Key Findings

- In August 2019 a wave of websites and social media channels, called “HKLEAKS,”2 began “doxxing” the identities and personal information of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong. While the creators of these sites and channels claimed that HKLEAKS was the product of local volunteer communities, several indicators suggest a coordinated information operation conducted by professional actors in alignment with Chinese state interests.

- The core campaign employed strong operational security measures, going to great lengths, and using significant skills and resources, to hide the identity of its actors.

- Active maintenance of the operation stopped by mid 2021, once most of the campaign’s targets had been arrested or exiled, with almost all the linked assets ceasing their activity or changing their focus. This, combined with other suspicious signals we have detected, is characteristic of an artificial campaign and not of an organic, community-driven effort, which typically trails off gradually.

- This operation is a clear example of a multi-faceted approach to information operations, that not only disseminates content designed to influence opinions, but also uses intimidation tactics — such as doxxing — intended to suppress the targets’ activities.

- While a conclusive attribution cannot be attained at this stage, we identify circumstantial evidence that suggests the campaign operators held links to mainland China.

Summary

In August 2019, at the height of the Anti-Extradition Bill protests that rocked Hong Kong, a series of websites branded “HKLEAKS” began surfacing on the web. Claiming to be run by anonymous citizens, they systematically exposed (“doxxed”) the personal identifiable information of protesters, journalists, and other individuals perceived as affiliated with the protest movement. A number of analyses [1, 2, 3, and more] over the subsequent months and years, as well as individual observers, surfaced several peculiar features of this operation, from the dodgy Russian-based hosting of its web domains, to the synergy with Chinese state media, to the suspicious sourcing of the data used for the doxxing.

In this report:

- We conduct a forensic analysis of the entire identifiable digital footprint of the HKLEAKS campaign

- We map:

- its confirmed assets;

- its tactics;

- its connections to a broader supporting network; and

- the discrepancies between its operators’ claims and the available evidence

- We focus our analysis on the research question: what is the real nature of the HKLEAKS campaign?

Finally, we surface new circumstantial evidence tilting our conclusions towards the hypothesis that HKLEAKS had a direct connection to mainland China, despite claims it was conducted by “anonymous netizens” based in Hong Kong.

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- A context section summarizing the historical context for the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests

- An introduction to the HKLEAKS campaign

- The main analysis, revolving around our overarching research question on the actual nature of the HKLEAKS campaign. This section is broken down into:

- The research question

- An analysis of the competing hypotheses we examined against the research question

- Four analytical assessments [1, 2, 3, 4], and the further breakdown of the evidence supporting each of them

- Conclusions

- Finally, an extensive Appendix containing content samples, technical indicators, and other evidence we have collected over the course of our research

Context

Anti-Extradition Bill Protests (2019-2020)

In February 2019, the Hong Kong government proposed a bill regarding extradition, which would establish a mechanism for transfers of fugitives to mainland China, Taiwan, and Macau. The government claimed the proposal was necessary as a result of a murder case which took place in Taiwan, where the suspect returned to Hong Kong and could not be extradited to Taiwan due to a lack of extradition treaties. The proposed bill was controversial because it also facilitated extradition to mainland China, which has a fundamentally different judicial system than Hong Kong. Critics claimed that it would endanger freedom of speech and civil liberties enjoyed in Hong Kong as people could be subject to arbitrary detention and unfair trials.

The business community, legal sector, human rights groups, and opposition parties expressed concerns for the proposed bill. The first protest occurred on March 31, 2019, followed by several more in April and May. Despite a massive protest on June 9, where some estimates put the attendance at over a million people, the government announced it would continue the second reading of the bill on June 12, 2019 as originally planned. On June 12, protesters successfully stalled the second reading of the bill by gathering outside the government headquarters. The police, however, used tear gas, rubber bullets and bean bag rounds to disperse the protesters and were widely condemned for the use of excessive force. After June 12, the focus of the protests expanded beyond the extradition bill to include holding the police accountable for excess brutality and use of force. With public opinion increasing against her, Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced she would “suspend” the second reading of the bill on June 15. Concerned that this was merely a temporary “suspension”, and not a full withdrawal of the bill as demanded, another protest occurred the next day, on June 16, with the participation of over two million people.

With the bill still not fully withdrawn, the protests continued to escalate, taking place during the annual pro-democracy march on July 1, 2019, where protesters took over the Legislative Council by breaking through glass doors. In July and August, there were almost daily occurrences of protests, and clashes with the police who often used excessive force to repress the protests.

On September 4, Lam announced the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill, but at this point the goals of the protests had broadened beyond the withdrawal of the bill, in large part because of the government’s tactics to repress the protests, and centered around these five demands:

- Withdrawal of the extradition bill

- Retraction of the “riot” characterisation for protests

- Release and exoneration of arrested protesters

- Establishment of an independent commission of inquiry into police conduct and use of force

- The resignation of Carrie Lam and the implementation of universal suffrage for Legislative and Chief Executive elections

The protests continued, even when the government invoked the Emergency Regulations Ordinance to ban the use of face masks in public gatherings in order to make it difficult for protesters to protect their identity. Student protests and sieges of universities occurred in November. The District Council elections, an election for the local councils of the 18 districts in Hong Kong, and the only election in Hong Kong where every citizen gets to vote, and thus widely seen as a referendum on the government, had record high voter turnouts, and saw the landslide victory of the pro-democracy camp.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the protests ceased in early 2020. In May 2020, Beijing announced plans for a national security law for Hong Kong, entirely bypassing the Hong Kong government and the public, even though this was supposed to be legislated by the Hong Kong government. The People’s Republic of China’s National People’s Congress Beijing promulgated the national security law for Hong Kong on June 30, 2020. As a result of the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and the national security law, protests died down in 2020.

Violent Incidents and Repression

Reports of police violence and excessive use of force were widespread throughout the protests. Experts claimed that the police had violated their own guidelines, and even international human rights laws and standards, in many incidents during the protests. Verifiable footage shows indiscriminate use of crowd control weapons, disregard for public safety, and mistreatment of detainees.

- A particularly important moment took place on July 21, 2019 in Yuen Long, in the New Territories. The police failed to stop likely triad members from indiscriminately hitting protesters, even after repeated calls for help.

- Despite receiving over 24,000 emergency calls that night regarding the incident, the police took more than 30 minutes and arrived immediately following the departure of the triad members

- People were outraged at the incident not only as a result of the late arrival of the police, but also due to the shutdown of nearby police stations and the refusal of police to intervene when bystanders approached for help

- This particular incident resulted in insinuations in the protest movement, as well as in international observers, that the Hong Kong authorities, acting as a proxy for the Chinese government, would employ third-party actors (the triads, in this case) to maintain a thin veil of plausible deniability in the repression effort3

- Another key moment occurred on August 31, 2019, when violence further escalated and this time the police themselves indiscriminately attacked passengers and protesters in a subway station.

- The Hong Kong authorities’ refusal to take accountability following these incidents generated considerable concern and dissatisfaction not only within the protest movement, but also the broader international community.

- In a rare moment, then Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung initially apologized for the delayed police response on July 21 in Yuen Long and said that “the police’s handling fell short”, but then backtracked after pressure from police unions, claiming that the police had “fulfilled its duties in maintaining social order under enormous stress at this difficult time”

- Chief Executive Carrie Lam continued to outright reject the call for an independent commission of inquiry into police conduct and use of force, one of the five demands of protesters

- As of today, no police officers are known to have been disciplined or prosecuted for excessive force during the protests

Doxxing of Police Officers by Protesters

Despite a large number of filed complaints, in practice, the police have not been held accountable for their role in the violence of the 2019 protests. Starting in June 2019, police officers stopped wearing warrant cards on their uniforms and refused to produce them when requested, making it impossible to identify them individually. Some also began hiding their faces by applying a one-way-mirror privacy film to their helmets’ visors. In contrast, in December 2019 the government invoked an emergency law to ban the use of face masks by protesters in public gatherings. By December 2019, 1400 individual complaints against police officers had been made; however, none had been formally prosecuted by the authorities. It is in this context that some protesters resorted to doxxing police officers.

In this report we define doxxing as the search for and the publication of an individual’s personal data on the Internet with malicious intent.4 In this particular case, protesters sought to expose the identity of individual police officers who were identified as responsible for unchecked abuses.

The doxxing of police officers mainly occurred on the messaging app Telegram, on LIHKG, a discussion forum that is often referred to as “the Hong Kong version of Reddit”, and via dedicated websites such as hkchronicles[.]com. The personal information revealed included (but at times was not limited to) the officers’ phone numbers, social media accounts, addresses, dates of birth, and family members. The Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data said that complaints filed to its office increased between June and September 2019, and that 70% of cases involved police officers. It is important to note that many protesters who have been doxxed likely did not file a complaint, given that the police would have been responsible for the investigation and prosecution.

As a countermeasure, the Hong Kong High Court granted two injunctions in 2019 and 2020 to specifically protect police, judicial officers and their families from being doxxed. Finally, in September 2021 Hong Kong’s legislature passed the bill introducing anti-doxxing legislation. Applying hefty fines of up to HK$1 million, and up five years in prison, the new law gave significant additional powers to the Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (PCPD), which included, for example, the ability to block websites, apply for warrants to enter and search premises and seize materials for investigation, but also provide warrantless access to seized electronic devices. Critics immediately highlighted how this bill was designed to prevent the doxxing of police officers, leaving the protesters’ side effectively unprotected, if not more vulnerable, given the apparent lack of interest by the authorities in prosecuting doxxing when committed by pro-Beijing groups; and tech companies had warned how its implementation could force them to abandon their operations in the Special Administrative Region (SAR).

HKLeaks

In August 2019, a new website called “HKLEAKS” (with an initial domain at hkleaks[.]org) caught the public’s attention as it anonymously “doxxed” alleged protesters, exposing their Personal Identifiable Information (PII) via a series of doxxing cards. These were essentially small graphic boxes, prominently displaying the target’s picture (when available), accompanied by textual information such as the person’s date of birth, home address, social media profiles, phone numbers, and often more.

The website was almost immediately denounced by the protest movement and its supporting online community. As the website quickly went down — to date the cause remains unclear — it was immediately replaced with a stream of new websites hosted on domains that all used the same “hkleaks” naming convention, as we will illustrate in detail later in this report.

The PCPD of Hong Kong responded to a media inquiry filed in regards to them on September 17, 2019. In its response, the PCPD acknowledged that the website (in its different domain permutations) “clearly violated Article 64 of the ‘Privacy Ordinance’, ‘Disclosure of personal data obtained without the consent of the data user is an offense’,” and referred the case to the police for the opening of a criminal investigation, “including investigating the information of the operator of the website involved and considering prosecuting.” However, the PCPD had already previously admitted that “the domain name of the website involved in the “documentation” is registered outside Hong Kong (namely Russia), and the server of the website is not located in Hong Kong. The Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (“Privacy Ordinance”) has no extraterritorial jurisdiction. Therefore, the PCPD does not have the legal power to compel relevant organizations outside the territory (including companies that assign domain names and companies that provide servers) to provide information about the website operator”.

Analysis

Research Question

As successive versions of the website were rapidly launched, and most were quickly removed, what remained consistent was the claim by their operators of being a grassroots organization, composed by Hong Kong citizens concerned and exhausted with the protests.

We therefore considered the research question: What was the nature of the HKLEAKS campaign?

