Key Findings

- Dark Basin is a hack-for-hire group that has targeted thousands of individuals and hundreds of institutions on six continents. Targets include advocacy groups and journalists, elected and senior government officials, hedge funds, and multiple industries.

- Dark Basin extensively targeted American nonprofits, including organisations working on a campaign called #ExxonKnew, which asserted that ExxonMobil hid information about climate change for decades.

- We also identify Dark Basin as the group behind the phishing of organizations working on net neutrality advocacy, previously reported by the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- We link Dark Basin with high confidence to an Indian company, BellTroX InfoTech Services, and related entities.

- Citizen Lab has notified hundreds of targeted individuals and institutions and, where possible, provided them with assistance in tracking and identifying the campaign. At the request of several targets, Citizen Lab shared information about their targeting with the US Department of Justice (DOJ). We are in the process of notifying additional targets.

Introducing Dark Basin

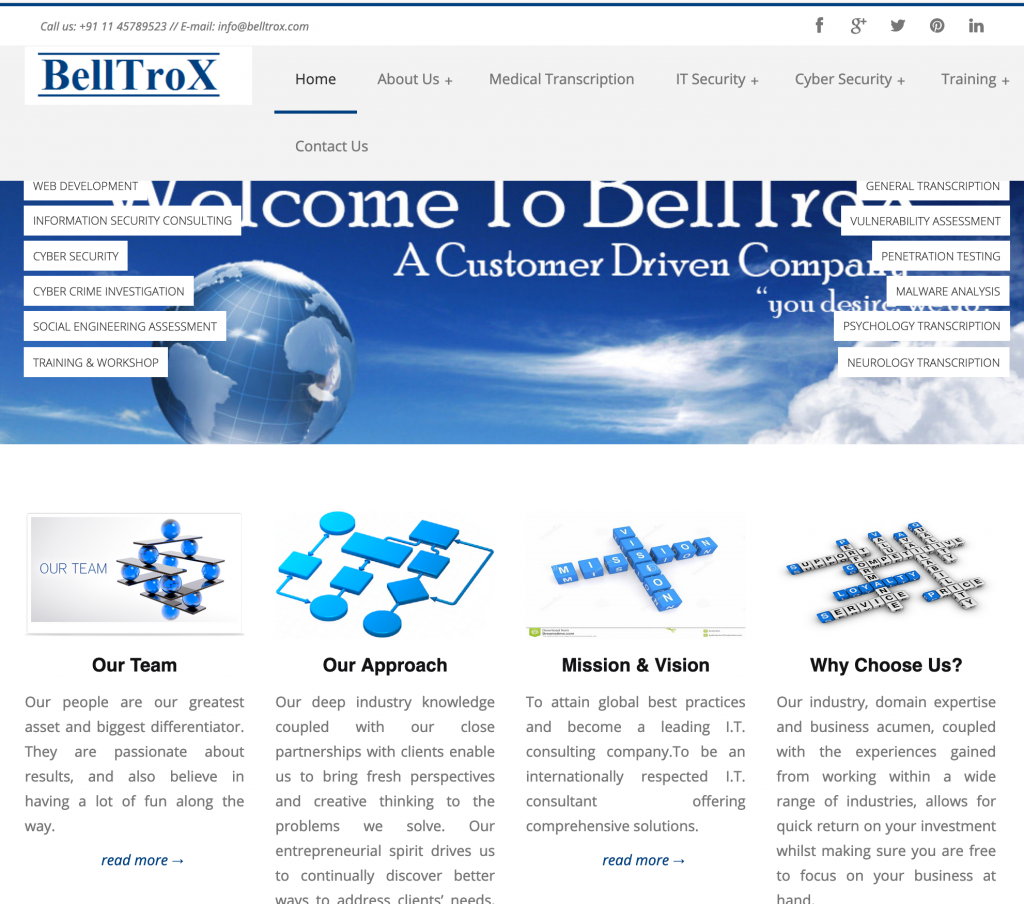

We give the name Dark Basin to a hack-for-hire organization that has targeted thousands of individuals and organizations on six continents, including senior politicians, government prosecutors, CEOs, journalists, and human rights defenders. With high confidence, we link Dark Basin to BellTroX InfoTech Services (“BellTroX”), an India-based technology company.

Over the course of our multi-year investigation, we found that Dark Basin likely conducted commercial espionage on behalf of their clients against opponents involved in high profile public events, criminal cases, financial transactions, news stories, and advocacy. This report highlights several clusters of targets. In future reports, we will provide more details about specific clusters of targets and Dark Basin’s activities.

Thousands of Targets Emerge

In 2017, Citizen Lab was contacted by a journalist who had been targeted with phishing attempts and asked if we could investigate. We linked the phishing attempts to a custom URL shortener, which the operators used to disguise the phishing links.

We subsequently discovered that this shortener was part of a larger network of custom URL shorteners operated by a single group, which we call Dark Basin. Because the shorteners created URLs with sequential shortcodes, we were able to enumerate them and identify almost 28,000 additional URLs containing e-mail addresses of targets. We used open source intelligence techniques to identify hundreds of targeted individuals and organizations. We later contacted a substantial fraction of them, assembling a global picture of Dark Basin’s targeting.

Our investigation yielded several clusters of interest that we will describe in this report, including two clusters of advocacy organizations in the United States working on climate change and net neutrality.

While we initially thought that Dark Basin might be state-sponsored, the range of targets soon made it clear that Dark Basin was likely a hack-for-hire operation. Dark Basin’s targets were often on only one side of a contested legal proceeding, advocacy issue, or business deal.

Research Collaborations & Official Notification

Links to an Indian Operator

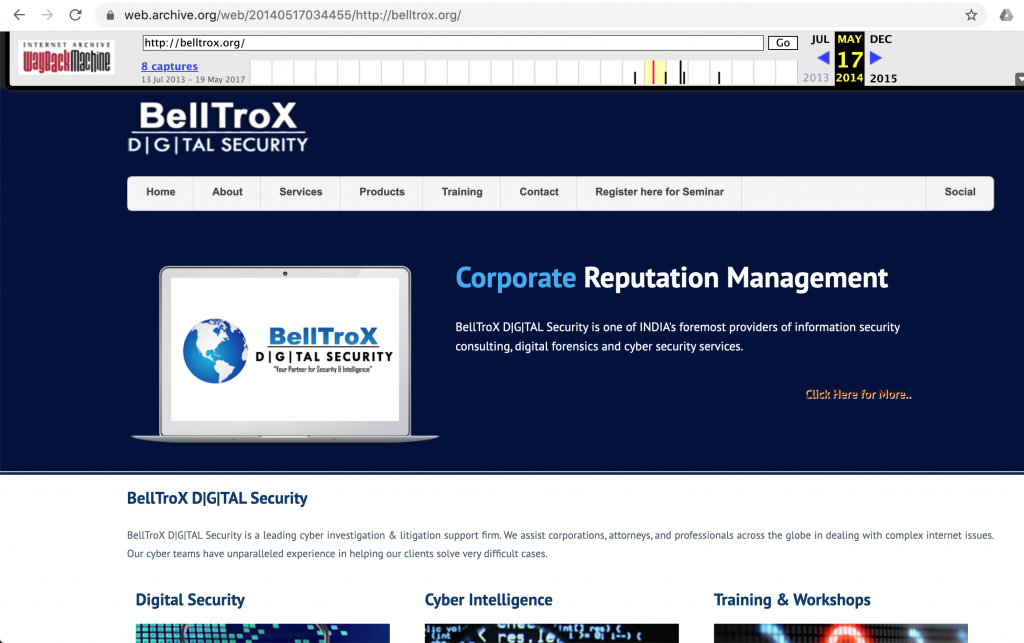

We link Dark Basin’s activity with high confidence to individuals working at an Indian company named BellTroX InfoTech Services (also known as “BellTroX D|G|TAL Security,” and possibly other names). BellTroX’s director, Sumit Gupta, was indicted in California in 2015 for his role in a similar hack-for-hire scheme.

Links to India

Timestamps in hundreds of Dark Basin phishing emails are consistent with working hours in India’s UTC+5:30 time zone. The same timing correlations were found by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) in a prior investigation of phishing messages targeting net neutrality advocacy groups, which we also link to Dark Basin.

