WeChat Surveillance Explained

FAQ

On May 7 2020, the Citizen Lab published a report that documents how WeChat (the most popular social app in China) conducts surveillance of images and files shared on the platform and uses the monitored content to train censorship algorithms. This document provides a summary of the research findings and questions and answers from the research team.

- Key Takeaways

- Questions and Answers from the Research Team

- How does censorship work on WeChat?

- What is the difference between China- and non-China-registered accounts?

- How did you discover that non-China-registered accounts were being monitored?

- How are sensitive files analyzed, flagged, and stored by WeChat?

- MD5 hashes are used by WeChat to quickly identify content once it has been flagged as sensitive by WeChat. What is an MD5 hash?

- What are the limitations of this research?

- What do these findings mean for non-China-registered users?

- Do these findings mean that the Chinese government is surveilling WeChat’s international users?

- Don’t all social media companies perform some type of content monitoring? How is what WeChat is doing different?

- How do these findings add to our understanding of digital censorship in China?

- What is the scale of censorship in China?

- What are the potential legal issues around these findings? Aren’t privacy policies supposed to warn users about this type of monitoring?

- How is this study related to previous Citizen Lab research that documented censorship of COVID-19 content on WeChat?

- What are your plans for future research?

- Background on WeChat and Previous Research

On May 7 2020, the Citizen Lab published a report that documents how WeChat (the most popular social app in China) conducts surveillance of images and files shared on the platform and uses the monitored content to train censorship algorithms. This document provides a summary of the research findings and questions and answers from the research team.

Key Takeaways

WeChat surveils non-China-registered accounts and uses messages from those accounts to train censorship algorithms to be used against China-registered accounts.

In previous research, we found that censorship on WeChat is only enabled for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. WeChat users outside of China may think that WeChat’s political censorship and surveillance system does not affect them. However, in new research we show that files and images shared by WeChat users with accounts outside of China are subject to political surveillance, and this content is used to train and build up the censorship system that WeChat uses to censor China-registered users. Our technical methods can only tell us if files and images shared on WeChat are under surveillance. We don’t know yet if chat message text is under similar surveillance. In the meantime, users should be aware that this is a possibility.

Both the monitoring and censorship happen in secret, without transparency to users.

Our research reveals that content surveillance is applied to both China-registered accounts as well as to non-China-registered accounts. Content surveillance between users of accounts registered outside of China is functionally undetectable.

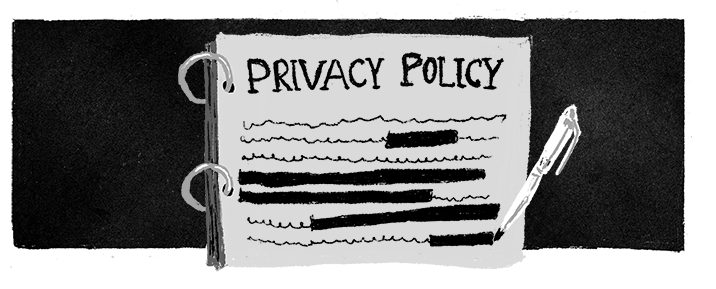

None of WeChat’s public-facing policy documents, personal data access requests processes, or privacy officers communicated that the company is conducting this surveillance.

We analyzed WeChat’s public-facing policy documents, made personal data access requests, and sent detailed questions to Tencent data protection representatives. We used these methods to assess if they could reveal or explain the surveillance practices we detected, and whether WeChat representatives would explain the company’s practices when directly asked about them. None of these methods provided a clear rationale or description of the surveillance that we detected in the course of our experiments.

Questions and Answers from the Research Team

How does censorship work on WeChat?

