Access My Info

Measuring Data Access Rights Around the World

This report presents results from a series of research projects that measured responses to personal data requests from telecommunication companies and Internet Service Providers across jurisdictions in Asia including Australia, Hong Kong, South Korea, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Overall, the projects found responses from telecoms were incomplete and in some cases did not follow what is required by law.

Summary

How do the companies that provide the services we use to connect online and communicate handle our personal data?

What types of data do they collect?

How long do they retain it for?

Do they share it with any third parties?

Without knowing who is collecting personal data, for what purpose, or for how long, or the grounds under which they share it, a consumer cannot exercise their rights nor evaluate whether a company is appropriately handling their data.

As of 2019, 134 countries around the world have enacted data protection laws. A primary right under many data protection regimes is data access requests (DARs) which are written queries that an individual sends to a private company whose products or services the individual uses. DARs ask that company to disclose all of the data and information that the company holds on that individual, including when, how, to whom, and for what reasons a company shares or discloses the individual’s data, and other details about the company’s data protection practices and compliance with applicable privacy laws. Although the right to make DARs is part of many data protection laws in theory there is limited empirical documentation of how companies respond to these requests in practice.

In 2014, the Citizen Lab and Open Effect started Access My Info (AMI) a research project that uses data access requests and complementary policy, legal, and technical methods to learn about how private companies collect, retain, process, and disclose individuals’ personal data. Accompanying the research methodology is a web-based tool that helps members of the public generate data access requests based on templates tailored to different industries.

AMI was first applied in Canada and resulted in tens of thousands of Canadians making DARs to telecommunication companies. The results of the study showed inconsistent responses across companies and documented consumers experiencing in significant barriers to accessing their data.

Following the first AMI project in Canada, the Citizen Lab formed a working group to bring the research method to Asia and comparatively measure responses to DARs across the region. The working group includes academics, lawyers, advocates, and designers working in five jurisdictions:

🇭🇰Hong Kong: Lokman Tsui (Chinese University of Hong Kong), Stuart Hargraves (Chinese University of Hong Kong), Keyboard Frontline (advocacy organization, Hong Kong), InMedia (media group, Hong Kong), Jason Li (Designer, Hong Kong)

🇰🇷South Korea: Kelly Kim (OpenNet Korea), KS Park (Korea University)

🇦🇺Australia: Adam Molnar (University of Waterloo / Deakin University)

🇮🇩Indonesia: Sinta Dewi Rosadi (University of Padjadjaran)

🇲🇾Malaysia: Sonny Zulhuda (International Islamic University Malaysia)

Each partner sent data access requests to telecommunication companies and Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in their respective jurisdictions to better understand the type of data these companies collect on their customers, how long this data is retained for, and if it is shared with third-parties. Partners also sought to learn the methods by which these companies responded to requests: how long requests took to be fulfilled and the amount of work required on the part of the requester, as well as if and how fees for access are obtained.

While each jurisdiction has unique laws and context we found general patterns across them.

Data Protection in Asia is a Dynamic Legal Space: Asia is a particularly interesting region to conduct this study because it includes countries with strong personal data access laws and those with none or that are in the process of establishing data protection legislation. A commonality across all jurisdictions is that elements of data protection are in flux or subjects of debate.

While South Korea has the strongest data protection laws in the region, the AMI project found superficial compliance to DARs from telecommunication companies. All companies had online data request procedures, but the majority of companies only provided copies of their privacy policies in response to the data access requests. In response AMI partner Open Net Korea filed a lawsuit against Korea Telecom for not providing a complete response to DARs

In Hong Kong and Australia defining what is personal data has raised debate. In Hong Kong telecommunication companies and ISPs argue that Internet Protocol (IP) addresses and geolocation records are not personal data and therefore they are not required to give user access to this data. In Australia IP addresses are currently not included in the legal definition of personal information.

Other jurisdictions with emerging or non-existent data protection laws faced other challenges. Malaysia has established a data protection law, but it is not robustly enforced; Indonesia has a draft data protection bill but has not yet passed it into legislation. As a result in both jurisdictions DARs resulted in limited responses from companies.

Responses From Telecoms Across Jurisdictions Have Been Inconsistent With What Was Requested and In Some Cases What Is Required by Law: Overall, we found that responses from telecoms were incomplete and in some cases did not follow what is required by law. Generally, across the different jurisdictions we find that telecoms have yet to develop a mature process to fulsomely handle requests for personal data. These results show the importance of measuring how laws function in practice, rather than only reviewing what they mandate on paper.

This report provides results from each Asian jurisdiction as a series of case studies. We also include a summary of results from Canada (the first jurisdiction AMI was applied in) for comparative purposes.

Canada

Christopher Parsons (Citizen Lab, University of Toronto)

Key Findings

- Barriers to Access: All telecommunications companies charged participants a fee for access to detailed SMS or call records.

- Variation in Responses: Previous research showed that telecommunications companies generally did not clearly tell participants if their data had been shared with third parties such as government agencies. In 2016, the majority of these companies provided clear responses to the question of third party data sharing.

Background

Canadian telecommunications companies’ collection and use of personal data is regulated by a federal law, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). The law is centred around ten fair information principles:

- Accountability

- Identifying Purposes

- Consent

- Limiting Collection

- Limiting Use, Disclosure, and Retention

- Accuracy

- Safeguards

- Openness

- Individual Access

- Challenging Compliance

Organizations that collect personal data must have an employee responsible for compliance with PIPEDA. Such employees must identify the purposes for which information is collected, prior to the collection occurring, and any collection may only take place with the knowledge and informed consent of the data subject. Data collection activities should be minimized to that which is needed to accomplish a specific task. Data should only be used or disclosed for the purposes it was collected for and if it is no longer needed it should cease being retained. Data must be accurate and up-to-date, and protected by strong policy and technical safeguards. Companies must publicize documents describing their privacy practices and provide data to consumers upon request. Finally, consumers can challenge companies if they believe the companies have insufficiently complied with the law.

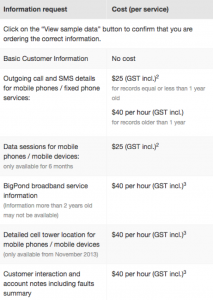

Table 1 provides an overview of how the principle of access to consumer data functions in the Canadian context:

| Legal Justification | Principle 4.9 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (2000) |

|---|---|

| Phrasing | “Upon request, an individual shall be informed of the existence, use, and disclosure of his or her personal information and shall be given access to that information” |

| Response deadline | 30 days, with a 30 day extension possible |

| Fee for access | “At minimal or no cost to the individual” |

| Remedies if unsatisfied with response? | An individual may file with the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada a written complaint against an organization |

Overview of Canadian law about data access requests

The Canadian telecommunications market is composed of several large incumbent companies as well as many much smaller competitive companies. There are little to no international companies offering competing services into Canada. Among wireless providers, the concentration is even more stark, with the incumbent’s being the largest companies which offer mobile service and include Bell Canada, Rogers Communications, and Telus. Each of these companies operate subsidiary brands that use their infrastructure.

