In an effort to update Canada’s federal commercial privacy legislation, the Canadian government has introduced new consumer privacy protection legislation. Bill C-11: Digital Charter Implementation Act, 2020, and in particular the Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) that is part of the larger piece of legislation, would significantly reshape Canada’s federal commercial privacy requirements. The legislation has been designed to advance consumer interests, as opposed to being based upon human rights principles, and would transform the nature of consent by expanding the range of situations where consent isn’t required to obtain, use, or disclose personal information. More positively, if passed as drafted the legislation would better empower the Privacy Commissioner and create a tribunal which would be responsible for enforcing the Commissioner’s decisions, and could assign monetary penalties where appropriate. Entirely absent from the legislation, however, is a requirement that organizations truly behave more transparently. Nor does the legislation meaningfully enhance the current limited rules which enable individuals to access and correct their personal information that is held by organizations. The proposed legislation also fails to satisfactorily ensure that whistleblowers who come to the Privacy Commissioner would be adequately protected from retribution.

The Citizen Lab’s research over the past decade has shown that it is critical for organizations to be transparent about the ways in which they interact with government agencies when those agencies request data, and especially in the Canadian context given the dearth of public transparency or accountability about how regularly law enforcement or security agencies exercise their powers.1 Furthermore, it is imperative that Canadian organizations explain how regularly they are asked, or required, to censor or takedown content at either governmental or private organizations’ behest to assess the ramifications of takedown laws and regulations. Our work has also helped to shine a light into the troubling situation facing Canadians (as well as individuals around the world) who use Subject Access Requests (SARs) to lawfully compel organizations to disclose the information that organizations have collected about individuals, and how that information is subsequently used or disclosed.

Given our experiences we have specific recommendations for how any federal commercial privacy legislation must be amended to better protect individuals from the predations and power of private organizations. In making our recommendations we have chosen to focus almost exclusively on the Openness and Transparency, Access to and Amendment of Personal Information, and Whistleblower sections of Bill C-11. We acknowledge the serious concerns pertaining to numerous sections of the proposed legislation, including those addressing meaningful consent, de-identification, and data mobility, but set these aside to focus on what have been less discussed elements of the legislation to date.

Background

Canadian policy makers, academics, and parliamentarians have been debating and assessing the relative strengths and deficiencies of Canada’s commercial federal privacy legislation for two decades. The Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) came into force in 2001 and has provided guidance for how organizations can collect, use, and disclose the personal information which is collected in the course of an organization’s operations. PIPEDA provides some assurances to Canadians and residents of Canada that there are rules about how organizations should treat the data under their control, while also ensuring that Canadian organizations can lawfully collect, process, and disclose European citizens’ data in the course of commercial operations.

Many of the issues that have surrounded PIPEDA since its inception have never been adequately remedied through subsequent legislation. Scholarly articles and consultations by the federal Privacy Commissioner have made plain that securing consent from individuals has remained a contentious problem, that the actual ‘teeth’ of the legislation remain in question both domestically and extraterritorially, and that questions of how to manage novel technologies under the principles of the commercial privacy legislation remain contentious. Moreover, the very nature of the Commissioner as an ombudsperson, auditor, consultant, educator, and regulator has sometimes made it difficult to know how these roles should be balanced, and has led to repeated calls to modify the powers and status of the Commissioner.

All of the aforementioned issues have, of course, been amplified as organizations have integrated digital technologies into their operations. The Commissioner’s inability to levy fines or compel organizations to modify their behaviours has meant that powerful companies such as Facebook have sometimes simply declined to modify their behaviours when found to be non-compliant with Canadian law. Compounding matters, businesses are increasingly voracious consumers of personal information as they seek to leverage machine learning, artificial intelligence, automated decision making, and other data-intensive processes to discover business efficiencies, advance their research and development activities, and secure ever greater profits. Basic principles of privacy protection, such as the idea that individuals ought to be able to meaningfully consent to having their information collected, used, or disclosed are increasingly seen as passé by some on grounds that historical transparency and consent mechanisms have failed consumers. Instead, some stakeholders claim that individuals should just expect that certain kinds of data are being collected, and individuals should only be notified in a specifically delimited set of circumstances and, more often than not, at precisely the moment when the organization wants to collect, process, or disclose the individual’s data.

For the past two decades, Citizen Lab researchers have sought to understand the relationship between how private organizations collect, process, and disclose personal information, and the ways in which individuals can assess or evaluate these organizational processes. Some of our investigations, such as those into telecommunications companies, fitness tracker companies, online dating services, and Chinese social media companies, have adopted a mixed methods approach. This approach entails:

- Using a semi-structured assessment criteria to assess organizations’ privacy policies and terms of service, as well as organizations’ law enforcement guidebooks2 and transparency reports 3 when they are available;

- Filing Subject Access Requests (SARs) under PIPEDA to the organizations; and

- Conducting technical analyses of organizations’ products and services.

Together these methods have let us triangulate how organizations publicly claim they handle personal information, how they implement those public claims when responding to SARs, and how they actually handle information in designing their products or services.

