Key findings

- We analyze the system Amazon deploys on the US “amazon.com” storefront to restrict shipments of certain products to specific regions. We found 17,050 products that Amazon restricted from being shipped to at least one world region.

- While many of the shipping restrictions are related to regulations involving WiFi, car seats, and other heavily regulated product categories, the most common product category restricted by Amazon in our study was books.

- Banned books were largely related to LGBTIQ, the occult, erotica, Christianity, and health and wellness. The regions affected by this censorship were the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and many other Middle Eastern countries as well as Brunei Darussalam, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles, and Zambia. In our test sample, Amazon censored over 1.1% of the books sold on amazon.com in at least one of these regions.

- We identified three major censorship blocklists which Amazon assigns to different regions. In numerous cases, the resulting censorship is either overly broad or miscategorized. Examples include the restriction of books relating to breast cancer, recipe books invoking “food porn” euphemisms, Nietzsche’s Gay Science, and “rainbow” Mentos candy.

- To justify why restricted products cannot be shipped, Amazon uses varying error messages such as by conveying that an item is temporarily out of stock. In misleading its customers and censoring books, Amazon is violating its public commitments to both LGBTIQ and more broadly human rights.

- We conclude our report by providing Amazon multiple recommendations to address concerns raised by our work.

Introduction

The rise in online shopping has led to more global reach into markets that may otherwise be inaccessible for companies through traditional retail channels. This increased reach brings new opportunities but also has its own challenges for global e-commerce retailers. One such challenge is in dealing with different, more restrictive regulatory environments worldwide.

In this report, we analyze American e-commerce retailer Amazon and its system for preventing shipments of certain products to certain world regions as it is implemented on the US storefront — amazon.com. Specifically, we analyze functionality that Amazon implements to restrict shipments of certain products to certain regions even if the product is available and sellers are offering to ship it there. While Amazon normally hides this restriction system from customers using misleading error messages, we employ a novel methodology to uncover and measure on which products and in which regions it is activated by peeling back the layers of Amazon’s website and analyzing its internal workings. Notably, our method can distinguish between a product being restricted by Amazon and it being organically unavailable in a region.

In total, we found 17,050 products that were restricted from being shipped to at least one world region. While many of the shipping restrictions observed in our study are related to regulations involving WiFi, car seats, and other heavily regulated product categories, the most common product category restricted by Amazon was books. Banned books were largely related to LGBTIQ, the occult, erotica, Christianity, and health and wellness. More broadly, books were the victims of censorship, which in this report we define as Amazon’s restriction of product shipment under political or religious motivation. The regions commonly affected by this censorship were the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and many other Middle Eastern countries as well as Brunei Darussalam, Papua New Guinea, Seychelles, and Zambia.

Given that the topics censored include LGBTIQ, our findings call into question Amazon’s public commitment to LGBTIQ rights as well as its respect for the rights of its users at large. By censoring the availability of books, Amazon is depriving its users of valuable information. Furthermore, by communicating to customers that censored products are organically unavailable (e.g., being out of stock), Amazon is depriving customers of the ability to make informed decisions. We conclude our report by making multiple recommendations to Amazon.

Background

In this section we briefly describe Amazon’s history as it relates to our analysis. We then outline some of the regulations applying to Amazon’s business in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and China, which are some of the more restrictive regulatory environments to which products on amazon.com can be shipped.

Amazon background

Amazon is an American multinational company that originated as an online bookseller and has since evolved into a global e-commerce marketplace. Amazon’s business is heavily focused on managing shipping logistics internationally and serving a global consumer base. Alongside the main e-commerce platform, they also provide cloud computing services (Amazon Web Services), consumer electronics (Amazon Kindle and Amazon Echo), and online streaming (Amazon Prime Video) among other offerings.

Amazon is best known for its original website — amazon.com — which serves as the landing page for US customers, although items can be shipped globally depending on seller preferences. As of 2024, there are dedicated storefronts for 22 other regions. Alongside the online expansions to other regions there has been an analogous expansion of physical infrastructure in those regions including shipping hubs, fulfillment centers, sorting facilities, and delivery stations.

Most relevant to our study, Amazon has expanded its dedicated storefronts to include the UAE in 2017 and Saudi Arabia in 2020. This expansion included opening a regional headquarters in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, in 2022 and a fulfillment center in Dubai, the UAE, in 2023. These recent expansions into the Middle East create their own unique challenges to the retailer because of the region’s distinct regulatory regimes, which we detail below.

Compliance with international regulations

Amazon polices the products sold on its platform, and their own shipping restrictions FAQ provides some guidance on why certain products may be restricted, including the need to “comply with all laws and regulations and with Amazon policies” and that Amazon may be “restricted from shipping to your location due to government import/export requirements, manufacturer restrictions, or warranty issues”. Amazon has adapted its policies to allow for the removal of offensive content including content that Amazon determines is “hate speech, promotes the abuse or sexual exploitation of children, contains pornography, glorifies rape or pedophilia, advocates terrorism”, but also “other material [they] deem inappropriate or offensive”. However, Amazon has failed to reveal specifically what categories of content it restricts to comply with the demands of authoritarian governments.

There have been reported incidences where Amazon complied with governments’ requests to restrict certain products or even go as far as manipulate its reviews. For example, Amazon restricted items for purchase and in search results relating to over 150 keywords relating to LGBTIQ content in the UAE after receiving pressure from the government to remove them. In China, Amazon removed all customer ratings and reviews for a book of Chinese president Xi Jinping’s speeches and writings. In both instances, Amazon claimed that they were following local laws and regulations. However, in India, internal Amazon documents showed that Amazon was circumventing local regulations by providing preferential treatment to certain sellers and by also promoting its own merchandise by rigging search results. Amazon has also been criticized for allowing its platform to spread white supremacy and racism. Items with Nazi symbols and Kindle books associated with neo-Nazis and white supremacists have remained widely available despite Amazon having been notified by journalists and non-profit organizations.

Regulations in Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, content is largely governed by two laws: the 2003 Law of Printing and Publication, largely regulating print media, and the 2007 Anti-Cyber Crimes Law, regulating online media. Article 9 of the Law of Printing and Publications states that printed media cannot contravene Sharia Law, stir up internal discord, injure the economic and health situation of the country, or lead to a breach of either public security, public policy, or foreign interests. Article 18 states these regulations should apply to the importation and distribution of printed materials. An approval is required, within the framework of Article 18 of the Printing and Publication law, in order to certify that content is free from any content that is insulting to Islam, the government, interests of the Emirates, or ethical standard and public morality. In terms of enforcement, Article 39 states that any contravening printed items can be withdrawn from circulation if they are found to violate either Articles 9 or 18.

The 2007 Anti-Cyber Crimes Law is chiefly focused on regulations around information security and content regulation. Article 6 of this law states that “production, preparation, transmission, or storage of material impinging on public order, religious values, public morals, or privacy, through an information network or computer” is a criminal offense. Contravening this article can lead to a maximum punishment of five years in prison and a maximum fine of three million riyals (approximately 800,000 USD). This law has been applied against online content. For example, in 2019, Saudi Arabia alerted Netflix that an episode of Hasan Minhaj’s comedy show Patriot Act violated this statute as it contained criticism of a Saudi Arabian royal. Netflix complied with the government order and restricted access to the episode for Saudi Arabian users.

Regulations in the UAE

In the UAE, content is governed by the Federal Decree-Law No.55 of 2023 on Media Regulation, which replaced the previous Federal Law No.15 of 1980 Concerning Publications and Publishing. Specifically, it regulates print, television, as well as online media. Another relevant regulation is the Internet Access Management Regulatory Policy which focuses on the regulation of online content. Under this policy, the only two internet service providers (ISPs) in the UAE, Etisalat and Du, are required to block online content if requested by the Telecommunications and Digital Government Regulatory Authority. Prohibited Internet content includes pornography, contempt of religion, and promotion of or trading in prohibited commodities and services. Category 13 of the policy prohibits sites from promoting or trading in commodities prohibited or restricted by licenses in the UAE, including “prints, paintings, photographs, drawings, cards, books, magazines, and stone sculptures, which are contrary to the Islamic religion or public morals, or involving intent of corruption or sedition”.

Compliance with Chinese demands

In 2004, Amazon entered the Chinese market via its acquisition of Joyo, a Chinese online bookstore. Amazon faced scrutiny for its political censorship of products on its Chinese site — amazon.cn. However, facing competition from domestic rivals, Amazon terminated its online store in China in 2019, although for a limited time overseas products were still sold on the amazon.cn site. Amazon still has other operations in China, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), which is Amazon’s cloud computing service. Outside of China, in 2021, on the US Amazon storefront — amazon.com — Amazon partnered with China International Book Trading Corp, a state-owned firm that has been labeled as “China’s state propaganda arm”, to create a portal for selling books that amplify the Chinese Communist Party’s agenda.

Methodology

In this section, we explain how we determine product availability across different regions. Our methodology consists of two phases. As our original motivation was to understand how Amazon censorship applies to Middle Eastern countries, in our first phase, we focus on studying how products and shipment restrictions vary across multiple countries in the Middle East. We were particularly motivated to understand the differences between restrictions imposed on the shipment of products to Middle Eastern countries in which Amazon operates a storefront (namely, the UAE and Saudi Arabia) versus those in which it does not. To understand how censorship applies more broadly to the world at large, in our second phase we pivot from the results of the first phase and measure product availability in regions across the globe.

In designing our methodology, we were motivated by eliminating false positives, even if doing so might introduce false negatives. The rationale is that we would rather omit the measurement of some instances of censorship rather than falsely attribute censorship to products that are not censored.

In the remainder of this section we explain the two phases of our methodology.

Phase 1: Measuring censorship in Middle East

One way to try to measure Amazon censorship in Middle Eastern countries would be to visit those Amazon storefronts which are available in the Middle East, namely, the UAE’s amazon.ae or Saudi Arabia’s amazon.sa, and to try to determine which products are anomalously “missing” from being sold on these two Amazon sites. This approach, however, would be limited. For example, if we saw one book related to LGBTIQ topics that was sold on amazon.com but not amazon.ae, that might be due to the book being censored on amazon.ae, but another possibility is that the book was out of stock or not sufficiently popular to be sold in some countries. However, if we saw a disproportionately large number of books related to LGBTIQ topics that were available on amazon.com but not sold on amazon.ae, then we would have a stronger argument, but this argument would be at best a statistical argument, and for any individual product we would not be able to prove whether it was the victim of censorship or was unavailable on that storefront for some other reason.

Given the weakness of the previously described approach, we instead measured whether products on amazon.com, the American storefront, could be shipped to various countries. As an additional benefit, this approach allowed us to study censorship in regions that did not have their own dedicated storefront. For our investigation of censorship in the Middle East, we picked four Middle Eastern countries: the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Yemen. We also tested a fifth country, Canada, as a control, which we explain later in our methodology.

To test which products we could ship to these five countries, we required a method for sampling a sufficiently diverse set of Amazon products to test. To address this requirement, we made use of the Common Crawl data set provided by the Common Crawl Foundation. This data set is a diverse, open Internet-wide sample of Web pages scraped beginning in 2008. In April 2023, we downloaded all of the archives up to and including the February/March 2023 archive. To avoid excessive storage requirements of storing the entire data set, we downloaded the archive in streaming fashion, filtering out any Amazon product URL into a file without storing any other data from the data set. We processed the Common Crawl data from 2013 through March 2023, as March 2023 was the most recent data set available at the time that we began our testing. Although we were only interested in products available on the amazon.com storefront, since products are often available on multiple storefronts, we collected products from the 23 Amazon dedicated storefronts that were in use at this time.

Using this method, we collected a list of 114,542,719 Amazon URLs. Since not every Amazon URL is a URL to a product, we processed this URL list by searching each URL with the following regular expression:

This regular expression was designed to search for and detect a variety of ways that Amazon inserts Amazon Standard Identification Numbers (ASINs), Amazon’s unique product identifiers, into URLs and extract them from the URL. The result of this processing was a list of 19,074,613 unique ASINs.

To gather information on the availability of products in our five tested countries, we sequentially test ASINs in each region using an automated program to perform the following steps. First, we load amazon.com. Then we switch our location to the region that we are testing using Amazon’s location selector (see Figure 1). For each ASIN, we navigate to https://www.amazon.com/dp/[ASIN]/ to display that product’s detail page. We then parse that page for that product’s availability status. Note that at no point in our methodology do we sign into any Amazon account. If the product’s availability in a region is any of the following, we consider the product unavailable in that region:

- This item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location

- Currently unavailable

- Temporarily out of stock

While a product might be unavailable in a region due to legal or regulatory restrictions, there are also more benign reasons for a product being unavailable. Many such reasons are even alluded to in the above messages, such as sellers no longer shipping to that region or the product being out of stock among sellers shipping to that region.