The Canadian telecommunications service provider industry has a history of granting government agencies access to subscriber information for criminal investigations or other security reasons without first requiring a warrant or judicial order compelling the provision of such information. This practice has stopped following a Supreme Court of Canada decision in 2016. Furthermore, due in part to pressure from Canadian privacy advocates and academics in the form of open letters, parliamentary questions, and a data access request campaign, some Canadian telecommunications service providers now release transparency reports which provide some statistical reporting concerning the regularity at which government agencies request, and receive, information pertaining to companies’ subscribers and customers.

Access My Info: Canada

Data Collection

In 2016, the AMI Canada team recruited five participants who individually sent data access requests (DARs) to five different telecoms: Bell, Fido, Rogers, Shaw, and Wind. Such requests can be issued to companies per PIPEDA and legally compel companies to respond to such requests. We analyzed only one request per company.

Results

All Canadian telecommunications companies who were issued DARs responded to requests for access to personal data within the mandated 30 day period.

Table 2 lists the companies that DARs were sent to, the date that the DAR was issued, and the date of the first response from the company.

| Company | Request Date | First Response Date |

|---|---|---|

| Bell | 2016-09-30 | 2016-11-29 |

| Fido | 2016-08-26 | 2016-09-09 |

| Rogers | 2016-08-26 | 2016-09-08 |

| Shaw | 2016-06-23 | 2016-08-18 |

| Wind | 2016-06-22 | 2016-07-18 |

2016 DAR Issuance and Response Dates

Most companies responded to the question of whether data had been shared with law enforcement; in the case of the participant’s DARs, all of the companies indicated that data had not been shared with law enforcement or other third parties. This direct responses received from companies stands in contrast to the results of DARs asking the same question in 2014. During the 2014 research project, no company provided a clear or direct response to this same question.

All companies responded with some form of cover letter that acknowledged the receipt of the request and, typically, also provided some general responses to the questions in the DAR. DARs issued by participants also asked for access to technical data that was associated with the requester, such as IP address logs or geolocation information. Companies were unwilling to provide this data free of charge, and there was significant variation in how much money was required before technical data would be disclosed. In most cases the proposed fees were in the hundreds of dollars.

These costs served as a significant barrier to access, as our research participants did not pay for these data and therefore could not obtain full access to their data. The cost for access and introduction of more steps required to get access are hypothesized as establishing barriers for persons to access their own personal information.

| Company | Fee requested? For what? | Tell requester if data shared with law enforcement? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bell Canada | Will provide a cost estimate for historical assigned IP addresses upon request | Says they have to check with authorities first and to inform Bell whether the request wants the company to do so | Generally responded to most questions asked but failed to provide data retention period information. |

| Rogers Communications / Fido Solutions | Detailed SMS and call metadata including cell tower info ($100/month); Call logs beyond 18 months old ($15/month) | Yes | Generally responded to most questions. Stated the companies retain call log/SMS metadata (cell tower assignments) for 13 months. Asserted that the companies do not collect geolocation data. Provided IP address retention periods (7 days mobile; 13 month home Internet). |

| Shaw Communications | Historical assigned IP addresses ($250 per year per modem) | Yes | Generally responded to most questions. Did not provide data retention periods. Asserted the company does not collect location data as they do not provide mobile services at the time research was conducted. |

| Wind Mobile (now Freedom Mobile) | Stated metadata could be retained but did not mention that customer could get access to retained information.Participant did not follow up with additional requests for clarity to the company. | Yes | Generally responded to most questions. Indicated customers can get access to retained call logs for 90 days but did not specify the company’s own retention period. Provided detailed scenarios in which geolocation data may be collected such as in an e911 event, and the company provided a statement saying such data was not collected for the requester. |

Summary Analysis of DAR Responses from Telecommunications Service Provider Data in Canada, 2016

Recommendations

DARs can be a valuable method for understanding the kinds of information which are collected, retained, processed, and handled by private companies. However, our study found that Canadian Telecommunications Service Providers’ processes surrounding DAR-handling and -processing were immature. Advancing DAR practices and policies requires either private-sector coordination to advance individuals’ access to their personal information or regulatory coordination to clarify how private organizations ought to provide access to the information of which they are stewards.

Below are three recommendations from our full report of steps companies can take before, during, and after requests to improve the process by which citizens can obtain access.

Before request:

- Companies should review their access processes and assess where improvements could be made to reduce cost, reduce, or make more user-friendly their identity verification steps, and streamline security procedures.

During request:

- Companies should publish data inventories describing all the kinds of personal information that they collect and freely provide copies of a small set of representative examples of records for each kind of personal information to subscribers upon request.

After request:

- Companies should collaborate within their respective industries to establish common definitions for personal data to which common policies are applied, such as subscriber data, metadata, and content of communications, amongst others.

Learn More

Andrew Hilts, Christopher Parsons, and Masashi Crete-Nishihata, 2018, “Approaching Access: A look at consumer personal data requests in Canada,” Citizen Lab, University of Toronto.

Australia

Adam Molnar (University of Waterloo)

Key Findings

- Barriers to Access: Many telecommunication companies failed to comply to requests for reasons unknown.

- Variation in Responses: For those that did reply, information was uneven in terms of scope of information disclosed, guidance, and pricing.

Background

In Australia, the relevant statutory authority for privacy and data access rights is the Privacy Act 1988 (Privacy Act). In 2014, the Privacy Act was reflected in a policy guidance document known as the ‘Australian Privacy Principles’ (APPs) as a way to simplify the explanation of the mandatory cornerstones of the Australian Privacy Act.

Two items are particularly relevant regarding subscriber access to telecommunications information under the APPs. The first, s.6(1) of the Privacy Act, is the legal definition of ‘personal information.’ Personal information is defined in the Act as “any information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable.” Common examples of personal information under the Act include an individual’s name, signature, address, phone number, date of birth, bank account details, and so on. The term “about” is particularly salient in the context of data access requests because it refers to personal information that may actually be broader than the aforementioned examples of data that would still identify an individual. For example, information “about” an individual might include a vocational reference or an assessment about an individual’s career, or personal views that can be expressed by an author. Together, these two elements delimit the scope of information that is defined as constituting personal information. In a notable case in the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (Grubb v Telstra), IP addresses were excluded from the definition of personal information because they were legally defined to be about Telstra business practice rather than about Mr. Grubb. This position was upheld in Federal Court in an appeal by the Australian Privacy Commissioner. While IP addresses are currently not included in the legal definition of information in Australia, some legal commentators insist that the issue remains unresolved given the narrow terms of appeal that the Privacy Commissioner pursued in the Federal Court.

