Running in Circles

Uncovering the Clients of Cyberespionage Firm Circles

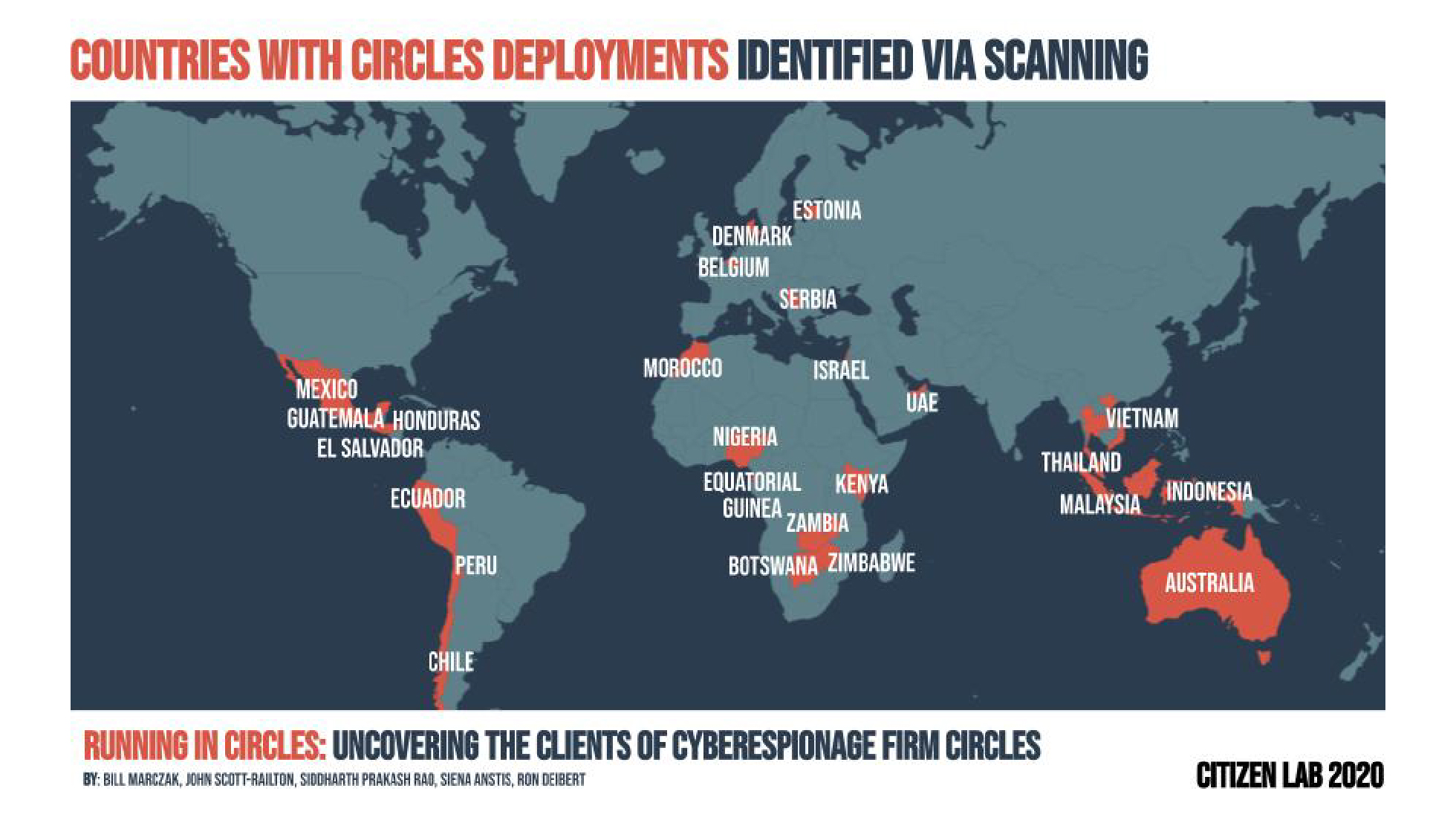

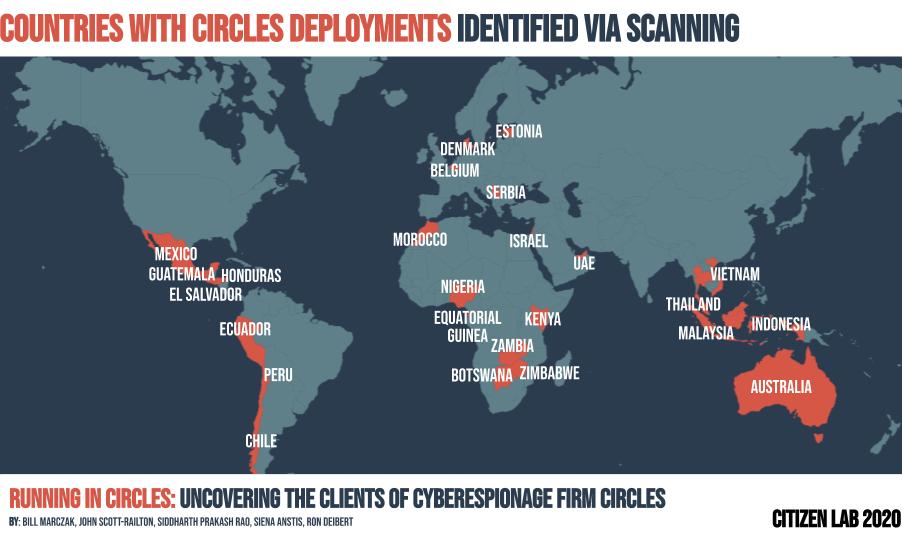

Circles is a surveillance firm that reportedly exploits weaknesses in the global mobile phone system to snoop on calls, texts, and the location of phones around the globe, and is affiliated with NSO Group, which develops the oft-abused Pegasus spyware. Using Internet scanning, we found a unique signature associated with the hostnames of Check Point firewalls used in Circles deployments, enabling us to identify Circles deployments in at least 25 countries.

Summary & Key Findings

- Circles is a surveillance firm that reportedly exploits weaknesses in the global mobile phone system to snoop on calls, texts, and the location of phones around the globe. Circles is affiliated with NSO Group, which develops the oft-abused Pegasus spyware.

- Circles, whose products work without hacking the phone itself, says they sell only to nation-states. According to leaked documents, Circles customers can purchase a system that they connect to their local telecommunications companies’ infrastructure, or can use a separate system called the “Circles Cloud,” which interconnects with telecommunications companies around the world.

