Censored Contagion

How Information on the Coronavirus is Managed on Chinese Social Media

The analysis of YY and WeChat indicates broad censorship—blocking sensitive terms as well as general information and neutral references—potentially limiting the public’s ability to access information that may be essential to their health and safety.

Key Findings

- YY, a live-streaming platform in China, began to censor keywords related to the coronavirus outbreak on December 31, 2019, a day after doctors (including the late Dr. Li Wenliang) tried to warn the public about the then unknown virus.

- WeChat broadly censored coronavirus-related content (including critical and neutral information) and expanded the scope of censorship in February 2020. Censored content included criticism of government, rumours and speculative information on the epidemic, references to Dr. Li Wenliang, and neutral references to Chinese government efforts on handling the outbreak that had been reported on state media.

- Many of the censorship rules are broad and effectively block messages that include names for the virus or sources for information about it. Such rules may restrict vital communication related to disease information and prevention.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease, officially termed COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO), is an epidemic that surfaced in Wuhan city, in central China’s Hubei province, in early December 2019. As of March 2, 2020, COVID-19 had reached 65 countries and infected over 88,000 people. The WHO has declared the virus a global health emergency.

During the last week of December, 2019, doctors in Wuhan (such as the late Dr. Li Wenliang), began to notice a troubling unknown pathogen burning through the wards of their hospitals. They took to social media to issue warnings of this new disease thought to be linked to the Wuhan Seafood Market.

As the doctors tried to raise the alarm about the rapid spread of the disease, information on the epidemic was being censored on Chinese social media. On December 31, 2019, when the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission issued its first public notice on the disease, we found that keywords like “武汉不明肺炎” (Unknown Wuhan Pneumonia) and “武汉海鲜市场” (Wuhan Seafood Market) began to be censored on YY, a Chinese live-streaming platform.

Between January and February 2020, as the outbreak spread, a wide breadth of content related to COVID-19 was censored on WeChat (China’s most popular chat app), including criticism of the Chinese government, speculative and factual information related to the epidemic, and neutral references to Chinese government efforts to handle the outbreak that had been reported on state media.

This report presents results from a series of censorship tests on YY and WeChat that show that Chinese social media began censoring content related to the disease in the early stages of the epidemic and blocked a broad scope of content.

With over one billion monthly active users, WeChat is the most popular messaging app in China. According to a 2019 survey, over 50% of the correspondents said that they relied quite heavily on WeChat for information and communication. Moreover, the platform has become increasingly popular among doctors who use it to obtain professional knowledge from peers. Because of social media’s integral role in Chinese society and its uptake by the Chinese medical community, systematic blocking of general communication on social media related to disease information and prevention risks substantially harming the ability of the public to share information that may be essential to their health and safety.

Controlling COVID-19 Information

As the government of China attempted to respond to the outbreak, it also worked to control what information on the disease was available online and in the media.

Government briefings and media reports show that the Chinese authorities delayed releasing information on the epidemic to the public. When eight individuals (at least two of which were medical experts) tried to warn the public of the then mysterious outbreak on December 30, 2019, they were silenced and punished by local authorities in Wuhan for “spreading rumours” and “disturbing social order.”

On Feb 5, 2020, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the top-level Internet governance agency in China, issued a public statement stressing that it would punish “websites, platforms, and accounts” for publishing “harmful” content and “spreading fear” related to COVID-19. The CAC singled out Sina Weibo, Tencent, and ByteDance in the statement, saying that it would carry out “thematic inspection” of their platforms.

Chinese authorities continue to warn the public of the consequences of “spreading rumours.” A non-comprehensive collection of police announcements on the punishment of “rumour-mongers” shows that at least 40 people were subject to warnings, fines, and/or administrative or criminal detention around January 24 and 25, 2020. Another announcement points to a much larger number, detailing 254 cases of citizens penalized for “spreading rumours” in China between January 22 and 28, 2020.

Methods

This section outlines the methods that we used to document COVID-19 censorship on YY and WeChat.

