Triple Threat

NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware Returns in 2022 with a Trio of iOS 15 and iOS 16 Zero-Click Exploit Chains

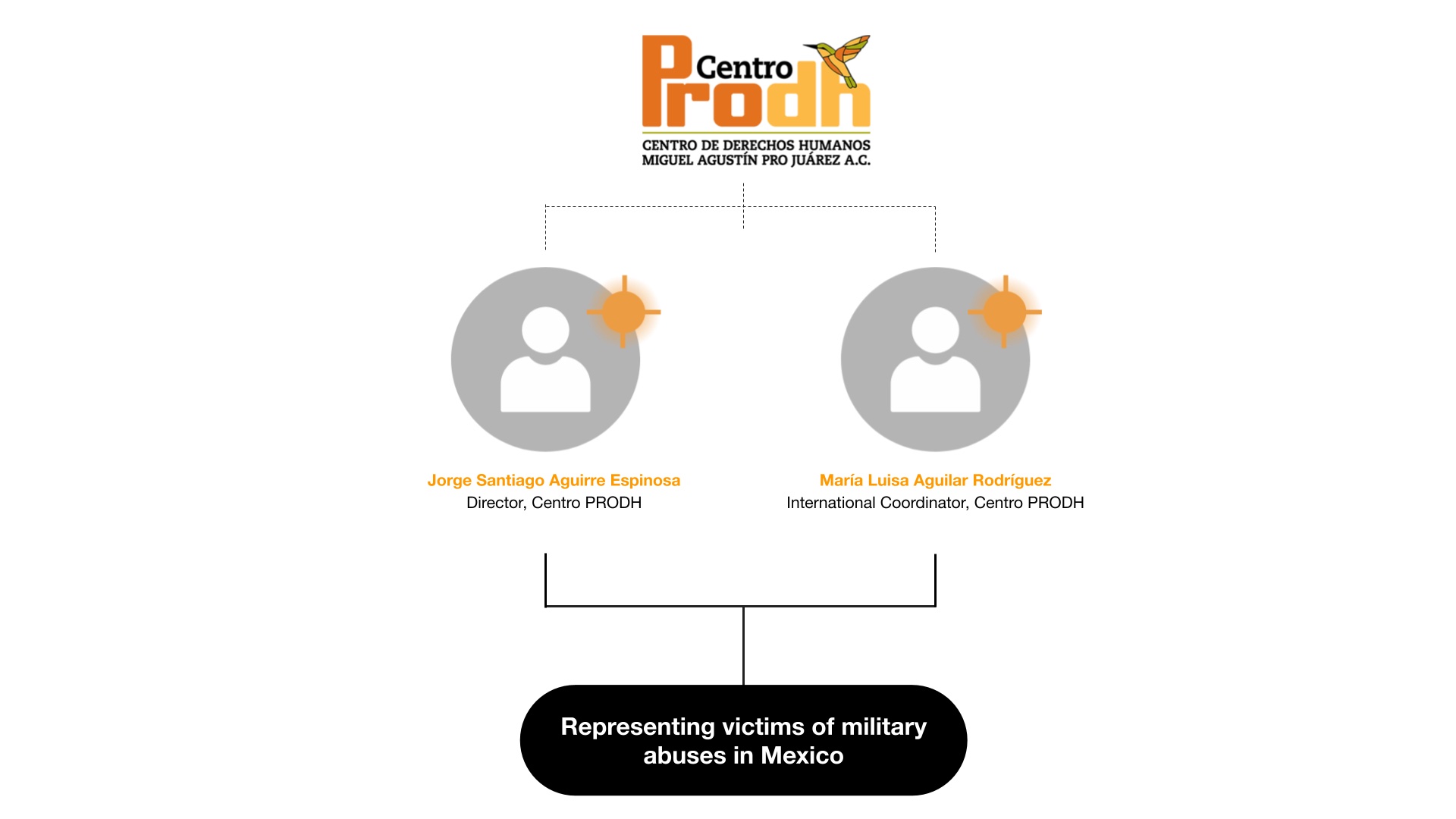

In 2022, the Citizen Lab gained extensive forensic visibility into new NSO Group exploit activity after finding infections among members of Mexico’s civil society, including two human rights defenders from Centro PRODH, which represents victims of military abuses in Mexico.

Key Findings

- In 2022, the Citizen Lab gained extensive forensic visibility into new NSO Group exploit activity after finding infections among members of Mexico’s civil society, including two human rights defenders from Centro PRODH, which represents victims of military abuses in Mexico.

