Summary

- Keir Giles, a prominent expert on Russian information operations, was targeted with a sophisticated and personalized novel social engineering attack.

- The attacker took extensive measures to avoid raising Mr. Giles’ suspicions, and deceived him into creating and sending them App-Specific Passwords for his accounts, bypassing Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA).

- Google later spotted and blocked the attacker. Their Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) labels the operator Russian state-backed UNC6293, which they link with low confidence to APT29, which is attributed to Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR).

- We expect more social engineering attacks leveraging App-Specific Passwords in the future.

Click here to read Google’s blog post on this campaign.

Introduction: New Pressures on Attackers

In recent years, users’ familiarity with common phishing tactics, increasingly advanced detection and blocking by platforms, and the rise in use of Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), have all contributed to changes in the ways that attackers phish accounts. The introduction of more secure forms of MFA, such as hardware security keys, has also closed off certain avenues of social engineering.

These pressures, among others, are driving attackers towards more complex social-engineering tactics, and more technically sophisticated attack frameworks, including targeting MFA. For example, a recent analysis by Cisco’s Talos reported that nearly half of all recent incidents that their team responded to involved attackers trying to bypass MFA.

As past reporting highlights, attackers need to improve their technical methods, and adapt their social engineering approaches to bypass both platform detections, as well as avoid the subtle cues associated with phishing attempts that many users have now been trained to spot.

Looking for a Side Door

While many state-backed attackers still focus on phishing a target’s passwords and MFA codes, others are constantly experimenting with novel ways to access accounts. Often, these efforts involve blending social engineering and targeting alternate account access flows, such as access tokens. Attackers have also gravitated towards cross-platform attacks, where initial outreach may happen on one messaging platform (e.g. Signal or WhatsApp), and later move to another channel, such as email. These attacks split attack elements between different ecosystems, making it more challenging for platforms and defenders to put the pieces together.

Volexity recently reported on several such efforts, and the Citizen Lab has also tracked similar attacks against civil society groups in the course of our investigations of Russian state-sponsored groups.

The attack described in this research note is yet another effort to gain account access through a novel method: convincing the target user to create and share a screenshot of an App-Specific Password (ASP).

| What are App-Specific Passwords?

Certain applications do not support Multi-Factor authentication, or are otherwise incompatible with platforms’ standard login workflows. In order to allow these apps to access online accounts with MFA enabled, a user can create an App-Specific Password (ASP). For example, a user might add an ASP to allow a legacy third-party mail client access to their email account. Google refers to these apps as Less Secure Apps (LSAs) and has been phasing out support in Google Workspaces; however Google still allows users to create and remove these passwords on their personal Gmail accounts. |

Enter the App-Specific Password Attack

Keir Giles is a well-known and outspoken academic expert on countering Russian information and influence operations and the Russian military. He is a senior associate of the Russia programme at Chatham House, a UK-based policy institute, and his work has uncovered covert Russian campaigns. He has also written extensively on Russia’s actions following their invasion of Ukraine. Mr. Giles contacted the Citizen Lab for assistance with the attack, and we are publishing this note with his consent.

The Attack Begins

On May 22, 2025, a sender purporting to be U.S. State Department official “Claudie S. Weber” sent an email to Mr. Giles. The message purports to be an invitation for a consultation, something that would be common for him to receive.

We could find no evidence that “Claudie S. Weber” exists or is a U.S. State Department employee. The attacker used a Gmail account for the entire interaction:

However, four emails at @state.gov are also included on the CC line, including a “Claudie S. Weber” @state.gov email address. This lends to the perceived credibility and safety of the email exchange.

A target might reason “if this isn’t legitimate, surely one of these State Department employees would say something, especially if I reply and keep them on the CC line.”

In fact, the attacker has likely created fictitious personas and @state.gov email addresses purely as a credibility signal. We believe that the attacker is aware that the State Department’s email server is apparently configured to accept all messages and does not emit a ‘bounce’ response even when the address does not exist.

The message’s English is grammatical and fluent, but somewhat generic in tone, raising the possibility that the attacker used a large language model (LLM) or similar tools to help craft the outreach. The message was also received within Washington D.C. working hours, adding an additional element of credibility.

Setting the Stage

The message content, timing, and inclusion of official .gov email addresses in the CC field combined to create the appearance of a safe and credible approach. Mr. Giles described these techniques to us as establishing “pillars of plausibility.”

Mr. Giles responded to the message indicating interest, but noted that the date might not work for him. The attacker responded, introducing the core deception: inviting him to join the State Department’s “MS DoS Guest Tenant” platform.

