Not OK on VK

An Analysis of In-Platform Censorship on Russia’s VKontakte

This report examines the accessibility of certain types of content on VK (an abbreviation for “VKontakte”), a Russian social networking service, in Canada, Ukraine, and Russia. Among these countries, we found that Russia had the most limited access to VK social media content, due to the blocking of 94,942 videos, 1,569 community accounts, and 787 personal accounts in the country.

Key Findings

- This report examines the accessibility of certain types of content on VK (an abbreviation for “VKontakte”), a Russian social networking service, in Canada, Ukraine, and Russia.

- Among these countries, we found that Russia had the most limited access to VK social media content, due to the blocking of 94,942 videos, 1,569 community accounts, and 787 personal accounts in the country.

- VK predominantly blocked access to music videos and other entertainment content in Canada, whereas, in Russia, we found VK blocked content posted by independent news organizations, as well as content related to Ukrainian and Belarusian issues, protests, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ) content. In Ukraine, we discovered no content that VK blocked, though the site itself is blocked to varying extents by most Internet providers in Ukraine.

- In Russia, certain types of video content were inaccessible on VK due to the blocking of the accounts of the people or communities who posted them. These individuals and groups were often targeted for their criticism of Russia’s President Vladimir Putin or of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Additionally, accounts belonging to these communities and people have been restricted from VK search results in Russia using broad, keyword-based blocking of LGBTIQ terms.

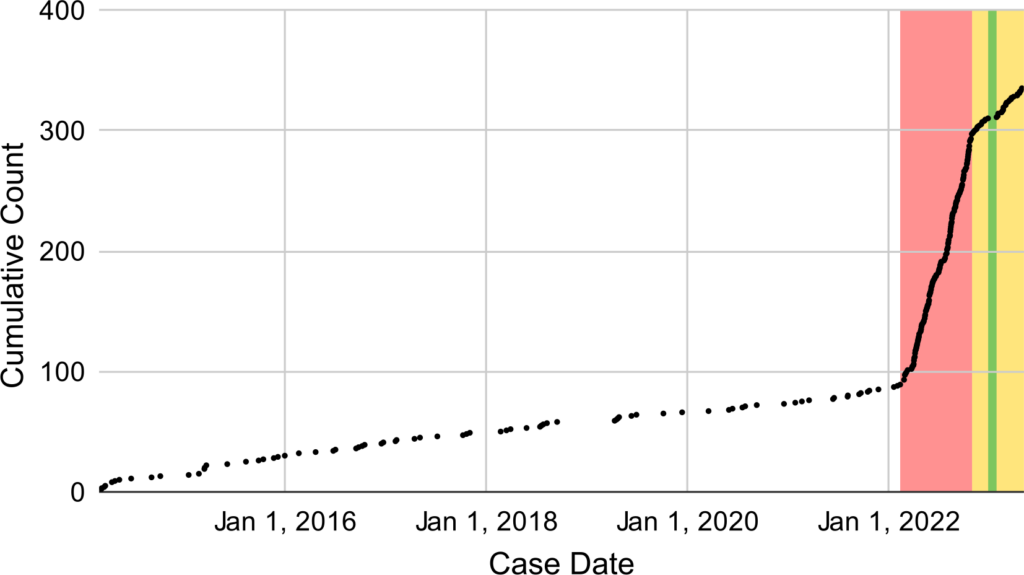

- We collected over 300 legal justifications which VK cited in justification of the blocking of videos in Russia. Notably, we discovered a 30-fold increase in the rate of takedown orders issued against VK in an eight month period following Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Introduction

While China is known for fostering its own ecosystem of social media platforms such as the chat app WeChat and microblogging platform Weibo and blocking their American counterparts (e.g., WhatsApp and Twitter), Russia has allowed access to WhatsApp and Twitter, but has also put a considerable effort into deploying and promoting Russian equivalents. For example, VK and Odnoklassniki, which are roughly Facebook equivalents, Rutube, a Russian equivalent of YouTube, and Yandex which is equivalent to Google Search. In 2022, Runniversalis, a pro-Kremlin version of Wikipedia was launched, reminiscent of Chinese efforts such as Baidu Baike to create a domestic clone of Wikipedia. Although many North American social media platforms remain accessible in Russia, Russia eventually blocked Facebook and Twitter following the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Chinese social media platforms, which are known to apply pervasive political and religious censorship to their Chinese users, take a variety of approaches to treating their non-Chinese users who may have different expectations concerning freedom of speech. While many platforms such as Weibo apply their political censorship even to users outside of China, others such as WeChat, in a bid to try to appeal to non-Chinese users, apply fewer speech restrictions to them. Other companies, such as Bytedance, take the approach of maintaining distinct platforms inside China (Douyin) versus elsewhere (TikTok). Like Chinese platforms, Russian platforms are also known to perform political censorship. However, the mechanisms the latter use to apply censorship, what topics they censor, and if or how those mechanisms apply to users outside of Russia are issues that are still understudied in the research on information controls.

Internet censorship in Russia is enforced through a variety of legal mechanisms. The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (Roskomnadzor), as the Internet regulator, maintains a centralized “blacklist” governing the blocking of IP addresses, domain names, and unencrypted HTTP URLs, which Internet service providers (ISPs) in Russia are legally obliged to implement. However, the censorship of social media content, which, due to HTTPS encryption, cannot be individually blocked by ISPs, is maintained through other legal mechanisms such as court orders. Multiple government (e.g., the Roskomnadzor and the office of the Prosecutor General) and non-government agencies (e.g., Rosmolodezh, the Federal Agency for Youth Affairs) can apply for a court order to have websites blocked, in which they typically appeal to one of Russia’s multiple laws governing Internet content. These laws often contain vague terms concerning the content they prohibit, including “нарушением установленного порядка” [violation of the established order], “нецензурную брань” [obscene language], “явное неуважение к… органам, осуществляющим государственную власть в Российской Федерации” [blatant disrespect for… bodies exercising state power in the Russian Federation], and “Пропаганда нетрадиционных сексуальных отношений и (или) предпочтений” [propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations and (or) preferences]. These laws have been used to justify political censorship of Internet content, particularly content critical of Putin or other Russian leadership, and to justify the restriction of the rights of LGBTIQ communities. Furthermore, according to a law which went into effect in February 2021, social media platforms are required to implement blocking proactively, as opposed to merely in response to court orders. Previous research studying Chinese social media censorship has shown how deferring blocking decisions to the private sector gives rise to inconsistent blocking across companies, with platforms often “overblocking” to ensure that they have covered all of the bases to avoid legal repercussions for insufficiently blocking content.

In this report, we study VKontakte [ВКонтакте], commonly abbreviated as “VK,” which is the most popular social media platform in Russia. VK is similar to Facebook in that it provides personal accounts, messaging, music and video hosting, and other community features. The platform is divided into three broad organizational categories: videos, communities or clubs, and people. VK has a complicated history concerning Russian censorship. The platform was founded in 2006 by Pavel Durov, who is also known for founding Telegram Messenger. Durov was dismissed as VK’s chief executive officer (CEO) in 2014, allegedly for failing to hand over the data of Russian political protesters to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), the country’s security agency. Durov was also targeted for failing to ban a VK community advocating for Alexei Navalny, a political opponent of Putin. Durov additionally claimed that the platform had come under “full control” of “Kremlin insiders” after the platform was sold to Alisher Usmanov, an oligarch loyal to Putin. In 2021, VK’s then-CEO Boris Dobrodeev resigned following the takeover of the company by state-owned companies. Analysts speculated that this state takeover could lead to “greater interference” by the Russian government.

In addition to criticism due to censorship, VK has been criticized by the digital security community as a platform that is unsafe for activists. This allegation was made on account of the personal information which it collects and due to VK joining the Register of Organizers of Distribution of Information in the Internet Network, a special list of platforms that must provide user data on request to the FSB and Russian police. Several waves of “exodus” of users from VK have been documented — the earliest one corresponding to the year of Durov’s departure — due to fears of government surveillance and legal harassment.

In this work, we are interested in measuring how VK implements political censorship in the context of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that began in February 2022. Our research includes identifying what mechanisms VK uses to enforce censorship, what type of content is censored, and if or how this censorship applies to users outside of Russia. Specifically, we measure the accessibility of content on VK from different countries or vantage points to uncover instances of differential censorship, i.e., content which is censored in one region but not another. This allows us, for example, to determine which content is visible in Canada but not in Russia, and vice versa. In this report, we focus on comparing content availability from Russia, Ukraine, and Canada.

The remainder of this report is structured as follows: In the “Methodology” section, we detail our methods for uncovering VK’s differing censorship across countries, and, in “Experimental setup,” we explain the conditions and implementation details in which we executed these methods. Furthermore, in “Results,” we reveal our findings concerning the pervasive political and social censorship which VK applies to users in Russia. In “Limitations,” we review the limitations of our experiment, and finally, in “Discussion,” we discuss how our findings contribute to a greater understanding of Internet censorship in Russia and how Russian social media censorship compares to censorship elsewhere.

Methodology

This section details our methodology for measuring differential censorship on VK across Canada, Ukraine, and Russia. We conducted our research entirely without registration of or interaction with any user accounts on the VK platform. Instead, we tested access from network vantage points in the regions that we chose to compare, comparing the differences in what content was accessible in each region on VK’s website. This method ensures that we can conduct our testing without obtaining SIM cards or phone numbers, without worrying about account termination, and without the ethical concerns of creating or transmitting content over the platform.

