London Calling

Two-Factor Authentication Phishing From Iran

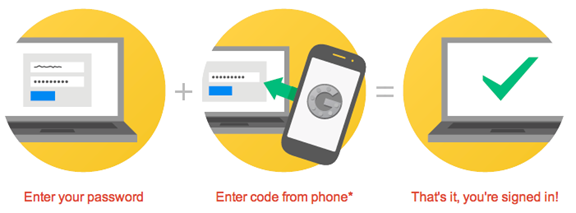

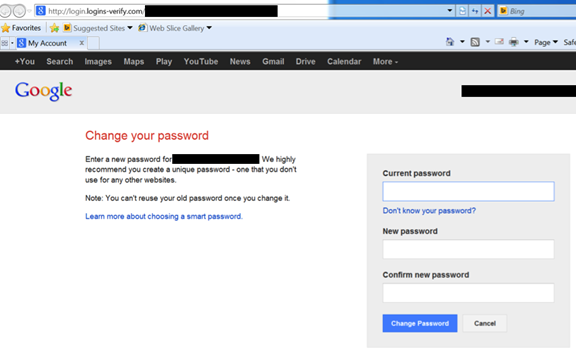

Image 1: This diagram shows basic two-factor authentication at work. Image by Google Inc.

This report describes an elaborate phishing campaign using two-factor authentication against targets in Iran’s diaspora, and at least one Western activist.

Summary

This report describes an elaborate phishing campaign against targets in Iran’s diaspora, and at least one Western activist. The ongoing attacks attempt to circumvent the extra protections conferred by two-factor authentication in Gmail, and rely heavily on phone-call based phishing and “real time” login attempts by the attackers. Most of the attacks begin with a phone call from a UK phone number, with attackers speaking in either English or Farsi.

The attacks point to extensive knowledge of the targets’ activities, and share infrastructure and tactics with campaigns previously linked to Iranian threat actors. We have documented a growing number of these attacks, and have received reports that we cannot confirm of targets and victims of highly similar attacks, including in Iran. The report includes extra detail to help potential targets recognize similar attacks. The report closes with some security suggestions, highlighting the importance of two-factor authentication.

Update: Iranian Gov-Linked Media Respond to Coverage of This Report

Iranian media outlet Masregh News, which is reportedly close to Iran’s intelligence and security services, published a response to the reporting around this post. The Masregh article specifically took issue with an IB Times report that draws a connection between Citizen Lab’s report and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. It is important to note that the Citizen Lab report does not make this attribution.

The Mashregh News report dismisses the connection made in the IB Times, and calls the link between this attack and previous phishing around the 2013 election “irrelevant.” The article also intimates that because Iranian media have previously reported on phishing attacks, the Iranian Government is not responsible.

Part 1: Background

What is Two-Factor Authentication?

Two-factor authentication (2FA) is an authentication tool used by many services to increase account security against password theft and phishing. The most commonly used form of 2FA is to send users a text message with a code once they have entered their password. The text message goes to a previously registered phone. When enabled, 2FA frustrates attackers who have simply stolen users passwords.

Implementing 2FA raises the bar on phishing attempts: In order to work, the attacker must gain access to both the victim’s password, and the single-use code. Typically codes expire quickly, presenting an additional hurdle to an attacker.

Attacks on 2FA: Nothing New Under the Sun

As researchers have observed for at least a decade, a range of attacks are available against 2FA. Bruce Schneier anticipated in 2005, for example, that attackers would develop real time attacks using both man-in-the-middle attacks, and attacks against devices. The“real time” phishing against 2FA that Schneier anticipated were reported at least 9 years ago.

Today, researchers regularly point out the rise of “real-time” 2FA phishing, much of it in the context of online fraud. A 2013 academic article provides a systematic overview of several of these vectors. These attacks can take the form of theft of 2FA credentials from devices (e.g. “Man in the Browser” attacks), or by using 2FA login pages. Some of the malware-based campaigns that target 2FA have been tracked for several years, are highly involved, and involve convincing targets to install separate Android apps to capture one-time passwords. Another category of these attacks works by exploiting phone number changes, SIM card registrations, and badly protected voicemail.