The second relevant item under the APPs refers to access and correction of personal information (APP 12 and 13). Entities that fall under the Privacy Act (“any entity that has an annual turnover of over $3,000,000”) are obligated to provide access to personal information that they hold upon request by an individual. The table below elaborates on the key items associated with access provisions under the Privacy Act and APP 12; combined, these items make explicit that persons living in Australia have the right to make Data Access Requests (DARs) to private organizations.

| Legal Justification | APP 12.1 – Access |

|---|---|

| Phrasing | “If an APP entity holds personal information about an individual, the entity must, on request by the individual, give the individual access to the information.” |

| Response deadline | The APP entity must: a. Respond to the request to access to the personal information “within a reasonable period” after the request is made; and b. Give access to the information in the manner requested by the individual, if it is reasonable and practicable to do so. Accompanying APP Guidelines state that, “as a general guide, a reasonable period should not exceed 30 calendar days.” |

| Fee for access | If the APP entity is an organisation, and the entity charges the individual for giving access to the personal information, the “charge must not be excessive and must not apply to the making of the request.” |

| Remedies if unsatisfied with response? | 12.9 Refusal to give access“If the APP entity refuses to give access to the personal information because of sub clause 12.2 or 12.3, or to give access in the manner requested by the individual, the entity must give the individual a written notice that sets out: a. the reasons for the refusal except to the extent that, having regard to the grounds for the refusal, it would be unreasonable to do so; and b. the mechanisms available to complain about the refusal; andc. any other matter prescribed by the regulations” 12.10 If the APP entity refuses to give access to the personal information because of paragraph 12.3(j), the reasons for the refusal may include an explanation for the commercially sensitive decision. Under s.28(1) of the Privacy Act, the Information Commissioner has powers to investigate possible interferences with privacy, either following a complaint or on the Commissioner’s own initiative. |

The Australian Telecommunications Service Provider (TSP) and Internet Service Providers (ISP) market is best understood as a ‘mixed’ market of network providers (wholesalers) and service providers (resellers). There are public agencies that both own infrastructure and provide service (i.e., National Broadband Network), there are private entities that both own infrastructure and provide services (i.e., Telstra, Vodafone, and Optus) and, lastly, there are private entities that exist solely as service providers which have ‘leased’ access to the infrastructure (i.e., Jeenee and Amaysim). The Australian market raises considerations with regard to eligibility under the APPs and comparisons within and across network owners versus service providers. For instance, smaller companies such as Amaysim run on Optus’ network, yet exist solely as a service provider. As a result, their particular link into telecommunications infrastructure means that they have access to different types of data, which influences the scope and type of data that can be disclosed under both subscriber and law enforcement requests.

Access My Info: Australia

Nine volunteers submitted written data requests by mail between the periods of December 2015 and February 2016. One volunteer made a request to Telstra, three volunteers requested to Optus, one volunteer to iiNet, one volunteer made two different requests to Vodafone. One volunteer also made a request to TPG, two volunteers made a request each to Amaysim, and one volunteer made a request to Jeenee. The table below provides a detailed itemisation of the timeline associated with requests issued to each company and the companies’ response dates.

Data Collection

| Company | Request Date | First Response Date |

|---|---|---|

| Telstra | Dec 12 2015 (online portal) | 1st Jan 25 2016 with invoice for retrieval (paid)2nd data provided on March 2 2016 |

| Optus | Dec 12 2015 (First Request) | NoneFeb 25 2016 Phone Call made – no trace of request |

| Optus | March 15 2016 (Second Request) | None |

| Optus | Feb 2 2016 (Third Request) | Mar 3 2016 – contacted subscriber by phone, told customer they would need subpoena to access the data, subscriber requested information via email, which they sent that day.Mar 16 2016 – Subscriber replied to email asking why info couldn’t be released under APPs and received no reply. |

| iiNet | Dec 12 2015 | No reply |

| Vodafone | Dec 12 2015 (First Request) Feb 9 2016 (Second Request) | No replyReply from Vodafone on Mar 3 2016 noting receipt of both requests, and included attached letter detailing costs for retrieval, including a Nondisclosure Agreement (bit more on what the NDA was for) |

| TPG | Dec 12 2015 | Mar 7 2016 reply seeking clarification on request. Volunteer didn’t follow up. |

| Amaysim | Dec 12 2015 (First Request) Dec 12 2015 (Second Request) | Feb 24 2016 replied with dataFeb 24 2016 replied with data |

| Jeenee | Mar 15 2016 | No response |

Results

The study indicates that a number of Australian telecommunications entities struggle to adhere to their lawful requirements under the Privacy Act and APPs. Numerous requests went unheeded and, for those that did respond, it seemed clear that internal procedures were lacking. Without such procedures, improper advice was offered by company staff which, in and of itself, established additional barriers to requesters accessing their personal information. Companies that repeatedly did not respond were not included in the table below (the exception being Optus who did not respond on two occasions, but did so on a third). For companies that did respond, there was variation in fees that were charged. Telstra and Vodafone (both infrastructure operators) charged significant fees that amounted to hundreds of dollars. Optus did not respond with any customer data, while Amaysim (an infrastructure ‘reseller’) did not charge any fees whatsoever when providing data. The table below elaborates on notable aspects of the results. Vodafone issued a letter stating that the sharing of any personal information disclosed to the requester would violate the standard form contract agreement that was agreed upon between the company and its customer.

| Company | Fee requested? For what? | Company Fee requested? For what? Tell requester if data shared with law enforcement? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telstra | Online portal was used to request information at varying prices. Total fee in study was 225 AUD for as comprehensive information as was available (see Appendix 1 below). | Yes | Information was disclosed via encrypted zip file (password sent plain-text in separate email). |

| Optus | No fee requested, information requesting subpoena be attained to facilitate request | Yes | Generally responded to most questions when in conversation. No information provided apart from improper advice citing subpoena requirement and then no response when asked to clarify whether this information was correct. |

| Vodafone | Fees provided in hourly rates (60-80 per hour) but no information provided on how many hours would be involved for retrieval | Yes | Generally responded to most questions. Retention periods disclosed in letter far exceed the mandatory data retention requirements under the Telecommunications Interception and Access Act (1979) of 2 years. Letter further cited that standard form contract stipulated that no information from the letter could be disclosed, and to do so would be a breach of the standard form contractual agreement. |

| Amaysim | No fee requested. | Yes | Provided quick and fulsome reply of data that is visible to their network as a reseller. |

Australian Data

Recommendations

While the Australian Privacy Act and APPs provide a clear framework for consumers to understand what information is collected, retained, and processed by TSPs and ISPs, it can be challenging for individuals to exercise their rights. DARs were unevenly responded to by TSPs and ISPS, leading to uneven outcomes that posed significant barriers to access. Furthermore, the costs companies demanded before processing some requests were either prohibitive for everyday consumers or were not clearly communicated.

Four main recommendations can be drawn from the Australian case:

- Companies should review their data access processes, and assess where improvements could be made to reduce cost, reduce or make more user-friendly their identity verification steps, and streamline security procedures. These reviews should culminate in clear training to front-line customer staff to familiarise them with how to facilitate DARs.

- Companies should publish data inventories describing all the kinds of personal information that they collect and freely provide copies of a small set of representative examples of records for each kind of personal information to subscribers upon request.

- Further clarity be given regarding the legality of non-disclosure agreements in standard form private contracts as they relate to statutory legal frameworks.

- Companies should collaborate within their respective industries to establish common definitions for personal data to which common policies are applied, such as subscriber data, metadata, content of communications, etc. Such policies should be developed and implemented by operators as well as resellers of TSP and ISP services in the Australian market.

Hong Kong

Lokman Tsui (Chinese University of Hong Kong)

Key Findings

- Telecommunication companies and Internet providers in Hong Kong argue that IP addresses and geolocation records are not personal data and therefore they are not required to give users access to this data.

- The only data users got back were call records and account information.

- The companies also did not tell users whether their data had been shared with third parties such as law enforcement agencies.