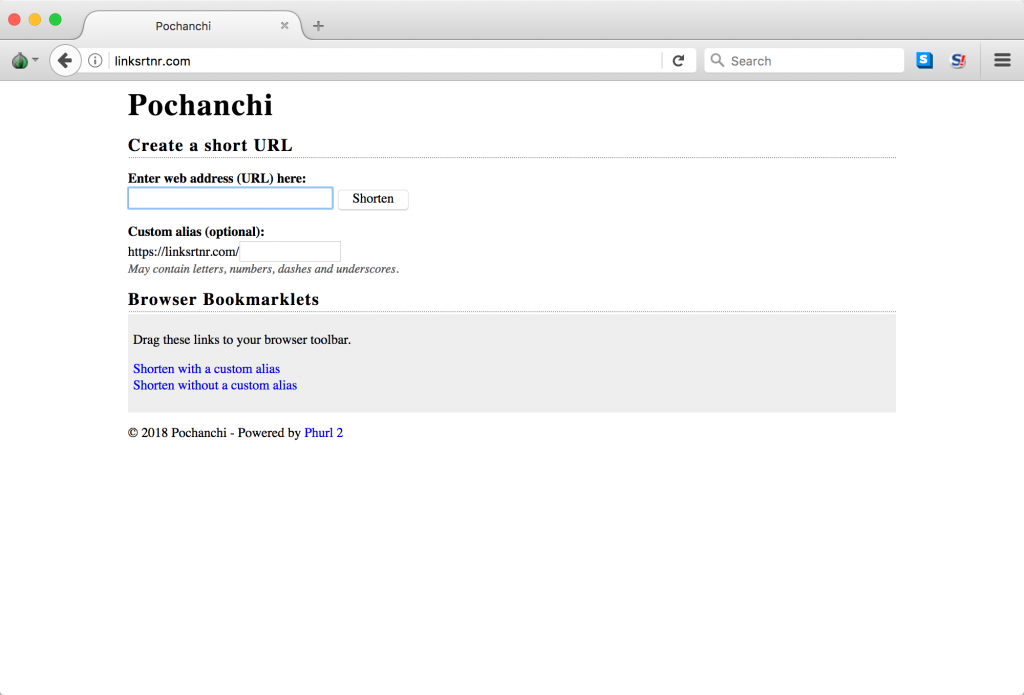

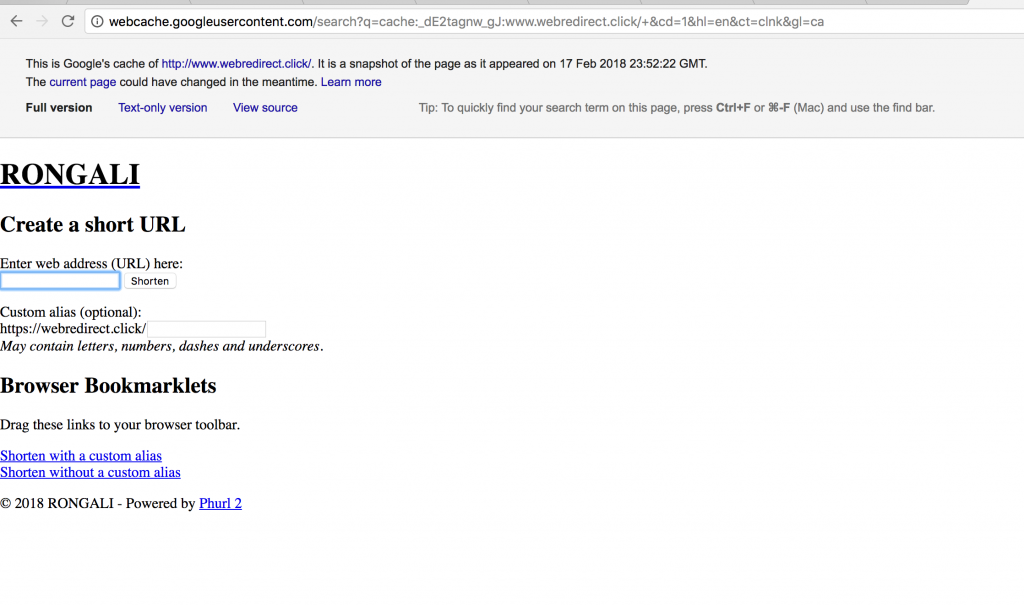

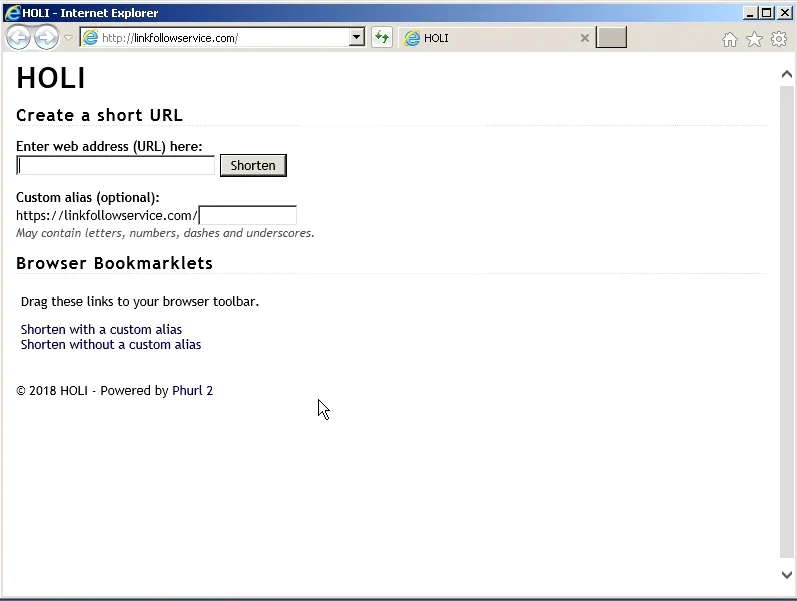

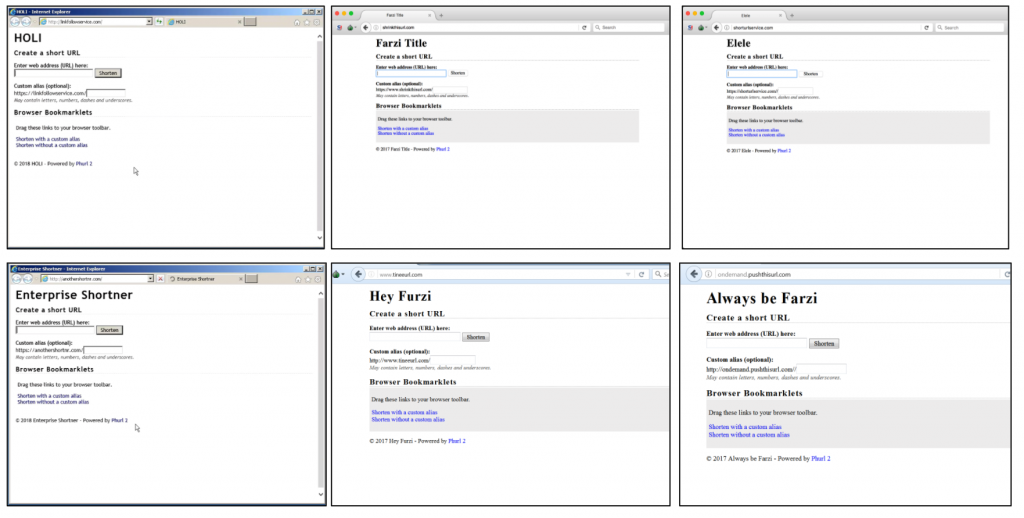

Several of Dark Basin’s URL shortening services had names associated with India: Holi, Rongali, and Pochanchi (Table 1). Holi is a well-known Hindu celebration also known as the “festival of colours,” Rongali is one of the three Assamese festivals of Bihu, and Pochanchi is likely a transliteration of the Bengali word for “fifty-five.”

Table 1: Three of the URL shortener services used by Dark Basin.

Additionally, Dark Basin left copies of their phishing kit source code available openly online, as well as log files showing testing activity. The logging code invoked by the phishing kit recorded timestamps in UTC+5:30, and log files show that Dark Basin appeared to conduct some testing using an IP address in India.

Links to BellTroX

Along with our collaborators at NortonLifeLock, we have unearthed numerous technical links between the campaigns described in this report and individuals associated with BellTroX. These links lead us to conclude with high confidence that Dark Basin is linked to BellTroX.