Iranian Phishing

Many previous phishing campaigns have been described and linked to Iranian attackers. For example, attacks against Gmail accounts have been regularly noted, including a report on the Google Security Blog (also available in Farsi here) describing a campaign that escalated before elections in 2013. At the time, Google also linked this attack to a previous attempt to use fake SSL certificates for targeted attacks against Gmail accounts within Iran. In many other cases, Iranian attackers have coupled phishing with other forms of malware attack (see below: Not Their First Time: Links With Other Campaigns).

While attacks against 2FA are widely documented in the context of online fraud, the rise in use of 2FA by users of free online services may be leading other categories of attackers, such as political attackers, to begin developing their own versions of these attacks.

Part 2: Three “Real Time” Attacks

Attack 1: “The Iran” is logging in to your account!

How Does This Attack Work?

This “real time” attack attempts to phish both the user password and the 2FA one-time code. The attacker does this by showing fraudulent pages that simulate the Gmail 2-step login process to the victim. The attacker collects the victim’s input, while simultaneously logging in to the real Gmail page. The attacker’s login attempt triggers Google to send a genuine 2FA code to the victim, which the attacker then collects and enters themselves. We have seen several versions of the attack, including one not accompanied by SMSes.

Attack Narrative

This section gives a narrative of how one version of this attack unfolded. (Personally identifiable information has been redacted to protect the target’s identity.)

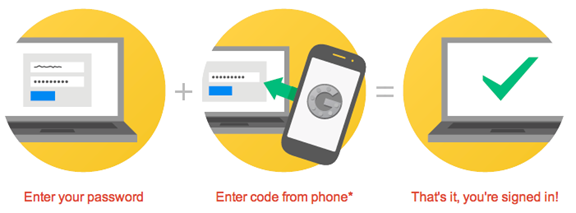

Step 1: SMS from “Google” to create fear of an account compromise

The attack began with an early morning SMS message sent to the target. The message copied the style of Google SMS alerts and “notified” the target that there was an unexpected sign-in attempt. The sending number was unknown to the target.

We believe this message was an attempt to create a pressing concern on the part of the target that a personal account had been compromised.

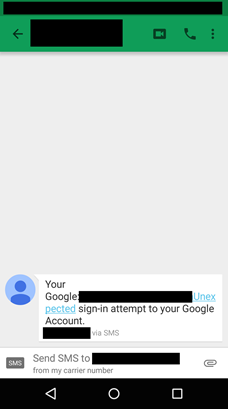

Step 2: Immediate follow up with “Sign-in attempt” notification

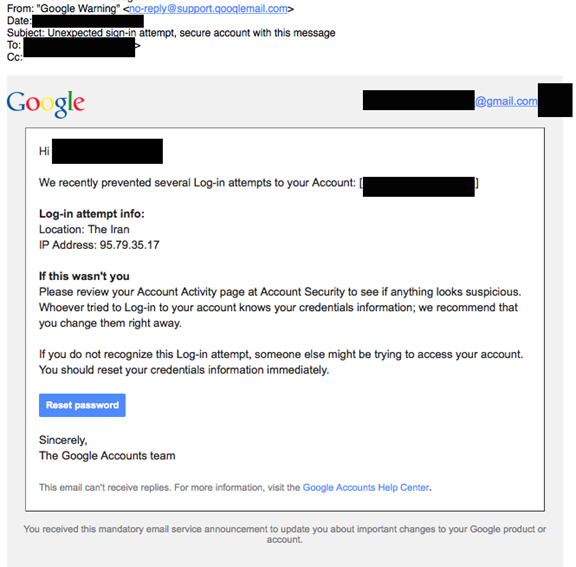

Less than 10 minutes after receiving the first SMS, the target received an e-mail masquerading as a Gmail Log-in attempt notification. Importantly, the e-mail was carefully populated with personalized details of the target including the target’s name, e-mail, and profile picture.

Notably the fake “Unexpected sign-in attempt” notification states that the attempt is from “The Iran.” For a target concerned about being hacked by groups in Iran, this could easily create a sense of concern.

The displayed message sender is also an attempt to create a lookalike for a Gmail domain.

We found that domain was used in at least one other attack of this type.

Step 3: Trick target into entering password and wait for the 2FA code

Clicking on the “Reset Password” link yields a carefully crafted phishing page. We have partially redacted the page URL to protect the privacy of the target.

http://login.logins-verify[dot]com/[redacted]

The page is personalized for the target, and includes the target’s e-mail address and name. It includes additional code, borrowed from Google, to create the appearance that the target is viewing a genuine Google page.