Documenting Censorship on YY

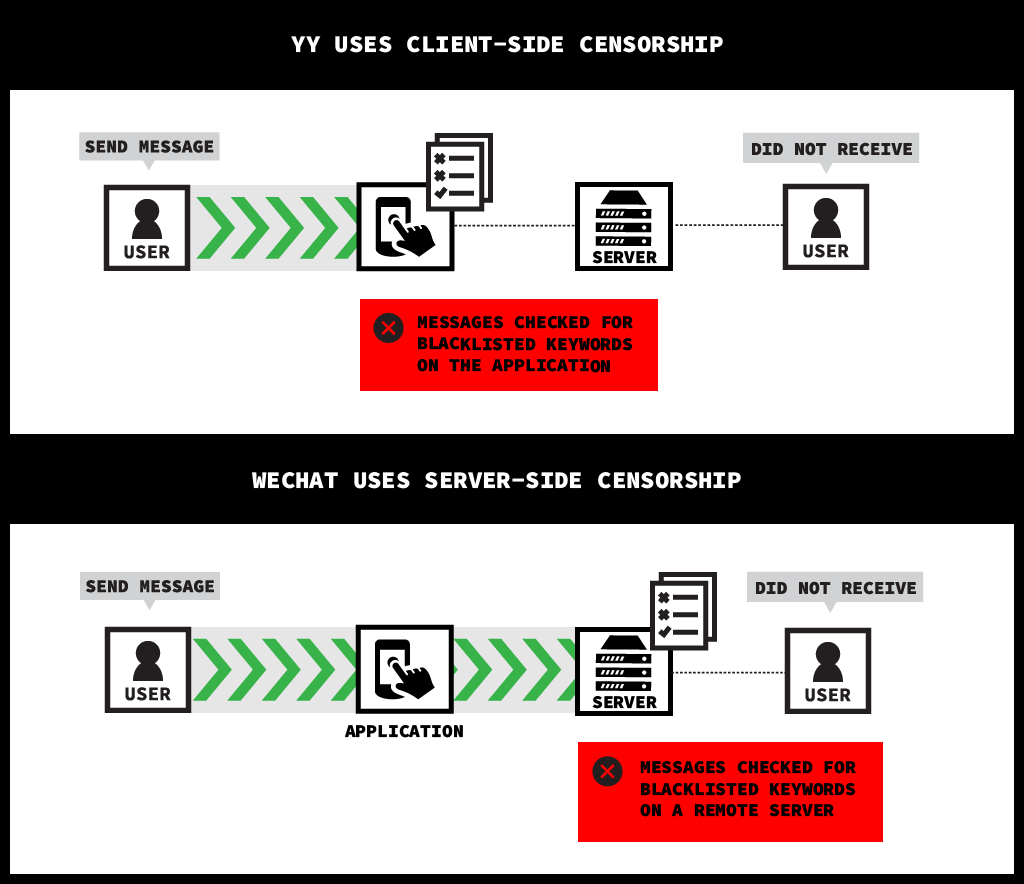

YY censors keywords client-side meaning that all of the rules to perform censorship are found inside of the application. YY has a built-in list of keywords that it uses to perform checks to determine if any of these keywords are present in a chat message before a message is sent. If a message contains a keyword from the list, then the message is not sent. The application downloads an updated keyword list each time it is run, which means the lists can change over time.

This type of censorship implementation makes it possible for us to reverse engineer the application and then download and decode the exhaustive list of keyword lists YY uses to trigger censorship. Using this method, we have been tracking all updates to YY’s keyword blacklist since February 2015 on an hourly basis.

Documenting Censorship on WeChat

WeChat censors content server-side meaning that all the rules to perform censorship are on a remote server. When a message is sent from one WeChat user to another, it passes through a server managed by Tencent (WeChat’s parent company) that detects if the message includes blacklisted keywords before a message is sent to the recipient. Documenting censorship on a system with a server-side implementation requires devising a sample of keywords to test, running those keywords through the app, and recording the results. In previous work, we developed an automated system for testing content on WeChat to determine if it is censored.

WeChat censors a message based on whether it contains a blacklisted keyword combination. A keyword combination consists of one or more keyword components. When a keyword combination consists of only one component (e.g., “习近平到武汉,” “Xi Jinping goes to Wuhan”), then a message is filtered if it contains that component. For a keyword combination that contains more than one component (e.g., “习近平” and “疫情蔓延,” “Xi Jinping” and “Epidemic Spread”), a message is censored only if every component in the combination appears somewhere in the message, although not necessarily adjacent to each other. In this case, censorship rules may be implemented more precisely.