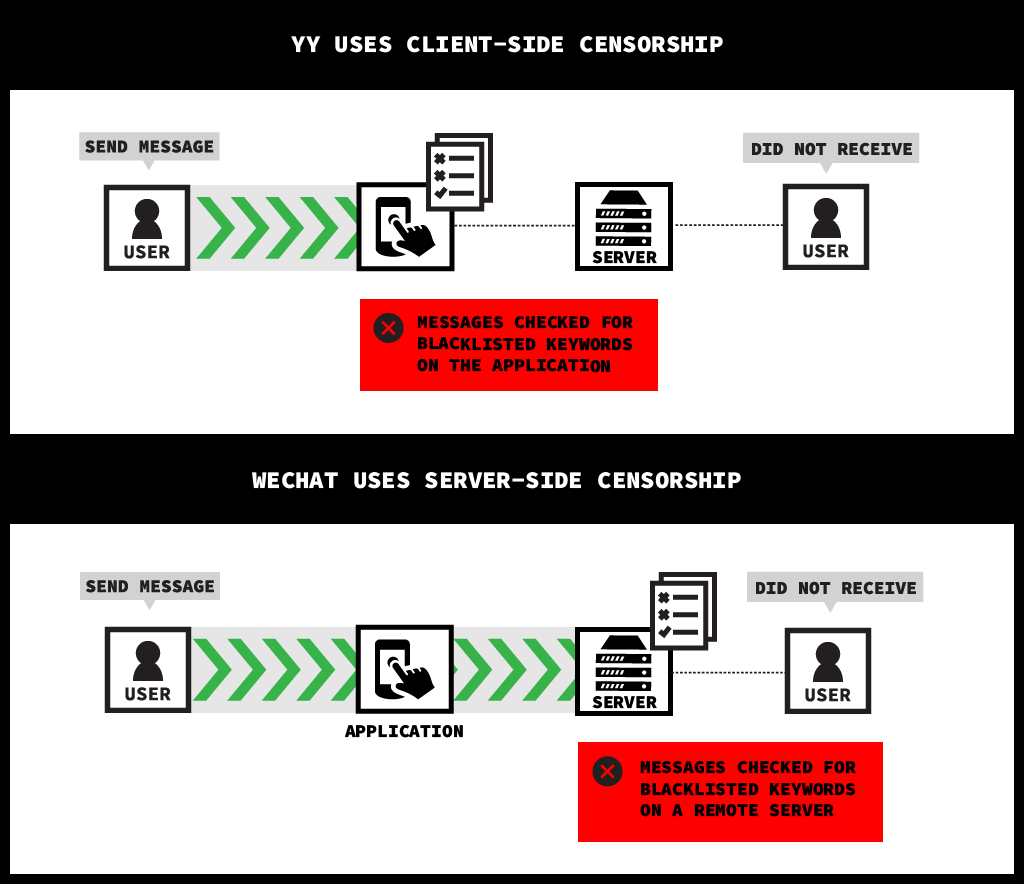

In previous work, we found that WeChat enables keyword and image censorship for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers.

WeChat censors content server-side, meaning that all the rules to perform censorship are on a remote server. When a message is sent from one WeChat user to another, it passes through a server managed by Tencent (WeChat’s parent company) that detects if the message includes blacklisted keywords before a message is sent to the recipient.