As the conversation unfolded (ultimately involving at least 10 exchanges), the attacker sent a PDF file with instructions to register for an “MS DoS Guest Tenant” account.

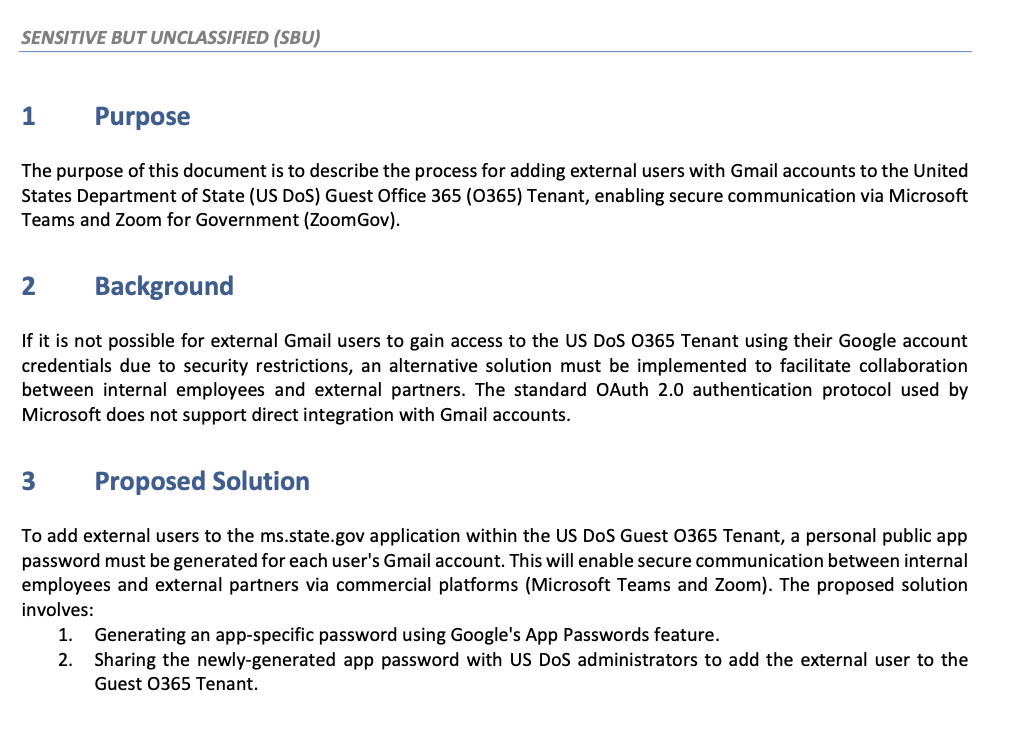

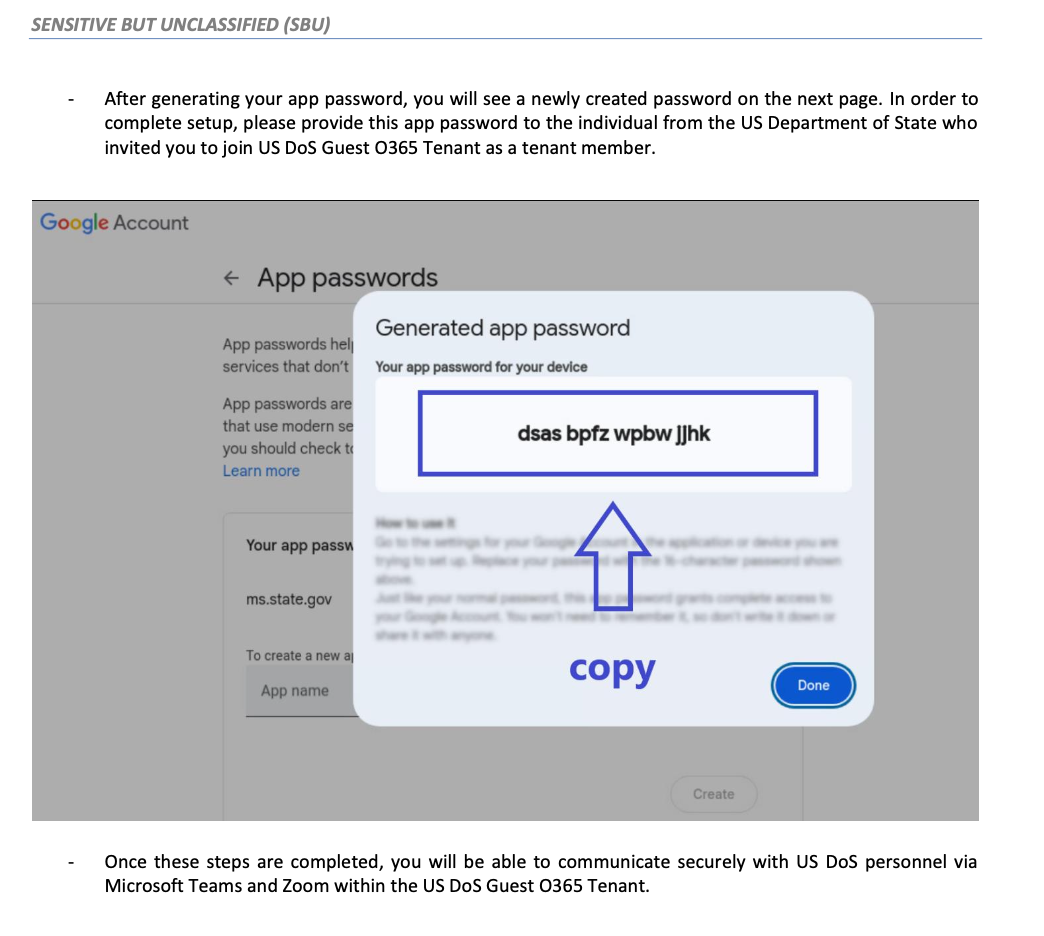

The PDF appears to be an official document with markings and revision history. It walks the target through the creation of an App-Specific Password on a Google email account.

The document does not appear to have any of the telltale errors of language, grammar issues or other mistakes that characterize many previous generations of lure documents used by state-backed attackers.

The instructions PDF (note, this file does not contain malware):SHA256: 329fda9939930e504f47d30834d769b30ebeaced7d73f3c1aadd0e48320d6b39 |

Getting the Target to Create and Share an App-Specific Password

This attack hinged on deceiving Mr. Giles into believing that, by creating and sharing an App-Specific Password (ASP), he would gain access to a secure government resource enabling him to participate in the consultation.

To establish the deception, the attacker sought to persuade Mr. Giles that he was following in a process of “adding your work account… to our MS DoS Guest Tenant platform.” The document and emails outlined the procedure: creating an ASP to “enable secure communications between internal employees and external partners.”

Logic of the Deception

| What you think is happening | What is actually happening |

| You are creating and sharing an App-Specific Password to access a “secure” State Department resource. | You are creating and sharing an ASP credential that gives the attacker full access to your account. |

The attackers skillfully reframed creating and sending them an ASP as creating and sharing a code to obtain access to an application maintained by the State Department. In reality, of course, the ASP would provide them complete and persistent access to his accounts.