The following are the four hypotheses reviewed against this question.

- HKLEAKS was an authentic grassroots movement as claimed by its operators. It was generated by Hong Kong residents in response to street protests that had heavily disrupted the city’s life. It was not directed or sponsored by, and/or coordinated with governments or other organizations.

- HKLEAKS was an artificial campaign created and conducted by a private or governmental actor in Hong Kong (with some possible engagement by organic, sympathetic online communities). It supported pro-Beijing political lines, but was run by a local entity independently from any direct sponsorship or coordination from the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

- HKLEAKS was an artificial campaign created and conducted by the Chinese government, or an organization on its behalf (with some possible engagement by organic, sympathetic online communities). While the latter may also include an organization or governmental entity in Hong Kong, the difference between this hypothesis and #2 is a direct responsibility of the PRC on the generation and conduction of the operation.

- HKLEAKS was an artificial campaign created and conducted by another nation-state or their proxies. Motives could also include blaming China for it, or building a false or exaggerated narrative on its will to squash any dissent in Hong Kong, both online and offline.

Analysis Of Competing Hypotheses (ACH)

We reviewed the collected evidence utilizing a structured analytical method — a standard matrix for the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) — designed to show the degree of consistency or inconsistency of a piece of evidence against alternative research hypotheses.

Legend:

- ✅ = consistent with [hypothesis]

- ❌ = inconsistent with [hypothesis]

- 🟰 = could be consistent or inconsistent with [hypothesis]

The evidence is presented in the first column, while the competing hypotheses are represented in columns 2-5.

The analysis led us to the following conclusions:

H1. GRASSROOTS MOVEMENT, COMPLETELY ORGANIC

Low-Likelihood Scenario

- All the technical and behavioral signatures of the campaign point away from this hypothesis.

- The only piece of evidence consistent with it does not exclusively match an organic effort, but would rather support any of the four hypotheses.

H2. INORGANIC, INDEPENDENTLY RUN BY PRIVATE ENTITY OR GOVERNMENT AUTHORITIES IN HK

Likely Scenario

- The majority of the evidence that we have identified is consistent with the hypothesis of a state-backed influence operation.

- The similarities in layout and language between HKLEAKS and the anonymous bounty campaign HongKongMob, which in turn closely resembled the example overtly set by the Hong Kong-based 803 Fund, could indicate an HK-based (artificial) campaign.

- It is possible that the campaign also benefited from some degree of organic engagement by sympathetic online communities.

- Some doxxing used privileged information, only available to the Hong Kong and/or Chinese authorities.

H3. INORGANIC, CHINA STATE-SPONSORED

Most Likely Scenario

- The majority of the evidence that we have identified is consistent with the hypothesis of a state-backed influence operation.

- The timing coincidence between the removal of a Chinese state-sponsored IO by Twitter in July/August 2019, and the start of the HKLEAKS campaign, is an indicator tilting the analysis towards HKLEAKS being backed by the Chinese government.

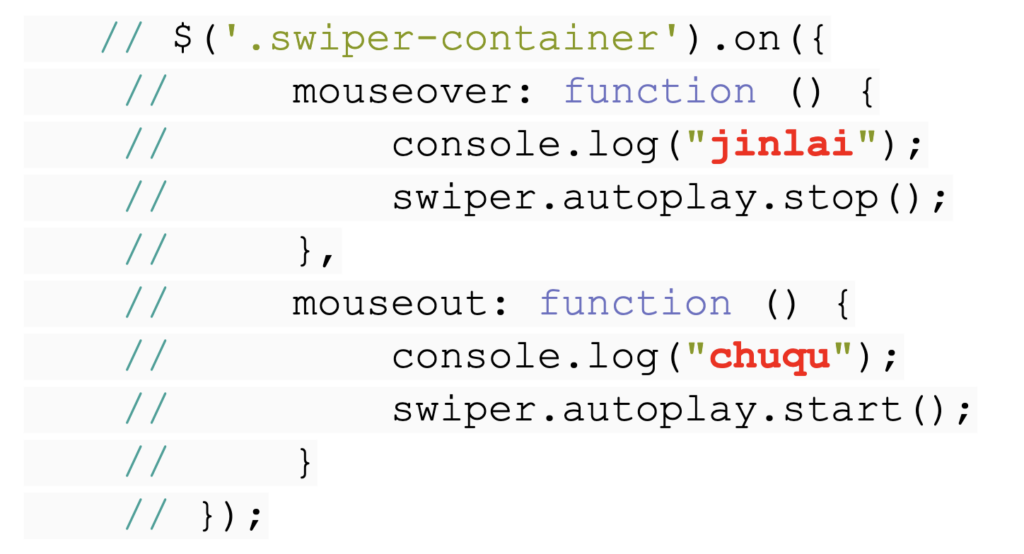

- Javascript code used by HKLEAKS contained Mandarin words and acronyms in Hanyu Pinyin spelling, typical of mainland China.

- Some doxxing used privileged information, only available to the Hong Kong and/or Chinese authorities.

- It is possible that the campaign also benefited from some degree of organic engagement by sympathetic online communities.

H4. INORGANIC, OTHER STATE-SPONSORED

Low-Likelihood Scenario

- Consistent with the technical signatures of the HKLEAKS campaign.

- However, no piece of evidence specifically supports this hypothesis against the others: in other words, all the evidence potentially in support of HKLEAKS being a deceptive campaign run by another nation-state could also be consistent with one or more of the other hypotheses.

- Additionally, multiple pieces of evidence point against this scenario.

In the following sections, we break down the evidence, and outline the analysis leading us to the above conclusions.

Assessment #1: HKLEAKS was an Artificial Campaign

Designed to be Unattributable

HKLEAKS was a carefully crafted campaign, designed to avoid attribution.

A total of at least 25 web domains were used, all mirroring identical content. They were created and published in a relatively rapid sequence (see the related section). For a few additional domains, despite their use of the same HKLEAKS naming convention, we could not conclusively confirm they were used for the doxxing operation.

The first HKLEAKS domain to be registered as part of the operation, in mid August 2019, was hkleaks[.]org. Early observers quickly noticed that its setup followed strict operational security guidelines meaning the owners of the domain went to great lengths to hide their own identity and affiliations and clearly possessed security and privacy skills. This remained a consistent feature throughout the entire operation:

- All domain registrations but four were strictly privacy-protected, therefore anonymizing the information of their registrants

- For the four domain registrations with some visible personal data, we assess that the information provided was most likely inauthentic

- Three domains contained Japanese identifiers5 that do not appear to correspond to real individuals or organizations

- One used a Hong Kong persona with a placeholder name (San ChiNan) akin to “John Doe” in English

- All four had anonymous email addresses associated with the registrations.

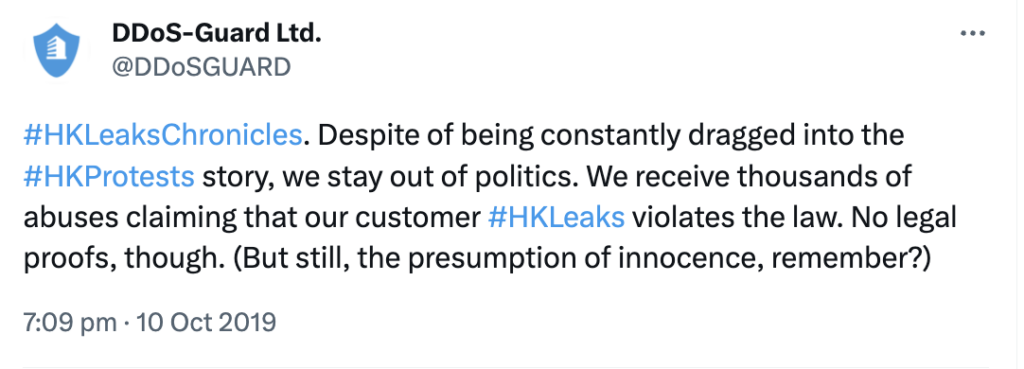

- Furthermore, the majority of the HKLEAKS domains were registered through DDoS-Guard, a dodgy Russian-based registrar notorious for offering protection to harmful actors

- DDoS-Guard, facing substantial pressure to block the doxxing websites, refused to do so, addressing the requests in a short series of dismissive tweets in 2019 [1] [2] [3] [4].

- As mentioned above, the PCPD of Hong Kong, responding to a media inquiry in September 2019, acknowledged that the jurisdiction in which the website had been registered was the main obstacle to its enforcement of the Personal Data Privacy Ordinance, which hkleaks[.]org “clearly violated”. The PCPD opinion was not legally binding, but it did show that DDoS-Guard’s arguments, one month later, about a “presumption of innocence” had been made in bad faith.

- The only HKLEAKS domain that remains visible in 2023 — hkleaks[.]pk — had its registration data wiped out. It currently only shows the Domain Name Server (DNS) it points to — owned by DDoS-Guard — but nothing on the registrant individual or organization

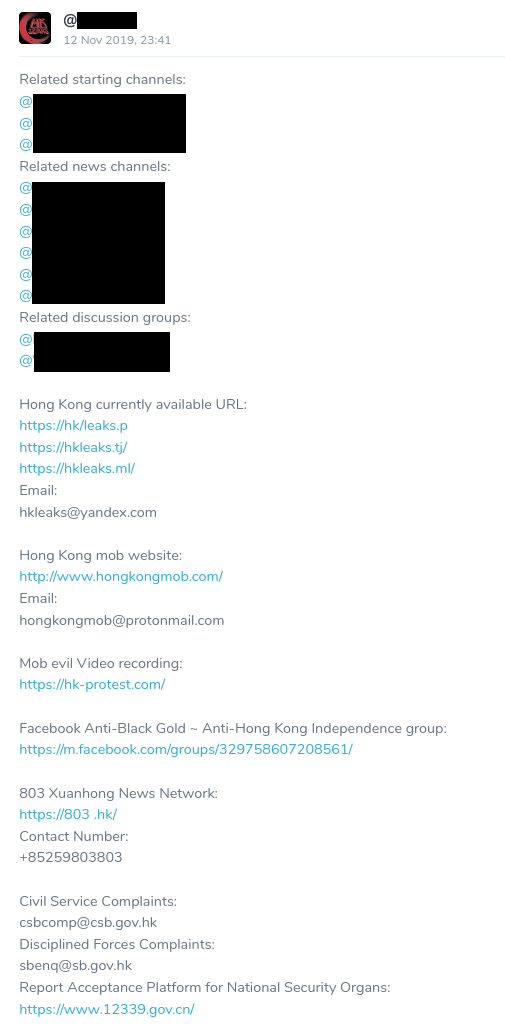

- Additionally, the only two email addresses published as contacts by HKLEAKS (hkleaks@yandex[.]com and hkleaker@yandex[.]com) were both registered on a Russian free email provider, Yandex. This placed them once again outside of the Hong Kong law enforcement jurisdiction.

