This report describes two attacks observed in mid-June 2013 targeting the Syrian opposition.

-

Malware masquerading as the circumvention tool Freegate.

-

A campaign masquerading as a call to arms by a pro-opposition cleric.

Introduction

Syria’s opposition has faced persistent targeting by Pro-Government Electronic Actors (PGEAs) throughout the Syrian civil war. A pro-government group calling itself the Syrian Electronic Army has gained visibility in recent months with high profile attacks against news organizations. Meanwhile, Syrian activists continue to be targeted with online attacks apparently for the purposes of accessing their private communications and stealing their secrets.

Throughout 2012, attacks against the Syrian opposition were documented in an extensive series of blog posts by Morgan Marquis-Boire and Eva Galperin with the help of the Electronic Frontier Foundation.1 Many others have also contributed to research on Syrian malware, from Telecomix to a range of security companies. Meanwhile, the Syrian opposition, and several groups working closely with it, such as Cyber Arabs, have been active in attempting to identify potential threats and warn users.

Researchers have identified a common theme among the attacks against the Syrian opposition: sophisticated social engineering that is grounded in an awareness of the needs, interests, and weaknesses of the opposition. Attacks often play on curiosity or ideology to encourage users to enter passwords or click on enticing files, or exploit fears of hacking and surveillance with fake security tools. Attacks are often transmitted to potential victims from the accounts of people with whom they are familiar.

The two attacks that are described in this blogpost follow this theme. One is a malicious installer of the circumvention tool Freegate. The other is an e-mail attachment calling for jihad against Hezbollah and the Assad regime or promising interesting regional news.

Attack 1: A Helping of Malware with that Proxy?

In this attack, which we first observed in the second week of June, the potential victim is encouraged to visit a download link containing a malicious installer of Freegate.

Freegate is a standalone circumvention-bypassing Virtual Private Network (VPN) client for Windows. Legitimate versions of the Freegate software are available for download on its website. While initially developed for mainland Chinese users, the software is used in a number of other countries.

While Freegate was erroneously labelled a Trojan by one anti-virus company nearly a decade ago, in this attack, attackers packaged what appears to be a legitimate version of Freegate with a malicious implant.2 The targeted group were members of the Syrian opposition in a private social media group.

When a potential victim visits the link, they are offered the download of a file which MediaFire lists as uploaded on June 15, 2013.

The zip file extracts to a MS Windows executable file.

The binary was compiled at 2013-06-15 22:41:31 UTC and has the following properties:

Similar to previously observed malware attacks targeting the Syrian opposition, this was written in .NET and appears to require the .NET 3.5 framework to execute.5

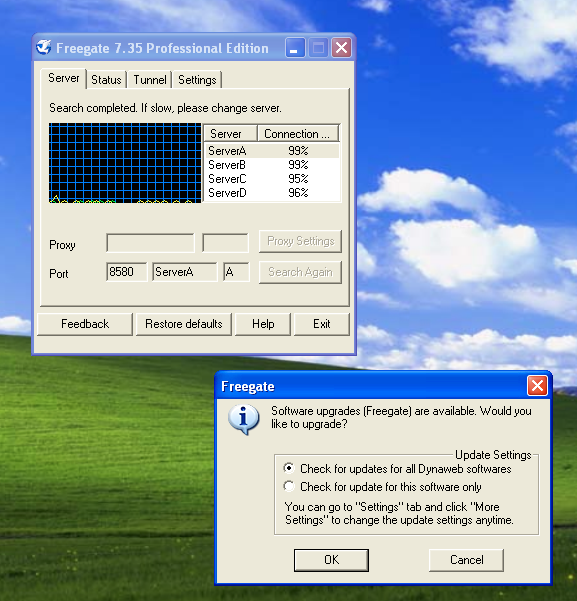

When VPN-Pro.exe is run, the victim is shown the Freegate end-user license agreement (EULA) dialogue box.6 Upon agreeing to the EULA, an operational copy of Freegate proxy is launched, which includes a request to unblock the firewall. The copy of Freegate launched is listed as “Freegate 7.35 Professional Edition.” The Freegate software begins operating, and quickly prompts the user for an update.

Infection

In addition to running a legitimate copy of Freegate 7.35,7 the malware installs an implant.

