We Chat, They Watch

How International Users Unwittingly Build up WeChat’s Chinese Censorship Apparatus

WeChat communications conducted entirely among non-China-registered accounts are subject to pervasive content surveillance that was previously thought to be exclusively reserved for China-registered accounts.

Key Findings

- We present results from technical experiments which reveal that WeChat communications conducted entirely among non-China-registered accounts are subject to pervasive content surveillance that was previously thought to be exclusively reserved for China-registered accounts.

- Documents and images transmitted entirely among non-China-registered accounts undergo content surveillance wherein these files are analyzed for content that is politically sensitive in China.

- Upon analysis, files deemed politically sensitive are used to invisibly train and build up WeChat’s Chinese political censorship system.

- From public information, it is unclear how Tencent uses non-Chinese-registered users’ data to enable content blocking or which policy rationale permits the sharing of data used for blocking between international and China regions of WeChat.

- Tencent’s responses to data access requests failed to clarify how data from international users is used to enable political censorship of the platform in China.

Introduction

A significant body of research over the past decade has shown how online platforms in China are routinely censored to comply with government regulations. As Chinese companies grow into markets beyond China, their activities are also coming under scrutiny. For example, TikTok, a video-based social media company, has been accused of censoring content on its platform that would be sensitive in China1. Grindr, a Chinese-owned online dating platform for gay, bi, trans, and queer people, fell under suspicion that it could be used to monitor, track, or otherwise endanger American users2.

WeChat is the most popular social media platform in China and third in the world3. While the platform dominates the market in China, it also has made efforts to internationalize and attract users globally. Like any other Internet platform operating in China, WeChat is expected to follow rules and regulations from Chinese authorities around prohibited content. Previous Citizen Lab research shows the balancing act WeChat must maintain as it attempts to keep within government red lines in China and attract users internationally. WeChat implements censorship for users with accounts registered to mainland China phone numbers. This censorship is done without notification to users and is dynamically updated, often in response to current events.4

In previous work, there was no evidence that these censorship features affected users with accounts that are not registered to China-based phone numbers. These users could send and receive messages that users with China-registered accounts could not. In this report, we show that documents and images shared among non-China-registered accounts are subject to content surveillance and are used to build up the database WeChat uses to censor China-registered accounts.5 By engaging in analysis of WeChat privacy agreements and policy documents, we find that the company provides no clear reference or explanation of the content surveillance features and therefore absent performing their own technical experiments, users cannot determine if, and why, content surveillance was being applied. Consequently, non-China-based users who send sensitive content over WeChat may be unwittingly contributing to political censorship in China.

The report proceeds as follows:

- Part 1: Background

Provides background on WeChat and an overview of previous research on surveillance and censorship on the platform. - Part 2: Technical Assessment

Presents our technical experiments, including the side-channel methods which were used to uncover the surveillance to which non-China-registered accounts are subjected, as well as the findings and discussion emergent from the analysis. - Part 3: Policy Assessment

Presents results from policy analysis, which involved interrogating Tencent’s public-facing policy documents and directly contacting the company about how it treated international users’ communications content. - Part 4: Data Access Request Assessment

Recounts what we did, and did not, learn from issuing a data access request for our WeChat data, and shows that this method failed to reveal content surveillance on the platform. - Part 5: Conclusion

Provides a brief conclusion, discusses the broad significance of our findings, and provides avenues for future research.

Part 1 – Background

WeChat (Weixin 微信 in Chinese) is one of the most popular social media apps in China, with 1.15 billion monthly active users in China and overseas as of late 2019.6 The application is owned and operated by Tencent, one of China’s largest technology companies, and was launched in 2011 as a mobile instant messaging app. Since then, Tencent’s WeChat/Weixin Group7 has developed a variety of communication functionalities in WeChat including instant messaging (e.g., one-to-one private chat, group chat), WeChat Moments (i.e., a functionality that resembles Facebook’s Timeline where users can share text-based updates, upload images, and share short videos or articles with their friends), and the Public Account platform (i.e., a blogging-like platform that allows individual writers as well as businesses to write for general audiences). Forty-five billion messages are reportedly sent using WeChat on a daily basis.8

The Chinese market presents unique challenges for Internet platform providers due to laws and regulations that hold companies accountable for the content published or transmitted on their platforms. Companies are expected to invest in human resources and technologies to moderate content and comply with government regulations on content controls. Companies which do not undertake such moderation and compliance activities can be fined or have their business licenses revoked. Meanwhile, China’s laws and regulations on content controls are broadly defined, with prohibited topics ranging from “disrupting social order and stability” or “damaging state honor and interests,” to crossing “the bottom line of socialism.”9 Previous research has shown that these vaguely defined guidelines often lead companies and individuals alike to engage in self-censorship.10

Previous work shows that WeChat conducts pervasive political censorship for users whose accounts operate under WeChat China’s terms of service; we refer to these accounts, generally, as China-registered accounts.11 Accounts which were originally registered to mainland China phone numbers fall under these terms of service, and they remain under them even if the user later links their account to a non-Chinese phone number. Files and communications which are sent to, or from, China-registered accounts are assessed for political sensitivity among other content categories. If the content of the communications is found to be sensitive, it is censored for all China-registered accounts on the platform.

Previous work has found that WeChat placed images which are sent by China-registered accounts under two different kinds of surveillance.14 Due to the computationally expensive and time-consuming methods required to analyze an image for sensitivity, these methods are not easily adapted to run in real-time. As a result, WeChat first subjects these images to file hash surveillance to assess whether the image has previously been categorized as sensitive, which is determined by checking to see if the file’s hash is present in a hash index of known sensitive file hashes. This hash index check is performed in real time. If the image’s file hash is in the hash index, it is censored in real time. Images that are not in the hash index of known sensitive files undergo content surveillance. Such surveillance involves the image being analyzed for whether it is visually similar to that of any blacklisted image. Further, text that is in the image is extracted and analyzed to determine if any of the text is blacklisted. If the image is found to be sensitive, then its file hash is added to the hash index to enable future real-time censorship. Of note, previous testing found that content surveillance was never performed in real time and that the first time that a sensitive image file is transmitted it was not censored.

In this report, we revisit how WeChat implements image surveillance. For the first time, we examine how WeChat conducts surveillance and censorship of documents sent over the platform. Moreover, we examine whether images and documents communicated entirely among non-China-registered accounts are subject to the same surveillance practices which were previously found to apply to communication to, or from, China-registered accounts.

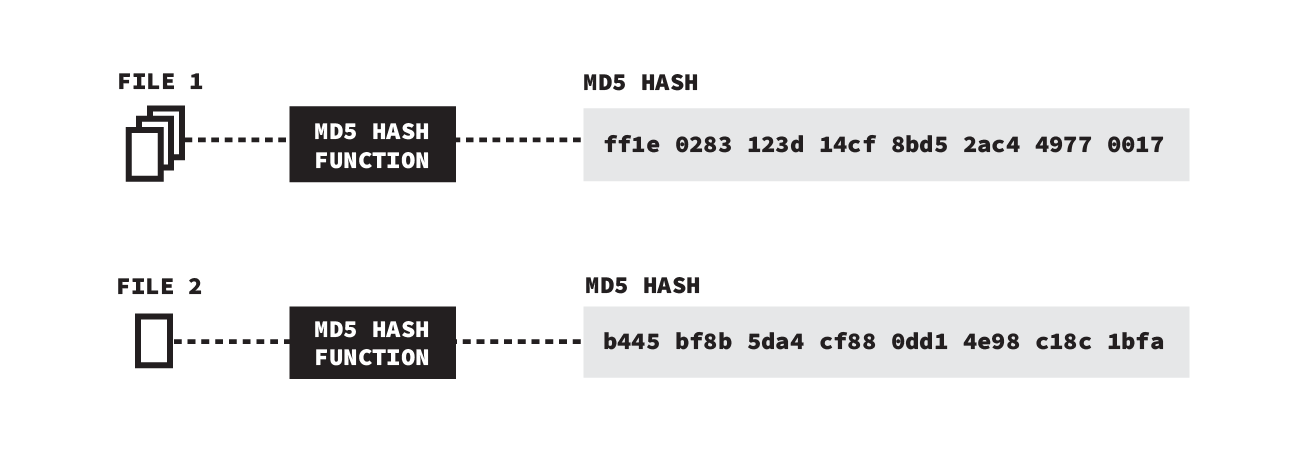

What is an MD5 hash? Hash functions are designed to map a data input, such as a message or a file, into a short, fixed-size output called a hash. The MD5 hash function is a cryptographic hash function, which is a hash function with special cryptographic properties. Cryptographic hash functions have many additional properties over ordinary hash functions, but one such property is that it should be infeasible to find two different inputs such that the hash function maps them to the same output. That is, it should be infeasible to find two different inputs with the same hash. MD5 is an older cryptographic hash function designed in 1991.