Finally, we have reviewed the HTML structure of the websites associated with the HKLEAKS domains, and systematically searched for identifiers in their source code. We have conducted the analysis using the following techniques:

- Crawled all the available websites’ versions (both the only surviving live website, hkleaks[.]pk, and the archived versions of the other domains available on the Wayback Machine) to extract identifiers, and manually review them

- Sifted through the social media dissemination of its content – also to extract identifiers, and manually review them

- Analyzed the HTML code structure of the websites

As a result:

- We could not locate any identifiers within any of the websites’ code

- We can assess that even in their most developed versions, the websites’ structure was barebone, with the probable intention to reveal as little information as possible beyond what was intended by its operators. It included:

- a homepage with the mentioned header and a sample of the doxxing cards;

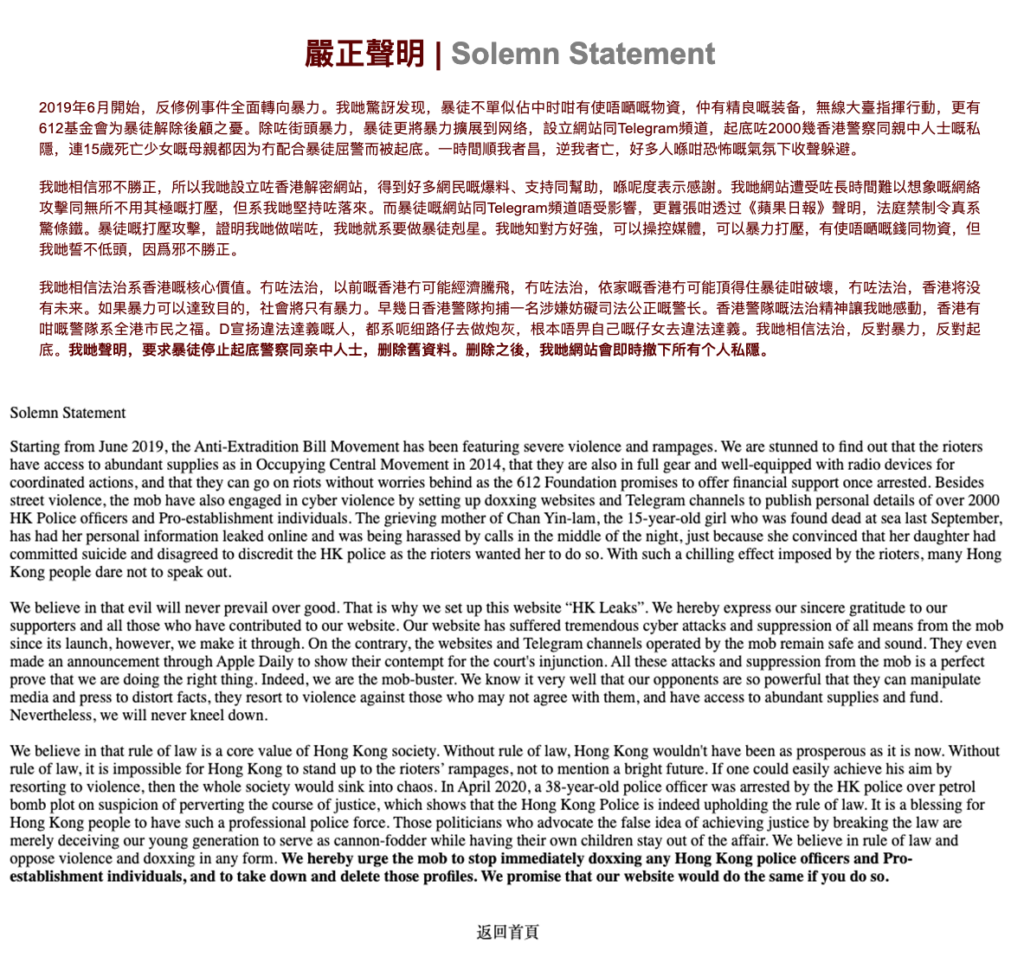

- a splash page with a “Solemn Statement” (a manifesto concerning the purpose of the website, available in both Chinese and English);

- a section with the full list of individuals being doxxed; and

- a search module.

- The websites’ source code also did not include any distinctive elements allowing the identification of an off-the-shelf template being used.

The online footprint of HKLEAKS was therefore conceived by operators with sufficient planning and technical expertise to avoid attribution.

Persistent

Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs) — “prolonged, aimed attack[s] on a specific target with the intention to compromise their system and gain information from or about that target” — include one characteristic that is pertinent in this investigation: persistence. This attribute denotes the actor’s ability and willingness to be resilient to change, and to conduct its attacks long-term in order to pursue a predetermined objective.

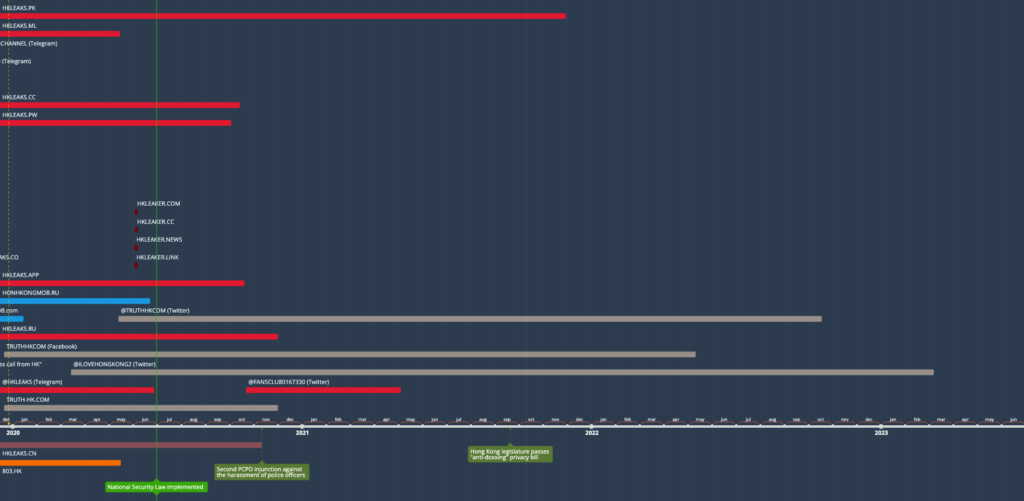

The whole HKLEAKS campaign was actively maintained for approximately two years, from August 2019 to May 2021, when a Twitter account claiming to represent the network and promoting the doxxing content, @FansClu80167330, ceased its activity. In this span of time, HKLEAKS:

- doxxed approximately 2,800 individuals;

- regularly updated its websites’ content;

- hopped between at least 25 different web domains, moving through two different layout types, and eventually morphing the website’s structure to also incorporate pro-Beijing political news and commentary;

- created, managed, and updated at least one Twitter account promoting the websites’ doxxing content; and

- created, managed, and updated at least 24 Telegram channels promoting the websites’ doxxing content,

- Note: we retain the list of identified Telegram channels, as well as refraining from showing the related doxxing content, due to the particularly private nature of most of the information therein contained.

Additionally, it is likely that HKLEAKS disseminated and promoted doxxing content through a number of other platforms, where the network’s presence did not use the same naming convention, but rather personal accounts purported to belong to real individuals. Examples of such platforms include the instant messaging app WeChat; and the microblogging platform Weibo. It was also observed that social media platforms such as Twitter (and, potentially, Facebook and Instagram) had started blocking links to the HKLEAKS domains early on during the campaign. This likely limited the spread of the campaign through such platforms.

Finally, it should be highlighted that the most recently created domain, hkleaks[.]pk, is still online to this day, albeit not updated since 2021.

In summary, HKLEAKS demonstrated the following features:

- The ability to branch out across multiple platforms to ensure the campaign’s resilience against alleged attacks aimed at taking their websites offline.

- The capability and willingness to maintain a consistent flow of content for close to two full years.

- Just using the only still visible HKLEAKS domain (hkleaks[.]pk) as an example, by reviewing its 807 captures (as of May 2023) in the Wayback Machine we can observe regular updates of both its layout, and content.

- The ability to preserve complete anonymity (akin to the stealthy behavior of APTs) throughout the campaign — as seen in the previous section.

While the operators’ behavior and methods are certainly different from that of an APT, the campaign’s persistence denotes the attributes of activity that is externally driven, has a strategic objective, and is prepared for resilience against rapidly changing and adverse conditions.

Similar to Other Fake Grassroots Campaigns

The claim by HKLEAKS of being a grassroots campaign, created by a group of Hong Kong citizens who “believe […] that rule of law is a core value of Hong Kong society” — as they declare in their “Solemn Statement” manifesto, and as opposed to the allegedly illegal behavior of the protesters — is also a known tactic historically used by inorganic campaigns.

In combination with the other characteristics presented in this report, we assess that it was likely that the HKLEAKS campaign was falsely labeled a grassroots campaign.

Multiple examples of such behavior have been surfaced by research on information operations over recent years. We present three examples of this scenario below.

- In December 2019 — coincidentally, in concomitance with the peak of the HKLEAKS activity — Twitter announced the removal of approximately 6,000 profiles engaging in an information operation attributed to a private company based in Saudi Arabia. A parallel analysis of this network conducted by the Stanford Internet Observatory assessed that “the tweets [produced by the network] were designed to look like the expressions of real people […]. Social media marketing tactics are frequently misused for influence operations and this behavior looks like it was trying to mimic grassroots enthusiasm (sometimes called “astroturfing”).”

- In August 2022, Meta reported on the removal of more than 1,000 Instagram accounts, as well as 45 Facebook ones, “which targeted global public discourse about the war in Ukraine.” The company’s analysts assessed that the operation “appeared to be a poorly executed attempt, publicly coordinated via a Telegram channel, to create a perception of grassroots online support for Russia’s invasion”.

- In February 2023, again Meta announced the removal of a “coordinated inauthentic behavior” (CIB, the protocol that the company utilizes to define covert information operations) network based in Serbia. The operation “targeted domestic audiences across many internet services, including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, in addition to local news media to create a perception of widespread and authentic grassroots support for Serbian President Aleksander Vučić and the Serbian Progressive party.”

A common feature of all these operations is to mask the actions directed by an organization behind the facade of a grassroots community movement. They disguised their actual operators, as well as their likely sponsors, behind inauthentic profiles purportedly representing genuine supporters of the causes promoted by the operations.

Assessment #2: HKLEAKS had Plausible Links to Mainland China

Javascript Code

We identified clues pointing to HKLEAKS potentially originating in mainland China.

An analysis of the Javascript files available on the HKLEAKS websites revealed clues that their developers likely spoke Mandarin. This is significant because Mandarin is the official language (and the one predominantly used) in mainland China and Taiwan, as opposed to Cantonese, used in Hong Kong and Macau.

Specifically, two terms in commented-out code within the file gdlb.js (“jinlai”, for 進來 , to enter; and “chuqu”, 出去, to leave) are pinyin (the standard system of romanized spelling for transliterating the Chinese language, adopted officially by the People’s Republic of China in 1979) of Mandarin. The file’s name, “gdlb”, is likely to be an acronym for “gun dong lun bo“, which in turn is pinyin for 滾動輪播 , “scroll and slideshow”.

Also, the preferred language used by web developers in Hong Kong would tend to be English, as part of the known code switching between that language and Cantonese.

To further narrow down the attribution of this piece of code to a likely mainland Chinese developer, we need to consider that the specific transliteration system utilized here is Hanyu Pinyin, which is only widely used in mainland China, but not in Taiwan, where Mandarin is used, but in Bopomofo spelling. Note: In Taiwan, Hanyu Pinyin is used mostly for transliterating proper nouns only. Most people do not learn Hanyu Pinyin and instead use Bopomofo to spell. In mainland China, Hanyu Pinyin is used to both spell and transliterate.