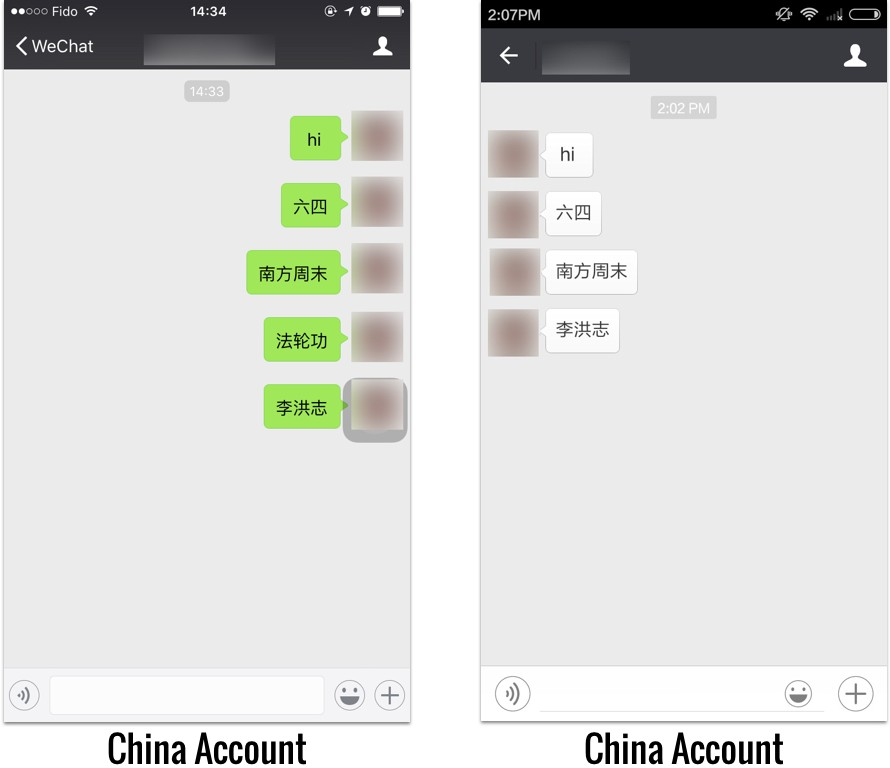

If a message is censored there is no notification given to the user sending or receiving the message. The screenshot below shows a conversation between two China-registered accounts. One user tries to send the keyword “法轮功” (falun gong) and is censored. No notification is given to either user that the message was blocked.

What is the difference between China- and non-China-registered accounts?

A China-registered account is a WeChat account that was originally registered to a mainland Chinese phone number. A non-China-registered account is any WeChat account that was not originally registered to a mainland Chinese phone number (for example an account registered to a Canadian or United States phone number). China-registered accounts are under terms of service in the jurisdiction of China (specifically Shenzhen) and are subject to censorship. Censorship persists for China-registered accounts even if the account is later associated with a phone number outside of China. Non-China-registered accounts are under terms of service outside the jurisdiction of China (specifically Singapore). While in previous research non-China-registered accounts had not been found to be under political censorship, our latest study reveals that documents and images sent from these accounts are nevertheless under political surveillance and that this content is used to invisibly build up WeChat’s censorship system for China-registered accounts.

How did you discover that non-China-registered accounts were being monitored?

Someone asked us if non-China-registered users were safe from political surveillance using WeChat as long as they weren’t talking to China-registered users. Since we knew that messages between such users were free from political censorship, we responded that “we think they are free from surveillance too.” But then we got to thinking: how can we actually measure this? Surveillance rarely occurs in a vacuum, and can be used to enable future censorship. We knew from previous work how the surveillance of images and documents is used to employ censorship in an automated fashion on WeChat. The tricky part was that non-China-registered users were not under censorship, and so to test for whether they were under surveillance we had to use two different chat conversations: a first conversation between only non-China-registered accounts for triggering surveillance and a second conversation containing a China-registered account to measure changes in censorship. When we sent politically sensitive content in the first conversation, we observed an increase in censorship in the second, revealing that the first conversation was under surveillance despite being among only non-China-registered accounts.

How are sensitive files analyzed, flagged, and stored by WeChat?

Documents are scanned for sensitive text. Images are also scanned for sensitive text, and the overall image is visually compared to a blacklist of known sensitive images. If these files are determined to be politically sensitive, then the MD5 hash (a kind of digital fingerprint) of that file is flagged, meaning that the hash is retained by WeChat and used to more efficiently censor these files in the future.

MD5 hashes are used by WeChat to quickly identify content once it has been flagged as sensitive by WeChat. What is an MD5 hash?

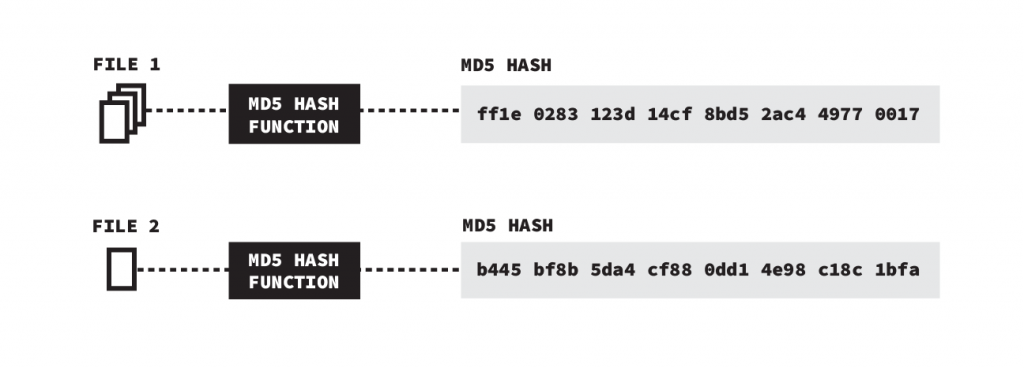

Think of it as a digital fingerprint. When files are run through the MD5 algorithm, the algorithm will generate a fingerprint, or “hash.” The hash is a short, fixed-size string of bits. In theory, it should be difficult to find or create files that will produce the same hash. However, there are vulnerabilities in the MD5 algorithm that make this reproduction easy, and we can exploit these vulnerabilities in our research. By creating two different images with the same hash — one politically sensitive and one benign — we can study how WeChat’s surveillance system works. When we send politically sensitive images between accounts registered outside China, politically benign images with the same hash are censored when sent between Chinese accounts. These benign images would not have usually been flagged as sensitive, proving that surveillance is happening in conversations between accounts registered outside China.