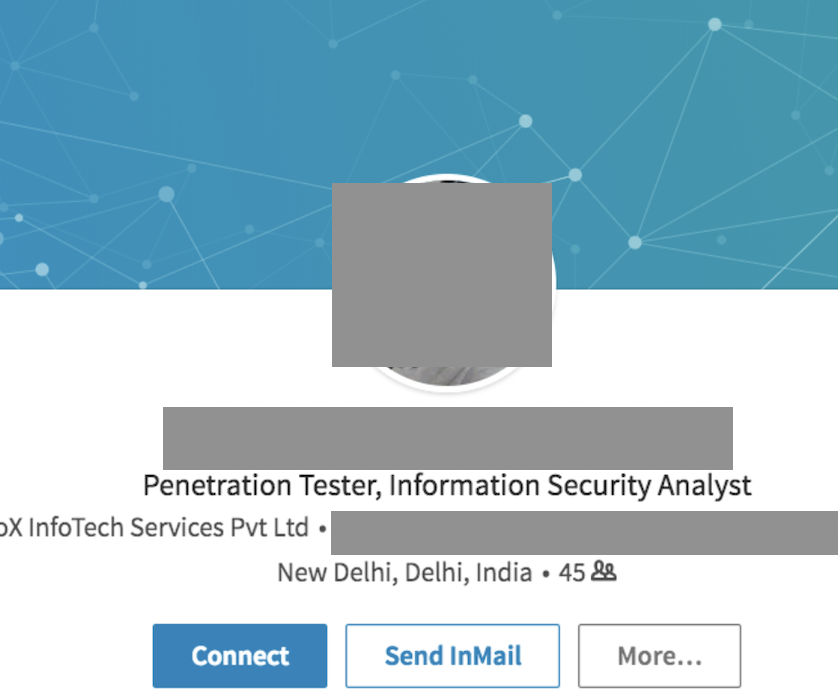

We were able to identify several BellTroX employees whose activities overlapped with Dark Basin because they used personal documents, including a CV, as bait content when testing their URL shorteners. They also made social media posts describing and taking credit for attack techniques containing screenshots of links to Dark Basin infrastructure. BellTroX and its employees appear to use euphemisms for promoting their services online, including “Ethical Hacking” and “Certified Ethical Hacker.” BellTroX’s slogan is: “you desire, we do!”

On Sunday, June 7th 2020 we observed that the BellTroX website began serving an error message. We have also observed that postings and other materials linking BellTroX to these operations have been recently deleted.

Technical evidence of further links between BellTroX and Dark Basin are detailed in Appendix A. Indicators of Compromise are available in Appendix B.

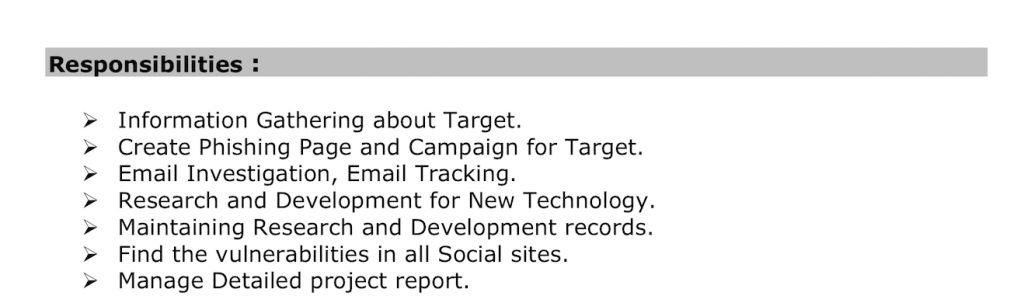

Table 2: Excerpt from the CV (left) of an individual matching the name of a then-BellTroX employee (right) shared using a shortener link. The “Responsibilities” described match the activities of Dark Basin.

BellTroX’s Director and Previous Hack-For-Hire Schemes

Further, in 2015, the US DOJ indicted several US-based private investigators and an Indian national, Sumit Gupta (whom the DOJ notes also uses the alias Sumit Vishnoi), for their role in a hack-for-hire scheme. To our knowledge, Gupta was never arrested in relation to the indictment. An aggregator of Indian corporate registration data lists Sumit Gupta as the director of BellTroX, and online postings by a “Sumit Vishnoi” contain references to BellTroX. The actions described in that indictment, including the extensive relationships with private investigators, are similar to those we ascribe to BellTroX.

Dark Basin’s Connections to Private Investigators

We have observed Dark Basin’s activities over several years, including the social media activities and posts of individuals working at BellTroX. Some of the individuals listed on LinkedIn as working for BellTroX mention activities that indicate hacking capabilities.

BellTroX staff activities listed on LinkedIn include:

- Email Penetration

- Exploitation

- Corporate Espionage

- Phone Pinger

- Conducting Cyber Intelligence Operation

BellTroX’s LinkedIn pages, and those of their employees, have received hundreds of endorsements from individuals working in various fields of corporate intelligence and private investigation.

BellTroX and its employees received endorsements from individuals listing themselves as:

- An official in the Canadian government.

- An investigator at the US Federal Trade Commission and previously a contract investigator for US Customs and Border Patrol.

- Current local and state law enforcement officers.

- Private investigators, many with prior roles in the FBI, police, military and other branches of government.

Despite a previous DOJ indictment of the BellTroX Director, as well as indictments in other hack-for-hire cases, the companies that provide these services publicly promote their activities. This suggests that companies and their clients do not expect to face legal consequences and that the use of hack-for-hire firms may be standard practice within the private investigations industry. A LinkedIn endorsement may be completely innocuous, and is not proof that an individual has contracted with BellTroX for hacking or other activity. However it does raise questions as to the nature of the relationship between some of those who posted endorsements and BellTroX.

Targeting American Nonprofits, Journalists

Dark Basin has a remarkable portfolio of targets, from senior government officials and candidates in multiple countries, to financial services firms such as hedge funds and banks, to pharmaceutical companies. Troublingly, Dark Basin has extensively targeted American advocacy organizations working on domestic and global issues. These targets include climate advocacy organizations and net neutrality campaigners.

Targeting American Environmental Organizations

We discovered a large cluster of targeted individuals and organizations that were engaged in environmental issues in the US. In the fall of 2017, Citizen Lab made contact with these groups and began working with them to determine the nature and scope of the targeting. We determined that these organizations were all linked to the #ExxonKnew campaign, which highlights documents that, the advocacy organizations argue, point to Exxon’s decades-long knowledge of climate change. According to the New York Times, the #ExxonKnew campaign has led to “exposés of the company’s research into climate change, including actions it took to incorporate climate projections into its exploration plans while playing down the threat.” The New York Times describes an intense legal battle between ExxonMobil, multiple states’ attorneys general, and organizations engaged in the #ExxonKnew campaign.

Targeted organizations consenting to be named in this report include:

- Rockefeller Family Fund

- Climate Investigations Center

- Greenpeace

- Center for International Environmental Law

- Oil Change International

- Public Citizen

- Conservation Law Foundation

- Union of Concerned Scientists

- M+R Strategic Services

- 350.org

At their request, we are not naming all targets within this cluster.

We provided the targets with search queries to find Dark Basin emails and instructed them on how to use these queries to gather emails from their inboxes. While this methodology cannot generate a comprehensive set of all Dark Basin phishing attempts, it provided retrospective data that helped us correlate the timing of phishing emails with key events in the #ExxonKnew campaign. We identified these key events with the assistance of targeted organizations, as well as a timeline released by ExxonMobil. We noted that targeting increased around certain key events, as illustrated below.

A Stolen Email?