Launch Of HKLEAKS Follows Shortly After Twitter’s Removal of a Disinformation Campaign from Mainland China

An information operation targeting the Hong Kong protests (as well as touching other topics of interest to Beijing) and attributed to the Chinese government was removed by Twitter in late July 2019. Its removal coincided with the launch of HKLEAKS. This is likely to indicate that the latter represented an increase in the diversity of the tactics to continue pursuing the attack towards the Hong Kong protest movement, while avoiding enforcement by the host platforms.

On August 19, 2019, the Twitter Safety team published a blog post detailing the removal of more than 900 accounts that the company conclusively determined to be “originating from within the People’s Republic of China (PRC).” The accounts in question were directly connected to a much broader set of approximately 200,000 spam profiles that were preemptively disabled by Twitter before they could engage in activity through the company’s platform. These 900 were those which managed to artificially disseminate content “deliberately and specifically attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong, including undermining the legitimacy and political positions of the protest movement on the ground.”

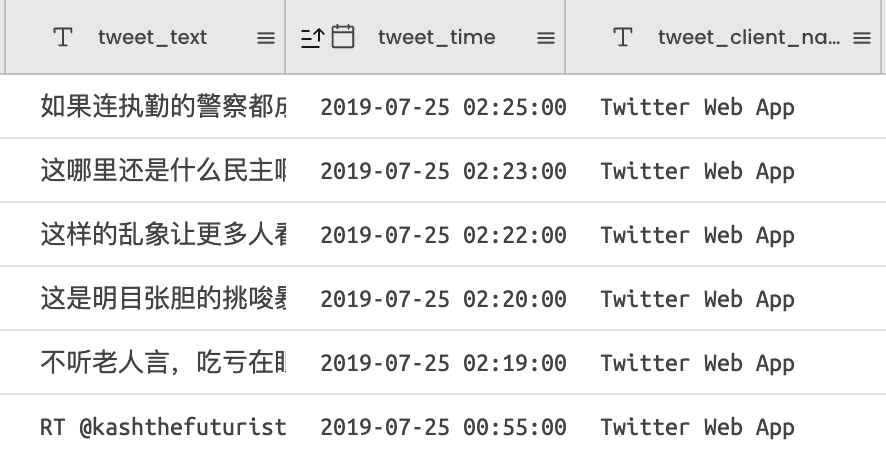

The two datasets released by Twitter via the company’s Twitter Moderation Research Consortium, in conjunction with the blog post, shed a light on the operation in question. A preliminary analysis conducted by the International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) concluded that “the information operation targeted at the protests appears to have been a relatively small and hastily assembled operation rather than a sophisticated information campaign planned well in advance.” However, “research has also found that the accounts included in the information operation identified by Twitter were active in earlier information operations targeting political opponents of the Chinese government.”

We do not know for certain on what date Twitter had disabled the accounts, but a review of the timestamps associated with the two sets made available by Twitter shows that the last available tweets were posted on July 25, 2019, which is likely to be the date that the block was applied.

The first ever confirmed HKLEAKS domain, hkleaks[.]org, was registered on August 16, 2019 — approximately three weeks after the Twitter takedown, and three days before its announcement.

This timeline suggests that the domain registration was likely made in response to the Twitter campaign takedown.

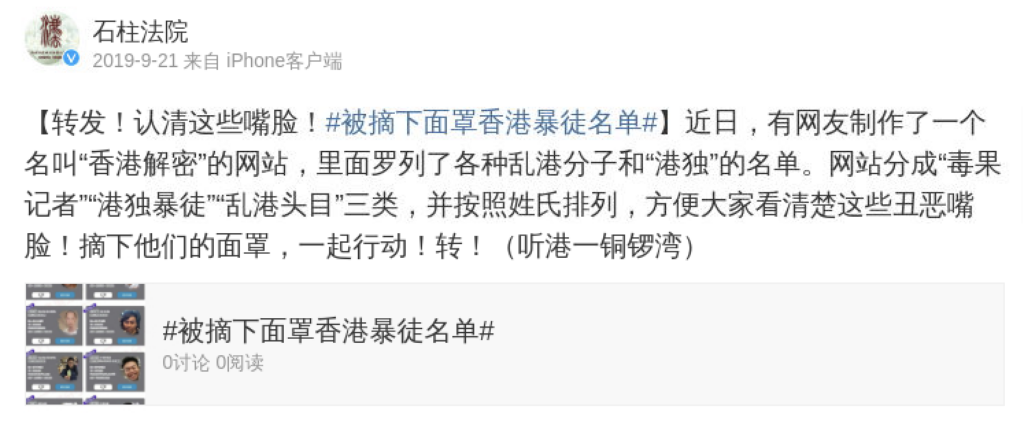

Beijing’s Official Governmental Social Media Accounts Promote HKLEAKS

Finally, as previously reported, mainland China’s state media and other governmental entities actively promoted HKLEAKS. This included not only China Central Television (CCTV) encouraging its followers on Weibo to spread the word on the campaign, but also official Weibo profiles for local Chinese governmental authorities doing so, even using a dedicated hashtag — #被摘下面罩香港暴徒名单# (“[List of Hong Kong Rioters Unmasked] Hong Kong Rioters List”) — for that purpose, as in the following example:

This behavior further indicates that the Chinese government was not only aware of the HKLEAKS campaign, but also — at a minimum — actively supporting it.

Assessment #3: HKLEAKS Was Part of a Broader Coordinated Campaign

HKLEAKS did not exist in a vacuum, but rather coordinated in various degrees with a range of other entities, some showing an overt affiliation, others fully anonymous. HKLEAKS and this network mutually benefited from reciprocal promotion. Certain parts of the network’s approach demonstrate strong similarities with the HKLEAKS modus operandi, and could have been run by the same operators.

A Network Designed to Target Multiple Different Audiences

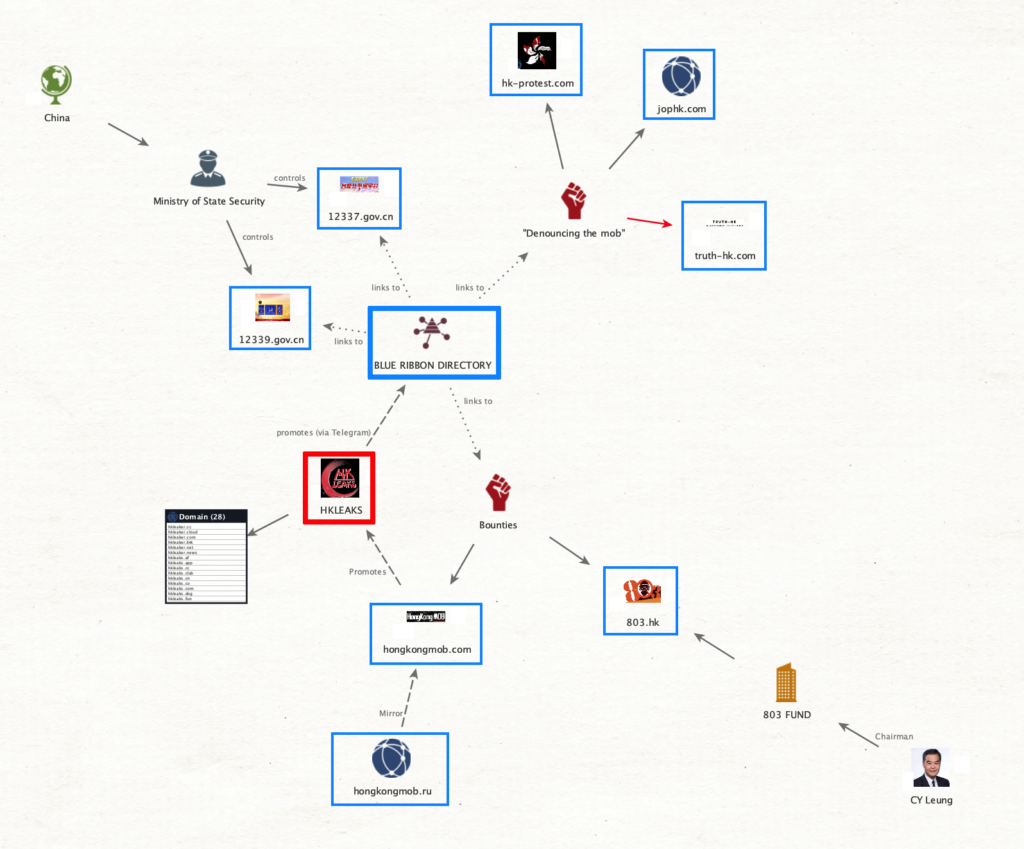

As noted in previously published analyses, HKLEAKS was connected to a broader network, self-styling as “Blue Ribbon” (from the symbol used by the faction supporting the Hong Kong police and opposing the protests), and advertised on one of its own member websites, hongkongmob[.]com. HKLEAKS connected to it in different ways, and by different degrees. The portion of this network that was directly involved in the opposition to the protests, implemented a diverse set of tactics and applied the same anonymization measures (with one notable exception) deployed by HKLEAKS.

This network also appeared to be targeted at multiple different audiences. On top of Hong Kong-targeted content, it included English content aimed at international audiences, as well as links to mainland Chinese platforms directly controlled by the Ministry of State Security.

I. The Bounties

Bounty campaigns constituted the first part of the Blue Ribbon network. This was a distinct operating model from the one used by HKLEAKS: it essentially crowdsourced the doxxing, although for the stated purpose of leading to the targets’ prosecution by the Hong Kong authorities.

This line of effort was divided into a covert version, showing some strong similarities with HKLEAKS, and an overt one, claimed by one of the highest profile political figures in Hong Kong.

The Covert Version

The website Hongkongmob[.]com was launched at the end of September 2019 and offered bounties as rewards for information that helped the Hong Kong authorities identify protesters. Like HKLEAKS, the website also claimed to represent a grassroots movement and that their objective was to enable the prosecution of protesters.

Hongkongmob[.]com exhibited the same bulletproof anonymity as HKLEAKS. Its two websites, .com and its shortly lived mirror .ru:

- No information visible for the related domains registration

- Russian-based hosting (for .ru)

- Contacts provided included three distinct email addresses from known anonymous email providers

The websites’ launch was accompanied shortly thereafter by the dissemination of a post made on the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo containing a purported “distress letter from Hong Kong” (一封來自香港的求救信). In it, the authors claimed to be “anonymous volunteers who founded the ‘Anti-Hong Kong Independence Violence Volunteer Alliance’ and ‘Protect Hong Kong Volunteer Alliance’, two purportedly grassroots organizations created to fight back against “the violent mob” in Hong Kong.

The full text of the letter contains several notable passages. Among them:

- The authors’ claim of being under attack by the protest movement: “Now, the rioters are attacking us! They launched a “flooding” campaign against us on forums promoting Hong Kong independence and nearly a hundred Telegram groups, conspiring to take over our territory, destroy our alliance, and break our will! […] They forced the Privacy Commissioner to issue a warning to us, but they wantonly exposed and harassed righteous people.”

- The framing of the protesters as powerful and well equipped: “They have a propaganda team, they have a technical department, they have fighters, they have a think tank, they have a big boss behind them, but what they don’t have is a bottom line.”

- The claim of being, in contrast, almost powerless in front of the “mob”: “And us? No money, no people, nothing. We have only a conscience and a tiny bit of power.”

