The past two weeks brought several important developments from Google related to online identity. The big story was Google’s revision to its Privacy Policy and Terms of Service which will go into effect March 1 and uniformly govern most of Google’s services. A smaller development was Google’s update to its Google+ service “real names” policy, which has evolved slightly and now permits verified pseudonyms. And finally Google quietly, but no less importantly, revamped its account signup process.

While the changes are not yet set in stone, it appears Google has put in place pieces necessary to help verify a user’s online identity. Going forward Google will collect new users “real” name, date of birth, and gender during account registration, there is no need for users to also use Google+. Google will also have the ability to combine the same information for all other users under its proposed Privacy Policy. In addition to this user information, Google can derive (i.e., not collect directly) from users interactions valuable location information, e.g., postal code. Google collects IP addresses of users host machines which can be geolocated. For users of an Android mobile devices Google can determine user location even more precisely.

This raises a question. By adopting the various policy changes mentioned, does Google now have an ability to evaluate the veracity of user information associated with accounts?

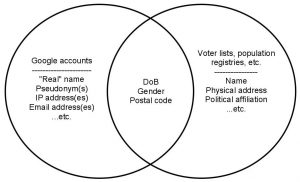

This possibility arises from the well-known ability to re-identify individuals by linking disparate data sets. E.g., Sweeney (2000) examined de-identified health records and voter lists and showed that, by cross referencing three user attributes (i.e. DoB, gender, and postal code), 87% of the U.S. population could be uniquely identified. That basic method was repeated as recently as 2010, when Koot, Noordende, & de Laat showed that 99.4% of the Dutch population could be unambiguously identified in the same manner.

Figure 1: Data sets linked via user attributes

As illustrated, by combining certain attributes about its users with other available data sources, Google can likely determine with a high level of certainty whether the user attributes associated with an account match attributes in other authoritative data sets. For example, Google can likely verify whether the “real” name a user associated with an account is actually a name (as represented in some authoritative data set) or just another pseudonym.

To be clear, Google is not requiring a user to enter personally identifiable information to register an account. One can still submit fictitious data and ostensibly maintain an anonymous Google account. The point is they probably know its fictitious. Given Google’s known interest in becoming an identity provider and that it is one of a handful of IdPs certified for providing access to certain low-level U.S.G. agency services online, Google has likely designed a pretty good way to determine the veracity of information provided by users. This should not be a surprise. Being able to scale this capability to the size of Google’s user base is fundamental to growing its identity and other lines of business (e.g., advertising). Nonetheless, it should also raise flags for privacy advocates about the need to govern online identity and attribute providers and the information they handle.