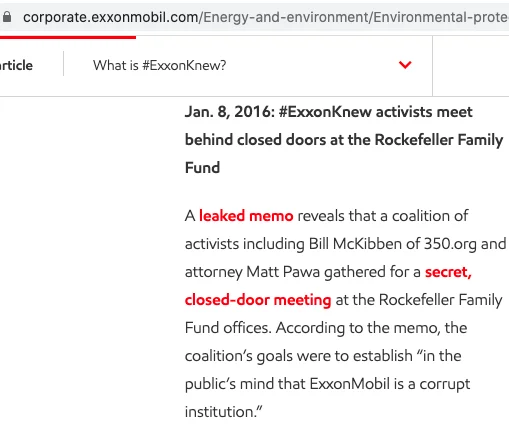

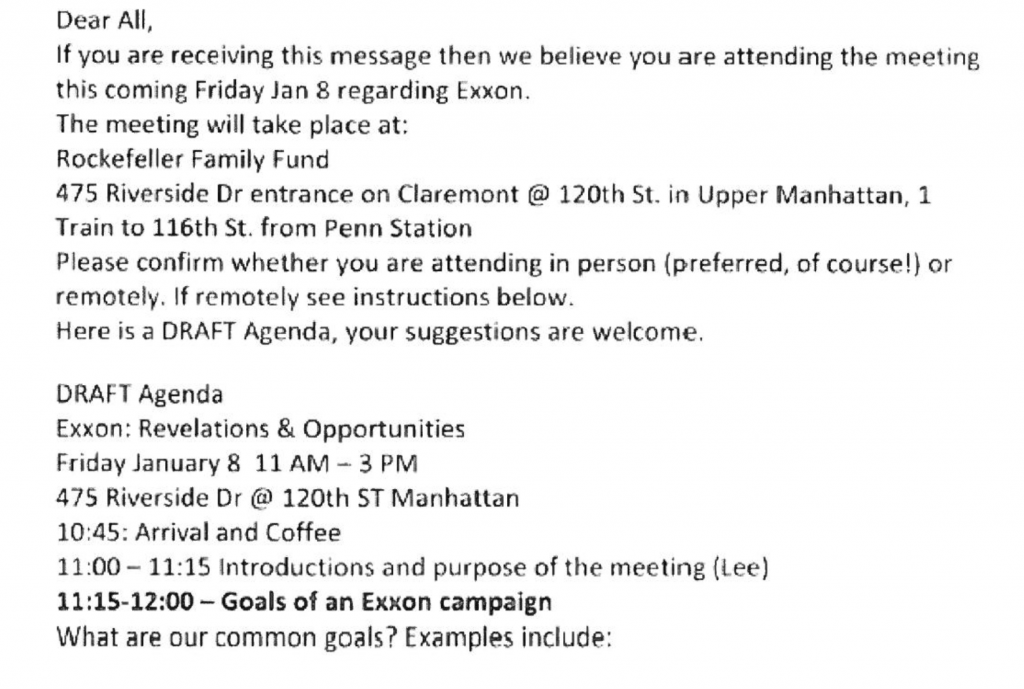

In January 2016, a group of environmental organizations and funders met privately to discuss the #ExxonKnew campaign. A private email inviting campaigners to the January meeting (the “January Email”) was subsequently leaked by unknown parties to two newspapers. The January Email was quoted in a story entitled “Exxon Fires Back at Climate-Change Probe” on April 13, 2016 in the Wall Street Journal, and a day later a picture of a printout of the January Email was published in the Free Beacon.

After a reporter queried the attendees about the secret meeting in March 2016, we found no further phishing emails until the New York Attorney General made a filing alleging evidence of “potential materially false and misleading statements by Exxon” in June 2017. Targeting also spiked again shortly before New York City(2) filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil in January 2018.

Table 3: ExxonMobil’s timeline of the advocacy campaign, highlighting the January Email (left) and an excerpt of the “leaked” January Email (right).

The leak of the January 2016 Email, as well as suspicious emails noticed by campaigners, led some present at the meeting to suspect their private communications may have been compromised. We later determined that all but two recipients of the leaked January Email were also Dark Basin targets.

We also note multiple other instances of internal documentation related to individuals publicly connected to these campaign issues appearing in the press.

Well-Informed Targeting

Dark Basin sent phishing emails to targets’ personal and institutional email accounts. They targeted individuals involved in the #ExxonKnew campaign, as well as #ExxonKnew campaigners’ family members. In at least one case a target’s minor child was among those targeted with phishing. We believe this “off-center” targeting further indicates both the well-informed nature of the targeting, and an intelligence gathering objective.

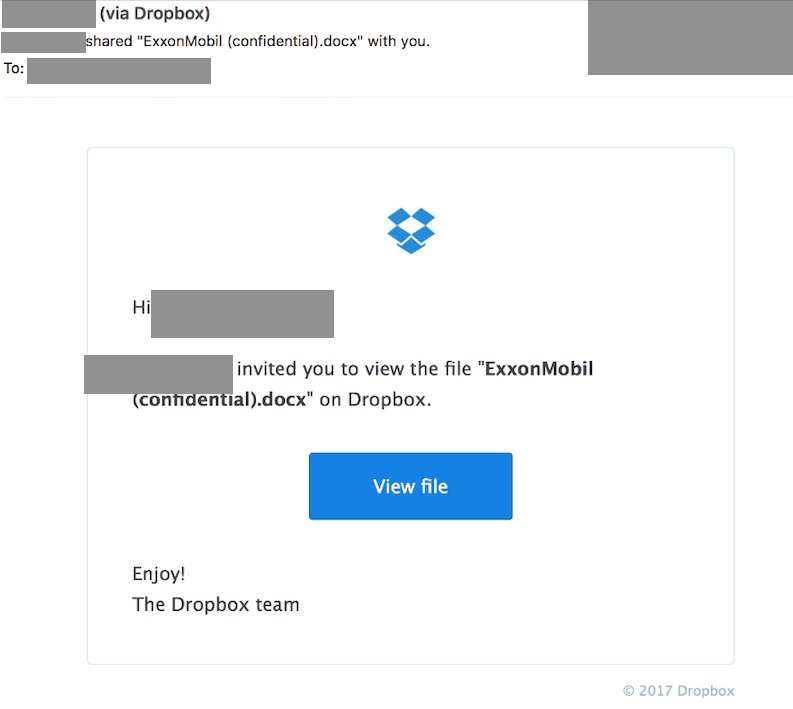

Much of the phishing against these individuals referenced targets’ work on ExxonMobil and climate change. Notably, multiple phishing messages seemed to reference unspecified confidential documents concerning ExxonMobil. A number of these messages impersonated individuals involved in the #ExxonKnew advocacy campaign or individuals involved in litigation against ExxonMobil, such as legal counsel.

Table 4: Examples of phishing messages referencing confidential information and notifications concerning ExxonMobil sent to individuals at advocacy organizations. The messages were sent from accounts masquerading as close colleagues of those targeted.

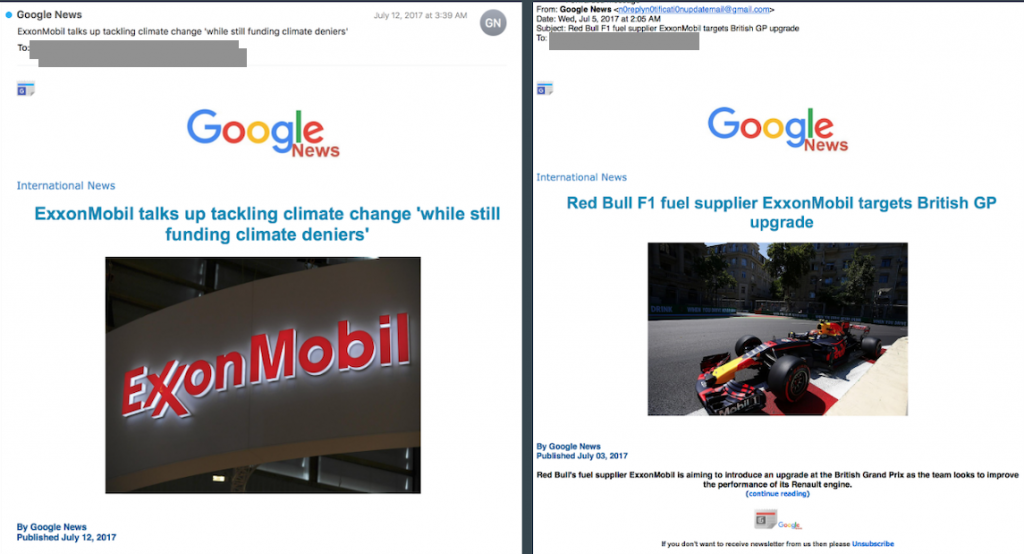

In other cases, Dark Basin sent fake Google News updates concerning ExxonMobil, clearly a topic of interest to the targets.

Other ruses included fake Twitter direct messages and other correspondence purporting to concern climate change advocacy. Dark Basin also regularly employed more generic phishing emails using the same infrastructure. We observed a similar mix of topic-specific and generic attempts by Dark Basin against targets in other clusters, such as targeted hedge funds. Dark Basin also regularly made use of third-party link tracking services in their messages.

Evidence of Compromise

In at least one case, Dark Basin repurposed a stolen internal email to re-target other individuals. This incident led us to conclude that Dark Basin had some success in gaining access to the email accounts of one or more advocacy groups.

Who Was the Client?

Dark Basin’s targeting revealed a highly detailed and accurate understanding of their targets and their relationships. Not only did phishing emails come from accounts masquerading as targets’ colleagues and friends, but the individuals that Dark Basin chose to target showed that it had a deep knowledge of informal organizational hierarchies (e.g., masquerading as individuals with greater authority than the target). Some of this knowledge would likely have been hard to obtain from an open source investigation alone. Combined with the bait content, which was regularly tailored to the #ExxonKnew campaign, we concluded that Dark Basin operators were likely provided with detailed instructions not only about whom to target, but what kinds of messages specific targets might be responsive to.