To test for differential censorship on VK, and to ensure that we have a diverse sample of popular, easily enumerable topics to query, we sampled from Wikipedia article titles. We began by selecting the following six language editions of Wikipedia: Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Georgian, Chechen, and Kazakh. We selected these language editions because VK is a Russian platform, and these are languages commonly spoken both within and in areas surrounding Russia. For each of these Wikipedia language editions, we independently sorted their articles by the total number of views that they had during January, February, and March 2023, sorting them in descending order of popularity. In our testing, we drew from across these six sorted lists in a round-robin fashion such that we tested the same number of articles from each language edition of Wikipedia.

In this work, we are interested in comparing the availability of VK content across Canada, a liberal democracy where we are based, as well as Russia and Ukraine, the countries with the first and third largest number of visitors to VK, respectively. VK allows for searching for videos, communities (also called groups or clubs), and people. As such, for each article title that we tested, we performed nine search queries simultaneously on the VK website. For each of the countries of Canada, Ukraine, and Russia and for each of the videos, communities, and people search targets, we queried the article title on that search target in that country. For each of these nine combinations, we recorded the number of search results for the query.

As we noticed that VK would on occasion spuriously report a smaller number of results than what it ordinarily would for a query, we implemented the following retest procedure. Twenty-four hours following an original query, we repeated searching the query from the same vantage point on the same search target. We then recorded whichever is greater of the number of results reported in the retest and the number of results reported in the original test.

Next, we sought to establish some threshold under which we could label the search result numbers from two different regions as suspiciously different. We noticed that comparing absolute numbers favored finding queries which had large numbers of results as suspiciously different, whereas comparing by the percent difference favored finding queries which had small numbers of results as suspiciously different. As such, to test whether the number of search results x from one region is suspiciously less than the number of results y from another region, we employ the following statistical heuristic. We noticed early on by analyzing the initial results between Canada and Ukraine that they were consistent modulo random fluctuation. In an early sample, we saw that in 132 of the tests there were eight which had a different number of results, each with a difference of one. As we did not know the variables affecting these random fluctuations (i.e., is or to what extent is the size of the fluctuation proportional to the number of results?), we chose 8/132 as a clear upper bound for the proportion of results we would find missing by chance. Using a one-sided chi-squared test, we then performed a test of difference in proportions, namely, the hypothesis that (x – y) / x ≤ 8/132. If we reject this hypothesis, with p < 0.001 probability that such a difference in proportions could have arisen by chance, we conclude that x is suspiciously missing results compared to y.

For search result numbers that seemed to be suspiciously missing results, we further explored which content was missing from their results. Since VK only allows revealing up to 999 search results for a query, we limited our investigation to queries with fewer than 1,000 results. For any number of results x and number of results y, if x < 1,000, y < 1,000, and either x or y are suspiciously missing results compared to the other, we downloaded all of the search results for both x and y and recorded which were missing from each.

For each result missing from our case studies, to better understand why that video, community, or person was missing from the results for that country, we attempted to access that result from the region in which it was missing. For example, we attempted to access the result using both the desktop (vk.com) and mobile (m.vk.com) versions of the VK website. We recorded any error message or other block message which was displayed to the user. Specifically for missing video results, we attempted to access additional pages from that country. A video on VK can be associated with an individual poster, a community poster, or both. To better understand why videos are missing, we also attempted to access their individual and community posters and recorded any error or block message displayed on their pages. We attempted access to these pages using both the desktop (vk.com) and mobile (m.vk.com) versions of the site.

Experimental Setup

We implemented the above methodology in Python using the aiohttp and SciPy modules and executed the code on an Ubuntu 22.04 Linux machine. We performed this experiment from April 17 through May 13, 2023. Our Canadian measurements were performed from a University of Toronto network. Our Russian and Ukrainian measurements were performed through WireGuard tunnels, as provided by a popular VPN service offering Russian and Ukrainian vantage points. In light of VK being blocked to varying extents on most Ukrainian networks due to a ban of the site, we confirmed that our Ukrainian vantage point had access to VK before performing our experiments (see Appendix A for our analysis of Ukraine’s ban of VK).

Results

During our testing period, we tested on VK the accessibility of the titles of the top 127,187 articles in each of the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Georgian, Chechen, and Kazakh language Wikipedias. Together, this sample set comprised 708,346 unique article titles. By measuring what content was blocked in VK search queries for these titles, we found differential blocking of videos in Canada, as well as of videos, communities, and personal accounts in Russia, although the motives for the blocking of videos in Canada versus Russia appeared starkly different, as we explain below. We also found that in Russia, search query results for communities and people were censored by keyword, whereas in Canada we found no such filtering.

Notably, we found no in-platform differential blocking carried out by VK in Ukraine compared to Canada or in Ukraine compared to Russia. Since we did not discover any content that was accessible in Canada or Russia but that was inaccessible in Ukraine, in the remainder of this section, we will focus on comparing differential blocking in Russia compared to Canada and vice versa. We first provide an overview of our findings and detail the different blocking mechanisms that VK uses. We then use data analysis techniques to better understand the blocked content that we discovered, such as what type of content was blocked, what events precipitated its blocking, or what legal justifications did VK cite in its blocking.

Blocking Overview and Mechanisms

From our results, we were able to infer that VK used multiple methods of blocking. The primary method seen was the blocking or removal of certain search results. For content missing in Canada, for example, we saw no missing personal account results. Nine communities were missing from Canadian search results, but the results themselves were still accessible in Canada by typing the URLs for the communities’ pages, and there did not appear to be anything about them that would suggest why they might be removed from search results. As such, we believe that they were false positives in that they were missing from the search results for completely benign reasons such as different load balancers or caching servers possessing inconsistent views of the same data. Aside from a small number of what also seemed to be false positives, all of the 2,613 videos tested in Canada that were missing from the search results showed either a “This video is unavailable in your country” or a “Video sound unavailable” block message. These videos appeared to all be popular sports, music, and other entertainment videos posted by ordinary users and, when considering the explanation given in their block messages, these videos were likely blocked in Canada for copyright infringement. These videos, however, were still available in Russia. Our hypothesis is that this differing treatment of copyright-infringing content could be explained by the overall inconsistent way that VK enforces copyright law across multiple regions.

| Ukraine | Canada | Russia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Videos | None observed | Copyright infringement targeting videos | When a community or person posting a video is blocked, that video is also blocked |

| Communities | None observed | None observed | (1) LGBTIQ keyword-based blocking of search queries for communities and (2) political blocking of communities |

| People | None observed | None observed | (1) LGBTIQ keyword-based blocking of search queries for people and (2) political blocking of people |

For each region, for each content type, the methods of blocking which we discovered.

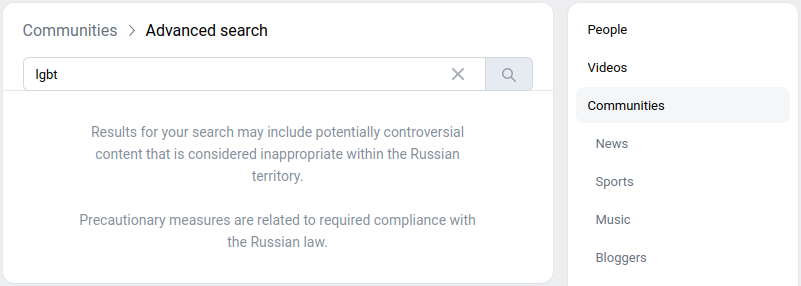

We observed more diverse methods and motivations behind content being unavailable in Russia (see Table 1 for a summary). When searching for communities and people, we observed that VK disabled search results if the search query contained certain LGBTIQ-related keywords (see Figure 1 for an illustration and Table 2 for a list of the keywords which we discovered triggering filtering). While it applied for searches for communities and people, this keyword-based censorship of search queries did not appear to apply to searches for videos.

| Keyword | English Translation |

|---|---|

| gay | gay |

| LGBT | LGBT |

| Геи | gay |

| Гей | gay |

| ЛГБТ | LGBT |

| ЛГБТК | LGBTQ |

| Лесбиянка | lesbian |

| Трансгендер | transgender |

| Фембой | femboy |

Keywords censoring search queries for communities and people in Russia.

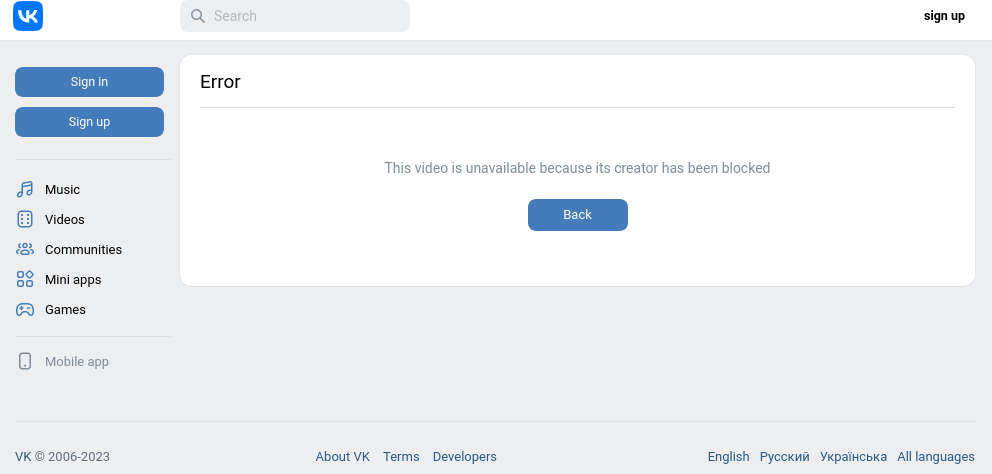

Aside from VK’s keyword-based filtering of searches for community and personal accounts, VK also directly blocked individual community and personal accounts, which also hides them from search results and displays a block message when viewing the account’s page. In fact, blocking community and personal accounts appears to be VK’s primary method of censoring videos in Russia. Outside of 134 videos which displayed no block message and which we believe to be false positives, the remaining 94,942 videos missing from search results showed a block message on the desktop version of VK such as “This video is unavailable because its creator has been blocked.” We confirmed that all of these videos were blocked due to the community or person who had posted the video being blocked, because when we attempted to view the community or the account that posted these videos, we received a block message that mentioned a court order for the blocking.