Background

Adopted in 1996 by the Hong Kong government, the Personal Data Privacy Ordinance (PDPO) is the first major personal data protection framework in the Asia-Pacific region. A key provision of the PDPO is the “data access” principle, which allows residents to ask data controllers for information held about them, and to correct it if it is inaccurate.

| Legal justification | Data Protection Principle 6 of the Personal Data Privacy Ordinance is the Data Access and Correction Principle |

|---|---|

| Phrasing | “A data subject must be given access to his/her personal data and allowed to make corrections if it is inaccurate.” |

| Response deadline | Within 40 calendar days after receiving the request |

| Fee for access | A telecommunications company may impose a fee for complying with a DAR which should not be excessive. It should clearlyinform the requestor what fee, if any, will be charged as soon as possible and in any event not later than 40 days after receiving the DAR. |

| Remedies if unsatisfied with response? | An individual may file with the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data a written complaint against an organization |

The seven major telecommunication companies and Internet providers in Hong Kong are SmarTone, Three, Hong Kong Telecom, Hong Kong Broadband, i-Cable, China Unicom, and China Mobile. Most have local ownership (Hong Kong Telecom, Hong Kong Broadband, i-Cable, SmarTone, Three) while two are owned by Mainland Chinese State Owned Enterprises (China Mobile, China Unicom).

Access My Info: Hong Kong

The data collection ran from January to August 2016.

We recruited ten volunteers who individually sent requests to the seven major telcos. We made sure each telco was sent data access requests from at least two different individuals

| Company | Request Date | First Response Date |

|---|---|---|

| SmarTone | January 12, 2016 | February 5, 2016 (letter) |

| Three | January 24, 2016 | January 25, 2016 (phone) |

| Hong Kong Telecom | January 18, 2016 | January 22, 2016 (phone) |

| Hong Kong Broadband | January 18, 2016 | January 25, 2016 (phone) |

| i-Cable | January 21, 2016 | not recorded |

| China Unicom | February 17, 2016 | March 1, 2016 (letter) |

| China Mobile | January 14, 2016 | January 22, 2016 (phone) |

Results

All Hong Kong telecommunications companies responded to requests for access to personal data within the mandated 40 day period. Only two responses were in writing, with the rest occurring over a phone call (despite the law mandating a response in writing). In their response, the companies often answered only a few of the questions and ignored the rest.

Several companies refused to answer the question of whether data had been shared with third parties, while some other companies over the phone answered that they would never share data with third parties, but would refuse to confirm this in writing. None answered the question whether they actually had shared data.

| Company | Fee requested? For what? | Tell requester if data shared with law enforcement? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SmarTone | – | No | Only sent call records. Responded with “N/A” to requests for other types of data including IP and geolocation. |

| Three | HK$200 for handling fee. HK$35 per month for bill statement/detailed call records. HK$80 for contract copy. | No | No response to requests for other types of data including IP addresses and geolocation. |

| Hong Kong Telecom | HK$250 for processing fee | No | Charged HK$250 for processing fee and explicitly states that it is not refundable notwithstanding if there is no data returned. Also requires users to submit another form before proceeding with DAR. |

| Hong Kong Broadband | HK$100 for copy of subscriber information | No | Over phone mentioned they cannot provide anything. |

| i-Cable | – | No | Over phone mentioned they cannot provide anything. |

| China Unicom | – | No | Letter mentions that user can get call records and account information online. Letter also argues that they are unable to provide other types of data, including IP addresses and geolocation. |

| China Mobile | HK$10 per month for bill statement. HK$30 for call records. HK$100 for copy of contract. | No | No response to requests for other types of data including IP addresses and geolocation. |

Recommendations

It would be helpful to have clear guidelines on what is and what is not considered personal data, including potentially sensitive data such as IP addresses associated with your account and geolocation records.

In addition, it would be helpful to have clarity on how companies decide what fee to request for their service. One company requested a fee even when it was unclear whether they could provide any data. Several users mentioned that the cost of the fee was prohibitive and that they would not continue their DAR because of it.

It would also be helpful for the telecommunication companies to provide a sample report, including an overview of the data types they collect, and for how long they keep this data.

Learn More

Lokman Tsui and Stuart Hargreaves, (2019) “Who Decides What Is Personal Data? Testing the Access Principle with Telecommunication Companies and Internet Providers in Hong Kong” International Journal of Communication

Stuart Hargreaves and Lokman Tsui (2017) “IP Addresses as Personal Data Under Hong Kong’s Privacy Law: An Introduction to the Access My Info HK Project” Journal of Law, Information & Science 25(2),

South Korea

Kelly Kim (Open Net Korea)

Key Findings

- A significant gap between the law and practice: South Korea has a strong data protection regime in text and theory that guarantees data subjects’ right to access all personal data, but our research found very superficial compliance to data access requests by the telecommunications companies we made requests to. All companies had online data request procedures, but the majority of companies only provided copies of their privacy policies in response to the data access requests. Korea Telecom provided some of the requested account information but did not give a fulsome response.

- Legal action: In response to this lack of compliance, Open Net Korea filed a lawsuit against Korea Telecom. On December 5, 2018, the trial court ruled in favor of Open Net Korea stating that the company must provide incoming call records to customers. Other data such as IP address logs were given during the course of the lawsuit. KT appealed.

- Third-party access to personal information: Since 2015, Korean telecommunications companies have started to tell users whether their data had been shared with investigation agencies. However, when we asked companies if they shared customer data with third parties such as private companies, only Korea Telecom provided responses.

Background

Korea has one of the strongest data protection regimes in the world. However, the effectiveness of the regime has been undermined by the extensive use of Resident Registration Numbers (RRNs) to verify real identities, and reluctance from government authorities and the Courts to investigate and punish companies for data breaches. Undoubtedly, there have been many data breach incidents in Korea largely due to the RRN system and the identity verification system as companies had to collect sensitive personal information including RRNs that increased the risk of a data breach.

Two data protection laws apply to telecommunications services in Korea: the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA) and the Act on Promotion of Information and Communications Network Utilization and Information Protection (Information and Communications Network Act, ICNA). The PIPA was introduced in 2011 and provides a general data protection framework for both the public and the private sectors. The ICNA was introduced in 1999, much earlier than the PIPA, and applies only to information and communications service providers, which are telecommunications business operators and for-profit online service providers. The ICNA prevails regarding telecommunication companies when the laws are in conflict (see Table 1).

| Legal justification | Article 30(2) of the ICNA (The PIPA applies supplementarily) |

|---|---|

| Phrasing | “Every user may demand a provider of information and communications services or similar to allow him/her to inspect, or to furnish him/her with, any of the following matters about him/her, and may also demand the provider to correct an error, if there is any error: 1. Personal information of the user, which the provider of information and communications services or similar possesses; 2. The current status of personal information of the user, which has been used by the provider of information and communications services or similar or furnished to a third party; and 3. The current status of personal information of the user, for which the user consented to the collection, use, or furnishing of personal information by the provider of information and communications services or similar.” |

| Response deadline | “Without delay”(c.f. “within 10 days” according to the PIPA) |

| Fee for access | There is no mention in the ICNA so the PIPA applies. According to Article 38(3), the data processor “may charge fees and postage (limited to cases where a request is made to send a certified copy by mail).” However, the fee should not exceed the actual cost of accommodating the request, and if the reason for making the request was caused by the data processor, then the data processor should not charge any fees. |

| Remedies if unsatisfied with response? | An individual may file with the Korea Communications Commission (KCC) a complaint against the service provider (data processor), and the KCC has the power to impose a fine of no more than 30 million won (approximately 26,500 USD) for any breach of the provision. |

Overview of Article 30(2) of the ICNA

The telecommunications sector in Korea is seemingly diverse and open to competition, with 96 ISPs operating as of May 2019. Nevertheless, the ISP market is dominated by three major companies: SK Telecom (SKT), Korea Telecom (KT), and LG U+. The mobile service market is also dominated by the same companies; each is a privately held and publicly traded company, although KT initially was a state-owned entity.