- According to the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, all U.S. wireless networks are vulnerable to the types of weaknesses reportedly exploited by Circles. A majority of networks around the globe are similarly vulnerable.

- Using Internet scanning, we found a unique signature associated with the hostnames of Check Point firewalls used in Circles deployments. This scanning enabled us to identify Circles deployments in at least 25 countries.

- We determine that the governments of the following countries are likely Circles customers: Australia, Belgium, Botswana, Chile, Denmark, Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Equatorial Guinea, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Peru, Serbia, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

- Some of the specific government branches we identify with varying degrees of confidence as being Circles customers have a history of leveraging digital technology for human rights abuses. In a few specific cases, we were able to attribute the deployment to a particular customer, such as the Security Operations Command (ISOC) of the Royal Thai Army, which has allegedly tortured detainees.

1. Background

The public discussion around surveillance and tracking largely focuses on well known technical means, such as targeted hacking and network interception. However, other forms of surveillance are regularly and extensively used by governments and third parties to engage in cross-border surveillance and monitoring.

One of the widest-used—but least appreciated—is the leveraging of weaknesses in the global mobile telecommunications infrastructure to monitor and intercept phone calls and traffic.

While well-resourced governments have long had the ability to conduct such activity, in recent years companies have emerged to sell these capabilities. For example, the Guardian reported in March 2020 that Saudi Arabia appeared to be “exploiting weaknesses in the global mobile telecommunications network to track citizens as they travel around the US.” Other investigative reports indicated that journalists, dissidents, and opposition politicians in Nigeria and Guatemala were similarly targeted.

Abuse of the global telephone system for tracking and monitoring is believed to be widespread, however it is difficult to investigate. When a device is tracked—or messages intercepted—there are not necessarily any traces on the target’s device for researchers or investigators to find. Meanwhile, cellular carriers have many technical difficulties identifying and blocking abuses of their infrastructure.

SS7 Attacks

Signaling System 7 (SS7) is a protocol suite developed in 1975 for exchanging information and routing phone calls between different wireline telecommunications companies. At the time of SS7’s development, the global phone network consisted of a small club of monopolistic telecommunications operators. Because these companies generally trusted each other, SS7 designers saw no pressing need to include authentication or access control. However, the advent of telecommunications deregulation and mobile technology soon began to challenge the assumption of trust. Even so, SS7 endured, thanks to a desire to maintain interoperability with older equipment.

Because of SS7’s lack of authentication, any attacker that interconnects with the SS7 network (such as an intelligence agency, a cybercriminal purchasing SS7 access, or a surveillance firm running a fake phone company) can send commands to a subscriber’s “home network” falsely indicating that the subscriber is roaming. These commands allow the attacker to track the victim’s location, and intercept voice calls and SMS text messages. Such capabilities could also be used to intercept codes used for two-factor authentication sent via SMS. It is challenging and expensive for telecommunications operators to distinguish malicious traffic from benign behavior, making these attacks tricky to block.

Today, SS7 is predominantly used in 2G and 3G mobile networks (4G networks use the newer Diameter protocol). One of SS7’s key functions in these networks is handling roaming, where a subscriber to a “home network” can connect to a different “visited network,” such as when traveling internationally. In this situation, SS7 is used to handle forwarding of phone calls and SMS text messages to the “visited network.” Although 4G’s Diameter protocol includes features for authentication and access control, these are optional. Additionally, the need for Diameter networks to interconnect with SS7 networks also introduces security issues. There is widespread concern that 5G technology and other advances will inherit the risks of these older systems.

Circles

While companies selling exploitation of the global cellular system tend to operate in secrecy, one company has emerged as a known player: Circles. The company was reportedly founded in 2008, acquired in 2014 by Francisco Partners, and then merged with NSO Group. Circles is known for selling systems to exploit SS7 vulnerabilities, and claims to sell this technology exclusively to nation-states.

Unlike NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware, the SS7 mechanism by which Circles’ product reportedly operates does not have an obvious signature on a target’s phone, such as the telltale targeting SMS bearing a malicious link that is sometimes present on a phone targeted with Pegasus.

Most investigation of Circles has relied on inside sources and open source intelligence, rather than technical analysis. For example, a 2016 investigation by Nigerian newspaper Premium Times reported that two state governors in Nigeria acquired Circles systems and used them to spy on political opponents. In one case, the system was installed at the residence of a governor. Our scanning found two Circles systems in Nigeria (Section 4).

Documents filed as part of a lawsuit against NSO Group in Israel purport to show emails exchanged between Circles and several customers in the UAE. Most famously, the documents show Circles sending targets’ locations and phone records (Call Detail Records or CDRs) to the UAE Supreme Council on National Security (SCNS), apparently as part of a product demonstration. The emails also indicate that intercepting phone calls of a foreign target has a higher chance of success when the target is roaming.

The same documents explain some facets of how the Circles system operated. The SCNS was set to receive two separate systems: a standalone system that could be used for local interceptions and a separate system connected to the “Circles Cloud” (an entity with roaming agreements around the world) that could be used for interceptions outside of the UAE if desired.

| Circles System Component | Function |

|---|---|

| Offline, on-premises deployment | Within-country targeting |

| Circles Cloud | Global targeting & interception |

In 2015, IntelligenceOnline suggested that Circles started a bogus phone company called “Circles Bulgaria” to facilitate interceptions around the world. More recently, a 2020 report by Forensic News raised questions as to the true business of FloLive, purportedly an “IoT connectivity” company. Forensic News found that FloLive appeared to be closely associated with Circles, and suggested that the company might be a “front for the hackers and private spies behind Circles.”

There is also limited information about how the Circles system integrates with NSO Group’s flagship Pegasus spyware, though a former NSO Group employee told Motherboard that Pegasus had an “awful integration with Circles,” and that Circles had “exaggerated their system’s abilities.”