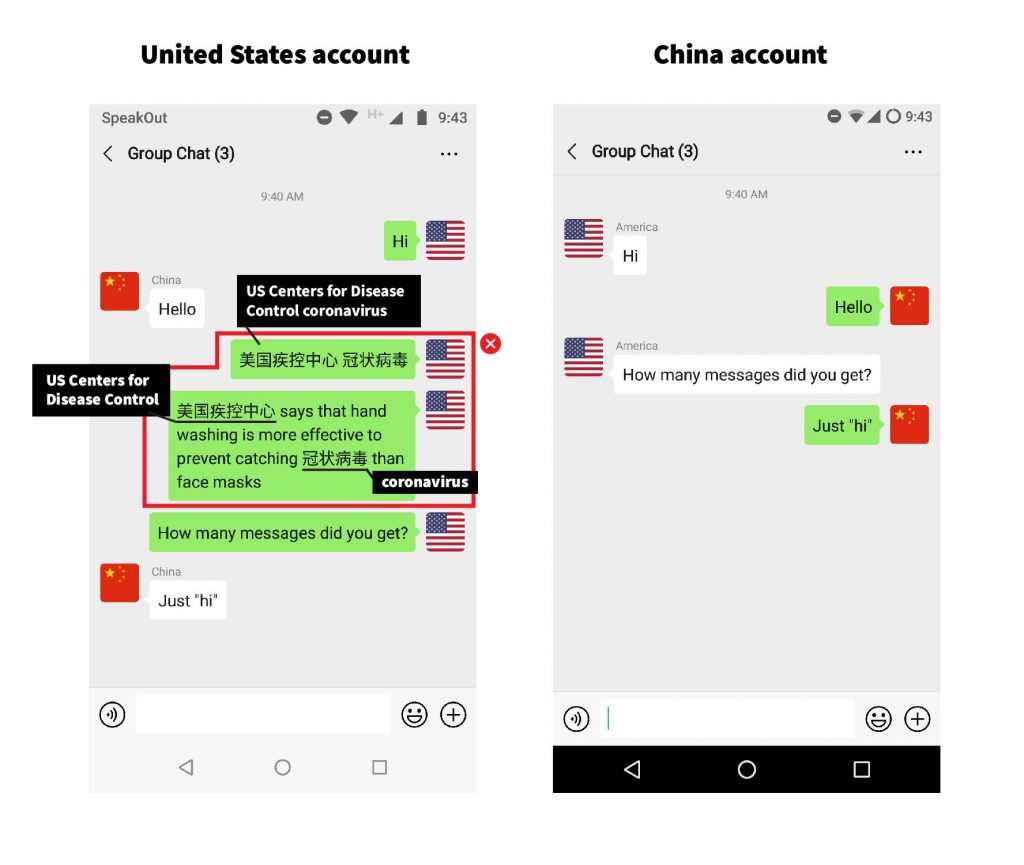

Scripting Chats

To discover censored keyword combinations on WeChat, we script group chat conversations. We programmatically collect articles listed on the front page of the sample websites. We then extract article text, consisting of each article’s title and body text, from each article and send it in a WeChat group chat using three test accounts: one registered to a mainland Chinese phone number and two registered to Canadian phone numbers (none of these accounts were tied to actual users). We use one of the Canadian accounts to send messages and the second Canadian account to perform no actions, acting only as a passive user to facilitate the creation of a group chat (i.e., a chat with three or more users). Throughout this process, we limit our test accounts to interacting with each other in the group chat and never interact with real users of the platform. We use the Chinese account to passively monitor whether messages sent in the group chat have been filtered.

After we send the extracted article text as a message in the WeChat group chat, if the Chinese account did not receive it, then we flag the message text as containing one or more keyword combinations which trigger text censorship. Figure 2 shows an example of the censorship happening in one such group chat. We then perform further tests to reduce the text of the article text to the minimum number of characters required to trigger censorship. Finally, we group each resulting keyword combination into content categories based on the underlying context.

Discovering Keyword Censorship

We ran our testing from January 1 to February 15, 2020, from a University of Toronto network. Our sample of articles to test were extracted from Chinese state media, Chinese-language news aggregators that post trending articles published by state and commercial media in China, and news websites based in Hong Kong and Taiwan (see Appendix A for a list of sources). In previous work, we found that extracting article text from these news sources is an effective way to discover censored keyword combinations related to events over a defined time period.

Results

In this section, we present what COVID-19-related content is censored on YY and WeChat.

Censorship on YY

On December 31, 2019, a day after Dr. Li Wenliang and seven others warned of the COVID-19 outbreak in WeChat groups, YY added 45 keywords to its blacklist, all of which made references to the then unknown virus that displayed symptoms similar to SARS (the deadly Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome epidemic that started in southern China and spread globally in 2003).

Among the 45 censored keywords related to the COVID-19 outbreak, 40 are in simplified Chinese and five in traditional Chinese. These keywords include factual descriptions of the flu-like pneumonia disease, references to the name of the location considered as the source of the novel virus, local government agencies in Wuhan, and discussions of the similarity between the outbreak in Wuhan and SARS. Many of these keywords such as “沙士变异” (SARS variation) are very broad and effectively block general references to the virus.