The diagram below illustrates the process of mapping a file (e.g., a document or an image) to an MD5 hash. In this example, two different images are inputted to a cryptographic hash function resulting in two unique MD5 hashes.

Part 2 – Technical Assessment

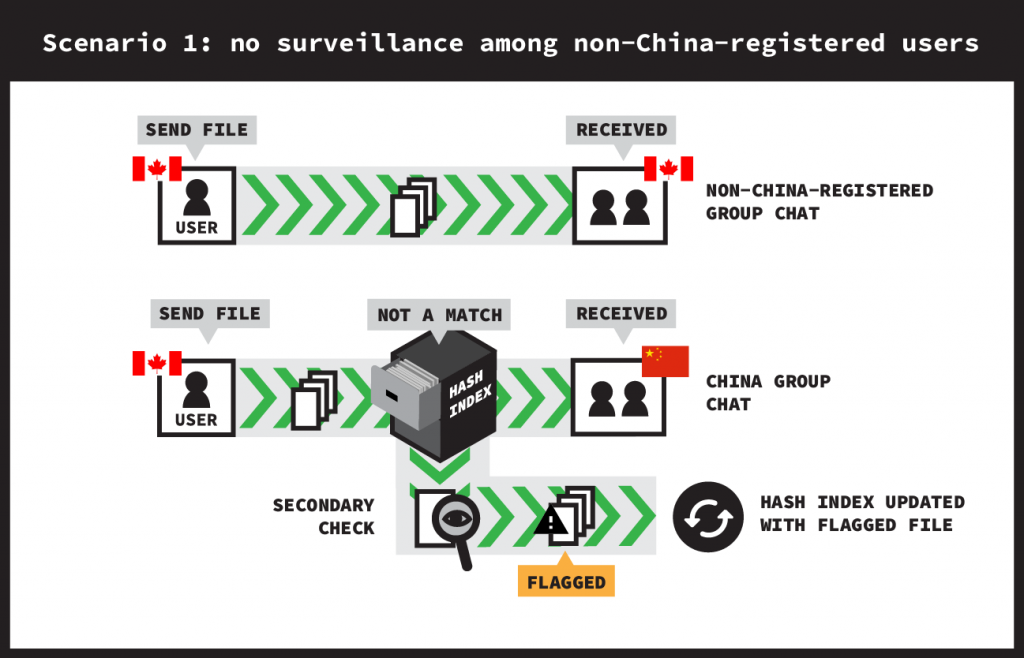

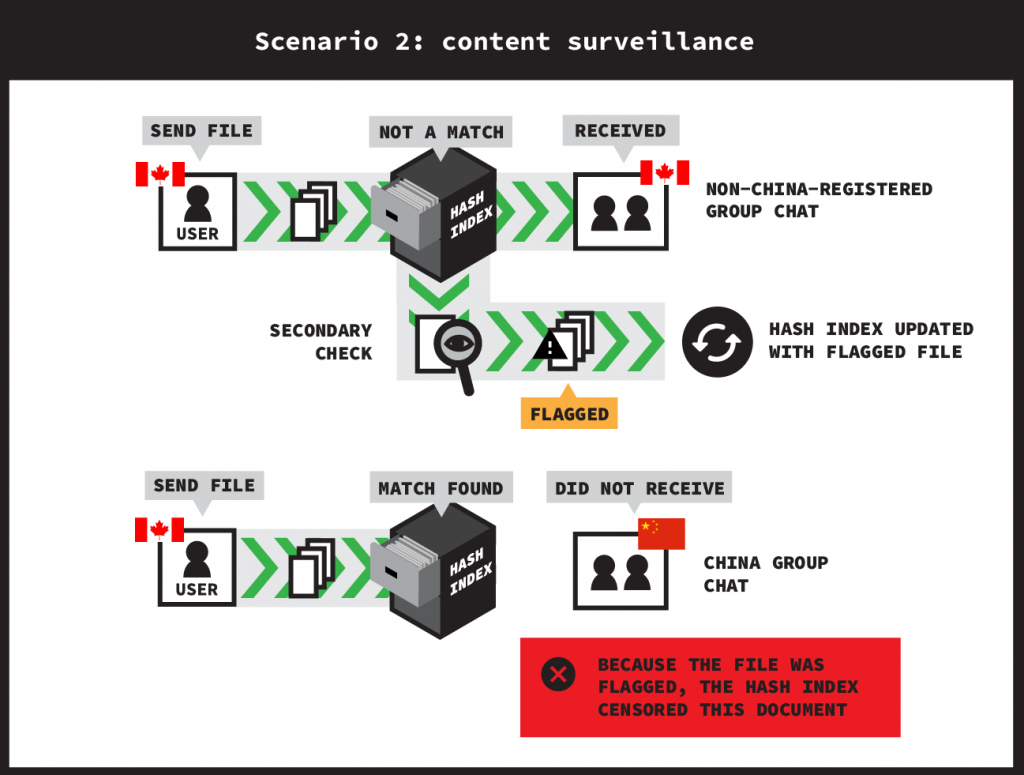

Measuring communications surveillance can be challenging due to its inherently invisible nature. In the absence of censorship, which restricts communication in a way that has a measurable effect (e.g., a message fails to be delivered), surveillance can be difficult to detect. To detect the communications surveillance of non-China-registered accounts, we developed and ran two side-channel experiments. In both experiments, we employ two channels, one communicating entirely among non-China-registered accounts and a second communicating with a China-registered account. By utilizing the hash index that censors China-registered WeChat accounts as a side channel, we were able to infer that content surveillance was occurring in the first channel by measuring for censorship in the second. We develop and performed a third experiment testing whether recalling a message containing a file removes that file’s hash from the hash index.

In short, while we did not detect censorship in communications among non-China-registered accounts, we did demonstrate that such accounts are nevertheless subject to content surveillance. Such surveillance was discovered by confirming that politically sensitive content which was sent exclusively between non-China-registered accounts was identified as politically sensitive and subsequently censored when transmitted between China-registered accounts, without having previously been sent to, or between, China-registered accounts. In the remainder of this section, we explain our pre-experiment analysis, our experimental designs, and we present our experiment’s results.

2.1 Background

Before designing our side-channel experiments, we first explored whether sensitive documents sent to, or from, China-registered accounts were surveilled and censored using a hash index. By sending sensitive documents to a China-registered account, we could observe which files were censored. We found that documents such as UTF8-encoded plain text (*.txt), Microsoft Word (*.docx), and Portable Document Format (*.pdf) documents which contained certain sensitive keyword combinations such as “法輪功 [+] 法輪大法” (Falun Gong + Falun Dafa) were censored. As part of our investigation, we sent multiple documents across multiple days. Of particular note, we sent over 50 during November 25–26, which was immediately before our experiment, as well as over 50 during December 3–5, which was during our experiment. We found that all sent documents were subject to surveillance and censored in the same way as images had been found to be surveilled and censored in previous work.15 Namely, we confirmed that documents underwent file hash surveillance and that such files were not censored in real time until they had undergone non-real time content surveillance and their file hash had been added to the hash index.

We also sought to confirm whether images were still subject to surveillance and censored as described in previous work16. We found that, unlike in previous work where content surveillance of images was not performed in real time, images were now sometimes censored in real time even if they had never been sent over the platform before. Because of this new capability of WeChat’s censorship implementation, we designed our experiment to send a large number of images such that we expected, with high probability, that at least one would not be censored in real time.