The Overt Effort

The bounty model, however, was not new to the broader anti-protests landscape when HongKongMob was launched. A bounty platform had been set up around the same days as the first HKLEAKS assets in the form of the website 803[.]hk. This website, still visible online although apparently no longer updated, also offered bounty rewards in return for information on the identity and whereabouts of previously unidentified protesters. It drew its name from the date of a protest incident that occurred on August 3, 2019, in Tsim Sha Tsui, when a Chinese flag was removed from its pole and thrown into the sea.

803[.]hk was owned and operated by the 803 Fund, an organization overtly affiliated with a high-profile Hong Kong political figure, CY Leung. In fact, Leung openly claimed to be the Fund’s chairman in a post on his own Facebook profile on September 14, 2019, shortly after the launch of the 803 website:

Funding for the bounty rewards offered on 803[.]hk was claimed on the website itself to be coming from the “private sector”, with no additional details provided.

II. Mainland China Campaigns

Secondarily, the Blue Ribbon directory advertised by hongkongmob[.]com also included platforms and groups that linked back to mainland China.

We could not identify evidence of direct involvement by these assets in the anti-protests efforts in Hong Kong. Their presence in the Blue Ribbon directory is more likely to signal the HongKongMob’s operators’ intent to align their own efforts with governmental campaigns in mainland China, thus increasing their legitimacy in the eyes of their audience.

- A first set included two government websites run by the Chinese Ministry of State Security, and promoting campaigns for the reporting of threats to the country’s national security [1] [2]

- Nothing on those two websites relates to the Hong Kong context

- However, the resemblance between their campaigns (soliciting identifiable information about individuals considered as national security threats) and, especially, the Hong Kong bounty campaigns (hongkongmob[.]com and 803[.]hk) is significant. It may at least indicate an effort by the latter to imitate what was implemented in mainland China to squash dissent.

- A second group of links directed to a known online community, Di Ba (also known as D8 or Tieba). The Blue Ribbon directory included links to two Facebook groups using the naming convention “帝吧中央集团军” (Diba Central Group Army).

- “Di Ba” is a term that became known in January 2016, when an online forum community with that name emerged as an online activism force after it targeted real or perceived pro-independence Taiwanese figures in a highly coordinated brigading campaign that used thousands of existing and newly created Facebook accounts to achieve their goals

- While the ostensible nature of Di Ba as an organic online community made it a perfect actor for the Chinese government to maintain plausible deniability in regards to the responsibility for their actions, some observers had pointed out that “it would be a mistake to see these youngsters as an organized force answering the call of the Party. Their tone and style set them apart from the more uptight “online patrols” the Party dispatches to enforce its political creed”.

II. International Campaign

Finally, a third group of websites, claimed to be part of the Blue Ribbon directory, addressed English-speaking audiences with the stated goal of “denouncing the violent mob” responsible for the Hong Kong protests.

This smaller network of websites was simpler in the structure and nature of its content. It employed basic blog formats, and published pictures and videos allegedly proving unprovoked violence committed by members of the 2019 protest movement in Hong Kong. It also made use of social media to promote the websites’ content.

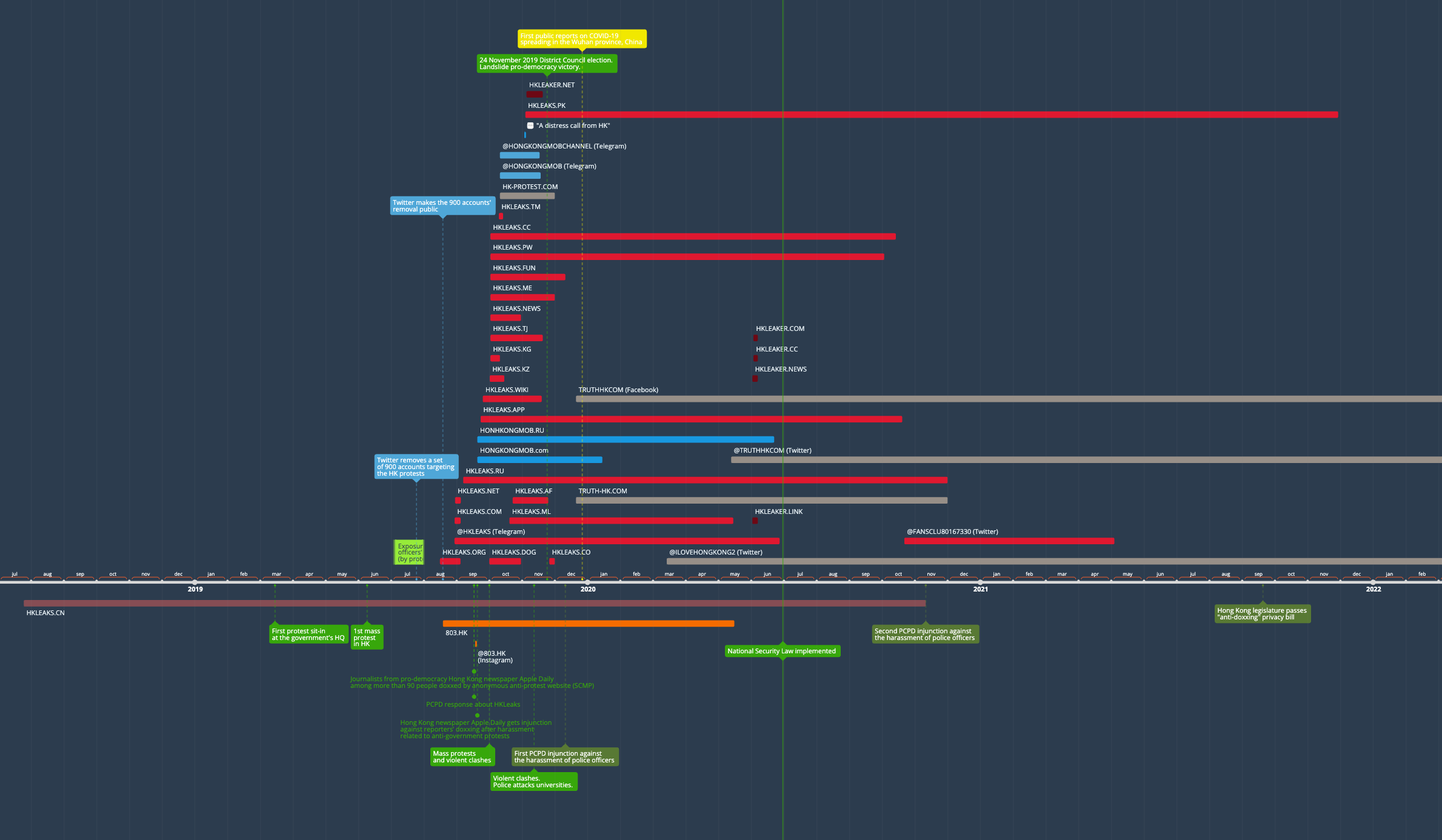

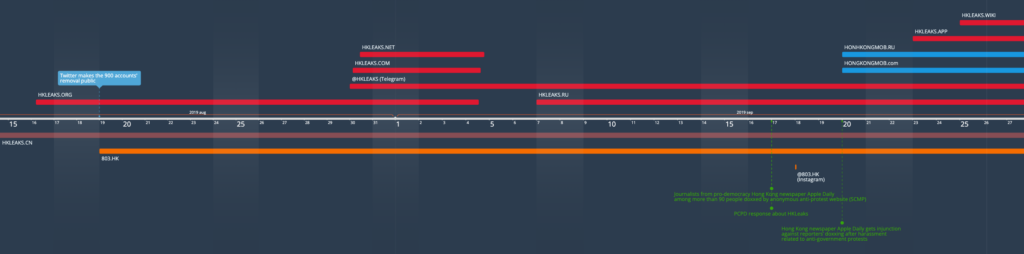

A Well-Sequenced Timeline Suggests Coordination Between The Different Assets

Some of the strongest indications of the possible coordination between the different asset families is provided by the timeline of the operations across HKLEAKS and the Blue Ribbon network, as well as the coincidence of its timing with other possibly related events. In this section, we take a birds-eye view of it, and propose to divide it in four separate phases to fully understand it.

The Full Timeline

Below, we take a holistic view of the timeline of activity for each of the main assets involved with the goal to assess the likelihood of coordination between them. For simplicity’s sake, we have decided to exclude the secondary Telegram channels replicating content from both or either the websites and their main Telegram platforms.

Legend:

- Red: HKLEAKS (doxxing) assets

- Pink/Red: hkleaks[.]cn, outlier domain that cannot be confirmed as linked to the operation.

- Orange: 803 Fund (bounties, overt organization) assets

- Blue: HongKongMob (bounties, anonymous organization) assets

- Grey: HK-Protest and Truth-HK (“denouncing the mob”) assets

- Green:

- boxes: main events that could have influenced, or even triggered, the operations

- text: events in response to the operations

- Yellow: emergence of COVID-19.

Based on the timeline of the activities, we are defining four distinct phases for the operation. Juxtaposing some major and relevant political, societal, and other events to the timeline can also help us consider their possible impact on them.

Phase 1: Inception (August-September 2019)

The initial phase for the set of HKLeaks and Blue Ribbon operations began in mid August 2019. At this stage, street protests in Hong Kong had been happening with increased intensity for approximately five months, and protesters had conducted a month-long campaign to expose the identity of police officers in July. At the end of the same month, Twitter removed about 900 accounts found to be linked to an information operation originating from mainland China, and also targeting the Hong Kong protests; the company announced the takedown on August 19.

Just three days prior to the announcement, the first HKLeaks domain (.org) was launched with its content doxxing protesters, and, on August 19, the date of the announcement, the overt bounty website 803[.]hk also began its activity. Within one month of these two ostensibly distinct assets are followed by:

- two briefly active back-up HKLeaks domains (.net and .com), and a third that will have a longer lifespan (.ru);

- the officially affiliated HKLeaks Telegram channel; and

- 803’s official Instagram account, which only posted once and ceased activity immediately afterwards.

In the meantime, both the protest movement and other targeted groups (most notably, the doxxed journalists from Apple Daily, the main independent newspaper in Hong Kong) responded by filing a claim with the PCPD, which responded in consistent fashion on September 17, both acknowledging the doxxing as illegal and admitting it had no power to remove it.

Unrest on the ground continued to escalate, however, leading to violent clashes on October 1 that continued for days. This coincided with the beginning of the second phase.

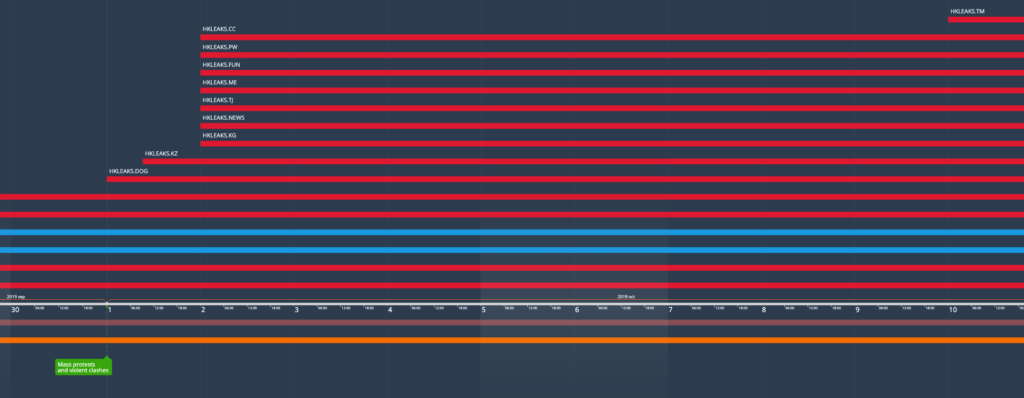

Phase 2: Full Force (September-October 2019)

We can identify the start of a second phase of the operation with the launch of the anonymous bounty websites, HongKongMob [.com and .ru], towards the end of September 2019. This coincided with a rapid escalation of the street protests to violent conflict, culminating with the clashes between the protesters and the police during the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, on October 1.