All of the Citizen Lab’s projects which assess organizational transparency operate with the assumption that for individuals to take control, or understand, how their personal information is used an organization must clearly explain its practices in open and accessible policy documentation. This documentation, in turn, should parallel how organizations actually behave when responding to user requests and how they have designed their products and services. Unfortunately, our research has routinely revealed that organizations’ public policy documents infrequently align with the information provided to law enforcement organizations, or with the information that is actually collected, used, or disclosed based on our technical analyses of organizations’ products. Further, individuals who file SARs under PIPEDA cannot expect fulsome responses when issued to organizations with a substantial commercial connection to Canada or Canadians.

The CPPA is, in theory, intended to clarify the information that organizations must publicly disclose in policy documentation. Similarly, the legislation has been cast as expanding upon the kinds of information that individuals should receive when they file SARs. Based on our assessment of the CPPA, and experiences in exercising our rights under PIPEDA, we do not believe that the proposed legislation will meaningfully address existing limitations pertaining to accessing and correcting personal information, nor will it compel Canadian organizations to adopt contemporary best transparency practices. Worse, without strengthening protections provided to whistleblowers any member of an organization who suspects their organization of misusing personal information may be reticent to come forward with what they know.

Organizational Openness and Transparency

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada’s (OPC) guidance makes clear that, to obtain meaningful consent under PIPEDA, organizations must bring the following elements of their organizational practices to individuals’ attention:

- What personal information is being collected, with sufficient precision for individuals to meaningfully understand what they are consenting to;

- With which parties personal information is being shared;

- For what purposes personal information is being collected, used or disclosed, in sufficient detail for individuals to meaningfully understand what they are consenting to; and

- What are the risks of harm and other consequences.

Furthermore, under PIPEDA’s guidance on Openness, even where organizations are not required to first obtain consent before transferring information to third-parties, they are “nonetheless required to make every reasonable effort to inform individuals about the transfer.”

Despite the OPC’s guidance that, “[i]ndividuals should not be expected to decipher complex legal language in order to make informed decisions on whether or not to provide consent”, our research, as well as that of other academics, has shown that this information is routinely isolated to privacy policies and terms of service, and tends to be challenging for even experts to decipher.

To give an example: in assessing how fitness tracker companies collect, use, or disclose personal information, we found that privacy policies routinely failed to differentiate between the data collected by the hardware trackers that were worn, the corresponding smartphone application, and a company’s website or other services that were offered. Moreover, some companies failed to provide clear timelines for which data was retained,4 highly variable interpretations of what constituted personal information,5 or with whom, precisely, data was disclosed to and under what conditions.6

Similarly, research that explored how long and for what reasons Canadian telecommunications companies collect, retain, and disclose personal information led to unsatisfactory conclusions.7 Our research demonstrated that companies’ public facing documents rarely, as examples, explained the specific period of time for which location data was collected or the specific conditions under which it could be used. As a result, individuals could not understand, in practice, just how their personal information was collected, used, or disclosed by some of the oldest, best capitalized, heavily regulated, and technically savvy organizations operating in Canada.

Our assessments of social media companies has, similarly, revealed there is often a difference between what an organization publicly asserts versus what it does with Canadian users’ data. A 2020 Citizen Lab report used technical methods to demonstrate that Canadians who signed up for WeChat, a Chinese social media service, had their communications placed under surveillance by the company so that it could develop the censorship index that the organization applies to individuals who sign up for WeChat either within China or using a Chinese phone number. We subsequently conducted a policy analysis; at no point in this analysis could we find any clear language explanation that warned users that such surveillance would be conducted.

The CPPA’s current drafting does not require organizations to adopt public facing language that will improve upon the current state of affairs. Instead, the legislation would require organizations to provide descriptions of the “type of personal information under the organization’s control” and for “general” accounts of how organizations make use of personal information or how an organization uses automated decision systems to conduct actions which could significantly impact individuals. While an organization may, per 15(3)(e), identify the other organizations with which they disclose personal information in public facing documents such as privacy policies or terms or service agreements before obtaining an individual’s consent, they may also present that information as an individual is in the process of signing up for a service. This latter approach would have the effect of requiring individuals to begin to sign up to a service before they could learn with whom their personal information may be disclosed.

As drafted, many of the aforementioned deficient behaviours might be conducted by an organization. Fitness tracker companies might blithely refer to ‘business operations’ to justify the retention of information, without clearly describing what those operations entail. Telecommunications companies might provide only general accounts of the types of information they collect, comprehensively across the entirety of their organizations, as opposed to detailed accounts of what information was collected per service used, and for how long it is stored and for what purposes it is specifically used or disclosed to others. And companies could continue including language that prevents individuals from understanding when their information is used or disclosed for a specific purpose as opposed to when it may be used or disclosed for a general class of purposes or to a general class of recipients (e.g., “to business partners”).