While our research concluded with high confidence that Dark Basin was responsible for transmitting these phishing attempts, we do not have strong evidence pointing to the party commissioning them and we are not conclusively attributing Dark Basin’s phishing campaign against these organizations to a particular Dark Basin client at this time. That said, the extensive targeting of American nonprofits exercising their first amendment rights is exceptionally troubling.

More US Civil Society Targets

At least two American advocacy groups were targeted by Dark Basin during a period in which they were engaged in sustained advocacy requesting that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) preserve net neutrality rules in the US. EFF published a report on this targeting in 2017, observing that US non-governmental organizations Fight for the Future and Free Press were targeted between July 7 and August 8, 2017. We also observed targeting of additional US civil society groups which will be discussed in future reporting.

US Media Outlets

In addition to the targeting of civil society, we found that journalists from multiple major US media outlets were also targeted. Targets included journalists investigating topics related to the advocacy organizations mentioned above, as well as multiple business reporters.

Industry Targets

Dark Basin’s targeting was widespread and implicated multiple industries. In the sample of the targeting collected by Citizen Lab, we found that the financial sector was the most targeted. The following section briefly outlines several industry verticals of particular interest.

Hedge Funds, Short Sellers, Financial Journalists

The most prominent targeting of the financial sector concerned a cluster of hedge funds, short sellers, journalists, and investigators working on topics related to market manipulation at German payment processor Wirecard AG . We note that the offices of Wirecard AG were searched on Friday, June 5 2020 by German police in connection with a criminal investigation against certain executive board members launched by Munich prosecutors.

After extensive work with targeted organizations and individuals surrounding the Wirecard AG case, we concluded the unifying thread behind this targeting was its aim at individuals who held short positions in Wirecard AG around the time of the targeting and financial reporters covering the Wirecard AG case. Some individuals were targeted almost daily for months, and continued to receive messages for years.

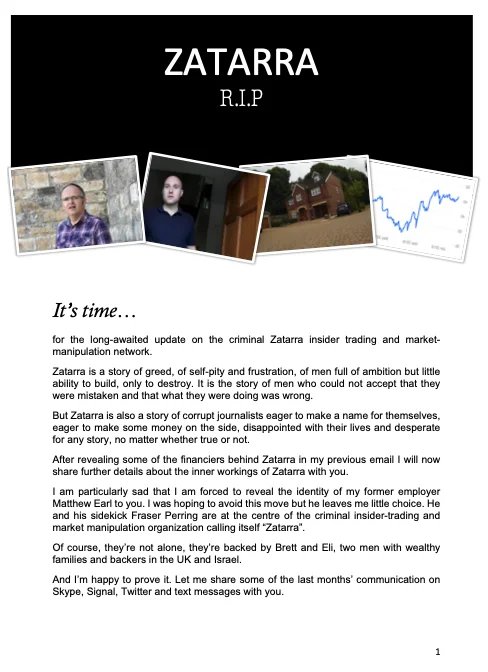

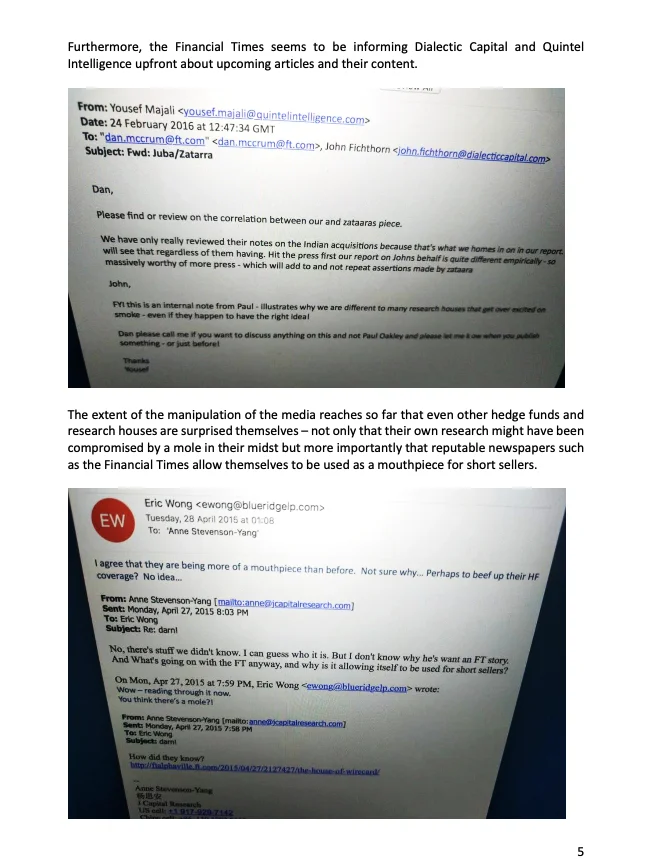

Private emails from multiple journalists, short sellers, and hedge funds were made public as part of a “leaks” website and campaign, which included a PDF circulated via online posts to various forums. The campaign took its name from Zatarra, then a company operated by several of the targets. As Table 5 shows, the document draws heavily on excerpts of correspondence between journalists and their sources. The targets have said that these emails were misleadingly presented and edited before being posted on the website. We believe that, while the documents may have been based on emails obtained by Dark Basin through phishing, a second entity may have undertaken the work of compiling and presenting these documents on the website, given the sophistication of the writing, use of investigative jargon, and techniques such as detailed organizational charts.

Table 5: Pages from the documents posted on the ‘Zatarra Leaks’ website.

As with the targeting of the organizations involved in the #ExxonKnew advocacy campaign, we are not conclusively attributing this campaign to a specific sponsor at this time.

Global Banking and Financial Services

Several international banks and investment firms, as well as prominent corporate law firms in the United States, Asia, and Europe, were targets. We also found a number of companies involved in offshore banking and finance were also targeted.

Legal Services

Lawyers were heavily represented in Dark Basin targeting. We found targeted individuals in many major US and global law firms. Lawyers working on corporate litigation and financial services were disproportionately represented, with targets in many countries including the US, UK, Israel, France, Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, Iceland, Kenya, and Nigeria.

The Energy Sector

We identified targets in multiple energy and extractive sectors, including petroleum companies. Targets ranged from lawyers and staff to CEOs and executives. In some cases, we observed large swaths of the energy and extractive industry targeted in a particular country, ranging from oilfield services companies and energy companies to prominent industry figures and officials at relevant government offices.

Eastern and Central Europe, Russia

We identified a range of targets in Eastern and Central Europe, and Russia, indicative of targeting surrounding the investments and actions of extremely wealthy individuals, including cases surrounding individuals who could be considered oligarchs.

Government

We identified targets in multiple governments, ranging from senior elected officials and their staff to members of the judiciary, prosecutors, members of parliament, and political parties. In a number of cases, we were able to connect this targeting to specific issues. We identified at least one individual who ran for elected office in the US. We anticipate providing future reporting on these cases.

Personal Disputes

Many of Dark Basin’s targets were high profile, well-resourced individuals. However, we also found that private individuals were also targeted, which appeared to correlate with divorces or other legal matters.

Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures

Over the course of our investigation, we found Dark Basin regularly adapting techniques, possibly in response to disruptions from email providers filtering their phishing attempts. What follows is a brief overview of these techniques.

Phishing Emails

Dark Basin sent phishing emails from a range of accounts, including Gmail accounts as well as self-hosted accounts. Sophistication of the bait content, specificity to the target, message volume, and persistence across time varied widely between clusters. It appears that Dark Basin’s customers may receive varying qualities of service and personal attention, possibly based on payment, or relationships with specific intermediaries.

URL Shorteners

The use of URL shorteners for masking phishing sites is a common technique. Over a sixteen month period, we enumerated 28 unique URL shortener services operated by Dark Basin.

The malicious URL shorteners used in this campaign typically ran an open source URL shortening software called Phurl. We analyzed the code and found that Phurl generated sequential shortcodes making it trivial for us to enumerate the URL shorteners. Figure 4 below shows numerous examples of the Phurl-based malicious shorteners we tracked.

Enumeration

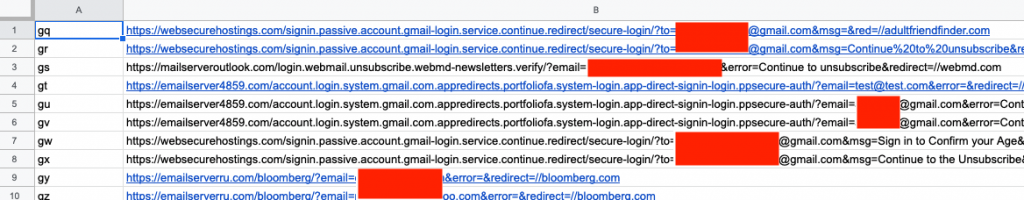

We tracked these 28 URL shorteners nearly continuously using a Python script. Overall, our enumeration of these shorteners uncovered 27,591 different long URLs, each of which led to a Dark Basin credential phishing website. This campaign operated at a scale we had not previously detected in our research into targeted intrusion operations (versus generic phishing operations). Often, the email address of the target was included in the URL.