In parallel to the activation of the bounty websites, several more HKLEAKS domains were registered as back ups for the original ones, due to the repeated claims filed to the PCPD to have them removed, and to probable online attacks, such as Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) ones. A particularly notable wave of new doxxing domains was observed in the early days of October, with a total of 8 new pay-level domain (PLD)6 HKLEAKS registrations. At this stage, archived versions of the websites hosted on those domains show that the operators had already started categorizing their targets with specific pages listing for, as an example, reporters from what they called “Poisoned Apple” (Apple Daily), or “mob accomplices”. A new section also began listing incidents attributed to the “mob violence”, in a pattern that we describe in the section on the next phase “Diversification”.

Throughout the launch of this new wave of anonymous doxxing and bounty websites, the 803 Fund continued its overt intimidation of protesters by offering monetary rewards in exchange for information about their whereabouts and identity.

Phase 3: Diversification (Oct 2019 – Jan 2020)

A third, longer phase showing more stability and consistency in the operation’s behavioral signals began around mid October 2019, with more websites coming to join the Blue Ribbon network, with a notable shift in focus that we started to observe on the HKLEAKS websites: spotlighting the “violent mob”, in their own words, and addressing an international audience through the use of the English language. The precursor website was hk-protest[.]com, which was active for less than one month, although it remains visible to this day. The companion website truth-hk[.]com (and its own Facebook group) would not display similar activity until mid December.

As the violent clashes continued to rage on the streets and in Hong Kong’s universities, HKLEAKS and HongKongMob kept on with their own push. Several domains for the former either kept multiplying the network’s content, or were created anew; while the two Telegram groups for the latter started their activity at the same time as HK-Protest. Notably, it is at this stage, in the early days of November, that the “Distress Letter from Hong Kong” was spread over Weibo, soliciting the mainland audience’s help against the “violent mob”.

This phase is a continuation of the full effort seen in the weeks immediately prior, but it displays the operation expanding its activity through new tactics, including more traditional information operations using fictitious personas, and targeting a specific platform (in this case, Weibo).

Phase 4: Inertia and Deactivation (Jan 2020 – Present)

The operation lost its main momentum around the end of 2019, while keeping key assets active, albeit intermittently. Save for a small number of new HKLEAKS domains, the new creations were mainly a handful of Twitter accounts, representing both the doxxing wing (HKLeaks itself) and the more recent Truth HK website.

January 2020 was, of course, when the first confirmed reports on a novel respiratory disease out of mainland China began turning into what would shortly become a global pandemic. The subsequent lockdowns will represent a key factor in the muzzling of the street protests, and as a consequence, in a lower need for an online operation opposing them. Finally, on June 30, 2020, with the pandemic raging, the National Security Law was implemented, sealing the protests’ fate.

Some activity from the networks continued, mostly out of dwindling momentum, for a few months. The HKLEAKS and Truth HK Twitter accounts remained active, the former ceasing activity in mid 2021, the latter tuning back into the more generic pro-China political content that had featured on the network of accounts disabled by Twitter during the summer of 2019. A mirror set of websites for HKLEAKS on four pay-level domains using slightly different nomenclature (hkleaker instead of hkleaks) that had originally emerged in November also became briefly available in early June 2020.

In parallel, the 803 Fund slowed activity on its website, although some bulk updates to the list of successful prosecutions is visible, as previously mentioned, up until January 2023.

An Interconnected Network: Interactions Point to Mutual Partnerships

If analyzed in its entirety, HKLEAKS and the Blue Ribbon assets consistently interacted with each other, suggesting a shared agenda to be pursued through different tactical means more than a simple communion of intent.

HKLEAKS and HongKongMob

Within the self-styled Blue Ribbon network, HKLEAKS was most similar to HongKongMob, the set of two mirror websites offering bounties on behalf of a purported volunteer organization.

Examples of signals indicating a likely overlap between the operators for the two sets of websites include:

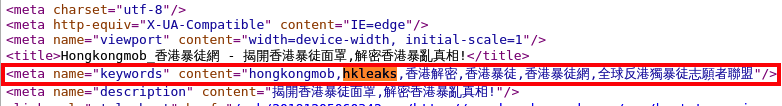

- Code: the strongest indication of HongKongMob’s direct affiliation with the HKLEAKS network of websites comes from the website’s HTML code in one of its earliest Wayback Machine captures (December, 5, 2019).

- The HTML <meta> tags of the website, under the <meta name=”keywords”> section, where the website’s developer can insert keywords (not otherwise visible to the website’s visitors) for search engines, include hkleaks and 香港解密 (Hong Kong Declassified, another name used for HKLEAKS) as two of such keywords.

- The other keywords included all directly relate to the HongKongMob website, or the underlying organizations claimed to be responsible for its management.

- Linkages: on occasion, HongKongMob included a few HKLEAKS domains as part of the Blue Ribbon directory. For example, this is visible on a November 1, 2019 Wayback Machine capture, where the hkleaks[.]dog, .news and .af domains are linked.

- Timeline: two web domains and at least two Telegram channels created in the span of little more than one month, coinciding with the “second wave” (September––October 2019) of HKLEAKS domains (16 in total) being launched;

- OpSec: no information visible for the domains registration; Cloudflare protection on both domains (.ru and .com); Russian-based hosting (for .ru); two distinct email addresses from known anonymous email providers as the given contact:

- hongkongmob@protonmail[.]com

- hongkongmob@163[.]com – a Chinese-based mainstream provider allowing the creation of free personal email addresses.

- Layout: strikingly similar to the HKLEAKS websites. Like them, the header for HongKongMob contains the single email address supplied as contact; a guarantee that “the whistleblower information will not be leaked”; and a slogan overimposed to a graphic banner. Both sets of websites also commonly utilized a “megaphone” icon to highlight their main statements.

- Affiliation: the HongKongMob network also claims to be the work of “free netizens” working “for those Hong Kong neighbors who have been beaten, hurt, and harassed, for the entire Chinese people, Chinese people around the world, ethnic Chinese, and all those who love Hong Kong and pursue justice and truth” until “the mob cockroaches are completely eradicated,” in an example of the violent rhetoric that is typical to both HongKongMob and the HKLeaks websites.

HKLEAKS and the Blue Ribbon Network

Several other indicators point to a broader coordination between the HKLEAKS operation and part of the Blue Ribbon network.

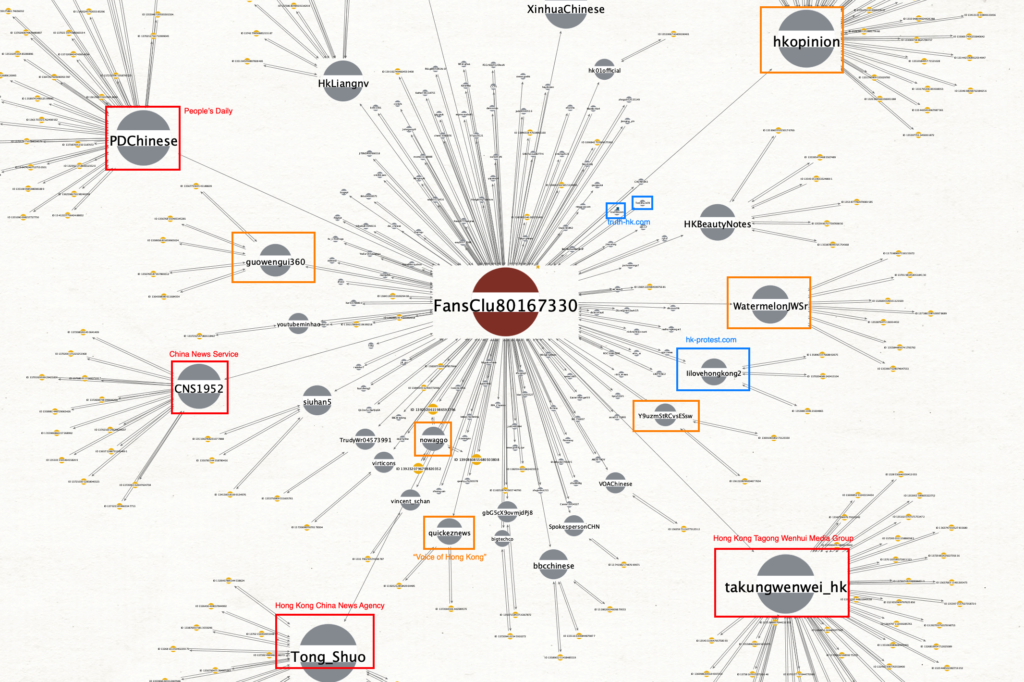

For example, we conducted an analysis of the whole set of tweets posted by a Twitter account, @FansClu80167330, created in May 2020, and which became active only in October of the same year. This profile utilized the same iconography as HKLEAKS, and promoted its domains by posting the HKLEAKS websites’ doxxing cards.

To conduct the analysis, we downloaded the account’s tweets, and visualized the engagement dynamics in Maltego. The following diagram shows the level of interaction that the profile (at the center of the picture) had with other Twitter accounts. For the purpose of this analysis, interactions are defined through the following criteria:

- Followers

- Following

- Retweets of [resulting account]

- Mentions of [resulting account]

The bigger the bubble’s size in the diagram, the more interactions that @FansClu80167330 had with the related Twitter profile.

The analysis surfaced several trends:

- The highest level of engagement is with profiles that Twitter has labeled as Chinese state media entities (red boxes).

- These accounts are typically mentioned and/or retweeted by the HKLEAKS profile

- The interaction is unidirectional – meaning that there is no visible response coming from them towards @FansClu80167330

- A secondary level of interaction happens with a set of profiles that, while not representing state media entities, express clear pro-Beijing political views, often interspersed with spam content (orange boxes).

- These accounts present strong similarities with those removed by Twitter in August 2019, in that they do not appear to represent existing individuals or organizations; mix spam and political commentary; and at times, link back to themes that were seen as a strong focus for the information operation identified by Twitter

- For example, the account @guowengui360, which was likely originally created to target the exiled Chinese businessman we had seen as regularly targeted in Chinese state-aligned operations

- In this case, however, the engagement with @FansClu80167330 is bidirectional: The profiles follow the HKLeaks account back, and at times, retweet its content

- These accounts present strong similarities with those removed by Twitter in August 2019, in that they do not appear to represent existing individuals or organizations; mix spam and political commentary; and at times, link back to themes that were seen as a strong focus for the information operation identified by Twitter

- A fraction of the accounts that @FansClu80167330 interacts with can be identified as representing the Blue Ribbon network (blue boxes).