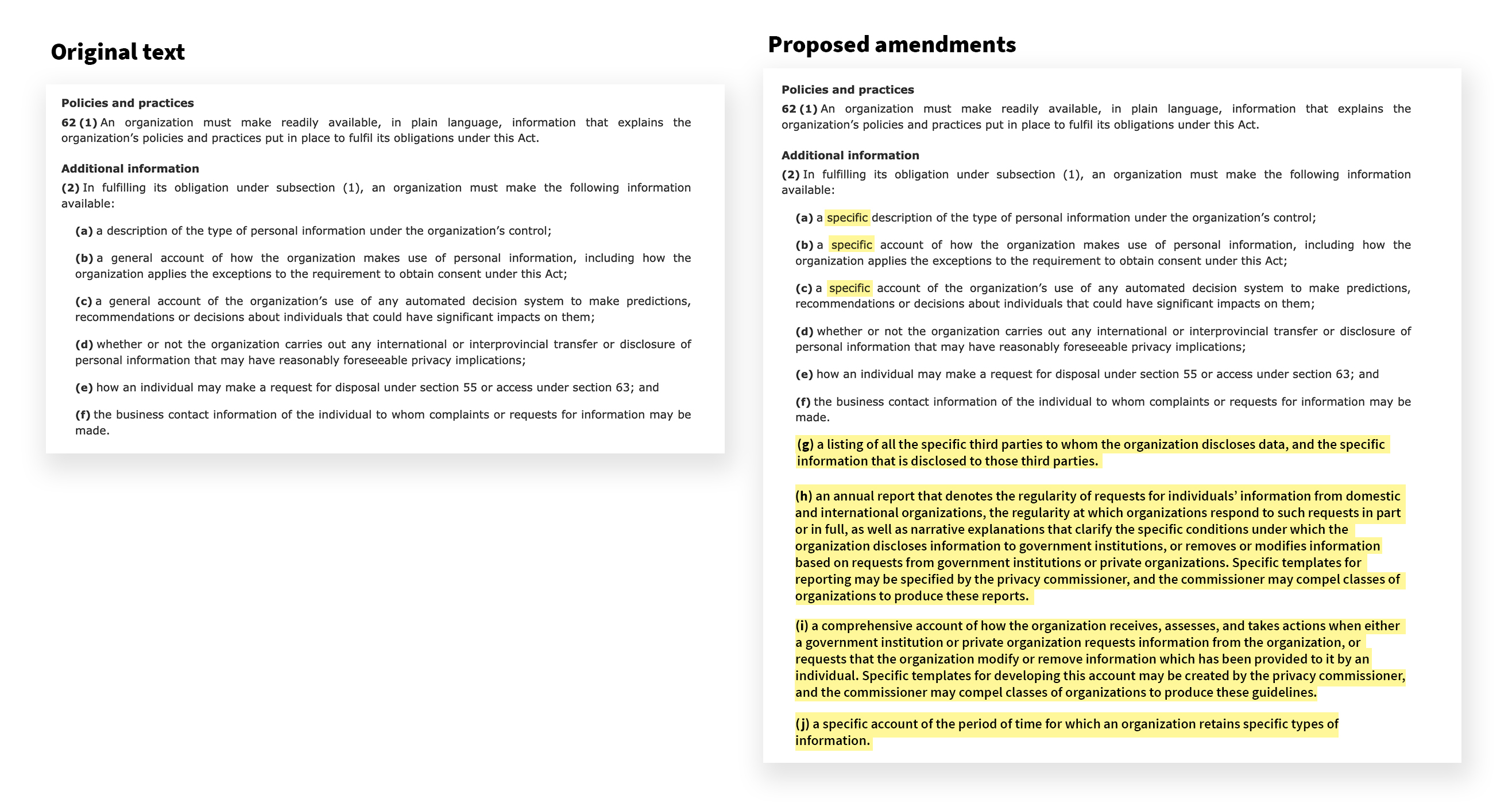

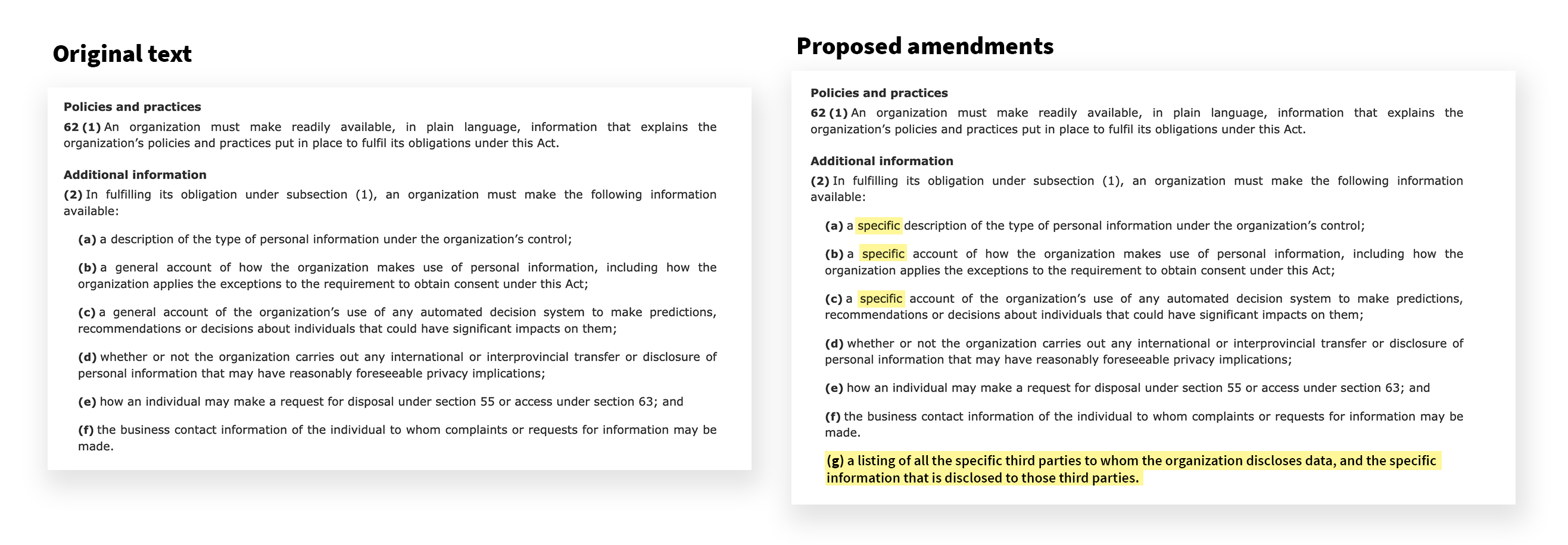

As a result, we recommend that the legislation make clear that specific information must be included in publicly available explanations of organizations’ collection, use, and disclosure of personal information. 62(2)(a), as an example, might be amended to begin “a specific description of…”, 62(2)(b), “a specific account of…” and 62(2)(c), “a specific account of…”.

We also recommend adding 62(2)(g), which would read: “a listing of all the specific third parties to whom the organization discloses data, and the specific information that is disclosed to those third parties.”

Furthermore, Internet and telecommunications companies that adhere to best business practices currently publish annual transparency reports that denote the frequency and rationale for which government agencies have made requests for personal information in the respective organizations’ control, as well as publishing up-to-date government law enforcement guides. The benefit of both of these practices is that it makes clear to individuals how government agencies may lawfully collect information and how organizations manage the personal information they are entrusted to handle.

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) published voluntary transparency reporting guidelines for Canadian companies in 2015 so that the companies can present information to the public in ways that do not jeopardize government investigations. Some telecommunications companies have adopted those guidelines, with some minor modifications, but most Canadian companies have declined to adopt these voluntary guidelines. Other telecommunications companies such as Bell Canada have never released a transparency report, and other companies such as Acanac and Sasktel have ceased publishing annual reports.

We recommend that organizations be required to publish transparency guides by adding 62(2)(h): “an annual report that denotes the regularity of requests for individuals’ information from domestic and international organizations, the regularity at which organizations respond to such requests in part or in full, as well as narrative explanations that clarify the specific conditions under which the organization discloses information to government institutions, or removes or modifies information based on requests from government institutions or private organizations. Specific templates for reporting may be specified by the privacy commissioner, and the commissioner may compel classes of organizations to produce these reports.”

Similarly, organizations should be required to publish how they have, or will, interact with domestic and international government institutions and private organizations that request or demand access to personal information in an organization’s care or for the modification or removal of information that the organization has had a role in publishing. Current language that is included in privacy policies and terms of service rarely, if ever, clearly explain the processes that organizations have for intaking and confirming the validity of such requests, nor conditions under which they will fully or partially respond to such requests.8