Figure 5 shows a sample of the output from one shortener during a single collection period. The first column shows the specific “short code” for a shortener hosted on the domain anothershortnr[.]com and the second column shows the “long URL,” i.e., the actual destination website hosting the credential phishing pages. For example, a phishing email containing the shortened link http://anothershortnr[.]com/gu would, when clicked, direct the target to the destination URL:

https://emailserver4859[.]com/account.login.system.gmail.com.appredirects.portfoliofa.system-login.app-direct-signin-login.ppsecure-auth/?email=REDACTED@gmail.com&error=Continue to unsubscribe&redirect=//google.comThe domain, emailserver4859[.]com, was set up by attackers to host a credential phishing page designed to gather account credentials from webmail providers, including Gmail.

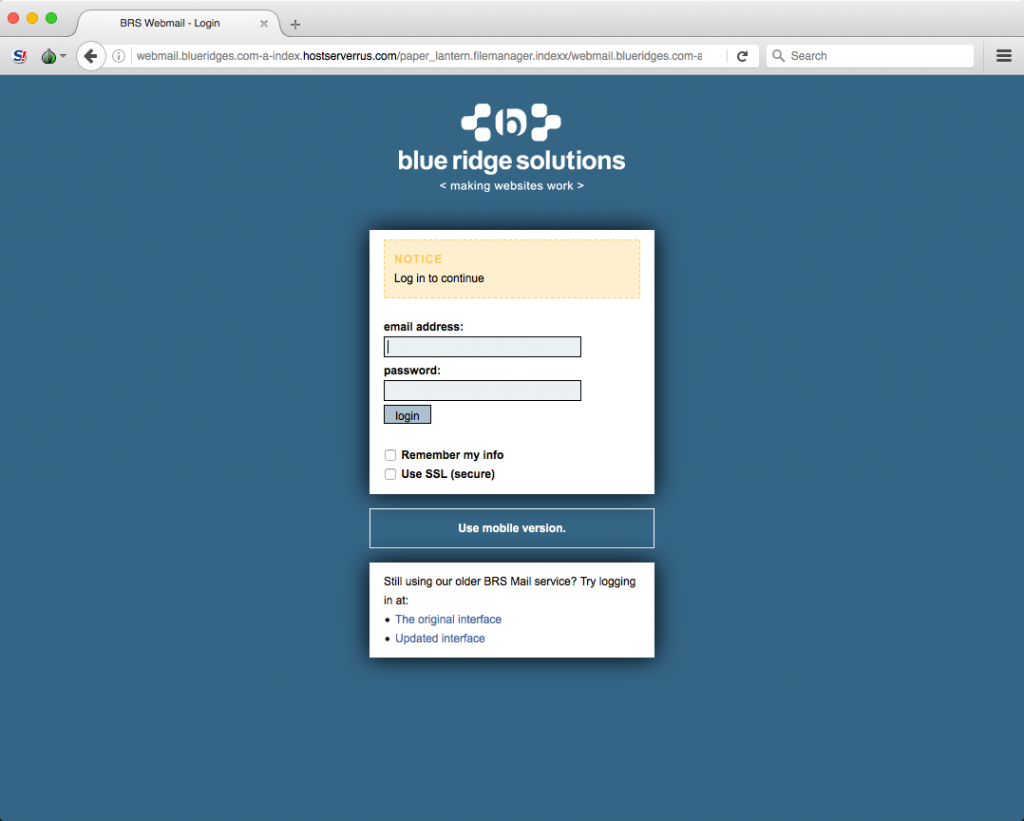

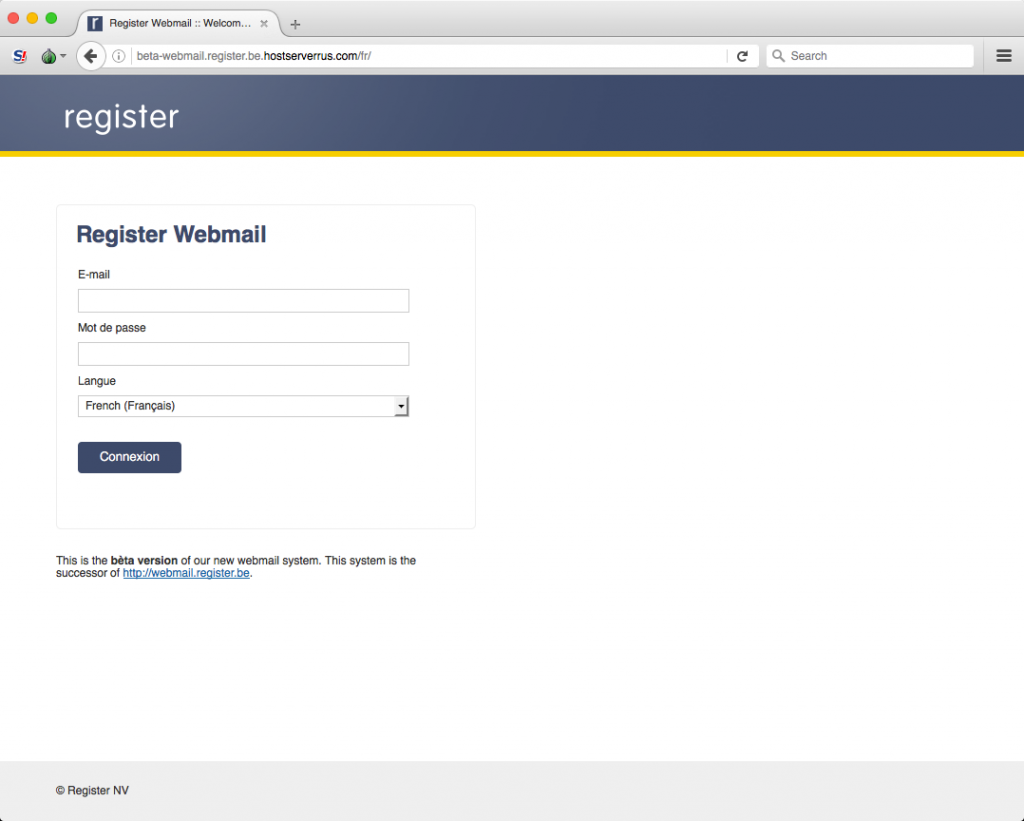

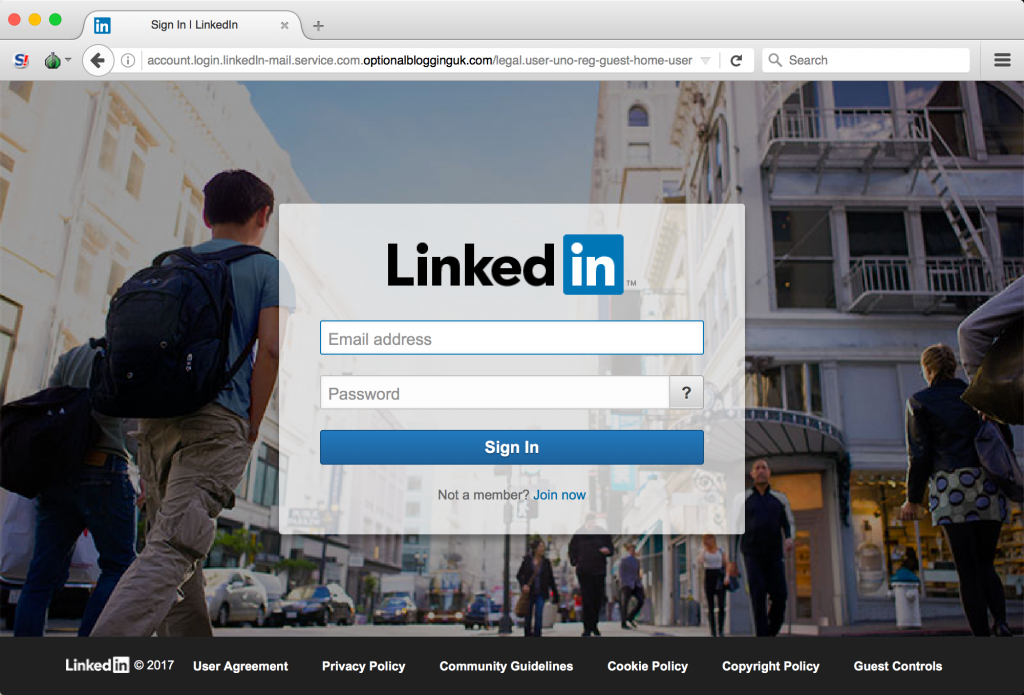

Credential Phishing Websites

The malicious links we discovered during our tracking each led to credential phishing sites, i.e., websites designed to look identical to popular online web services such as Google Mail, Yahoo Mail, Facebook, and others. In addition, Dark Basin operators had created phishing websites which copied the look and feel of specific web services used or operated by the target or their organization (Figure 11).