The workflow has many aspects designed to enhance plausibility, especially for a user unfamiliar with how App-Specific passwords work. For example, the attacker instructed Mr. Giles to enter “ms.state.gov” into the “App name” field of Gmail’s App passwords page. In the context of the deception, the goal was to deceive him into believing that he was adding an official state.gov application. In fact, the “ms.state.gov” text is meaningless beyond furthering the ruse. Adding the text merely creates a label for the ASP that was viewable only to him in a field that accepts arbitrary text.

Flexible Attackers: Ensuring the Compromise

One factor that Mr. Giles cites as helping to preserve the credibility of the deception is what he describes as its “unhurried pacing.” Indeed, the interaction unfolded over more than 10 exchanges across several weeks, indicating substantial patience on the part of the attacker.

The attackers were also ready with answers and prepared to adapt in response to Mr. Giles’ replies. For example, after Mr. Giles stated that the initially proposed time would not work, the attackers chose to not explicitly add pressure or urgency, instead suggesting that they set up the platform for the future.

Meanwhile, when Mr. Giles managed to follow the procedure with a separate account that he had access to, the attackers then nudged him towards performing the same procedure on the accounts that they were presumably targeting.

“…I’ve consulted with our IT Team once more regarding the registration issue, and they would like me to ask if you could provide some additional information to help troubleshoot further. Specifically, they need screenshots of what you see when accessing:

Please send these screenshots from both your work and personal accounts….” |

Figure 6. The attacker’s message to Mr. Giles when he encountered difficulty in accessing Google’s ASP console for specific accounts. The attackers provided him with links to check and requested screenshots, enlisting him in troubleshooting the social engineering.

Similarly, when Mr. Giles initially experienced some difficulties in creating ASPs, the attackers worked with him to ensure that he was able to successfully create them, as shown in the excerpted exchange in Figure 6.