2.2 Statistical Experiment

In this section, we present our first side-channel experiment which tests for content surveillance of sensitive documents and images transmitted over WeChat. We call this experiment the statistical experiment because of this experiment’s use of statistical analysis.

2.2.1 Methodology

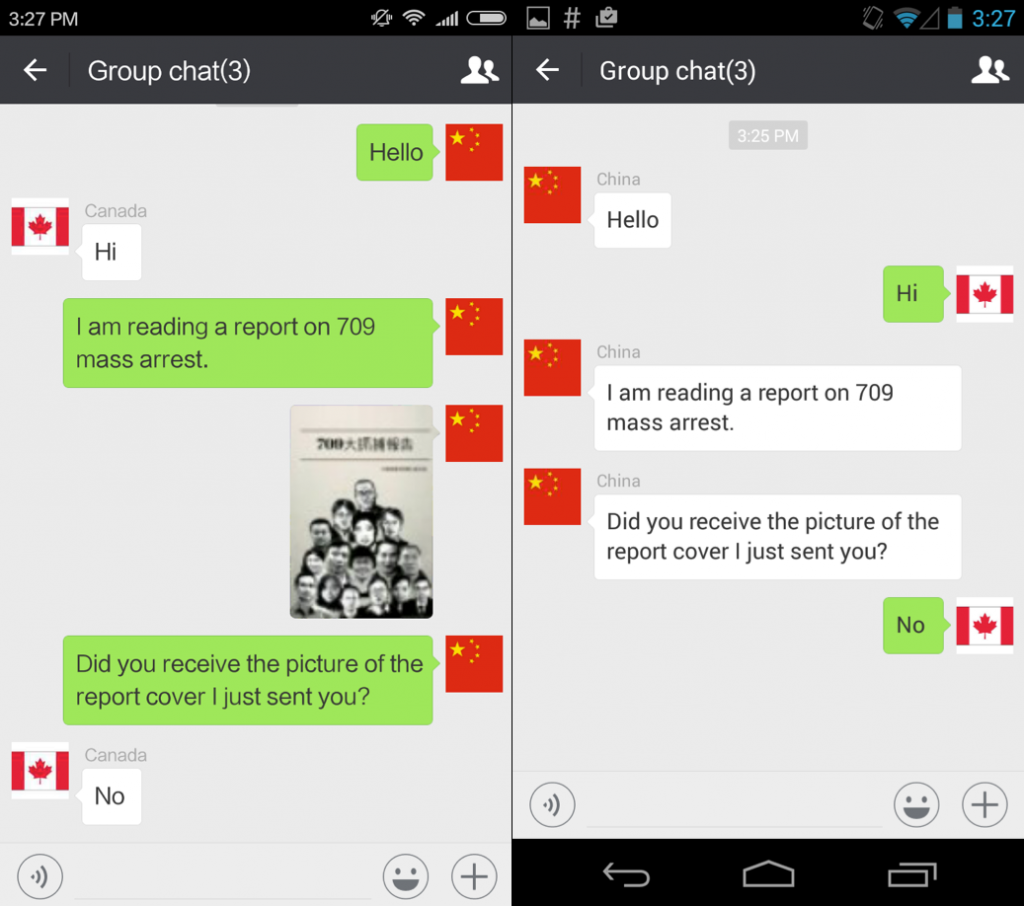

In this experiment, we use two WeChat group chat conversations to serve as our two communication channels:

- Non-China group chat. This group chat contains three non-China-registered WeChat accounts which were registered to Canadian phone numbers. In this group chat, a non-China-registered account sends content entirely among other non-China-registered accounts.

- China group chat. This group chat contains two non-China-registered WeChat accounts which were registered to Canadian phone numbers and one WeChat account that was registered to a mainland China phone number. In this group chat, a non-China-registered account simultaneously sends content to both a non-China-registered and a China-registered account. In this group chat, we are interested in whether the China-registered account receives the content or if the content is instead censored.

Our experiments rely on testing for the presence of a file’s hash in WeChat’s censorship hash index. By sending a file in the China group chat and measuring whether that file is censored in real time, we can test whether its hash is already in the hash index. However, as a consequence of this test, we introduce the hash into the hash index if it was not already present. Thus, it is important that, whenever we perform a new test, we send a unique file with a hash that has never been sent over WeChat before. We call such a file a novel file, since its hash is novel to the WeChat platform.

In the remainder of this section, we explain the design of our side-channel experiment to test for content surveillance of document and image files when sent entirely among non-China-registered accounts.

We performed the following test to evaluate whether document content surveillance takes place among non-China-registered accounts:

- Document side-channel test. We first send a novel, sensitive document in the non-China group chat and then send the same document in the China group chat. If the document is censored in real time when sent to the China-registered account, then we conclude there was surveillance of the sensitive document during the communication among the non-China group chat.

In this document side-channel test, the hash index serves as a side-channel by leaking information about whether the non-China group chat is under content surveillance by measuring for censorship in the China group chat. This method is sufficient for testing for the existence of document surveillance because, at the time of testing, WeChat did not censor documents in real time. Thus, whenever we observe real-time document censorship, we can conclude that the document had previously been subject to surveillance.

In the case of image files, we observed that sometimes WeChat censors them in real time even if they have not previously undergone content surveillance on the platform. To accommodate this behaviour, we send a sufficiently large number of images such that, if images sent entirely among non-China-registered accounts undergo content surveillance, then we will still be able to distinguish the effect this surveillance has on real-time censorship even if real-time censorship sometimes happens in the absence of content surveillance. Specifically, we first conduct the following test:

- Image side-channel test. We first send n novel, sensitive images in the non-China group chat and then send the same images in the China group chat one minute later. We count how many images were not received by the China-registered account.

We then compare the number of censored images from the previous test to that of the following test:

- Image control test. We send n novel, sensitive images in the China group chat. We count how many were not received by the China-registered account.

The difference between these two tests is that in the image side-channel test, we first send an image among the non-China-registered accounts before sending it to a China-registered account, whereas in the image control test, we send the image to a China-registered account without sending it to non-China-registered accounts first. If there is a significantly larger number of images censored in the image side-channel test, then we can conclude that sending images among non-China-registered accounts is facilitating real-time Chinese censorship.

We use statistical hypothesis testing to determine whether there is a statistically significant increase in the number of images censored in the image side-channel test than in the image control test. Namely, we perform a chi-squared test17 under the null hypothesis that sending images from non-China-registered accounts to non-China-registered accounts does not affect the probability that they will be censored in real-time when they are later sent to a China-registered account. If, according to the chi-squared test, we may reject the null hypothesis, then we can conclude that images sent entirely among non-China-registered accounts are under content surveillance and are contributing to WeChat’s Chinese censorship system.

For each image test, we send n novel images. Our desire is to choose an n high enough that our statistical test has sufficient power to determine whether content surveillance between non-China-registered accounts exists. However, we also want n to be sufficiently low to minimize the risk of WeChat taking adverse action against our testing accounts (e.g., WeChat has been known to suspend or ban accounts in response to censorship testing18). In our experiment, we will evaluate choosing n = 60.

For both document and image testing, each test requires that we send novel, sensitive documents or images that have not previously been sent over the platform to ensure that the sensitive files’ hashes are not already in the hash index. In principle, we could use entirely different sensitive documents and images. However, this approach would limit us to only performing as many file transmissions as we have known sensitive files. Thus, to facilitate testing, we generate novel, sensitive files by performing subtle modifications to a single sensitive document and a single sensitive image; we call each of these seed files. These modifications are designed to change these files’ hashes without changing their ability to be recognized as sensitive and, thus, let us generate an indefinite number of sensitive documents and images. In the remainder of this section, we explain, for both documents and images, which seed file we use and how we generate novel copies of a seed file such that the derivative files remain sensitive.

The text of the sensitive seed document:

Lorem ipsum

法轮大法

法輪大法

法轮功

法輪功

Lorem ipsum

For documents, we use as our seed document a *.docx file which contains the characters for Falun Dafa and Falun Gong in both simplified and traditional Chinese, as well as some filler text (see Figure 5). To create a novel, still-sensitive copy of it, we then append 64 alphanumeric characters chosen uniformly at random.