2. Fingerprinting & Scanning for Circles

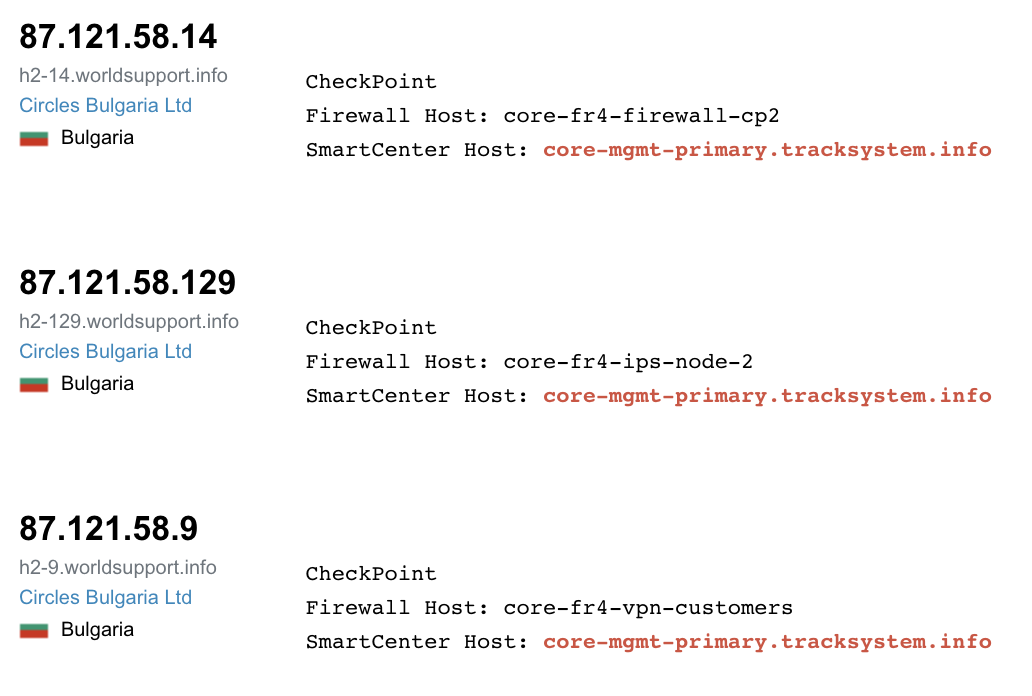

While searching Shodan, we observed interesting results in AS200068, a block of IP addresses registered to Circles Bulgaria (Figure 2). These results show hostnames of firewalls manufactured by Check Point, as well as the hostnames of the firewalls’ SmartCenter instance. SmartCenter can be used to centrally manage multiple Check Point firewalls1.

The SmartCenter hostnames in the Circles-registered AS200068 contain the domain name tracksystem.info. It seems clear that tracksystem.info is associated with Circles, as leaked documents show Circles employees communicating from @tracksystem.info email addresses. Additionally, per RiskIQ, 17 of the 37 IP addresses pointed to by tracksystem.info or its subdomains are in AS200068 as well as AS60097, also registered to Circles Bulgaria.

We searched for Check Point firewalls whose SmartCenter hostname contained tracksystem.info on Shodan, Censys, Fofa, and on Rapid7’s historical sonar-ssl dataset. We also searched for IPs that returned peculiar “random” TLS certificates2 matching the following regular expression, as we saw these certificates returned by Check Point firewalls with tracksystem.info in their SmartCenter hostnames:

/^C=[a-zA-Z0-9]{2}, ST=[a-zA-Z0-9]{3}, L=[a-zA-Z0-9]{3}, O=[a-zA-Z0-9]{4}, OU=[a-zA-Z0-9]{5}, CN=localhost$/Overall, we identified 252 IP addresses in 50 ASNs matching our fingerprints. Many had a “Firewall Host” field seemingly indicating that the systems were client systems, e.g., client-circles-thailand-nsb-node-2, though some used the word telco in place of client, and some had a generic name rather than a client name, e.g., cf-00-182-1. In cases where we identified Circles’ Check Point firewalls on a Transit/Access ISP (i.e., a non-datacenter ISP), we assumed that some agency of that country’s government was a customer of Circles.

Some of the clients that we identified have two-word nicknames, where the first word is a car brand that almost always shares the same first letter as the country or state of the apparent customer. For example, Circles firewalls whose IPs geolocate to Mexico are named “Mercedes,” those that geolocate to Thailand are named “Toyota,” those that geolocate to Abu Dhabi are named “Aston,” and those that geolocate to Dubai are named “Dutton.”

The use of car brands to refer to clients was first reported by Haaretz, though the report indicated that this was an NSO Group practice, as opposed to Circles. Haaretz reported the following codenames: Saudi Arabia is “Subaru,” Bahrain is “BMW,” and Jordan is “Jaguar.” Our scans did not reveal any Check Point firewalls linked to Circles with the names Subaru or Jaguar, though we did identify firewalls with the name “BMW” located in Belgium.

3. A Global List of Circles Deployments

From the 252 IP addresses we detected in 50 ASNs, we identified 25 governments that are likely to be Circles customers. We also identified 17 specific government branches that appear to be Circles customers, based on WHOIS, passive DNS, and historical scanning data from Check Point firewall IPs or their neighbours.

Australia, Belgium, Botswana (Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services), Chile (Investigations Police), Denmark (Army Command), Ecuador, El Salvador, Estonia, Equatorial Guinea, Guatemala (General Directorate of Civil Intelligence), Honduras (National Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence), Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico (Mexican Navy; State of Durango), Morocco (Ministry of Interior), Nigeria (Defence Intelligence Agency), Peru (National Intelligence Directorate), Serbia (Security Information Agency), Thailand (Internal Security Operations Command; Military Intelligence Battalion; Narcotics Suppression Bureau), the United Arab Emirates (Supreme Council on National Security; Dubai Government; Royal Group), Vietnam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

While our analysis yielded country results with high confidence, our efforts to determine the customer identity have, in some cases, a lower degree of confidence.

We also found evidence of at least four systems that we were unable to connect to a particular country (Appendix A).

4. Spotlight on Concerning Circles Deployments

Our research identified deployments in 25 countries. In several cases, we were able to go further and identify technical elements pointing to a particular government customer with varying degrees of certainty. Troublingly, in a number of these cases, the government as a whole, or the government client in particular, have a history of misuse of surveillance technologies and human rights abuses. While several cases are highlighted here, Appendix A lists the additional deployments found by our fingerprinting.

Botswana

We identified two Circles systems in Botswana: an unnamed system and a system named Bentley Bullevard that appears to be operated by Botswana’s Directorate of Intelligence and Security Service (DISS), as TLS certificates used on the Check Point firewalls were signed by a self-signed TLS certificate for “CN=sid.org.bw” which is a domain name used by the Directorate of Intelligence and Security. The DISS is sometimes referred to as the “Directorate of Intelligence and Security” (DIS).

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Dates Active | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bentley Bullevard | Directorate of Intelligence and Security Service (DISS) | 2015/6/1 – Present | 129.205.243.1 – 3 129.205.243.60 – 62 41.79.138.17 – 19 |

| 2015/6/1 – 2020/9/10 | 168.167.45.100 – 102 |

Surveillance Abuses in Botswana

There are multiple recent reports of the abuse of surveillance equipment in Botswana to suppress reporting and public awareness of governmental corruption. In 2014, it was reported that the DISS participated in using surveillance and jamming technology developed by Elbit Systems to conduct “electronic warfare” against the media. In addition, the DISS has reportedly engaged in attempts to compromise the privacy of relationships between sources and reporters.