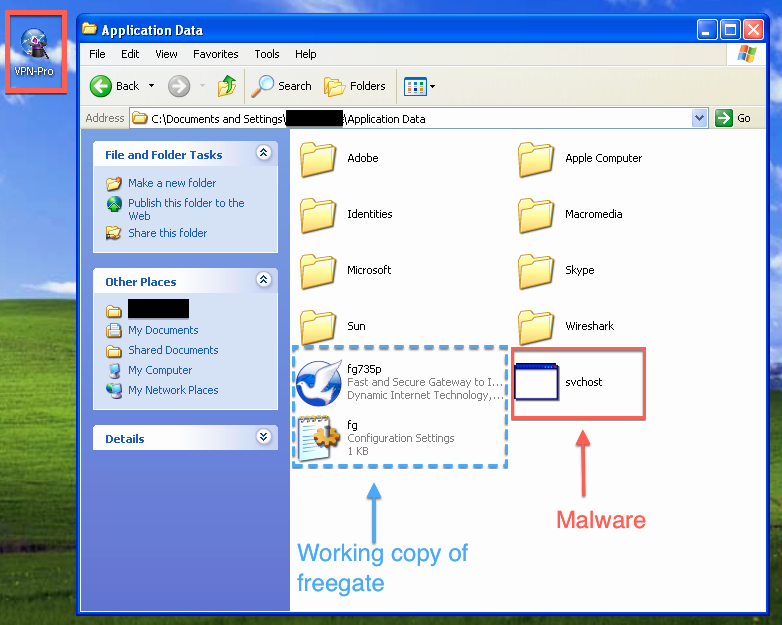

A fake “svchost.exe” is installed in the victim’s Application Data directory.

Dropped files on execution of VPN-Pro.exe:

Examination of the “svchost.exe” binary shows multiple references to “ShadowTech Rat.”

Examination of network traffic also identifies the implant as ShadowTech RAT.

Packet capture on port 1321/tcp:

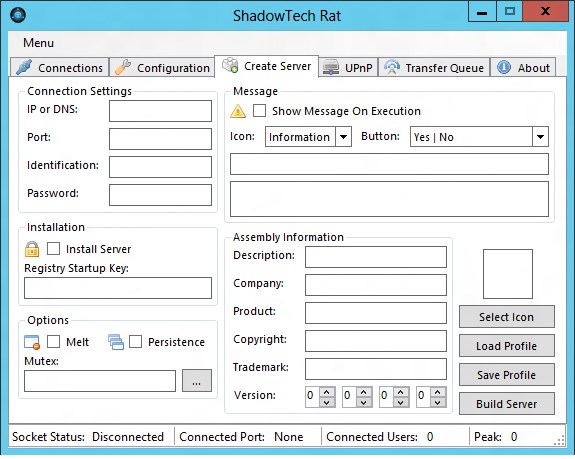

ShadowTech Rat is a Remote Access Trojan which appears to be widely available for download on both English and Arabic language sites. Videos can be found on YouTube demonstrating its functionality. The tool offers a range of options to the attacker, from keylogging and remote activation of the webcam to file exfiltration.

ShadowTech RAT control console:

Both VPN-Pro.exe and svhost.exe have been submitted to VirusTotal:

Both have relatively low detection rates by anti-virus software. As of June 20, 2013, svchost.exe was only detected by four out of 47 tested anti-virus programs, while VPN-Pro.exe was only detected by five out of 46.

The svchost.exe initiates an outbound connection to a command and control (C2) server hosted at thejoe.publicvm.com. This domain resolves to an address inside Syrian IP space: 31.9.48.119.

This is not the first time that malicious installer packages have been created for circumvention tools. In 2012, malicious installers for Green Simurgh—a standalone proxy intended for Iranian users but also used by some Syrians—were found in circulation. The creators of Green Simurgh responded by posting a prominent warning on their website highlighting the presence of these malicious installers. Last year, malware which purported to be the Tor Browser Bundle was found in the wild. It was found to be backdoored by Gh0st RAT and exfiltrated data to an IP in China.

An attack using a malicious installer of a working and reputable security or proxy tool is especially pernicious as it targets users who likely recognize the importance of privacy and circumvention, and may believe that they have increased their privacy and security by installing the tool.

Attack 2: A Targeted Call to Arms

In this campaign, contact with targets was initiated through phishing e-mails, chat messages and Facebook posts. Although we became aware of this campaign in early June, we have evidence that it may have started as early as January 2013. We believe that this campaign targeted—at least in part—high-profile members of the Syrian opposition. Interestingly, the attack included targeting of at least one non-public address associated with internal opposition communications. This indicates some degree of prior penetration of the opposition—either through computer network intrusion or other intelligence gathering activities.