For images, we use as our seed file a cartoon of Liu Xiaobo (see Figure 6) that was found to be censored on WeChat in previous work19. To create a novel, still-sensitive copy of it, we append 24 KiB of random bytes to it. Since the seed file we used was a JPEG-encoded image, all data past the JPEG end-of-file marker is ignored when rendering the image; however, the appended data still causes the file to hash to a different value.

2.2.2 Experimental Setup

We ran our experiment to test for document and image file surveillance across three separate days: November 27, December 2, and December 6, 2019. We spread the experiment across three days to ensure that the behaviour we observed was consistent across time and to reduce the risk of adverse action taken against our test accounts. All measurements were performed from a University of Toronto network in Toronto, Canada. For each test, on each day, we transmitted novel, sensitive documents or images which had never previously been communicated over the platform. In the remainder of this section, we present the results of these experiments.

2.2.3 Results

| Test | Nov. 25-26 | Nov. 27 | Dec. 2 | Dec. 3-5 | Dec. 6 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Document side-channel | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 3/3 | ||

| Document control | 0/≥50 | 0/≥50 | 0/≥100 | |||

| Image side-channel | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 60/60 | ||

| Image control | 17/20 | 14/20 | 18/20 | 49/60 |

For each test, the number of files which were censored on each date

Table 1 shows the results of our experiment testing for document and image surveillance on each of the three days it was conducted. Although our experimental design did not explicitly contain a document control test, we reference one to be consistent with our presentation of the image test results. Specifically, this test refers to our implicit results from investigating how document censorship worked on WeChat, which confirmed that WeChat lacked the capability to censor documents in real time (see Section 2.1).

Our results show that on each day of testing, if a sensitive document is first sent from a non-China-registered account to non-China-registered accounts, before sending it to a China-registered account, they are censored in real time when sent to a China-registered account. This finding shows that documents sent even entirely among non-China-registered accounts undergo content surveillance and that these documents are used to build-up the censorship system to which China-registered accounts are subjected.

Unlike with documents, we observed that WeChat can sometimes censor images in real time.20 Out of 60 images sent across three days, 49 images were censored in real time when only sending them to China-registered accounts. However, if we first sent them from a non-China-registered account to other non-China-registered accounts, then all 60 out of 60 images were censored in real-time when sent to a China-registered account. To confirm that the difference in these two results are statistically significant, we performed a chi-squared test under the null hypothesis that sending images from non-China-registered accounts to non-China-registered accounts does not affect the probability that they will be censored in real time when they are later sent to a China-registered account. We reject the null hypothesis because we found that there is only a p = 0.00078 probability of observing at least as large of a difference by chance. This result shows that, in addition to documents, images sent even entirely among non-China-registered accounts also undergo content surveillance, and that images sent among non-China-registered accounts are also used to build-up the censorship system to which China-registered accounts are subjected.

Finally, for our image testing, we evaluate our choice of sending n = 60 images across each image test. At no point during testing were any of our test accounts banned for sending this number of images. Moreover, choosing this number yielded highly significant results. These findings show that sending 60 images across three different days is powerful enough to result in statistically significant results and suggests that an even smaller value of n could be used in future experiments to further minimize risk of account closure.

2.3 Collision Experiment

In Section 2.2, we presented a side-channel experiment that confirmed that documents and images which are communicated entirely among non-China-registered accounts undergo content surveillance. Unlike documents, novel images were sometimes censored in real time when sent over WeChat for the first time. Consequently, we used statistical methods to show that such images were increasingly censored when previously exposed to surveillance. In this section, we present an alternative experiment that does not require statistical analysis and which further confirms the findings of the past experiment. The method of our follow-up experiment, the collision experiment, takes advantage of the fact that WeChat uses MD5 as its file hash algorithm and that this hash function has known vulnerabilities relating to hash collisions.

2.3.1 Methodology

Our method in the collision experiment is similar to the statistical experiment described in Section 2.2, but with one significant difference. In this experiment, we never send a sensitive image in the China group chat. Instead, we send a non-sensitive image that has been specially crafted to have the same MD5 hash as that of a novel, sensitive image. As we have demonstrated in previous work21, due to a vulnerability22 in the MD5 hash algorithm, given any two images, we can modify the images’ metadata such that they have the same MD5 hash.

|  |

|---|

The sensitive (left) and non-sensitive (right) seed images used in our experiment. Examples of MD5 hash collisions are here23 (left) and here24 (right).

Specifically, we conduct the following two tests:

- Collision side-channel test. We first generate 20 novel, sensitive images with the same MD5 hashes as 20 non-sensitive images. We send the 20 sensitive images in the non-China group chat and then send the 20 non-sensitive images in the China group chat one minute later. We count how many of the non-sensitive images were not received by the China-registered account.

We then compare the number of censored images from the image collision side-channel test to that of the following test:

- Collision control test. We first generate 20 novel, sensitive images with the same MD5 hashes as 20 non-sensitive images. We send the 20 non-sensitive images in the China group chat. We count how many were not received by the China-registered account.

Like in the image experiment performed in Section 2.2, if there is content surveillance of communications sent entirely among non-China accounts, then we would expect a larger number of images to be censored in the collision side-channel test than in the collision control test. In fact, in this experiment, since we send only non-sensitive images in the collision control test, if there is surveillance, then we expect that all non-sensitive images will be censored in the collision side-channel test and that none of the non-sensitive images will be censored in the collision control test.

2.3.2 Experimental Setup

We performed this experiment on January 30, 2020, on a University of Toronto network in Toronto, Canada. Unlike with our statistical experiment, we performed the collision experiment on a single day because this experiment does not require measuring a large number of image transmissions.

2.3.3 Results

| Test | Jan. 30, 2020 |

|---|---|

| Collision side-channel | 20/20 |

| Collision control | 0/20 |

For each test, the number of non-sensitive images which were censored.

In the collision side-channel test, all 20 of the 20 non-sensitive images were censored, whereas in the collision control test none of the 20 non-sensitive images were censored. Without the use of statistics, these results demonstrate that images are under content surveillance even when sent entirely among non-China-registered accounts, and that they are used to invisibly build up WeChat’s censorship system.25

2.4 Retention Experiment

WeChat provides a feature to recall26 a message which lets users delete a chat message that has been sent within the last two minutes to prevent users from viewing it if they have not viewed the message already. The international version of WeChat’s privacy policy contains links to support documentation27 that advises users based in the European Union to use the recall feature to remove personal information from chat messages. In this section, we design and perform an experiment to evaluate whether, after a chat message containing a file is recalled, WeChat still retains its hash in the hash index.

2.4.1 Methodology

To test whether WeChat retains a hash of a recalled file, we perform the following test:

- Hash retention test. We send a novel, sensitive document in the non-China group chat in a group chat and then immediately recall the document. One hour later, we send the same document in the China group chat. If the document is censored in real time when sent to the China-registered account, then recalling the document did not remove the hash from the file index.

For this test, we generate novel, sensitive documents as described in Section 2.2.1.

2.4.2 Experimental Setup

We performed this experiment on January 7, 2020, on a University of Toronto network in Toronto, Canada. To test if the results would be different for European Union users, we repeated this experiment on January 9, 2020, using a WeChat account registered to a Belgian phone number and using a VPN server in Belgium. On each day of testing, we ran the test five times.

2.4.3 Results

| Test | Jan. 7, 2020 | Jan. 9, 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Hash retention | 5/5 | 5/5 |

The number of recalled images which were censored on each day

For both days of testing, in all five tests, the recalled document was never received by the China-registered account. This result shows that recalling a document after it is sent does not remove that file’s MD5 hash from WeChat’s hash index, either for users outside or inside the European Union.

2.5 Summary

Our experiments reveal that content surveillance is applied to both China-registered accounts as well as to non-China-registered accounts. Content surveillance between users of non-China-registered accounts is functionally undetectable unless those users conduct their own side-channel research to detect whether the documents or images that they shared have both been hashed for censorship purposes and, also, that the hashed documents or images are actually being censored. Put another way, in cases where documents or images are hashed but the files themselves are not presently censored, it would not be possible to know which, if any, files had been analyzed and hashed for potential censorship activities using the experiments we performed.