As such, we are specifically interested in measuring which products cannot be shipped to a region even if there are shippers who have it in stock and are willing to ship it to that region. We call such products in that region restricted products since, even if they were in stock and there were shippers willing to ship them, Amazon would still restrict users from shipping them to that region.

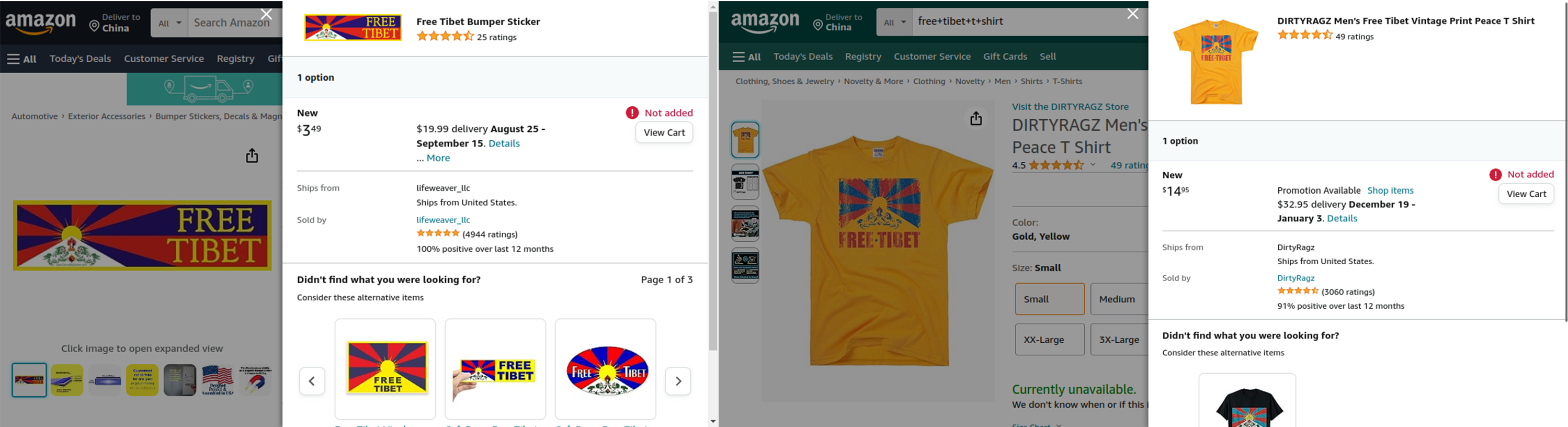

To discern which unavailable products are restricted, we exploit a special side channel to reveal if Amazon is preventing the unavailable product from being shipped to us. Namely, we perform the following additional steps via our automated program for any product found to be unavailable. First, we browse to https://www.amazon.com/dp/[ASIN]/?aod=1. Note that, compared to the previous URL we had browsed to, this one has appended to it the “?aod=1” query string. Enabling the “aod” parameter signals to Amazon that we want Amazon to render the all offers display (AOD). This advanced display lists all offers from shippers both willing to ship to the user’s specified region and who have the product in stock. Next to each shipper’s option is a button to add that offer to one’s cart (see Figure 2). We automate our program to click all of the “Add to cart” buttons on the AOD. We measure the number of buttons whose clicks resulted in the “Added” versus “Not added” messages. If there is at least one offer and all attempts to add offers to our cart result in a “Not added” error, we consider the product potentially restricted to our configured location. We schedule another test to run a week after the original, and, if that test has the same result (i.e., that there is at least one offer and all attempts to add offers to our cart result in a “Not added” error), then we consider that product restricted to the tested region. If there are no offers (i.e., there are no buttons to click), then we are unable to discern between the product being restricted in the tested region versus being unavailable for benign reasons such as being out of stock (see Table 1 for a summary of possible results). By exploiting how AOD status messages leak whether products are restricted, we are able to learn more about Amazon’s system of restricting product shipments to certain regions.

| Results from clicking “Add to cart” buttons | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| At least one “Added” | Product available |

| All and at least one “Not added” | Product restricted |

| There are no “Add to cart” buttons to click | Indeterminate |

Table 1: Summary of possible results from clicking “Add to cart” buttons and their interpretations.

Since many products on amazon.com do not ship internationally, we perform the following optimization to improve testing throughput. When testing unavailable products in each of the four countries for whether they are restricted, we skip testing products that are unavailable in Canada. We chose Canada as our control because of its geographical and legal similarity to the United States. This optimization reduced the number of unavailable products that we needed to test by over 85%. We were motivated to reduce the number of unavailable products that we needed to test because this process of the testing was the most time consuming.

Phase 2: Measuring censorship globally

In our Phase 1 methodology, we outlined the steps for how we determine which products are restricted to the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Yemen. However, Amazon supports delivering to 239 countries and other regions across the globe. In Phase 2, we now expand our measurement targeting the Middle East to a global measurement by limiting the number of products that we test in each region. We do so by feeding our results from Phase 1 into Phase 2.

Specifically, we are interested in the set of products that are restricted in at least one of the four Middle Eastern countries we analyzed. From this set, we created our Phase 2 test list by choosing 1,000 of these products uniformly at random with replacement. For each product in our Phase 2 test list, we perform a similar test as we did in Phase 1, except instead of only testing in four Middle Eastern countries we test whether that product is unavailable in and restricted in all 239 regions to which Amazon supports shipping. By doing this, we hope to have a broader understanding of how Amazon censorship is applied across the globe, at least as it relates to any product censorship that we had previously measured in the Middle East.

Experimental setup

We coded an implementation of our methodology in Python using the Selenium Web browser automation framework and executed the code on an Ubuntu Linux machine. We tested each search platform from a University of Toronto network. Phase 1 was performed from April 2023 to December 2023. Phase 2 was performed from May 2024 to June 2024.

Phase 1 Results

In this section we detail results from Phase 1 of our experiment.

Products tested

During our testing period, we were able to test product links collected in the Common Crawl dataset from the February/March 2023 archive working backwards until and partially including the September 2019 archive. Overall we tested 5,870,695 product links during this phase of the experiment. Among these, 2,005,852 (34%) were not (or were no longer) valid product pages, resulting in Amazon “Page Not Found” errors. Recall that many of the ASINs that we acquired were from dedicated storefronts other than the United States. Therefore, although many of these links may be to products no longer sold, most of these “Page not found” products are likely products that were never available on the US amazon.com storefront, only on the storefronts of other countries. In addition to the aforementioned “Page not found errors”, an additional 19,968 product links generated Amazon “Sorry! Something went wrong!” errors. Therefore, among the 5,870,695 product links tested, we tested 3,844,875 actual products.

Internal consistency of methodology

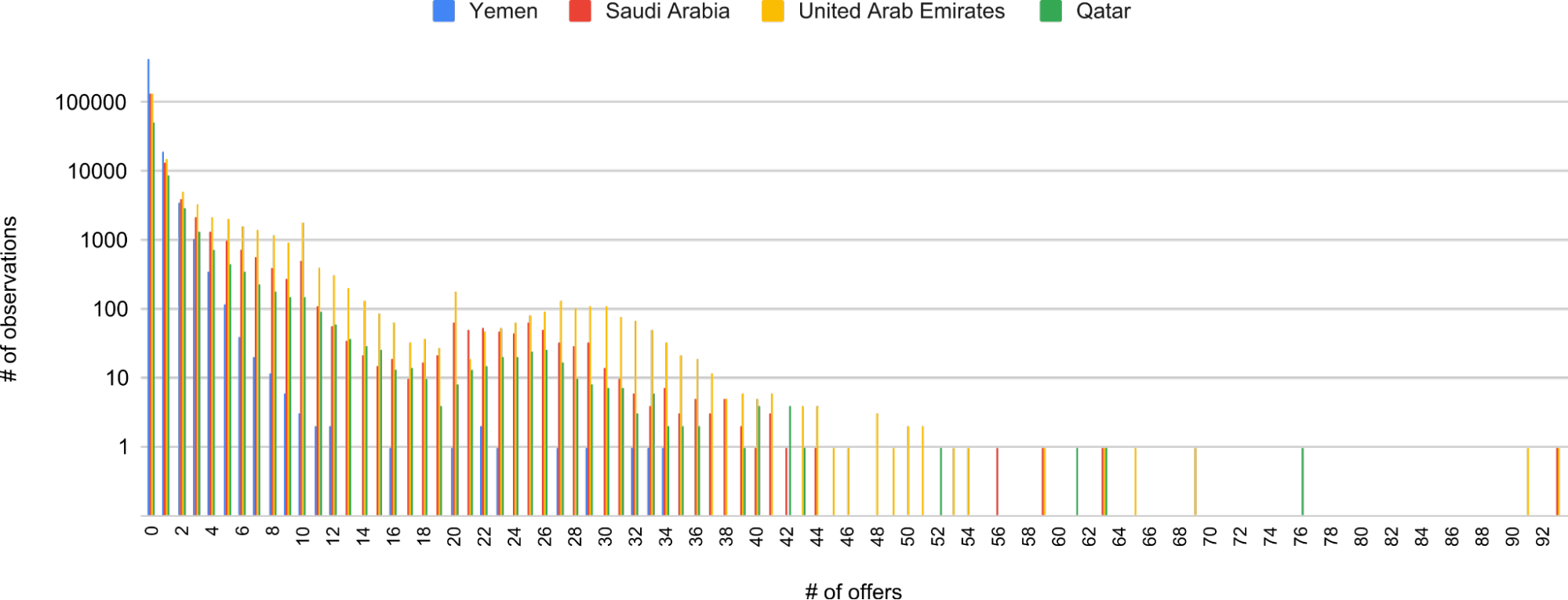

Across our regions tested, many products only had one offer (i.e., one seller offering to ship the product), yet others had as many as 93 offers (see Figure 3 and Table 2). In our methodology, we only consider a product restricted if all of its offers result in a “Not added” status. However, as some products only have one offer, we wanted to measure the consistency of results concerning products with multiple offers to gauge the reliability of results concerning products with a single offer. Specifically, we wished to approximate how reliable testing products with a single offer is by measuring how internally consistent testing products with multiple offers is. We do so by looking at the number of products whose offers had statuses which disagreed, namely, where at least one resulted in an “Added” status and at least one resulted in a “Not added” status.

| # of unavailable products with… | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| zero offers | one offer | > one offer | |

| Yemen | 429,571 | 19,074 | 5,198 |

| Saudi Arabia | 134,737 | 13,316 | 11,901 |

| UAE | 133,641 | 14,804 | 21,943 |

| Qatar | 51,455 | 8,876 | 6,997 |

| TOTAL | 749,404 | 56,070 | 46,039 |

Table 2: Summary of the numbers of offers per region.

Among our four countries of interest, we observed only 11 conflicting results: three in the UAE, one in Saudi Arabia, and seven in Yemen. We did not observe any noticeable trend in the type of products with conflicting results except that none had any clear motivation for being restricted (see Table 3 for a listing).

| Product | Region | # added | # not added |

|---|---|---|---|

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/1944565523/ | UAE | 8 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00GEBMPC0/ | UAE | 1 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/0521684188/ | UAE | 4 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/1933662859/ | Saudi Arabia | 33 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/0553152386/ | Yemen | 1 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/B004FTILGC/ | Yemen | 2 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00SK73UQQ/ | Yemen | 1 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/1784967335/ | Yemen | 1 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/140819208X/ | Yemen | 2 | 1 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0052CAZ2O/ | Yemen | 1 | 2 |

| https://www.amazon.com/dp/1905739001/ | Yemen | 2 | 2 |

Table 3: Products with conflicting results among offers.

Ten out of the 11 products had at least as many “Added” results as “Not added” results. Together with there being no clear rationale for their restriction, the “Not added” results are likely false positives. Since we only consider a product restricted if all of its offers result in “Not added” messages, we correctly interpret these cases of mixed results as being negative cases of restriction. There may be false positives which we were unable to detect, especially for products with only one offer available. However, given the low frequency of these false positives, namely, that among the 46,039 products tested with at least two offers, only 11 showed possible false positives, we can suspect an equally low rate among the products with only one offer. Specifically, if we assume the same false positive rate as what we had measured, then, among the 56,070 products with only one offer, we would expect only between 13 and 14 false positives.

Exclusion criteria

After beginning our Phase 1 experiment we noticed that many of the products that could not be added to our cart in the all offers display also presented an additional diagnostic message to the left of the “add to cart” button, stating (see Figure 4 for an example):

“This item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location. Please choose a different delivery location.”

Ultimately, varying by region, we found that between 16% and 47% of each region’s restricted products had at least one offer with this additional diagnostic message.

By looking at the nature of the products with these messages, the reason for these items’ inability to be shipped seemed unrelated to any type of religious or political censorship that Amazon might be applying. As such, in Phase 1, we exclude from analysis any offer in the all offers display that had this message, but, if some of the other offers for a product do not include this message, then we do not exclude those offers.