The diagram below shows the process of mapping a file (e.g., a document or an image) to an MD5 hash. In this example, two different images are inputted to a cryptographic hash function resulting in two unique MD5 hashes.

What are the limitations of this research?

One limitation is that our technical methods can only tell us if images and documents are under surveillance. We don’t know yet if chat message text is under similar surveillance. In the meantime users should assume that this is a possibility. Another limitation is that our research was conducted over the span of multiple months. Although we consistently observed political surveillance between non-China-registered users in our measurements during that time, we don’t know if this surveillance is something that only happened to be enabled during the time of our experiments. It’s possible that this behavior goes back years, and it may have always been present on WeChat.

What do these findings mean for non-China-registered users?

WeChat users outside of China may think that WeChat’s political censorship and surveillance systems don’t affect them. However, our research shows that by using WeChat, not only are the files and images they share under political surveillance, but their content is being used to train and build up the censorship system that WeChat uses to censor China-registered users.

Do these findings mean that the Chinese government is surveilling WeChat’s international users?

Information that is received or retained by companies based in China is subject to disclosure to the Chinese government for national security and criminal investigation purposes under China’s Cybersecurity Law. In the case of WeChat, its users in China are subject to China-based terms of service and privacy policies whereas international users are subject to terms of service and privacy policies of Singapore. Our research was motivated by a desire to understand how communications among WeChat’s international users–who are covered under by the terms of service and privacy policies published in Singapore–might be shared with WeChat offices in China or other China-based entities. In effect, we wanted to understand whether international users’ communications were protected from surveillance we have previously observed that China-based users are routinely subject to.

Our experiments reveal that communication between WeChat’s international users contribute to a censorship system that is used to censor China-registered users. Our research does not, however, reveal whether Tencent is sharing international WeChat users’ communications with the Chinese government. While our research reveals that international WeChat users are subject to content surveillance, we do not definitively know what is being surveilled, the full basis of such surveillance, or with whom surveilled data is shared.

Don’t all social media companies perform some type of content monitoring? How is what WeChat is doing different?

We say that WeChat users are under surveillance because of the type of content that is monitored — specifically, content that is politically sensitive in China. This includes content that is critical of the Chinese government or its policies, as well as content calling for government recognition of human rights, or that mourns the passing of rights activists. WeChat’s content monitoring not only differs from other platforms in what content is monitored but also in how the monitoring system is trained and selectively applied. Our research demonstrates that content sent by non-China-registered accounts is under political surveillance and used to invisibly build up WeChat’s censorship system for China-registered accounts. To our knowledge, among the monitoring systems employed by social media companies, WeChat’s surveillance system is the only system that monitors content sent by one set of users to enhance the surveillance and censorship of another set.

How do these findings add to our understanding of digital censorship in China?

To our knowledge, our research is the first of its kind that is able to provide technical evidence that WeChat — an application with a global presence — conducts surveillance on international users, and uses such surveillance to expand its censorship capabilities targeting China-registered users. Previous work on digital censorship in China focuses mainly on how censorship works and what type of content is blocked in China. Our findings are especially significant against the backdrop of the global expansion of Chinese companies, which face the balancing act of presenting a compelling experience to attract international users while controlling politically sensitive information due to regulatory pressure at home.

What is the scale of censorship in China?

China has an expansive system of censorship that includes restrictions on the Internet, applications, and media.

All Internet platforms operating in China must follow local laws and regulations regarding content controls. The companies that provide these services are held liable for content on their platforms and risk fines or losing their business license if they do not follow content regulations. What is complex about this system is that the content regulations are vaguely defined. For example, it is prohibited to post content that “disrupts social order and stability,” but it’s not clear how that determination is made. Companies may receive general directives during events that are politically sensitive to the government, but our research shows that there is no centralized list of keywords given to companies to censor. As a result, companies have to decide how to implement censorship and the specific content to censor to ensure they are within the broad guidelines and directives given by the government.