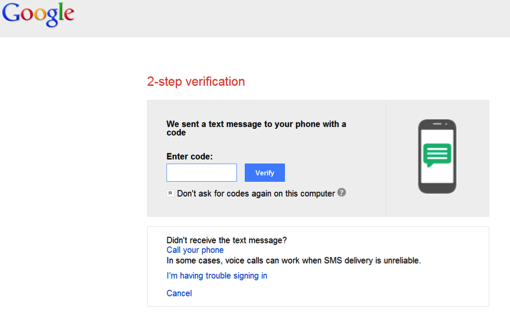

Entering information in this page and clicking on “Change Password” leads to a second page that appears to be a 2FA code request.

For this attack to work, the attackers must actively monitor the phishing page. Once the target enters their password into the phishing site the attackers likely use the credential to attempt to log in to gmail. The attacker’s login attempt then triggers the sending of a 2FA code from real Google to the target. They then wait for the target to enter the 2FA code from Google. Once the target enters the code, the attackers are able to take control of the account and (presumably) change the credentials.

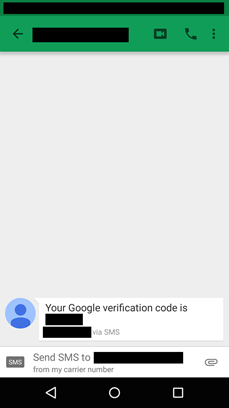

Step 4: Keep up the pressure with fake 2FA notifications

In this case, the attack failed. The target sensed something was not right and did not enter any credentials. Over the next hour, perhaps growing frustrated, the attackers sent the target a stream of fake SMS messages. These messages purported to be a Google 2FA verification code. The target received more than 10 messages in short succession. Most messages came from different numbers, all unknown to the target.

We suspect that these messages were an attempt to put psychological pressure on the target, and enhance the fiction that an attacker already had the target’s password. The attackers must have hoped that enough messages would trigger action. The final ruse failed, and the attack was unsuccessful.

Attack 2: Relax, I Already Know A Lot About You

How Does This Attack Work?

This second attack, which we tie to the same actors, has similar characteristics. In this case, the bait is slightly different, involving a phone call and a proposal. The ultimate goal, again, is to convince the target to enter both their password and 2FA code.

Attack Narrative

Step 1: Call up target with a ‘proposal’

The attack began with a morning call from a number in the UK. A male voice spoke in Farsi under the pretext of offering a potential collaboration. The attacker mentioned that it was related to activities in which the target was involved, both on and offline. The caller, presumably one of the attackers (or a confederate), demonstrated extensive knowledge of the target’s personal hobbies and professional activities.

After making several comments, which served to alarm rather than reassure the target, the unknown caller proposed a business project related to the target’s activities. The call ended with the caller promising to send the target a proposal.

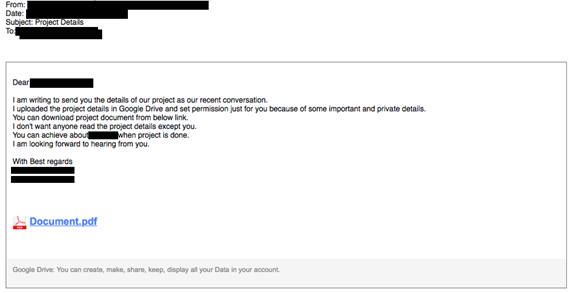

Step 2: Immediate follow up with a ‘proposal’ and a fake Google Drive link

Shortly after the phone call, the target received an email on a personal account that was not publicly used. The e-mail continued the deception, and used the same name as the caller.

The e-mail is written in a way that roughly mimics a Google Drive shared file notification. The body text proposes a project sweetened by the promise of tens of thousands of dollars.

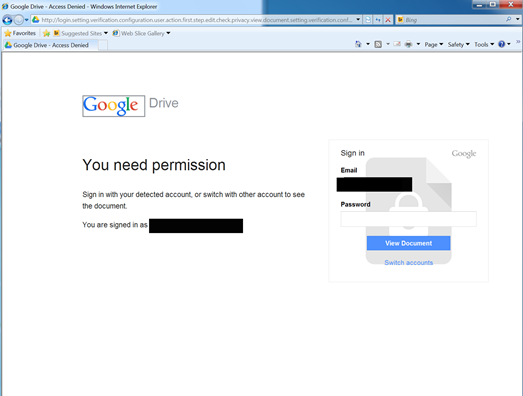

Step 3: Trick target into entering password and wait for the 2FA code

Clicking on the “Document.pdf” link leads to a fake login page for Google Drive. Again, the login is pre-populated with the e-mail and name of the target, indicating a high degree of customization.