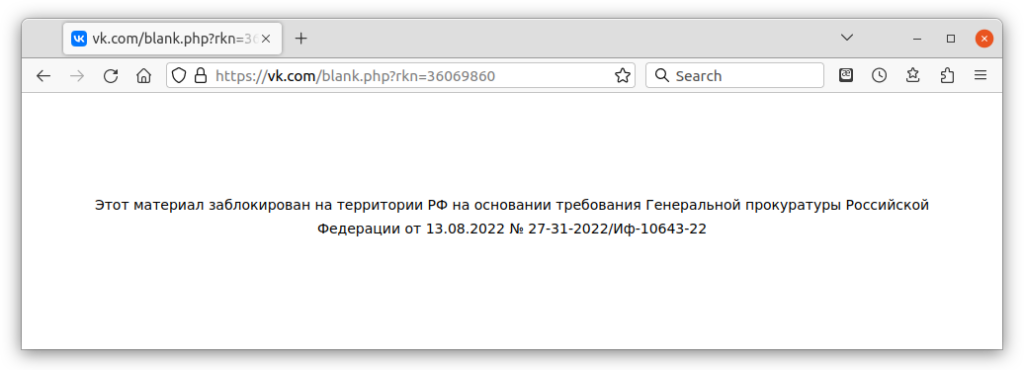

To justify the blocking of communities and personal accounts in Russia, we observed 336 unique VK block messages citing 303 different legal case numbers. An example of such a block message is as follows: “Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании решения суда/уполномоченного федерального органа исполнительной власти (Центральный районный суд г. Хабаровска – Хабаровский край) от 10.08.2015 № 2-5951/2015” [This material was blocked in the territory of the Russian Federation on the basis of the decision of the court / authorized federal executive body (Central District Court of Khabarovsk – Khabarovsk Territory) dated 10.08.2015 No. 2-5951/2015]. In instances where information is publicly available, these legal cases appear to be takedown requests filed by Russian prosecutors or other actors, which appeal to varying Russian laws for justification. For example, in the case cited in the aforementioned block message, the Russian prosecutor appeals to Article 4 of a Russian law “On Mass Media” to ask the court to order the takedown of content on VK which allegedly uses obscene language to refer to Vladimir Putin.

While the desktop version of VK consistently showed the message “This video is unavailable because its creator has been blocked” when a community or person posting the video was blocked, we found that, on the mobile version, if the video was posted by a community blocked in Russia (as opposed to a personal account), then it shows the block message of the blocked community instead. It is unclear why this inconsistency exists.

We also rarely observed other error messages which were not block messages such as “Please sign in to view this video,” “Access to this video has been restricted by its creator,” and “This page has either been deleted or not been created yet.” These messages were not indicative of blocking but rather would occur if content were deleted or restricted at the poster’s discretion during our testing process. Therefore, we did not consider such content with these error messages to be blocked. See Table 3 for a breakdown of the types of error messages which we observed.

| Error Message Type | Example(s) | Observed in? | Block Message? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Court ordered blocking | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании решения суда/уполномоченного федерального органа исполнительной власти (Центральный районный суд г. Хабаровска – Хабаровский край) от 10.08.2015 № 2-5951/2015” [This material was blocked in the territory of the Russian Federation on the basis of the decision of the court / authorised federal executive body (Central District Court of Khabarovsk – Khabarovsk Territory) dated 10.08.2015 No. 2-5951/2015] | Russia | Yes |

| The community or person posting this video has been blocked | “This video is unavailable because its creator has been blocked” | Russia | Yes |

| Copyright infringement | “This video is unavailable in your country” “Video sound unavailable.” | Canada | Yes |

| Permission denied | “Please sign in to view this video” “Access to this video has been restricted by its creator” | Canada, Russia | No |

| Deleted | “This page has either been deleted or not been created yet.” | Canada, Russia | No |

Breakdown of types of error messages, examples of them, where they have been observed, and whether they are block messages identifying differential blocking.

While earlier we found blocked communities and personal accounts due to their results missing in search results, we can also find them from looking to see who posted blocked videos. Working backward from blocked videos to find the blocked communities or personal accounts who posted them, we found an additional 826 communities and 768 personal accounts blocked in Russia. Together with 804 blocked communities and 19 blocked personal accounts directly missing from community and people search results, we found 1,569 unique communities and 787 unique personal accounts blocked in Russia (see Table 4 for a summary of all content blocked).

| Method of Discovery | Canada: Missing in Results (Unique) | Blocking a Video (Unique) | Total (Unique) | Russia: Missing in Results (Unique) | Blocking a Video (Unique) | Total (Unique) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Videos | 2,613 | N/A | 2,613 | 94,942 | N/A | 94,942 |

| Communities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 804 | 826 | 1,569 |

| People | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 768 | 787 |

For each region, for each content type, the number of blocked instances of that content type in that region. For communities and personal accounts, we further break down the number we discovered from their absence in search results versus for having posted a blocked video.

While we have given a brief overview of the types of blocking methods on VK, as well as the amount of content subject to each type of blocking across different regions, in the remainder of this section we will perform a deeper analysis of the type of content blocked on VK. We will first characterize blocked videos in Canada and Russia according to the search queries from whose results they were missing, the posters of the blocked videos, and a random sampling of the blocked video contents themselves. Then, we analyze the block messages and legal justifications which VK communicates to the user upon attempting to view blocked content.

Analysis of Blocked Videos

In this section, we characterize blocked videos according to the search queries from whose results they were missing, the posters of the blocked videos, and a random sampling of the contents of the blocked videos themselves.

What Search Queries Discovered Blocked Videos?

Recall that, during our testing, we took popular Wikipedia article titles from multiple language editions of Wikipedia and used them to search for videos, communities, and personal accounts on the VK website, to see if and to what extent these search results were blocked in one region versus another. In this section, we are specifically interested in the search queries that led to the discovery of large numbers of blocked videos, as such queries can signal the type of content blocked on VK. We call such queries productive queries.

Videos Blocked in Russia

Among the top ten most productive queries (i.e., those leading to the discovery of the greatest number of blocked videos), we see that most are related to the Ukraine war (“Учасники російсько української війни Ш” [Participants of the Russian-Ukrainian war], “Пропаганда війни в Росії” [Propaganda of War in Russia]) and international bodies that are involved in mediating the conflict (“Генеральна Асамблея ООН” [UN General Assembly], “Міжнародний суд ООН” [International Court of Justice]).

The most productive queries in Russia can be understood to be indirectly related to the war such as “Secret Invasion,” derived from a Wikipedia article for a Marvel comic series turned TV show, but nevertheless uncovering blocked content related to the Ukrainian “invasion” more broadly, and “Катэгорыя 24 лютага” [Category: February 24], the title of a Wikipedia article listing holidays on February 24 but which is also the day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. There are also productive queries related to Ukraine more generally such as “Поліський район” [Polskiiy District], a former administrative region in Kyiv Oblast, and the anthem of Ukrainian President Volodomyr Zeleskyys home town “Кривий Ріг” [Kryvyi Rih]. We also found one term related to a news service in Belarus (“БелаПАН” [BelaPAN]), as well as one term which appeared unrelated to the conflict (“Чорні троянди” [Black Roses]) but upon closer inspection we discovered that it was the name of a blocked Ukrainian pro-military group which had posted a large number of videos.

| Rank | Query | Translation | Description of Page | Query Language | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Total Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Чорні троянди | Black Roses | Turkish rose plants | Ukrainian | 493 | 904 |

| 2 | БелаПАН | BelaPAN | Private news agency in Belarus | Belarusian | 476 | 843 |

| 3 | Кривий Ріг моє місто | Kryvyi Rih – my city | Anthem of Ukrainian town | Ukrainian | 450 | 493 |

| 4 | Пропаганда війни в Росії | Propaganda of War in Russia | Description of Russian War Propaganda | Ukrainian | 449 | 625 |

| 5 | Генеральна Асамблея ООН | UN General Assembly | United Nations General Assembly | Ukrainian | 424 | 798 |

| 6 | Міжнародний суд ООН | International Court of Justice | United Nations International Court of Justice | Ukrainian | 419 | 807 |

| 7 | Учасники російсько української війни Ш | Participants of the Russian-Ukrainian war | Description of the conflict | Ukrainian | 346 | 453 |

| 8 | Сакрэтнае ўварванне | Secret invasion | Marvel Mini Series | Belarusian | 322 | 358 |

| 9 | Поліський район | Polskiiy District | Former region of Ukraine in Kyiv Oblast | Ukrainian | 314 | 356 |

| 10 | Катэгорыя 24 лютага | Category: February 24th | An index of holidays on February 24th | Belarusian | 293 | 363 |

The ten most productive queries in Russia, i.e., those which we tested which discovered the most blocked videos in Russia.