Our previous research shows that WeChat often broadly censors content during critical periods such as the passing of Liu Xiaobo, the 19th National Communist Party Congress, and most recently the coronavirus pandemic.

What are the potential legal issues around these findings? Aren’t privacy policies supposed to warn users about this type of monitoring?

App store operators such as Apple and Google require developers to include privacy policies with their apps. Many countries also have laws requiring companies to explain how they collect, process, and store data. Our research shows that the privacy policies and terms of service documents associated with WeChat International do not adequately inform users about how their data might be used.

In response to this failing, privacy regulators in some jurisdictions may have grounds to fine the company for misleading users. Depending on the regulator, fines could range from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. In other jurisdictions, such as Canada, residents could complain to their federal privacy regulator and that regulator could ultimately provide non-binding recommendations for how the company must modify its services.

App store operators, such as Apple and Google, could also take action and delist the application from their stores on the basis of misleading consumers and presenting inaccurate privacy information.

Finally, government committees might investigate how WeChat has integrated content surveillance into their application. Outcomes from such investigations could include banning certain sectors of government from using the service, or even compelling app stores to delist it based on national security threats.

How is this study related to previous Citizen Lab research that documented censorship of COVID-19 content on WeChat?

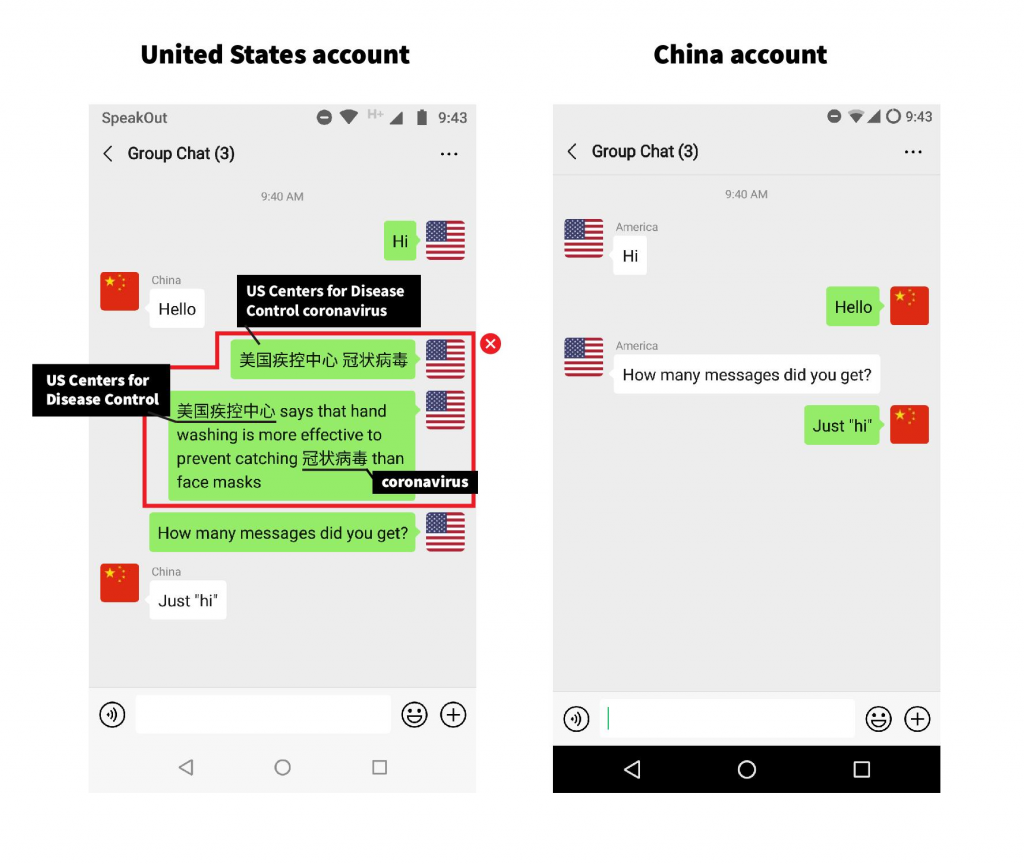

Our last report on WeChat censorship documented how COVID-19-related content was broadly censored on the platform. Because of WeChat’s “one app, two systems” censorship design, the COVID-19 censorship affects all China-registered accounts regardless of where the users are physically located.