Chile

Our scanning identified what appeared to be a single Circles system in Chile, codename Cadillac Polaris. The system appears to be operated by the Investigations Police of Chile (PDI), as the Check Point firewalls identify the client as “Chile PDI.” The PDI is Chile’s main law enforcement agency. The Chile PDI was also a customer of Hacking Team’s Remote Control System (RCS) spyware, although they claimed that the spyware was only used for prosecuting crimes with prior judicial authorization.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Dates Active | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadillac Polaris | Investigations Police of Chile (PDI) | 2015/9/12 – Present | 186.103.207.10 – 12 |

Surveillance Abuses in Chile

Between 2017 and 2018, Chile’s other major national police agency, the Carabineros, reportedly illegally intercepted the calls, WhatsApp chats, and Telegram messages of multiple journalists. Chilean police also intercepted the communications of Indigenous Mapuche leaders and cited intercepted chats to justify the arrests. However, officials were later prosecuted for planting false evidence on the leaders’ phones.

Guatemala

We identified a single Circles system in Guatemala, Ginetta Galileo. The system appears to have been operated by the General Directorate of Civil Intelligence (DIGICI), as public WHOIS information records that the firewall IPs are registered to “Dirección General de Inteligencia Civil.”

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginetta Galileo | General Directorate of Civil Intelligence (DIGICI) | 2015/6/1 – 2016/5/2 | 190.111.27.165 – 167 |

Surveillance Abuses in Guatemala

A 2018 investigation by Guatemalan newspaper Nuestro Diario found that an Israeli arms dealer sold a variety of spy tools, including NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware and a Circles system, to a secret unit within DIGICI. The unit reportedly used the equipment to conduct illegal surveillance against journalists, businesspeople, and political opponents of the government. The surveillance arose amidst extreme physical threat to members of civil society. A recent report identified over 900 attacks between 2017-2018 in Guatemala, originating from both government and non-state actors.

Mexico

We identified what appear to be ten Circles systems in Mexico. One system, Mercedes Ventura, appears to have been used by the Mexican Navy (SEMAR). All firewall IPs for the Mercedes Ventura system were in /24s with multiple other IP addresses that are pointed to by domain names and return valid TLS certificates for semar.gob.mx and other websites linked to the Mexican Navy. An unnamed system appears to have been used by the State of Durango, as one of its firewall IPs was also pointed to by dozens of subdomains of durango.gob.mx. Additional details about the Mexico Circles systems are in Appendix A.

Reporting has previously connected the Mexican government to the purchase of other SS7 surveillance equipment, such as ULIN made by Ability, as well as a system codenamed SkyLock sold by Verint Systems Inc.

Surveillance Abuses in Mexico

Mexico has an extensive history of surveillance abuses. Notably, our prior research has shown that entities within Mexico’s government serially abused NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware to target over 25 reporters, human rights defenders, and the families of individuals killed and disappeared by cartels. The pattern of abuses extends to other forms of digital surveillance.

Human rights organizations have documented that Mexico’s Navy has been responsible for civilian casualties in conflicts and human rights violations, including illegal detention, kidnapping, torture, and sexual torture. Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission recently confirmed this pattern in a recommendation.

Morocco

Our scanning identified what appeared to be a single Circles system in Morocco. The Morocco client’s IPs are in the same /27 as several websites of the Bureau central d’investigation judiciaire (BCIJ), and are in the same /26 as the website of the Moroccan Auxiliary Forces (FA). Both the FA and BCIJ are under the auspices of Morocco’s Ministry of Interior. A government agency in Morocco also appears to be a client of Circles’ affiliate NSO Group, though the identity of this Moroccan agency has not been established.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Interior | 2018/3/14 – Present | 105.145.40.27-28 |

Surveillance Abuses in Morocco

Morocco has been connected to multiple cases of surveillance abuse over the past decade, ranging from the targeting of human rights organizations with Hacking Team’s spyware to a string of more recent cases in which NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware was used to target civil society within Morocco and abroad.

Nigeria

Our scanning identified two Circles systems in Nigeria. One system may be operated by the same entity as one of the Nigerian customers of the FinFisher spyware that we detected in December 2014. The firewall IPs are in the same /27 as the IP address of the FinFisher C&C server we detected in our 2014 scans (41.242.50.50). The other client appears to be the Nigerian Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA), as its firewall IPs are in AS37258, a block of IP addresses registered to “HQ Defence Intelligence Agency Asokoro, Nigeria, Abuja.”

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nigeria Defence Intelligence Agency (DIA) | 2015/6/1 – 2017/4/25 | 196.1.133.7 – 9 | |

| Unknown FinFisher operator from December 2014. | 2015/6/1 – Present | 41.242.50.42 – 47 |

Surveillance Abuses in Nigeria

Members of civil society in Nigeria face a wide range of digital threats. A recent report by Front Line Defenders concluded that Nigeria’s government “has conducted mass surveillance of citizens’ telecommunications.” The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has also reported multiple cases of the Nigerian government abusing phone surveillance.

An investigation by Nigerian newspaper Premium Times found that Nigerian governors of Bayelsa and Delta states purchased systems from Circles to spy on their political opponents. In Delta State, Premium Times reports that the system was installed at the “governor’s lodge,” and operated by employees of the Governor, rather than police. In Bayelsa State, the governor reportedly used the Circles system to spy on his opponent in an election, as well as his opponent’s wife and aides. The investigation also found that the two Circles systems were imported without the proper authorizations from Nigeria’s Office of the National Security Adviser.

Thailand

Our scanning identified what appear to be three current clients in Thailand. The firewall IP addresses for Toyota Regency are in the same /29 as the online “War Room” of the Royal Thai Army’s Internal Security Operations Command (กองอำนวยการรักษาความมั่นคงภายใน), known as ISOC for short3. The firewall IP addresses for an unnamed system are in the same /29 as a wiki that displays the logo of the Military Intelligence Battalion (MIBn) (กองพันข่าวกรองทางทหาร), which appears to be a division of the Army Military Intelligence Command (หน่วยข่าวกรองทางทหาร), Thailand’s main military intelligence agency. The third system, Toyota Dragon, is identified by its Check Point firewalls as “Thailand NSB”, which we believe is a reference to the Narcotics Suppression Bureau.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Thai Army Military Intelligence Battalion (MIBn) | 2019/3/19 – Present | 110.164.191.212 – 214 122.154.71.180 – 182 | |

| Toyota Regency | Royal Thai Army Internal security Operations Command (ISOC) | 2016/7/12 – Present | 110.164.72.2 – 4 |

| Toyota Dragon | Royal Thai Police Narcotics Suppression Bureau (NSB) | 2015/9/12 – Present | 203.149.46.164 – 166 |

Surveillance Abuses in Thailand

Thailand has a history of leveraging a wide range of surveillance technologies to monitor and harass civil society. Previous Citizen Lab research also identified a Pegasus spyware operator active within Thailand.