Investigation agencies have been abusing Article 83(3) of the Telecommunications Business Act (TBA), which allows warrantless access to subscriber information such as names, RRNs, and addresses. Although the ICNA clearly states that data subjects have the right to find out whether and with whom their data was shared, telecommunications companies had refused to tell users about the warrantless access. Open Net Korea and PSPD carried out the “Ask Your Telcos” campaign along with a series of lawsuits, and as a result, telecoms started to tell users whether their data had been shared with investigation agencies since 2015.

Access My Info: South Korea

The objective of Access My Info (AMI) South Korea is to investigate the kinds of information that are collected and retained by three major telecommunications companies—SKT, KT, and LGU+—as well as the effectiveness of the legally guaranteed inspection right or right to information.

Data Collection

The AMI South Korea pilot study was conducted in two phases. The first phase was to find out whether the telecommunications companies have procedures for the inspection requests under the ICNA (Data Access Requests, DARs). The second phase was to find out whether the Access My Info project launched in Canada would be feasible in South Korea.

Phase 1 (January – February 2016)

On January 18, 2016, Open Net Korea published an announcement on its website to recruit volunteers. Initially, 10 volunteers were recruited per company. Those volunteers were asked to make phone calls or visit stores or customer service centers to figure out ways to make DARs for the three types of information prescribed by Article 30(2) of the ICNA between 26-29 January 2016.

Phase 1 research showed that all three telecoms (SKT, KT, LGU+) had online request systems in place. Users could make a DAR by logging-in to companies’ websites and verifying their identity with the identity verification services provided by verification agencies. Volunteers were asked to make the online request, but not all of them completed the process. In the end, 3 responses for SKT, 3 responses for KT, and 2 responses for LGU+ were received. The online responses of each company were identical so no further volunteers were recruited.

For SKT and LGU+, the online response to a DAR was generated instantly because it was just a copy of their privacy policies, whereas KT took one day to respond and provided more information than the other companies.

Phase 2 (August -September 2016)

The objective of Phase 2 was to test whether the AMI approach—drafting and sending DAR letters to telecoms—would produce different results than using the online request systems tested in phase 1. Open Net Korea drafted a DAR letter for each of three companies (SKT, KT, and LGU+) and published a new recruit announcement on 11 August 2016. This time, the requests were to be made in two steps: first by making a DAR using the online process and then by sending a formal AMI letter to each company’s privacy officer via email. Volunteers were requested to provide Open Net with all of the companies’ responses. In the end, 5 volunteers returned their responses (4 responses for SKT and 1 response for LGU+). Companies provided apparently automated email responses that instructed users to use the online request system or visit the offline customer service centers for more information. Phase 2 stopped here because it was clear that the result would be the same as Phase 1.

Results

All three telecommunications companies had online request procedures. When users made DARs by email or phone, they directed users to make online requests. Although telecoms responded to DARs “without delay” (within 2 days), SKT and LGU+ did not disclose any meaningful information in their responses. The responses provided were just copies of company privacy policies, listing items of personal information collected and the purposes of collection and use that are common to all users. It is hard to understand the reason for requiring users to log in to make a DAR to get an identical copy of the publicly disclosed privacy policy. KT had the best practice among three because it provided a personalized set of information, disclosing what personal information it retains in a table format, and what personal information was shared with which third party on what date of the user who made the DAR. This difference may be the reason why SKT and LGU+ returned the responses instantly on the webpage whereas it took KT at least a day to respond. KT sent an encrypted PDF document containing the information to the user’s email. However, the response did not include all the user data that KT claims it collects in its privacy policy, such as call/SMS logs, geolocation data (cell tower location, GPS data), IP address logs, and other service usage information including cookies.

| Company | Fee requested? For what? | Data Provided | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| KT | No | 1) Table showing whether or not KT retains 12 types of personal information (name, RRN, address, phone number, email, ID, Bank account no., etc.) 2) details of data sharing with third parties (except investigation agencies and the court) 3) details of the user’s consents given to data collection | KT had the best practice among three telecoms especially regarding 2) and 3). However, it provided a very limited data set when a data subject has a legal right to access all personal data. |

| SKT | No | Copy of the relevant parts of its Privacy Policy | No substantial data provided |

| LGU+ | No | Copy of the relevant parts of its Privacy Policy | No substantial data provided |

Summary Analysis of DAR responses from three telecoms in South Korea, 2016

Korea Telecom Lawsuit

Open Net Korea’s General Counsel Kelly Kim issued a DAR to her telecom KT with other volunteers at Phase 2. When KT replied to her DAR letter instructing her to make an online request, she replied back saying that she already did and that KT should provide full access to all of her personal data that KT claims to collect in its privacy policy. In the next email, KT instructed her to visit an offline customer service center and make DARs for her phone call records, payment records, and the subscription contract. She followed the instruction and received outgoing call/SMS records, payment records, and the subscription contract. However, she still could not get full access to her personal data.

In reaction to this lack of compliance, she resorted to legal actions. On February 24, 2017, Ms. Kim filed a lawsuit against KT requesting access to her personal data except those already provided. On December 5, 2018, the trial court ruled in favor of Open Net stating that the company must provide incoming call/SMS records to customers. Other data such as IP address logs were given during the course of the lawsuit, although KT initially refused to provide any data beyond what had been provided. The court reasoned that customers have contractual rights to request access to the data that KT claimed to collect in its privacy policy. It was a mixed victory because the court dismissed Open Net’s primary claim that incoming call records are personal information under the ICNA and that customers have a legal right to access.

KT appealed the decision and the case is currently pending at the appeals court. Open Net aims to get a decision clearly stating that all data of a customer collected by a telecommunications company are personal information under the ICNA and that customers should be given full access to the personal information.

Recommendations

For all three telecommunications companies:

- Telecoms should provide full access to a customer’s personal information they collect when issued with a DAR.

For KT:

- KT has the best practice among three telecommunications companies, especially regarding the disclosure about information sharing with private third parties. However, KT could improve its DAR procedure by allowing a customer to make one request for all personal information.

For SKT and LGU+:

- Not providing any information in response to a DAR is clearly in violation of the ICNA. SKT and LGU+ should develop a DAR procedure that produces a meaningful disclosure, i.e. full access to all personal information of a customer.

For the data protection authorities, especially the KCC:

- Authorities should make clear and detailed DAR guidelines for customers and companies. In September 2018, the KCC published the revised “Online Personal Information Processing Guidelines” that provides detailed instructions and examples on how companies, especially telecommunication service providers, should process and respond to DARs. It is a result of Open Net’s AMI campaign and advocacy. However, the telecoms haven’t improved their practice according to the guidelines until now. The KCC should strongly enforce the guidelines so that it is duly complied.

