Meryem

A Human Rights Activist From Xinjiang, China

Meryem and her family left the Xinjiang region in China for Turkey in the early 1990s, before settling in North America. As a human rights defender, Meryem has experienced various digital threats in response to her activism. She is frequently attacked by what she believes to be Chinese state-backed trolls on X, Facebook, and in the comment section on public Zoom meetings.

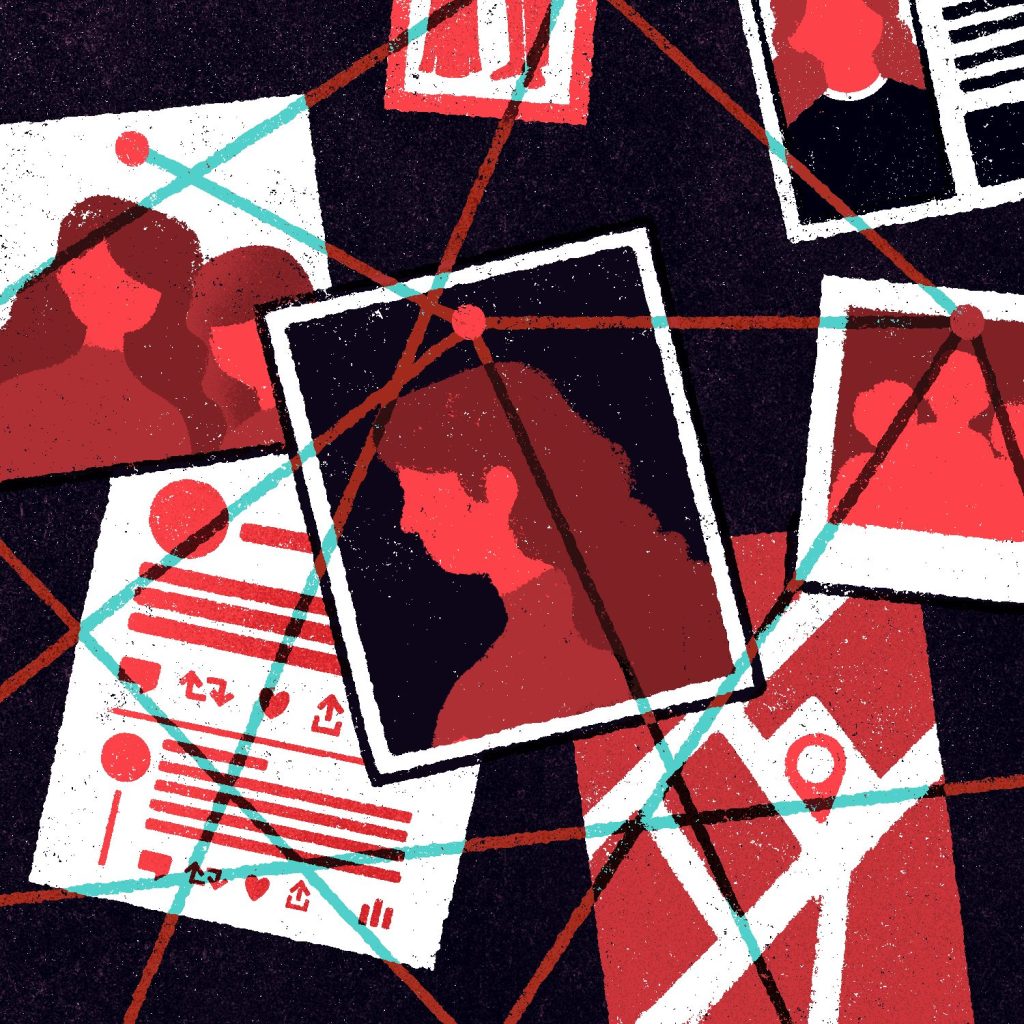

This country spotlight is part of the Citizen Lab’s research on digital transnational repression. Digital transnational repression arises when governments use digital technologies to surveil, intimidate and silence exiled dissidents and diaspora communities. It is part of the broader practice of transnational repression, which refers to states using methods such as harassment, coercion-by-proxy, kidnapping, and assassination attempts, in order to control dissent outside their territories. Further research by the Citizen Lab on this issue – including research reports, country spotlights, stories of digital transnational repression, video interviews, and academic articles – is available here .

Meryem and her family left the Xinjiang region in China for Turkey in the early 1990s, before settling in North America. As a child, Meryem’s first exposure to the Chinese government’s attempts to tightly control information about the rapidly intensifying oppression of the Uyghur culture and community in northwestern China was from family members engaged in human rights journalism. This instilled in her a determination to advocate for her homeland and people. She now works as a human rights defender in a nongovernmental organization.

Meryem has experienced various digital threats in response to her activism. She is frequently attacked by what she believes to be Chinese state-backed trolls on X, Facebook, and in the comment section on public Zoom meetings. Meryem’s home address was posted on these platforms and, in turn, she received waves of threatening and hostile messages. She tried to mitigate the impacts of this type of harassment by turning off the comment section during virtual events. Unfortunately, while this approach blocks trolls, it also prohibits engagement with genuine participants who are interested in her activism work.

Offline threats and harassment have caused Meryem “reputational and psychological harm.” For example, Meryem explains that Chinese government supporters attend Uyghur human rights conferences with the intent to humiliate, discredit, and shame her work. Meryem says that because she is a woman, perpetrators believe her activism is less impactful than a man’s activism. But Meryem responds to these perpetrators by explaining that “I am being attacked […] because I am speaking the truth […] no matter what my gender is.” Meryem knows she sacrifices her safety, but she will not let anyone stop her from being an activist.

Still, Meryem’s wellbeing is compromised by the Chinese government’s online harassment. She explains that, despite being an optimistic person, she suffered a panic attack because of the surveillance tactics launched against her. Meryem also experiences paranoia, engages in self-censorship, and refrains from communicating with friends and family members to “limit the information accessible to the attackers.” In the face of constant online harassment, Meryem tries to stay positive by telling herself, “maybe I scared them, that’s why they want to scare me.” But more tangible action is needed. Meryem calls on social media platforms to better identify authoritarian-regime backed accounts that perpetrate gender-based digital transnational repression so they can be reported and blocked.