The domain of the page (logins-verify.com) is clearly an attempt at looking official, as is the excessive subdomain (again redacted to protect the identity of the target).

http://login.setting.verification.configuration.user.action.first.step.edit.check.privacy.view.document.setting.verification.configuration.user.login.logins-verify[dot]com/[redacted]

Entering text into the login page and clicking on “View Document” yields a fake 2FA authentication page.

Attack 3: Just Open the File, I’m a Journalist!

How Does This Attack Work?

This attack is similar to Attack 2, although in these cases the attack masquerades as a request from a member of the media. The calls also come from UK numbers, one of which was shared across multiple attacks. One such attack targeted Jillian York, Director for International Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. She has agreed to allow us to name her and share additional details on the attack that targeted her. York is the only non-Iranian target we are aware of, and may have been included because her work includes extensive professional contact with Iranian advocacy groups.

Attack Narrative

Step 1: Early morning phone call

Jillian York of the Electronic Frontier Foundation was woken early in the morning by a phone call from a number in the UK.1 A male voice identified himself as a journalist with Reuters and began with small talk that indicated some knowledge of her activities. The connection was not good and the caller immediately rang back. He said there was something he wished to discuss and verified that he had the correct e-mail address for York.

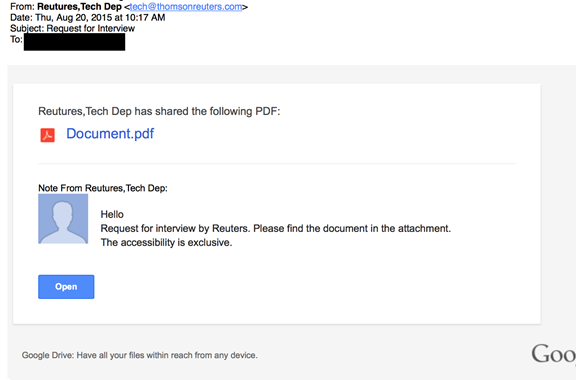

Step 2: Send the bait

Immediately after the phone calls, York received an e-mail masquerading as sent from the Reuters news agency’s “Tech Dep” and promising an interview. The spoofed e-mail contains some errors, including the misspelling of “Reutures.” The e-mail is slightly more sophisticated than those seen in earlier Google Docs style phishing from the same group

As with the other attacks the e-mail masquerades as a Google Docs e-mail share but is, in fact, a link to a phishing site, lightly disguised with a Google redirect.

https://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Freuters.users.check.login.newsia[dot]my%2FDr-Check%2FAutoSecond%3FChk%3Dj5645hgfgh5gff&sa=D&sntz=1&usg=AFQjCNF7FFFdEDdao4J8bYqow6uTZDx18w

Interestingly, the text “Reutures, Tech Dep has shared the following PDF” contains a link to the following Gmail address. The same address is present in the “reply to” of the message.

mailto: [email protected]

Other attempts also contain e-mail addresses in the e-mail body, but we are not including them to preserve the anonymity of other targets.

Step 3: Keep up the pressure

The target did not immediately click the link, and the attacker, probably anxious for his effort to pay off, called back. York prudently said that if he wished to send a message it should be included in the message body.

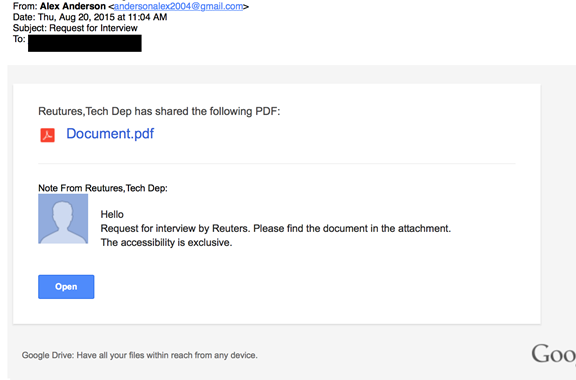

Step 4: If at first you don’t succeed

The attacker then sent a second message, this time using another name. The message contained another fake Google Doc link. This time the attacker used a different e-mail address with a western sounding name “Alex Anderson.” The phishing link is the same as the earlier message.

