Key Findings

- According to a February 2020 report in the publication Bitter Winter, police in Qinghai Province in China have conducted a program of compulsory iris scan collection targeting residents of the city Tsoshar (Haidong). Building on Bitter Winter’s work, this report finds further evidence of police-led mass iris scan collection in Qinghai, a region with a population that is 49.4% non-Han, including Tibetans and Hui Muslims. The evidence in this report includes details of iris scan collection in three regions of Qinghai, the history of the program, how police collect data, the involvement of Chinese surveillance company Super Red, and how many iris scans police have collected.

- Of the 189 publicly available sources we uncovered, 53 contained figures for the number of iris scans police had collected. Based on our analysis of these 53 reports, we estimate that between March 2019 and July 2022, police may have collected between roughly 1,248,075 and 1,452,035 iris scans, representing between one fifth (21.1%) and one quarter (25.6%) of Qinghai’s total population (5.9 million). The number of irises scanned would make mass iris scan collection in Qinghai the largest known program conducted in China relative to population, with the possible exception of an earlier program in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

- Police have given a number of justifications for mass iris scan collection, including fighting crime, finding missing people, and upgrading national ID cards. Based on our analysis, the lack of a single justification for mass iris scan collection may reflect the fact that police could use the program for multiple purposes. Iris scan collection is part of long-standing police intelligence gathering programs. Through mass iris scan collection, Qinghai’s police are effectively treating entire communities as populated by potential threats to social stability.

Background on Iris Scan Collection Globally

Biometrics is the measurement or calculation of human characteristics like fingerprints, DNA, faces, voices, and gait. These measurements and calculations can in turn be used to verify a person’s identity. One form of biometric identification is iris recognition, or the analysis of the coloured part of the eye surrounding the pupil. To identify a person’s iris, infra-red spectrum cameras are used to map more than 200 features of the iris, with this image then converted into a code that can be algorithmically read. These images can then be compared against the images of other iris scans for the purpose of identifying a person or verifying their identity.

Iris recognition tools are increasingly accurate. The presence of some ocular diseases or the wearing of contact lenses can reduce the accuracy of iris recognition tools. However, a 2018 evaluation found that the most accurate iris recognition algorithms examined had a false negative identification rate of one out of every 150 matches, and a false positive identification rate of one out of every 1,000 matches.

For this reason, border authorities, services run by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the Indian government’s biometric ID system Aadhaar have all used iris recognition as part of programs requiring the fast and accurate identification of individuals. Using handheld or surface-mounted infrared cameras, iris patterns can be scanned and then digitized and stored. These scans can be used to verify a person’s identity by matching iris scans against previously captured images, or to identify a person by comparing their irises against a larger database of other people’s scans. How useful iris scans are in identifying people is dependent on the number of iris scans already recorded. The greater the number of individual iris scans in a database, the greater the likelihood that iris recognition technologies can positively identify someone based on an iris scan.

Among the most enthusiastic adopters of these technologies are militaries and police forces. Some of the most well documented cases come from the United States. The US military operating overseas has used biometric recognition tools to identify local national hires since Kosovo in 2001. As part of the war in Afghanistan, the US military collected iris scans and other biometric markers from millions of Afghans, while during the occupation in Iraq the US military collected iris scans for the purpose of screening people entering or leaving particular areas. In both cases, iris scans were collected using mobile iris recognition devices as part of broader counter-insurgency operations.

In the 2010s, domestic law enforcement in the United States began adopting these technologies. In 2013, the FBI began a pilot program to work with local police departments to collect and store iris scans from arrestees. By 2020, the database – part of the FBI’s Next Generation Identification biometric data system – reportedly contained 1.8 million iris scans.

Civil society groups, constitutional rights experts, and researchers have raised privacy concerns about the increasing use of iris recognition technologies, including how iris scans are stored, who has access to them and for what purposes, and how secure iris databases are from unauthorized access. In 2017, sheriffs in counties along the United States-Mexico border voted to participate in a trial of tools used to scan, collect, and analyze irises in order to identify migrants, leading the American Civil Liberties Union to warn that these tools could encourage racial profiling or erode the privacy rights of those subjected to iris scan collection by the police. The potential ability to scan irises at a distance has also led researchers and US constitutional rights experts to warn that police could use iris recognition devices on people unaware police are monitoring them.

Other concerns have focused on data security and privacy. With the end of military conflict, biometric data collected by one military may end up in the hands of another. Following the withdrawal of the US military from Afghanistan in 2021, reports emerged of the Taliban’s potential capture of US military biometric devices containing iris scans, fingerprints, and other identifying information on Afghans who had worked with coalition forces.

Background on Iris Scan Collection in China

In China, iris scan collection dates back at least to the mid-2010s. Some of the earliest iris scan programs focused on the problem of missing children. In 2016, iris recognition technology company EyeSmart (释码大华) proposed the building of 100 stations across Wuhan, Hubei to collect iris scans from children. The following year in November 2017, the Chinese government launched a national children’s iris database containing 40,000 iris scans. By September 2018, authorities were were working with another company IrisKing (中科虹霸) to set up 400 collection stations across China. Participation in these or similar database projects appears to be voluntary, with some schools charging parents of kindergarten students a fee for storing iris scans from their children.

China’s Ministry of Public Security is also interested in iris recognition technologies. Chinese researchers writing in 2021 in Forensic Science and Technology note that, compared with other biometric identifiers like DNA or facial scans, iris scans are a more stable, reliable, and fast way for the police to accurately identify a person.

In 2016, the Beijing Public Security Bureau began building an iris scan database focused on target people. However, one of the earliest known programs of police-led mass iris scan collection in China dates back to at least 2017 in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. As part of a wider campaign of state repression against Uyghurs and others in Xinjiang, police collected biometric data from residents of the region, including iris scans, DNA samples, fingerprints, and facial scans. It is not clear how many iris scans police collected in Xinjiang. In 2017, police in the regional capital Urumqi began building a local iris identity information database (虹膜身份信息数据库), which by January 2018 reportedly contained iris scans of 300,000 people, or roughly 13% of the city’s then-population of 2.2 million. Other reports indicate that coverage could have included everyone aged 12 to 65 years of age in areas targeted by police for data collection.