We recommend that organizations be required to develop and publish law enforcement guidelines, by adding 62(2)(i): “a comprehensive account of how the organization receives, assesses, and takes actions when either a government institution or private organization requests information from the organization, or requests that the organization modify or remove information which has been provided to it by an individual. Specific templates for developing this account may be created by the privacy commissioner, and the commissioner may compel classes of organizations to produce these guidelines.”

With regards to aforementioned two recommendations, we recognize that it may be appropriate to apply such requirements only to organizations of a certain class or market size, or require organizations to produce a guide after having received their first request from a government institution for personal data under the organization’s control or after being compelled by the privacy commissioner to produce them. Regulations could specify the kinds of information that must minimally be included in law enforcement guides that pertain to laws or regulations that different industry categories are most likely to have applied to them.

Finally, individuals may only learn about how long an organization retains their personal information after they have signed up for an organization’s service and submitted a subject access request for their information. Such information should be included in public facing documentation. As such, we recommend that organizations be required to prepare and publish data retention schedules that identify the specific types of information organizations collect, the period of time for which they retain the identified information, and to whom information is disclosed. This requirement could be included at 62(2): “(j) a specific account of the period of time for which an organization retains specific types of information.” (See Figure 2)

Access to and Amendment of Personal Information

The practice of accessing and correcting the personal information that an organization possesses about oneself is centrally about confirming or understanding an organization’s data handling practices. The ability to undertake such actions is of heightened importance given the challenges in understanding how an organization collects and handles personal information based only on publicly-available organizational documentation; SARs ostensibly offer a way to ‘lift the lid’ on what an organization is really doing when collecting, using, or disclosing personal information.

Citizen Lab researchers and their affiliates have used SARs to obtain access to researchers’ own personal data as part of successive research projects. Throughout our efforts in testing this element of PIPEDA, however, we have found at least two classes of problems that should be addressed in the CPPA: issues that precede requests and issues that arise during requests.