Table 1 provides a selection of censored keywords in this category.

| Language | Keyword | English Translation | Date Added |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉不明肺炎 | Unknown Wuhan pneumonia | 2019-12-31 |

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉海鲜市场 | Wuhan seafood market | 2019-12-31 |

| Simplified Chinese | 沙士变异 | SARS variation | 2019-12-31 |

| Traditional Chinese | 爆發sars疫情 | SARS outbreak in Wuhan | 2019-12-31 |

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉卫生委员会 | Wuhan Health Committee | 2019-12-31 |

| Simplified Chinese | p4病毒实验室 | P4 virus lab | 2019-12-31 |

A selection of keywords added to YY’s blacklist on December 31, 2019

YY removed five of the 45 keywords on February 10, 2020. Table 2 shows the five keywords that were removed from YY’s blacklist.

| Language | Keyword | English Translation | Date Removed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 病毒感染 | Virus infected | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 疫情事件 | Epidemic | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 肺炎病人 | Pneumonia patient | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉流行肺炎 | Wuhan pneumonia epidemic | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 非典性肺炎 | Atypical pneumonia | 2020-02-10 |

Keywords removed from YY’s blacklist on February 10, 2020

We cannot be certain why these keywords were removed from the blacklist. However, the removed keywords had a lower average keyword length (4.29) than the remaining (5.9), suggesting that the removed words were shorter and more broad. YY operators may have felt that some blacklisted keywords were overly broad, resulting in a substantial degradation in user experience by filtering many nonsensitive conversations about the COVID-19 outbreak.

Public information shows that there were 104 cases of COVID-19 infections as of December 31, 2019. Yet, the full scope of the outbreak, including the ability of the virus to transmit person-to-person, was not disclosed to the public in China until around January 20, 2020. Our results show that at least one Chinese social media platform began blocking COVID-19 content three weeks before this official announcement, which strongly suggests that social media companies came under government pressure to censor information at early stages of the outbreak.

Censorship on WeChat

Between January 1 and February 15, 2020, we found 516 keyword combinations directly related to COVID-19 that were censored in our scripted WeChat group chat. The scope of keyword censorship on WeChat expanded in February 2020. Between January 1 and 31, 2020, 132 keyword combinations were found censored in WeChat. Three hundred and eight-four new keywords were identified in a two week testing window between February 1 and 15.

Keyword combinations include text in simplified and traditional Chinese. We translated each keyword combination into English and, based on interpretations of the underlying context, grouped them into content categories.

Censored COVID-19-related keyword combinations cover a wide range of topics, including discussions of central leaders’ responses to the outbreak, critical and neutral references to government policies on handling the epidemic, responses to the outbreak in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau, speculative and factual information on the disease, references to Dr. Li Wenliang, and collective action.

Central Leadership

We found that 192 keyword combinations reference China’s highest-level leaders and their roles in handling the outbreak. The majority of the keyword combinations in this category reference President Xi Jinping (87%). The remaining keyword combinations (25 in total) reference the names of other central government and Party leaders including Premier Li Keqiang, Vice Premier Sun Chunlan, and the Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China as a collective agency.

While a number of these keyword combinations are critical in nature (e.g., “亲自 [+] 皇上,” by someone + emperor), criticizing or alluding to the central leadership’s inability or inaction in dealing with COVID-19 (e.g., “习近平 [+] 形式主义 [+] 防疫,” Xi Jinping + formalism + epidemic prevention), many of them refer to leadership in a neutral way (e.g., “肺炎 [+] 李克强 [+] 武汉 [+] 总理 [+] 北京,” Pneumonia + Li Keqiang + Wuhan + Premier + Beijing). Eight of the Xi-related keyword combinations reference his whereabouts during the outbreak, such as whether he had been to Wuhan city.

Table 3 shows examples of censored keyword combinations in this category.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 习近平到武汉 | Xi Jinping goes to Wuhan | 2020-02-04 |

| Simplified Chinese | 某人+亲自 | Someone + Himself

[“someone” is a code referencing Xi Jinping] | 2020-02-03 |

| Simplified Chinese | 到+雷神山+总书记 | Goes to + Leishen shan (hospital) + (CCP) General Secretary | 2020-02-05 |

| Simplified Chinese | 总书记+红十字会+亲自 | (CCP) General Secretary + Red Cross + Himself | 2020-02-13 |

| Traditional Chinese | 疫情+肺炎+習近平+中央 | Epidemic + Pneumonia + Xi Jinping + Central | 2020-02-12 |

| Traditional Chinese | 習近平+疫情+政府+負面 | Xi Jinping + Epidemic + Government + Negative | 2020-02-10 |

| Traditional Chinese | 疫情+習主席+凝聚力 | Epidemic + Chairman Xi + Unity | 2020-02-12 |

| Simplified Chinese | 习近平+疫情蔓延 | Xi Jinping + Epidemic spread | 2020-02-04 |

| Simplified Chinese | 习近平+武汉+委托+李克强 | Xi Jinping + Wuhan + Assign + Li Keqiang | 2020-02-04 |

| Simplified Chinese | 肺炎+李克强+武汉+总理+北京 | Pneumonia + Li Keqiang + Wuhan + Premier + Beijing | 2020-02-13 |

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢+肺炎+病毒+李克強 | Wuhan + Pneumonia + Virus + Li Keqiang | 2020-02-12 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to COVID-19 and China’s central leadership

Government Actors and Policies

We found 138 keyword combinations that include references to government actors and/or government policies involved in the handling of COVID-19.