The attacker followed up with another call, further attempting to persuade York to open up the document. The efforts failed, with the attacker’s tone becoming increasingly “belligerent.”

“This is from my personal address! Just open it!”- The increasingly frustrated attacker on the phone

In total, the attacker called York more than 30 times over the next day. The attack had failed.

Step 5: Other avenues

While this attack was ongoing, York’s Facebook account was targeted with password reset attempts. As the attacker did not control her recovery e-mail accounts, the attempts failed.

Part 4: The Attacker? Many Clues

The attacks we have reported here stand out by virtue of both the extensive effort expended by the attackers, and their seemingly detailed knowledge of the public and private activities of their targets. We have observed this campaign over several months, and note that it has undergone slight evolution.

Phishing Infrastructure

The attacks share a wide range of features, and in some cases the same domain. A key feature of the domain registrations is impersonating the WHOIS for Google. For example, Attacks 1 and 2 both use the domain “logins-verify[dot]com”

Whois for logins-verify[dot]com

Date Checked

2015-06-28

Registrant

Google Inc.

Registrar

Onlinenic Inc

Created

2015-06-27T04:00:00+00:00

Updated

2015-06-27T03:27:15+00:00

Expires

2016-06-27T04:00:00+00:00

Name Servers

ns1.dns-diy.net, ns2.dns-diy.net

Email

[email protected] (a,t,r)

Name

MarkMonitor, Inc. (a,t,r)

Organization

Google Inc. (a,t,r)

Street

1600 Amphitheatre Parkway (a,t,r)

City

Mountain View (a,t,r)

State

CA (a,t,r)

Postal

94043 (a,t,r)

Country

US (a,t,r)

Phone

16502530000 (a,t,r)

Fax

16506188571 (a,t,r)

Notably, however, the WHOIS record contains an interesting typo:

We found that this misspelled e-mail was also used to register a range of other domains with an apparent phishing focus:

| Domain | IP | IP Organization | Org Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| service-logins[.]com | 162.222.194.51 | GLOBAL LAYER BV | US |

| logins-verify[.]com | 162.222.194.51 | GLOBAL LAYER BV | US |

| signin-verify[.]com | 141.105.65.57 | Mir Telematiki Ltd | RU |

| login-users[.]com | 31.192.105.10 | Dedicated servers Hostkey.com | RU |

| account-user[.]com | 141.105.66.60 | Mir Telematiki Ltd | RU |

| signin-users[.]com | 162.222.194.51 | GLOBAL LAYER BV | US |

| signs-service[.]com | 141.105.68.8 | hostkey network | RU |

Meanwhile, other attacks similar to Attack 1 (but not described in detail above) use a similar-looking domain to host an identical phishing page.

services-mails[dot]com

Many of the attacks disguise the phishing page URL by using a redirect through Google.

https://www.google.com/url?q=http%3A%2F%2Fservices-mails.com%2F[REDACTED]

The WHOIS for this domain also contains a fake Google registration, although it lacks the misspelling found in the other domains. Currently, the domain resolves to the following:

| Domain | IP | IP Organization | Org Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| services-mails[.]com | 134.19.181.85 | GLOBAL LAYER BV | NL |

Finally, the phishing site described in Attack 3 appears, unlike the others, to be a compromised domain belonging to a Malaysian company that provides bus services in Southeast Asia.

reuters.users.check.login.newsia.my

E-mails

Many, but not all of the attacks, spoofed the domains of legitimate sites. The attackers appear to be using a php mail script loaded onto compromised websites. For example, many attacks used the website of a Texas lawyer specializing in injuries during birth. We contacted the firm, and they deleted the malicious scripts and updated their site.

In other cases, the attackers seemed to have used lookalike domains in the reply-to, like:

qooqlemail.com

Although we were not able to confirm whether the attackers control this domain, the WHOIS for this domain may represent an interesting avenue for future research:

Registrant Name: Ali Mamedov

Registrant Organization: Private person

Registrant Street: versan 9, 16/7

Registrant City: Kemerovo

Registrant State/Province: other

Registrant Postal Code: 110374

Registrant Country: RU

Registrant Phone: +7.4927722884

Registrant Email: [email protected]

The e-mail address:

Has been previously associated with another potential phishing domain:

bluehostsupport.com

Finally, several of the messages came from e-mail accounts hosted on free mail services, like Gmail. For example:

Interestingly, some of the addresses used in the phishing campaign are associated with active (although likely fraudulent) social media profiles.

