly been created at the beginning of a new usage session of the mobile application. The records stretched back to the date our participants first began using OkCupid, indicating that the IP addresses and geolocation logs may be retained indefinitely.

The OKCupid data also included photographs the participants had uploaded to their profile. In another case of apparent indefinite retention, the company also included photographs that a participant had deleted through OKCupid’s web interface. These photographs were flagged as [inactive] in the provided data. Each provided photograph (“inactive” or not) was accompanied by OKCupid CDN (Content Delivery Network) URLs that hosted live versions of the photographs.

These URLs remained active although the participant had deactivated their account over a year before issuing the DAR request.

5. Barriers to Access and Recommendations

Across each industry we looked at, barriers often prevented participants from continuing with their requests and accessing complete copies of their data. The price of access for detailed records deterred most of our TSP requesters from getting full access. Identity verification presented a hurdle for some online dating participants, and a security process prevented a participant from getting their fitness data.

5.1 Price of Access

Participants who issued DARs to TSPs were usually informed they would only receive all of the data they requested after paying a fee. This requirement led to DAR participants only obtaining a subset of the data they requested in their DARs, with those who declined to pay a fee typically not receiving detailed geolocation-related information and, in some cases, logs of historically assigned IP addresses. These records can be considered metadata — data about calls that took place, or data about Internet connectivity. While this metadata may be considered fairly technical and pertain to cell towers and routers, we used this data to paint a fairly compelling pattern of life of one of our research member’s movements throughout a month. Unfortunately, most of our TSP participants did not pursue access to these metadata when confronted with the price tag.

Recommendation:

Companies should refrain from charging fees for access to personal information following the spirit of PIPEDA that access should be provided at free or minimal cost. In our sample, a TSP DAR response that includes a price for further access typically serves to halt the request. While companies may not intend to stop a request in its tracks by introducing such costs, they could reduce their own costs by improving internal processes that facilitate the compilation of all customer personal data, including detailed technical metadata. Alternately, they might provide a sample of records to reveal the kinds of data and metadata which are collected and then only enter into a fee negotiation if the effort to provide additional data would require expensive manual intervention.

5.2 Capacity to Understand Data

Even if access to TSP cell tower and IP address data were granted free of charge, many requesters may not have the expertise to appreciate the significance of the revealed technical metadata, leaving them unable to appreciate the meaning and context of the provided information. For instance, the analysis we undertook on the retrieved cell tower information in Section 4.1 required a degree of time and skill that average consumers may not have.

Recommendation:

Companies should provide access to personal data in a usable format. Data that includes rows and columns should be provided as a CSV file or other open format. Companies should not provide any textual or numeric data in an image format, such as a screenshot or image-based PDF. Text and numbers should be easily searchable, selectable, and easy to copy.

People who issue DARs may benefit from tool support that can help them to better make sense of the data they get back. Companies could offer tools that facilitate the analysis of data retrieved through DARs. Alternatively (or in tandem) public interest groups and individuals could develop similar tools (any third party tool should not collect any personal information, and instead process any data locally on a user’s device).

5.3 Secure Transmission

Several companies sent data to our participants over email without using any sort of additional security. Email by itself does not offer strong security protections. Apple, OkCupid, and Tinder all sent data over email in the form of an encrypted zip file, and sent the password for that zip file in a separate email. Basis proposed a high level of security to our participant through PGP mail encryption. However, research has shown that PGP is challenging for many people to download, install, and operate. Basis’ requirement that its users use PGP served as a barrier to our participant, who was unable to receive their data.

Several fitness tracking companies directed our participants to data download tools. Such tools offer a convenient and relatively secure way to access the personal data held by a company. However, in our sample, we found these data downloads were not as extensive as those provided by companies that sent data directly to participants. In particular, data export tools did not include the breadth of metadata that was provided by companies which directly sent data to individuals.

Recommendation:

Companies should offer strong security protections when transmitting personal data in response to a DAR. The requester should not have to undertake significant additional effort as a result of these security mechanisms. Companies should offer data download tools that are accessible through their existing online user portals. In their DAR responses, companies should respond to any questions asked of them and direct requesters to their data download tool.