Of these keyword combinations, 39% are critical in nature, blaming central or local governments as well as government-related agencies for mishandling or covering up the outbreak (e.g., “武漢 [+] 隱瞞疫情,” Wuhan + Conceal Epidemic). Among these critical keyword combinations, a few reference the Red Cross Society of Hubei province, which has come under fire for demanding social donations of medical supplies be centralized to the Red Cross itself, but then distributing the supplies poorly and unfairly.

Some keyword combinations include sarcastic homonyms or word play related to COVID-19 (e.g., “官狀病毒,” literally “virus of officialdom,” a homonym of the Chinese phrase for coronavirus “冠状病毒”).

Table 4 shows examples of censored keyword combinations in this category.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 扒一扒武汉病毒所+所长的成功史 | Muckraking Wuhan Virus Lab + Successful history of lab director | 2020-02-14 |

| Traditional Chinese | 地方官+疫情+中央+隱瞞 | Local authorities + Epidemic + Central (government) + Cover-up | 2020-02-13 |

| Traditional Chinese | 舉行+批評中國+兩會期間+隱瞞 | Hold + Criticize China + During two annual meetings + Cover-up | 2020-02-13 |

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢+中共+危機+北京 | Wuhan + CCP + Crisis + Beijing | 2020-02-11 |

| Traditional Chinese | 共产党+肺炎+表现+统治 | Communist Party + Pneumonia + Demonstrate + Rule | 2020-02-05 |

| Simplified Chinese | 疫情+红会+4+政府+湖北 | Epidemic + Red Cross Society + 4 + Government + Hubei | 2020-02-04 |

| Simplified Chinese | 中国共产党+最大的威胁+这个时代 | CCP + Biggest threat + The era | 2020-02-05 |

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢+明明+病毒+人傳人 | Wuhan + Obviously + Virus + Human-to-human transmission | 2020-02-12 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat criticizing government actors or policies regarding COVID-19

A further 51 keyword combinations make neutral references to government policies that had already been confirmed by the authorities or reported by news media accessible in mainland China (e.g., “集中隔离 [+] 武汉封城,” Centralized Quarantine + Wuhan Lockdown).

Keyword combinations include references to domestic policies, including the decision made by Chinese authorities to lock down Wuhan beginning on January 23, 2020 (“封城 [+] 武汉 [+] 中央 [+] 当局,” lockdown + Wuhan + Central government + authorities), a court notice warning that spreading COVID-19 on purpose may violate China’s criminal law and be punishable by death (“傳播 [+] 判死刑 [+] 危害公共安全 [+] 病毒,” spread + sentenced to death + endanger public safety + virus), and official statements on the importance of guiding public opinion during the crisis (“舆论引导 [+] 政治局 [+] 集中统一领导 [+] 常委会,” public opinion guidance + Politburo + centralized leadership + standing committee).

Many of the keyword combinations in this category were very broad. For example, “美国疾控中心 [+] 冠状病毒” (US Centers for Disease Control + coronavirus) refers to the virus as well as a source of information about it. The keyword combination “为辅 [+] 西医 [+] 冠状病毒” (supplementary + Western medicine + coronavirus) refers to the virus as well as a treatment modality for it.

Additionally, 33 keyword combinations reference China’s foreign policies and international relations related to COVID-19. One of the censored keyword combinations (“1月3日起 [+] 30次向美方通报 [+] 疫情信息,” Since January 3 + notified US of + epidemic) was extracted from the notes of Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s daily briefing on February 3, 2020, in which Hua said China had “notified the US of the epidemic and our control measures altogether 30 times since January 3.” Hua’s briefing shows that authorities had delayed informing the Chinese public of the epidemic as the full scope of the epidemic was not made public until January 20, 2020. Moreover, whistle-blowers were punished by local authorities for “spreading rumours” and “disturbing social order” in early January, which was around the same time China alerted the US of the epidemic according to Hua.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 美国疾控中心+冠状病毒 | US Centers for Disease Control + Coronavirus | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 菲律宾总统府感谢中国捐赠菲律宾 | Filipino President office thank China for donating the Philippines | 2020-02-14 |