While there is a system in place to monitor and generate hashes for the documents and images transmitted between non-China-registered accounts for content which raises social or political concerns in China, our research has not demonstrated that there is an equivalent application of a censorship system in place for the communications which take place between non-China-registered accounts. Put plainly, we have not witnessed censorship between non-China-registered accounts of materials which are censored among China-registered accounts. By conducting our side-channel experiment, we were nevertheless able to measure the existence of content surveillance for such materials transmitted among non-China-registered accounts.

Moreover, the experiments show that non-China-registered accounts cannot remove hashes of sensitive content which they have sent when communicating entirely with other international users as a side effect of recalling their content. Consequently, while it may appear to users that they can recall the content of their communications, at least some of the metadata associated with such communications—such as the hashes of sensitive files—are disassociated from the retraction system. It is unclear based on our technical findings whether such a hash register would be associated with individual accounts. Nevertheless, these hashes will be used to build-up WeChat’s censorship system.

Finally, our experiments conducted on multiple days across November 2019 – January 2020 consistently show content surveillance of documents and images sent among non-China-registered users. However, our data cannot answer for how long non-China registered users’ files have been subject to such surveillance, and we cannot distinguish between this surveillance behaviour being a recent addition versus a long-standing behaviour. Although such surveillance was consistently observed on each day of testing, we cannot speak to whether such surveillance was consistently applied across days which were not tested.

Part 3 – Policy Assessment

Before a company can make their application available on the Google Play store or Apple’s App store, they must first develop and publish a privacy policy to accompany the given application. These public-facing documents are intended to inform users about how their data will be used and protected. Quite often, privacy policies and accompanying terms of service documents will include information such as what is, and is not, considered personal information or sensitive information, as well as detailed information concerning the kinds of activities a company may take towards a user’s data.

For this report, we analyzed the international (i.e., Singapore) as well as the mainland China (i.e., Shenzhen) privacy policies and terms of service documents that were associated with WeChat. The analysis was meant to help us understand how the company asserts that it handles personal information and, through this analysis, better understand whether Tencent’s international policy documentation suggests that international users’ communication might be used to develop, enhance, or maintain the hash index which is used to censor communications between China-registered WeChat accounts. We also sent detailed questions to Tencent’s international data protection office to seek clarity concerning the company’s privacy policy and terms of service documentation. We also hoped that responses from the office would confirm the report’s technical findings and disclose the rationales for which content transmitted between non-China-registered accounts was used to develop, enhance, or maintain the censorship system which is applied to China-registered accounts.

Overall, we found, first, that neither the China nor international public policy documents made clear to users that non-China accounts could have their content surveilled and the resulting hashes used to censor content for China-registered accounts. Second, we found it was plausible that the international policy documents could permit content surveillance of international users’ communications, but the company did not respond to these questions. Third, we found that it was unclear on what basis the hashes of international users’ communications could be shared with WeChat China, and the company did not respond to these questions.

3.1 Methodology

We undertook three related activities to assess Tencent’s mainland China and international privacy policies and terms of service documents for WeChat28: downloading relevant policies (e.g., privacy policies and terms of service agreements); assessing the aforementioned policies using a pre-determined series of structured questions; and contacting the company’s international data protection office with questions about whether content transmitted between non-China-registered accounts was ever used to develop, enhance, or maintain the censorship system applied to China-registered accounts.

3.1.1 Obtaining Relevant Public-Facing Policies

Relevant policies were downloaded from Tencent’s websites in December 2019. We specifically downloaded the following policies which apply to China-registered WeChat accounts:

- Agreement on Software License and Services of Tencent Weixin (Simplified Chinese29 and English30 versions)

- Weixin Privacy Policy Protection Guidelines (Simplified Chinese31 and English32 versions)

- Standards of Weixin Account Usage (Simplified Chinese33 and English34 versions)

Each of these documents are available in several languages, including English, simplified Chinese, and traditional Chinese.

We downloaded the following policies which applied to non-China WeChat accounts:

We primarily analyzed WeChat China’s documents in English to facilitate comparing them directly with WeChat’s international policies. We did, however, also examine the simplified Chinese version of WeChat China’s documents to determine if there were significant differences between the Chinese and English; such discrepancies could potentially be notable because the Chinese version of the documents prevails over any versions of the documents in case of any inconsistency and discrepancy.38

3.1.2 Structured Question Set

We assessed the collected privacy policies, terms of service documents, and acceptable use policies using a structured question set. This question set is based on similar assessments that Citizen Lab researchers have conducted in the past of telecommunications companies, fitness tracker companies, online dating companies, and stalkerware companies.39 Assessment categories were divided into specific questions pertaining to:

- How Tencent presents and has developed its privacy policy: e.g., “Is there a link to a privacy policy on the company’s webpage?,” “Is there a reference to compliance with: national privacy laws, international guidelines, and/or self-regulatory instruments from associations?,” “Is there a statement concerning which nation/court proceedings must go through?”

- How Tencent addresses questions from its users of WeChat: e.g., “Is there a contact to a privacy officer listed?” and “Is there a description/discussion of who you can complain to if you’re unsatisfied with the information provided by the company?”

- How Tencent captures personally identifiable information (PII): e.g., “Is there specification about the kinds of PII (i.e., information about the ‘users’) collected? If so, what types of categories are listed?,” “Is there any distinction made between sensitive and non-sensitive PII?,” and “Are there specifications for where the information is stored?”

- How, or under what conditions, Tencent might disclose collected data: e.g., “Is there a specification on the kinds of organizations that users’ information may be disclosed to?,” Does the company use the term ‘sharing’ or ‘selling’ information to third parties?,” and “Does the company reserve the right to share information with other parties in the case that they suspect a law has been violated or to exercise the company’s own legal rights, or to remain compliant with the law?”

- Are there rationales under which Tencent might ‘hash’ the content of international users’ communications?

- Are there rationales under which Tencent might block or censor content?

Combined, these questions were designed to help us understand the company’s compliance with laws designed to protect persons’ privacy, whether the company has processes in place to help individuals answer questions about their privacy or business practices, the kinds of data that the company asserts it does collect and disclose to other parties, and specifically whether the policies permit or justify Tencent’s hashing of communications content transmitted between non-China-registered accounts.

3.1.3 Communication with Data Protection Office

We contacted Tencent’s international data protection office to seek further clarity concerning the privacy policy and terms of use policies which applied to international users. We adopted this methodology to better understand how the company interpreted its policies as well as to seek confirmation or denial that it hashed the content of its international users’ communications. The letter contained eight core questions; a copy of the letter is available in Appendix A.

In addition to seeking clarity concerning the company’s public policy documentation, we also sought to better understand the extent to which persons who were involved in Tencent’s international policy work understood, or were made aware of, how WeChat functionally operated. Specifically, we contacted the company after completing our experiments that showed communications between non-China registered accounts were used to develop, enhance, or maintain the hash index that is used to censor content between China-registered account users. Additionally, we wanted to understand if the international data protection officer was aware of such surveillance of international users’ communications content.

3.2 Results

The following sections present the most significant findings that emerged from our policy assessment.

3.2.1 General Policy Questions

WeChat China’s and WeChat International’s websites both provided links to their respective services’ privacy policies or terms of service on the homepage of their respective websites. Links on WeChat China’s homepage directed users to the Chinese versions of respective policies, and from there users could choose to view the policies in other languages.