Outside Xinjiang, police in other areas of China have also conducted iris scan collection programs. Police in Zhengzhou, Henan introduced a program in 2018 to scan the irises of people applying for e-bike drivers licenses, while in 2022 anti-narcotics police in Jinzhong, Shanxi began collecting iris scans and other biometric data like DNA samples and voice samples from registered users of drugs. Yet as late as 2018, China’s Ministry of Public Security did not have a unified national platform for collecting and storing iris scans, according to an article in the Journal of People’s Public Security University of China (Science and Technology).

It was not until 2019 that the Ministry of Public Security began exploring a national program of iris scan collection. Unlike earlier iris scan collection efforts, this program extended beyond any one region of China and or any particular group of Chinese citizens. In April 2019, the Ministry of Public Security released the “Notice on Implementing Iris Information Collection and Application Work” (关于开展虹膜信息采集应用工作的通知). Academic writing and industry publications, however, suggest that the Notice called on Public Security Bureaus across China to support the application of the Ministry of Public Security’s “iris system” (部级虹膜系统) and that provincial-level Criminal Investigation Branches should begin building “province-level iris systems” (省级虹膜系统).

While an original copy of the Notice is not available, another national-level document is: the “Construction Plan for National Criminal Investigation Information Specialized Application System’s Iris Identity Inspection Subsystem” (全国刑侦信息专业应用系统虹膜身份核查子系统建设方案). Released by the Ministry of Public Security in February 2019, the Construction Plan calls for strengthening iris scan database construction for the purpose of “attacking crime and social management and control” (打击犯罪和社会管控) and clarifies the roles that national, provincial, municipal, and county-level public security organs have in constructing the database system.

The Construction Plan also specifies from whom iris scans are to be collected: “target people, crackdown targets, and people who have broken the law” (重点人员、打击处理人员和违法犯罪人员) and “target people from Xinjiang” (新疆重点人员). “Target people” are Chinese citizens who police view as threatening social stability, like users of drugs, practitioners of banned faiths, petitioners, and people with mental health issues. “Crackdown targets” may refer to targets of police campaigns against particular categories of offenses, like gambling or telemarketing fraud. “People who have broken the law” refers to people accused of both criminal offenses like sexual assault and non-criminal administrative offenses like using drugs. “Target people from Xinjiang” includes Uyghurs and others from Xinjiang accused of fomenting separatism, terrorism, or extremism, or otherwise seen by police as threatening social stability.

According to the Construction Plan, public security organs at all administrative levels are to set up “leading small groups” (领导小组) to direct the construction and operation of a national iris identity inspection subsystems according to a specific timeline. By the end of March 2019, a national ministry-level iris database containing scans from Xinjiang target people was to be completed. By the end of April, checkpoints surrounding Beijing and other target areas (重点区) were to install iris recognition equipment connected to the ministry-level database to scan for target people from Xinjiang and “suspicious people” (可疑人员) in order to support a secure celebration of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic.

By the end of August, police across China were to establish provincial and local-level iris scan databases. Police were to verify the identities of and collect iris scans from target people, crackdown targets, and criminal offenders. And by the end of 2019, personal information and iris scans from these groups was to be added to national and provincial-level information resource service platforms (信息资源服务平台) to facilitate iris scan comparisons between national and provincial databases and “provide effective and mutually shared iris comparison services for all branches of the police” (为各警种提供高效、共享的虹膜比对服务).

The Construction Plan makes clear that the Iris Identity Inspection Subsystem is also connected to other “public security data resource system” (公安数据资源体系) and “big data centres at the national, provincial, and municipal level” (部省市三级大数据中心). Public security data resource systems are used by the Ministry of Public Security for a variety of purposes, including population management. Big data centres refers to a project begun in 2020 and spearheaded by the National Development and Reform Commission to build 10 computing centres across China to promote digital innovation, economic development, the use of green energy, and to transfer data from eastern to western regions for the processing and storage.

It is not clear if the Ministry of Public Security or Public Security Bureaus across China were able to stick to the timeline laid out in the Construction Plan. However, since the release of the Construction Plan, police in places like Hubei Province have attempted to implement the tasks laid out in the Plan.

There are also indications that municipal public security bureaus have invested in building iris databases large enough to cover entire local populations. In 2019 the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau and IrisKing announced the building of a database capable of containing up to 20 million iris scans, roughly equivalent to the city’s population of 21.89 million, “to facilitate public security management” and “as [a] crime-fighting tool.” According to the 2021 article in Forensic Science and Technology, the capital of Henan, Zhengzhou, has an iris scan database capable of storing 10 million scans, nearly equal to the city’s population of 10.52 million. However, there are no public reports indicating that either the Beijing or the Zhengzhou databases have been operationalized or actually contain iris scans from every permanent resident of the two cities.

Background on Iris Scan Collection in Qinghai

Since the release of the “Notice on Implementing Iris Information Collection and Application Work” and the “Construction Plan for National Criminal Investigation Information Specialized Application System’s Iris Identity Inspection Subsystem” in 2019, reports of police across China building large-scale iris scan databases have emerged. Among these reports is one published in February 2020 by Bitter Winter, which details a program of mass iris scan collection by the Public Security Bureau of Qinghai Province (pop. 5.9 million).