Censorship comparison

We saw the largest number of restricted products in the UAE, followed by Saudi Arabia, then Qatar. We observed the lowest number of restricted products in Yemen (see Table 4 for details).

| Region | # of known restricted products |

|---|---|

| UAE | 13,604 |

| Saudi Arabia | 9,590 |

| Qatar | 6,086 |

| Yemen | 1,817 |

| TOTAL (unique) | 17,050 |

Table 4: The number of known restricted products in each Phase 1 region studied.

We note, though, that this method of comparing the absolute number of known restricted products may be biased. Specifically, if some regions have more products generally available, such regions may appear to be more restricted due to having more restricted products as well. Therefore, a region with a larger number of known restricted products may not necessarily have a higher rate of restriction.

To more fairly compare Amazon’s restriction of products across these regions, we chose to generate Venn diagrams. In generating these diagrams, we only consider products for which there was at least one offer available in every region. In other words, we only consider products for which we have a clear yes or no result concerning whether it was restricted in every region featured in the diagram. We do this because we do not want our results concerning the number of restricted products to be biased toward regions in which we have more known results. Since each diagram features different regions, the totals therefore may not be consistent across diagrams due to this method of comparison.

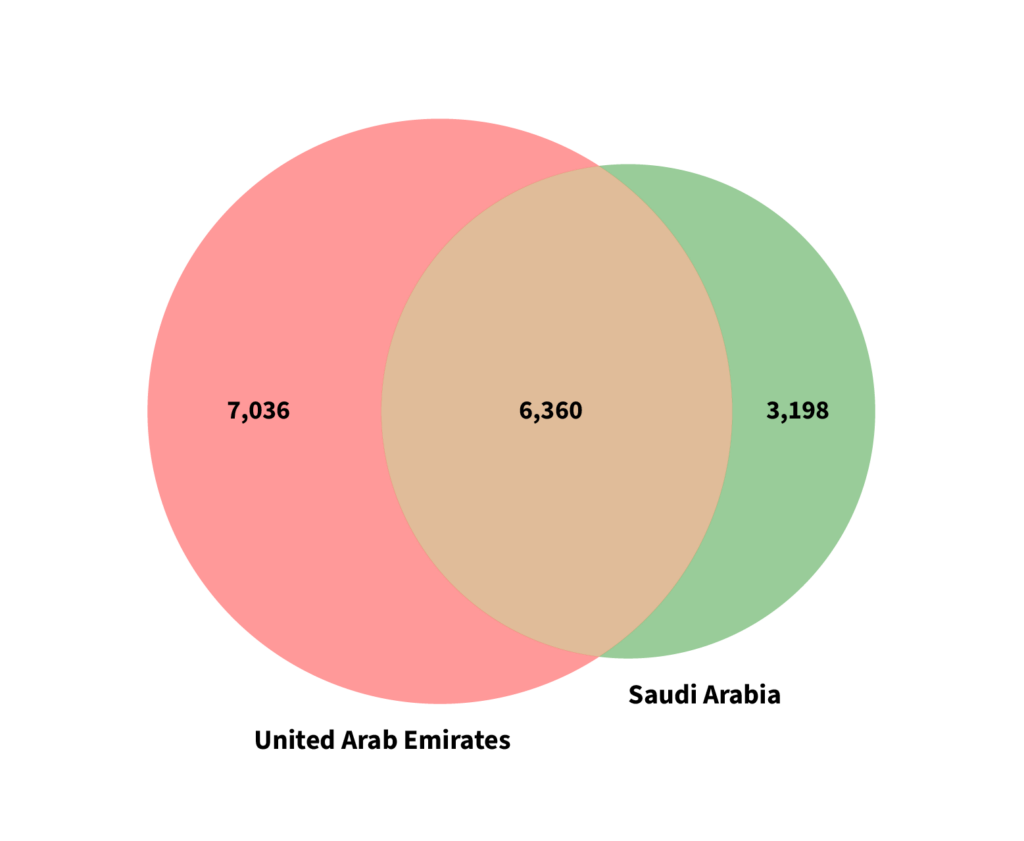

Between the UAE and Saudi Arabia, we found that the UAE restricted the largest number of products with around half of the products restricted in UAE also being restricted in Saudi Arabia (see Figure 5). We found that 6,360 products were restricted in common by the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

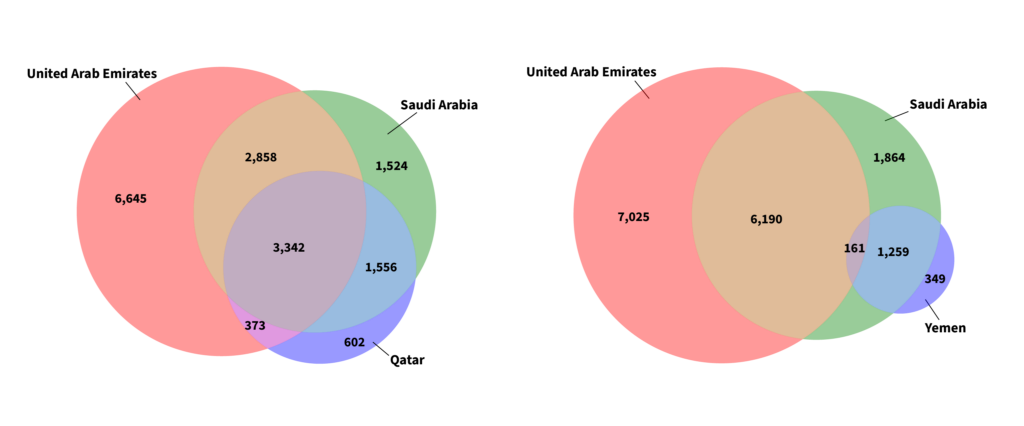

Comparing Qatar to the UAE and Saudi Arabia, we found that fewer products were restricted in Qatar and that almost all products restricted in Qatar were also restricted in Saudi Arabia and that most of the products restricted in Qatar were also restricted in the UAE (see Figure 6). Comparing Yemen to the UAE and Saudi Arabia, we found that fewer products were restricted in Yemen and that almost all products restricted in Yemen were restricted in Saudi Arabia (see Figure 6).

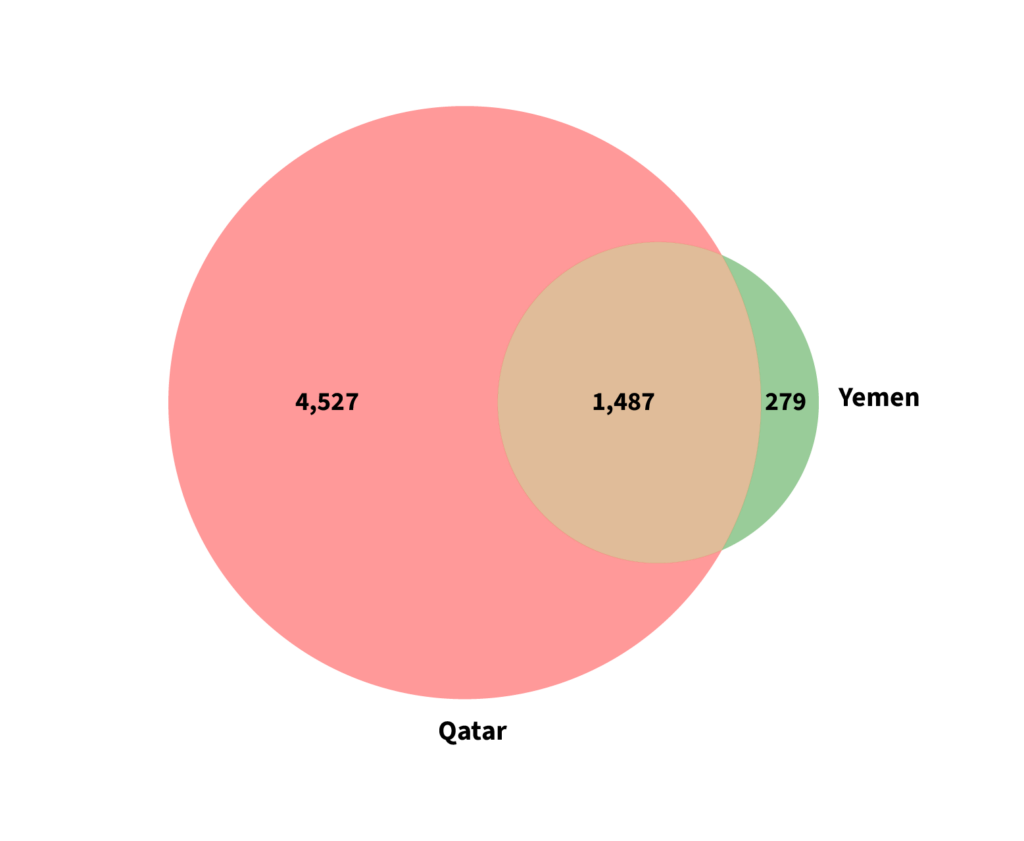

Finally, comparing Qatar to Yemen, we found that Yemen had the fewest number of restricted products and that almost all products restricted in Yemen were also restricted in Qatar (see Figure 7).

Notably, we found different levels of restriction among these four regions despite their cultural and geographic proximity in the Middle East. Namely, the UAE featured the highest level of restricted products, followed by Saudi Arabia, then Qatar, with Yemen having the fewest. Since we found that the UAE and Saudi Arabia feature the most products and because almost all products restricted in Qatar and Yemen were also restricted in either the UAE or Saudi Arabia, we focus the remainder of our analysis on the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Analysis of availability messaging

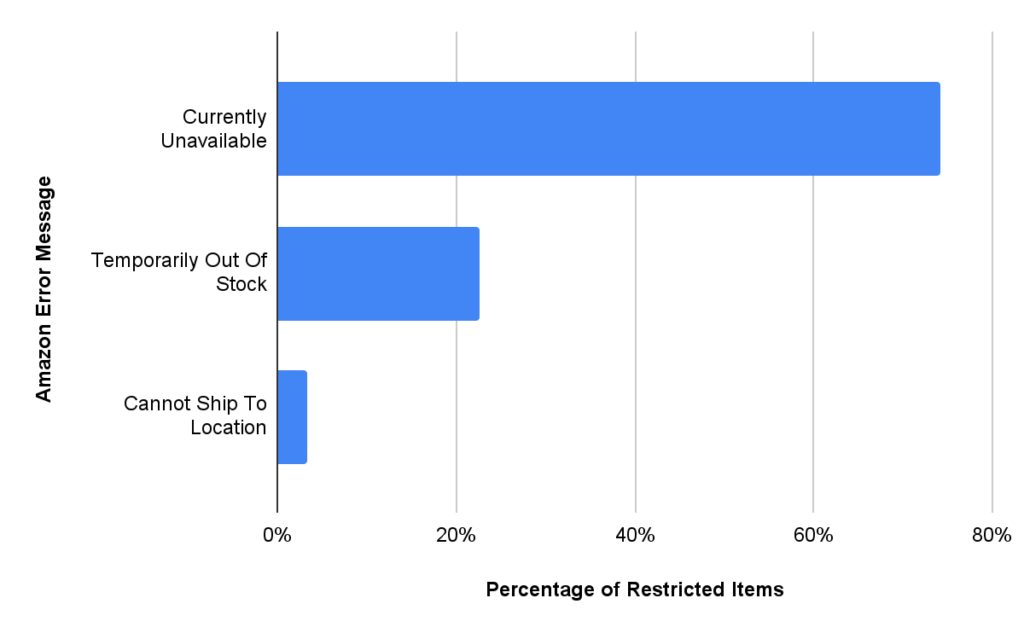

In our dataset, products that are restricted by Amazon presented different and inconsistent messages to the user. The messaging around the rationale for why a certain product is restricted could inform the user as to the reason why items are unavailable. However, among all of the restricted products identified by this study, none presented a message to the user explaining that the items were unavailable due to regulatory reasons. Instead, each item was communicated as either being “currently unavailable”, “temporarily out of stock”, or that “this item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location”. The messaging presented to users for these restricted items is vague and unclear.

The message presented to users was also inconsistent (see Figure 8). In reviewing each restricted item we could not determine why attempting to ship some restricted items resulted in one message versus another. Instead, Amazon used more generic and sometimes misleading terminology when communicating that restricted items cannot be shipped.