Videos Blocked in Canada

In contrast to the test results from Russia, the most productive queries in Canada did not deal with the Ukraine war but rather sports, music, and geographic locations. Most of the queries (six in ten) are related to sports including: The Davis Cup (in Russian and Belarusian), World Figure Skating Championships, and three different soccer players (Ciro Immobile, Alejandro Gomez, and Duván Zapata). There are also queries related to music (K Ci & JoJo and Beatles Bootleg Recordings) and geographic locations (Locust and Charleroi). The queries that led to blocked content in Canada are different from those in Russia and are more focused on entertainment rather than current events.

| Rank | Query | Translation | Description of Page | Query Language | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Total Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Локаст | Locust | City in the United States | Chechen | 161 | 284 |

| 2 | Кубок Дэвиса | Davis Cup | The Davis Cup tennis trophy | Russian | 123 | 457 |

| 3 | Иммобиле Чиро | Ciro Immobile | Italian soccer player | Russian | 78 | 194 |

| 4 | Шарлеруа | Charleroi | City in Belgium | Ukrainian | 59 | 285 |

| 5 | K Ci JoJo | K Ci & JoJo | Musicians | Georgian | 57 | 251 |

| 6 | Чемпионат мира по фигурному катанию 2023 | World Figure Skating Championships 2023 | Figure skating event | Russian | 55 | 157 |

| 7 | Кубак Дэвіса | Davis Cup | The Davis Cup tennis trophy | Belarusian | 54 | 456 |

| 8 | The Beatles Bootleg Recordings 1963 | The Beatles Bootleg Recordings 1963 | Compilation Beatles album | Georgian | 53 | 253 |

| 9 | Алехандро Гомес | Alejandro Gomez | Argentine soccer player | Ukrainian | 52 | 258 |

| 10 | Сапата Дуван | Duván Zapata | Colombian soccer player | Russian | 52 | 77 |

The top ten most productive queries in Canada, i.e., those which we tested which discovered the most blocked videos in Canada.

What Languages are Blocked Videos in?

In the previous section, we looked at the search queries that led to the discovery of large numbers of blocked videos. In this section, we perform a similar analysis but based on which language edition of Wikipedia the search query was from. Our purpose is to see which Wikipedia language edition’s article titles led to the largest numbers of blocked videos. We do this to better understand the languages of the video content blocked on VK.

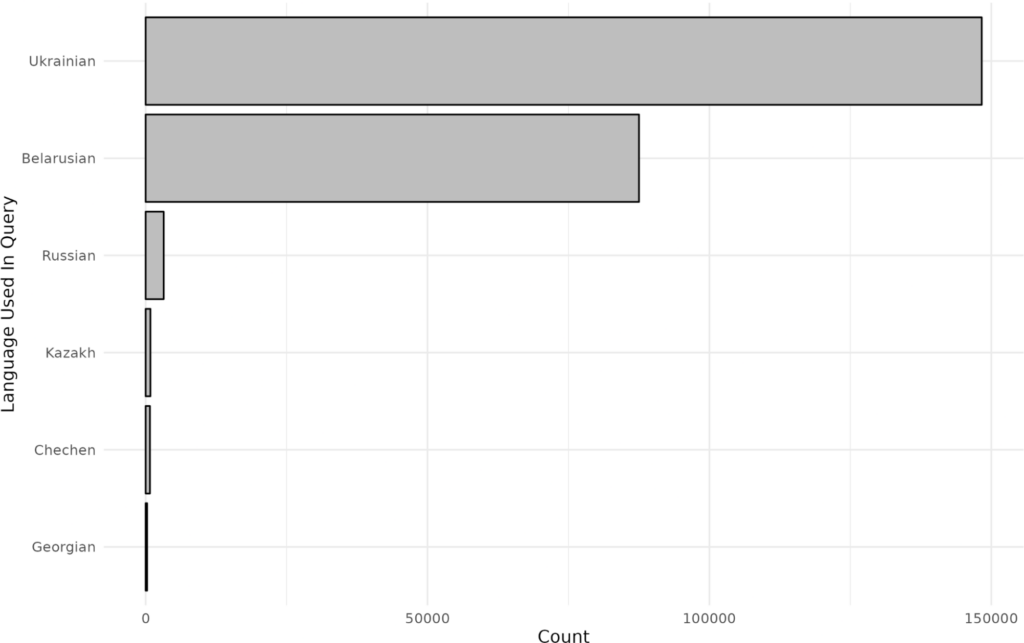

Videos Blocked in Russia

Among videos blocked in Russia, we find that queries from the Ukrainian language Wikipedia discovered the largest share (61%) of blocked video results, followed by Belarusian (36%), with Russian at a distant third (1%). All remaining languages (Kazakh, Chechen and Georgian) accounted for less than 0.3% each. Seeing a disproportionately large amount of Ukrainian content blocked is surprising because, after VK’s 2017 blocking in Ukraine, average daily visits from Ukrainian users dropped from 54% of Ukrainian Internet users to only 10% of Ukrainian Internet users visiting VK on a given day. Moreover, despite VK being a Russian social media platform, Russian language queries in Russia led to the discovery of only a small share of blocked videos (1.33%). However, these findings may merely speak to the effectiveness of VK’s censorship regime at disincentivizing Russians and, therefore, largely Russian speaking users to engage in censored speech. Furthermore, the social cost of being blocked in Russia is greater for Russians than for those outside of Russia, again further disincentivizing sensitive political speech for users in Russia.

| Language | # of Queries | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | 148,313 | 61.56% |

| Belarusian | 87,521 | 36.33% |

| Russian | 3,205 | 1.33% |

| Kazakh | 854 | 0.35% |

| Chechen | 760 | 0.32% |

| Georgian | 264 | 0.11% |

For videos found blocked in Russia, the number of videos discovered via queries originating from which language edition of Wikipedia.

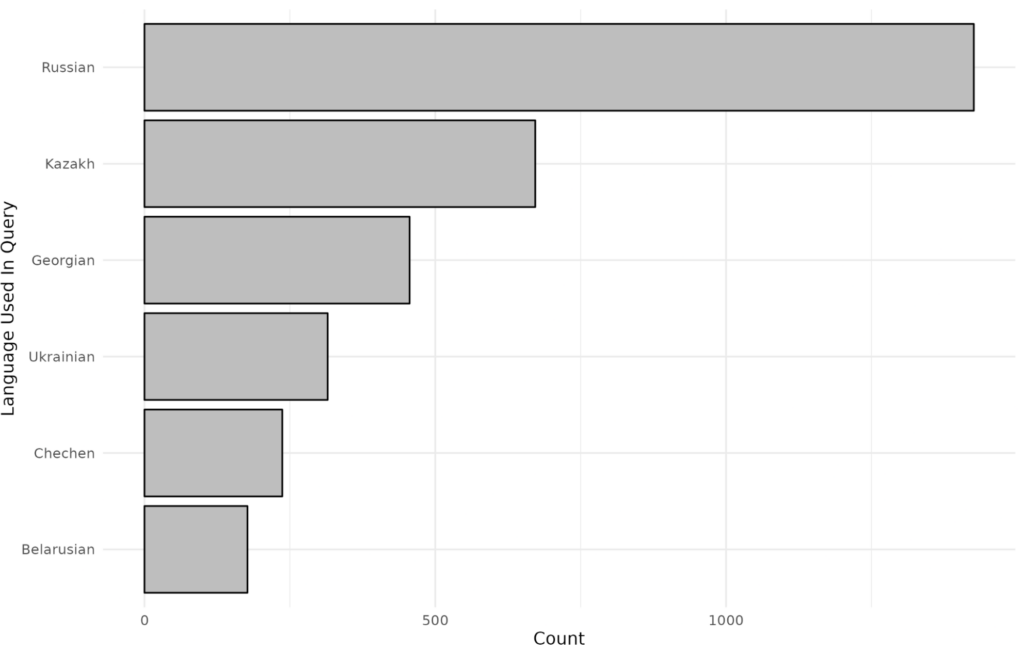

Videos Blocked in Canada

In contrast to Russia, which blocked a large share of videos queried using titles article from the Ukrainian language Wikipedia, the language composition of the queries that led to the discovery of blocked videos in Canada is markedly different. Among the videos blocked in Canada, the Russian language is most represented in our data set with 43.44% share of results, followed by Kazakh (20.47%) and Georgian (13.89%) All remaining languages (Ukrainian, Chechen, and Belarusian) have less than a ten percent share. In Canada, Russian is far more represented (43.34% in Canada compared to 1.33% in Russia). This finding is more in line with expectations as VK is a Russian social media platform with a predominantly Russian user base and, therefore, such a platform would contain more Russian language content in requirement of moderation than any other language.

These findings reflect VK’s differing motivations in blocking videos in Russia versus Canada. In Russia, VK appears motivated to block content that primarily contains certain political views, which are often expressed by Ukrainian and Belarusian speakers. However, in Canada, VK blocks content that contains copyright infringement, which we would expect to be committed by speakers of different languages of equal frequency. As VK is a Russian platform we therefore would expect to see higher absolute numbers of Russians moderated due to their greater representation on the platform.

| Language | # of Queries | Share |

|---|---|---|

| Russian | 1,426 | 43.44% |

| Kazakh | 672 | 20.47% |

| Georgian | 456 | 13.89% |

| Ukrainian | 315 | 9.59% |

| Chechen | 237 | 7.22% |

| Belarusian | 177 | 5.39% |

For videos found blocked in Canada, the number of videos discovered via queries originating from which language edition of Wikipedia.

Who Posted Blocked Videos?