According to Bitter Winter, police collected iris scans at police stations and at the homes of residents of Tsoshar (Haidong) (pop. 1.35 million), warning that refusal to cooperate would make it “difficult for them in the future to buy tickets for traveling and even withdraw money.” Bitter Winter’s report also noted the collection of iris scans from children in the provincial capital Xining, ostensibly aimed at addressing the problem of missing or trafficked children. According to reports from Chinese media, some locals expressed concern about the security of the data their children were providing authorities, as well as a 200 RMB fee for inclusion in the database. Later reports clarified that participation was voluntary, suggesting that this program was distinct from the police-led program of mass iris scan collection described by Bitter Winter.

Bitter Winter’s report is not the first publicly available report documenting mass iris scan collection in Qinghai. In 2010, Chinese media reported that in Yulshul (Yushu) the Provincial Department of Science and Technology and the Chinese Academy of Sciences partnered to implement a trial program to collect iris scans from 3,598 herders in the wake of the April 2020 Yulshul earthquake.

However, Bitter Winter’s report is the first to discuss police engaging in mass iris scan collection outside any ongoing criminal investigation. Bitter Winter’s report is also part of a well-documented record of state surveillance and repression in Qinghai. Much of this surveillance and repression has focused on the province’s Tibetans and other non-Han people who make up 49.4% of the province’s population. Tibetans have been detained and prosecuted for political activism, and Tibetan monks have immolated themselves in protest against party-state rule.

Police have also used anti-crime measures to arrest and jail Tibetan activists. A nationwide “sweep the black” campaign against organized crime between 2018-2021 have been used since 2018 in Tibetan areas of Qinghai to punish people protesting corruption, demanding compensation for property damage by state developers, or complaining about land expropriation by local governments.

Controls in Qinghai have also extended to land usage and population resettlement. In Yulshul in 2021, local authorities rescinded the right of Tibetan nomads to use grasslands for raising livestock and community settlement, a right authorities originally granted to nomads for up to 50 years beginning in 1985. Authorities justified mass population resettlement in Qinghai, which dates back to the early 2000s, in terms of ecological protection and raising living standards. However, critics have claimed that the designation of former grazing areas as protected areas will further cultural loss among nomads and that population resettlement in areas of Qinghai, Tibet, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia are a form of population control.

Language rights are also under threat in Qinghai, where since the mid-2010s authorities have promoted Mandarin Chinese as the primary language of instruction at schools in Tibetan areas. Authorities have closed Tibetan language schools and police have detained people who have criticized state language policies.

In addition to controls on Tibetans and Tibetan Buddhists, authorities in the provincial capital Xining have also “sinicized” Hui Muslim mosques through the removal of minarets and domes, as part of nationwide efforts to sinicize Islamic practices. Other religious minorities have also been targeted for repression, including the decision of police in 2012 to detain 400 members of the banned spiritual movement Church of Almighty God.

Mass iris scan collection in Tsoshar, as reported by Bitter Winter, appears to be one part of much larger and long-standing instances of state repression and surveillance in Qinghai. Yet while Bitter Winter was the first English language publication to discuss mass iris scan collection in Qinghai, the report left a number of questions unanswered, including whether iris scan collection was confined to Tsoshar, how long the program had been in operation, the specific measures police used to collect data, what companies have sold iris scan collection or iris recognition equipment to the police, or how many iris scans police had collected.

Understanding Qinghai’s iris scan collection program requires answering these questions. What’s more, an accurate assessment of police iris scan collection in Qinghai can provide insight into police biometric surveillance across China, and the legality of mass biometric surveillance under the country’s legal system. By analyzing publicly available sources from Qinghai, and examining these sources in light of existing research on policing and biometric surveillance in China, our report builds on Bitter Winter’s work to detail the scope and character of mass iris scan collection in Qinghai.

Methodology

To explore the character and scale of the police-led mass iris scan collection program in Qinghai, we searched online for publicly available reports concerning this campaign. Data collection for this report began January 8, 2022 and ended September 26, 2022.

All sources were publicly available and found online through Chinese language keyword searches on the social media platform WeChat and on the search engines Google and Baidu. In total, we used 7 keywords arranged into 6 combinations (Table 1).

| Keywords (Chinese) | Keywords (English) |

|---|---|

| 采集 + 虹膜 | Collection + iris |

| 青海 + 虹膜 | Qinghai + iris |

| 公安 + 虹膜 | Public security + iris |

| 派出所 + 虹膜 | Police station + iris |

| 信息 + 虹膜 | Information + iris |

| 数据 + 虹膜 | Data + iris |

Table 1: Keywords

When identifying which sources to collect, we only selected those sources which referred to police iris scan collection, iris database construction, or the importance of iris scan collection as a feature of police work in Qinghai. To ensure greater trustworthiness, we only collected sources from official government or public security WeChat accounts, official government or public security social media accounts published through the news website The Paper, or Chinese domestic news websites. In total, we collected and collated 189 sources (Table 2).

| Source | Number of Reports |

|---|---|

| The Paper | 111 |

| 77 | |

| News Websites | 2 |

| TOTAL | 189 |

Table 2: Primary Sources by Origin

Sources were saved as PDFs and archived using Archive Today, then collated in a spreadsheet according to date and location for further analysis.

We also took steps to ensure that sources referred specifically to mass police-led iris scan collection, rather than other instances of iris scan collection. For example, reports of a voluntary iris scan collection program in Xining focused on preventing elderly people from going missing were not collected or analyzed. Similar programs occur elsewhere in China and cannot be definitively linked to police-led mass iris scan collection in Qinghai.

To contextualize mass iris scan collection in Qinghai, we also drew on other publicly available sources. These sources included government websites which discussed public security programs and police data collection efforts, and Chinese academic literature on police information and iris scan database systems.

There are limits to the 189 sources we collected. These sources alone do not provide a fully comprehensive account of police-led mass iris scan collection in Qinghai. Nor was any single document found which articulates the purpose and scope of mass iris scan collection in Qinghai. However, by collecting 189 publicly available sources discussing mass iris scan collection in Qinghai, we were able to create a composite (albeit incomplete) picture of this program.