- The related Twitter profiles linked directly to websites belonging to that network in their bio

- Engagement with them is minor

- Notably, one of the accounts in this group has the screen name @ilovehongkong2: A quick review of the screen name @ilovehongkong (which was possibly its first iteration) shows that it had been disabled by Twitter as abusive, although we cannot confirm that it had been part of the 2019 sets due to the screen names for the accounts with less than 5000 followers being hashed

Finally, it was HKLEAKS itself that, on its main Telegram channel, advertised several Blue Ribbon websites, among which are hongkongmob[.]com, hk-protest[.]com, 803[.]hk, and 12339[.]gov.cn.

Assessment #4: HKLEAKS was a Well-Resourced Campaign

Access To Personal Data

HKLEAKS likely also had access to privileged information on the individuals it targeted. According to multiple sources, such information could only be obtained from a state entity.

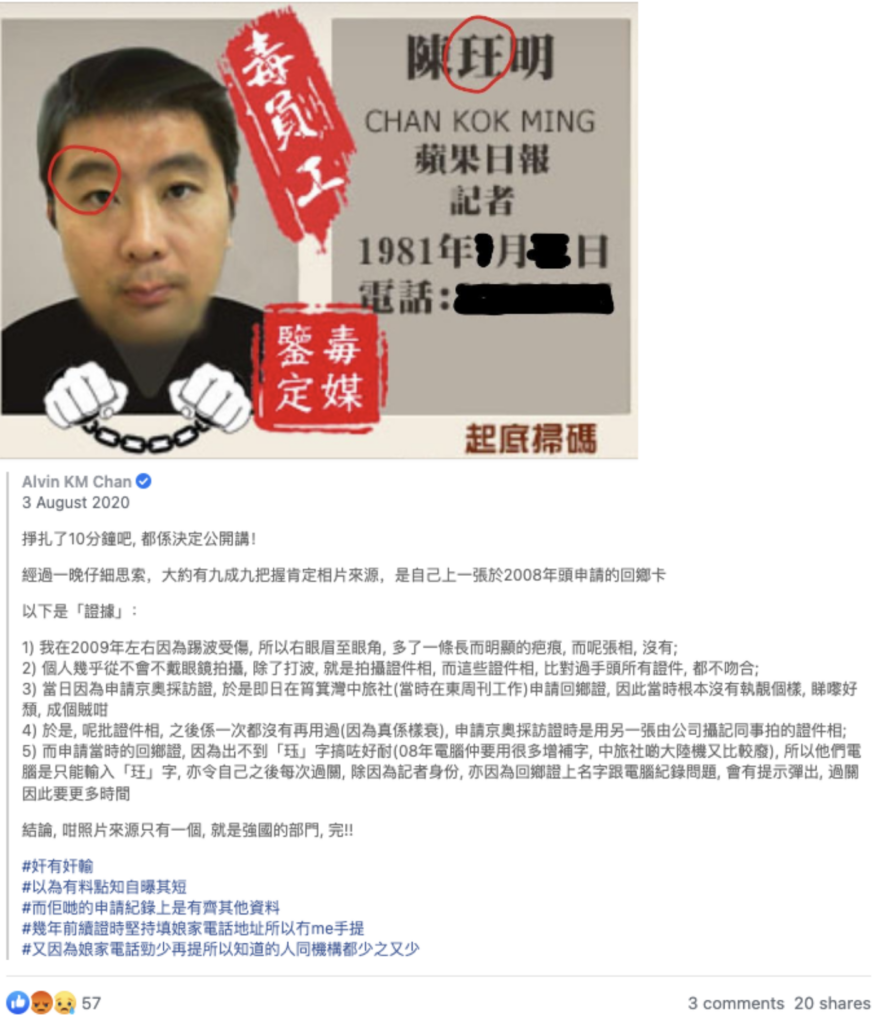

At the outset of the doxxing campaign, several people targeted by HKLEAKS flagged that the information posted about them was not publicly available. The Hong Kong based and pro-democracy news outlet Apple Daily, of which the staff themselves were targeted by HKLEAKS via a dedicated section of its websites, reported that “a number of victims told Apple [Daily] that they questioned the source of the leaked data, possibly involving the mainland public security departments. The “mugshots” of at least two people that were published on the website were photos submitted by China Travel Service Hong Kong when they applied for the “Home Return Card”. The same batch of photos has never been made public.

The China Travel Service (CTS) is Beijing’s state-owned travel agency, and the only one authorized to process travel permits between Hong Kong and mainland China. According to press sources, Apple Daily reported to the PCPD that about one-third of the more than 120 employees of the newspaper doxxed by HKLEAKS “suspected their circulated photos came from their mainland travel permit applications”. Alvin KM Chan, a Hong Kong based pro-democracy reporter, in August 2020 posted a detailed explanation on Facebook of how he had concluded that the data used for his doxxing card could only have come from his 2008 travel permit application to CTS. It did not show a scar under his eyebrow that he has had since 2009; and the lettering on his name included the word “玨” which, while incorrect, was the only one that the CTS computer at the time would accept for the related part of his name.

Following the initial press reports on the potential leak of private information from the CTS, the agency responded to one of the outlets reporting it — Hong Kong Free Press — by vehemently denying the mishandling of personal data, and threatening legal action against “individuals and media reporting that distort the facts”. It did not, however, address the merit of the allegations, or the evidence produced in their support.

Additionally, other reports pointed to a potential sourcing of the leaked information from the mainland Chinese customs authorities. This would represent an even more direct link between HKLEAKS and governmental entities.

High-Volume Content Production and Maintenance

HKLEAKS conducted sustained content production and regular maintenance of its digital assets throughout its life span.

Since its inception in August 2019 until its most recent iteration (the still visible — as of May 2023 — hkleaks[.]pk), HKLEAKS underwent regular updates, for a high volume of doxxing content published on its websites.

The first version, hkleaks[.]org (August 2019), was simply a basic list of doxxing targets with the related digital cards, displaying their personal identifiable information (PII). The initial target count was of no more than 60 individuals — 57 on a capture from September 1, 2019. This evolved into a first iteration of the model, visible on hkleaks[.]ml, where the website’s sections were expanded and diversified: the doxxing targets were then divided into different categories, as explained previously in this report.

The aforementioned website hkleaks[.]pk was based, and further expanded,on this latter model.

- Its list of doxxing targets reached a total of 2,800, the final count for the entire operation

- The website’s structure was more complex, and the doxxing was integrated with:

- political commentary about mainland China and other countries;

- an archive of alleged “atrocities” committed by protesters; and

- a collection of “decrypted rumors” in the form of anonymous opinion pieces attacking the credibility of the protest movement, or insinuating the involvement of foreign powers in their support

This final operating model denoted the high likelihood that dedicated staff with professional skills were involved with time allocated for the maintenance of the website. The backend activity required to produce this volume and type of content must have included, at the very least the:

- sourcing and vetting of the PII for almost 3,000 targets;

- tracking of domestic and international news about the protests;

- production of a substantial amount of blog posts commenting on such news;

- graphic and structural evolution of the website itself; and

- website infrastructure maintenance, also given the alleged attacks that HKLEAKS sustained throughout its activity.

Professional Design

HKLEAKS had access to professional web design, including custom graphic design, and developed its own recognizable layouts and visuals.

Throughout the operation’s lifespan, HKLEAKS displayed distinctive imagery that appeared proprietary to its websites. For example, starting in late 2019, and up to 2023, each doxxing card had a consistent layout, with the image of a rifle’s crosshair overimposed to the target’s face:

HKLEAKS also had its own logo available and in use since the first publication of a doxxing website. It was then consistently used by the operators across the different versions of the operation’s websites.

Conclusions

HKLEAKS’ Nature and Legacy

The HKLEAKS campaign has subsided, but that was hardly due to any headwinds it faced. In fact, it continued to dox thousands of Hong Kong protesters, journalists, teachers and lawmakers for several years, and its output is still publicly visible on one iteration of its websites.

The network claimed to be grassroots and volunteer driven. It claimed to be the underdog, that it had “little resources and no voice”. But our findings indicate that this is almost certainly not the case. It is highly unlikely that HKLEAKS was an organic or authentic campaign. Our findings show that it was specifically designed to avoid attribution; that it was well coordinated with other digital assets, including with mainland Chinese state media; that it had ties to the mainland; and that it was well resourced.

Analyzing the available evidence, we can therefore conclude that HKLEAKS was an artificial, well-crafted influence campaign designed to help suppress the protest movement, and that, at a minimum, it received support from Beijing.

The role of the Hong Kong authorities is noteworthy. In 2019, then privacy commissioner Stephen Wong declared that HKLEAKS was a violation of the personal data privacy ordinance, and that he had requested the website to take the illegal content down. However, he also added that since the website was located outside of the Hong Kong jurisdiction, there was little he could do in terms of enforcement. As a matter of fact, a critical part of the HKLEAKS strategy was to play musical chairs of sorts with domain names, most likely to dodge this kind of legal request for takedown. The currently visible version of its website is located at a .pk (the Pakistani extension) domain name, and hosted by the same Russian service provider that has sheltered the operation since its inception, a provider notorious for hosting content that other hosting services refuse to host.

In other words, the Hong Kong authorities could claim that their hands were tied with regards to the privacy violations HKLEAKS was clearly engaging in. They could claim that they have done all that they could have done.

But this was back in 2019. In 2022, the Hong Kong authorities adopted an amendment to the personal data privacy ordinance that specifically targeted doxxing. Amongst other actions, it has granted the privacy commissioner’s office the power to block websites found to contain doxxing content. However, even with the new powers of the amendment, the current privacy commissioner Ada Chung has refused to comment on the website, while the Hong Kong police have not taken any actions to either remove the offending content or investigate its origins. In effect, as the cited Hong Kong Free Press article implies, the amendment to the personal data privacy ordinance has been toothless to do anything about the doxxing of protesters, either for political or other reasons.

Future Research – The Impact of Doxxing

While the direct effects of HKLEAKS and doxxing on activists and civil society groups is beyond the scope of this paper, our analysis nonetheless raises salient questions about the impact of such activities on individuals as well as the movement as a whole. Future research should therefore ask to what extent did doxxing suppress the whole movement’s activity, in addition to the personal and individual costs?

More broadly, a subsequent question is what are the implications of these findings for internet freedom? We argue that HKLEAKS is a case that presents broader digital rights implications that go beyond Hong Kong, or even China. For example, it is well documented in research and reporting conducted by the Oversight Board, the organization created to help the social media platform Facebook “answer some of the most difficult questions around freedom of expression online: what to take down, what to leave up and why”, that doxxing “can have some serious and lasting implications for vulnerable individuals, putting their safety at risk and endangering their livelihoods and mental well-being.” This research pertained to a completely different set of countries (Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia), showing that the threat does indeed have a global implication.

In summary, doxxing, the exposure of PII with the purpose of causing harm, is a powerful weapon which is largely unregulated, although some sparse legislation around the issue has started to emerge. In the hands of resourced threat actors, such as a government or its proxies, its firepower increases exponentially while the available defenses to civil society remain unchanged. The inherent imbalance of power between attacker and attacked, similarly as for other forms of coordinated online harassment, becomes a central point that warrants future research.

