NSO Group Infrastructure Linked to Targeting of Amnesty International and Saudi Dissident

Citizen Lab validates Amnesty International investigation showing targeting of staff member and Saudi activist with NSO Group’s technology.

This report is a short post co-timed with Amnesty’s report “Amnesty International Among Targets of NSO-powered Campaign”.

Key Findings

- Amnesty International reports that one of their researchers, as well as a Saudi activist based abroad, received suspicious SMS and WhatsApp messages in June 2018. Amnesty International researchers have concluded that the messages appeared to be attempts to infect these phones with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

- Amnesty International shared the suspicious messages with us and asked us to verify their findings, as we have been tracking infrastructure that appears to be related to NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware since March 2016.

- Based on our analysis of the messages sent to these individuals, we can corroborate Amnesty’s findings that the SMS messages contain domain names pointing to websites that appear to be part of NSO Group’s Pegasus infrastructure.

1. The Messages

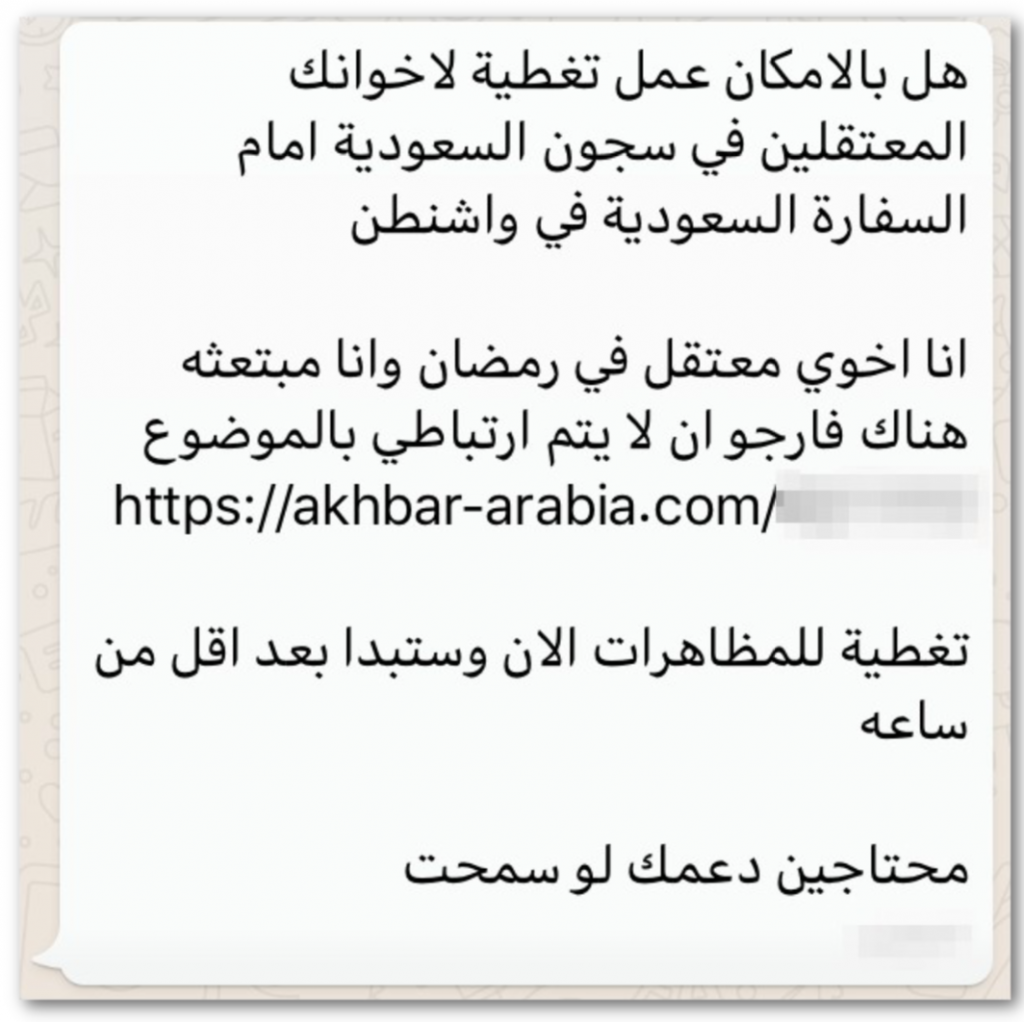

During the course of their investigation Amnesty International shared the following SMS and WhatsApp messages with us, including their links.

Suspicious WhatsApp and SMS Messages that Amnesty shared with us, along with their translations.

Links Appear to Match NSO’s Infrastructure

The domain names in the messages, social-life[.]info and akhbar-arabia[.]com, appear to be part of NSO Group’s Version 3 infrastructure (Section 2), which was put into place after our initial reporting on NSO Group in August 2016. These two domain names also appear to match a cluster of domain names in NSO Group’s Version 3 infrastructure that are associated with a Saudi Arabian focus.