As drafted, the CPPA does not require organizations to identify to whom they have specifically disclosed information; while organizations may do so, they are also permitted to “provide to the individual the … types of parties to which disclosure was made”. Based on our research we expect this will prevent individuals from knowing with whom their information has actually been disclosed and, as such, prevent individuals from issuing SARs to organizations that have had the individual’s information disclosed to them. Fundamentally, this will mean that individuals will be unable to ascertain which organizations have received their information, and subsequently understand why these organizations collected, used, or further disclosed the information.

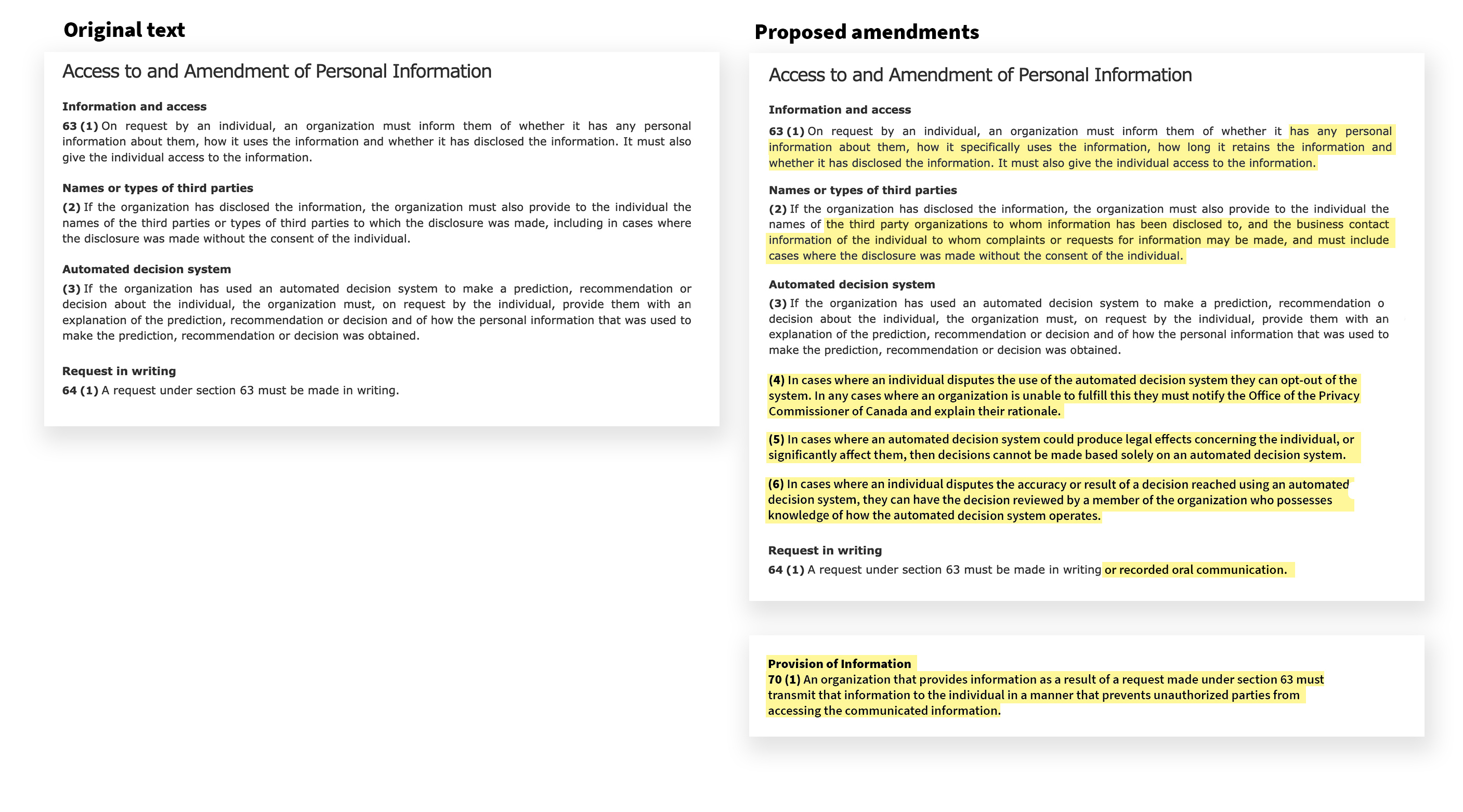

Thus, we recommend that 63(2) be amended as, “If the organization has disclosed the information, the organization must also provide to the individual the names of the third party organizations to whom information has been disclosed to, and the business contact information of the individual to whom complaints or requests for information may be made, and must include cases where the disclosure was made without the consent of the individual.”

In the process of fulfilling requests, organizations often fail to provide information about data use, retention, and disclosure schedules, make clear to whom information is disclosed, what the information provided to requesters means, and routinely transmit SAR responses over insecure communications channels.

Organizations should be required to provide full data use, retention, and disclosure schedules to individuals who issue a SAR. Such schedules should specify the precise information that has been collected, as opposed to specify general types of information that have been collected. Furthermore, organizations should be required to specify precisely how they use the information. We recommend that 63(1) be amended to include: “…has any personal information about them, how it specifically uses the information, how long it retains the information and whether it has disclosed…”.