Learn More

OpenNet Korea, “Ask Your Telcos Campaign Report”

Indonesia

Sinta Dewi Rosadi (University of Padjadjaran)

Key Findings

- Lack of data protection law: Indonesia only has the Ministry of Communications and Informatics Regulation on Personal Data Protection in Electronic System. This regulation is insufficient, as it does not impose strong obligations on telecommunications companies to protect user data and only establishes administrative (as opposed to Criminal) penalties. As a result, the public does not use their right to access. The Ministry of Communication and Informatics (MOCI) has drafted a New Data Protection Law and in 2019 submitted the draft bill to the Parliament as a prioritized law for Parliament’s deliberation.

- Similar responses from telecommunication companies: None of the telecommunication companies provided user data in response to the Data Access Requests. However, the companies did respond to the majority of questions asked about their data practices and stated that they never disclose any consumer personal data information to third parties.

Background

The protection of personal data in Indonesia was not the main political agenda until 2008. Prior to this time the government placed greater focus on developing telecommunication infrastructure and emphasized the need to address “negative content” on the Internet, such as pornographic material, online hate speech, and “fake news.”

In 2008, Indonesia established the Electronic Information and Transactions Law which stipulated personal data protection. This general regulation was supplemented in 2010 in line with increasing number of Internet and social media users, and growing e-commerce adoption. Specifically, the government of Indonesia vis-a-vis the Ministry of Communications and Informatics passed several implementing regulations to protect personal data amidst the growing trend of big data collection and analysis. The need for a personal data protection law in Indonesia is increasing because the desire by public and private organizations to intensively collect data, about wide swathes of people to advance their objectives.

In 2016, the Ministry of Communications and Informatics issued Regulation No 20 of 2016 on Personal Data Protection in Electronic System as an implementing regulation of the Electronic Information and Transactions Law. The new Regulation was motivated largely by non-consensual and bulk collection of personal data by businesses and government entities following the launch of the national Electronic Identity Card.

The regulation stipulates several principles pertaining to the processing of personal data:

- Personal data as a privacy right;

- Confidentiality of personal data, save for the consent given or as allowed by law;

- Consent as basis;

- Relevance with the purpose of procurement, collection, processing, analysis, storage, display, publication, transmission, and dissemination;

- Reliability of electronic system in which data is processed;

- Good-faith written notification of breach of personal data protection to the data owner;

- Provision of internal rules on the governance of personal data protection;

- Responsibility on personal data which is in control of the user;

- Access and correction to personal data by data owner; and

- Integrity, accuracy, lawfulness and newness of personal data.

Four telecommunication companies (Telkom, Telkomsel, Indosat Ooredoo, XL-Axiata) control an 85% market share in Indonesia’s mobile phone market. Although the country has a population of 260 million about 300 million mobile phones are in use in Indonesia, implying that some people use two or more mobile phones. PT Telkom, of which Telkomsel is a subsidiary, is the incumbent with over 174 million subscribers. Indosat Ooredoo is the second largest company with 63 million cellular subscribers that offers prepaid and postpaid services also as incumbent for providing international services. XL-Axiata is a new player and become the first mobile services operator that offers mobile communications.

Access My Info: Indonesia

Four volunteers were recruited to send requests to the major telecommunications companies in Indonesia: Telkom, Telkomsel, Indosat Ooredoo, XL-Axiata. All telecommunications companies in Indonesia responded to requests for access to personal data within 14 days (See Table 1).

| Company | Request Date | First Response Date |

|---|---|---|

| Telkomsel | 2016-03-4 | 2016-03-11 |

| Indosat | 2016-03-4 | 2016-03-14 |

| Telkom | 2016-04-10 | 2016-04-20 |

| XL-Axiata | 2016-04-20 | 2016-04-27 |

Response times for data access requests to each telecommunication company.

Results

None of the companies provided customer data in response to the DAR. However, the companies did generally answer the questions made in the DAR. Table 2 provides an overview of company responses.

| Company | Are data operators required by law to respond to requests for access to personal data? | Company responses for the questions | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telkomsel | According to Ministerial Regulation No.20/2016, data subject have an access right to their personal data (historical access) |

|

|

| Indosat Ooredoo | The company stated that they never disclose any personal information to third parties on the legal basis that the Telecom Act forbids any disclosure of personal information to third parties unless it is to comply with legal enforcement requirements | The Company responded to all questions | Per the company’s privacy policy, Indosat Ooredoo may share Personally Identifiable Information or non-personally-identifiable information with third party service providers to the extent that it is reasonably necessary to perform, improve or maintain the Indosat Ooredoo Service.Indosat Ooredoo may share non-personally-identifiable information (such as anonymous User usage data, referring / exit pages and URLs, platform types, asset views, number of clicks, etc.) with interested third-parties to assist Indosat Ooredoo in understanding more about user behavior on Indosat Ooredoo Service. https://indosatooredoo.com/id/personal/privacy-policy |

| PT. Telkom INDONESIA | The company never disclose or share personal data information with third parties. These obligations were based on Telecom Law | The Company responded to all questions | Generally responded to most questions. The Company does not have a privacy policy on their webpage. |

| XL | The company stated that they respect the privacy of consumer personal data and never disclose or share personal data information with third parties | The Company responded to all questions | The company does not have a privacy policy in their webpage. In the terms and conditions they only state the consumer obligation and do not outline any obligations placed on how the company must treat personal data. |

Summary of responses to data access requests from each telecommunication company.

Recommendations

The government of Indonesia is committed to supporting the development of information technology through law and regulation for the growth of e-commerce, the development and utilisation of information technology, and to provide for laws to protect the right to privacy. However, personal data protection in Indonesia is largely a patchwork approach; the 2016 regulation is only a Ministerial Regulation which does not impose strong obligations on telecommunications operators and only establish administrative (as opposed to Criminal) penalties.

Data access requests will not assume the force of legal obligations on telecommunication companies unless Indonesia establishes a specific Personal Data Protection Law. In responding to the requests, the Indonesian Telecom Operators always stated the Telecom Law, and not the Ministry of Communications and Informatics’ Ministerial Regulations on Data Protection, which reveals what rules and requirements the companies have established as most important to comply with.

Malaysia

Sonny Zulhuda (International Islamic University of Malaysia)

Key Findings

- Lack of Legal Readiness: Telecommunication companies in Malaysia were not yet ready to fully respond to data access requests, which shows that the rules of the Personal Data Protection Act have not yet been fully implemented.

- Inconsistent Practices: Telecommunication companies did not follow a standard method for responding to data access requests. Their practices followed respective company policies rather than legal or regulatory requirements.

- Incomplete Data: Providers were generally willing to disclose basic personal data and service bills to data subjects, i.e., customers, but did not share other types of personal information including call records, texts received or sent, nor details about their practice of collection and processing of personal data.