If the targets had clicked the links, their phones would likely have been infected with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware. NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware allows an operator to snoop on activity in the vicinity of an infected device by turning on the device’s webcam and microphone, to record calls and log messages in mobile chat apps, and to track the device’s movements.

A Related Infection Attempt

At the beginning of June 2018, a picture of an SMS message containing a link to social-life[.]info was widely shared across the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries in WhatsApp groups and on Twitter, along with a warning that the SMS was designed to hack phones. The text message read: “You have a court case against you, #4589331 on date 5/29/2018. For more information, please visit the website: [malicious link]”.

We were unable to obtain any exploits or spyware from the link. We noticed that the link redirected to the legitimate website of Qatar’s Superior Committee of Justice: sjc.gov[.]qa (NSO operators can configure a decoy site to which exploit links should redirect after the links expire, or if spyware installation fails), and that the message was received by a subscriber to a Qatari phone company, Ooredoo, that operates in multiple GCC countries.

In addition to being widely shared, the link was submitted to urlscan.io. In the wake of this breach of NSO infrastructure secrecy, several Saudi-focused domains were shut down the week of June 4, 2018, including:

social-life[.]info

akhbar-arabia[.]com

arabnews365[.]com

kingdom-deals[.]com

2. NSO’s Infrastructure: A Tale of Three Versions

We first discovered what appeared to be NSO’s infrastructure (Version 2) while investigating a UAE-based threat actor, Stealth Falcon. We attributed the infrastructure to NSO by noticing an overlap between the Version 2 infrastructure we discovered, and an earlier version of NSO’s infrastructure that we discovered by examining historical Internet scanning data (Version 1).

| Infrastructure Version | Fingerprints | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GET / body matches:xefxbbxbf<HTML><HEAD><META HTTP-EQUIV="refresh" CONTENT="0;URL=http://www.google.com/"> <TITLE></TITLE></HEAD><BODY> </BODY></HTML> | Basis of attribution to NSO Group; matching domain names include: nsoqa[.]com qaintqa[.]com mail1.nsogroup[.]com |

| 2 | GET /redirect.aspx body matches:<html><head><meta http-equiv='refresh' content='0;url=http://www.google.com'/><meta http-equiv='refresh' content='1;url=http://www.google.com' /><title></title></head><body></body></html>GET /Support.aspx headers match:/^HTTP/1.1 302 FoundrnLocation: http://www.google.com// | Of the 237 IP addresses that matched Version 2, 19 previously matched Version 1. |

| 3 | (Fingerprints redacted) | One IP address and two domain names that matched Version 3 previously matched Version 2, with no lapse in registration. Five other domain names that match Version 3 show some relationship to Version 2. Also, the domains in the messages that Amnesty shared with us match Version 3: social-life[.]info akhbar-arabia[.]com |

Three Versions of NSO Infrastructure

After our Million Dollar Dissident report in August 2016, it appeared that NSO Group completely shut down their Version 2 infrastructure. However, we noticed that some indicators associated with the Version 2 infrastructure began to reappear, but no longer matched our Version 2 fingerprints. We developed further fingerprints (Version 3), and began scanning the Internet. Over the course of our scanning, we found several hundred servers matching Version 3.

We will describe our Version 3 fingerprinting and scanning efforts in detail in a forthcoming report.

| Version 3 IP Addresses / Domain names | Link to Version 2 |

|---|---|

| 95.183.51.199 pine-sales[.]com ecommerce-ads[.]org | Same indicators used in both Version 2 and Version 3 with no lapse in domain registration. |

| afternicweb[.]net | Domain name was used in Version 2. Domain was deleted and re-registered (but apparently never re-used) with WHOIS data matching two domains used in Version 3. |

| track-your-fedex-package[.]online adjust-local-settings[.]co remove-subscription[.]co | Domain names registered (but apparently never used) with WHOIS data matching two domains used in Version 3. The same domains (with different TLD) were used in Version 2. |

| banca-movil[.]com | Domain name used in Version 2; domain was re-registered and used in Version 3 with significant lapse in registration. |

Key overlaps between Version 3 and Version 2 infrastructure.

3. Review: How Does NSO’s Infrastructure Work?

Based on our analysis of the leaked NSO Pegasus documentation, and the Million Dollar Dissident case where UAE dissident Ahmed Mansoor was targeted with NSO Pegasus spyware, we have the following understanding of how NSO’s product works.

First, a government operator sends a target an enhanced social engineering message (ESEM) containing an exploit link that points to a domain name associated with the operator’s Pegasus infrastructure. Each client has their own (non-overlapping) Pegasus infrastructure, which may contain multiple domain names. Some of these domain names point to Pegasus Installation Servers, and may appear in ESEMs. Some domains point to Pegasus Data Servers, and are used solely for command and control (C&C). Domains in a client’s Pegasus infrastructure may be registered by NSO Group itself, or by the particular system’s operators.