Findings

The 189 sources we collected provide insight into the scope of police-led mass iris scan collection in Qinghai and expand upon Bitter Winter’s February 2020 report. Through examination of the 189 sources we collected, we were able to: identify the timeline and geographical scope of police-led mass iris scan collection in Qinghai; the measures police used to collect iris scans; the name of one company involved in the program; and the number of people from whom police collected iris scans. Our research indicates that the Qinghai Public Security Bureau’s mass iris scan collection program is part of broader domestic intelligence gathering programs which target men, women, and children outside any ongoing criminal investigation.

Implementation of the mass iris collection program in Qinghai began March 2019 and continued as late as July 2022 (Table 3).

| Year | Number of Reports |

|---|---|

| 2019 | 62 |

| 2020 | 101 |

| 2021 | 19 |

| 2022 (to July) | 8 |

| TOTAL | 189 |

Table 3: Primary Sources by Year

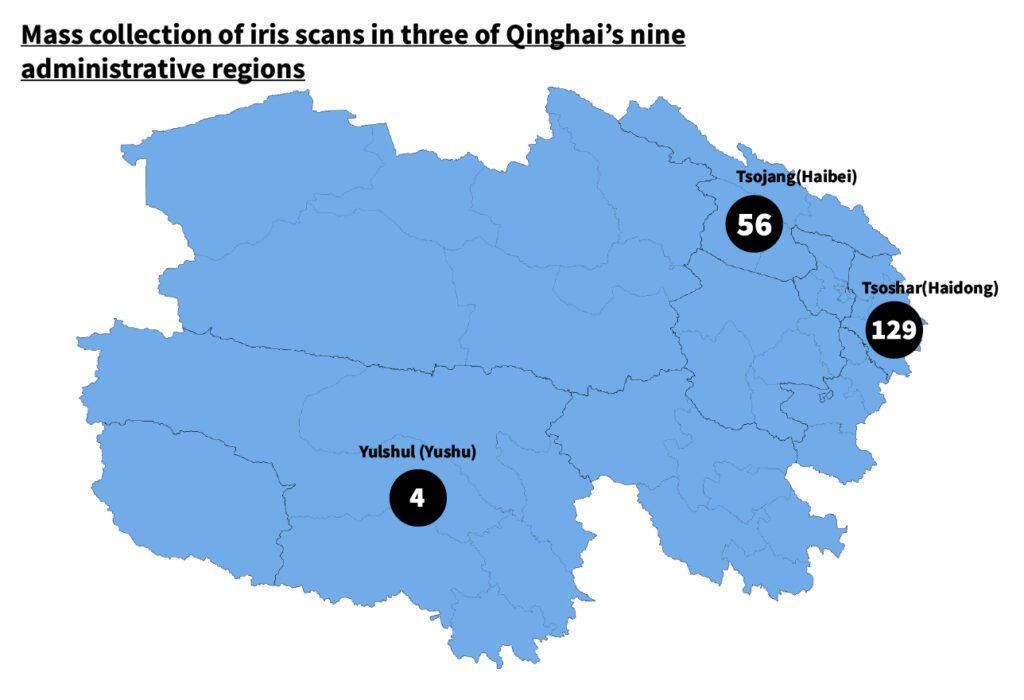

These 189 sources referred to police-led mass collection of iris scans in three of Qinghai’s nine administrative regions (Table 4). These sources do not refer to iris scan collection in the remaining six administrative regions of Qinghai.

| Location | Number of Reports |

| Tsoshar (Haidong) | 129 |

| Tsojang (Haibei) | 56 |

| Yulshul (Yushu) | 4 |

| TOTAL | 189 |

Table 4: Primary Sources by Location

Mass iris scan collection in Qinghai does not appear to be connected to any ongoing criminal investigation. In keeping with the Ministry of Public Security’s 2019 Iris Identity Inspection Subsystem Construction Plan, mass iris scan collection in Qinghai appears to be part of larger police-led data collection programs aimed at strengthening police surveillance capabilities.

A report on a March 2019 public security meeting in Tsoshar, conducted at the start of Qinghai’s mass iris scan collection program, gives insight into the role of iris recognition technologies in policing. The report describes an increasingly precarious domestic security situation necessitating new forms of biometric surveillance:

“Accompanying rapid economic and technological development have been an increasing number of domestic terrorism, public security, and criminal cases. Criminals use cosmetic surgery, forgery, and false documents to hide their identities, seriously threatening national stability and people’s lives and property. Traditional ways of verifying identity, like ID cards and passports, are facing a crisis. Although biometric recognition technologies used to assess fingerprints, voice prints, faces, and DNA play important roles in their respective fields, they cannot accurately determine a person’s true identity in mere seconds.”

According to this report, iris recognition technologies are possible solutions to these problems:

“Iris recognition is currently the fastest and most accurate biometric recognition technology, and benefits from uniqueness, stability, and non-contact recognition, and can connect personal identity documents with iris biometrics. By describing, matching, and classifying the human eyes’ iris through pattern recognition, image processing, and other methods, automatic personal identity authentication can be achieved. Rapid iris identification can accurately determine the true identity of a person and issue a timely alarm for a suspicious person, effectively solving problems caused by forgery, false documents, and cosmetic surgery.”

Who qualifies as a “suspicious person” is not specified. The 189 sources we examined, however, do not suggest that mass iris scan collection is focused on people that the police view as threats to social stability, such as the target people mentioned in the 2019 Construction Plan.

Instead, Qinghai’s police have targeted entire communities for mass iris scan collection. An April 2019 news report from Tsoshar states that police planned to collect iris scans from all long-term residents, people involved in legal cases or civil disputes, passport applicants, and migrant workers. A later report from April 2020 from Haiyan County in Tsojang referred to police collection of iris scans from both permanent residents and migrants. By expanding iris scan collection to all long-term and migrant residents, police in Qinghai are treating entire communities as potential threats to social stability.