Analysis of censorship in Saudi Arabia and the UAE by Amazon product category

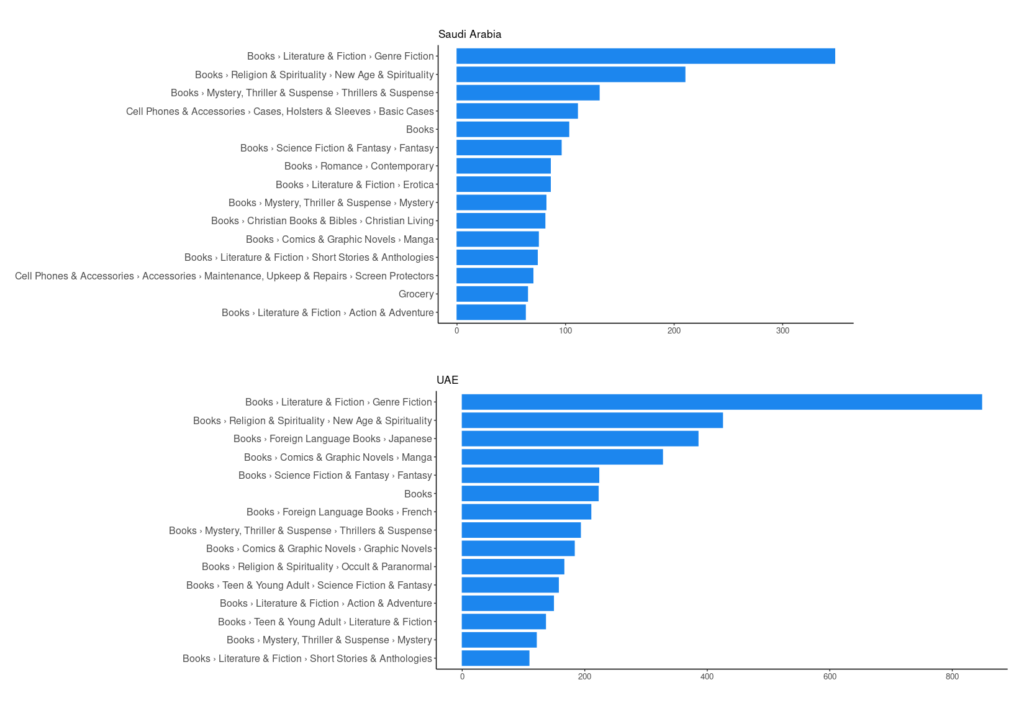

Figure 9 shows the overall products by categories that are restricted in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This is based on Amazon’s own categorization of a product, which can include both specific categories (e.g., “Book -> Science Fiction”) as well as more general categories (e.g., “Book -> Genre Fiction”). The restricted products are dominated largely by book-related categories, mainly “Genre Fiction” and “New Age & Spirituality”, which are the top one and two restricted categories respectively in both countries. Japanese Manga and Fantasy book categories are also present in the top 15 restricted products by categories in both countries. The book-related categories that are most restricted in Saudi Arabia include “Thrillers & Suspense”, “Erotica”, “Christian Living”, “Anthologies”, and “Action & Adventure”. Non-book-related product categories restricted in Saudi Arabia include “Cell Phone Cases”, “Screen Protectors”, and “Groceries”. In the UAE the book categories most restricted include “Thrillers and Suspense”, “French”, “Occult & Paranormal”, “Mystery”, and “Short Stories”. There are no non-book categories represented in the top 15 restricted products in the UAE.

Although our Phase 1 experiment began in April 2023, ending in December 2023, it was only on June 6, 2023, that we began capturing the Amazon category for products that we did not find restricted in any region. Considering only the books that we tested since that time, we find that Amazon censored 8,965 out of the 796,081 books in that sample in at least one of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, or Yemen. Therefore, we estimate that Amazon applies censorship to over 1.1% of the books sold on amazon.com. Since our method cannot find all instances of censorship, this estimate is only a lower bound, and the real proportion may be much larger.

Analysis of censorship in Saudi Arabia and the UAE by censor motivation

In the previous section, our analysis was limited to understanding the motivation behind Amazon’s shipping restrictions by looking at the categories Amazon assigns each restricted product. While this kind of analysis tells us which products are restricted, it does a poor job of describing the motivations for why it is restricted. To address this gap, we conduct a qualitative analysis, employing a more nuanced approach to decipher the underlying reasons for these restrictions.

We selected a random sample of 200 products, 100 items restricted from shipment to the UAE and another 100 items restricted from shipment to Saudi Arabia, to understand the breadth of Amazon’s shipping restrictions across various product categories. This random selection sought to minimize the bias and ensure representativeness.

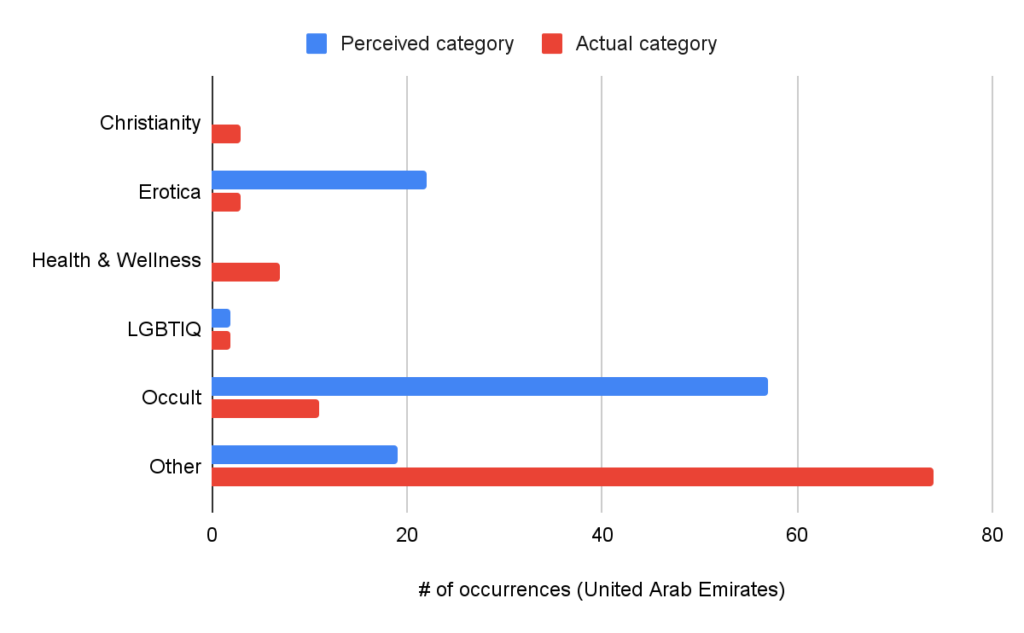

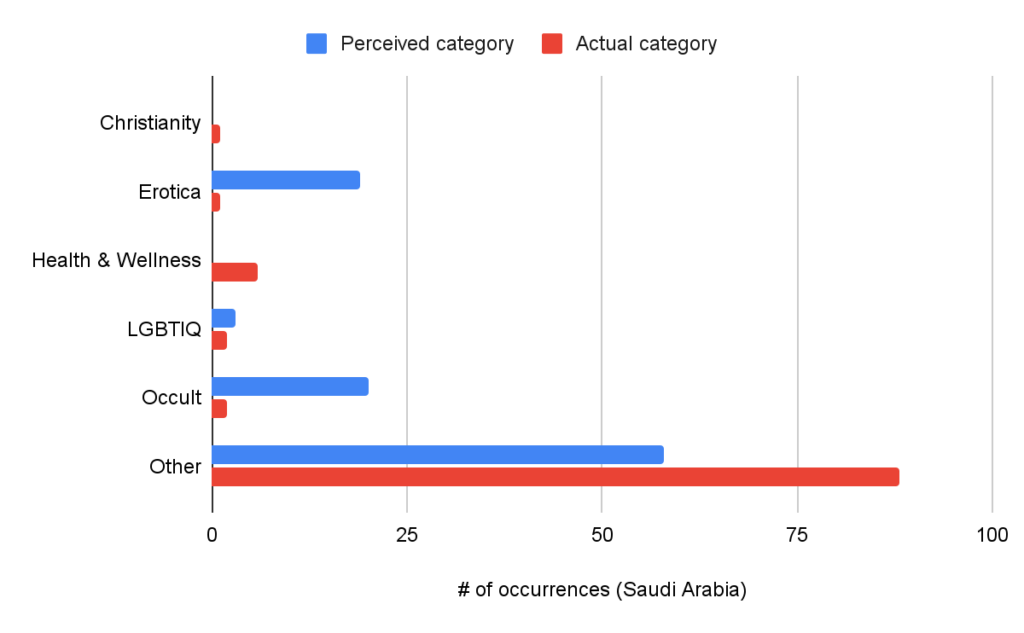

We analyzed items from this random sample based on their titles and descriptions. In some cases when the product information was not listed in the description, we conducted further background research to understand the product. We categorized them based on the actual nature of the products and the perceived category of the products. The latter refers to a category we inferred based on potentially sensitive keywords within the products’ description or title that may be triggering Amazon’s algorithms to perceive it as being under a category. As one example, Nietzsche’s Gay Science contains the word “gay” in the title, suggesting that it was censored for containing the word “gay”, even though the book is a philosophical work that does not speak to LGBTIQ topics. This dual categorization was designed to uncover discrepancies between a product’s apparent content and its perception by Amazon’s algorithms (see Figures 10 and 11).

Both categorizations consisted of the following categories: “LGBTIQ”, “Occult”, “Erotica”, “Overbroad”, “Christianity”, “Health & Wellness”, and “Other”. The actual category of a product that we assign is based on our analysis of the items’ titles and descriptions, whereas the perceived category is also based on the identification of certain keywords believed to trigger Amazon’s censorship algorithm and influence the miscategorization of some items.

Our review of items restricted in the UAE and Saudi Arabia highlights Amazon’s possible miscategorization of items. This is especially concerning as miscategorization ultimately has the effect of imposing unnecessary censorship rules onto users. Any case of miscategorization highlights a possibility that these decisions are being made automatically rather than with the proper care and diligence. In the following sections we highlight select items among each of our categories, including suspected cases of over-blocking.

LGBTIQ

Examples of LGBTIQ content from our random sample of restricted products include a movie featuring gay characters—and containing the word “gay” in its title—and a book on the history of the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany.

Other types of LGBTIQ content from outside of this sample that we observed include workbooks relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, trans and genderqueer erotica, books on LGBTIQ criminalization in the US and queer activism, and cookbooks based on queer community-led culinary practices.

However, many products containing the word “rainbow” in their descriptions were censored despite not being otherwise related to LGBTIQ themes. Such products included rainbow-colored hair extensions, a travel case, a video game, a movie DVD, a detective novel called Mister Rainbow, and Mentos rainbow candy. These findings reveal that Amazon’s LGBTIQ censorship is overly broad, capturing products such as candy that are not illegal in any country.

As we noted previously, many books were also collaterally censored for containing the word “gay” in their title or description. As a chief example, Nietzsche’s Gay Science was censored, despite being a philosophical work unrelated to LGBTIQ topics.

Occult

In our random sample, we found books related to the occult and the paranormal including those on tarot, fairy tales, demons, jinn, witchcraft, astrology, crystals, freemasonry, astral projection, and Bigfoot. Much of the children’s books’ censorship seemed motivated by censoring the occult, although it is unclear whether these children’s books were expressly targeted or collateral damage of some larger censorship strategy. For example, in our random sample are children’s books related to jinn, witches, wizards, and necromancy. Our random sample also featured one book describing how to write fictional books relating to monsters as well as a book about Harry Potter.

Although not represented in our smaller random sample, in our larger data set we observed books relating to Thelema, an occultist movement, as well as its founder, Aleister Crowley. Many books related to extraterrestrial aliens and ufology at large were also restricted. We also observed a Dell Alienware laptop that was restricted, although we are unsure if this is due to the product’s allusion to aliens or due to electronics or communications regulations. Notably, while we observed multiple restricted products relating to oracles and divination both inside and outside of our random sample, we also found a large number of books outside of our sample related to the Oracle database software that seem to have also been caught up by the filter, suggesting that books related to oracles are over-censored.

The banning of books, even children’s books, related to the occult or magic is often religiously motivated under the belief that they are demonic or evil. For instance, Catholic schools in Canada and the United States have banned Harry Potter books. Even aliens and UFOs, while seemingly nonreligious, have been suggested by many to be related to demonic visitation, and the idea of extraplanetary visitors challenges a common religious notion of humankind being the center of creation.

Similarly, in the Middle East context, it may not be surprising to find that children’s books discussing magic and witchcraft are also censored in both Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This stance aligns with both countries’ long histories of prosecuting individuals accused of practicing witchcraft and sorcery. For instance, in Saudi Arabia, the Harry Potter books were specifically banned for containing themes perceived as occult, Satanic, depicting violence, and allegedly undermining family values.

Erotica

We identified a significant number of restricted books in our random sample whose censorship was likely motivated by restricting erotica, even though they did not contain erotica, including literature, humor, photography, travel, self-help, classic literature, among others. A notable example is Never Mind the Botox, a book that features the lives of four women working in cosmetic surgery and their daily struggles. Whereas cosmetic surgery is legal in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, we think that certain keywords in the book description have resulted in its miscategorization under “erotica”.