The ISOC has been accused of torturing and waterboarding activists, and suing activists who allege torture at the hands of the military. Recently, disturbing reports have emerged of abductions of Thai dissidents who live outside of Thailand. In one case, three Thai dissidents living in Laos who criticized Thailand’s military disappeared, and their bodies were later discovered by a Thai fisherman. Their bodies were “disemboweled and stuffed with concrete posts” and their limbs broken. While these abductions and killings have not been conclusively attributed to the Royal Thai Army, the disappearances are reported to have happened while the leader of Thailand’s former military junta Prayut Chan-o-cha (ประยุทธ์ จันทร์โอชา) was visiting Laos. Chan-o-cha is the current Prime Minister of Thailand, as well as the director of ISOC.

United Arab Emirates

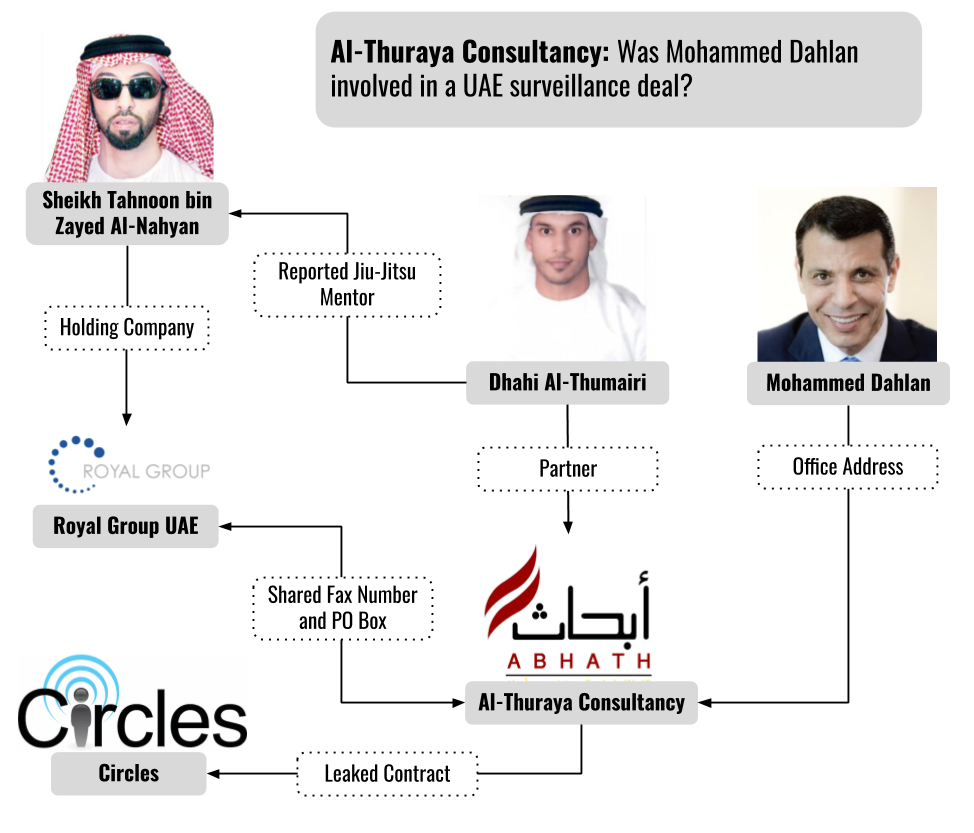

Our scanning identified what appear to be three active clients in the UAE: the UAE Supreme Council on National Security (SCNS) (المجلس الأعلى للأمن الوطني), the Dubai Government4, and a client that may be linked to both Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan’s Royal Group and former Fatah strongman Mohammed Dahlan.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Group | 2019/8/27 – Present | 94.206.102.68 – 70 | |

| Aston Andromeda | UAE Supreme Council of National Security | 2016/4/4 – Present | 213.42.167.106 – 108 91.72.225.2 – 4 |

| Dutton Dolche | Dubai Government | 2016/12/5 – Present | 151.253.54.210 – 212 91.75.44.84 – 86 |

Royal Group

We found an unnamed UAE Circles system whose Check Point firewalls were in the same /25 as websites for Royal Group companies including Mauqah Technology, which famously acquired and operated Hacking Team’s RCS spyware and, in 2012, used the system to target (among others) UAE activist Ahmed Mansoor. The command and control (C&C) server for that spyware briefly pointed to an IP address registered to Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, the chairman of Royal Group and the UAE’s now National Security Advisor. Sheikh Tahnoon was also closely linked to ToTok, a popular chat app that was banned from the Apple and Google Play stores after the New York Times reported it was linked to UAE intelligence.

A leaked 2014 invoice indicates a deal between Circles and Al Thuraya Consultancy and Researches LLC, which appears to be linked to Royal Group. Records obtained by Lebanese newspaper Al Akhbar from the Abu Dhabi Chamber of Commerce and records on companies.rafeeg.ae show that Al Thuraya shares a PO Box number (“PO Box 5151, Abu Dhabi”) and fax number (““8111112””) with Royal Group. Additionally, Al Thuraya’s commercial license shows “Dhahi Mohammed Hamad Al-Thumairi” as one of the company’s two partners. Al-Thumairi trained in jiu-jitsu with Sheikh Tahnoon’s adopted son Faisal Alketbi, received jiu-jitsu encouragement from Sheikh Tahnoon himself, and named his first son “Tahnoon.” Another of Sheikh Tahnoon’s jiu-jitsu mentees showed up in the ToTok case as the sole director of Breej Holding, the company listed as the app’s iOS developer.