Planning for iris scan collection in Qinghai dates back at least to November 2018 in Tsoshar, prior to the release of the February 2019 Construction Plan. Beginning in March 2019, police across Tsoshar began receiving training in how to use iris scanners and organizing iris scan collection efforts.

Small groups of police officers were responsible for collecting data from local homes. In some cases, police adopted a “police + village police + volunteer method” (民警+村警+志愿者模式) of collecting iris scans, though who volunteers were is left unstated. In other cases, police, auxiliary police, and village police participated in iris scan collection.

Early reports indicate that police focused on areas with high concentrations of people like public squares and schools. In Huzhu Tu Autonomous County in Tsoshar, police collected iris scans from people at work units, schools, and commercial enterprises, while in Gangcha County in Tsojang, police collected iris scans at village committees, work units, temples, and construction and from migrant workers at construction sites. In these well-trafficked public areas, police routinely used desk-mounted iris scanners or operated iris scan machines out of police cars.

Iris scan collection could be combined with other police work, such as surveillance of target people or conducting urine drug tests of registered users of drugs. In other cases, public security meetings discussed iris scan collection alongside local implementation of a nationwide surveillance camera program translated alternately as “Dazzling Snow” or “Sharp Eyes” (雪亮工程). Iris scan collection was part of stability maintenance work in the lead up to the May 1 holiday. And in Tsojang, police collected iris scans alongside the confiscation of fake 100 yuan bills and illegal firearms.

Police also integrated iris scan collection into the broader program of “1 million police entering 10 million homes” (百万警进千万家), a national program of police-led home and business inspections and data collection that was also associated with mass DNA collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region. During home visits as part of the “1 million officers entering 10 million homes” program, police would “chew the fat” (拉家常) with locals about their lives and problems while also collecting iris scans.

Iris scan collection seems to have slowed over the last two years. From 2021 to July 2022, this report found only 27 reports of mass iris scan collection: 15 from Tsojang and 12 from Tsoshar. The drop in the number of reports may indicate that police in Tsoshar, Tsojang, and Yulshul had largely completed iris scan collection by late 2020. However, police surveillance programs piloted in one region can grow, as happened with a male DNA collection project first implemented in Henan in 2014-2016 that later expanded nationwide in 2017. It is possible that police in the future may conduct mass iris scan collection in other regions beyond Qinghai.

Company Involvement: Super Red

Mass iris scan collection in Qinghai is led by municipal Public Security Bureaus. In addition to the police, public records also reveal that at least one company, Super Red (北京万里红科技有限公司), is involved in this biometric surveillance program.

In November 2018, Tsoshar’s Public Security Bureau decided on the model of iris scan collection devices and by the following March had spent 5.21 million RMB on an iris identification system and iris database. At least a portion of the equipment was provided by Super Red, a company in which the Chinese Academy of Sciences holds a majority share. According to the company’s website, Super Red’s iris identification inspection system can associate iris scans with an individual’s ID card or passport, and can be used to identify target people and issue an alert in order to take “preemptive control measures” (提前处置进行部控,防止危险的发生).

In March 2019, technicians from Super Red installed iris scan recognition and inspection systems (虹膜采集识别核查系统) in 19 municipal public security divisions in Tsoshar. At police meetings, technicians from Super Red provided training not only for the iris recognition system, but also the company’s computer secrets technology prevention system (计算机保密技术防范系统), both of which were associated with improving public security organs’ anti-terror and population management capacities.

Super Red’s involvement in biometric surveillance extends beyond Qinghai. In 2019, Super Red reportedly finished building a national-level iris database and more than 20 provincial-level iris databases, as well as connecting provincial-level databases with the national-level database. That same year, Super Red finished building China’s largest iris database, which some reports describe as a national target population iris database (国家重点人口虹膜库).

Details on Super Red’s involvement in these iris database projects outside Qinghai are not publicly available. However, we do know that for years the Ministry of Public Security has partnered with numerous Chinese firms to develop police-run iris recognition systems. In April 2019, the Ministry of Public Security convened the National New Criminal Technology and Equipment Promotional Fair (全国刑事技术新技术新装备推广会) in Zhuhai, Guangdong, a platform attended by officers in the national and provincial Criminal Investigation Bureaus and more than 20 select technology enterprises to discuss police application of iris and vocal print recognition systems. Police interest in biometric technologies has also played a role in the growth of China’s iris recognition market from 2.17 billion RMB in 2017 to 4.8 billion RMB in 2020.

Government Justifications for Iris Scan Collection

As part of the iris scan collection program, police in Qinghai have “increased propaganda efforts” (加大宣传力度) and “won the cooperation and support of local masses” (赢得了辖区群众的配合和支持). However, public outreach has not included a clear justification for mass iris scan collection.

Police requests for cooperation have been made both through public notices and WeChat posts. In some cases, police have highlighted the role of iris scans as a crime fighting tool. In Xunhua Salazu Autonomous County in Tsoshar, iris collection was described was a way to “promote informatization construction” (推进信息化建设), a term referring to the Chinese government’s use of information technologies to collect, store, and use data. Similar justifications were found elsewhere like in Minhe Hui and Tu Autonomous County, where iris scan collection was tied to catching criminals and ensuring social stability. In Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, iris scan collection was tied to improving public security information and counter-terrorism.

Some public messaging about the program does not even mention crime or social instability. Public notices from Xunhau Salaz Autonomos County and Hualong Hui Autonomous County discussed iris scan recognition systems helping people identify themselves when boarding mass transit, setting up bank cards or passports, or passing security checks. Other notices stated that iris scans will be used to upgrade national ID cards or find missing children. And in Tsoshar’s Ledu District, iris scan collection terminals at household registration offices were described as a way to improve public security informatization, stability maintenance work, and provide convenient, fast, and effective service to the public.