Next, we review who posted the largest share of the most blocked content that we discovered on VK to get a sense of the individuals or entities whose content is most affected by VK’s blocking and what they are posting. We divide our examination into two different user types per country: videos that were posted by personal accounts and those posted by communities. It should be noted that some community pages may have the branding of a company but it is not always clear if these are officially operated accounts. VK offers a verification system for companies and brands, but verification is optional, and some companies may be unaware or unwilling to go through this process. In our discussion, we will mention whether a company is verified.

Videos Blocked in Russia Posted by Personal Accounts

From examining the videos that were blocked in Russia, we discovered 1,429 personal accounts that were blocked in the country. Among these, one poster named “Oleg Skripnik” accounts for an outsized portion (37%) of the blocked videos that we discovered, followed by “Daryna Ivaniv” (12%) and “Podryv Ustoev” (4%). These top three posters account for 53% of all videos that we discovered were posted by blocked personal accounts, underscoring how a small number of posters are overrepresented in terms of video blocking. Among the personal accounts that were blocked, the majority of these accounts post political content only occasionally and cannot be described as accounts primarily used for activism. A few personal accounts that were blocked seem to belong to the Ukrainian military and are still active. This finding shows that, regardless of wide criticism of VK as an insecure, pro-Russian platform, and, in spite of its blocking in Ukraine (see Appendix A), it is still used by many Ukrainians including those currently on the frontlines.

| Rank | Profile URL | Account Name | Content Posted | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | https://vk.com/skripoleg | Oleg Skripnik | Ukraine war content | 19,061 | 37.93% |

| 2 | https://vk.com/id576554975 | Daryna Ivaniv | Ukraine war content | 6,328 | 12.59% |

| 3 | https://vk.com/s.krupko63 | Podryv Ustoev | Ukraine war content | 2,131 | 4.24% |

| 4 | https://vk.com/id613313976 | Daryna Ivaniv | Ukraine war content | 1,228 | 2.44% |

| 5 | https://vk.com/id229910131 | Masha Vedernikova | Ukraine war content | 1,193 | 2.37% |

| 6 | https://vk.com/id303073458 | Boris Suslenskiy | Ukraine war content | 1,005 | 2.00% |

| 7 | https://vk.com/id157885457 | Lyubov Platonova | Ukraine war content | 770 | 1.53% |

| 8 | https://vk.com/id293387897 | Vasily Zhazhakin | Ukraine war content | 690 | 1.37% |

| 9 | https://vk.com/id129054771 | Igor Zachosa | Ukraine war content | 604 | 1.20% |

| 10 | https://vk.com/id22401146 | Sergey Derkach | Ukraine war content | 568 | 1.13% |

The ten personal accounts which we discovered with the most blocked videos in Russia.

In addition to the 1,429 blocked personal accounts found via blocked videos, when we directly searched different article titles within the “People” category, we found an additional 19 blocked personal accounts due to being missing from our search query results. These additional accounts are all related to the Praviy Sektor, which is a Ukrainian nationalist group, except one account titled “Femboy Developer” (see Table 10).

| Profile URL | Title |

|---|---|

| https://vk.com/id315585161 | Praviy-Sektor Zakarpattya |

| https://vk.com/id287586663 | Praviy-Sektor Shishaki-Ray-Org |

| https://vk.com/id241957654 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id253532397 | Praviy-Sektor Peremishlyani |

| https://vk.com/id303491180 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id257667002 | Praviy-Sektor Praviy-Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id459902176 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id247366231 | Praviy-Sektor Chechelnik |

| https://vk.com/ukrop24 | Praviy-Sektor Dikanka-Rayorg |

| https://vk.com/drogobych_ps | Drogobich Praviy-Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id244694134 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id289687245 | Praviy-Sektor Kolomia |

| https://vk.com/id248075744 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id297537442 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id284720470 | Praviy-Sektor Karlivka |

| https://vk.com/pszak | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/id406055235 | Praviy-Sektor Kolomia |

| https://vk.com/id366480496 | Pravy Sektor |

| https://vk.com/femboy_dev | Femboy Developer |

The profiles of the additional 19 blocked personal accounts which we discovered from their absence in search queries.

Videos Blocked in Russia Posted by Communities

We discovered 826 communities blocked by VK in Russia from the videos they posted, which were also blocked in Russia. Ten of these blocked communities are ranked below in Table 11 by the number of videos which we discovered blocked that were posted by them. These communities include those focused on news (“Ploscha”) and Ukrainian and Belarusian patriotic communities (“My Country Belarus,” “My Ukraine,” and “Patriots of Ukraine”). One account was of a regional Ukrainian television station Channel 1 – Urban First [Канал 1 – Первый Городской]. There are also accounts of oppositional media focused on Belarus, such as Belsat TV, Radio Svoboda and European Radio for Belarus. Among these, Belsat TV and Radio Svoboda are state funded by Poland and the United States, respectively, while European Radio for Belarus is independent. Of these accounts, only the account of European Radio for Belarus is “verified” through VK, although all of these groups post content from their respective community pages.

| Rank | Profile URL | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share | Content Posted | Account Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | https://vk.com/ploshcha | 23,265 | 18.00% | Belarus content | News Poster |

| 2 | https://vk.com/euroradio | 18,667 | 14.44% | Verified account of European Radio for Belarus, nonprofit media for Belarus | Media |

| 3 | https://vk.com/belsat_tv | 10,738 | 8.31% | Belsat TV, Polish state funded media for Belarus | Media |

| 4 | https://vk.com/majabelarus | 8,337 | 6.45% | Belarus content | Patriotic Community |

| 5 | https://vk.com/radiosvaboda | 7,354 | 5.69% | Radio Svoboda Belarus, US state media for Belarus | Media |

| 6 | https://vk.com/patrioty | 4,320 | 3.34% | Ukraine war content | Patriotic Community |

| 7 | https://vk.com/we.patriots | 3,681 | 2.85% | Ukraine war content | Patriotic Community |

| 8 | https://vk.com/1tv_kr_ua | 2,564 | 1.98% | Ukrainian Regional Television | Media |

| 9 | https://vk.com/ua.insider | 2,562 | 1.98% | Ukraine war content | Nationalist |

| 10 | https://vk.com/war_for_independence | 2,265 | 1.75% | Ukraine war content | Patriotic Community |

The ten communities which we discovered with the most blocked videos in Russia.

Outside of these top ten communities, there are other communities blocked, including Ukrainian media outlets such as Hromadske [Громадське] and BBC News Ukrainian, and a Belarusian opposition newspaper Nasha Niva [Наша Ніва]. The verified community of the team of Alexei Navalny is also blocked. We also found sport-related communities such as “FC Shakhtar” (a fan page of the Football Club Shakhtar from Donetsk) and By.Tribuna.com (the Belarusian branch of an international sport media Tribuna) among the results.

In addition to the 826 blocked communities which we found via their blocked videos, when we directly searched different article titles within the “Communities” category, we found an additional 804 blocked communities due to being missing from our search query results. We present the ten queries which led to the discovery of the most blocked communities in Russia in Table 12.

| Rank | Language | Query | Translation | Types of Communities | # of Communities Discovered Blocked | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Russian | Неодимовый магнит | Neodymium magnet | Sale of magnets to tamper with gas and water meters. | 72 | 8.94% |

| 2 | Russian | Европейская хартия местного самоуправления | European Charter of Local Self-Government | Pro-USSR regionalist groups | 54 | 6.71% |

| 3 | Kazakh | Сыпатай Саурықұлы | Sypatai Saurykuly | Sports wagering communities (query unrelated) | 50 | 6.21% |

| 4 | Russian | Фиктивный брак | Fictitious marriage | Communities to arrange fake marriages | 42 | 5.22% |

| 5 | Belarusian | Пуцін хуйло | Putin is a dick | Anti-Putin groups | 38 | 4.72% |

| 6 | Ukrainian | Кирило Лукаріс | Kyrylo Loukaris | Pill buying/selling (query unrelated) | 38 | 4.72% |

| 7 | Ukrainian | Національний корпус | National Corps | Nationalist communities | 36 | 4.47% |

| 8 | Russian | Партия националистического движения | Nationalist Movement Party | Nationalist communities | 31 | 3.85% |

| 9 | Georgian | Путин хуйло | Putin is a dick | Anti-Putin groups | 27 | 3.35% |

| 10 | Chechen | СагӀсена | Sarcenas | Ozempic sales (query unrelated) | 28 | 3.48% |

The ten queries which we tested which discovered the most blocked communities in Russia.

The query, which led to the discovery of the most censored communities, is related to the sale of Neodymium magnets (“Неодимовый магнит”), accounting for over 8% of the communities which we discovered blocked. The content of these community pages indicates that these are rare earth magnets that are marketed as being able to tamper with water and gas meters. One group’s description claims that using these magnets for this purpose are prohibited by law, which suggests the lack of consistent legal enforcement in these communities. Many of the other search queries are also related to potential scams, such as the arranging of fake marriages (“Фиктивный брак”), sports wagering, pill sales, and diet supplements. There are blocked communities of racist and nationalist groups present as well. There are also communities related to pro-USSR regionalist groups (e.g., Community of the KNVR of the Udmurt Region [Община КНВР Удмуртского Региона]). Finally, many of the queries and their blocked groups are critical of the government and insulting of Putin, as many are titled with the anti-Putin slogan “Пуцін хуйло” which translates to “Putin is a dick.”

The blocked communities appear to have a different content focus compared to blocked videos. Whereas blocked video content in Russia is largely related to the Ukraine war and Belarus, blocked communities are focused on potential scams. There is some crossover, however, as racist, nationalist content is blocked in both videos and communities within Russia.