When the target clicks on the exploit link, their device contacts the domain name, which routes their request through a chain of proxy servers (hosted on cloud VPS providers) called a Pegasus Anonymizing Transmission Network (PATN), to a Pegasus Installation Server on the operator’s premises. The PATN is designed to disguise the operator’s identity by forwarding the request through multiple intermediary servers before reaching the client’s premises. The Pegasus Installation Server examines various characteristics of the request, including the target’s device’s User-Agent header, to determine if the target’s device is supported for infection. If the device is supported, the Pegasus Installation Server returns the appropriate exploit to the target device, through the anonymizers, and attempts an infection. If infection fails for any reason, the target’s web browser will redirect to a legitimate decoy website specified by the Pegasus operator, in order to avoid arousing the target’s suspicion.

If the target’s device is successfully infected, the Pegasus implant on the device transmits collected information back to a domain name used for C&C, which is different than the domain used for infection.

4. A Growing List of NSO Abuses

Since our first publication in 2016, a steady stream of reports has revealed the abusive misuse of NSO Group’s spyware. This latest report adds additional cases to the growing list. At the time of writing, various reports indicate that up to 175 individuals may have been inappropriately targeted with NSO Group’s spyware in violation of their internationally-recognized human rights. This section provides a brief overview of these cases.

| Country Nexus | Reported cases of individuals targeted | Year(s) in which spyware infection was attempted |

|---|---|---|

| Panama | Up to 150 (Source: Univision)1 | 2012-2014 |

| UAE | 1 (Source: Citizen Lab) | 2016 |

| Mexico | 22 (Source: Citizen Lab) | 2016 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2 (Source: Amnesty, Citizen Lab) | 2018 |

Reported cases of individuals targeted with NSO Group’s Spyware

The United Arab Emirates

In 2016 award-winning human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor was targeted with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware in an operation that we linked to the UAE Government. Mansoor is currently in prison, serving a 10-year sentence for writing social media posts addressing the UAE government’s human rights record. Mansoor was previously targeted with government-exclusive spyware made by Hacking Team and FinFisher.

Mexico

In 2017 we reported that 22 members of Mexican civil society were targeted with links to NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware. The targets included lawyers, journalists, human rights defenders, politicians, anti-corruption advocates, investigators of a mass disappearance, a government scientist, and a minor child based in the United States. The case is the subject of an ongoing criminal investigation in Mexico.

Panama

Panama’s former president Ricardo Martinelli was recently extradited to Panama by the United States on charges related to “illegal wiretapping and embezzlement.” The complaint against him alleged that “Martinelli Berrocal used Pegasus for wiretapping and surveillance of his ‘targets.’” A report from Univision describes Martinelli’s use of NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware to monitor the devices of more than 150 targets, including political opponents, business rivals, members of civil society, journalists, United States citizens and embassy personnel, and even his mistress. The surveillance allegedly took place between 2012 and 2014, when his presidential term concluded.

5. Conclusion

We have been tracking what appears to be NSO Group’s Pegasus infrastructure since March 2016. We first described our fingerprinting and scanning efforts in our Million Dollar Dissident report, after which NSO Group appeared to completely shut down its infrastructure. However, it appears that when NSO Group began deploying the new version of its infrastructure, they inadvertently reused several domain names and IP addresses. This reuse facilitated our continued visibility into the infrastructure.

Amnesty International shared with us two text messages received by an Amnesty International researcher and a Saudi activist based abroad, which contained suspicious links. The links in the Amnesty messages match websites that appear to be part of NSO Group’s new infrastructure, and appear to be part of a group of NSO Group infrastructure websites that have a Saudi Arabian focus. The messages appear to represent attempts to infect the Amnesty researcher and the Saudi activist based abroad with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

No End in Sight

With up to 175 reported instances of abusive surveillance, it seems clear that NSO Group is unable or unwilling to prevent its customers from misusing its powerful spyware tools. If the Panama case is any guide, there may be a substantial number of cases of abusive surveillance beyond what Citizen Lab and our research partners have discovered.

Along with our research partners, the Citizen Lab will continue to track the proliferation and abuse of NSO Group’s spyware and that of other companies. We anticipate releasing further investigative results in a forthcoming report.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Claudio Guarnieri at Amnesty International.

Bill Marczak’s work on this project was supported by the Center for Long Term Cybersecurity (CLTC) at UC Berkeley. This work was also supported by grants to the Citizen Lab from the Ford Foundation, the John T. and Catherine D. MacArthur Foundation, the Oak Foundation, the Open Society Foundations, and the Sigrid Rausing Trust.

Editing and other assistance provided by Lex Gill and Sarah McKune.

- The complaint filed in the matter of Martinelli’s extradition from the United States alleges that Martinelli “misappropriated government resources to illegally intercept and record the private communications of at least 150 individuals whom he identified as ‘targets”’ (para. 6). It also asserts that Martinelli used Pegasus equipment for wiretapping and surveillance of his targets. It is unclear, however, if Martinelli is alleged to have used Pegasus to target each of the 150 targets, or a subset of those targets. ↩︎