Update on Information Controls in Burma

Crossposted from the OpenNet Initiative blog

After years spent as one of the world’s most strictly controlled information environments, the government of Burma (Myanmar) has recently begun to open up access to previously censored online content. Independent and foreign news sites, oppositional political content, and sites with content relating to human rights and political reform — all previously blocked — have recently become accessible. These developments have occurred as part of a broader process of political and economic liberalization currently underway in this historically strict authoritarian state.

This brief outlines the changes in information controls that have occurred during the past year and reports the results of recent OpenNet Initiative tests for Internet filtering in the country. While significant censorship of a number of types of online content persists in the country, the past year has seen a notable decrease in both the breadth and depth of filtered content.

Recent developments in Burma

Following decades of military rule, Burma has undergone a series of significant political and economic reforms since elections in November 2010. March 2011 saw the end of formal military rule in the country, with reformist Thein Sein becoming the country’s first civilian president in half a century. While by-elections held in April 2012 included numerous reports of fraud, the opposition National League for Democracy, including leader and Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, won seats after contesting their first elections since 19901. The past year has also seen the release of hundreds of political prisoners and legislative changes re-establishing labour rights in the country2.

Reforms have also extended to the country’s strict information control regime. Beginning in September 2011, reports from the country indicated that the historically pervasive levels of Internet censorship had been significantly reduced. International news sites, including Voice of America, BBC, and Radio Free Asia, long blocked by Burmese censors, had become accessible overnight.3 Reports from Voice of America seemed to confirm this accessibility, as the organization observed a significant increase in visits to their Burmese-language news service beginning in September 2011.4 Reports also indicated that a number of previously censored independent Burma-focused news sites which have been highly critical of Burma’s ruling regime, such as the Democratic Voice of Burma and Irrawaddy, were suddenly accessible.5 Following the reduction in online censorship, the head of Burma’s press censorship department described such censorship as “not in harmony with democratic practices” and a practice that “should be abolished in the near future.”6

In August 2012, the Burmese Press Scrutiny and Registration Department announced that all pre-publication censorship of the press was to be discontinued, such that articles dealing with religion and politics would no longer require review by the government before publication.7 Restrictions on content deemed harmful to state security, however, remained in place.8 In a September 2012 speech to the United Nations General Assembly, Burmese President Thein Sein described the country as having taken “irreversible steps” towards democracy, a speech broadcast on state television for the first time.9

Previous ONI research in Burma

ONI conducts technical testing of Internet filtering using specially designed software distributed to researchers located in the country of interest.10 ONI has conducted testing for Internet filtering in Burma each year since 2005. Prior to 2012, all instances of testing in Burma found pervasive blocking of web content, particularly critical political content, Burmese opposition websites, and independent media sites:

- ONI’s earliest testing in 2005 on the ISP Bagan Cybertech found widespread blocking of critical political content, email service providers, and pornography.11 Also found blocked were sites dedicated to the indigenous Karen people (http://www.karen.org), sites related to pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi (http://www.dassk.com), and independent news media (http://www.irrawaddy.org). At the time of testing in 2005, filtering in Burma was implemented through the use of software from the U.S. company Fortinet.

- Testing conducted in 2006/2007 on ISPs Myanmar Teleport (MMT, formerly Bagan Cybertech) and Myanmar Posts and Telecom (MPT) obtained similar results to past rounds of testing. Testing found significant disparity in the breadth and depth of content filtered between the two ISPs.12 MMT’s filtering focused almost exclusively on sites with links to Burma, while MPT filtered a broader range of international content.

- Testing conducted on MMT and MPT in 2008 and 2009 found a continuation of this pattern of filtering.13 A substantial number of blogging platforms and news websites were blocked, as were circumvention and anonymizer tools and the website of VoIP provider Skype. The two ISPs tested were also found to vary in the granularity of their blocking, with MMT found to block entire domains of sensitive content while MPT was found to block the specific URL of filtered content.

- Testing conducted in 2010 on ISPs Yatanarpon Teleport (formerly MMT, Bagan Cybertech) and MPT found similar results.14 Yatanarpon was found to block a number of media sharing and social media sites, including YouTube, Flickr, and Twitter. Users who attempted to access blocked content on both of these ISPs were presented with a block page identifying the content as blocked.