Another example is Sex Addiction Survival Guide: A Practical Workbook for Reconnecting to Yourself and Others, which is a guideline targeting individuals who are struggling with sex and pornography addiction issues, motivating them to move toward a healthier connection to self and others. Censored, it was most likely flagged as an “erotic” book based on certain words in the title and description, such as (sex, porn, sexual, hypersexuality, etc.).

Finally, Klarissa Dreams Redux: An Illuminated Anthology is a collection of poetry and other writings in the context of Klarissa Kocsis’s paintings. In the description of the book, however, the author is described as a “breast cancer survivor” and as having “earned a reputation for portraiture and nudes”, either of which may be triggering Amazon censorship. Literature relating to breast cancer is common collateral damage for overblocking censorship filters on various platforms.

Like the occult, religious motivations are often behind the banning of erotic books. Schools’ libraries in the US banned books on sex and sexuality, among other topics. Similarly, in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, the long history of bans on erotic content and certain topics considered “taboo” has led to widespread self-censorship among publishers and translators. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s Law of Printed Materials and Publication states in Article 9 that publications are allowed when they “do not violate the provisions of Islamic Sharia”. Although the language of this law is vague, the Executive Regulations of the Publications and Publishing System was more explicit in specifying the prohibited topics, including the “spread of obscenity”.

Christianity

We identified numerous censored books related to Christianity in our random sample. However, since works related to Christianity often deal with topics such as demons or the devil, we believe that these books were collateral censorship, and that Amazon’s censorship filter perceives them as being related to other topics.

For example, many censored books relating to Christianity mention demons or the devil, such as The Soul of The Apostolate. The book emphasizes the success of Christian apostolic work, highlighting that it hinges not merely on activity but fundamentally on a robust interior life. However, it also advertises to reveal the “Devil’s special temptations for those working for Our Lord”. Another example is the censorship of Get Thee Behind Me, Satan: Rejecting Evil which raises questions about biblical facts and their relation to devils, but the work is ultimately concerned with motivating the need for vigilance against the pervasive appeal of evil.

There was also one Christian book likely censored due to erotic themes. Moral Ambiguity is the fictional story of Kevin Gregory, a celebrated singer, exposing the corrupt practices and moral hypocrisy of a powerful televangelist. While the book is primarily concerned with the main protagonist revealing the hypocrisy of religious authority, the book’s description also alludes to the antagonist’s motivations of greed and sex.

Despite many Christianity-related books being restricted from shipment to the UAE, the UAE has been promoting their openness to other religions. The UAE has created the Ministry of Tolerance and Coexistence that aims to “encourage interfaith dialogue” as part of its mission. Notably, the US Department of State’s 2022 Report on International Religious Freedom concerning the UAE underscored that there are available books in the UAE on a variety of topics, including non-Islamic religions and pro-atheism. Therefore, it is unclear why Amazon’s censorship restricts shipment of so many Christian books to the UAE.

Health and wellness

Restricted products include condoms of several brands, sex toys such as vibrators, and sex education, sexual health, and gender identity books and textbooks. Lubricants are also restricted, although automotive greases with the word “lubricant” in their descriptions were also among the restricted products in our random sample.

Preventing access to sexual education materials, contraceptive methods, and other sex-related products can impact the physical and emotional wellbeing of a population, as well as the safety of its most vulnerable members. Studies on Russian sex education campaigns—or the lack thereof—show that hindering one’s contact with sexual health information leads to an increased transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), a rise in sexual assault and harassment, and, among other consequences, the use of abortions as a main method of contraception. Conservatism and the insistence on protecting children’s “innocence” have proven to be the main factors driving the opposition to the implementation of sex education curricula in schools and the censorship of sexual health content in media.

In such places as the MENA region, there is a lack of preventive programs and youth-friendly services. A 2004 study of Lebanese people aged 15–24 shows that condom use was low, at only 37% among those having regular casual sex. Although population-based data remain lacking, the MENA region has been experiencing a rise in STI prevalence among its population. This is a consequence of the lack of preventive programs such as vaccination and school-based sex education.

Other

A large number of products in the “Other” category include those which are heavily regulated, such as products related to WiFi or car seats. This is especially the case in Saudi Arabia, where we also saw a large number of restricted products related to mobile phones. However, the large discrepancy between the number of products in the “Other” perceived category and the “Other” actual category points to the large amount of overly broad filtering which perceives certain products as being related to restricted categories but in actuality they are unrelated.

For a variety of products that we measured we could not identify any reason for their restriction. As one example, we found that Malala Yousafzai’s She Persisted was censored in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. While we might speculate that such a book could be politically sensitive in those countries, it does not fit into any of the above categories of products. Moreover, other Malala Yousafzai titles were available in these countries, so it is unclear if this is intended censorship or if it is collateral damage from some overly broad filtering rule. There may also exist other motivations for product restriction other than those which we could identify.

Other languages

Not all products within our 200 product random sample were in the English language. Thirteen restricted products from non-English language products were also included. These are products in Japanese (six products), French (five products), and German (two products). All restricted non-English media was for written material like books, including many comics, except for one German movie, Könige der Welt, a documentary about addiction and success in the music business. Many of the blocks within other languages can be categorized in themes identified previously such as the occult, erotica or sexual health information.

Many of the restricted Japanese products are Japanese comic books or “manga”. Many of these restricted products contain occult themes or contain violent content. Some restricted manga is marketed to a younger audience such as My Hero Academia and Dragon Quest, which we suspect is restricted due to an overbroad interpretation of the occult. Another suspected miscategorization is a book by Japanese author Mayumi Tanimoto called “キャリアポルノは人生の無駄だ” (Career Porn is a Waste of Life). This book is both a humorous and earnest criticism of the work environment and labor conditions in Japan. We suspect that the characterization of this issue in the context of “career porn” has led to an erroneous miscategorization of the product as being pornographic. This is possibly due to the inclusion of the characters “ポルノ” (porno) in either the title or description.

Restricted French language content includes sexual health information such as a book about the Kama Sutra, a guidebook for performing sexual acts, and a humorous guide to dating. We suspect that two French books were captured by censorship rules targeting the occult: a young adult fantasy novel about the fictitious black magic book the “Necronomicon”, and a book about Tarot card interpretation. The one restricted German book is a children’s fantasy book about a girl named Willow, who loves nature, according to the title. We suspect that this book was also captured by occult-targeting censorship.

Phase 2 results

In this section, we detail results from Phase 2 of our experiment in which we tested across all 239 Amazon regions 1,000 products restricted in at least one of four Middle Eastern countries.

Comparison of product availability across regions

To compare how product availability varied across all 239 regions, we clustered each region according to the inter-similarity of the products that are restricted in each region. Specifically, we compare each product’s results using their hamming distance h(a, b), where h(a, b) is 1 if a = b, 0 otherwise.

To compare two vectors of results, either across every region keeping the product fixed, or across every product keeping the region fixed, we use the distance metric