Al Thuraya has been reported to be the consultancy of Mohammed Dahlan, the former head of the Palestinian Preventive Security (الأمن الوقائي), and a former member of Fatah’s Central Committee. Dahlan was ejected from Fatah in June 2011, and subsequently fled to the UAE. Indeed, the leaked 2014 invoice shows Al Thuraya’s address as “POB 128827, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates,” which is listed in WHOIS records for Dahlan’s dahlan.ps website from September 2013, and was used by Dahlan in June 2017 when he unsuccessfully sued London-based online newspaper Middle East Eye for libel. Dahlan reportedly ran an assassination program for the UAE in Yemen that targeted and killed opposition politicians. Dahlan was also reportedly involved in the recent deal that normalized relations between the UAE and Israel.

UAE Supreme Council of National Security

In a leaked 2015 exchange, a UAE Supreme Council of National Security (SCNS) official, Ahmed Ali Al-Habsi, asked Circles to intercept calls for certain phone numbers, apparently as part of a product demonstration. We found a Circles system named Aston Andromeda whose firewall IPs were registered to the same SCNS official per public WHOIS data.

The leaked documents also detail a 2016 Circles sale to the UAE National Electronic Security Authority (NESA) (الهيئة الوطنية للأمن الإلكتروني) through DarkMatter. While NESA is a subsidiary of the SCNS per UAE law, we are not sure whether the SCNS demo and DarkMatter/NESA deals are related. After Reuters’ reporting on the NESA’s Project Raven hacking campaign, the NESA was split up into several agencies, including the Signals Intelligence Agency (جهاز استخبارات الإشارة).

Surveillance Abuses in the UAE

The UAE government is a documented serial abuser of surveillance technologies to suppress dissent and persecute critical voices. Some prominent activists, like Ahmed Mansoor, an Emirati prisoner of conscience who has been imprisoned by the UAE since 2017, have been surveilled using technology from Hacking Team, Gamma Group’s FinFisher, technology developed by Project Raven, and NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

The UAE’s use of former U.S. National Security Agency employees to target the devices of dissidents, journalists, and political opponents is also well documented, as is the apparent use of this targeting to unmask and jail bloggers and others critical of the government. In some cases, the targets included Americans.

Zambia

We identified what appears to be a single Circles system in Zambia, operated by an unknown agency.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/1/30 – 2018/2/6 | 165.56.2.13 |

Surveillance Misuse in Zambia

In 2019, Zambia reportedly arrested a group of bloggers who ran an opposition news site with the aid of “a cyber-surveillance unit in the offices of Zambia’s telecommunications regulator,” which “pinpointed the bloggers’ locations” and was “in constant contact with police units deployed to arrest them.” While Circles’ solution allows governments to track phones, it is not clear if Zambia’s Circles system was used in this case.

Discussion

Circles is part of a large and growing global surveillance industry catering to government clients. Many of the government clients who appear to have acquired and/or deployed Circles technology have a dismal record of abuses of human rights and technical surveillance capabilities. Many lack public transparency and accountability, and have minimal or no independent oversight over the activities of their security agencies.

Circles: Another Industry Player Fueling the Proliferation of Unaccountable Surveillance

It is difficult to investigate and track surveillance companies like Circles that exploit flaws in the SS7 protocol. Many SS7 attacks require no engagement with targets themselves, and leave no visible artefacts on targets’ devices that may inadvertently reveal an operation. The lack of transparency from telecommunications providers about abuses also helps surveillance companies, and their customers, evade exposure, further increasing the likelihood of misuse.

The authoritarian profile of some of Circles’ apparent government clients is troubling, but not surprising. Over the past decade, the explosion of the global surveillance industry has fueled a massive transfer of spy technology to problematic regimes and security services. These customers have leveraged their newly-acquired capabilities to abuse human rights and neutralize political opposition, even beyond their borders. Circles is an especially concerning case because of their close relationship and reported integration with NSO Group, which has a notorious record of enabling surveillance abuses.

The Expanding, Unregulated Surveillance Industry

Research by the Citizen Lab and others, including Amnesty International and Privacy International, has demonstrated that the surveillance industry is poorly regulated and its products are prone to abuse. The “self-regulation” that companies claim to practice does not seem to have stemmed the growing tide of abuse cases. In a 2019 report on the surveillance industry, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression called for “an immediate moratorium on the global sale and transfer of private surveillance technology until rigorous human rights safeguards are put in place to regulate such practices and guarantee that governments and non-State actors use the tools in legitimate ways.”

As the surveillance industry continues to grow relatively unimpeded, spaces for legitimate democratic activity will continue to shrink. Governments’ ability to protect their citizens, as well as their own essential services and national security, will also continue to erode. Fixing this problem will require a direct focus on reforming the surveillance industry, including, among other steps:

- The enactment of more robust domestic, regional, and international legal frameworks—equipped with meaningful transparency, enforcement, and oversight mechanisms—to control the export and import of surveillance technology;

- Mandatory due diligence obligations on surveillance companies and enforcement mechanisms with tough penalties for breaches of such obligations; and,

- Legislative amendments to fix any legal and regulatory gaps such that parties harmed by surveillance technology can bring claims against companies for these harms.

In addition to these broader measures focused on the surveillance industry, we believe that the vulnerabilities inherent in the global telecommunications system require urgent action by governments and telecommunications providers. The global telecommunications sector provides significant opportunity for abuse by the surveillance industry and its customers in light of the continued failure of telecommunications operators and states to prevent such exploitation. In the discussion below, we set out clear actions that legislators and wireless operators must take to prevent continued exploitation and abuse.

Sounding the Alarm: A Clear and Present Threat to National Security

According to a recent study, the vast majority of telecommunications networks around the globe are vulnerable to the kind of techniques reportedly used by Circles. As has been widely reported, the industry has sought to downplay and conceal these risks. It is no surprise that reporting indicates that SS7 has been abused by countries like Saudi Arabia to target individuals around the world, including in the U.S.

A recent survey of E.U. wireless security by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) concluded that a majority of operators had security measures that could “only cover basic attacks.” Troublingly, reporting of the scale of these threats remains difficult to achieve, as SS7 abuse is not within current reporting obligations for the European telecommunications sector.

In addition, it is known within the industry that some countries fail to meet basic obligations of due diligence and oversight with respect to their networks, enabling foreign entities access to SS7 and Diameter for the purposes of conducting global surveillance.

We believe that the historically limited public information about abuses has enabled the telecommunications industry to further minimize the problem. There is no public reporting from most telecommunications companies about the scale of the threats to users, the number of attacks identified and blocked, or a roadmap for addressing these threats in the future. This state of affairs will result in predictable, preventable harm to customers across the globe.

Risks in the U.S.