Videos Blocked in Canada Posted by Personal Accounts

In contrast to Russia, within the top ten personal accounts that posted the most blocked videos in Canada, all except one primarily posted music content (see Table 13). There were no videos containing political or current events that were posted by the top ten posters in Canada. This result is, again, a departure from what was seen in Russia. Hence, VK in Canada focuses more on blocking entertainment content for what is most likely copyright-related justifications.

| Rank | Profile URL | Account Name | Content Posted | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | https://vk.com/ig.linevich | Igor Linevich | Music | 182 | 25.63% |

| 2 | https://vk.com/id474426680 | Vadim Popov | Music | 79 | 11.13% |

| 3 | https://vk.com/chertoritsky | Sergey Chertoritsky | Music | 30 | 4.23% |

| 4 | https://vk.com/walema | Stary Ded | TV | 21 | 2.96% |

| 5 | https://vk.com/step1972 | Andrey Krivopishin | Music | 13 | 1.83% |

| 6 | https://vk.com/blogthe | The Blog | Music | 7 | 0.99% |

| 7 | https://vk.com/sergeylzar | Sergey Lazarikhin | Music | 7 | 0.99% |

| 8 | https://vk.com/s.pantsyrny | Slava Pantsyrny | Music | 6 | 0.85% |

| 9 | https://vk.com/id3788507 | Alexander Kukhtin | Music | 5 | 0.70% |

| 10 | https://vk.com/id243891102 | Lasha Ujmachuridze | Music | 4 | 0.56% |

The ten personal accounts which we discovered with the most blocked videos in Canada.

Videos Blocked in Canada Posted by Communities

This trend of the blocking of entertainment content holds in Canada for communities which posted videos that were blocked in Canada. Six of the ten blocked community video posters focused on sports, three on music, and one on cartoons. There is a focus on Russian media producer channels as well, including TV (Tele Sport, Okko Sport, and Match Premier) and radio (OMSK 103.9 FM). This content is different from blocked community posters in Russia which does include media but focused primarily on politics and current events (Belsat, Radio Svoboda, and Euradio).

| Rank | Content Poster | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share | Content Posted | Account |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | https://vk.com/telesport | 533 | 27.57% | Sports | Russian sports television “Tele Sport” |

| 2 | https://vk.com/serieavk | 313 | 16.19% | Sports | Community for Italian Soccer League “Serie A” |

| 3 | https://vk.com/silatv | 206 | 10.66% | Sports | Russian sports television “Tele Sport” |

| 4 | https://vk.com/locasta | 161 | 8.33% | Music | “Locasta” street dancing clips |

| 5 | https://vk.com/okkotennis | 119 | 6.16% | Sports | Russian TV “Okko Sport” tennis community |

| 6 | https://vk.com/okkosport | 103 | 5.33% | Sports | Russian TV sports station “Okko Sport” |

| 7 | https://vk.com/sibiromsk | 39 | 2.02% | Music | Russian radio station OMSK 103.9 FM |

| 8 | https://vk.com/2pac_one_nation | 30 | 1.55% | Music | Fan community for musician Tupac Shakur |

| 9 | https://vk.com/matchpremier | 29 | 1.50% | Sports | Russian sports television station “Match Premier” |

| 10 | https://vk.com/public207473513 | 26 | 1.35% | Cartoons | Community for “Davv Productions” |

The ten communities which we discovered with the most blocked videos in Canada.

What Content is in Blocked Videos?

Due to the high number of blocked videos which we discovered, it would be infeasible for us to watch and categorize all the content. Instead, to capture the general themes of blocked content, we randomly sampled 30 videos that were blocked in Russia and 30 videos that were blocked in Canada, watched them, and categorized them according to their content.

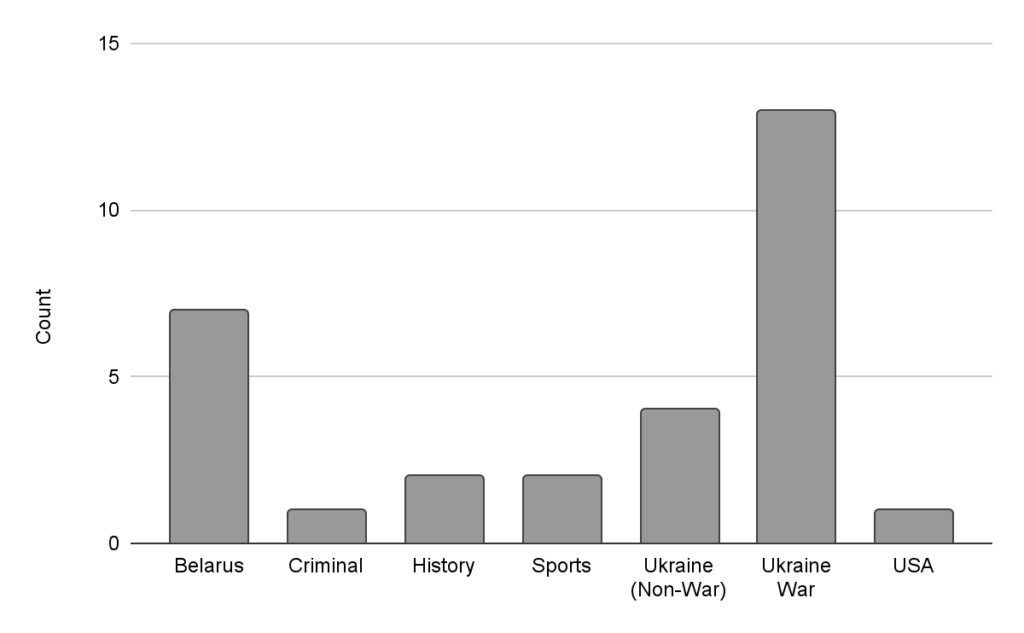

Videos Blocked in Russia

Among the 30 sampled blocked videos in Russia, we find that the largest share (43%) are videos related to the Ukraine war. The videos reviewed include war footage, demonstrations of military ordnance, interviews with service members, and talk shows discussing the war. The next largest category of blocked content concerns videos related to Belarus (26%), which include videos of protests, as well as news coverage of deaths, detentions, and tragedies. The third most observed category of blocked content is non-war Ukrainian content (13%), which includes news coverage of economic issues and nationalist marches.

| Missing in Russia | Category | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| https://vk.com/video-36069860_166138550 | Belarus | Protest around death of Belarussian in pretrial detention |

| https://vk.com/video-36069860_456240026 | Belarus | Debate between a Belarusian opposition leader Dashkevich and undercover police |

| https://vk.com/video155142793_456347462 | Belarus | Moving Iskander-2 missiles to Belarus |

| https://vk.com/video-36069860_456252718 | Belarus | Radio Svoboda coverage of detained Belarussian photographer |

| https://vk.com/video-36069860_456246093 | Belarus | TV coverage of the 1999 stampede tragedy in Minsk. |

| https://vk.com/video-22639447_456254462 | Belarus | Death of Belarusian scientist Boris Kit |

| https://vk.com/video-22639447_456264287 | Belarus | Message from Minsk Workers to Lukashenko’s Trade Union |

| https://vk.com/video-72572911_456243223 | Criminal | Ukrainian anti-corruption TV program |

| https://vk.com/video613313976_456244390 | History | Educational audio program describing Ukrainian writer and poet Borys Antonenko-Davydovych |

| https://vk.com/video-23282997_159220433 | History | Educational video about judging in Middle ages Lithuania and Ukraine |

| https://vk.com/video-18162618_456243561 | Sports | Interview with a Shakhtar Donetsk player |

| https://vk.com/video-155655277_456239927 | Sports | Ukrainian first league match between FC Hirnyk-Sport and FC Prykarpattia |

| https://vk.com/video576554975_456272785 | Ukraine (Non-War) | Interfax press conference regarding the “Mask-Show-Stop” law in pretrial detention. |

| https://vk.com/video-24262706_161238424 | Ukraine (Non-War) | Footage of UPA (Nationalist) march in Kiev |

| https://vk.com/video155142793_456308212 | Ukraine (Non-War) | Espreso TV coverage of tax evasion enforcement |

| https://vk.com/video374267542_456248883 | Ukraine (Non-War) | Coverage around spending by Speaker of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine Andriy Parubiy |

| https://vk.com/video-11019260_456247195 | Ukraine War | Ukrainian AF Russian Legion, military |

| https://vk.com/video155142793_456272568 | Ukraine War | DShK machine guns in Luhansk region competition, military |

| https://vk.com/video-93448512_456240035 | Ukraine War | War footage Ukrainian soldiers inspect destroyed Russian positions |

| https://vk.com/video715174916_456239961 | Ukraine War | Political talk show touching topics in Russia and Ukraine |

| https://vk.com/video155142793_456332156 | Ukraine War | Commentary about Ukraine and Russia |

| https://vk.com/video-5063972_456241071 | Ukraine War | Interview with soldiers in Ukrainian village of Yasinuvata |

| https://vk.com/video549895_456239793 | Ukraine War | Commentary about the Ukrainian war |

| https://vk.com/video62649817_456252177 | Ukraine War | News coverage about Ukrainian war, Bucha massacre and Kremlin actions |

| https://vk.com/video-5063972_118384509 | Ukraine War | Promotional video about Ukrainian marine unit |

| https://vk.com/video535771132_456240850 | Ukraine War | Ukrainian security service intercept of battlefield communications |

| https://vk.com/video11405356_456239226 | Ukraine War | A video with a fake “horoscope” that recommends to donate to Ukrainian army |

| https://vk.com/video-72589198_456240902 | Ukraine War | Interview with Ukrainian service member |

| https://vk.com/video-23502694_456244444 | Ukraine War | Video of Ukrainian Armed Force tanks |

| https://vk.com/video-54899733_456240014 | USA | Biden and Obama at Medal of Honor ceremony |

Categories of blocked videos in Russia from our randomly selected sample.