Police have justified other biometric surveillance programs, like mass DNA collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region, in similarly broad terms. It’s possible that the lack of a single justification for mass iris scan collection in Qinghai may reflect the fact that an iris scan database could, in fact, be put to multiple uses. Police could use iris recognition technologies and iris scan databases to identify missing people or people with criminal records. Or these programs could be used to tighten state surveillance over ethnic minorities already subject to intense state repression, as has been the case in Xinjiang.

And while police have reportedly asked for public cooperation with iris scan collection, there is no evidence to suggest that people have the right to not cooperate. During other mass biometric data collection programs in China, police have threatened that people who refused data requests would be denied the right to travel or visit a hospital. It is possible that police in Qinghai have also used threats or intimidation to compel some locals to submit to having their irises scanned.

Connection to Mass DNA Collection

Iris scan collection is not the only police-led biometric data collection program in Qinghai. As reported by Human Rights Watch, police in some areas of the province have also engaged in mass DNA collection. However, mass DNA collection in Qinghai appears to occur independent of iris scan collection. Out of the 189 sources we examined for this report, only 11 referred to police collecting DNA, all of which came from Tsojang.

Unlike mass DNA collection in neighbouring Tibet Autonomous Region, which targeted women and men, police in Tsojang did not seem to collect DNA from women. However, two reports referring to or depicting male DNA collection in Tsojang also included photographs of police collecting iris scans from women. This suggests that even in those areas where male DNA collection occurred, police iris scan collection continued to focus on both men and women.

We therefore conclude that police are conducting a mass iris scan collection program in Qinghai independent of both mass DNA collection in Tibet and the national program of male DNA collection. However, the purpose of all three of these programs is broadly similar: to expand police surveillance over wider segments of the Chinese public.

Estimating the Scale of Iris Scan Collection

Our analysis shows that mass iris collection has occurred in at least three of Qinghai’s administrative regions: Tsoshar, Tsojang, and Yulshul. In order to estimate the scale of iris scan collection in these areas, we examined the 189 sources listed in Table 2. Out of these sources, 53 provided specific figures for the number of DNA samples police collected in two of these regions: Tsoshar and Tsojang. These figures ran from as low as 20 iris scans to as many as 130,461.

The clearest picture of the scale of mass iris scan collection comes from Tsoshar. A November 2019 post from Hualong Hui Autonomous County notes that the county’s total population of 306,824 included 150,000 people living in the county and 150,000 living or working outside Hualong. For those living within Hualong, police aimed to collect iris scans from everyone (采集量必须达到100%). For those not currently living in Hualong, police were to innovate new working methods and adopt various measures to increase data collection (要创新工作方式方法,采取多种措施提高信息采集量). A subsequent report from March 2020 states that police in Hualong had collected 130,805 iris scans, equivalent to 87% of the county’s 150,000 long-term residents.

Hualong is not the only area of Tsoshar from which we have data collection figures. In Tsoshar’s Minhe Hui and Tu Autonomous County, police had collected 308,000 iris scans by December 2019, or 70% of their intended total. This suggests that police aimed to collect scans from around 440,000 people, slightly more than Minhe’s total population of 430,000.

These reports from Hualong and Minhe suggest that police in different regions of Tsoshar attempted to collect iris scans from a majority of local residents, and in some cases entire local populations. The scale of iris collection in Tsoshar is captured in a March 2022 report which states that police had collected 1.04 million iris scans across the city. Given Tsoshar’s long-term resident population of 1.35 million, this indicates police had collected iris scans from 77% of the city’s residents.

From Tsojang, only incomplete totals from three of the city’s four administrative regions are available. By April 2020, police in Haiyan County states had collected iris scans from 10,995 people, or roughly 30.5% of the county’s population of 36,000. In Menyuan Hui Autonomous County, a June 2020 report states that police had collected 50,000 iris scans, or roughly 32% of the county’s total population of 155,800. And in March 2021, it was reported that police in Qilian County had collected iris scans from 11,505 people, or roughly 23% of the county’s population of 50,000. If we assume that these three figures reflect the final collection figures for each of these regions, we can then estimate the scale of iris scan collection in Tsojang. Adding these three figures together gives us a total of 72,500 iris scans, equivalent to 27.3% of Tsojang’s total population of 265,000 (Tsojang Estimate One in Table 4).

In addition to Haiyan, Menyuan, and Qilian, there is a fourth administrative region in Tsojang, Gangcha County. We have found multiple reports of iris scan collection in Gangcha, including one which states that police at a single police station collected 1,700 iris scans from locals. Assuming that the proportion of iris scans relative to population in Gangcha were similar to those of Tsojang’s other three counties, this would suggest that police in Gangcha collected iris scans from 27.3% of the county’s population of 45,000, or 12,285 people. This in turn would suggest that police in Tsojang have collected roughly 84,785 iris scans, representing 31.9% of Tsojang’s total population (Tsojang Estimate Two in Table 5).

| Total Number of Iris Scans as % of Local Population in Tsojang | Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Tsojang | |

|---|---|---|

| Tsojang Estimate One | 27.3% | 72,500 |

| Tsojang Estimate Two | 31.9% | 84,785 |

Table 5: Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Tsojang

The final area of Qinghai where police are known to have collected iris scans is Yulshul (population 425,000). Our report only found four reports of iris scan collection in Yulshul, none of which included precise figures. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the scale of police data collection in Yulshul. If iris scan collection in Yulshul has been as extensive as in Tsojang, then police have collected iris scans from 27.3% of the local population, or 116,025 people (Yulshul Estimate One in Table 6).1 If iris scan collection in Yulshul instead matched the scope of collection in Tsoshar, then police would have collected iris scans from 77% of local residents, or 327,250 people (Yulshul Estimate Two in Table 6).

| Total Number of Iris Scans as % of Local Population in Yulshul | Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Yulshul | |

|---|---|---|

| Yulshul Estimate One | 27.3% | 116,0252 |

| Yulshul Estimate Two | 77.0% | 327,250 |

Table 6: Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Yulshul

Based on our estimates of data collection in Tsoshar, Tsojang, and Yulshul, we were able to calculate two estimates for the scale of iris scan collection in Qinghai. To arrive at a low estimate, we only considered the known totals of iris scan collection in Tsoshar (1.04 million iris scans), the lowest estimate for iris scan collection in Tsojang (72,500 iris scans, Tsojang Estimate One in Table 4), and the lowest estimate for iris scan collection in Yulshul (116,025 iris scans, Yulshul Estimate One in Table 5).3 This gave us a combined estimate of 1,248,075 iris scans, representing 21.1% of Qinghai’s total population (Qinghai Estimate One in Table 6).