In April 2017, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) conducted a major study that concluded: “all U.S. carriers are vulnerable to these exploits, resulting in risks to national security, the economy, and the Federal Government’s ability to reliably execute national essential functions.” According to the DHS report, “SS7 and Diameter vulnerabilities can be exploited by criminals, terrorists, and nation-state actors/foreign intelligence organizations” and “many organizations appear to be sharing or selling expertise and services” that could be used to conduct such espionage.

In response to a 2017 letter by Senator Ron Wyden requesting information about what steps U.S. carriers were taking to secure their networks, AT&T acknowledged that “hundreds of carriers now have access to SS7, many of them in unstable or unfriendly nations where credentials can be compromised…even sold on the open market for a fee.” The company went on to acknowledge that “the trust model is no longer fully reliable.”

In a 2018 letter to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Senator Wyden revealed that an unnamed U.S. carrier had suffered a SS7-related breach of customer information, which it reported to federal authorities. Subsequent investigative reporting revealed that the FCC had ignored expert recommendations by the DHS and instead espoused a voluntary compliance program at the urging of the wireless industry. Additionally, the reporting found that, although SMS messages are vulnerable to SS7 interception, the wireless industry successfully lobbied the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to keep SMS text messages as an approved method of two factor authentication in U.S. government standards.

The troubling inability of the U.S. government and telecommunications sector to address SS7 vulnerabilities is mirrored in many countries around the world.

Risks in Canada

In 2017, a joint investigation undertaken by CBC News and Radio Canada, in cooperation with German security researchers, demonstrated an SS7 attack against a sitting member of parliament, Matthew Dubé. With only a telephone number, the investigators were able to use SS7 vulnerabilities to track Dubé’s precise movements and intercept his calls. The tests were conducted over both the Rogers and Bell networks.

In its 2018 annual report, Canada’s Privacy Commissioner noted the investigation, flagged SS7 security weaknesses, and called on the Canadian government and industry to work together to resolve them. In response, Canada’s signals intelligence agency, the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), said that “the security issues surrounding SS7, have been known for some time” and that it had been working with industry partners to resolve them. However, CSE also asserted that it “is unable to discuss further details of meetings with industry partners, and we cannot disclose the participation of individual, private telecommunications partners.”

For guidance, the CSE suggested the public visit a “mobile security” information page, now available on the newly established Canada Centre for Cyber Security website in a section on “infographics.” However, the website and accompanying infographic do not mention SS7 explicitly and provide only basic advice on mobile security practices.

Legislators: Do This Now

Governments across the globe should take action to protect their citizens and their own operations. Telecommunications regulatory bodies should conduct regular audits of national networks and mandate carriers to identify, disclose, and address vulnerabilities.

The U.K. government has shown promising leadership in addressing carrier security, with recently proposed legislation that requires carriers to secure their networks and gives Ofcom (the U.K. telecommunications regulator) the authority to ensure compliance. The newly proposed powers granted to Ofcom include the ability to conduct audits and to compel the production of records and other information related to a carrier’s security efforts. The proposed law would also, for the first time, require carriers to disclose compromises to their customers and provide for fines in some cases.

The European Union has also taken note of telecommunication network vulnerabilities and made recent recommendations that encourage EU nations to conduct regular analyses of the threat landscape, adopt minimum security standards, and require incident reporting. We also note that Nordic regulators have undertaken efforts to establish best practices for protecting their infrastructure from SS7 attacks.

In contrast, the U.S. FCC has shown no will to compel carriers to report incidents or undertake serious security improvements. Given the rapid proliferation of SS7 and Diameter exploitation technologies both to states and non-state actors, it seems likely that without urgent action, U.S. consumers and government operations will be targeted by an increasingly wide range of potential threats.

Wireless Carriers: Do This Now

We urgently recommend that telecommunication companies examine SS7 and Diameter traffic originating from providers in countries where we have identified a Circles deployment for patterns of abuse. The SS7 and Diameter exploitation marketplace, as well as the wireless threat landscape, are constantly evolving. The recommendations provided by the DHS are highly relevant: every major wireless carrier should receive an independent SS7 and Diameter audit every 12-18 months, and should address any identified vulnerabilities. The ENISA also provides a range of security recommendations for carriers.

We are aware that some providers, such as a number of U.S. companies, are experimenting with SS7 firewalls, which show promise in reducing some types of attacks. We urge providers to publicly disclose their roadmaps for addressing SS7 and Diameter vulnerabilities, and believe that information about SS7 threats should be included in telco companies’ transparency reporting going forward.

Sounding the Alarm: Recommendations for High Risk Users

Whether you are a journalist, human rights defender, or government employee, telecommunication network vulnerabilities may make it possible for adversaries to intercept your verification SMSes and compromise your accounts. If you believe you face threats because of who you are or what you do from any of the countries mentioned in this report, or even a country not listed above, we urge you to migrate away from SMS-based two factor authentication immediately for all accounts where it is possible. Directions on how to use a security key for some of your accounts are here.

In addition, for accounts on popular apps such as Signal, WhatsApp and Telegram, we urge you to immediately enable a security PIN or password for your account.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rapid7 and Censys for providing research access to their data feeds.

Bill Marczak’s work on this report was supported, in part, by the International Computer Science Institute and the Center for Long-Term Cyber Security at the University of California, Berkeley.

The authors would like to thank Jeffrey Knockel for peer review and Stephanie Tran for research assistance. Special thanks to several other reviewers who wish to remain anonymous as well as TNG.

Financial support for this research has been provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Hewlett Foundation, Open Societies Foundation, the Oak Foundation, and Sigrid Rausing Trust.

Appendix A: Circles Deployments, Continued

Australia

We identified a single Circles system in Australia. We cannot verify the identity of the operator. The system’s Check Point firewall was also reachable through an IP address in a Malaysian datacenter (EstNOC Malaysia), which appears to be forwarding traffic onwards to the Australian IPs. The Australian IPs, on Optus and TPG, geolocate to Australia’s capital Canberra, per MaxMind.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| 2018/10/30 – Present | 220.101.113.194 – 196 27.33.222.130 – 132 220.245.33.62 103.230.142.4 |

Belgium

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Dates Active | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

BMW Bagel |

| 2017/2/25 – Present | 81.246.73.98 – 100 84.199.16.226 – 228 |

Denmark

We identified a single client in Denmark, Dodge Diamondback, which appears to be the Danish Army Command (Hærkommandoen). The firewall IPs for the system are in a range of IP addresses named “BSC-HOK-NET,” and WHOIS data shows an associated phone number (+45 9710 1550) that a Google search reveals is linked with the Danish Army. We believe that “HOK” is a reference to the Danish “Army Operational Command,” which was restructured in 2014 and is now apparently known as the Danish “Army Command.”