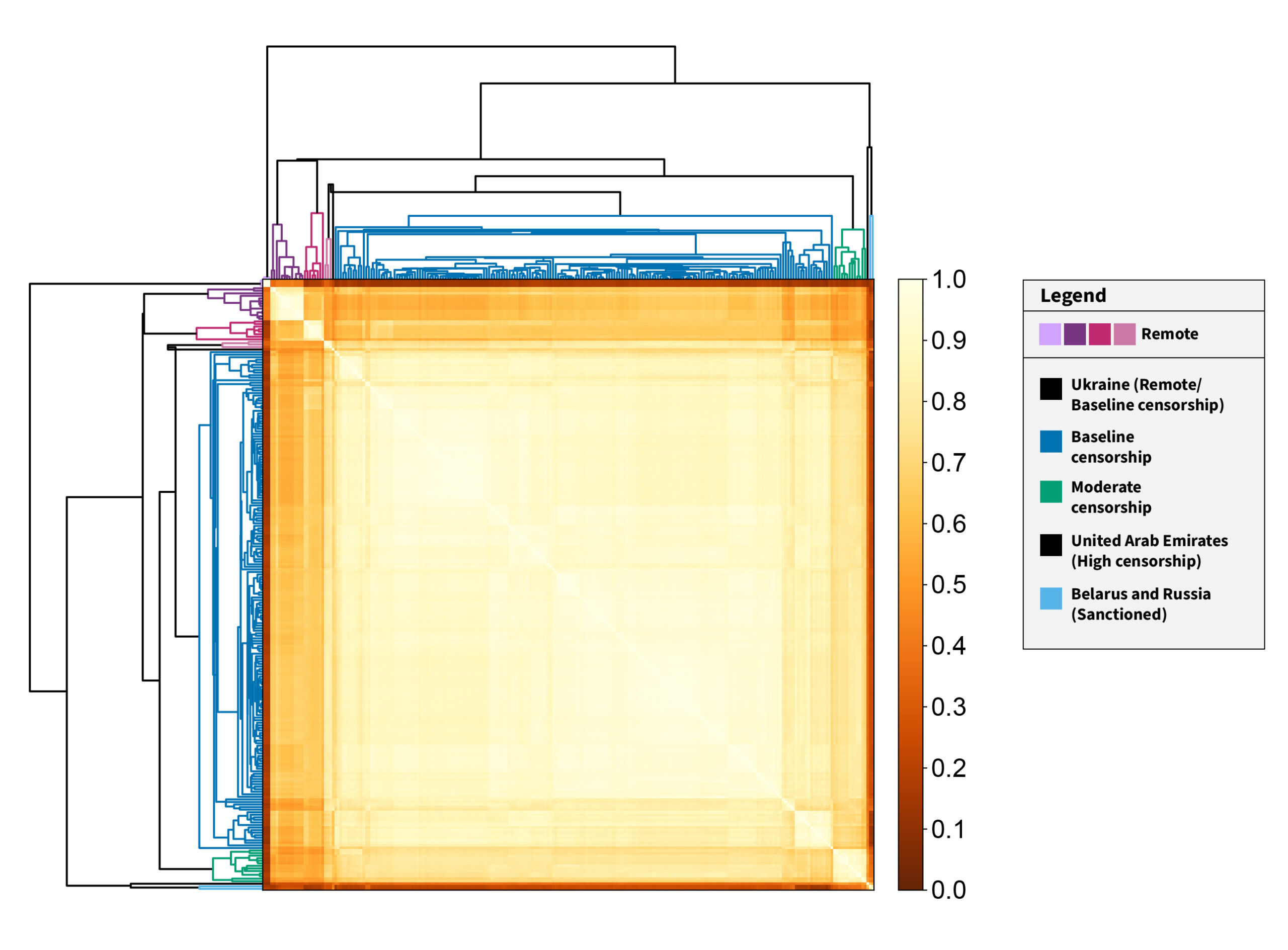

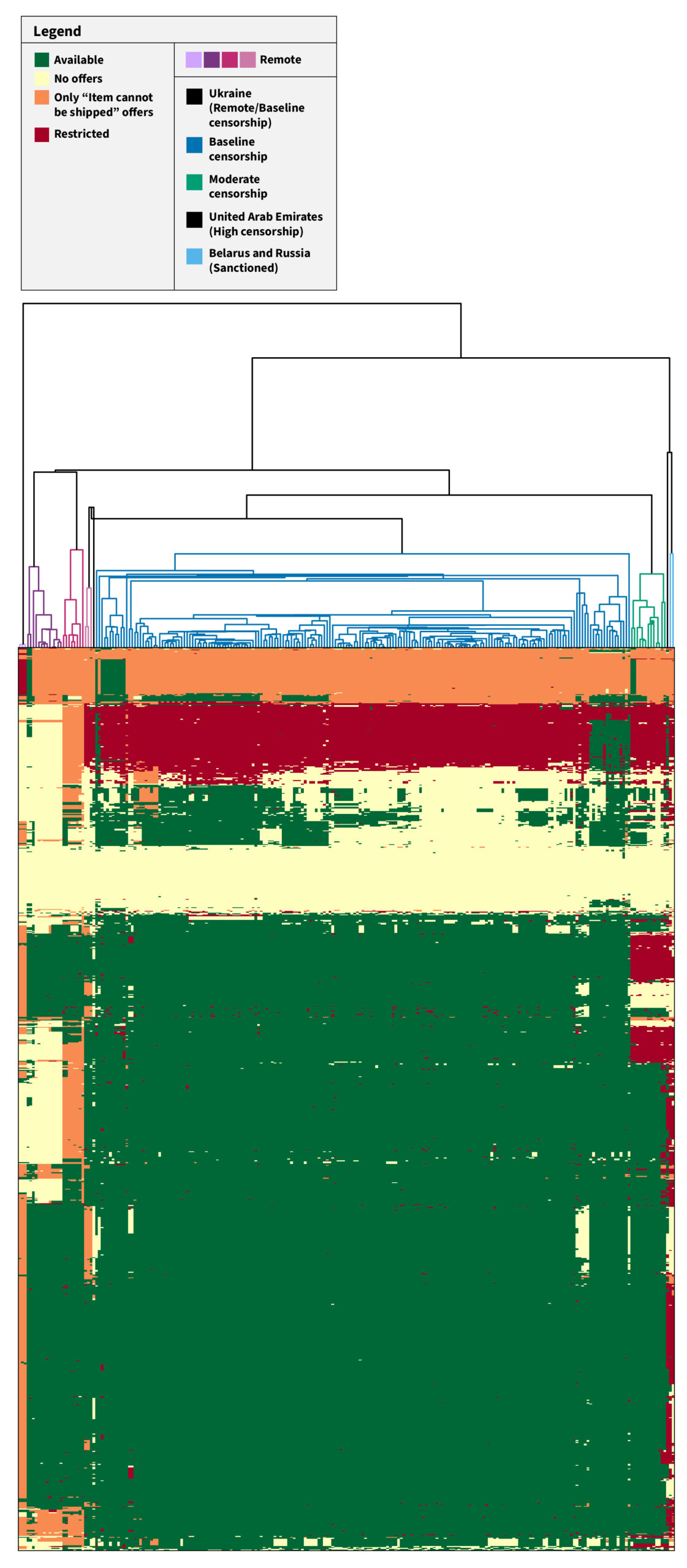

Using this metric, we hierarchically clustered each region. The resulting clustered similarity matrices and dendrograms are in Figures 12 and 13. In Figure 12 both axes are regions and each cell represents two regions’ restriction similarity, but in Figure 13 the Y-axis varies over products, and we hierarchically cluster the rows of different products in the same manner as we did the columns of different regions. Each cell in Figure 13 represents whether a product is censored in a region.

In Figure 13, we identified the four leftmost clusters as having limited shipping options due to varying degrees of physical or logistical remoteness. At the extreme, some of these locations are remote, unpopulated islands (e.g., Bouvet Island), which would pose obvious shipping challenges. Other locations are not physically remote but are logistically difficult to ship to due to ongoing political instability or military conflicts. As such we refer to these four as different “remote” clusters.

Moving rightward is a singleton cluster consisting of Ukraine followed by a large 195-member cluster with regions we consider to have baseline censorship. Inside of the baseline censorship, there is some variation such as which types of groceries or health supplements can be delivered or whether products from Amazon Global Store UK can be delivered. Generally, however, in this cluster, although some products were restricted, we did not find any that could be categorized as religious or political censorship. Ukraine being clustered in between the collection of four “remote” clusters and the baseline censorship cluster suggests that the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine may have limited courier’s access to the region, although not to the same extent as others.

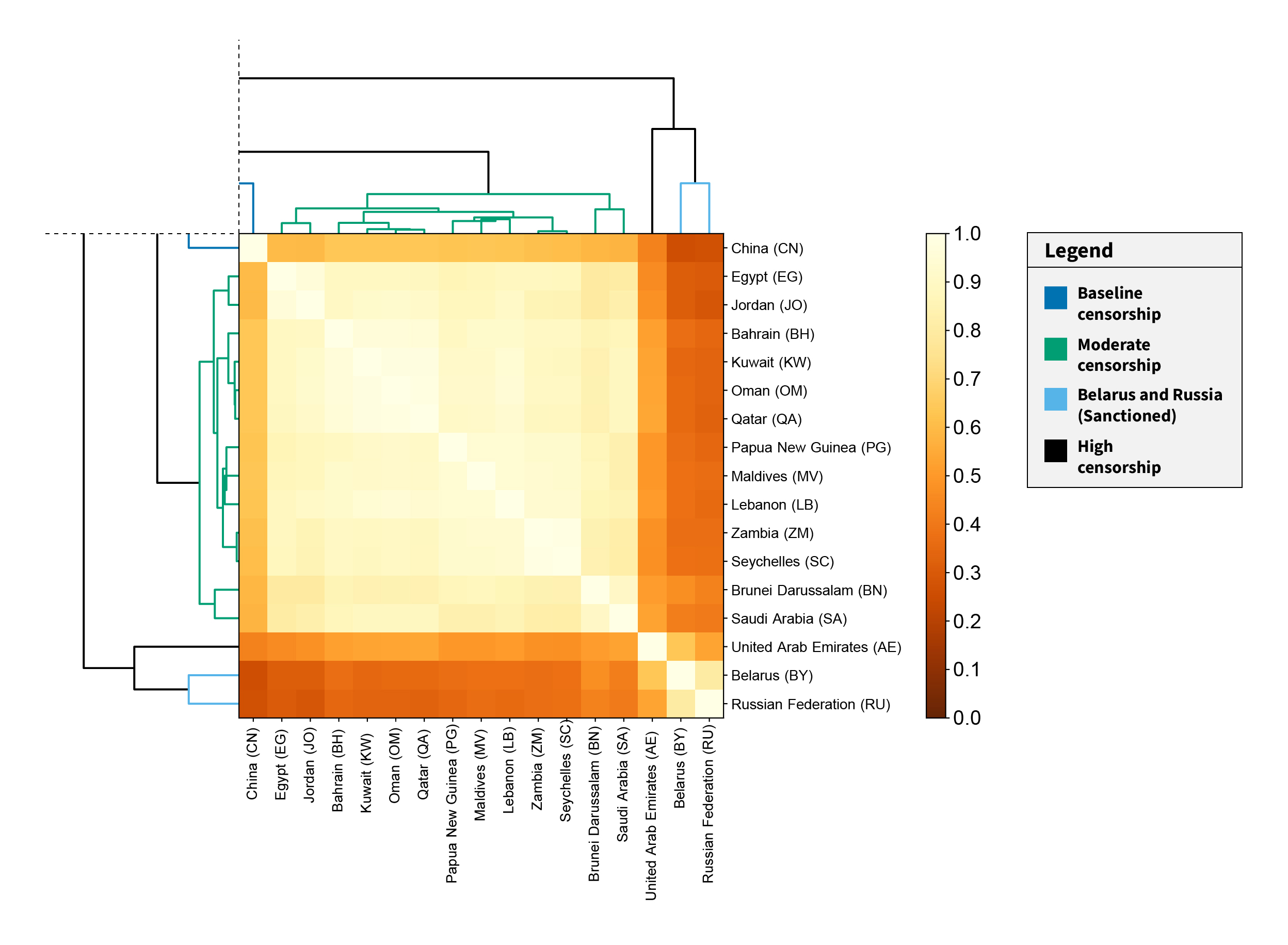

Zooming in on the 17 members in the lower right of Figure 12, we have Figure 14.

Beginning from the upper left, we first see China, the final member of the baseline censorship cluster. Despite Amazon censoring products in this region, we did not generally observe evidence of censorship to this region in our Phase 2 experiment for reasons which we explain in the “Chinese censorship” section below. However, we do note that while it was in the baseline censorship cluster, it was the region in this cluster that was clustered the closest to the more censored regions to its right.

Moving rightward, we see Jordan, Egypt, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, Lebanon, Papua New Guinea, Maldives, Zambia, and Seychelles forming a cluster. Brunei Darussalam and Saudi Arabia are also in this cluster. Due to this cluster’s censorship of LGBTIQ, occult, and other topics that do not match that of the UAE’s, we refer to this as the moderate censorship cluster. However, while the dendrogram tree is shallow between Brunei Darussalam and Saudi Arabia, suggesting their censorship is highly similar to each other’s, the dendrogram link between this pair of countries and the remainder of the “moderate censorship” cluster is taller, suggesting that this pair of countries has less in common with the remainder of the cluster than they do with each other. We found that various phone accessories were restricted in Brunei Darussalam and Saudi Arabia. We are unclear if this is the result of some regulation uniquely affecting these regions or if this is the product of some kind of censorship which we do not presently understand.

Continuing rightward, we have the UAE in a singleton cluster. In Phase 1 we identified it as being the most censored region among those analyzed, and our Phase 2 results are similar. As such we identify it as the high censorship cluster.

Finally, we see Belarus and the Russian Federation forming a cluster. Following the 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Amazon announced suspension of shipment to these countries. As such we refer to this as the sanctioned cluster.

These results show that our clustering technique was more capable of revealing clusters of regions with similar restrictions as well as for uncovering those restrictions themselves. These results also shed light on our previous Phase 1 findings which found that the UAE and Saudi Arabia censored the most, followed by Qatar, with Yemen censoring the least. We can now identify the UAE as belonging to the high censorship group, Saudi Arabia and Qatar as belonging to the moderate censorship group (with Saudi Arabia having additional restrictions affecting, e.g., phone accessories), and Yemen as belonging to the baseline censorship group.

Product categories that are most restricted

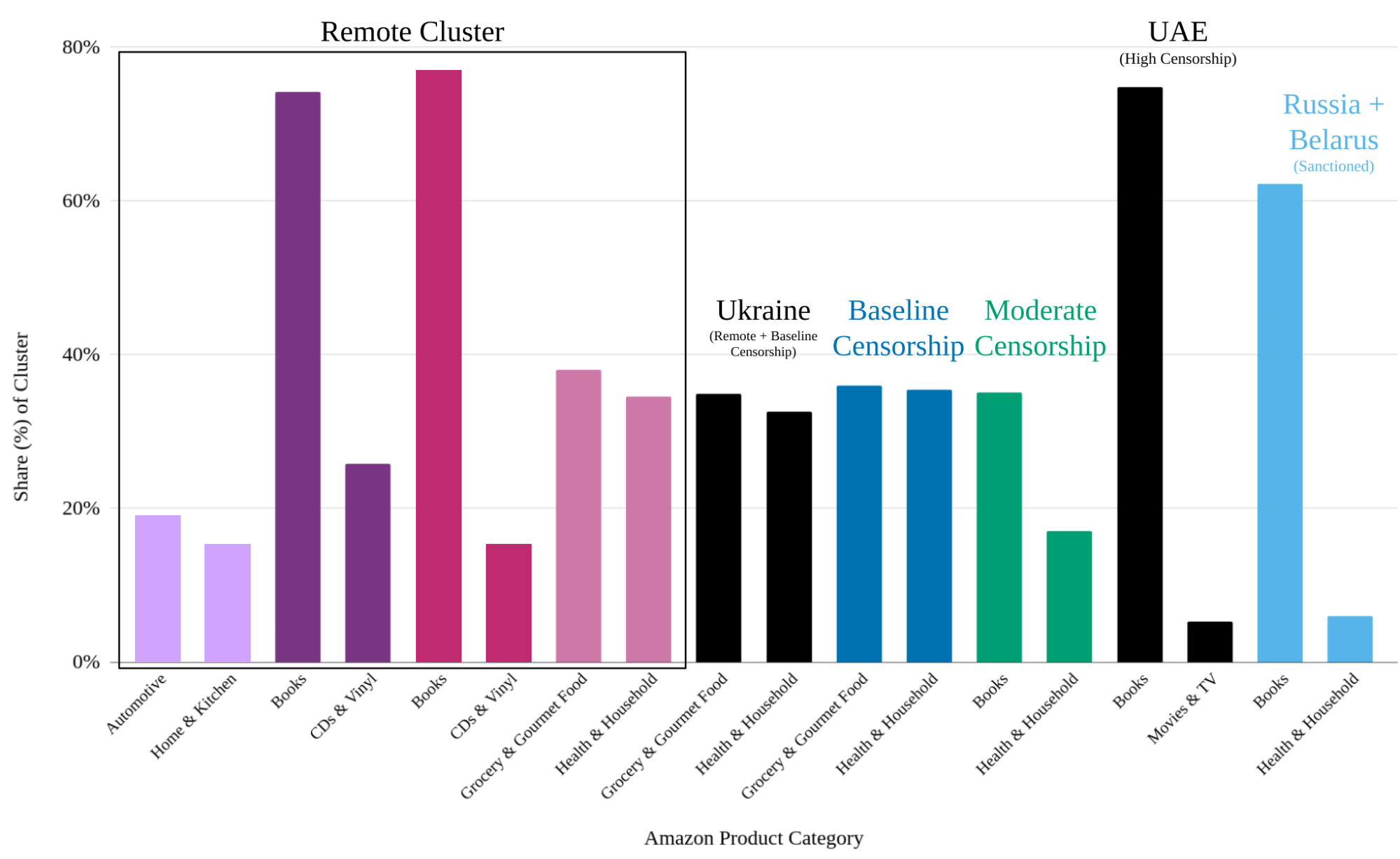

With the regions organized into clusters, we now review each cluster’s most restricted product categories. We find that for the moderate censorship, high censorship, and sanctioned clusters the largest restricted category is “Books” (see Figure 15). The UAE has the largest percentage difference (69.47%) between “Books” and the next largest category, “Movies & TV”. Among less censored region clusters the top category is most often (three out of six) “Grocery and Gourmet Food” followed by “Books” (two out of six) and “Automotive” (one out of six). We see that less censored region clusters are more likely to not ship products for regulatory reasons (food and automotive) while more censored clusters are more likely to not ship media (books or movies). There are two notable exceptions to this among remote regions where books and music CDs are the top one and two categories not shipped. Among these regions, this finding reflects that books are a high proportion of the sample set that we tested in Phase 2 as well as the predominant category of product sold on Amazon.