Table 6: Images of several phishing sites deployed in the observed campaigns.

Phishing Kit

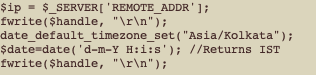

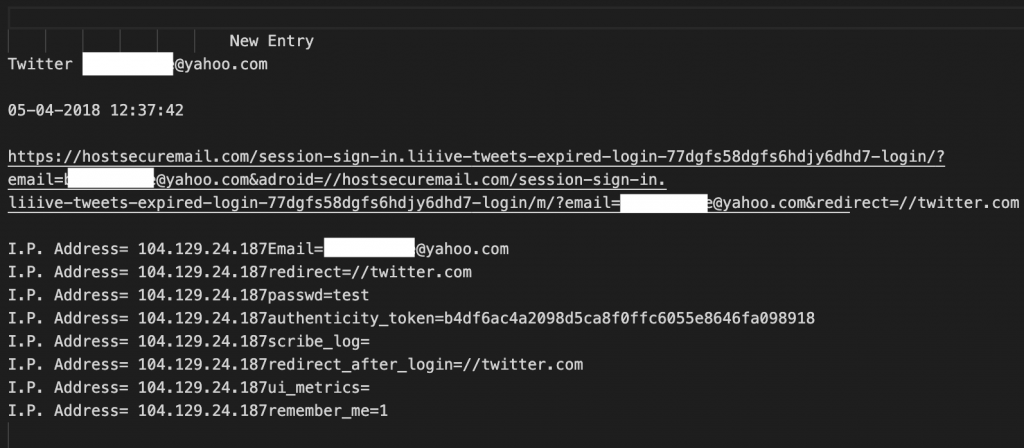

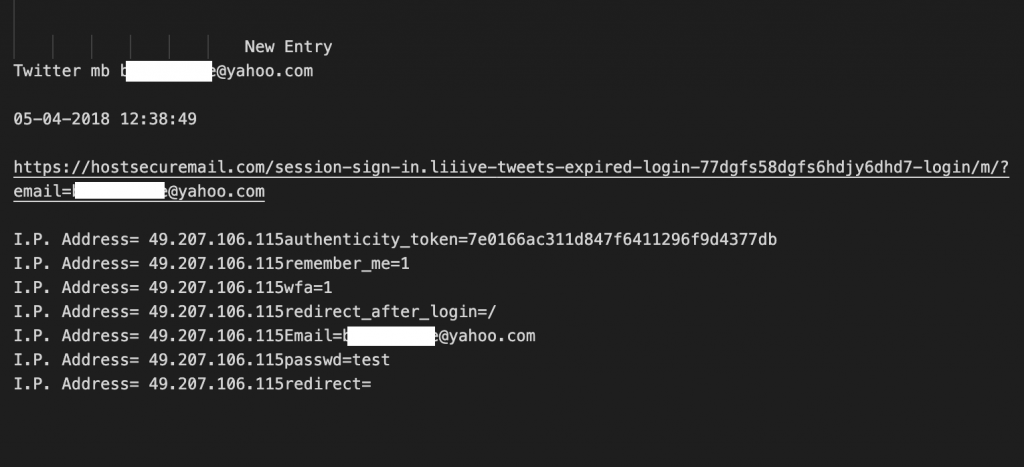

In several cases, Dark Basin left the source code of their phishing kit openly accessible. The source code included references to log files, which were also publicly accessible. The log files recorded every interaction with the credential phishing website, including testing activity carried out by Dark Basin operators.

The source code also contained several scripts that processed details including usernames and passwords entered by victims, as well as the victims’ IP address. These details were both emailed to a Gmail address controlled by Dark Basin and recorded in one or more log files on the web server itself. Several of the scripts recorded these details with a timestamp in India’s UTC+5:30 (IST) timezone (Figure 6).

Testing the Phish

In reviewing log files left openly available on several of the active phishing servers, we observed Dark Basin operators testing their phishing links and credential theft kits.

We observed numerous occurrences where both real target email addresses and obviously fake email addresses were entered into the phishing pages using the password ‘test’, ostensibly to simulate or test the functionality of the phishing page. The IP addresses which were logged by the phishing kit for these test entries were typically from anonymizing VPN services, but sometimes the logs showed that the test had been conducted using an IP address associated with an Indian broadband provider. Figures 7 and 8 show log excerpts from a pair of tests found in the log files from hostsecuremail[.]com, a Dark Basin credential phishing site:

Success Rates

It is clear that Dark Basin operators were successful with at least some of their phishing campaigns. In cases observed by targets, Dark Basin was observed using commodity VPNs to access accounts using stolen credentials. We also found that logs from some phishing kits were publicly accessible. After reviewing these logs and working with targets, we concluded that Dark Basin’s deceptions, while individually not always effective, did achieve some account access in part because the group could be extremely persistent. For example, we found that some “high value” targets were sent more than one hundred phishing attempts with very diverse content. Some failure to recognize attempted phishing is to be expected when an entire organization or network of individuals working together on a shared advocacy goal is targeted by such a persistent adversary.

Dark Basin’s reliance on a rarely seen URL shortener software, continued reuse of the same registration identities and hosting providers for their infrastructure, and the uniqueness of their phishing kit all contributed to our ability to track them continuously during these campaigns. Perhaps most important however was the additional visibility provided by working closely with the targeted individuals and organizations. This view into the persistent attempts to compromise the targets greatly amplified our ability to follow breadcrumbs left by Dark Basin operators.

Mercenary Intrusion: A Global Problem

Dark Basin’s thousands of targets illustrate that hack-for-hire is a serious problem for all sectors of society, from politics, advocacy and government to global commerce.

Many of Dark Basin’s targets have a strong but unconfirmed sense that the targeting is linked to a dispute or conflict with a particular party whom they know. However, absent a systematic investigation, it is difficult for most individuals to determine with certainty who undertakes these phishing campaigns and/or who may be contracting for such services, especially given that Dark Basin’s employees or executives are unlikely to be within the jurisdiction of their local law enforcement. Further, while many of the targets whom we contacted had a sense they were being phished in a targeted operation, many others did not share this awareness. These targets either concluded that they were being phished for an unknown reason, or simply did not notice the targeting against the background of unrelated phishing messages and spam.

We believe there is an important role for major online platforms who have the capacity to track and monitor groups like Dark Basin. We hope Google and others will continue to track and report such hack-for-hire operations. We also encourage online platforms to be proactive in notifying users that have been targeted by such groups, such as providing detailed warnings beyond generic notifications to help enable targets to recognize the seriousness of the threat and take appropriate action.

Hacking for hire

Dark Basin’s activities make it clear that there is a large and likely growing hack-for-hire industry. Hack-for-hire groups enable companies to outsource activities like those described in this report, which muddies the waters and can hamper legal investigations. Previous court cases indicate that similar operations to BellTroX have contracted through a murky set of contractual, payment, and information sharing layers that may include law firms and private investigators and which allow clients a degree of deniability and distance.

The growth of a hack-for-hire industry may be fueled by the increasing normalization of other forms of commercialized cyber offensive activity, from digital surveillance to “hacking back,” whether marketed to private individuals, governments or the private sector. Further, the growth of private intelligence firms, and the ubiquity of technology, may also be fueling an increasing demand for the types of services offered by BellTroX. At the same time, the growth of the private investigations industry may be contributing to making such cyber services more widely available and perceived as acceptable.

A clear danger to democracy

The rise of large-scale, commercialized hacking threatens civil society. As this report shows, it can be used as a tool of the powerful to target organizations that may not have sophisticated cybersecurity resources and consequently are vulnerable to such attacks.

For example, in a four-year-study, we concluded that digital threats undermined civil society organizations’ core communications and missions in a significant way, sometimes as a nuisance or resource drain, or more seriously as a major risk to individual safety. Citizen Lab has also previously researched and documented the harms of phishing campaigns against civil society around the globe.

We believe it is especially urgent that all parties involved in these phishing campaigns are held fully accountable. For this reason, and on the request of multiple targets of Dark Basin, Citizen Lab provided indicators and other materials to the US DOJ.

