Eritrea

The Eritrean government has a long history of controlling its nationals abroad and using them for keeping the regime in power. Eritrea’s diaspora has grown through different waves of emigration during the three-decade-long armed struggle for independence and the war against Ethiopia. This exodus has also been triggered by the introduction of the open-ended mandatory national service in 2002 under the increasingly autocratic rule of President Isaias Afewerki and the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ).

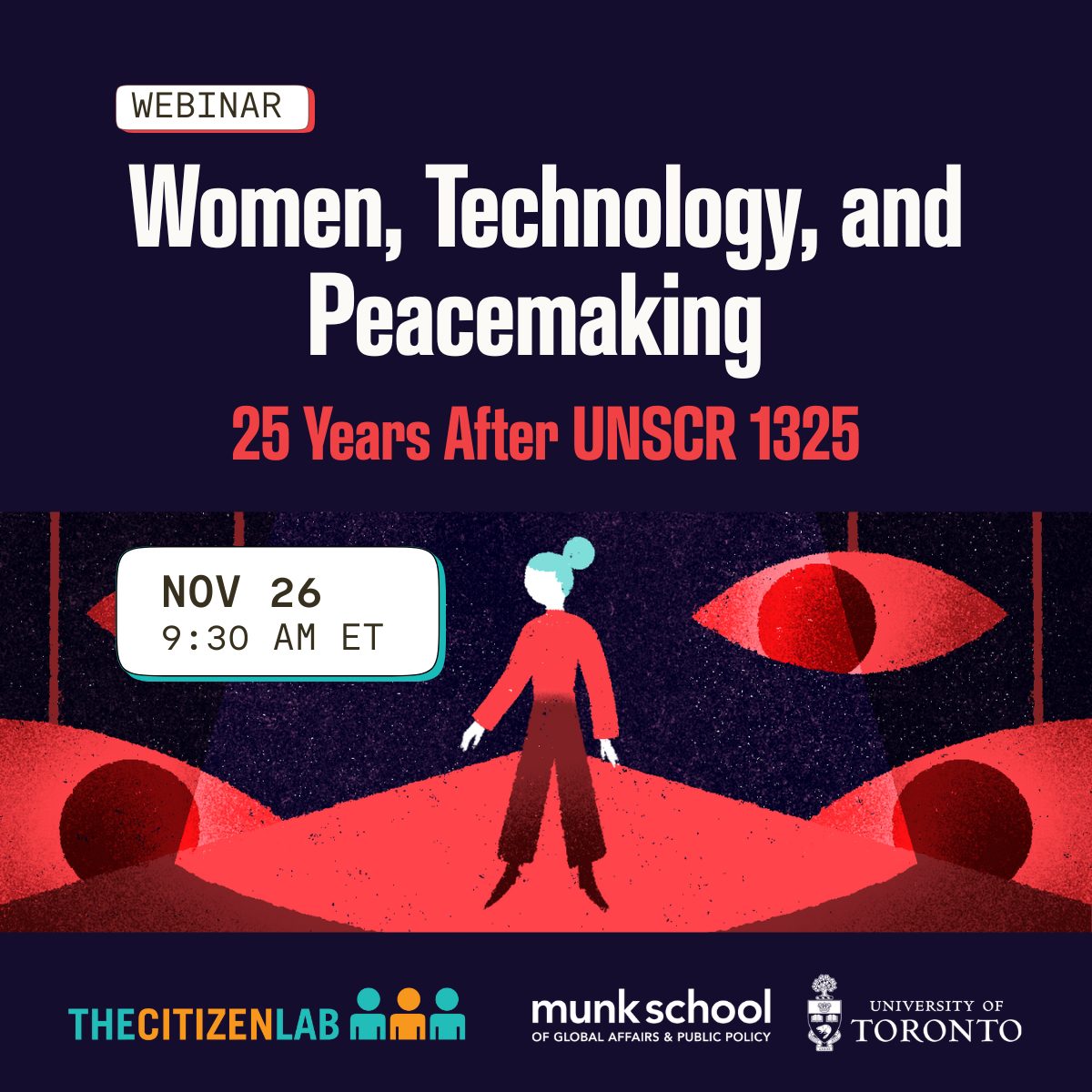

This country spotlight is part of the Citizen Lab’s research on digital transnational repression. Digital transnational repression arises when governments use digital technologies to surveil, intimidate and silence exiled dissidents and diaspora communities. It is part of the broader practice of transnational repression, which refers to states using methods such as harassment, coercion-by-proxy, kidnapping, and assassination attempts, in order to control dissent outside their territories. Further research by the Citizen Lab on this issue – including research reports, country spotlights, stories of digital transnational repression, video interviews, and academic articles – is available here .

The Eritrean government has a long history of controlling its nationals abroad and using them for keeping the regime in power. Eritrea’s diaspora has grown through different waves of emigration during the three-decade-long armed struggle for independence and the war against Ethiopia. This exodus has also been triggered by the introduction of the open-ended mandatory national service in 2002 under the increasingly autocratic rule of President Isaias Afewerki and the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ). With more than one third of its nationals living outside the country, Eritrea has one of the largest diasporas in the world compared to the size of its population. The government regards all Eritreans as its nationals, even if they have acquired another citizenship or were born abroad.1

Donations from Eritrea’s diaspora helped sustain the liberation movement. After independence, the government institutionalized a ‘diaspora tax’ requiring every Eritrean national abroad to pay two percent of their income to the state. Diplomatic missions and affiliated community organizations serve as outposts for enforcing tax collection. All kinds of administrative and consular services depend on the payment of this tax and Eritreans are forced to pay it retroactively whenever they need paperwork for passport extensions, inheritance cases or even the burial of deceased relatives.2 In addition to taxation, the government exploits the diaspora’s feelings of obligation toward their extended family in Eritrea by letting them financially sustain relatives who often suffer under the country’s dire economic situation. Remittances of the diaspora constitute a significant percentage of the government’s income and its largest source of foreign currency.3