Lastly, if HKLEAKS was conducted by either (or perhaps, both) the Chinese and Hong Kong governments, our analysis suggests that there are no serious repercussions for the state in doxxing its own citizens, and that other governments could rapidly learn how to use this attack method effectively. Given the lack of consequences and relatively low barriers to entry, future scholarship should also explore to what extent will other authoritarian states copy similar tactics? If digital repression is about raising the cost of activism, then the HKLEAKS case suggests that doxxing can be a fairly low risk but potentially high reward instrument of digital repression.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank an anonymous researcher for contributing to this report. We would also like to thank Pellaeon Lin, Justin Lau, Gabrielle Lim, Emile Dirks, John Scott-Railton, Bill Marczak, Jakub Dałek, “Mike”, and an anonymous reviewer for valuable input, and peer review. Research for this project was supervised by Ron Deibert.

Appendix

Content Samples

HKLeaks

Logo

“Solemn Statement”

Doxxing Cards

WeChat (Content Dissemination)

Weibo (Content Dissemination)

Telegram

The Blue Ribbon Directory

Bounty Campaigns

HongKongMob

803[.]hk

International Audiences Network

Other

“A Distress Call From Hong Kong”

The full text of the letter (the original Chinese one, and its English translation) can be seen below. After an introduction of the organizations purported to be behind the letter, it gives an overview of the protests from the authors’ point of view. It then points readers towards the website hongkongmob[.]com, created “to release unedited crime scenes and reveal the truth.” The letter ends with an emotional plea to the readers not to abandon Hong Kong, should the authors, who claim to have “no money, no people, nothing […] Only a conscience and a tiny bit of power” succumb to alleged attacks by the protesters.

Note: the original text of the letter is in traditional Chinese, common in Hong Kong, and not its simplified version, typically used in mainland China.

| 一封來自香港的求救信 | A distress letter from Hong Kong |

|---|---|

| 我們是創立「反港獨暴力志願者聯盟」和「守護香港志願者聯盟」的匿名志願者。

四個月以來,香港暴徒塞地鐵、塞機場、封馬路,圍政總、衝擊警署,破壞公私財物,侮辱國旗國徽,攻擊記者遊客,甚至隨意曝光警員及其家庭成員之隱私,煽動非禮警員的老婆,虐待尚在幼稚園的警員兒女。這些違法行為,觸目驚心!今日的香港已經滿目瘡痍,全球華人都心痛萬分、無法接受! HONG KONG TEARS A RIVER! 我們這些正義的志願者們終於忍無可忍,選擇不再沉默!我們創建「香港暴徒網」(http://hongkongmob.com),曝光沒有經過剪輯的犯罪現場,公佈事實真相。2019年10月5日,香港開始實施《禁止蒙面規例》,我們在Hongkongmob上發起「全民撕面罩活動」,呼籲市民向警方提供線索。加入我們的人越來越多,每天都有熱心市民向我們提供線索。 現在,暴徒們開始狙擊我們! 他們在宣揚港獨的論壇和近百個Telegram群組對我們發起「洗版」行動,企圖攻陷我們的陣地,摧毀我們的聯盟,擊垮我們的意志! 他們用最惡毒的語言人身攻擊我們。 他們用最卑鄙的網路手段攻擊我們的網站。 他們強迫隱私專署對我們發出警告,自己卻肆意曝光、騷擾正義人士. 他們發起手足對我們的聯絡群組進行瘋狂洗版。 他們潛入我們的社交平台,偷走所有群成員資料,然後逐個曝光、威脅。 他們有文宣組,他們有技術部,他們有勇武派,他們有智囊團,他們有背後大台,但他們沒有底線。 而我們?沒有錢,沒有人,什麼都沒有。我們只有一顆良心和一點點微薄之力。 我們的網站被攻擊,連我們的「曝光墻」也被迫下線。而他們的攻擊,還在持續,而且仲越來越瘋狂。面對攻擊,我們不知道還能支持多久?我們聯盟的成員會不會有危險。 為了被打、被傷害、被騷擾的街坊市民,為了全中國人民、全球華人、華裔以及所有熱愛香港、追求公義同真理的人,為了良知和公義!我們絕不會向暴徒曱甴們低頭!我們絕不會退縮! 如果我們倒下,請你仍然相信:紫荊花依舊美麗。請你不要拋棄香港。好嗎?拜託! 朋友,如果你看到這封信,請傳播事實的真相!請你幫助阻止香港暴徒的暴行!請救救我們的聯盟,救救我們的網站。救救香港! GOD Bless HongKong! 其實, 我們的理想好簡單: 願和平的天空沒有烏雲, 平靜的大地沒有傷害, 沉默的人不再遭受暴力, 失去理性的人迷途知返, 飄搖的香港,回歸安寧! 反港獨暴力志願者聯盟 守護香港志願者聯盟 |

We are anonymous volunteers who founded the “Volunteer Alliance Against Hong Kong Independence and Violence” and the “Protect Hong Kong Volunteer Alliance”.

In the past four months, rioters in Hong Kong have blocked the subway, the airport, the roads, surrounded the government headquarters, stormed the police station, destroyed public and private property, insulted the national flag and national emblem, attacked journalists and tourists, exposed the identity of police officers and their family members recklessly, incited sexual harassment of the wives of the police, and bullied the police’s children who were still in kindergarten. These illegal acts are shocking and outrageous! Today’s Hong Kong is devastated, and Chinese people all over the world are heartbroken and find this unacceptable! HONG KONG TEARS [sic] A RIVER! We righteous volunteers finally couldn’t bear it anymore and chose not to be silent anymore! We created the “Hong Kong Mob Network” (http://hongkongmob[.]com) to release unedited crime scenes and reveal the truth. On October 5, 2019, Hong Kong began to implement the “Prohibition of Face Mask Regulations”. We launched the “National Mask Tear Off Campaign” on Hongkongmob, calling on citizens to provide clues to the police. More and more people are joining us, and enthusiastic citizens provide us with clues every day. Now, the rioters are attacking us! They launched a “flooding” campaign against us on forums promoting Hong Kong independence and nearly a hundred Telegram groups, conspiring to take over our territory, destroy our alliance, and break our will! They attack us personally with the most vicious language possible. They attack our website with the most despicable online attacks possible. They forced the Privacy Commissioner to issue a warning to us, but they wantonly exposed and harassed righteous people. They got their people to massively flood our contact groups. . They infiltrated our social media, stole the personal information of our group members, and then doxxed them and threatened them one by one. They have a propaganda team, they have a technical department, they have fighters, they have a think tank, they have a big boss behind them, but what they don’t have is a bottom line. And us? No money, no people, nothing. We have only a conscience and a tiny bit of power. Our website was attacked, and we were even forced to take offline our “exposure wall”. And their attacks are still going on, and they are getting more and more crazy. In the face of these attacks, we don’t know how long we can resist? We don’t know if members of our alliance will be in danger? This is for all our friends who were beaten, hurt, and harassed, for all the Chinese people, the Chinese overseas and abroad, and the ethnic Chinese, and for all those who love Hong Kong and pursue justice and truth, this is for conscience and justice! We will never bow to the rioters and the cockroaches! We will never back down! If we fall, please still believe: the Bauhinia is still beautiful. Please don’t abandon Hong Kong. Okay? Please! Friends, if you see this letter, please spread the truth! Please help stop the violence of the Hong Kong rioters! Please save our alliance, save our website. Save Hong Kong! GOD Bless Hong Kong! Actually, our ideals are simple: May the peaceful sky be free from dark clouds, May the peaceful earth be free from harm, May the silent man be free from violence, May the people who have lost reason find their way back, May restless Hong Kong return to peace! Volunteer Alliance Against Hong Kong Independence and Violence Protect Hong Kong Volunteer Alliance |

Indicators

Web Domains

HKLeaks & HKLeaker

| DOMAIN | CREATION DATE | SELECTOR | SELECTOR TYPE | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hkleaks[.]org | 2019-08-16 | Hosted on Cloudflare between Aug 17, 2019 and Aug 28, 2019. | ||

| hkleaks[.]net | 2019-08-30 | |||

| hkleaks[.]ru | 2019-09-06 | |||

| hkleaks[.]wiki | 2019-09-27 | |||

| hkleaks[.]kz | 2019-10-01 | ueonefind@protonmail[.]com | Most likely bogus registration details. The email address is not used for other domain registrations. The street address is mentioned on two fashion e-commerce websites cached by Google; it is unclear whether they were ever functional. | |

| Yoshida Yuki | Registrant Name | |||

| [Private residential address in Japan. We assess likely that the operators had selected it randomly, and we are therefore masking it to preserve the privacy of the legitimate owner.] | Registrant Address | |||

| hkleaks[.]dog | 2019-10-01 | |||

| hkleaks[.]pw | 2019-10-02 | S5k9uP2ya@protonmail[.]com | Most likely bogus registration details. The email address is not used for other domain registrations. The phone number was also utilized to register hkleaks[.]kg. | |

| Yamakado Chie | Registrant Name | |||

| [Private residential address in Japan. We assess likely that the operators had selected it randomly, and we are therefore masking it to preserve the privacy of the legitimate owner.] | Registrant Address | |||

| +81697****** | Phone Number | |||

| hkleaks[.]cc | 2019-10-02 | Anonymized – WhoisProxy[.]ru on DDoS-Guard name servers | ||

| hkleaks[.]me | 2019-10-02 | |||

| hkleaks[.]fun | 2019-10-02 | |||

| hkleaks[.]news | 2019-10-02 | |||

| hkleaks[.]kg | 2019-10-02 | |||

| hkleaks[.]tj | 2019-10-02 | sdfjksldme@protonmail[.]com | Likely bogus registration details. Anonymous email address, not used elsewhere in domain registrations data.

The registrant name was assessed by native Chinese speakers as likely made up; and the address was probably selected randomly, given the lack of any visible connection to relevant individuals and/or organizations. |

|

| San ChiNan | Registrant Name | |||

| [Private residential address in Hong Kong. We assess likely that the operators had selected it randomly, and we are therefore masking it to preserve the privacy of the legitimate owner.] | Registrant Address | |||

| +85229****** | Phone Number | |||

| +85229****** | ||||

| hkleaks[.]tm | 2019-10-14 | |||

| hkleaks[.]ml | 2019-10-20 | spiker@elude[.]in | Most likely bogus registration details. The email address and registrant name are not used for other domain registrations.

The email address is registered on an anonymous email provider hosted on the Tor Network. |

|

| Mr Nori Tsukiji | Registrant Name | |||

| [Private residential address in Japan. We assess likely that the operators had selected it randomly, and we are therefore masking it to preserve the privacy of the legitimate owner.] | Registrant Address | |||

| +81832****** | Phone Number | |||

| hkleaks[.]club | 2019-10-23 | |||

| hkleaks[.]af | 2019-10-23 | |||

| hkleaks[.]pk | 2019-11-10 (date of the first resolution on DDOS-Guard. The domain had likely been first registered earlier, although it cannot be confirmed if by the same actors.) | |||

| DOMAIN | CREATION DATE | SELECTOR | SELECTOR TYPE | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hkleaker[.]net | Anonymized – WhoisGuard | |||

| hkleaker[.]news | ||||

| hkleaker[.]link | ||||

| hkleaker[.]com | ||||

| hkleaker[.]cc | ||||

| hkleaker[.]cloud |

Unconfirmed

| Unconfirmed |

| hkleaks[.]app |

| hkleaks[.]co |

| hkleaks[.]cn |

| hkleaks.wordpress[.]com [WORDPRESS] |

HongKongMob

| DOMAIN | CREATION DATE | SELECTOR | SELECTOR TYPE | NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hongkongmob[.]com | 2019-09-20 | Registrar: NameCheap, Inc. | ||