| Simplified Chinese | 全面接管+10号疫情不好转+解放军 | Take over + (If) epidemic doesn’t get better by the 10th + People’s Liberation Army | 2020-02-14 |

| Traditional Chinese | 網上教學+大力+推進 | Online teaching + Strongly + Promote | 2020-02-11 |

| Traditional Chinese | 封城+部隊 | Lockdown of a city + Military | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 政府+做出+测序+病毒 | Government + Male + Testing + Virus | 2020-02-05 |

| Simplified Chinese | 为辅+西医+冠状病毒 | Supplementary + Western medicine + Coronavirus | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 省委书记+通报+专家组+病毒 | Provincial party secretary + Announced + Expert team + Virus | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 断崖式下跌+疫情防控 | A cliff-like drop + Epidemic prevention | 2020-02-13 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat making neutral reference to government actors or policies regarding COVID-19

COVID-19 in Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan

We found that 99 keyword combinations reference COVID-19 in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau.

Within this category, 68% of keyword combinations focus on Hong Kong with references to local politics and public sentiment surrounding the Chief Executive of the city, Carrie Lam. The majority of keyword combinations referencing Lam criticize her administration’s failure to respond to the health crisis (e.g., “民心背離 [+] 供應不足 [+] 積極搜購,” lost public trust + in short supply + proactively search and purchase (masks)) and on local protests demanding the closure of the borders between Hong Kong and mainland China (e.g., “封關 [+] 林鄭 [+] 醫護 [+] 香港 [+] 罷工,” close border + Carrie Lam + Medical workers + Hong Kong + go on strike). On February 3, 2020, thousands of Hong Kong medical workers went on strike to demand Carrie Lam immediately close the city’s border with mainland China to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 發起罷工+五大訴求+員工陣線 | Initiated strike + Five demands + (Hospital Authority) Employees Alliance | 2020-02-12 |

| Traditional Chinese | 香港+林鄭+呼籲+病毒 | Hong Kong + Carrie Lam + Appeal + Virus | 2020-02-10 |

| Traditional Chinese | 香港+港府+衞生防護+港人 | Hong Kong + Hong Kong government + Health prevention + Hong Kong people | 2020-02-10 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to COVID-19 and Hong Kong

Meanwhile, 16 keyword combinations reference COVID-19, Taiwan, and general tensions in the cross-strait relationship. Facing the potential of a COVID-19 outbreak, authorities in Taiwan announced a month-long export ban on surgical and N95 masks on January 24, 2020. While the export restrictions do not target mainland China, some criticized the ban as lacking compassion and empathy.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 大陸+台灣+病毒+外交部 | Mainland + Taiwan + Virus + Ministry of Foreign Affairs | 2020-02-13 |

| Traditional Chinese | 口罩+台灣+出口+國家 | Masks + Taiwan + Export + Country | 2020-02-12 |

| Traditional Chinese | 口罩+台灣+政府+中國大陸 | Masks + Taiwan + Government + Mainland China | 2020-02-09 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to COVID-19 and Taiwan

A single keyword combination references response to COVID-19 in Macau (see Table 8).

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 澳門+政府+戴口罩 | Macau + Government + Wear masks | 2020-02-10 |

A keyword combination censored on WeChat related to COVID-19 and Macau

Speculative Content of COVID-19

A further 38 keyword combinations include speculative or unconfirmed information related to the outbreak, such as discussions of whether the actual death toll was higher, the source of the virus, and whether the epidemic had gotten out of control. Table 9 shows examples of censored keyword combinations in this content category.

Authorities in China have vowed to rid the Internet of rumours about the epidemic that they claim will cause public fear and chaos. Similarly, the WHO has stated the COVID-19 outbreak has been accompanied by an “infodemic” where there is an “over-abundance” of accurate and inaccurate information on social media. The WHO has reportedly worked with WeChat to add a news feed featuring correct information translated into Chinese by the WHO.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢肺炎疫情失控 | Wuhan pneumonia epidemic out of control | 2020-02-12 |

| Simplified Chinese | 死亡病例+肺炎+死亡人數 | Death case + Pneumonia + Death toll | 2020-02-10 |

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢+感染+十幾萬 | Wuhan + Infection + Tens of thousands | 2020-02-10 |

| Simplified Chinese | 上海+背景+药物+病毒 | Shanghai + Background + Drug + Virus | 2020-02-02 |

| Traditional Chinese | 毒城+武漢 | Poisonous City + Wuhan | 2020-02-12 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to speculative information about COVID-19