As noted previously, the organizations may use automated decision systems in processing personal information, to the effect of making a prediction, recommendation, or decision about an individual. The CPPA does not, however, provide individuals with a right to object to how an automated decision system is used, nor require that a member of the organization employing the automated decision be involved in assessing automated decisions that may have legal consequences for the affected person. Finally, the CPPA does not require that decisions ultimately be reviewed by a member of the organizations employing the automated system.

We recommend that 63(4) be created, to read, “In cases where an individual disputes the use of the automated decision system they can opt-out of the system. In any cases where an organization is unable to fulfill this they must notify the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada and explain their rationale.”

We also recommend that 63(5) be created, to read, “In cases where an automated decision system could produce legal effects concerning the individual, or significantly affect them, then decisions cannot be made based solely on an automated decision system.”

Furthermore, we recommend the creation of 63(6), to read, “In cases where an individual disputes the accuracy or result of a decision reached using an automated decision system, they can have the decision reviewed by a member of the organization who possesses knowledge of how the automated decision system operates.”

Many organizations, including those in Canada, have adopted processes to enable customers to issue SARs when speaking with customer service representatives. While the Citizen Lab generally has recommended that individuals issue SARs in writing, we recognize that Canadians should be able to issue SARs to organizations in either writing or through oral requests.

We recommend that 64(1) be amended to, “A request under section 63 must be made in writing or recorded oral communication.”

In our research, we have found that organizations do not necessarily provide information that is requested by individuals using secure communications formats. The potential result is that individuals’ personal information may be put at risk by organizations responding to SARs.

We recommend that organizations that respond to a SAR be required to provide responses to individuals using secure communications channels. A new section could be added after 69, entitled “Provision of Information” and the (new) 70 read: “An organization that provides information as a result of a request made under section 63 must transmit that information to the individual in a manner that prevents unauthorized parties from accessing the communicated information.”