These data export tools should provide complete access to all personal data retained about the user, including data such as access logs, location history, analytics records, account status history, and customer service interactions. The data download should be conducted over an encrypted channel. Data should be provided in a usable format. The downloaded data should be accompanied by a data dictionary that describes the meaning and context of all provided data.

5.4 Jurisdiction

In our sample, online dating companies raised the most issues about providing data in response to a request citing Canadian law. OkCupid and Tinder demonstrated a willingness to provide data, but also made statements that cast doubt on their legal obligation to respond. Grindr did not provide data when one of our participants sent a request in 2016 on the basis that the company required a (U.S.) subpoena to disclose personal data.1

Bumble responded to a request by asking a requester to fill out a form designed for compliance with EU data protection regulations. Our participant did not fill out the form which meant they did not receive their data from the company.

Recommendation:

Non-Canadian companies may need to be reminded about their obligations to comply with PIPEDA. This burden should not be placed upon requesters and is perhaps better suited to be included in outreach efforts undertaken by the federal Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (OPC).

Companies should provide complete data upon receipt of a DAR and any necessary identity verification and security measures have taken place. Companies should not require requesters to complete company-provided forms to obtain access and should, instead, directly respond to and engage with the substance of the DAR they receive.

6. Conclusion

When consumers exercise their right of access they show companies that there is market demand for greater data transparency. Our research suggests that DARs played a role in the TSP industry’s shift between 2014 and 2016, where they now generally inform requesters if their data has been disclosed to government agencies or law enforcement. Across industries, much of the data we analyzed was in an unstructured format that would be challenging for average consumers to fully understand, which highlights the need for consumers to have access to easy to use data analysis tools to make sense of often technical datasets. Our unexpected finding that OkCupid appeared to retain data seemingly indefinitely at the times we made requests suggests that DARs can provide insights to consumers about how their data is used, processed, or retained beyond what they can learn from just reviewing their data within an app.

The price of access barrier we documented presents an opportunity for the OPC to provide guidance regarding what constitutes “minimal” costs for access. PIPEDA does not provide clear guidance and, without clarity, arguably enables TSPs to charge high fees for access to sensitive metadata about their customers. While these fees may seem minimal and reasonable when compared against costs charged to government agencies making the same requests they nevertheless act as a disincentive to average customers. Guidance could help cap fees for access to help ensure that wealth has little bearing in who can fully exercise their rights.

Our look at online dating companies revealed that several US-based companies either suggest that PIPEDA might not compel them to respond to a request for access, or direct requesters to company forms they must fill out. Significantly, these forms that can constrain the parameters of a request for access. The OPC could help clarify company obligations by issuing guidance directed at non-Canadian entities and which outlines such companies’ responsibilities to respond to DARs, as well as whether or not companies can compel requesters to complete standardized DAR forms instead of submitting a written request for access.

Responding to DARs provides companies with opportunities to demonstrate their company’s commitment to protecting user privacy The barriers to access that we outline in our report — cost of access, data usability, identity verification, and secure transmission — along with our recommendations to mitigate those barriers, should interest to companies looking to improve how they respond to DARs. A comprehensive response to a DAR can currently set one company well apart from their competitors, though we would hope that in the future all companies would simply provide comprehensive accounts to customers who produce and issue DARs.

Given that companies collect, process, and disclose huge amounts of personal information pertaining to their users and subscribers, it is imperative that these same companies improve their existing privacy, transparency, and accountability processes. Data Access Requests are a way of obtaining additional clarity about what information a company retains and what it does with that information. However, barriers to access and the prevalence of incomplete responses highlight the fact that other accountability mechanisms, such as strong consumer privacy regulation, technical investigations, and robust corporate transparency reports, are all needed to raise the bar of consumer data protection.

Footnotes

[1] In December 2017, we received DAR correspondence between a requester and Grindr. In this correspondence, Grindr did provide data upon request. This correspondence is out of scope of this analysis, but warrants a mention to ensure Grindr is not misrepresented.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Adam Senft and Bram Abramson for review and copyediting. We are grateful to Ron Deibert for research guidance and supervision. This research would not have been possible without the Access My Info users and members of the Citizen Lab team who consented to participate in this study.

This report has benefited from financial contributions from the Canadian Internet Registry Authority’s Community Investment Program as well as the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s Contributions Program.