In our latest report, we show that the scope of WeChat’s information control goes beyond China-registered accounts, and that WeChat implements surveillance among its non-China-registered accounts. Even though we did not conduct sampling and content analysis of COVID-19 content in this latest report, our study suggests that WeChat could potentially use communications among international users on the topic of COVID19 to expand its domestic censorship list.

The screenshot below shows an illustration of WeChat COVID-19 censorship we discovered in previous research. A user attempts to send messages containing the censored keyword combination “美国疾控中心” (US Center for Disease Control) and “冠状病毒” (coronavirus). The user with the China account does not receive the messages because they contain the censored keyword combination.

In this report we uncovered how WeChat implements surveillance among international users. We will continue to monitor WeChat’s surveillance of non-China-registered user’s images and documents, and we will continue to investigate how such surveillance may apply to other media such as chat message text.

What are your plans for future research?

In this report we uncovered how WeChat implements surveillance among international users. We will continue to monitor WeChat’s surveillance of non-China-registered user’s images and documents, and we will continue to investigate how such surveillance may apply to other media such as chat message text.

Background on WeChat and Previous Research

WeChat (Weixin 微信 in Chinese) is one of the most popular social media apps in China, with 1.15 billion monthly active users globally as of late 2019. Since 2013, WeChat has stopped disclosing the number of its international users. According to the most recent available data, the app has amassed over 100 million overseas registrants. The application is owned and operated by Tencent, one of China’s largest technology companies.

WeChat has a variety of features including instant messaging (e.g., one-to-one private chat, group chat), WeChat Moments (functionality that resembles Facebook’s Timeline where users can share text-based updates, upload images, and share short videos or articles with their friends), and the Public Account platform (a blogging-like platform that allows individual writers as well as businesses to write for general audiences).

Previous Citizen Lab research has shown that WeChat enables censorship of users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. Censorship on the platform is dynamic and reacts to current events such as the National Communist Party Congress and the outbreak of COVID-19.

One App, Two Systems: How WeChat Uses One Censorship Policy in China and Another Internationally

Keyword filtering on WeChat is only enabled for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers, and persists even if these users later link the account to an International number.

Censored Contagion: How Information on the Coronavirus is Managed on Chinese Social Media

The analysis of YY and WeChat indicates broad censorship of COVID-19 related content—blocking sensitive terms as well as general information and neutral references—potentially limiting the public’s ability to access information that may be essential to their health and safety.

(Can’t) Picture This: An Analysis of Image Filtering on WeChat Moments

WeChat uses two different algorithms to filter images in Moments: a visual-based algorithm that filters images that are visually similar to those on an image blacklist and an Optical Character Recognition (OCR)-based algorithm that filters images containing sensitive text.

(Can’t) Picture This 2: An Analysis of WeChat’s Realtime Image Filtering in Chats

We found that Tencent implements realtime, automatic censorship of chat images on WeChat based on what text is in an image and based on an image’s visual similarity to those on a blacklist. Tencent facilitates this realtime filtering by maintaining a hash index of MD5 hashes of sensitive image files.

Managing the Message: What you can’t say about the 19th National Communist Party Congress on WeChat

The 19th National Communist Party Congress was held from October 18-24 2017. WeChat blocked a broad range of content related to the Congress including neutral references to official party policies and ideology.

Remembering Liu Xiaobo: Analyzing censorship of the death of Liu Xiaobo on WeChat and Weibo

On July 13, 2017, Liu Xiaobo, China’s only Nobel Peace Prize winner and its most famous political prisoner died from complications due to liver cancer. He was detained in December 2008 for his participation with “Charter 08”, a manifesto that called for political reform and an end to one-party rule. Following the death of Liu Xiaobo, the scope of censorship of keywords and images on WeChat related to him expanded. Our analysis of WeChat keyword-based censorship shows that after his death messages containing his name in English and in both simplified and traditional Chinese are blocked. His death is also the first time we see image filtering in one-to-one chat, in addition to image filtering in group chats and WeChat moments.

We (can’t) Chat: “709 Crackdown” Discussions Blocked on Weibo and WeChat

This report analyzes the information control practices related to a national crackdown on Chinese rights lawyers and activists on two leading Chinese social media networks. We document search filtering on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like service, as well as keyword and image censorship on WeChat.