Factual Information and Discussions of COVID-19

A further 23 keyword combinations include factual information related to COVID-19. These keyword combinations were largely extracted from news articles accessible in mainland China, which means this information had been sanctioned by state authorities.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉+发生+人传人+病毒 | Wuhan + Happens + People-to-people transmission + Virus | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 肺炎+疾病预防控制+病毒+医学期刊 | Pneumonia + Disease control and prevention + Virus + Medical journal | 2020-02-14 |

| Simplified Chinese | 有关+疾病控制+旅行限制+病毒 | Relevant + Disease control + Travel ban + Virus | 2020-02-05 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to factual information about COVID-19

Dr. Li Wenliang

References to Dr. Li Wenliang account for 19 censored keyword combinations. Dr. Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist in Wuhan, was among a group of medical professionals that issued the first warnings about the outbreak in WeChat group chats on December 30, 2019, a day before the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission first publicly recognized the disease. Li was later diagnosed with COVID-19 himself and died of the disease around February 6, 2020, at the age of 33.

The story of Li Wenliang has triggered sympathy and public outcry in China. Four days after Li sent the message in WeChat, he was summoned to the local police security department where he was told to sign a letter, in which he was accused of “making false comments” that had “severely disturbed the social order.” The local police security department also released a public statement reprimanding “eight lawbreakers” for “distributing and forwarding false information online” related to the pneumonia-like diseases. After the passing of Li Wenliang, Chinese citizens mourned the whistleblower and criticized the authorities for his mistreatment online and offline. Li Wenliang’s mourners created the hashtag #wewantfreedomofspeech# on Sina Weibo, the largest microblogging platform in China.

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 疫情+颜色革命+李文亮 | Epidemic + Colour revolution + Li Wenliang | 2020-02-11 |

| Traditional Chinese | 聲音+人傳人+李文亮 | Voice + People-to-people transmission + Li Wenliang | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 疫情+病毒+李文亮+中央 | Epidemic + Virus + Li Wenliang + Central government | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 冠状病毒+人传人+李文亮 | Coronavirus + People-to-people transmission + Li Wenliang | 2020-02-09 |

| Simplified Chinese | 监察委+确诊+李文亮 | National Supervisory Commission + Confirmed infection + Li Wenliang | 2020-02-09 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to Dr. Li Wenliang

Collective Action

Finally, seven keyword combinations include calls for petitions and public mobilization. This content primarily references petitions in mainland China to hold governments accountable for their actions and inaction during the COVID-19 outbreak. Borrowing from slogans of protests in Hong Kong, some citizens have come up with different versions of the “Five Demands” to combat the COVID-19 in mainland China such as “quarantine infected zones,” “dismiss incompetent officials,” and “set up independent investigation committee.”

| Language | Keyword Combination | English Translation | Date Tested |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 武漢+光復 | Wuhan + Liberate | 2020-02-12 |

| Simplified Chinese | 湖北+五大诉求 | Hubei + Five demands | 2020-02-11 |

| Simplified Chinese | 武汉+五大诉求 | Wuhan + Five demands | 2020-02-11 |

A selection of keyword combinations censored on WeChat related to COVID-19 and collective action

Limitations

The different ways that WeChat and YY perform censorship pose unique methodological challenges. In the case of YY, where the censorship rules are on the client-side (i.e., included in the code of the application) it is possible to reverse engineer the application and collect keyword lists that provide an exhaustive, unbiased view into what is censored on YY and at exactly what time keywords were added or removed from the blacklist. This comprehensive view is not possible with systems that perform censorship on the server-side, such as WeChat, since the censorship rules exist on a remote server and can only be inferred through sample testing. The results of sample testing are inherently limited as they are only as accurate as the overlap between the sample and the actual content filtered.

In our tests, we made efforts to build a diverse sample that included articles from news groups in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau, which may include criticism of the Chinese government, and official mainland China media, which is subject to state editorial and censorship. However, the script we used to parse articles from these sources and input them into our WeChat testing system did not proportionally sample articles from these websites. It downloaded more news articles from Chinese state media than from other sources, which may have affected the type of censored content we observed. For instance, the relatively low volume of censored critical content might be an accurate representation of how WeChat targets discussions of government actors or may be a result of primarily testing news articles from Chinese state media. Similarly, the small number of collective action-related keyword combinations may be an accurate representation of how WeChat targets COVID-19 content on the platform or may reflect bias in our news sources, which are unlikely to include user-generated content pertaining to collective action.

Despite these limitations, our results provide a baseline understanding of COVID-19 content that is censored on WeChat, which can be further refined in future research.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our findings show that information on COVID-19 is being tightly controlled on Chinese social media. Censorship of COVID-19 content started at early stages of the outbreak and continued to expand blocking a wide range of speech, from criticism of the government to officially sanctioned facts and information.