To arrive at the highest estimate, we added the known total of iris scan collection in Tsoshar (1.04 million iris scans) to the highest estimate for iris scan collection in Tsojang (84,785 iris scans, Tsojang Estimate Two in Table 4), and the highest estimate for iris scan collection in Yulshul (327,250 iris scans, Yulshul Estimate Two in Table 5). This gave us a combined estimate of 1,452,035 iris scans, representing 24.6% of Qinghai’s total population (Qinghai Estimate Two in Table 7).

| Total Number of Iris Scans as % of Qinghai’s Population | Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Qinghai | |

|---|---|---|

| Qinghai Estimate One | 21.1% | 1,248,075 |

| Qinghai Estimate Two | 25.6% | 1,452,035 |

Table 7: Estimated Total Number of Iris Scans Collected in Qinghai

If we are correct in concluding that police have collected iris scans from roughly one fifth to one quarter of Qinghai’s population, then mass iris scan collection campaign in Qinghai is the largest known campaign (relative to population) conducted anywhere in China, with the possible exception of Xinjiang.

Legal Framework on Data Privacy in China

China has laws and regulations which cover how biometric or personal data can be collected and stored, by whom, and for what purpose. However, these laws and regulations have not constrained the Qinghai police’s program of mass iris scan collection.

According to Article 2 of the Police Law, China’s police are responsible for maintaining national security and social order, and preventing and punishing illegal activity. In line with these responsibilities, police have the right to collect biometric data under certain conditions. Article 132 of China’s Criminal Procedure Law states that police may collect “biological samples” (生物样本) from victims or suspects in criminal proceedings, while Article 50 of the Anti-Terrorism Law states that public security organs can collect iris scans when investigating suspected terrorist activity. Article 3 of the Resident Identity Card Law states that citizens obtaining resident identity cards must register their “fingerprint information” (指纹信息).

Police collection of iris scans in Qinghai takes place outside the scope of the Criminal Procedure Law and the Anti-Terrorism Law. Those targeted by police are not criminal suspects, victims, or suspected terrorists. And despite references to the use of iris scan collection to help upgrade national ID cards, the Resident Identity Card Law specifies that the only biometric data identity card applicants need to register is their fingerprints. And because mass iris scan collection lacks a legal basis, it is also arguably in conflict with Article 37 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, which prohibits “[u]nlawful detention or deprivation or restriction of citizens’ freedom” and “unlawful search of the person of citizens.”

Public security officials have in the past publicly expressed awareness of the legal limits on their authority to collect biometric data, specifically from children. In a 2016 article in China Daily, the then-head of the Ministry of Public Security’s Office of Combatting Against Human Trafficking Chen Jianfeng stated that “[b]iometric data, such as DNA or iris scans, are people’s private information and by law, the police have no right to forcefully collect children’s biometric data.” Yet as our analysis demonstrates, police in Qinghai have forcefully collected biometric data from children, as they have in mass DNA collection campaigns in the Tibet Autonomous Region and across China.

Legal concerns about compulsory biometric data collection by police are not unique to Qinghai. Police outside the province have conducted other mass biometric data collection programs – notably mass DNA collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region and a national program of mass male DNA collection – in ways that find no basis in the Criminal Procedure Law or the Anti-Terrorism Law. Despite the limits on the collection of genetic data stated under the 2019 Regulations on Human Genetic Resources Management and the draft 2022 Detailed Rules for the Implementation of the Regulations on the Management of Human Genetic Resources, police across China have collected DNA samples from millions of people outside of any criminal investigation.

Chinese legal scholars have highlighted the risks to privacy and personal liberty posed by state biometric data collection. In a 2019 online essay, Lao Dongyang, a professor of law at Tsinghua University, warned that state and private biometric surveillance programs in China have challenged the presumption that people are innocent until proven guilty: “[T]he current security measures, no matter how you look at them, are based on the presumption of guilt. Everyone is presumed to be a danger to public safety and all are required, without exception, to pass through increasingly stringent security checks.”

In this same essay, Lao further argued that state biometric data collection programs needed “explicit legal authorization” in order to operate. “Without the authorization, they cannot do it; the government has no right to collect the biometric data of ordinary citizens in the name of security.”

Biometric data collection by private actors has also elicited pushback from legal scholars. In 2019, Guo Bing, a professor of law at Zhejiang Science and Technology University, sued a zoo in Hangzhou for violating China’s Consumer Protection Law by demanding that all visitors submit to facial recognition registration in order to enter the zoo. Under Article 29 of the Consumer Protection Law, operators can only collect and use personal data in ways that are necessary, legitimate, and legal, and with the consent of the consumer. The following year in 2020, a court in Hangzhou ruled in favour of Guo and ordered that the zoo delete any facial recognition data it had collected from him, a decision which was upheld in 2021 on appeal. However, the Consumer Protection Law does not impose limits on the power of China’s police to collect biometric data from Chinese citizens.

Discussion

Since March 2019, police in Qinghai Province have conducted a program of mass iris scan collection. Based on our analysis of 189 publicly available sources, we believe that between March 2019 and July 2022 police in three regions of Qinghai – Tsoshar, Tsojang, and Yulshul – collected iris scans from a total of between 1.2 million and 1.4 million people, or between one fifth and one quarter of Qinghai’s total population. These people do not appear to be accused of any criminal offense nor victims of any crime. Instead, police have effectively treated entire communities as potential threats to social stability.