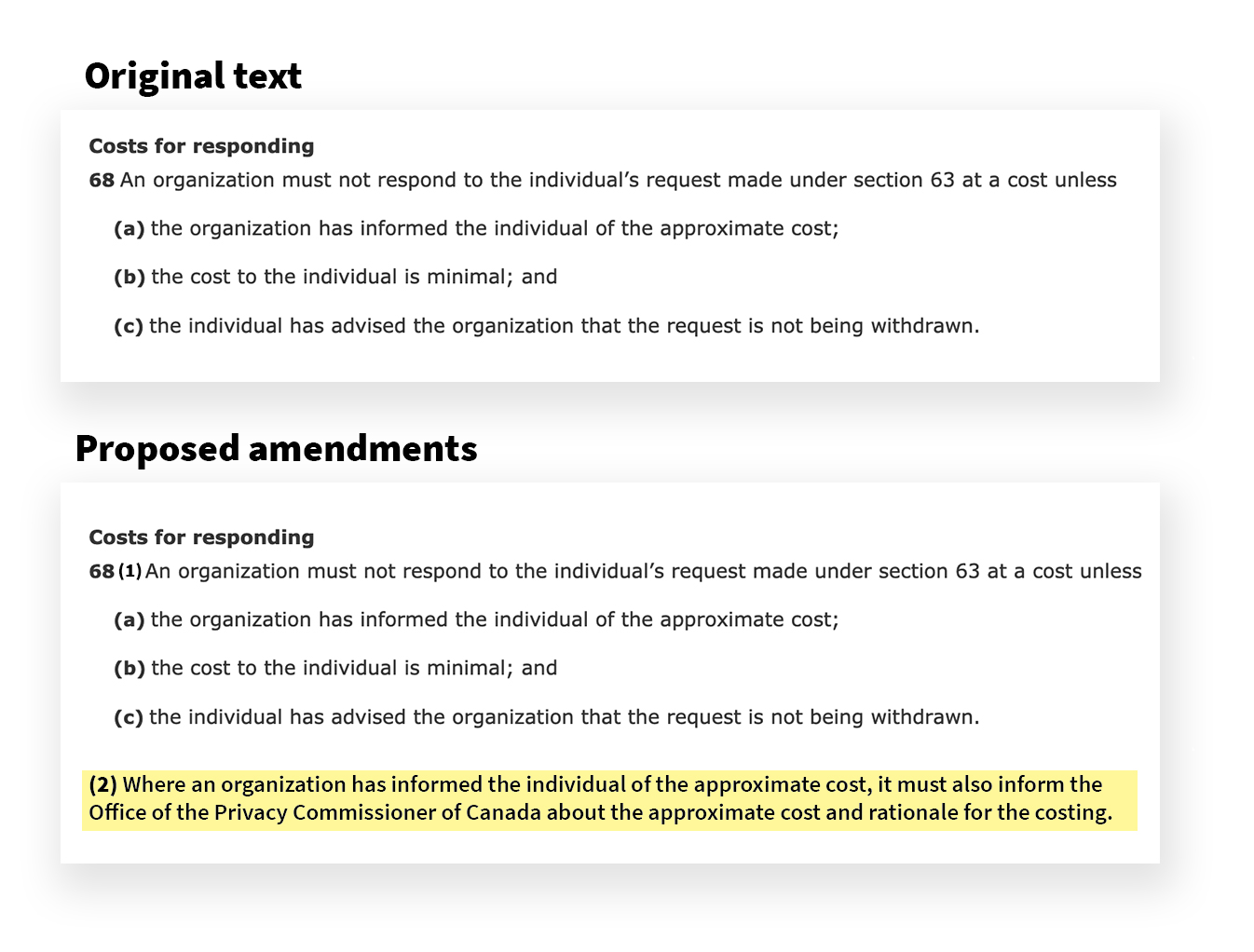

Based on our experiences using PIPEDA to file SARs, we have found that some types of industries demand individuals pay incredibly high fees before processing the request. To provide examples, Rogers has previously required Citizen Lab researchers to pay in excess of $900 before fulfilling a request, and another smaller Canadian telecommunications company demanded $1,200 before it would fulfill a request for the information the company had collected, used, or disclosed. Presently, negotiations about fees are left mostly to individuals and, when facing these kinds of fees, cause individuals to regularly terminate their request without receiving data. While some individuals may appeal fee demands to the OPC, this occurs infrequently.

The OPC would be better situated to launch their own evaluations of fee demands or realize that guidance is needed should the Commissioner realize that certain classes of organizations were demanding high fees, arguably in violation of 68(b) of the CPPA. As such, any time an organization demands a fee be paid prior to disclosing information to a requester, it should be required to notify the OPC of the fee demand and the breadth of the request. Doing so would meet a public good by providing information to the OPC so that it can better enforce provisions of the CPPA. Specifically, we recommend that the CPPA should be amended to include, “68(2): Where an organization has informed the individual of the approximate cost, it must also inform the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada about the approximate cost and rationale for the costing.”

Whistleblowing

Whistleblowing is important in our societies, as it enables employees to report on potentially unlawful collections, uses, or disclosures of personal information. There is a clear public interest in encouraging individuals to follow in the footsteps of the whistleblowers that brought Cambridge Analytica, as an example, to the Canadian public’s attention.

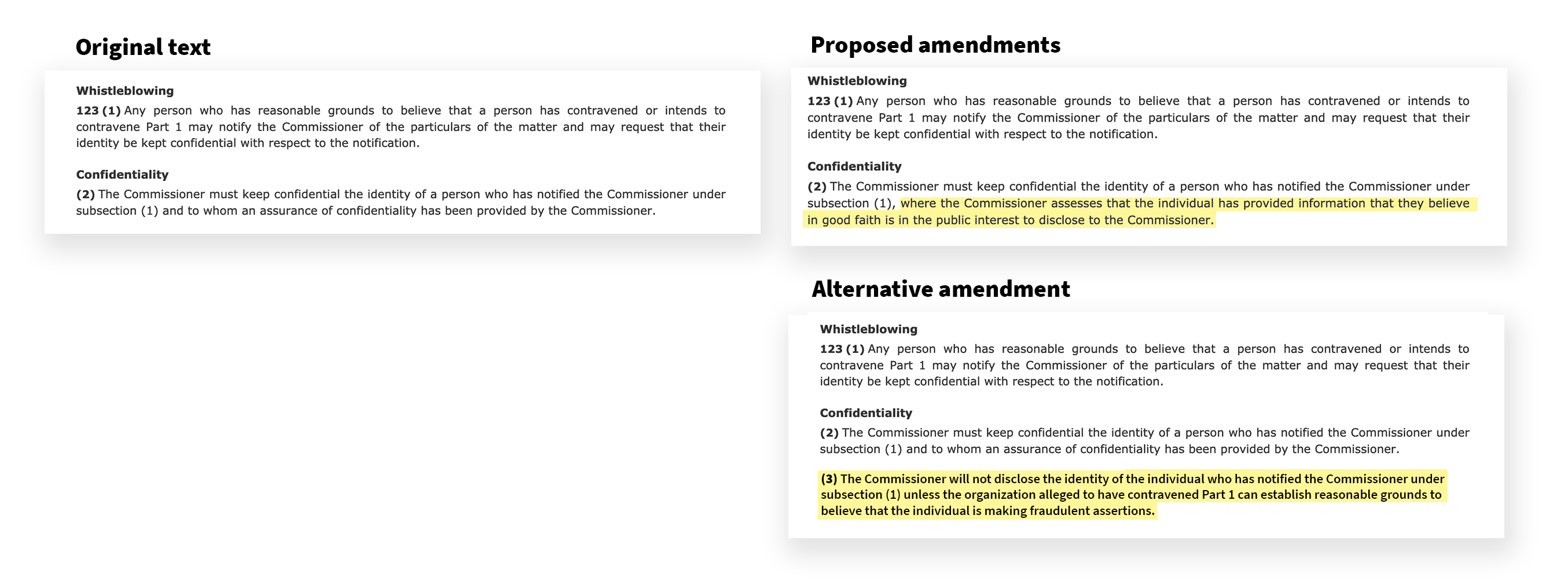

The existing whistleblowing section in the CPPA, however, does not make clear to whistleblowers that their disclosures will necessarily be treated with confidentiality. As presently drafted, a whistleblower’s confidentiality is only assured after they have disclosed information to the Privacy Commissioner and the Commissioner has issued an assurance of confidentiality. Consequently, whistleblowers may decline to disclose information to the Commissioner on the basis of being uncertain about the consequences of engaging with the Commissioner: will the Privacy Commissioner provide the assurance of confidentiality, or may the Commissioner instead report the whistleblower’s activity to the organization against whom they are blowing the whistle?