Censorship masterlists

While our analysis fleshed out various reasons for restrictions on shipping, including the remoteness of unpopulated islands or Amazon’s voluntary sanctions against Russia and Belarus, we note that when we restrict our concern to only politically and religiously motivated censorship, we observe three clusters: the baseline censorship cluster, the moderate censorship cluster, and the high censorship cluster.

We believe that these clusters are explained by the application of three different censorship masterlists which Amazon uses to simplify the process of censorship. By creating masterlists of censored products and assigning regions to each masterlist, Amazon can perform censorship more expeditiously versus applying censorship specifically tailored to each region. This “three sizes fits all” approach may help explain the over-broadness of much of the censorship that we observed.

Chinese censorship

In Phase 2 of our experiment, we observed few products censored when shipping to China. Given China’s stringent regulatory requirements concerning political speech, we investigated why we saw so few products censored in defiance of our expectations.

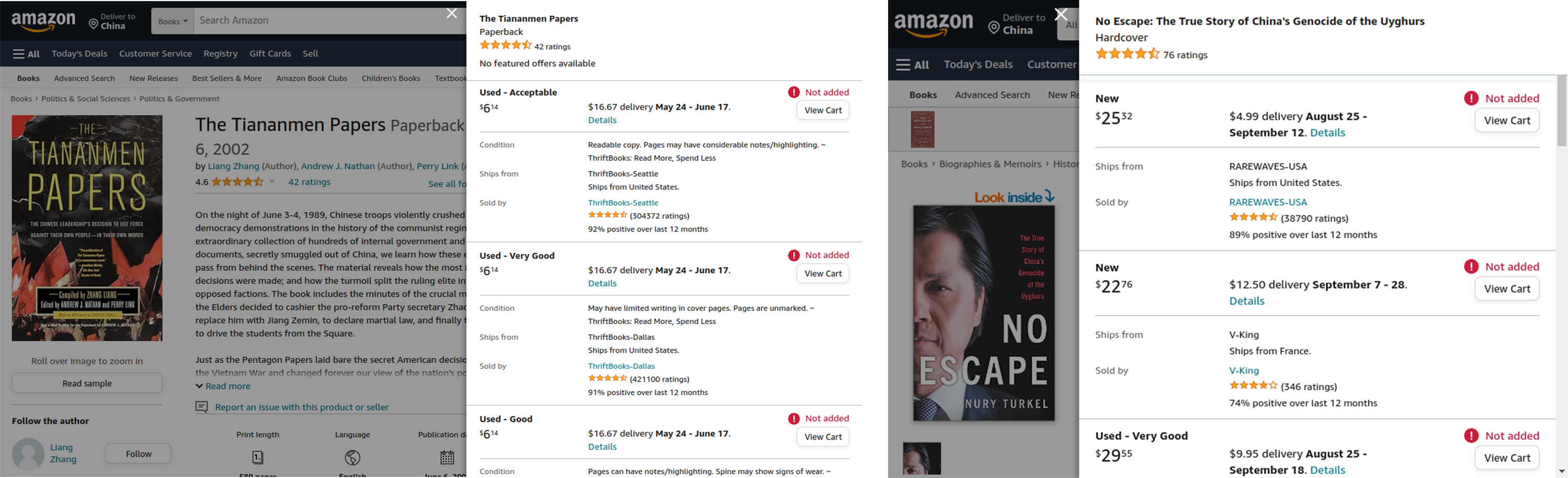

By manually testing items that we suspected might be censored, we found books (see Figure 16) and other products (see Figure 17) that are sensitive in China were censored when shipping to China. However, we did not observe these products censored in our Phase 2 experiment because that experiment only finds products censored in regions that were censored in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Since the UAE/Saudi Arabia and China have largely different censorship motivations, we would expect their censorship to have little overlap.

However, we believe that the methodology employed in this report would work for further exploring censorship in China if China had been studied during Phase 1. We leave such an investigation to future work.

Incompletely applied Russian sanctions

Despite Amazon’s announcement of suspension of shipments to Russia and Belarus, we found multiple products that could be shipped to these regions, including a mystery novel, a Nativity toy play set, and a tube of seafood-flavored cat toothpaste. We can identify no other commonality among these and other products which we could ship to Russia and Belarus. However, they point to the incomplete application of Amazon’s suspension of shipments to these regions.

Revisiting “item cannot be shipped” products

In Phase 1, we excluded from analysis all offers for products with an “item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location” message displayed in the all offers display. We did this to focus on products which were affected by religious or political censorship. In Phase 2, seeking a more holistic understanding of product availability on Amazon, we did not perform such exclusions, and thus we can now speak to the cause of these messages.

In Figure 13, orange cells in the matrix represent products that would have been excluded in Phase 1 due to having all of their offers showing the “item cannot be shipped” message. There are two large representations of such products, one being a horizontal, orange bar at the top of the matrix and other being vertical, orange bars in some of the “remote” clusters. Analyzing the products in the horizontal bar, we found that they were shipped from Amazon Global Store UK. We are unsure why such products are restricted in so many regions, especially when the same products can be shipped to these regions from amazon.co.uk, the UK Amazon storefront. The vertical bars in the “remote” region clusters can be explained similarly as the products being restricted in these regions.

There are still many unanswered questions, such as why some regions show this message versus others, such as Belarus and Russia in the sanctioned cluster, do not. However, without completely understanding the exact reasons for such distinctions, we can still use these distinctions as useful signals for clustering regions and products by various restriction motivations, including censorship or other motivations which may be more benign, such as appears to be the case for the “item cannot be shipped” products.

Censorship churn

During Phase 2, we tested all regions, including the four countries that we had previously tested in Phase 1. Since we conducted Phase 2 over four months after Phase 1, Phase 2’s experiment also provided us the opportunity to measure the amount of churn, i.e., the change in results between these experiments in those countries we measured in Phase 1. We were interested in all possible changes, including between being available versus restricted but also changes to or from having no offers, which is the ambiguous case where we cannot confidently conclude whether a product is available or restricted. Below we quickly summarize some of our observations.

Given that our Phase 1 data set consisted of products that were predominantly restricted in the four regions we tested, most of the changes were from being restricted to being some other state. While we had hoped to find evidence that Amazon had been improving their matching criteria, the evidence for that is mixed. For instance, we had found that Nietzsche’s Gay Science was censored in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia during Phase 1. This book is seemingly collateral damage of Amazon’s censorship, since the book title contains the word “gay” but its topic does not pertain to LGBTIQ issues. However, during Phase 2, the book was available in the UAE, but in Saudi Arabia the book simply shows no offers for it in the all offers display despite it having had five (censored) offers in Phase 1. This suggests that Amazon may have an additional form of censorship where it hides all offers as opposed to displaying them but not allowing them to be added to users’ carts.

We found more evidence of this phenomenon. For instance, in two cases we found that both The Joy of Sex and Witches of Pennsylvania had 29 (censored) offers to ship to the UAE in Phase 1 but had no offers to the UAE in Phase 2. It seems unlikely that, in each case, all 29 shippers independently decided to stop shipping to the UAE. Rather, these findings suggest that many censored products on Amazon may simply show no offers for them at all.

Since our methodology cannot currently distinguish such cases of censorship (versus a product organically having zero offers), it is possible that Amazon’s censorship extends beyond what we have measured. In other words, our study may be underestimating the magnitude of censorship on Amazon.

Comparing to book bans across the US

Through parent-led advocacy and state legislation, a wave of books have been banned or otherwise challenged across schools and libraries in the US. These bans have overwhelmingly targeted books that discuss themes of race, gender, and sexuality, and have disproportionately censored stories written by and about people of color and LGBTIQ people. Since the most commonly restricted product category on Amazon was books, we designed an experiment to test these banned books using our previous methodology to see which are censored and whether overlap exists between the censorship of books in US schools and libraries and the censorship of books being shipped to the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

Methodology

The nonprofit organization PEN America published a list of 3,362 instances of individual books banned, affecting 1,557 unique titles in schools and libraries across the US during the 2022–2023 school year. For each unique item in the list, we performed an advanced search on amazon.com of the book’s International Standard Book Number (ISBN). If the ISBN search failed, we would do a book search of the book’s title and the author name. Then we would follow the link in the first of the search results and, if applicable, would select paperback, or hardcover if there was no paperback button. We then saved the title of the book, the author’s name, ASIN, and URL to a file. Of the 1,557 unique titles, we were able to find 1,533 on Amazon using this method.

We implemented the above methodology programmatically using Python and the Selenium Web browser automation framework. We used the Google Books API to find the ISBN number of each book. We executed the code on February 20, 2024, on a MacBook running macOS.

Results

We ran each of the 1,533 ASINs through our Phase 1 methodology on February 21, 2024. We found 65 unique books (4%) were censored when attempting to ship them to Saudi Arabia or the UAE, with 54 of them being listed as “temporarily out of stock” and 11 as “currently unavailable”.

Censorship comparison

Similar to our Phase 1 results, Amazon censored more booked when shipped to the UAE than to Saudi Arabia. All of Saudi Arabia’s censored books were also censored in the UAE (see Table 5). As with our Phase 1 results, we found that the messaging was vague and inconsistent. The only pattern we found was that no restricted item resulted in the “this item cannot be shipped” message which is in keeping with our previous finding that this message, while used for restricting product shipments, is not used for Amazon’s political or religious censorship.

| Temporarily out of stock | Currently unavailable | This item cannot be shipped | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UAE | 54 | 11 | 0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Total unique | 54 | 11 | 0 |

Table 5: The number of books returning each availability status across each region.

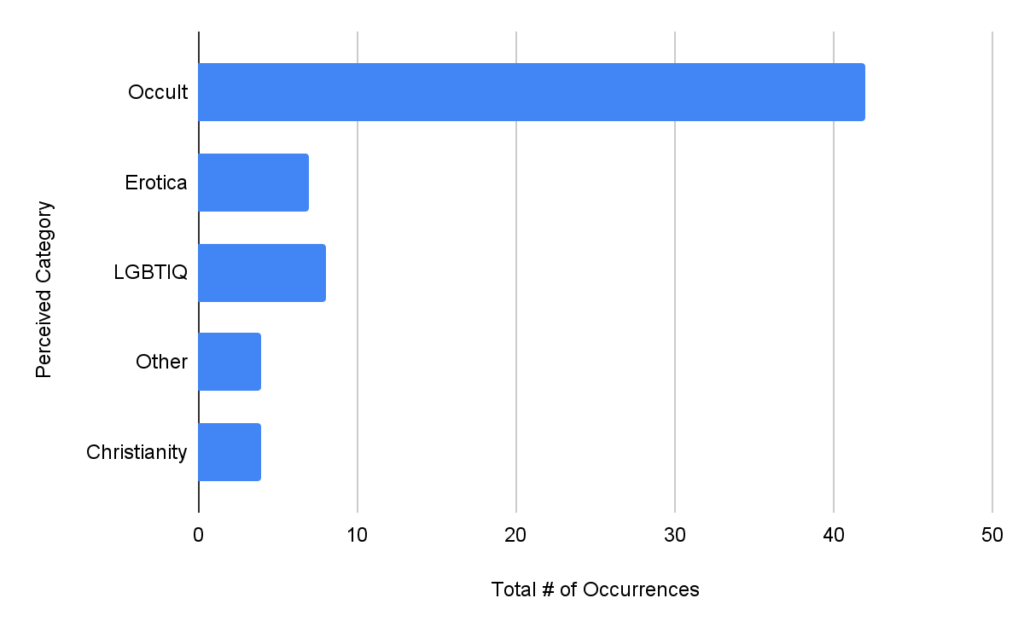

Analysis of censorship by censor motivation

To examine the motivation behind the censorship of the books we used the same method of analysis as in Phase 1. Since books tend to feature a number of themes we base this analysis on the perceived category that a censor may arrive at based on just the description and title of the book. We categorized each book into one of five categories we used previously in this report: “Occult”, “Erotica”, “LGBTIQ”, “Christianity”, or, if it did not fall into the previous four, “Other”. Figure 18 shows the proportion of censored books in each category.