- Research conducted in 2011 by the Citizen Lab documented the use in Burma of commercial filtering products manufactured by U.S.-based Blue Coat Systems.15

Other forms of information controls beyond Internet filtering have also been extensively documented in Burma. The most extreme example of such information controls occurred in 2007, when Burma’s international Internet connectivity was completely severed for two weeks following the government’s violent crackdown on widespread protests.16 In addition to restricting opportunities for social mobilization, the Internet shutdown was widely viewed as a means of preventing videos, photographs, and news reports documenting the violent protests from reaching beyond Burma’s borders.17 Other forms of information disruptions documented in Burma include website defacement and DDoS attacks against independent media websites on the anniversaries of the 2007 protests18 and the 8888 uprising.19 In the lead-up to the country’s 2010 general elections, a massive DDoS attack against MPT, Burma’s main Internet provider, effectively severed the country’s international connectivity for a second time.20

Combined with strict regulations on information distribution, slow connection speeds, and the extremely low levels of Internet penetration in Burma, this extensive record of information control prior to 2012 reflected a highly restricted and limited information space.

2012 ONI testing results

ONI conducted testing in Burma from August 4 to 19, 2012 on the ISP Yatanarpon Teleport. The results of these tests showed that both the scope and depth of content found to be filtered were drastically reduced compared to all previous rounds of ONI testing dating back to 2005. From a total of 1,500 URLs tested, only 132 were found to be blocked. A full list of blocked URLs, as well a lists of URLs tested, can be found in the ‘Data’ section below.

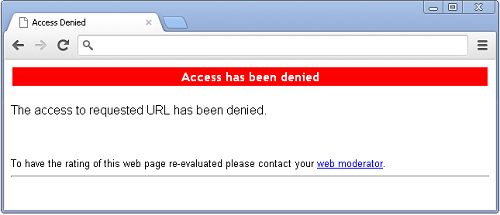

Testing showed that ISPs in Burma block content with an explicit blockpage indicating that the requested content is blocked and offering an email address to request the re-evaluation of the categorization of the page. The block page identified during ONI’s 2012 round of testing can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Block page seen on Yatanarpon Teleport when attempting to access restricted content in August 2012. (Click image to enlarge)

Almost all of the URLs found blocked belonged to ONI’s “Social” category.21 Pornography was still widely blocked, as was content relating to alcohol and drugs. Out of 132 total URLs found blocked, 104 belonged to the pornography and alcohol and drugs category. Also found blocked were gambling websites, online dating sites, sex education, and gay and lesbian content. A number of sites categorized as “Internet Tools” were also found blocked, including web censorship circumvention tools like Proxify (http://www.proxify.com) and filesharing services like the recently closed BTJunkie (http://btjunkie.org).

In contrast to past ONI testing, however, only a very small number of websites belonging to ONI’s “Political” category were found to be blocked.22 Almost all of the websites of opposition political parties, critical political content, and independent news sites previously found to be blocked were found to be accessible during 2012 testing. Only 5 of the 541 tested URLs categorized as political content were found to be blocked:

- “Kwe Ka Lu” (http://www.kwekalu.net/), a news site with content relating to the minority Karen group

- “Myanmar Cartoons and Entertainment News” (http://www.myanmartoons.4-all.org)

- “We Fight We Win” (http://komoethee.blogspot.com), a critical political blog

- “Freedom isn’t free” (http://www.niknayman-niknayman.co.cc), also a critical political blog

- Exit International (http://www.exitinternational.net), an Australia-based euthanasia advocacy organization

It is not clear why these sites remain blocked despite the significant decrease in filtering of other political content.

Conclusion

Since ONI began testing for Internet filtering in 2002, the practice has become a de facto global norm, with over 40 countries found to have engaged in filtering of online content. The changes seen in Burma, while still fragile, represent a rare decrease in the level of Internet filtering. While Burma remains a significant censor of a number of content categories, it has demonstrated a marked decrease in filtering of news and oppositional political content. The country has loosened a number of media restrictions, and its leadership openly discusses the end of censorship. While Burma’s reform process may be in its early stages, the country has taken steps toward opening up its information environment. ONI will continue to monitor freedom of expression issues in Burma in the months to come.