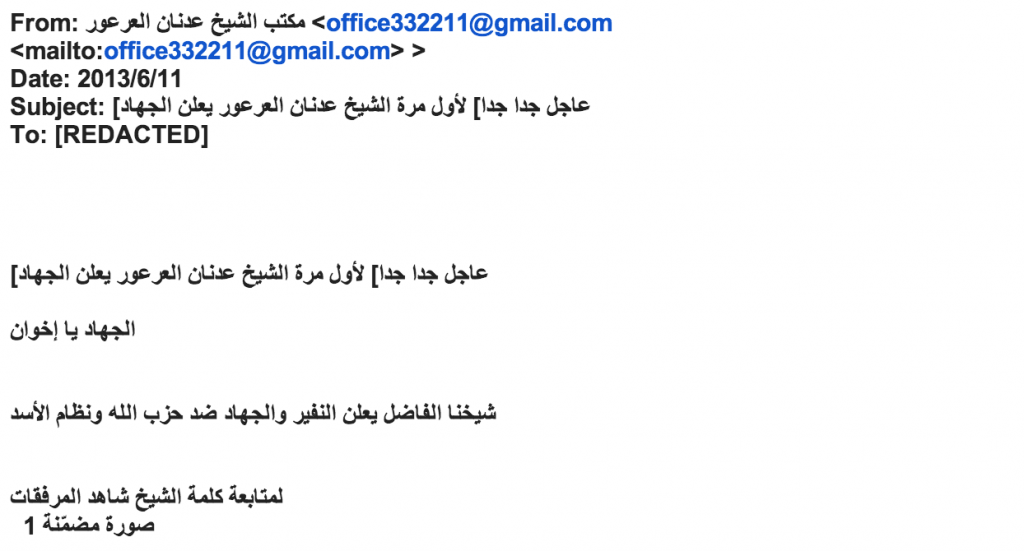

The potential victim in this attack first receives a message from an unknown source, in this case, a Gmail account with a nondescript name.

Example e-mail:

The e-mail contains text, an image (not shown), and an attachment. The text refers to a video of Sheikh Adnan al-Arour—a Sunni pro-opposition cleric—based in Saudi Arabia, calling for holy war against Assad and Hezbollah. The user is led to believe that opening the zip file, which is descriptively titled as being the Sheikh’s opinion, will provide access to the video.

While we have identified multiple different attacks with different zip files, the structure of all of these is consistent with the example described here.

Example zip files:

The zip file extracts to a Windows Shortcut file with the same name and a .lnk extension.

Example .lnk file “Sample A”:

Parsing these files reveals a URL embedded in the the file (bolded below).

Parsing Sample A:

When the victim executes the Windows shortcut, they are directed to one of several malicious links depending on the zipfile that they were sent. These are visible in the link parsing.

Links embedded in the Windows shortcut:

The victim is then shown either a YouTube video featuring Sheikh Adnan al-Arour, or a story on http://www.alkalimaonline.com, a Lebanese news site.

Example of YouTube video shown to victim:

The Malware

While the victim sees the decoy YouTube video or news website, a php file (g.php) that contains a hex-encoded malicious binary is fetched.

Excerpt from G.php:10

Once extracted, the binary11 of “Sample A” has the following properties:

The malware also adds a registry key to make it persistent across reboots:

The malware contains strings referring to “Data Protector v2” which appears to refer a crypter that is compatible with a range of RATs and advertised for download in a number of forums.12

Command and Control

Once the malware is successfully installed on the victim’s computer, it communicates with a C2 server at: tn5.linkpc.net

On June 11, this pointed to the following SyriaTel address:

This domain has been active since at least October 2012 and has pointed to many different addresses in Syrian IP space on both the SyriaTel and Tarassul ISPs, as well as AnchorFree VPN addresses.

The malware attempts to download a remote file called “123.functions”:

It was not possible to retrieve the remote file at the time of analysis, however, this behavior has been previously observed in malware targeting the Syrian opposition used to implant Xtreme RAT.

Conclusions

As the conflict in Syria drags on, digital campaigns targeting Syrian opposition have persisted. We have chosen to highlight two attacks that are part of recent efforts by Pro-Government Electronic Actors to compromise opposition communications and steal their secrets.

These attacks cater to the opposition’s communication behaviors and tactics. They are indicative of a combination of prior intelligence about the opposition, and ingenuity in social engineering. For example, many in the Syrian opposition are now aware of the electronic threats they face and seek out tools to increase their communications security and privacy. Tools and information about security and communications are in constant circulation. Some of this material addresses well-defined vulnerabilities. We have observed a greater degree of care among many in the opposition when facing certain situations that were common attack modalities in 2012. As awareness grows and behavior evolves, we suspect that some of the attacks that we regularly observed in 2012 are much less successful today.