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dodge Diamondback | Army Command (Hærkommandoen) | 2015/6/1 – 2020/4/30 | 80.63.69.243 – 245 |

Ecuador

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excalibur Cosmos | 2015/6/1 – 2019/9/17 | 181.113.61.242 – 244 | |

| 2015/6/1 – 2017/2/13 | 181.211.37.50 – 52 181.39.50.66 – 68 |

El Salvador

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evoque Lempa | 2017/2/13 – Present | 201.247.172.155 – 157 |

Estonia

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/10/30 – Present | 193.40.226.194 – 196 193.40.226.66 – 68 |

Equatorial Guinea

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013/10/30 – Present | 193.251.153.1 – 3 |

Honduras

We identified two Circles systems in Honduras. One unnamed system appears to have been operated by the National Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence (DNII), as public WHOIS information records that the firewall IPs are registered to “DNII.”

| Possible Identity | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Directorate of Investigation and Intelligence (DNII) | 2017/6/29 – Present | 181.210.19.211 – 213 | |

| Honda Thor | 2016/7/12 – Present | 190.4.27.122-124 | |

| Honda Honduras | (Circles IPs) |

Indonesia

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/9/11 – Present | 203.142.69.82 – 84 | ||

| 2018/9/4 – Present | 117.102.125.50 – 52 |

Israel

We identified a single system in Israel. However, this system was not labeled as a “client” system, and was instead labeled as a “telco” system. Additionally, the name “Lexus” does not have the first letter “I” for Israel, which is inconsistent with other client naming schemes.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telco Lexus Canola | 82.166.142.26 – 28 |

Kenya

We identified a single system in Kenya. Though MaxMind geolocates the IP addresses to Mauritius, a traceroute indicates that the IP addresses are in Kenya. The name “Kali” appears inconsistent with other client naming schemes, as we are not aware of any automotive brand named “Kali.”

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telco Kali Rainbow | 41.72.215.226 – 228 |

Malaysia

We identified one Circles system in Malaysia, named Pixcell Mazda Farmer. We cannot verify the identity of the operator. We believe Pixcell is a reference to a Circles device, whose description in United States Federal Communication Commission (FCC) and United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) documents suggests it is a portable IMSI catcher. While the Pixcell model that underwent the FCC approval process apparently starting in October 2016 has WCDMA (3G) support, a January 2017 photograph of the Pixcell model submitted to the USPTO appears to indicate that WCDMA support was removed, and support for LTE (4G) was added, based on the absence of a “WCDMA” status light, and an “LTE” status light in its place.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pixcell Mazda Farmer | 2016/9/25 – 2018/4/17 | 60.54.119.242 – 244 | |

| Mazda Sky | (Circles IPs) |

Mexico

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018/10/16 – Present | 189.240.115.18 – 20 | ||

| Mercedes Panda | 2015/6/1 – Present | 187.217.170.233 – 235 189.240.245.141 189.240.254.193 – 195 189.240.254.202 – 204 189.240.254.209 – 211 189.240.254.217 – 219 201.147.171.225 – 227 201.147.171.233 – 235 | |

| Mercedes Koala | 2015/9/12 – 2017/10/24 | 187.174.194.23 – 28 | |

| Mercedes Dathomir | (Circles IPs) | ||

| Mercedes Sirius | 2015/9/12 – 2016/8/6 | 201.157.58.162 – 164 | |

| Mercedes Camelot | 2015/6/1 – 2019/10/1 | 187.217.188.220 – 222 187.217.80.162 – 164 | |

| Mercedes Ventura | SEMAR (Mexican Navy) | 2015/6/1 – 2017/8/15 | 187.217.108.81 – 83 201.116.62.192 – 194 |

| Mercedes Nightingale | (Circles IPs) | ||

| checkpoint-a | State of Durango | 2015/6/1 – 2020/4/30 | 187.141.19.195 201.139.227.74 201.148.31.122 |

| cp.slp.mx | 2015/6/1 – 2017/12/5 | 187.141.246.178 |

Peru

We identified a single Circles system in Peru, which appears to be operated by Peru’s National Intelligence Directorate (DINI), as some of its firewall IPs were in a /27 registered to “DIRECCION NACIONAL DE INTELIGENCIA – DINI” per public Whois data. The system is named Porsche Pisco. Interestingly, DINI was reported to have a surveillance project called “Pisco” that was under development in 2015. The Associated Press reported in 2016 that one of Project Pisco’s contracts was with Israeli interception company Verint.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porsche Pisco | National Intelligence Directorate (DINI) | 2015/6/8 – 2018/2/13 | 168.121.46.82 – 83 181.177.233.20 – 22 |

Serbia

We identified a single Circles system in Serbia, which appears to be operated by Serbia’s Security Information Agency (BIA), which was also a customer of FinFisher.

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shkoda Sambu | Security Information Agency (BIA) | 2015/6/1 – 2015/7/6 | 195.178.51.242 – 243 195.178.51.252 |

Vietnam

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volvo Halogen | 2015/10/12 – Present | 113.161.106.74 – 76 |

Zimbabwe

| Client Name | Possible Identity | Seen in Scan | Firewall IPs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013/11/4 – 2014/1/6 | 196.27.103.36 – 38 | ||

| Zagato Zeus | 2015/9/12 – 2017/9/19 | 197.155.229.194 -196 | |

| Zimbabwe Telcel | 2018/3/27 – Present | 41.79.56.33 – 34 |

Unknown Countries

We found names for several other Circles systems appearing in IP ranges registered to Circles. Because these names were never recorded in IP ranges that might belong to Circles customers, we are unsure of their identity. The names were: GTR Whitehippo, Icarus Shemer, Kodik Kite, and Opel Oranit.

- Check Point is aware that its firewalls publicly produce this hostname information, and does not consider this to be a security issue, remarking that this is “public information.” ↩︎

- We found a total of 19 distinct TLS certificates ever recorded as matching this regular expression, returned by a total of 57 IP addresses. Ultimately, our search for TLS certificates containing this regular expression did not help us identify any additional Circles systems, though it did help us tie IP addresses together as belonging to the same system, based on returning the same TLS certificate. ↩︎

- Interestingly, the “War Room” incorrectly translates its Thai name (กองอำนวยการรักษาความมั่นคงภายใน) into English as “International Security Operations Command.” ↩︎

- Firewall IPs in the same /30 as smart.gov.ae registered to “Dubai Government” and same /26 as wsg.dubaipolice.net. ↩︎