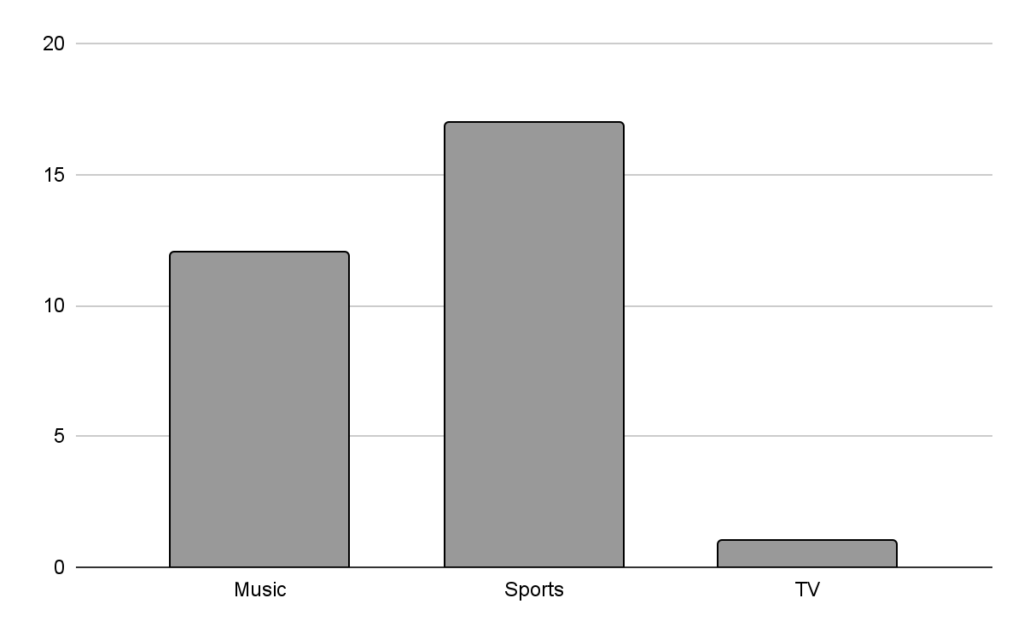

Videos Blocked in Canada

We also randomly sampled 30 videos blocked in Canada and categorized their content. In contrast to the categories blocked in Russia, which were largely related to the Ukraine war and Belarus, blocked content in Canada is more related to entertainment, specifically sports (57%), music (40%), and television programming (3%). These categories reflect that the primary motive around blocking in Canada is related to copyright enforcement. There is a complete absence of any political, news, or current events content blocked in Canada, which are categories that dominate the sample of blocked videos in Russia. These findings again indicate that the aim of censorship within Canada is very different from within Russia, with the former being focused on copyright and the latter on news, current events, and politics.

Categories of blocked videos in Canada from our randomly selected sample.

Block Messages Communicated to Users

In this section, we review the block messages that are communicated to users when they try to visit blocked content pages in Russia and Canada. We find that all content that is blocked in one region but available in another presents a message to users that explains the reason why the content is unavailable.

We discovered 336 unique messages communicated to users when they try to access blocked content in Russia. All but one message cites a Russian court order as a justification for the block. The one message observed that does not cite a Russian court order is the more general message, “This video is unavailable in your country,” which affected five videos. The remaining 335 messages are in Russian and they explain in a similar format that the video is blocked in the Russian Federation, as well as mention who requested the block, and the associated case number and date.

Despite there being over three hundred block messages which we discovered, the ten most frequently observed messages account for a large majority (77.15%) of blocked videos. The message that we observed justifying the largest number of blocked videos (33,252 videos or 35%) was requested by the General Prosecutor’s Office, citing case number “27-31-2020/Ид2145-22,” and dated February 24, 2022. Although we were unable to find the text of this court decision, this same case number was cited by the Russian communications regulator, Roskomnadzor, to block 6,037 websites, and, given its timing, we presume that it is related to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

| Rank | Message | Translated Message | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share | Cumulative Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ согласно требованию Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 24.02.2022 № 27-31-2020/Ид2145-22 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation in accordance with the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2020/Id2145-22 dated 24.02.2022 | 33,252 | 35.02% | 35.02% |

| 2 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 12.03.2015 № 27-31-2015/Ид831-15 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation on the basis of the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation from 12.03.2015 № 27-31-2015/Id831-15 | 11,943 | 12.58% | 47.60% |

| 3 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры РФ от 24.02.2022 № 27-31-2020/Ид2145-22 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2020/Id2145-22 dated 24.02.2022 | 7,776 | 8.19% | 55.79% |

| 4 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 05.04.2022 № 27-31-2022/Ид4465-22 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation on the basis of the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Id4465-22 dated 05.04.2022 | 6,373 | 6.71% | 62.51% |

| 5 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 25.04.2022 № 27-31-2022/Ид5587-22 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Id5587-22 dated 25.04.2022 | 3,013 | 3.17% | 65.68% |

| 6 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ согласно требованию Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 27.02.2022 № 27-31-2022/Треб228-22 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation in accordance with the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Treb228-22 dated 27.02.2022 | 2,928 | 3.08% | 68.76% |

| 7 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 13.08.2022 № 27-31-2022/Иф-10643-22 | This material has been blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/IF-10643-22 dated 13.08.2022 | 2,726 | 2.87% | 71.63% |

| 8 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации от 09.08.2022 № 27-31-2022/Ид11013-22 | This material has been blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Id11013-22 dated 09.08.2022 | 2,136 | 2.25% | 73.88% |

| 9 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры РФ № 27-31-2022/Ид13719-22 от 30.09.2022 | This material is blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Id13719-22 of 30.09.2022 | 1,645 | 1.73% | 75.62% |

| 10 | Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании требования Генеральной прокуратуры Российской Федерации № 27-31-2022/Треб855-22 от 30.07.2022 | This material has been blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation based on the request of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation № 27-31-2022/Treb855-22 of 30.07.2022 | 1,456 | 1.53% | 77.15% |

The ten block messages which we discovered to block the most videos in Russia.

The earliest court date mentioned in a block message was March 2, 2014, and the most recent was April 28, 2023, which was shortly before our testing period ended on May 14, 2023. This range covers a wide time period spanning 8 years and 11 months. Reviewing the cumulative distribution of the cited court case date in the messages, we see that there was an uptick in the rate of cited case dates after February 24, 2022 (see Figure 8 and Table 18), which coincides with the day that Russia began its full-scale invasion into Ukraine. Prior to this period, there was a steady and relatively consistent rate of dates mentioned in the justification. This increased pace diminished beginning late October or early November, 2022, until the end of our test period in May 2023. There also exists a gap in which no cases were cited from December 26, 2022, to January 26, 2023, although this may be explainable at least in part by the observance of the Eastern Orthodox Christmas holiday season. The reason for the brief period of diminished pace and gap is unclear. Overall the timing of these changes suggests that the ongoing conflict has dramatically increased the rate of blocking of video content for Russian users.

| Time Period | Court Orders Per Day | Comparison to Previous Period |

|---|---|---|

| March 2, 2014 – February 23, 2022 | 0.0271 | – |

| February 24, 2022 – October 31, 2022 | 0.826 | Rate increased by factor of 30.5 |

| November 1, 2022 – April 28, 2023 | 0.200 | Rate decreased by factor of 4.14 |

Comparison of rate of court orders during three time periods.

In contrast, among the videos blocked in Canada, there are no messages returned to users citing any legal justification for blocked content. The only two block messages which we observed justifying blocked videos in Canada are the more general message of “This video is unavailable in your country” (87.56%) and “Video sound unavailable” (12.44%). It is a common practice in social media moderation to restrict sound when that sound contains copyrighted music content. These messages in Canada are a stark difference from the messages seen in Russia which are more varied and which overwhelmingly cite a court order.

| Message | # of Videos Discovered Blocked | Share |

|---|---|---|

| This video is unavailable in your country | 2,288 | 87.56% |

| Video sound unavailable. | 325 | 12.44% |

The two block messages which we discovered justifying blocked videos in Canada.

Limitations

In this section, we discuss some of the limitations of our methodology. First, our methods only uncover differential censorship (i.e., censorship which is present in one region but not another). Our methods cannot uncover censorship which VK applies to all regions or countries of the world. It is likely that this report undercounts censorship and other forms of moderation carried out on the platform, as we have no visibility into deletions of content that would apply to all regions.

To illustrate this limitation, at the time of this writing, we are aware of at least seven instances of Russian-court ordered takedowns being applied outside of Russia. First is the account of Yevgeny Prigozhin, which when we browsed it on June 26, 2023, from either Canada, Ukraine, or Russia, displayed a block message citing a court order, dated June 24, 2023 (see Figure 9). On June 24, 2023, Prigozhin, the founder and leader of the Wagner mercenary group, led a mutiny and marched toward Moscow, which ended abruptly when the mercenary agreed to leave Russia for Belarus. There are six other accounts that we found blocked and that displayed this block message which are also related to Wagner Group:

- https://vk.com/obozrenie_svo

- https://vk.com/chvk.vaqner

- https://vk.com/wagner2022org

- https://vk.com/wagner_svo

- https://vk.com/orkestrwagnera

- https://vk.com/orchestrawagnera

It is unclear why VK blocked these Wagner Group-associated pages in Canada. In the block message, there is no explanation of these accounts violating any VK terms of service or safety guidelines. The only justification given is a Russian court order and a request from Roskomnadzor, which should only apply to users based in Russia. While pages related to the Wagner Group are the only examples of Russian court-ordered blocking being applied to users broadly outside of Russia that we are aware of, there may exist other instances of blocking which we have not discovered.