We categorized all of the books based on keywords in their titles or descriptions that may have motivated Amazon to restrict the book’s shipment to the UAE or Saudi Arabia. Books that were categorized as occult largely contained words like “devil”, “demon”, and “magic” in their titles and descriptions. Books like Gender Queer and All Out: The No-Longer-Secret Stories of Queer Teens throughout the Ages were also likely censored for containing LGBTIQ content in their titles.

Comparison of motivations

PEN America’s analysis of the contents of banned books in US schools and libraries found that the top five categories of content that were challenged were violence, health and wellbeing, sexual experiences between characters, racialized characters and themes, and LGBTIQ characters and themes.

Since the motivations of the groups challenging books across the US are different from Saudi Arabian or Emirati information controls, we would expect the perceived categories of books censored to also contain differences. For instance, we found very little evidence of books being restricted for discussing race. Similarly, a number of books that were discussing health and wellness may have been perceived as erotica by Amazon for their discussions of sexual health.

However, we also found that censorship of books in the US had common motivations with Amazon’s censorship in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, specifically with books that contain LGBTIQ stories and themes, health and wellness content, and books that contain sexual content. In both cases, these books are often misrepresented as erotica or pornography. This argument has been used both by those attempting to remove books from schools and libraries, as well as by these governments when censoring the media. Organizations that advocate for book banning often use this kind of hyperbolic and misleading language to argue that they are protecting children by preventing them from accessing these books.

Additionally, another high-level commonality has to do with the censor’s lack of familiarity with the content they are censoring. As discussed above, it is unlikely that Amazon censors each book based on its content in itself. We believe that Amazon largely relies on text describing the book in the title and description to determine if a book is restricted or not in a region. Similarly, book challenges in US school libraries are often a result of a lack of familiarity with the content, with many who challenge books using excerpts taken out of context or using talking points provided by advocacy groups.

Lastly, just as censorship is legislated in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, advocacy pressure in the US has resulted in a series of state laws that enforce which books can and cannot be in schools and libraries. This state legislation has “supercharged” the work of groups organizing book bans, with 63% of book bans during the 2022–2023 school year taking place in the eight states that had enacted legislation to regulate access to books.

Limitations

In this section we enumerate and evaluate various limitations of the methodologies we employed in this report.

During our Phase 1 experiment, we derived our list of products to test from the Common Crawl dataset. This sampling of products may be more likely to include high traffic and longer-lived products. While this may even be a desirable property, there may also exist other biases introduced by sampling from the Common Crawl dataset that we have not anticipated.

During our Phase 2 experiment, our test set was derived from items that we found restricted in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. As regulatory regimes vary between countries, we suspect that other countries are very likely to have categories of restricted products not captured by this test set. China was one such country whose censorship this methodology did not capture. Therefore, while our analysis in this phase effectively compares censorship between regions of a common set of products, it cannot be interpreted as exhaustively enumerating the categories of products censored in every region.

In our testing we found that there existed some categories of product whose motivations for restricting were unclear (e.g., smartphone cases). If we had better knowledge of Amazon’s technical mechanism for filtering, we might understand such categories of products to be collateral damage of overly broad filtering rules. However, there might also exist unexplored legal or regulatory reasons for such products’ restrictions.

In our study we encountered some limitations relating to language diversity. Although our study ultimately included books in multiple languages, such as English, Japanese, and French, it notably did not encompass any Arabic books, which are critically relevant in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The lack of representation of such books may be due to a miniscule representation on the American Amazon site — amazon.com — or due to a sampling bias of Common Crawl.

Discussion

In this section we discuss how our results inform multiple high-level research questions concerning how Amazon performs censorship of products on amazon.com.

How does Amazon choose which products to censor at scale?

We found that Amazon assigned products and regions to different masterlists — which we named “baseline”, “moderate”, and “high” — that were used to restrict shipments of products to those masterlists’ regions. There are different automated methods by which Amazon could be assigning products to these masterlists or to the thematic categories (e.g., “LGBTIQ”, “Occult”, etc.) composing them. We found some words tend to commonly appear in the titles of censored products or their descriptions (e.g., “gay”, “demons”, “tarot”, etc.). This finding would support that Amazon is using a simple keyword matching approach to censoring products such as that any product with “LGBTIQ” in its title should be censored. As further evidence, Amazon censored products which coincidentally contained these keywords like Nietzsche’s Gay Science, suggesting that it was triggered by the presence of a keyword like “gay” and that Amazon had no deeper, holistic understanding of the products it evaluated.

However, we were unable to find any set of restricted keywords or other simple filtering rules that completely explain the content that we found both available and restricted. For instance, searching Amazon for books containing “gay” in the title, we did find a small number of matching paperback and hardcover books that Amazon allowed us to ship to both the UAE and Saudi Arabia. As such, if Amazon performed keyword filtering, while “gay” would seem to be a likely choice for a keyword that they would filter, we found counterexamples to such filtering suggesting that either keyword filtering is not the means through which Amazon filters products or that there are other variables in play. However, as we had also found that a small number of products could be shipped to Belarus and Russia, despite Amazon’s claim that they would cease shipping to those countries, if Amazon is intending to restrict all books with “gay” or other keywords in the title or description from being shipped to certain regions, then the same intermittent failure preventing Amazon’s categorical restriction of products being shipped to Belarus and Russia may also be affecting its restriction of other products to other regions. Thus, even if Amazon is restricting all products containing “gay” or other keywords in their titles or descriptions to certain regions, we might still expect some products to slip through their filtering.

Another possibility is that Amazon employs more sophisticated machine learning (ML) or natural language processing (NLP) methods to identify restricted products. Such filtering would also explain why a small number of products containing “gay” or “LGBT” in their title or description are not censored (e.g., as of August 14, 2024, This Book Is Gay and Not All That Glitters: An LGBT Literary Fiction Novel are available in both the UAE and Saudi Arabia). However, the few books that we found with “gay” or “LGBT” in their titles that we could ship to the UAE and Saudi Arabia featured descriptions which were openly and explicitly concerning LGBTIQ topics, and thus an ML or NLP algorithm should have restricted them regardless. These findings and our observations of false positives such as Gay Science suggest that either an ML or NLP approach is not used or that it is wholly ineffective.

In sum, while we cannot conclusively identify the exact method through which Amazon identifies products to censor, we can identify the method as being overly sensitive to the presence of certain keywords which trigger false positives.

Are these products also censored on the UAE and Saudi Arabia dedicated storefronts?

As we discussed earlier, there has been previous reporting on how Amazon censors products on the UAE Amazon site — amazon.ae. Our study does not analyze censorship on this site or the site of any other region except for the American site — amazon.com, finding that users of the American site, including Americans, are subjected to restrictions imposed by Amazon on where they can ship products. These restrictions are overly broad, and Amazon provides misleading explanations for why users cannot ship these products to different regions. Below we briefly analyze censorship on the UAE (amazon.ae) and Saudi Arabia (amazon.sa) dedicated storefronts and compare it to our findings from analyzing amazon.com.

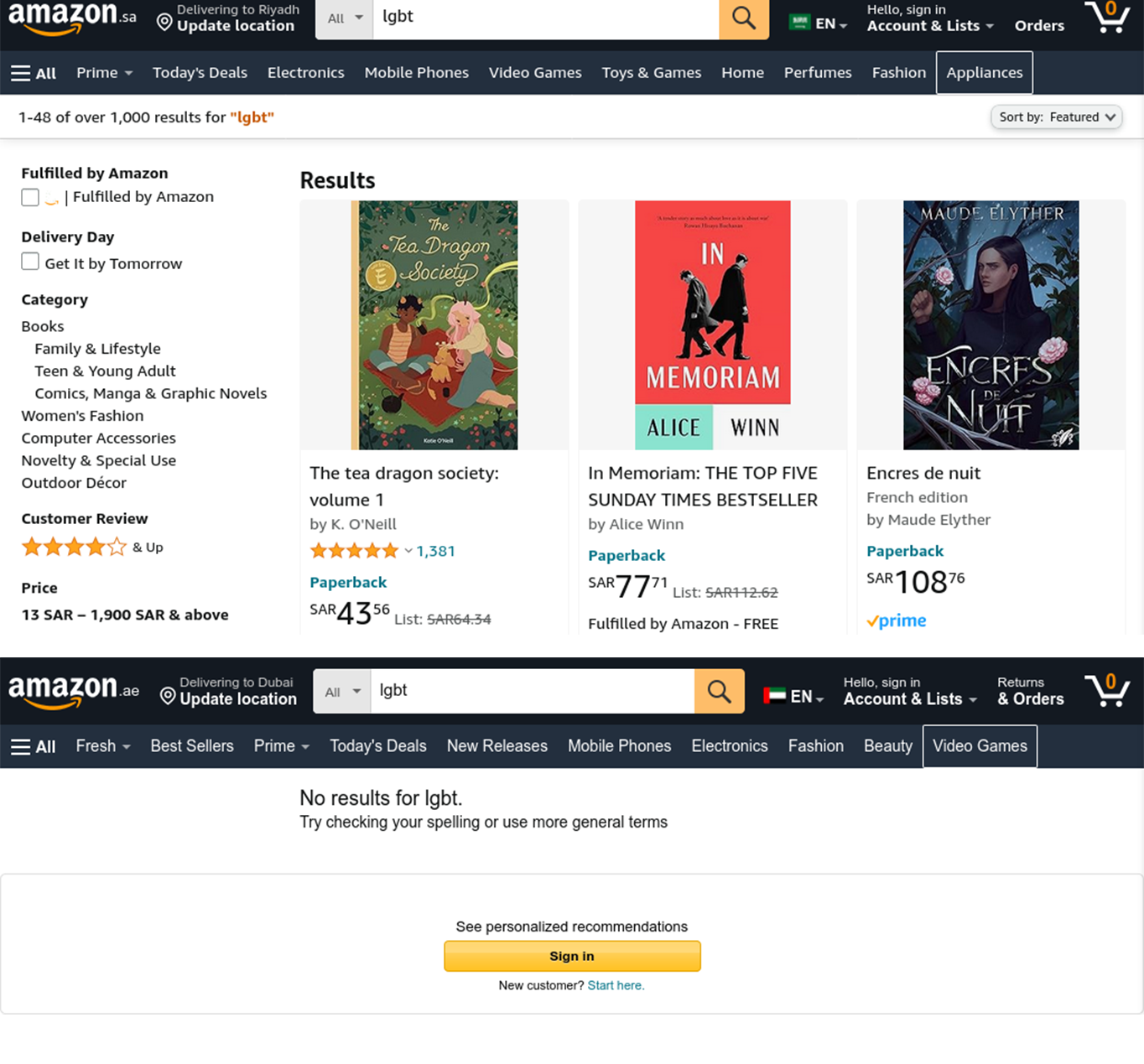

We first sought to understand if there was censorship of search queries on the UAE and Saudi Arabia regional sites. Performing search queries on the regional UAE site, we found no results for the following LGBTIQ search terms: “gay”, “lesbian”, ”transgender”, “LGBT”, “queer”, or “bisexual” (see Figure 19). Search terms related to other topics such as sexuality, the occult, or Christianity return results and are seemingly not subject to search query censorship. Thus, this censorship appears to target LGBTIQ in the UAE exclusively.

Unlike with the UAE, we did not find that the Saudi Arabia dedicated storefront performed the same type of censorship where all results for certain search queries would be censored. However, in Saudi Arabia search results for LGBTIQ topics were not relevant to our queries or, if relevant, the results did not contain the queried LGBTIQ search term. This finding may be explained by the censorship of product listings themselves on the Saudi Arabia storefront versus the additional censorship through search queries.

To explore whether and how the UAE and Saudi Arabia censor product listings, we compared the search results from Amazon’s site search and Google Search. We did this as Amazon’s search results may be censored in these regions, and Google Search provides ground truth search results. Specifically, using Google we searched for site:amazon.ae intitle:”lgbt” and site:amazon.sa intitle:”lgbt”, queries designed to return all pages from the UAE amazon.ae site and the Saudi Arabia amazon.sa sites with “lgbt” in the title.

There were five results for the UAE site: three are for products which contain either “L.G.B.T.” (LGBT with each letter followed by a period) or “L G B T” (LGBT with each letter separated by spaces) in their title. Such punctuation or spacing may be enough to evade a censorship filter on amazon.ae if it is strictly looking for the string “LGBT” without punctuation or spaces. The other two results were links to Amazon search results for “lgbt bracelet”, which, unlike searches for “lgbt” by itself, returns results, suggesting that Amazon’s amazon.ae search filter is quite naive and only filters according to strings exactly equal to restricted keywords as opposed to strings containing restricted keywords. We note though that these searches for “lgbt bracelet” do not return results for products mentioning “LGBT”. These findings suggest that, in addition to censoring search queries, the UAE regional site censors the listing of products by the presence of LGBTIQ keywords in their titles or descriptions.