Acknowledgements

We thank the many targets that have helped us during the past three years. Without your diligence and effort this investigation would not have been possible. We have special gratitude for the journalists and media outlets for their patience.

We also personally thank several targets in particular for incredible efforts to help us identify malicious messages and investigate this case: Matthew Earl of ShadowFall, Kert Davies of the Climate Investigations Center, and Lee Wasserman of the Rockefeller Family Fund.

We thank our colleagues at NortonLifeLock for their hard work. The sheer scale of activities like Dark Basin makes collaboration essential.

We thank those that have requested to not be named, including TNG. You know who you are, and your hard work inspires us.

Special thanks to Citizen Lab colleagues, especially Adam Senft, Miles Kenyon, Mari Zhou, and Masashi Crete-Nishihata.

Many thanks to Peter Tanchak.

Thanks to The Electronic Frontier Foundation, especially Eva Galperin and Cooper Quintin.

Updated to reflect that Citizen Lab research, including the research featured in this report, is supported by multiple philanthropies. Click here to learn more.

Appendix A: Links to BellTroX

The appendix lists various additional links to BellTroX including social media postings and domain registrations.

Social Media Post

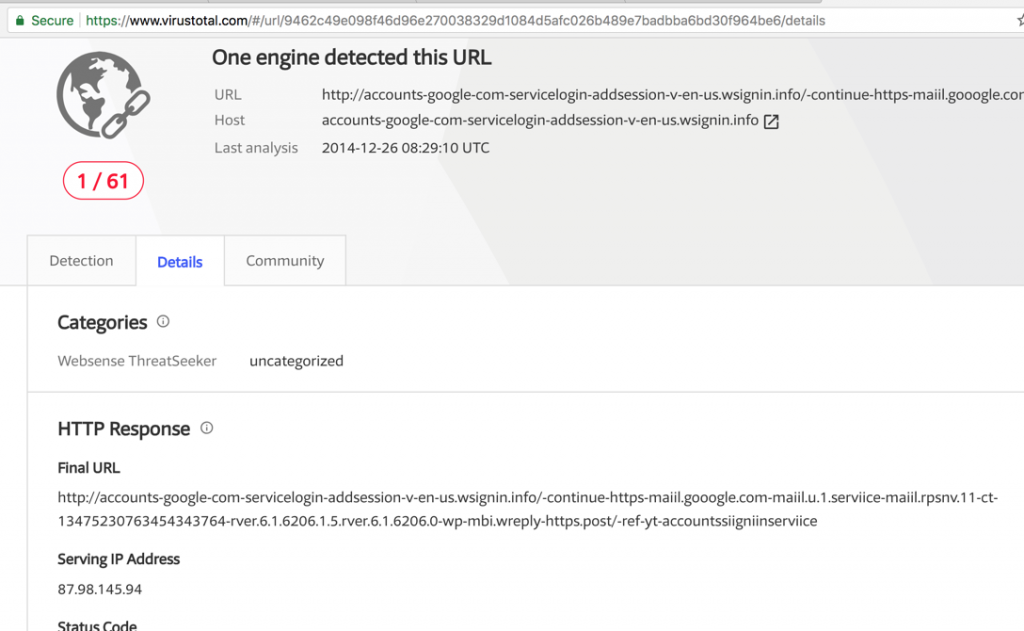

One of the domains we had observed Dark Basin using as a URL shortener was pushthisurl[.]com. A submission to VirusTotal from December 2016 contains an important clue towards attribution. The URL submitted to VirusTotal appeared to be very similar to phishing URLs deployed by Dark Basin:

https://account.facebook.com.supportserviceonline[.]com/profile.php.id=100006944714691&fref=hovercard.100006944714691&lst=1000095728519043A1000069447146913A14/paterns/?adroid=http://pushthisurl.com/jb&msg=Sign%20in%20to%20continue&red=//facebook.com/messaged/updates.zxkjcvhzkxcv9xcvzj76/Notify-iThe highlighted section in this URL shows a parameter called adroid that contains a URL, http://pushthisurl[.]com/jb. In examining the collection of phishing links and the phishing kit used by Dark Basin, we found that the adroid parameter was used to redirect mobile visitors to a mobile-optimized phishing page.

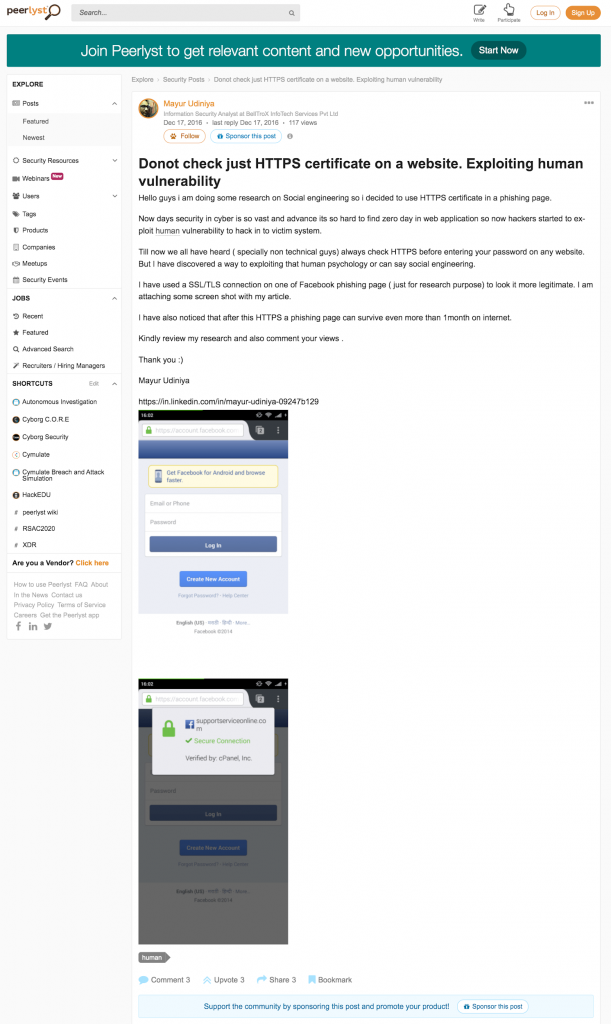

This URL suggests Dark Basin had been active earlier than we had observed. More importantly, the domain in this URL, account.facebook.com.supportserviceonline[.]com also appeared in a now deleted post on the Information Security forum website Peerlyst.

In a screenshot of this post (Figure 10), a user who identifies himself as an employee of BellTroX InfoTech Services explains a technique for creating a phishing page posing as a Facebook login screen. The poster provides two screenshots, one of which displays the domain name account.facebook.com.supportserviceonline[.]com.

Notably, this precise technique of using a subdomain which appears similar to a legitimate web service domain was used in virtually all of the 27,591 phishing links we discovered in our tracking of Dark Basin activity.

Domain Registrations

During our research into the various infrastructure components of the Dark Basin activity, we noticed a unique recurring pattern in many of the credential phishing URLs. Several examples are provided below, highlighted to show the pattern of interest:

http://login.reg.service-microsoftonline.hostname-mail-i.optionsothego[.]com/continue-http-rnd-maiiil.com-maiil.u.1.serviice-maiil.rpsnv.11-ct-13475230763454343764-rver.6.1.6206.1.5.rver.6.1.6206.0-wp-mbi.wreply-https/mb/?to=REDACTED&msg=Sign%20in%20to%20continue%20to%20OneDrive&red=//login.live.com/help

http://login.service-microsoftonline.reg.hostname-mail-id.fastserverusa[.]com/continue-http-rnd-maiiil.com-maiil.u.1.serviice-maiil.rpsnv.11-ct-13475230763454343764-rver.6.1.6206.1.5.rver.6.1.6206.0-wp-mbi.wreply-https?to=REDACTED&msg=Sign in to confirm your age&red=//youporn.com&adroid=

http://login-microsoftonline.auditionregistrationonline[.]com/continue-http-rnd-maiiil.com-maiil.u.1.serviice-maiil.rpsnv.11-ct-13475230763454343764-rver.6.1.6206.1.5.rver.6.1.6206.0-wp-mbi.wreply-https?to=REDACTED&msg=&red=//youtube.com/watch?v=2WRFwTChdMk&adroid=//

We found a VirusTotal submission of a URL hosted on the domain wsignin[.]info which contained this same string:

Appendix B: Indicators of Compromise

Citizen Lab and NortonLifeLock are jointly releasing this list of Indicators of Compromise.

Endnotes

(1) Figure updated to reflect that on January 9th 2018 the NYC filed suit against Exxon et. al, not the NY AG.

(2) Sentence updated to reflect that in January 2018, NYC filed suit against Exxon et al., not the NY AG.