In 2004, the government established the Young PFDJ as a youth organization for its diaspora. Its local chapters, located in numerous host countries, shore up support for the government and raise funds in cultural festivals and national anniversaries. Through pressure from other diaspora members and harassment of relatives in Eritrea, people are coerced to participate in these events or volunteer in government-friendly diaspora associations. Various forms of media propaganda aim to uphold national pride and cohesion among the diaspora, perpetuating the official narrative of a heroic nation resisting foreign adversaries.4 With increasing resistance to the collection of the two-percent tax and demanded allegiance to the home state, especially among younger generations, the government has stepped up efforts to indoctrinate, control, and mobilize its nationals abroad.5

As civic space and freedom of expression inside Eritrea remain severely curtailed, the diaspora is becoming more politicized. In recent years, events organized by embassies and pro-government associations have turned into sites of violent clashes between government supporters and detractors in countries such as the U.K., Germany, Sweden, Israel, Canada, and the U.S. In a more radical rejection of the government, groups of recent emigrants and second generation diaspora Eritreans are attempting to unify and rally the opposition in exile under initiatives like the “Blue Revolution.”6

To maintain its grip over the diaspora, the Eritrean government relies on different methods of transnational repression, including physical assaults, harassment, surveillance, intimidation, character assassination, and the refusal of consular services. In neighboring countries like Kenya and South Sudan, Eritrea has used passport cancellations and the manipulation of local authorities to get hold of dissenters. In Europe and North America, the government exercises coercion and control primarily through embassies and loyalist networks.7 In Germany, for example, government supporters visited migrant shelters to urge refugees to pay the diaspora tax and government-friendly interpreters tried to manipulate interviews during asylum procedures.8 Extensive monitoring and infiltrations by government informants has created a culture of mistrust and suspicion.9