Acknowledgements

The OpenNet Initiative would like to thank an anonymous individual for generous assistance in collecting technical data from Burma.

Data

The complete list of blocked URLs, as well as the lists of URLs tested, can be found here:

Complete list of blocked sites on Yatanarpon

- [CSV] [Google Doc]

- Testing conducted from August 4 to 19, 2012

- Category codes can be found in Google Doc version

List of URLs tested in Burma

- Local List [CSV] [Google Doc]

- Global List [CSV] [Google Doc]

- Lists used in testing conducted from August 4 to 19, 2012

- Category codes can be found in Google Doc version

Important note about testing data: The absence of a particular URL from any of the lists of blocked URLs is not necessarily an indication that the content is accessible in Burma. In some circumstances, issues encountered during data collection prevent confirmation of the status of a given URL.

Footnotes:

1BBC, “Burma’s Aung San Suu Kyi wins by-election: NLD party,” April 1, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-17577620

2Lall, Marie, “Viewpoint: Has a year of civilian rule changed Burma?” BBC News, November 6, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-15560414

3The Telegraph, “Burma allows access to banned news websites,” September 16, 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/burmamyanmar/8768423/Burma-allows-access-to-banned-news-websites.html

4King, Kyle, “VOA web traffic up after Burma eases censorship,” November 20, 2011, Voice of America, http://www.insidevoa.com/content/voa-website-visits-jump-after-burma-eases-censorship—134260458/178583.html

5Noreen, Naw, “News websites unblocked,” Democratic Voice of Burma, September 16, 2011, http://www.dvb.no/news/news-websites-unblocked/17696

6Radio Free Asia, “Call to end media censorship,” October 7, 2011, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/burma/censorship-10072011203136.html

7BBC News, “Burma abolishes media censorship,” August 20, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-19315806; Radio Free Asia, “Burma ends censorship,” August 20, 2012, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/burma/censorship-08202012151936.html

8Radio Free Asia, “Burma ends censorship,” August 20, 2012, http://www.rfa.org/english/news/burma/censorship-08202012151936.html

9Associated Press, “Burma leader praises opponent Suu Kyi at UN,” September 27, 2012, http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/story/2012/09/27/burma-president-congratulates-suukyi.html

10For more information on ONI’s testing methodology, see http://opennet.net/oni-faq

11OpenNet Initiative, “Internet filtering in Burma in 2005: A country study,” http://opennet.net/studies/burma

12OpenNet Initiative, “Internet Filtering in Burma (Myanmar) in 2006-2007,” http://opennet.net/studies/burma2007

13OpenNet Initiative, “Burma,” http://opennet.net/sites/opennet.net/files/ONI_Burma_2010.pdf

14OpenNet Initiative, “Burma (Myanmar),” August 2, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/burma

15Citizen Lab, “Behind Blue Coat: Investigations of commercial filtering in Syria and Burma,” November 9, 2011, https://citizenlab.ca/2011/11/behind-blue-coat/

16OpenNet Initiative, “Pulling the plug: A technical review of the Internet shutdown in Burma,” http://opennet.net/research/bulletins/013

17OpenNet Initiative, “Pulling the plug: A technical review of the Internet shutdown in Burma,” http://opennet.net/research/bulletins/013

18Villeneuve, N., & Crete-Nishihata, M. (2011). Control and resistance: Attacks on Burmese oppositional media. In R. Deibert, J. G. Palfrey, R. Rohozinski, & J. Zittrain (Eds.), Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace (pp. 153–176). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

19Mizzima, “Fresh attack on Mizzima website” August 8, 2009, http://www.mizzima.com/news/inside-burma/2599-fresh-attack-on-mizzima-website.html

20Labovitz, Craig, “Attack severs Burma Internet,” Arbor Networks Security Blog, November 3, 2010, http://ddos.arbornetworks.com/2010/11/attac-severs-myanmar-internet/

21Content categorized as “social” includes material related to sexuality, gambling, and illegal drugs and alcohol, as well as other topics that may be socially sensitive or perceived as offensive.

22Content categorized as “political” focuses primarily on Web sites that express views in opposition to those of the current government. Content more broadly related to human rights, freedom of expression, minority rights, and religious movements is also included in this category.