Not Their First Time: Links With Other Campaigns

The misspelling in the WHOIS record also directed us towards previous reports:

| Thamar Reservoir: An Iranian cyber-attack campaign against targets in the Middle EastClearSky Sec | http://www.clearskysec.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Thamar-Reservoir-public1.pdf |

| OPERATION WOOLEN-GOLDFISH: When Kittens Go Phishing Trend Micro | http://www.trendmicro.com/cloud-content/us/pdfs/security-intelligence/white-papers/wp-operation-woolen-goldfish.pdf |

The ClearSky Sec report notes other attacks described by security companies with similarities in practices used by attackers (but not always similarities in infrastructure). These include:

| Ajax Security Team, Operation Saffron RoseFireEye | https://www.fireeye.com/resources/pdfs/fireeye-operation-saffron-rose.pdf |

| Uncovering NEWSCASTERISight Partners | http://www.isightpartners.com/2014/06/uncovering-newscaster-experts-cyber-threat-intelligence/ |

Interestingly, the shared connections, tools, techniques and practices across threat groups do not necessarily indicate collaboration, or conclusive attribution. It may be that these threat actors actively share techniques and practices that work.

This report expands on what is known about the targets of interest to this group, and further indicates an interest in Iranis in the diaspora, and particularly those who are activists.

Conclusion

Two-factor authentication won’t eliminate phishing, but this case shows how it increases the time and effort attackers must expend. In this case, attackers had to phish two pieces of information: the password and the two-factor authentication code. The deception had to last through an entire falsified login flow. This approach required a more involved deception than a simple one-off phish, which the attackers may have learned through trial and error. Moreover, they had to phish in “real time,” given the expiration time of the two-factor authentication code. The effort involved suggests that, without serious automation, this attack technique will not scale well.

The attack also revealed several telling details about these attackers that complement previous reports. First, the attackers have targets that extend beyond the groups mentioned in reports by Clearsky and Trend Micro, and into activist circles. Second, these attackers have clearly conducted some detailed research into their targets’ activities, further suggesting a highly targeted attack.

Although “real time” attacks against two-factor authentication have been described for at least a decade, there are few public reports of such attacks against political targets. It may be that, as a growing number of potential targets have begun using two-factor authentication on their e-mail accounts out of a concern for their security, politically-motivated attackers are borrowing from a playbook that financial criminals have written over the past decade.

Practical Note: Two Steps Attackers Hate!

Use Two Factor Authentication

The extra deception that the attackers were forced to use in these cases was spotted by those who shared attacks with us. By using two-factor authentication and staying vigilant, the targets stayed safer. Implementing two-factor authentication on all of your accounts is an important security step for everyone. Click here for a comprehensive list of two-factor authentication providers. Google also recommends that, for increased security, you use the Google Authenticator App over the text-message based approach. Click here for a guide to setting up the Google Authenticator App.

If you want to take the next step and prevent this whole class of phishing, consider investing in an inexpensive U2F Key to use with compatible online accounts.

One Quick Check to Spot These (More Obvious) Fakes!

When you are logging into Gmail or other mail services you should always see “https://www.accounts.google. com” or similar at the front of the webpage URL. Here is a real Gmail login (left) and a fake login page (right).2

Some fakes won’t be so sloppy. Some attackers may get a certificate for a malicious domain, and it is possible (although difficult to do and hide) to get a fraudulent certificate for a major domain. Still, looking to make sure the base domain is correct is a simple practice worth following.

Special Thanks

The anonymous targets who have generously shared these materials with us; Jillian York (EFF); Citizen Lab colleagues including Morgan Marquis-Boire, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, Bill Marczak, Ron Deibert, Irene Poetranto, Adam Senft, and Sarah McKune; Gary Belvin (Google) and Justin Kosslyn (Google Ideas); Cyber Arabs; Jordan Berry, Nart Villeneuve; and two anonymous colleagues.

Thanks also to Frederic Jacobs who suggested a change to the wording of the HTTPS check text.