The polarization of the diaspora and government attempts to suppress dissent among Eritreans abroad also play out on social media. Aggressive online trolling and bullying have become a permanent feature of Eritrean diaspora online networks and social media.10 Online threats against activists and journalists criticizing the government include gendered and sexualised abuse against women human rights advocates.11 Government critics and opposition members are often framed as traitors and ostracized through smear campaigns, while their families in Eritrea are being harassed and threatened. These campaigns are instigated by government members, such as ambassadors, as well as the broader loyal diaspora.12

Our interviews reflected these and similar tactics to intimidate and discredit women human rights defenders in the diaspora. An activist in the U.K. was insulted as a “white man’s whore” because of her work for an international human rights organization. An online mob even started a campaign to get her fired, pushing out a dedicated hashtag on Twitter and emailing her director. There were online threats to find her and she had to endure harassment in public events. In one unsettling episode an Eritrean man who had stalked her on social media showed up at a protest and threatened her.

Other Eritrean research participants shared similar experiences. They were exposed to threats and smear campaigns from pro-government online networks who undergirded their attacks with sexualised insults and macho slurs. A journalist and human rights activist who advocated against the mandatory national service in Eritrea faced a massive backlash from government supporters threatening to find out where she lived and do something to her children. The attackers also told her that as a woman she should not mingle in political debates. “They would write things like: what do you know?! Sit home and breastfeed your kids!”

For these women, the constant aggression in response to their social media presence was even more disturbing because, like them, most assailants were living abroad, often in the same country and possibly even the same neighborhood. They described navigating the fault lines running through this divided community as exhausting and claustrophobic. One activist who had been repeatedly harassed in public said she would rather go to an Ethiopian restaurant to enjoy Injera, the traditional flatbread eaten in both countries. Whenever she met other Eritreans she would never know “if they hate or support me.”

- Nicole Hirt and Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad (2017), “By Way of Patriotism, Coercion, or Instrumentalization: How the Eritrean Regime Makes Use of the Diaspora to Stabilize Its Rule,” Globalizations 15(2). ↩︎

- Aaron Berhane and Vappu Tyyskä (2017), “Coercive Transnational Governance and Its Impact on the Settlement Process of Eritrean Refugees in Canada,” Refuge 33(2). ↩︎

- Emanuela Dalmasso, Adele Del Sordi, Marlies Glasius, Nicole Hirt, Marcus Michaelsen, Abdulkader S. Mohammad, and Dana Moss (2018), “Intervention: Extraterritorial Authoritarian Power,” Political Geography 64. ↩︎

- Nicole Hirt (2020), “The Long Arm of the Regime — Eritrea and Its Diaspora,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung <https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/regionalprofile/english-version-country-profiles/305657/the-long-arm-of-the-regime-eritrea-and-its-diaspora/#footnote-target-19>. ↩︎

- Nicole Hirt (2023), “‘My Parents Told Me to Love My Country’: Positionalities of Second-Generation Diaspora Eritreans in a Transnational Setting,” Globalizations. ↩︎

- BBC (2024), “Why Eritreans are at War with Each Other Around the World,”(May 23) <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cw884l2wld8o>. ↩︎

- Amnesty International (2019), “Eritrea: Repression Without Borders,” Amnesty International <https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AFR6405422019ENGLISH.pdf>. ↩︎

- Freedom House (2022), “Germany: Transnational Repression Host Country Case Study,” <https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/germany>. ↩︎

- David Bozzini (2015), “The Fines and the Spies: Fears of State Surveillance in Eritrea and in the Diaspora,” Social Analysis 59(4). ↩︎

- Victoria Bernal (2023), “Crazy, Stupid, Lying, Traitors: Eritrean Politics and Extreme Speech Online,” Anthropological Quarterly 96(4). ↩︎

- UN Human Rights Council (2024), “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Eritrea, Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker,” <https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g24/073/00/pdf/g2407300.pdf> ↩︎

- Maeve Shearlaw (2015), “From Online Trolling to Death Threats – The War to Defend Eritrea’s Reputation,” The Guardian (August 18) <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/aug/18/eritrea-death-threats-tolls-united-nations-social-media>. ↩︎