Some of the information and practices that are shared between users, however, are much less appropriate, even inadvertently dangerous. For example, many legitimate tools are shared via third party file sharing sites or over social media. This situation presents a rich variety of targets for attackers in which to seed malicious binaries and links masquerading as familiar or desirable tools.

We infer that from the point of view of these attackers, not all attacks need to have sophisticated malware in order to be successful enough to be worth doing. Yet, perhaps in response to the growing awareness of previous and often widely targeted attacks against the Syrian opposition, attackers continue to innovate and experiment with new techniques that blend social engineering with new attack styles. The experiments are sometimes clearly successful. For example, in the case of Attack 2, the Windows shortcut files were not conclusively identified as malicious by even savvy opposition members for an extended period of time.

We hope that this post will increase awareness of the two attacks among potential targets. In the meantime, users who have executed either the fake Freegate file or clicked on one of the Windows shortcut files should consider their computers and accounts compromised.

Appendix: Recommendations for FreeGate and FreeGate Users

The Freegate website is blocked in China (its primary target market), as is the case with other similar circumvention tools. To get around blocking, tools are often distributed between individuals, or through untrusted downloads from third party sites. This is an unfortunate vector for attackers to distribute malicious installers and bundles that also contain functional versions of the program. As demonstrated by our work on the Freegate malware, as well as the Green Simurgh case, these vulnerabilities are exploited with serious consequences for high-risk users.

We understand the resource constraints that developers of free security and circumvention software often face. As such, we propose two simple steps that Freegate could take to help mitigate the current and similar future threats.

-

1) Freegate should take steps to make their users aware of the threat.

We provided Freegate developers with details of the attack, copies of the malicious binary, and other details prior to publication. We would like to point them towards the example established by Green Simurgh, who promptly posted a multilingual warning to their website when a malicious repackaging of their tool was found to be targeting Syrian users. We have offered to help them translate any warning materials into Arabic. -

2) Freegate should implement by-default HTTPS on their website.

Currently, visitors to the Freegate website follow non-HTTPS links to an unencrypted download. We believe that this presents a clear risk for man-in-the-middle attacks. Most developers of similar anti-censorship, circumvention, and security tools have implemented this security measure. We encourage Freegate to follow suit.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to several anonymous Syrians who brought these malware samples to our attention.

Additional thanks to Bill Marczak, Byron Sonne, Adam Senft, and Ron Deibert.

Footnotes

1 State-Sponsored Malware, “Electronic Frontier Foundation,” https://www.eff.org/issues/state-sponsored-malware.

2 We notified Freegate on June 17, 2013.

3 MD5 b3e1c2e40be54fbc0f7921ea8ce807e2

SHA1 3f6436420e84ac96d9a3c93045c07cdadda8ec81

SHA256 3712907740045871eef218fea7292c9c017e64cbb56b193b93f1a1b80afe599d

4 MD5 8eda7dfa4ec4ac975bb12d2a3186bbeb

SHA1 b5c49bbbf7499a30110adc94480b3edbc8d6e92b

SHA256 829e137279f691e493c211108b62c8e15b079bd619ba19ad388450878e0585d0

5 It failed to execute with .NET 4.0 on Windows XP.

6 The implant is installed regardless of whether or not the victim completes the FreeGate installation process.

7 The file fg735p.exe matches the hash of a legitimate FreeGate installer.

MD5 b083418be502162a4e248faab363f1b9

SHA1 030937f008bc203198e3754b1b54bb6d8d72794b

SHA256 d6ded89b91cdcd5d9ad4f6453f38f04f11f608d8db77db09e7400cfd7bcecddf

8MD5 2ba789458781b1dfd7f34624c8410edb

SHA1 77fd62d8e630e74d637682b91d0952d48b7c52be

SHA256 80b3fa8113a89040048a87c63ab9d8117368f2579368f5ea5999b145c47c4490

9 MD5 59c6e0fa61d62a1f52b6092dc92a4aa7

SHA1 fce82013dbb9261db8b14451122fa889dfdba2e0

SHA256 71cb3e1007da3193c89a532b275cf539730b25bd63bcc5e912503ddd4bc9097f

10 MD5 61a26c391aa95084521f5c0f6f70b966

SHA1 bd901cf02778d5c76dfe7c2877d773baa5bae5a7

SHA256 2c7600e0e660b0788faf5f5de3c10ac257000a557278eba41d3e7ec6175f22fb

11 MD5 00cc589571fa6e078cb92b34ea2ee1cc

SHA1 bfe30069998c5e4c43f98f17538678074d02ca3d

SHA256 bcf32f82f0971c8984bb493f5473f0f417c203c0484c80a772ee1165a8c7675d

12 For example, see: http://undercrypter.blogspot.de/2013/03/blog-post.html.