WeChat China and WeChat International both included references to the national laws and regulations with which the respective entities comply. In the case of WeChat China, the policies included general references to “relevant laws and regulations” without specifying the specific ones the company complied with, with exception of policies concerning content moderation.40 In the case of disputes, users must submit them to the local people’s court41 in Nanshan District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province of the People’s Republic of China.42

In contrast, WeChat International’s policies made reference to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) (i.e., US copyright law) and broad references to European laws, though the policies did not explicitly cite the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). WeChat International’s policies asserted that the governing jurisdiction for any disputes or claims, with the exception of those that pertained to US- and EU-based users, was the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. The Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre was responsible for conducting any arbitration between users and WeChat International. However, in cases of US-based users, the governing law and dispute resolution would take place in the state or federal courts of California, with trial by jury and class action legal proceedings waived as a condition of using the service. For EU-based users, if the person was classified as a “consumer” (per EU Direction 83/2011/EU) then disputes were to be referred to, and resolved by, “the court of the person’s place or residence of domicile.”43

Both WeChat China’s and WeChat International’s privacy policies made partial references to their terms of services and other applicable documents, including the Standards of Weixin Account Usage for WeChat China users and the Acceptable Use Policy for WeChat International users. However, the entities did not always provide links to the relevant documents to which they referred. While WeChat China linked to its terms of services in its privacy policy, its privacy policy did not provide links to the terms of services. In the case of WeChat International, its terms of service included links to the privacy policy, and vice versa.

WeChat China noted when the last updated date and effective date were for its privacy policy but it did not do so for its terms of service. WeChat International provided information about when each of the respective documents was last updated. Neither of the two entities provided access to historical versions of any of their policies.

3.2.2 Engaging with Company Through Questions or Complaints

We examined whether WeChat China and WeChat International provided specific contact information so that users could communicate with the company, which they may want to do in order to better understand how the platform captures, processes, or stores their personal information.

Both WeChat China and WeChat International had dedicated legal contact information, though neither identified a specific named privacy officer or point of contact. WeChat International explicitly noted that EU residents “have the right to lodge a complaint with [their] country’s data protection authority.”

While WeChat China and WeChat International promised to protect users’ rights to access, correct, and delete personal information, they both included caveats.44 WeChat China provided a detailed operational guide in its privacy policy on how users can access, amend, or delete personal information and on how to withdraw permission within the application. In addition to data access, correction, and erasure, WeChat International outlined data portability features which were exclusively reserved for EU users.45

3.2.3 Capture of Personal Information

Many social media services are designed to collect vast quantities of personal information, some of which is intimately sensitive in nature. We examined whether WeChat China and WeChat International clearly indicated the types of information that they collected as well as whether they provided rationales for the collections. We also examined if there were specifications for where information was stored in these policies.

WeChat China and WeChat International policies distinguished between sensitive personal information and non-personal information. WeChat China’s policy did not provide a definition of personal information but did indicate the types of information it collected and, from among those, which constituted sensitive information.46 Notably, WeChat China asserted that in addition to the types of data it outlined in its policies, the company could collect and process relevant personal information without asking for users’ content under various circumstances.47 WeChat International defined personal information as “any information, or combination of information, that relates to you, that can be used (directly or indirectly) to identify you.”48 WeChat International further specified what types of information were regarded as “shared information” (i.e., “information about you or relating to you that is voluntarily shared by you on WeChat”). Of particular note, WeChat International recognized a difference between ‘regular’ personal information and ‘sensitive’ personal information. Sensitive personal information included that about “your race or ethnic origin, religious or philosophical views or personal health” and “is subject to stricter regulation than other types of Personal Information…Before communicating any Personal Information of a sensitive nature within WeChat, please consider whether it is appropriate to do so.”49 The WeChat International’s definition of sensitive personal information is contrasted against that in WeChat China’s, where sensitive information includes a user’s mobile phone number, voice biometrics, location information, movement (e.g., number of steps), contact/friends information, and payment records.50 Furthermore, whereas search data were explicitly defined as personal information in WeChat International’s policies, WeChat China did not make an equivalent specification.

WeChat International stated that chat data, which constitutes “[c]ontent of communications between you and another user or group of users” is “stored on your device and the devices of the users that you have sent communications to. We do not permanently store this information on our servers and it only passes through our servers so that it can be distributed to users you have chosen to send communications to.”51 WeChat China’s statement on the duration of data retention was relatively vague, noting that “in general, we will only keep your personal information for the time necessary to achieve a specific purpose.”52 Whereas WeChat International explained it only retained chat data for 120 hours,53 WeChat China cited only two examples (i.e., “mobile phone number” and “information in Moments”54) to show how long it stored personal information. Specifically, users’ mobile phone numbers are stored for as long as they use WeChat, and information in Moments is stored until a user deletes the corresponding information.

WeChat China noted that all personal information collected within the territory in China would be stored in China. For users of WeChat International, the personal information would be transferred to, stored, or processed in Ontario, Canada or in Hong Kong. The company provided justifications noted for the choice of each location.55

3.2.4 Disclosures of Information

One of the growing concerns over the global expansion of Chinese Internet companies which have operational entities in mainland China and overseas is whether user data collected outside of China is shared with members and affiliates of the company in China, China-based third-parties, or Chinese authorities.56 The prospect of such sharing is particularly significant given that technical research, discussed in Section 2, revealed that non-China-registered accounts’ information was being subject to content surveillance for the purpose of extending what was censored for China-registered accounts. As such, we examined WeChat China’s and WeChat International’s policies to determine the extent to which the companies asserted their rights to disclose collected information to third-parties and the conditions under which such disclosures were authorized.

We found that the clarification varied between the two entities with respect to the disclosure of information to third-parties and members or affiliates of Tencent. WeChat China made it clear that it would not share users’ personal information with third-parties outside of Tencent.57 However, it was left unclear how personal information would be shared among services owned by Tencent. We found the opposite in WeChat International’s policies, where there were sometimes very clear specifications about which Tencent-related group companies the application could share personal information.58 WeChat International acknowledged that it shared user data with certain third-party service providers, as well, without specifying with whom or what types of information were shared.

WeChat China and WeChat International acknowledged that they may share information with law enforcement organizations under certain conditions, though the level of specificity varies between the two companies. WeChat China strongly implied that it would disclose the user’s personal information to law enforcement organizations without specifying whether such disclosure would be conducted under a court order or which organizations would potentially receive information (e.g., police department based in the signing place of WeChat China agreements versus police departments based in any part of China).59 Moreover, the circumstances under which the company “may share, transfer, or publicly disclose personal information without prior consent of the subject of the personal information” were broadly defined.60 Though the entity did not specify which jurisdictions it would not share information with, WeChat China did acknowledge that the governing jurisdiction was mainland China.

In contrast, WeChat International stated that any disclosure of information to “government, public, regulatory, judicial and law enforcement bodies or authorities” would be carried out where the company “[is] required to comply with applicable laws or regulation, a court order, subpoena or other legal process, or otherwise have a legal basis to respond to a request for data from such bodies, and the requesting entity has valid jurisdiction to obtain [the user’s] personal information.”61 The company did not commit to informing users about such disclosures. Similar to WeChat China’s policies, WeChat International did not specify any countries with whom data would not be shared.

3.2.5 Behaviours of Hashing and Blocking User-Generated Content

Social media companies operating in China are known to control sensitive information in compliance with local laws and regulations.62 As of early 2020, there are increasing concerns about how Chinese-owned companies might exploit data generated outside mainland China or among their international users in the face of domestic political pressure, such as to block the availability of certain content, or conduct surveillance of particular persons or classes of communications. We examined whether there was any mention of, or justification for, performing hashing of communications content for the purpose of facilitating blocking access to content in either of WeChat China’s or WeChat International’s policies.

We found that both companies discussed the possibility of retaining and using content for several purposes. WeChina China acknowledged that it “may use information collected by certain features for […] other services” and that such practices were justified on the basis of enabling performance and service optimization.63 In addition to stating that WeChat International and its affiliate companies “are allowed to retain and continue to use Your Content after you stop using WeChat,” WeChat International wrote in its terms of services that:

“you are giving us and our affiliate companies a perpetual, non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide licence to use Your Content (with no fees or charges payable by us to you) for the purposes of providing, promoting, developing and trying to improve WeChat and our other services, including new services that we may provide in the future… As part of this licence, we and our affiliate companies may, subject to the our WeChat Privacy Policy, copy, reproduce, host, store, process, adapt, modify, translate, perform, distribute and publish Your Content worldwide in all media and by all distribution methods, including those that are developed in the future.”