A second limitation of our work is that we did not perform testing from accounts which were signed in. As a consequence, we were neither able to receive search results for nor view videos which the poster of the video configured to only be visible to signed-in users. However, we do not believe this limitation to influence the direction of our findings in any meaningful way.

Another limitation of our work is that our methodology limited us to finding missing results in search queries whose results had fewer than 1,000 results. This limitation does not strictly mean that we cannot detect blocked content when it appears in the results of a query with at least 1,000 results, but it does mean that we will have to detect such content by its absence in a more narrow query. We believe that our large query sample size ameliorates this limitation, and we do not believe this limitation to skew the direction of our findings in any meaningful way.

Finally, as we tested the titles of the most popular articles on multiple language editions of Wikipedia, our methods are biased toward finding blocked videos, communities, and people related to popular topics on Wikipedia in these language editions. As an example, topics on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were popular in the Ukrainian language Wikipedia during January, February, and March 2023. As we tested the titles of the most popular articles on Ukrainian Wikipedia during this period, we incidentally tested a large number of queries related to the Ukraine war. While it is possible that this topic is popular on VK for the same reasons it is popular on the Ukrainian language Wikipedia, it is also possible that we are oversampling such videos on VK due to our large number of test queries related to this topic.

Discussion

In this section, we conclude by discussing how our findings contribute to a greater understanding of Russian social media censorship in Russia and how it compares to censorship abroad. Finally, we compare the Russian approach to social media censorship to the Chinese model of social media censorship.

Broad Keyword-Based Blocking of LGBTIQ Content

While much of the analysis we performed was on blocked videos, communities, and personal accounts, we also discovered that searches for communities and personal accounts in Russia were censored when their search queries contained keywords related to LGBTIQ content (see Table 2). We found that the use of keyword-based filtering applied exclusively to LGBTIQ terms within Russia and that it is not active in Canada or Ukraine. Moreover, it is unclear why this filtering is only applied to searches for communities and personal accounts, but not for videos. To underscore how these terms were not being censored as part of an “adult only” or safe-search filter but only being used for LGBTIQ filtering, we additionally tested the following search queries:

- pornography

- порнография

- porn

- порно

- sex

- секс

- fuck

- ебать

- блять

- трахаться

- трахать

- anal

- анальный

- bitch

- сука

- pussy

- пизда

As none of the terms above triggered keyword-based censorship of our search queries, we can conclude that the LGBTIQ-based keyword censorship is not part of a larger safe-search feature but rather one meant to target solely LGBTIQ-related search queries.

It is unclear why keyword-based filtering is only used to censor LGBTIQ search queries and not queries for content critical of Putin, the invasion of Ukraine, or other content found blocked elsewhere on VK. Keyword-based blocking is a particularly blunt tool. On one hand, it is overly broad, capturing content that may not have been intended. For example, we found that many anti-LGBTIQ groups existed on VK, and thus the blocking of LGBTIQ-related searches prevented users from discovering pro- and anti-LGBTIQ groups alike. On the other hand, keyword-based blocking is simultaneously narrow. As one example, we found that “LGBT” and “LGBTQ” were blocked but not other variants such as “LGBTQIA”. As another, although “gay” was censored, “gays” was not. Some terms were blocked in both Cyrillic and Roman characters (e.g., “Геи” and “gay”) while others only in Cyrillic but not in Roman (e.g., “Фембой” but not “femboy”). These inconsistencies give the impression that the list of blocked terms used by VK was arbitrarily created. Finally, as keyword-based filtering only applies to searches, users can still access communities and personal accounts whose names contain blocked keywords by searching for other keywords in their names or by typing the URLs to their pages directly.

Given that keyword-based blocking is simultaneously both too broad and too narrow, as well as ineffective, it is unclear why it is applied only to LGBTIQ content, much less any content at all. One possibility is that, because the anti-LGBT “propaganda” laws (including the federal law “for the Purpose of Protecting Children from Information Advocating a Denial of Traditional Family Values”) are vague concerning what constitutes “LGBT propaganda,” this type of filtering is intended to be very visible to users, although it is not actually effective at censoring content. In this sense, this filtering may be acting as a sort of “compliance checkbox” to attempt to demonstrate compliance with Russian law.

Consistent Legal Justification

We found that VK attributed every blocked community or person in Russia to a court decision and that every blocked video in Russia was attributable to a blocked community or person. Altogether, there were 336 different VK block messages that cited 303 unique legal case numbers. In some instances, we were able to find the text of the court decision ordering the blocking of the communities or personal accounts and retrieve the law cited to justify the ordering of the blocking. More study is needed to systematically analyze the court cases and laws justifying VK’s blocking decisions and to determine both whether VK cites appropriate court decisions to justify its blocking and whether those court decisions cite appropriate laws to justify their blocking orders. It seems that, in many cases, the necessary information may be available to perform such an analysis. At this time, we will merely call attention to one block message which is notable because a press release was also cited:

“Этот материал заблокирован на территории РФ на основании решения суда/уполномоченного федерального органа исполнительной власти (Металлургический районный суд г. Челябинска – Челябинская область) от 11.12.2019 № 2а-3052/2019 Комментарий ВКонтакте: vk.com/press/blocking-public38905640”

In English:

[This material was blocked on the territory of the Russian Federation on the basis of the decision of the court / authorized federal executive body (Metallurgichesky District Court of Chelyabinsk – Chelyabinsk Region) dated December 11, 2019 No. 2a-3052/2019 Comment VKontakte: vk.com/press/blocking-public38905640]

In the linked March 2021 press release, VK notes Russia’s increasingly tightening regulations of social media networks and legal obligations to implement proactive censorship measures in justifying the blocking of the “Альянс гетеросексуалов и ЛГБТ за равноправие” [Alliance of Heterosexuals and LGBT for Equality] VK community.

Gaps in Blocking Transparency

While VK consistently attributed blocking in Russia to court orders, VK’s approach of blocking users, and then transitively all of their videos, rather than blocking specific videos themselves, still lacks transparency on multiple levels. Although VK consistently provides a legal justification for why a community or personal account is blocked in Russia, when viewing a blocked video it is not clear who the poster was, and, even if the blocked poster is known, it is not clear to other VK users which video or other content from that user may be responsible for their blocking. This problem is exacerbated as VK’s blocking has the effect of capturing all past and future posted videos of the blocked community or personal account. Thus, VK’s approach has a tendency to over-block, as a community or personal account may have multiple interests and post content on a variety of topics, including benign ones that are unrelated to the original justification of a block. Reviewing some of the court orders which VK cited in justifying account blocking, we found that the orders had no associated time period. Thus, the blocks may be applied in perpetuity, exacerbating this over-blocking. Further, it is not clear if VK notifies a poster that their content is being blocked in Russia. Thus, VK users may be unaware that all of their content is unavailable to users in Russia, especially if they are using VK from a region other than Russia.

Inconsistent Copyright Enforcement

We found that copyrighted entertainment content was often blocked in Canada including TV, sports, and music, while current events was the type of content that was blocked the most in Russia, mainly those dealing with the Ukraine war and Belarus. Copyrighted content was thus largely accessible in Russia even when it was blocked in Canada. Although in this report we did not systematically compare Ukraine and Canada for differential blocking, we generally observed that the same copyrighted content unavailable in Canada was accessible in Ukraine. This observation suggests that VK approaches moderation around copyright on a geographical basis, rather than using a method which distinguishes Russia from all other countries. Based on our analysis, VK’s approach to copyright moderation is far more lax and permissive in Russia and Ukraine than in Canada. That is, VK users in Canada have more content restricted based on a copyright justification, compared to users in Russia and Ukraine. We also found, despite this uneven application of copyright enforcement, that pirated content is widespread on the platform. This finding is especially true for ebooks and music content, which are widely available on VK.

This differential treatment of users by region is also revealed in other manners, such as in VK’s privacy policy, which has different data retention policies for Russian users versus users outside of Russia. For example, according to those policies, VK “store[s] Russian users’ messages for six months and other data for a year (in accordance with paragraph 3, Article 10.1 of Federal Law ‘On Information, Information Technologies, and Information Protection).”

Comparison to Chinese Social Media Censorship

China’s social media information control system is decentralized and characterized by “intermediary liability,” or what China refers to as “self-discipline,” allowing the Chinese government to push responsibility for information control to the private sector. Internet operators which are deemed to have failed to have adequately implemented information controls are liable to receive fines, have their business licenses revoked, or be the recipient of other adverse actions. These companies are largely left to decide on their own regarding what to proactively censor on their platforms, attempting to balance the expectations of their users with appeasing the Chinese government. In China, block messages are often not displayed by Chinese platforms and therefore users have no way of knowing the legal justification for the blocked content. However, in Russia, VK ultimately attributed the blocking of each video, community, or person to whichever court case ordered the blocking of that content. In some cases, we were able to find the text of the court case and retrieve the laws cited in justifying the takedown request. While much may be lacking in terms of due process in Russia’s court-ordered blocking approach, this system is still more transparent than in China, where blocking decisions are more proactively done by the private sector, with blocking decisions being left largely to the discretion of Internet operators.