Background

In June 2010, Malaysia introduced the Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (Act 709) (“PDPA” or “the Act”), with the objective of regulating the processing of personal data in commercial transactions. The Act applies to any person in either of two conditions. First, a person who processes personal data in respect of commercial transaction. Secondly, it applies to any person who has control over, or authorises the processing of any personal data (PDPA section 2(1) ) . The person who processes such data is called a “data user” while the individual whose data is processed is a “data subject.” The Act however does not apply to the Federal Government and State Governments (PDPA, section 3(1) ); this failure to comprehensively apply the Act constitutes a major impediment to protecting individuals’ personal information. Furthermore, the Act is inapplicable to personal data processed outside Malaysia unless that personal data is intended to be further processed in Malaysia (PDPA, section 3(2) ).

Under the Access Principle in section 12 of the PDPA, a data subject shall be given access to their personal data held by a data user and be able to correct that personal data where the personal data is inaccurate, incomplete, misleading, or not up-to-date. This right to access and to make corrections may however be waived if compliance with a request to such access or correction is refused under circumstances provided by the Act. The law compels a data user to respond in the prescribed period by either complying with the request (i.e., by providing the data subject with data requested) or by notifying the refusal in writing (upon prescribed reasons only). This principle has set up a new standard of transparency and accountability for those who are involved in the processing of personal data. Furthermore, according to the subsidiary rule under the Act, upon receiving the data access request, the data user must acknowledge the receipt of such request (Personal Data Protection (PDP) Regulations 2013, regulation 9.) However, the law is silent on how the communications should take place.

It is not entirely clear what kinds of information a data subject can request to access from the data user. Is a data subject entitled to ask questions about how a company handles their data? Though there is no specific provision on the right to ask questions about how a company handles personal data, the words of the law are broad enough to cover such questions. The PDPA, under its Notice and Choice Principle, provides that a data user shall provide a written notice to inform a data subject, among others, of the data subject’s right to request access to and to request correction of the personal data and how to contact the data user with any inquiries or complaints in “respect of the personal data” ( PDPA, section 7(1)(d) ). The last-mentioned phrases would arguably include right of a data subject to ask, for example, whether or not their personal data had been disclosed to any party.

It follows that informing a data subject about the third parties to whom personal data was, or is to be, disclosed is made compulsory from the beginning of the data process. According to the Notice and Choice Principle, a data user shall by written notice inform a data subject, among others, of the class of third parties to whom the data user discloses or may disclose the personal data (PDPA, section 7(1)(e) ). Note, however, that the requirement is only to notify the class of third parties which, absent a definition, means a group of parties belonging to certain classification and not the specific companies or organization which may be receiving the information. Nevertheless, the data subject may arguably be able to force a data user to name any individuals to whom the data has been disclosed by virtue of the other part of the statutory provision (PDPA, section 7(1)(d) ). However, if the personal data is to be disclosed to any party other than the class of third parties mentioned above, such disclosure must be made with the consent of the data subject (PDPA, section 8(b) ). By virtue of the PDP Regulation 2013, a data user must keep and maintain a list of disclosures to third parties that pertain to the personal data of the data subject that has been or is being processed by them (PDP Regulations 2013, regulation 5).

A data subject who makes a data access request (DAR) is arguably entitled to know about

how the data user handles data processing including any disclosure of data to a third party. In describing a data subject’s rights, the PDPA establishes that an individual is entitled to be informed by a data user whether personal data of which that individual is the data subject is being processed by or on behalf of the data user (PDPA, section 30(1) ). Since data “processing” is defined in section 4 of the PDPA to include “the disclosure of personal data by transmission, transfer, dissemination or otherwise making available,” it follows that an individual or data subject is entitled to be informed by a data user whether personal data is being disclosed or made available by the data user.

The PDPA establishes that, first, a data subject may have to pay a prescribed fee to the data user to initiate a data access request (DAR). Having paid the fee, the data subject may make a written data access request to the data user for information of the data subject’s personal data that is being processed by or on behalf of the data user. Furthermore, the data user is obliged to communicate a copy of the information to the data user in an intelligible form (PDPA, section 30(2) ). This communication of a copy of the data in an intelligible form is required by default, in so long there is no indication to the contrary (PDPA, section 30(3) ). While the Act is silent about the meaning of “intelligible form” it ought to be interpreted close to its natural meaning, which is in an easily and humanly readable format. The purpose of this clause is to ensure the data subject can generally understand the information without unnecessary difficulty and provide it in a language which is readily understandable by the general public. In Malaysia, that language would be either English or the national language of Bahasa Malaysia.

The data subject must authenticate themselves to the data user when preparing and issuing the DAR; such authentication must be completed before the data user can proceed with the request. While this requirement is implicitly established in the Act, insofar as the Act authorizes a data user to potentially refuse to comply with a data access request under section 30 if (a) the data user is not supplied with such information as he may reasonably require in order to satisfy himself as to the identity of the requestor (PDPA, section 32(1) ). For the purposes of identifying the requestor, such identification information means name, identification card number, address and such other related information as the Commissioner may determine (PDP Regulations 2013, regulation 5).

The actual means of communicating with a data subject is largely left undefined. According to Reg. 9(2) of the PDP Regulations 2013, upon receiving the data access request pursuant to subsection 30(2) of the Act, the data user shall acknowledge the receipt of such request. There is however no further guidelines as to how such acknowledgement should be made. Furthermore, when a data user complies with the DAR the information must be provided in such an “intelligible form” but the actual presentation of data may be either a copy of the data or “access without copy.” There is no other requirements in relation to the format of the response (PDPA, section 30(2) ). Per section 30(3) of the PDPA, the data user may provide the data as requested in some other form or formatting, including machine-readable format, when there is an indication to that effect from the data subject.

The Act also establishes that a fee may be prescribed by a data user. The fee was fixed to a maximum rate in the Personal Data Protection (Fees) Regulations 2013, as follows:

- For a request of personal data with a copy: MYR 10.00

- For a request without a copy: MYR 2.00

- For a request of sensitive personal data with a copy: MYR 30.00

- For a request of sensitive personal data without a copy: MYR 5.00

PDPA section 3 defines “sensitive personal data” as any personal data consisting of information as to the physical or mental health or condition of a data subject, their political opinions, their religious beliefs or other beliefs of a similar nature, the commission or alleged commission by them of any offence or any other personal data as the Minister may determine by order published in the Gazette.

Upon receiving a data access request, the data user has to respond within the prescribed time limit under the Act, which is a maximum period of 21 days from the date of receipt of the data access request (PDPA, section 31(1) ). The data user may extend such timeline provided that they must give reason(s) for such an extension. Thus the Act provides that a data user who cannot comply with a data access request within the 21-day period shall before the expiration of that period provide a written notice to inform the requestor that they are unable to comply with the data access request within such period and the reasons why they are unable to do so (PDPA, section 31(2) ). Upon fulfilling this requirement, the data user can extend their response time to a maximum of 14 days after the expiration of the original period stipulated before (PDPA, section 31(3) ). So, in total, their maximum response time is 35 days.

There are grounds on which a data user may refuse to comply with data access request. One reason is when the requestor fails to identify themselves. Second, a user may refuse a DAR if they are not supplied with information that is needed to locate the personal data requested in the DAR. Third, they may refuse the request when the burden or expense of providing access is disproportionate to the risks to the data subject’s privacy in relation to the personal data in the case in question. Fourth, a data user may also refuse a DAR if they cannot comply with the request without disclosing personal data relating to another individual who can be identified from that information unless they have consented or it would be reasonable to assume such consent. The same provision provides a few more situations where refusal may take place based on necessity or harm prevention. Similarly, data user may also refuse an access request if providing access would constitute a violation of an order of a court, disclose confidential commercial information; or it is otherwise regulated by another law (PDPA, section 32(1)(b)-(h) ). In any case where a data user refuses a DAR they must inform the requestor of their refusal by notice in writing within twenty-one days from the date of receipt of the data access request (PDPA, section 33).