Further, WeChat International might justify its hashing of content on the basis that doing so constitutes services improvement and security protections. Specifically, the company’s policies stated that WeChat “may be required to retain or disclose Your Content in order to enforce these Terms or to protect any rights, property or safety of ours, our affiliate companies or other users of WeChat.”64

In terms of blocking content, WeChat China asserted that Tencent would act in accordance with laws and regulations based on its “reasonable judgement” to “remove or obscure relevant contents at any time without notice, impose punishment on the violating account including but not limited to warning, restriction or prohibition of the use of some or all of the functions, account banning or cancellation, and announce the results of treatment.”65 Similarly, WeChat International stated that it “may review (but make no commitment to review) content (including any content posted by WeChat users) or third party programs or services made available through WeChat to determine whether or not they comply with our policies, applicable laws and regulations or are otherwise objectionable. We may remove or refuse to make available or link to certain content or third party programs or services if they infringe intellectual property rights, are obscene, defamatory or abusive, violate any rights or pose any risk to the security or performance of WeChat.”

3.2.6 Data Protection Office Non-Response

We contacted WeChat’s international data protection office on January 20, 2020, using the contact email that was provided in the company’s international Privacy Policy.66 We did not receive a response from the Office, including even an acknowledgment that they received our initial letter, by February 3, 2020. As a result, we sent a reminder email on February 3, 2020; as of writing, we have still not received any response from WeChat’s international data protection office to the questions posed to them.

3.3 Discussion

It was easy to identify and access the international and China-specific versions of the privacy policies, terms of service, and associated documents linked with the WeChat service. Both China-registered and non-China-registered accounts were presented with data access, correction, and deletion capabilities, indicating that the company was compliant with basic rights afforded under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), Canada’s data privacy legislation. Similar rights are extended to persons living in European countries which are subject to the GDPR, or countries with GDPR-like legislation.

While it is clear from public information that content may be blocked for China-registered accounts, it is unclear how international data is used to enable content blocking or the policy rationale which permits the sharing of data used for blocking between international and China regions of WeChat. As per their policies, WeChat International does reserve the right to block content for its international users. Specifically the company:

“may review (but make no commitment to review) content (including any content posted by WeChat users) or third party programs or services made available through WeChat to determine whether or not they comply with our policies, applicable laws and regulations or are otherwise objectionable. We may remove or refuse to make available or link to certain content or third party programs or services if they infringe intellectual property rights, are obscene, defamatory or abusive, violate any rights or pose any risk to the security or performance of WeChat.”67

While WeChat China’s policy documents clearly permit a wide range of blocking and WeChat International’s policies appear to permit some sort of blocking, these policies at best explain the motivation for content surveillance of non-China-registered users but do not enable it. In the remainder of this section, we discuss whether according to policy documents WeChat International is permitted to analyze non-China-registered users’ data for political sensitivity and whether WeChat International is permitted to share users’ data or the results of this analysis to entities in China.

3.3.1 Enabling Content Surveillance

The international public-facing policy documents do include language that could permit communications content surveillance and, therefore, prospectively the hashing of the contents of communications for the purposes of developing or enhancing WeChat’s censorship system. Specifically, the international policy documentation reveals that WeChat might review content, which could be interpreted as permitting the company to assess content to derive hashes from it. The company, elsewhere, acknowledges that individuals may share “sensitive information” on WeChat, “such as information about your race or ethnic origin, religious or philosophical views or personal health” and that “content and information that you input to WeChat, such as photographs or information about your school or social activities, may reveal your sensitive Personal Information to others.”68 WeChat is not providing an exclusive listing of what constitutes sensitive information; even what is listed, however, might be inclusive of political speech where it is aligned with philosophical views. Further, sensitive information exists in multiple kinds of shared content and not just the text that is typed. As such, sensitive information—including communicating certain philosophical views—might be found in photos and, presumably, documents or other kinds of files.

Analysis of international users’ communications are also authorized in the privacy policy and terms of service documents that they agree to. WeChat International includes a standard, broadly encompassing, class of language which authorizes them to transmit users’ communications without running afoul of copyright claims. Specifically, the company’s public-facing documentation includes:

“you are giving us and our affiliate companies a perpetual, non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide licence to use Your Content (with no fees or charges payable by us to you) for the purposes of providing, promoting, developing and trying to improve WeChat and our other services, including new services that we may provide in the future… As part of this licence, we and our affiliate companies may, subject to the our WeChat Privacy Policy, copy, reproduce, host, store, process, adapt, modify, translate, perform, distribute and publish Your Content worldwide in all media and by all distribution methods, including those that are developed in the future.”69

WeChat might further justify analyzing content based on the assertion that the company “may be required to retain or disclose Your Content in order to enforce these Terms or to protect any rights, property or safety of ours, our affiliate companies or other users of WeChat.”70 Content might be retained per this language, as well as assessed, if it is found to infringe upon “any rights, property or safety of ours” or the company’s “affiliate companies or other users of WeChat.” Specifically, without a better understanding of the way(s) in which WeChat’s international and China operations are associated, such as whether they constitute affiliate companies or China-registered WeChat accounts are “other users of WeChat” per the international company’s terms of service and privacy policy, it is challenging to definitively know if these elements of the company’s international public policy documentation authorize the analysis the content of international users’ communications for that which is ‘sensitive’ in China, or the hashing of such content of communications, or the sharing the results with the Shenzhen-domiciled element of the company.

In contrast, the terms of services and privacy policies WeChat enforces on its China-registered accounts include a clear statement that would authorize the company to conduct content surveillance for the purpose of content blocking. Specifically, WeChat China’s terms of services state that:

“If Tencent finds or receives any report or complaint from others against the user on violation to this Agreement, Tencent is entitled to remove or obscure relevant contents at any time without notice, impose punishment on the violating account including but not limited to warning, restriction or prohibition of the use of some or all of the functions, account banning or cancellation, and announce the results of treatment.” 71

In line with WeChat International’s documents which justify the analysis of international users’ communications for security and performance improvement reasons, the language used in the policy documents pertaining to WeChat’s China-registered accounts allows Tencent to read and analyze users’ communications.72

In conclusion, it remains highly plausible that WeChat could attempt to justify subjecting its international users’ communications to content surveillance based on the contents of the company’s public-facing policy document. Moreover, the company can clearly engage in content surveillance of the communications transmitted using China-registered accounts. To be entirely certain about the policy rationale undergirding content surveillance of international users’ communications, however, the company’s international data protection officer would have needed to reply to our letter. We have not received a response as of this report’s publication date.

3.3.2 Enabling Content or Metadata Disclosure

In specifically assessing the policies to ascertain whether they do, or do not, permit the disclosure of international users’ communications content or metadata to parties in China, we found that the permissibility of such disclosures remained ambiguous. On the one hand, the international entity denoted a specific list of subsidiary international organizations with whom it might disclose information, and then more broadly identified classes of external organizations—such as those that enable SMS delivery or VoIP functionality—that might receive information about the user or their usage of WeChat. It is possible that these subsidiary or third-party organizations might, themselves, have disclosure policies that include sharing information about international users’ communications with a China-based organization that ultimately routes data to WeChat’s China-based entity. However, if this is the case, and presuming it is typical behaviour, then the failure to specify such practices would be misleading to someone who had read the privacy policy and terms of service with the intent of learning how the company typically handled users’ communications. Should such disclosures be sufficiently irregular that they do not merit including information about them in the public-facing policy documents, then WeChat could and should notify individuals that data is being disclosed when it takes place, such as through in-app dialogues or automated chat sessions initiated by the company. Ultimately, then, while it is possible that the public-facing policy documents might authorize the sharing of international users’ data with WeChat China, the prospect of this sharing is not clear or apparent from reading these policies.

Similarly ambiguous is how WeChat’s China-based entity handles communications between its China and international users. The policy documents pertaining to WeChat’s users with a China-registered account state that the company “may use information collected by certain features for our other services.” Whereas these policy documents make it clear that Tencent does not share or transfer personal information to third parties outside of Tencent, it is left unclear how or whether information and contents of internationally-based users of Tencent-affiliated services are shared within the company.