To provide further confidence to whistleblowers, and clarity in how the Commissioner will interact with whistleblowers, we recommend that 123(2) be amended to, “The Commissioner must keep confidential the identity of a person who has notified the Commissioner under subsection (1), where the Commissioner assesses that the individual has provided information that they believe in good faith is in the public interest to disclose to the Commissioner.”

Alternatively, the legislation might be amended to provide assurance to whistleblowers by delimiting the Commissioner’s discretion to alert organizations that the whistle has been blown about an organization’s activities. Should this approach be preferred, then we recommend the CPPA be amended to include 123(3), “The Commissioner will not disclose the identity of the individual who has notified the Commissioner under subsection (1) unless the organization alleged to have contravened Part 1 can establish reasonable grounds to believe that the individual is making fraudulent assertions.”

Conclusion

Canada’s federal commercial privacy legislation desperately needs to be updated so that organizations better understand their responsibilities in handling personal information, and so that Canadians and residents of Canada can take comfort in knowing that organizations are subject to robust legislation designed to protect their personal information. Others have rightly pointed out that the CPPA raises considerable concerns about its ability to adequately protect individuals’ interests when it comes to addressing meaningful consent, de-identification, or data mobility, and the Citizen Lab’s own narrow analysis of the legislation has revealed serious shortcomings concerning how organizations are to be transparent about their data handling practices or how they will be required to manage subject access requests. And, should members of an organization suspect malfeasance in how their organization handles data, they may be reluctant to become whistleblowers based on the way the CPPA would protect them.

As it is presently drafted, the CPPA inadequately protects Canadian citizens’ and residents of Canada’s interests and, as such, will weaken trust in how organizations handle personal information. Beyond the specific amendments and recommendations that we have made to the CPPA we strongly believe that the government must reconsider the very underlying philosophy of the legislation, and transform the bill from being focused on protecting consumer rights to protecting Canadians’ human rights. Only after this broader conceptual shift takes place can legislation be drafted to comprehensively account for the interests of Canadians in keeping their personal information safe, secure, and only used in transparent and agreed upon ways. Pursuing the current course of action is foolhardy, will fail to actually better protect consumers, and will inadequately protect Canadians from the predations of private organizations. Despite being consumer protections-oriented legislation, consumers will not be adequately protected should it be passed into law in its current format.

- Parsons, Christopher. (2020). “Electronic Surveillance: The Growth of Digitally-Enabled Surveillance and Atrophy of Accountability,” in Harold Jansen and Tamara Small (Eds.), Digital Politics in Canada; Parsons, Christopher; and Molnar, Adam. (2021). “Horizontal Accountability and Signals Intelligence: Lesson Drawing from Annual Electronic Surveillance Reports,” David Murakami Wood and David Lyon (Eds.), Big Data Surveillance and Security Intelligence: The Canadian Case.

- Guidebooks explain to law enforcement agencies, as well as the public, how organizations respond to requests for information from government organizations. These documents routinely explain the kinds of data an organization collects, uses, and discloses, as well as the period of time such data is retained and the legal powers required to lawfully compel the organization to disclose the data to government agencies. For a Canadian example, see: https://www.teksavvy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Law-Enforcement-Guide-2017-10-30.pdf.

- Transparency reports are published by organizations and disclose the regularity at which government agencies make requests for data under the organization’s control, the kinds of legal powers exercised in requesting data, and the regularity at which an organization has disclosed data in response to lawful orders from government agencies.

- e.g. Garmin stated it would store data as long as “necessary to fulfill the purposes outlined in the Privacy Statement unless a longer retention period is required or permitted by law.” See: https://openeffect.ca/reports/Every_Step_You_Fake.pdf.

- Xiaomi explicitly stated that fitness tracker information constituted personally identifiable information (PII) and gave an extensive list of other data that is PII, such as email address, phone number, mobile device identifiers (e.g. IMEI), location information, and physical characteristics (e.g. age, weight, height, gender). More generally, companies maintained that information that relates to an identified or identifiable person constitutes PII. As examples, for Fitbit, “data that could reasonably be linked back to you” was PII, for Garmin it was “information that identifies a particular individual”, and for Basis information that the user provided to the company is PII. For many companies, fitness information such as distance walked, types of exercise, and location data were not classified as personal information. For more, see: See: https://openeffect.ca/reports/Every_Step_You_Fake.pdf.

- Rather than naming specific partners, organizations routinely stated they would share information to complete business processes without naming specific processes, or otherwise disclose information as obligated under a law or regulation or at the company’s discretion.

- See: http://www.telecomtransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Governance-of-Telecommunications-Surveillance-Final.pdf at pp. 48-54.

- Organizations may sometimes only partially respond due to a request being overbroad, an organization not possessing all of the information requested, or because the request or demand has not properly cited law which would authorize the organization to disclose or modify the information in question.