The data subject can contest a refusal by way of forwarding a complaint to the PDP Commissioner. This right is in line with the general entitlement of the data subject to complain if they experience difficulties in obtaining access to their personal data, arguing that it violates their rights. The law allows the data subject to make a complaint to the PDP Commissioner in writing about an act, practice or request, where they must explain the details of such act, practice or request together with the nature of personal data of the data subject, and the potential contravention of the Act (PDPA, section 104).

Access My Info: Malaysia

As of the end of 2018, three main companies serviced 72% of mobile subscribers in Malaysia. Celcom provided service to 20%, Maxis 25% and DiGi 27%. In terms of the mobile telecommunications revenue, Maxis contributed to 34% of subscribers whereas Celcom and DiGi contribute to 27% and 24% respectively (Industry Performance Report 2018, MCMC).

Each company offers mobile line, wireless Internet, voice as well as data services. While Digi is a private entity, both Maxis and Celcom are public. Celcom’s substantial shares belong to the Malaysian government or government-linked entities. As of September 2019, none of them have produced a transparency report which discloses how they process personal data; the companies only provide a general statement about their privacy policy in their annual reports and public websites.

As part of the Access My Info in Malaysia project (”AMI” Project) conducted in 2016, we chose the three biggest telecommunications service providers in Malaysia, namely Celcom Axiata Bhd. (Celcom), Maxis Bhd. (Maxis), and Digi Telecommunications Sdn. Bhd. (DiGi)..

Data Collection

Following the guidelines given in their respective websites, the volunteers first made phone calls to the hotline numbers provided online. All these numbers are general line numbers; none were a special line for PDP-related complaints or requests. The volunteers asked service providers about the basic personal information of customers that are kept with the companies; records of phone conversations and text messages being sent and received; itemized bills; and the company’s policy on data integrity, data security and data disclosure. The request started with a phone call method. At Maxis and Digi, the volunteers were also informed that they should come to the service counters to obtain certain types of personal information. Celcom also advised the volunteer to come to the centre and speak to the staff there personally about their request.

Both Maxis and Digi were willing to disclose and share the basic personal information of the subscribers on the phone. However, when asked about the content of call recordings and text messages, they both could not comply. At Maxis and Digi, requests for call recordings and text details were responded differently by different staff. At first, the volunteers were told that such data cannot be obtained as they are not kept by the providers. During another phone-call, the response was that such data can only be obtained by visiting the customer centre. During visits to the customer centres, the volunteers were told that such information can only be obtained if there was a police report relating to the data requested. This shows that there is no uniform response given by the service providers on the same subject matter or request. For Celcom, interestingly, the volunteer who called was immediately informed to come personally to the service center. So, personal data was not obtained on the phone, but rather by asking for it at the service counter. However, the Celecom customer representative refused to disclose details about messages that had been sent out and received by the volunteer in a certain period of time.

Results

Despite the fact that the volunteers had specific queries about their personal data processing, none of the customer service representatives transferred the communications to a specific data protection officer in the given company, which meant that none of our volunteers spoke to the data protection officer or anyone in charge of personal data protection matters. At Maxis, when a volunteer requested to be connected to any data protection officer, the staff in charge was not willing to contact their data protection office. Instead, the staff member kept speaking to the volunteer to handle the queries on their own. In the case of Celcom, the volunteer who spoke with the company’s staff was immediately told to come personally to the service center on the basis that personal data could not be obtained on the phone and could only be obtained by asking on the counter. Furthermore, when requested, the staff member refused to disclose details about messages that had been sent out and received by the volunteer in a certain period of time. As for DiGi, the volunteer was told to use the existing web-based Online Customer Service (OCS) or otherwise to come to any Digi Centre in the town. As far as basic personal data is concerned, the person on the phone was willing to disclose information to the data subject.

The language of the replies varied between different providers and on different items. All the telecommunications providers were willing to help and to disclose basic personal information to the data subject, either through online platforms or on the counter after first making on-counter request personally. Meanwhile, on the request for itemized bill including record of numbers to whom phone calls were made, the providers required volunteers to come over the service center and make on-the-counter requests. DiGi stated that for the more sensitive data such as records of phone calls and text messages, the request would have to come from a law enforcement agency. None of our volunteers did requests about the collection or processing of subscribers’ location data and IP addresses data.

As the implementation of the PDP Act 2010 is still at its infancy, the outcome of this study is not necessarily surprising. As time passes, it is important to conduct another round of data access requests. Future research should highlight the rights of data subjects and and the obligations of the data users as prescribed under the specific data protection principles in the PDPA 2010. Also, a more precise scope of personal data needs to be requested during future access request studies.

There is another important development that may push the industry towards achieving better compliance with the PDPA. As of the end of 2017 the PDP Commissioner’s Office endorsed the new PDP Code of Practice for Telecommunications Industry. Telecommunications providers in Malaysia are required to comply with the Code. Though the Code does not change the rules of the game as generally prescribed by the PDPA, it will be interesting to see how certain specific rules be introduced to them so as to achieve better compliance with the Act. It is right to argue that now the telecommunications provider will have to be more aware, prepared and operational on the issues of personal data protection in their organizations.

Recommendations

Data Access Request (DAR) is a new right for Malaysian individuals relating to their personal data as processed by data users. Its introduction by the PDPA will eventually change the business process in Malaysia. Industries will need to provide such mechanisms in compliance with the principles of the law.

Telecommunications companies will be among those are greatly affected by DARs. With the rising prosecutions and cases relating to personal data abuses in recent years, data subjects will certainly be more aware about their right to DAR. This awareness will create stronger expectations of transparency from the data users. The provision and mechanism of DAR is the key to that transparency and accountability.

Based on our preliminary study, we found that the DAR handling and processing in Malaysia is still far from ideal. This finding is not surprising at all, considering that PDPA is only recently enforced and many in the industry are still catching up with the new law. Companies should however understand that this lack of compliance cannot be tolerated for a longer time. Soon data subjects will understand that DAR is an inherent right for them and cannot be abandoned.

Below are three steps companies can take to be better prepared with DARs.

- Data users shall review and improve their internal procedures in governing, managing and dealing with data processing, including more specifically about the scope and limitations of data access rights under the Law. All these need to be embedded in their privacy policies. During collection, for example, they need to have a proper procedure to inform data subjects about the data access request (DAR).

- Data users need to appoint a capable officer especially tasked with the DAR. The person or his office must be ready to serve inquiries, complaints and requests by data subjects relating to their personal data. They must be the focal point of communications and action in relation to data processing requests, complaints and the relevant action.

- Telecommunications companies should streamline their business process with the newly endorsed Code of Practice for telecommunications industry and to establish better communications between the players in the industry. This step is important in order to achieve a common standard in telecommunications industry that complies with the requirements of the Personal Data Protection Act 2010. In this respect, the Office of PDP Commissioners should be able to help with practical advice and recommendations.