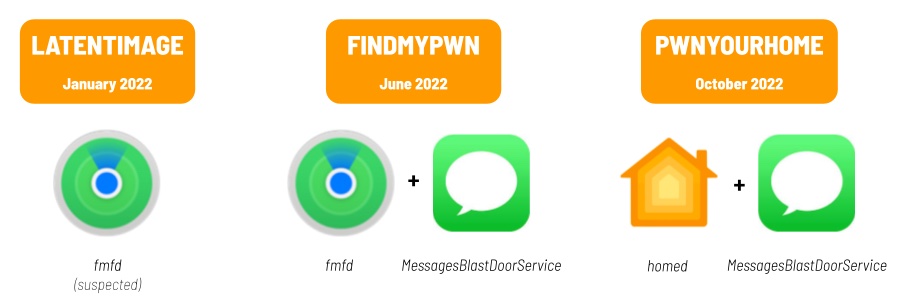

- Our ensuing investigation led us to conclude that, in 2022, NSO Group customers widely deployed at least three iOS 15 and iOS 16 zero-click exploit chains against civil society targets around the world.

- NSO Group’s third and final known 2022 iOS zero-click, which we call “PWNYOURHOME,” was deployed against iOS 15 and iOS 16 starting in October 2022. It appears to be a novel two-step zero-click exploit, with each step targeting a different process on the iPhone. The first step targets HomeKit, and the second step targets iMessage.

- NSO Group’s second 2022 zero-click (“FINDMYPWN”) was deployed against iOS 15 beginning in June 2022. It also appears to be a two-step exploit; the first step targets the iPhone’s Find My feature, and the second step targets iMessage.

- We shared forensic artifacts with Apple in October 2022, and additional forensic artifacts regarding PWNYOURHOME in January 2023, leading Apple to release several security improvements to HomeKit in iOS 16.3.1

- Once we had identified FINDMYPWN and PWNYOURHOME, we discovered traces of NSO Group’s first 2022 zero-click (“LATENTIMAGE”) on a single target’s phone. This exploit may also have involved the iPhone’s Find My feature, but is a different exploit chain than FINDMYPWN.