Police surveillance programs – including networks of informants and the “grid management” of urban neighbourhoods – are not unique to the Xi administration, nor is police collection of biometric data from criminal suspects. What is unique to the Xi era is police-led mass biometric surveillance of entire populations. Alongside the Xi administration’s concern with achieving “comprehensive national security” (总体国家安全), police across China have launched coordinated biometric data collection programs. These programs have collected millions of DNA samples in the Tibet Autonomous Region and Xinjiang, as well as from men across China.

In Qinghai, police biometric surveillance has focused on iris scans. Like other mass biometric data collection programs in China, police collection of iris scans in Qinghai has occurred outside any ongoing criminal investigation. Qinghai’s police have targeted everyone from elementary school students to the elderly. And like mass DNA collection in the Tibet Autonomous Region and Xinjiang, many of those police have targeted are ethnic minorities, including Tibetans and Hui Muslims.

By collecting iris scans from entire communities, and associating these images with personal files, police in Qinghai possess a powerful tool of biometric surveillance. What purpose this tool will play is unclear. Sources examined for this report indicate that police have provided the public with vague justifications for iris scan collection, including fighting crime, finding missing people, and upgrading national ID cards.

This lack of clarity may reflect the lack of a singular motivation for the program. Police could use iris recognition tools to identify missing people. Or police could use these same tools as part of broader programs of surveillance and “ethnic sorting” directed against ethnic minority communities. Iris scan collection has been a key part of state repression and mass detainment in Xinjiang, where police have created “multi-modal” biometric profiles of Uyghurs and other non-Han residents authorities view as potential threats to social stability.

Police could also use the collection of iris scans or other biometric data as a way to deepen control over critics of the Chinese state. This deepening of control already appears to be happening. Following protests in late 2022 across China against harsh pandemic control measures, police collected the “retina patterns” of demonstrators held in police custody, while in other cases police used surveillance cameras equipped with facial recognition capabilities to identify protesters and warn them against participating in future demonstrations.

However police decide to use population-wide iris scan databases or iris recognition technologies, it is clear that these tools will strengthen existing forms of police surveillance. Police already maintain population databases of target people. By associating iris records with personal files in these population databases, police can potentially identify anyone they have on record simply by scanning their eyes. These population databases are in some cases also linked to computer systems at hotels, railways, and airlines. Chinese airports and some municipal transit systems are already using facial recognition cameras for the purpose of passenger screening and payment. If these institutions increasingly use iris recognition terminals to verify customer or passenger identity, Chinese citizens viewed by the police as threats to the party-state may find it even more difficult to travel without alerting the police.

Further contributing to the potential human rights impact of this program is the character of policing in China. China’s police are required to be loyal to the ruling Communist Party. To that end, domestic security work in China involves both policing crime and repressing political opponents. However, the line separating crime control and political repression is often fuzzy. Authorities have charged feminists, labour activists, and human rights lawyers with “picking quarrels and provoking troubles,” “disturbing public order,” and “subversion of state power.” And as part of anti-crime campaigns, police in China also used their extensive authority to detain people with or without charge to punish both political critics and ethnic minorities. Without opposition political parties, independent courts, a free press, or civil society organizations capable of checking police powers, police in China will be free to collect and use iris scans from whomever they choose and for whatever purpose they wish.

The threat that unrestricted police iris scan collection poses to human rights and privacy is not unique to China. During the United States’ occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq, US military collection of iris scans from local residents was a key surveillance tool. The FBI is also interested in the potential applications of iris recognition technologies and iris scan databases.

Compulsory collection of iris scans by state actors may be in violation of key human rights documents. Article 17(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that “[n]o one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation,” while Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “[n]o one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation.”

Police iris scan collection can also have a chilling effect on civil society. People who have their irises scanned may have no further encounters with the police. However, as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression David Kaye warned in his 2019 report on surveillance and human rights:

“In environments subject to rampant illicit surveillance, the targeted communities know of or suspect such attempts at surveillance, which in turn shapes and restricts their capacity to exercise the rights to freedom of expression, association, religious belief, culture and so forth. In short, interference with privacy through targeted surveillance is designed to repress the exercise of the right to freedom of expression.”

It is also possible that even properly functioning iris recognition tools or iris scan databases will play only a modest role in crime control, despite the claims of proponents. As the United Kingdom’s then-Biometrics Commissioner Paul Wiles noted in a 2017 report, “[i]t does not follow that where crimes are detected or ‘solved’ by the police, all those detections where biometrics were available occurred because of a biometric match: the offender may have been identified for other reasons and the biometric holdings may have played no role or were merely confirmatory.”

Presently, there is a lack of international norms concerning police collection, storage, and use of biometric data like iris scans. At the global level, states, civil society groups, researchers, and international organizations should work together to establish relevant norms and support mechanisms that monitor adherence to these norms and identify possible violations. At the national level, states – including China – must enact and enforce strict limits on police collection, analysis, and storage of iris scans and other sensitive biometric data, in order to minimize the potential harm to those from whom data were collected, their kin, and their wider community.

Acknowledgements

Research for this project was supervised by Professor Ron Deibert.

We would like to thank Donald Clarke, Ron Deibert, Jeff Knockel, Michael Kovrig, Yves Moreau, Tenzin Norgay, Maya Wang, and one anonymous reviewer for valuable feedback.

Sources

Primary sources collected for this project are available here.

![Mass Iris Scan Collection in Qinghai: 2019–2022 10 Figure 9: Police collect iris scans from elderly people. “[Work Dynamics] Service at home, providing greater convenience at no distance” April 16, 2020, The Paper.](https://citizenlab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/image13-edited.png)