Leaked directives and previous research show that Chinese social media companies receive greater government pressure around critical or sensitive events. While it is not known what specific directives on COVID-19 may have been sent down from the government to social media companies, our research suggests that companies received official guidance on how to handle it as early as December 2019 when the spread of the disease was first made public. Just a day after Dr. Li Wenliang and other medical professionals tried to inform the public about the outbreak, YY began to censor information related to the epidemic on its platform. WeChat restricted content pertaining to government criticism, speculation about the COVID-19 epidemic, and collective action, factual information related to COVID-19 and neutral references to government policies responses outbreak.

What explains these broad restrictions? Analyzing how censorship decisions are made on Chinese social media requires consideration of both the role of government authorities and the companies that manage and operate the platforms. Censorship of domestic social media platforms in China is undertaken through a system of intermediary liability or “self-discipline” in which companies are held liable for content on their platforms. Companies are expected to invest in technology and personnel to carry out content censorship according to government regulations. Self-discipline works as a means for the government to push responsibility of information control to the private sector.

With respect to the role of the Chinese government, the COVID-19 censorship may be a result of specific government directions to control the narrative and manage public sentiment. Since the outbreak, government officials and Party leaders have been stressing the importance of “public opinion guidance” and “leadership over news and propaganda.” Limiting the dissemination of speculative information about the disease may be an attempt to reduce public fear, for example. On the other hand, censoring keywords critical of central leadership and government actors may be an effort to avoid embarrassment and maintain a positive image of the government.

The roles and responsibilities that private companies have in China to manage their platforms may help explain the censorship of neutral references and factual information. This censorship may be a result of companies over-censoring in order to avoid official reprimands for failing to prevent the distribution of “harmful information” including “inappropriate comments and descriptions of natural disasters and large-scale incidents.”

Censorship of the COVID-19 outbreak is troubling, and shows the need for thorough analysis of the effects of information control during a global public health crisis. Countering misinformation and uninformed speculation related to the epidemic may help keep public fear in check and remove information that would mislead people about how best to protect themselves. However, restricting general discussions and factual information has the opposite effect and limits public awareness and response.

In previous work, we observed that Chinese social media companies lifted censorship of sensitive content as the corresponding events changed course or faded into the past. In the case of COVID-19, social media platforms may unblock certain content as the event develops. In this study, we have observed YY unblocking keywords, and, although we did not measure for WeChat unblocking, it is reasonable to assume that WeChat has also unblocked some keyword combinations as it continues to block others. As the COVID-19 outbreak continues, it is important to continue tracking how information is controlled online and the wider consequences of these controls.

Data

Keyword data available on Github.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by Open Society Foundations.

Graphics design by Mari Zhou. Special thanks to Ron Deibert, John Scott-Railton, and Miles Kenyon for edits and comments.

Appendix A: WeChat Testing News Sources

List of news sources monitored for WeChat testing.

| Name | Note |

|---|---|

| ifeng | Mainland China-based news aggregator |

| QQ news | Mainland China-based news aggregator |

| Sohu News | Mainland China-based news aggregator |

| am730 | Cantonese newspaper published in Hong Kong |

| Apple Daily | Hong Kong-based tabloid-style newspaper |

| Bastille Post | Hong Kong-based online media |

| ET Net | Hong Kong-based media |

| Hong Kong Economic Journal | Hong Kong-based media |

| Hong Kong Economic Times | Financial daily newspaper in Hong Kong |

| Hong Kong Free Press | English news website based in Hong Kong |

| Independent Media Hong Kong | An independent online media platform in Hong Kong |

| Ming Pao | Hong Kong-based Chinese-language newspaper |

| The News Lens | Bilingual website based in Taiwan and Hong Kong |

| Oriental Daily News | Chinese-language newspaper in Hong Kong |

| Passion Times | Online website run by Hong Kong activist group Civic Passion |

| RTHK | Hong Kong-based radio and news site |

| South China Morning Post | Hong Kong English-language newspaper |

| Sing Tao Daily | Chinese-language newspaper in Hong Kong |

| Sky Post | Hong Kong-based newspaper |

| Ta Kung Pao | Hong Kong-based newspaper |

| The Standard | English newspaper in Hong Kong |

| Wen Wei Po | Hong Kong-based Chinese language newspaper |

| China Central Television | Beijing-based state media |

| China Economy | News site based in mainland China |

| China Net | State media in mainland China |

| China Daily | English-language daily newspaper published in mainland China |

| China News Service | State-owned news agency in mainland China |

| China National Radio | State-owned radio and news site in mainland China |

| Guangming Online | State-owned news site in mainland China |

| People’s Daily | Official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China |

| Xinhua News Agency | Official state-run press agency of China |