Attack Impact

This was a highly sophisticated attack, requiring the preparation of a range of fake identities, accounts, materials and elements of deception. The attacker was clearly meticulous, to the extent that even a vigilant user would be unlikely to spot out-of-place elements or details.

Ultimately, Mr. Giles’ was successfully socially engineered into creating and providing the attacker with several ASPs on multiple accounts. Google later identified the attack, locked down the impacted accounts, and disabled the attacker email.

Mr. Giles, upon recovering his accounts and inspecting his account activity logs, found a notification indicating a suspicious login attempt on one of his accounts on June 4, 2025, associated with the following Digital Ocean IP:

178.62.47[.]109 |

Mr. Giles has publicly shared his suspicion that the material exfiltrated from his accounts is likely to be manipulated and selectively released as part of a future information operation. This seems likely based on the identity of the attacker, and their long track record of similar operations. Such information operations often bury falsehoods in forests of facts, adding credibility to misleading narratives.

Google’s Response

The Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) published a blog post that identifies this attacker as the Russian state-sponsored actor UNC6293, and they make a low-confidence association to APT29 / ICECAP (historically known as “Cozy Bear”).

Beyond the attack on Mr. Giles, GTIG has identified a second campaign by UNC6293 leveraging the same tactics, including Ukrainian themes.

We note that GTIG’s blog post contains additional indicators associated with a residential proxy used by the attackers.

Protecting Yourself and Your Organization

App-Specific Passwords can provide value to users, but as UNC6293 has figured out, they can also be leveraged for account compromises like the case described here. While certain security risks of ASPs are known, we have not previously investigated a social-engineering attack targeting them. However, many services similar to Gmail also support ASPs (including Apple ID accounts), and we expect that future attacks are likely to attempt similar ruses.

Use Google’s Advanced Protection Program

Everyone should use Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) on every account where it is available. However, some people are at greater risk of being targeted. This especially applies to individuals and organizations in civil society, particularly those working on or around conflicts, litigation, advocacy, and other high-profile topics. For these individuals, who are at greater risk because of who they are or what they do, we recommend enrolling in Google’s Advanced Protection Program. We think this program would help block similar attacks to what we described here.

Be Mindful of Changing Social-Engineering Tactics

Attackers are constantly adjusting their tactics. In this attack, for example, the unhurried pace of the conversation, the responsive back and forth communications, and the presence of other .gov emails on the CC line all deviated from what many users typically expect from phishing emails. This illustrates the lengths a sophisticated attacker may go to compromise a high-value target.

We urge everyone to exercise caution when reading an unsolicited email or message. Whenever you find yourself in an exchange that asks you to share information from your account, or modify settings, make sure you know who you are communicating with. One of the best ways to do this is to verify the communication ‘out-of-band’ (e.g. with a phone call to a person’s workplace) before moving forward.

Security Teams: Watch Out for ASPs

For organizations, we recommend ensuring that you are aware of the services where users may enable ASPs, and ensure that they are disabled unless needed for specific users or use cases. Adding education about ASPs to user security programs, including the implications for personal accounts, will likely be helpful.

For organizations that use Google Workspaces, progress is being made to improve user security. Google is clearly aware of the risks from ASPs and LSAs, and in Google Workspaces has implemented a plan to phase them out in a process that was first announced in 2019.

Google’s choice to phase out ASPs for Less Secure Apps (LSAs) on Google Workspaces is a sensible measure. We recognize that for regular Gmail users, Google may still be seeking to balance security with the diversity of LSAs on which their global userbase still depends. Thus, the risk continues for regular Gmail users who may be tricked by similar campaigns.

Recommendations for Providers

Attackers constantly learn from each other, and while this is the first case of ASP-social engineering we have seen, it is unlikely to be the last.

Google caught this attack and locked down Mr. Giles’ accounts, notifying him that they had identified suspicious activity. We believe that adding additional warning text or an explanatory interstitial on the “App passwords” page alerting users of the possibility that attackers may target ASPs would be helpful. We suggest that other providers that offer ASPs consider taking similar steps.

We also think it would be useful for users to be regularly nudged about whether their accounts have any ASPs enabled, as well as potentially adding a visible approval step once the first connection is made using a new ASP.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Giles for his extraordinarily gracious willingness to share the material of this attack and describe how he experienced it. When targets elect to speak out and share their experiences, it helps make us all safer.

Special thanks to Alyson Bruce for editorial and graphics support, and Ksenia Ermoshina, Alberto Fittarelli, Micah Lee, Cooper Quintin, M Scott, and Adam Senft for review.

Special thanks to the Google Threat Intelligence Group.

Research for this project was supervised by Professor Ronald J. Deibert.