In summary, it remains unclear on what basis the hashes of international users’ communications might be disclosed to WeChat China. To be certain on what basis, if any, WeChat justifies the sharing of hashes between the international and China-specific iterations of WeChat, the company’s international data protection officer would have had to reply to the letter we issued to them. As of publication, however, the company has failed to even acknowledge their receipt of the messages we have sent them, let alone respond to the questions we posed to the company.

Part 4 – Data Access Request Assessment

Tencent is subjected to the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) because it has a substantial commercial connection to Canada by merit of doing business with persons residing in Canada and because some o f the company’s data centres are located in Canada.73 Principle 4.9 of PIPEDA outlines Canadians’ access and correction rights; Canadians have a right to “be informed of the existence, use, and disclosure of their personal information and be given access to that information.”74 Individuals may have to prove their identity so that companies can retrieve their information. Organizations must provide some response to the requester within thirty days and may (as part of that response) inform requesters that the company is availing itself of an additional thirty days to prepare a response. Access should be provided at a minimum, or zero, cost.

In this section of the report, we discuss and assess the findings which emerged from filing a PIPEDA-based data access request upon Tencent’s international business. Overall, while we found that there was a limited data export tool that employees were quick to help us use, the employees would not respond to questions about data not contained in the export tool, inclusive of how images were hashed, or whether such hashes were shared with WeChat China.

4.1 Methodology

One of the project researchers created a non-China-registered WeChat account. From this account, the researcher communicated with other accounts which our team created, all of which were registered internationally.75 Specifically, the researcher transmitted unique and sensitive chat messages, documents, and images in a group chat which contained two other non-China-registered accounts. To confirm that the hashes of the documents and images were added to the hash index, a pair of experiments were conducted, as discussed in Section 2.

We used PIPEDA-based data access requests to better understand the kinds of personal information that Tencent collects when an international user installs WeChat and uses the service. In particular, we explored whether such requests could be used to reveal to international users that the content of their communications were being used to develop the hash index which was used to censor the communications of China-registered accounts.

The researcher filed two rounds of personal information requests. The first round entailed two separate emails: one to Tencent’s international data protection office, and the second to Tencent’s China-based data protection office. The second round entailed a single follow-up email to Tencent’s international data protection office.

4.1.1 Round One Data Access Request

The first request asked questions about the different kinds of data which might be collected in the course of using WeChat, inclusive of geolocation information, IP address logs, subscriber information, personally identifiable information, as well as any information pertaining to communications between users, any MD5 hashes of the content of communications exchanged using WeChat, or whether any communications sent using WeChat had been found to violate Tencent’s terms of service and, if so, whether such violations pertained to violations associated with users who were located in China. The request also asked the company to disclose whether the content of any communications, or hashes derived from such communications, had been used to enable or optimize the detection of terms of service violations for users located in the People’s Republic of China or any other jurisdiction. The request, finally, asked Tencent to disclose if any personal information, or information about the researcher’s account or devices, had been shared with any other third-parties and, in the request made to Tencent Singapore, specifically whether it had been shared or disclosed with Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Company Limited. Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Company Limited is the portion of the company that is domiciled in the People’s Republic of China and, thus, is required to comply with Chinese law that mandates the blocking of particular content that is communicated using WeChat. The letter cited PIPEDA and informed Tencent of its requirement to respond within thirty days and at a minimal cost.

Copies of this request as sent to the Tencent Shenzhen and Tencent Singapore data protection offices are available in Appendices B and C, respectively.

4.1.2 Round Two Data Access Request

After receiving an initial response—discussed in Section 4.2—another letter was sent which reiterated requests for the below data:

- Communications between the researcher and other users.

- The geographic location where data which the researcher contributed to the WeChat social network was stored and, more specifically, whether any of the data was stored in the People’s Republic of China.

- Social networking information, inclusive of MD5 hashes or other hashes computed upon the researcher’s chat messages, images, or files sent using the service.

- Results indicating whether any of the chat messages, images, or files sent using the service had been determined to violate the company’s terms of service and, if so, the basis for which these messages were categorized as violating the terms of service.

In cases where the data was not retained, the researcher asked that Tencent positively confirm that the data was not retained.

The follow-up letter also asked Tencent to disclose “whether (and, if so, which of) any of my chat messages, images, or files sent using your service, or any hashes computed upon these items, have been used for the purposes of detecting terms of service violations for users located in the People’s Republic of China or any other jurisdiction” as well as “whether (and, if so, which of) any of my chat messages, images, or files sent using your service, or any hashes computed upon these items, have been shared with, or disclosed to, Shenzhen Tencent Computer Systems Company Limited either by Tencent International Service Pte. Ltd. or a subsidiary, and to which other parties in China or outside China (inclusive of all subsidiaries) with whom this data has been shared.”

A copy of this letter is in Appendix D.

4.2 Data

The first data access request (“PIPEDA request”) was sent on November 29, 2019, to the email address associated with the Tencent Shenzhen and Tencent Singapore data protection offices. Our interactions with Tencent Singapore took place according to the following timeline:

- December 2: Tencent provided instructions to access and use WeChat’s “Export Personal Data” tool

- December 2: Researcher informed Tencent that, although they were using the latest version of the app, they could not find an “Export Personal Data” tool using the provided instructions

- December 5: Tencent responded that they can facilitate the data export but, to do so, the researcher had to verify their identity. Identity verification was based on providing eight different items for verification. Tencent requested that the researcher provide as many as possible

- December 5: Researcher provided Tencent with the eight items for verification

- December 16: Tencent responded by directing the researcher to paste a link76 into a WeChat chat and to open the URL in WeChat to export the personal data

- December 18: The researcher followed the instructions. Using the export tool accessible from the link, the researcher was required to confirm their email address. After confirming their email address, the researcher was automatically emailed a link to a web page that provided a downloadable *.zip file that contained information pertaining to the researcher’s use of the application

The *.zip included the following information:

- Personal account information: WeChat ID, Registration Region, Linked Accounts (i.e., email attached to the account), Registration Time, and Phone Number.

- Contact Data: Friends and Group Chat Contacts. No accounts were listed under the latter category.77

- Moments Data: My Moments, My Comments and Likes, Hide My Moments, and Hide User’s Moments. No information was provided in this category, presumably because the researcher did not use these aspects of WeChat.

- Location and Login Information: Location Information and Login Devices. The latter identified the mobile device the researcher used while interacting with WeChat, whereas no information was presented for the former category.

Information which was requested in the initial letter but not provided in the response included:

- IP address log information

- Information pertaining to whether and, if so, how the researcher’s communications data was used to generate the censorship index for China-registered accounts

- Information of whether information about the researcher—inclusive of account information, communications content, or MD5 hashes of their content—had been shared with any third-parties

The second round of the data access request sent on December 18 reiterated that the researcher sought access to information discussed in Section 4.1.2. No subsequent communications have been received by Tencent Singapore as of the time of publication.

At no point did the researcher receive a response to the letter that they issued to Tencent Shenzhen.

4.3 Discussion

The data which Tencent Singapore provided to the researcher fell short of the information which had been requested. Most notably, it excluded information that was principally sought concerning the extent to which, and rationales upon which, derived elements of the researcher’s communications might have been communicated to other parties such as Tencent Shenzhen. This failure took place despite the researcher’s repeated engagements with Tencent Singapore employees; they were actively involved in communicating with the researcher to guide them to the Export Personal Data tool, but failed to provide substantive communications concerning the most pressing of the researcher’s questions about the company’s data handling practices.

Tencent Singapore’s response, which directed users to a data export tool, parallels past experiences of researchers who have sought access to information retained by other companies, including fitness tracker companies and social media companies. Specifically, data export tools have been shown to not include all of the information that users provide to services, and companies routinely fail to answer questions about data collection, processing, and storage beyond what is presented through data export tools.78 However, in the case of Tencent there is evidence—as denoted in Section 2—that either the Singapore or Shenzhen part(s) of the company are using non-China-registered users’ communications to develop a hash index that is subsequently applied to censor communications between a subset of Tencent’s user base: those who have registered their accounts in China.