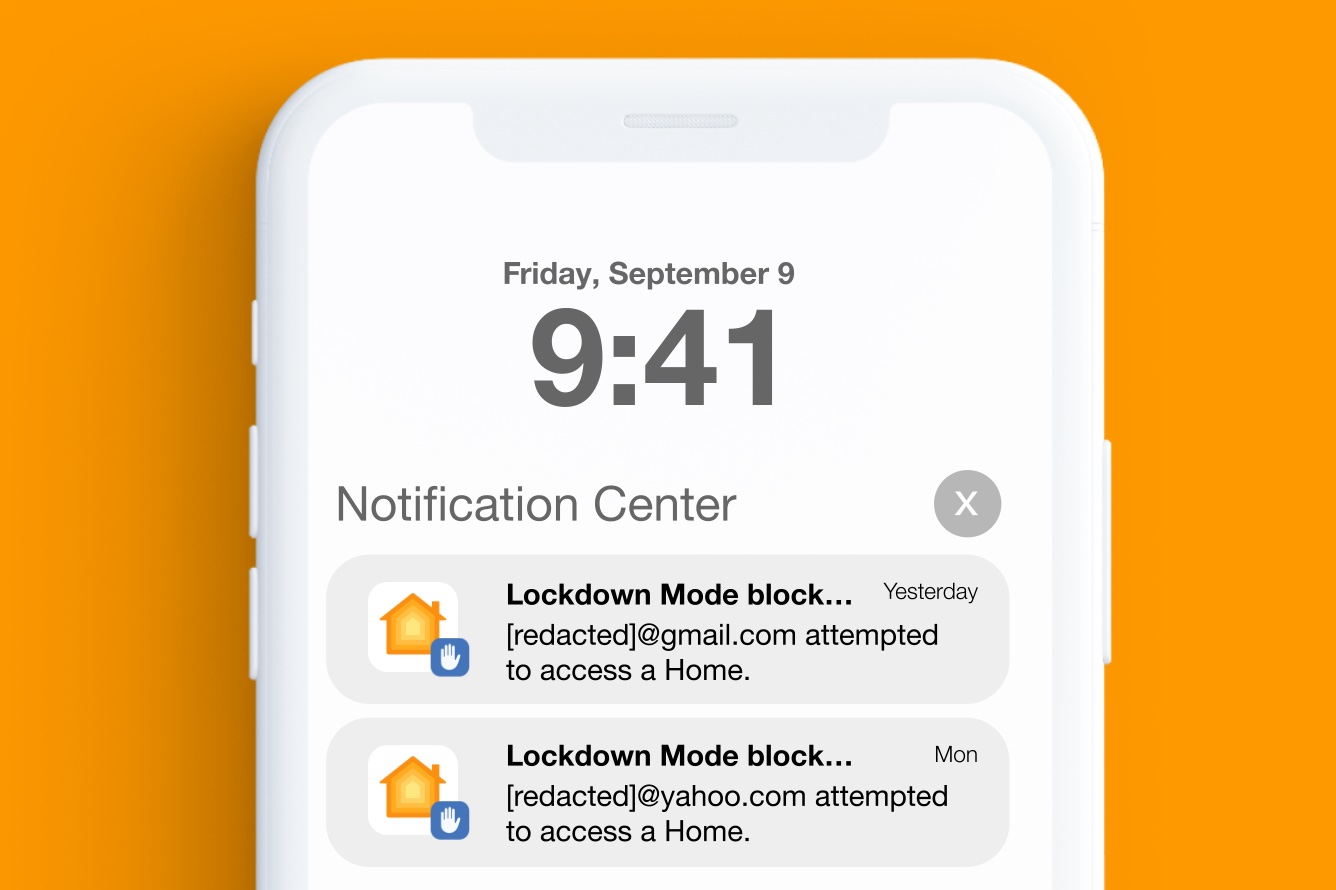

- For a brief period, targets that had enabled iOS 16’s Lockdown Mode feature received real-time warnings when PWNYOURHOME exploitation was attempted against their devices. Although NSO Group may have later devised a workaround for this real-time warning, we have not seen PWNYOURHOME successfully used against any devices on which Lockdown Mode is enabled.

1. Targeting in Mexico

The Citizen Lab first gained forensic visibility into NSO Group’s 2022 zero-click exploits in October 2022 in the course of a joint investigation with Mexican NGO Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales (R3D). After examining several devices belonging to members of Mexican civil society, we discovered FINDMYPWN, which helped us subsequently discover PWNYOURHOME and LATENTIMAGE within a broader target population (including outside Mexico). Two Mexican civil society targets consented to be named in this report.

Extrajudicial Killings and Forced Disappearances

Mexico’s government and military have a long history of grave human rights abuses, extrajudicial killings, and disappearances. From the 1960s through the 1980s, Mexico experienced the so-called “Dirty War” (“Guerra Sucia”), a conflict between the government ruled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), guerrilla groups, and left-wing student movements. Between 1968 and 1982, an estimated 1,200 individuals were disappeared.

In 2022, the United Nations Committee on Enforced Disappearances and the Working Group on Enforced and Voluntary Disappearances noted that there were now more than 100,000 officially registered disappearances in Mexico.

One widely publicized case of disappearances relevant to this case of spyware infection occurred in September 2015 when a group of 43 students at a teacher training college were forcibly disappeared after traveling to Iguala to protest teacher hiring practices. Their subsequent disappearance is referred to as the “Iguala mass kidnapping,” or simply the “Ayotzinapa case.” In 2017, we reported that three members of the Mexican legal aid and human rights organization, Centro PRODH, were targeted with Pegasus spyware, along with investigators involved in the Ayotzinapa case. At the time of targeting, which was in 2016, Centro PRODH was representing families of the disappeared students.

2022 Targets: Human Rights Defenders

Our research collaboration with R3D led to the identification of two human rights defenders working at Centro PRODH whose devices were infected with Pegasus spyware. Both targets consented to participate in a research study with the Citizen Lab and to be named in this report. The timing of the infections on their devices corresponds to events of importance to the activities of Centro PRODH, and suggests that the Pegasus operator may have been seeking to penetrate and perhaps blunt the impact of Centro PRODH’s work relating to human rights violations committed by the Mexican Army.

One infected device belongs to Jorge Santiago Aguirre Espinosa, the Director of Centro PRODH. Mr. Aguirre was previously identified as one of the Centro PRODH Pegasus targets by Citizen Lab in 2017, which found evidence of Pegasus infection attempts via text message on his device that he had been sent in 2016. In 2022, he was infected at least twice via the FINDMYPWN exploit. The spyware was active on his device on June 22, 2022 and July 13, 2022.

On June 22, 2022, the same date as the first infection of Mr. Aguirre’s phone, Mexico’s truth commission investigating the Dirty War launched its activities in a ceremony at a Mexican military camp where many of the abuses had taken place. Victims of human rights violations participated in the ceremony, including Alicia de los Ríos, who is represented by Centro PRODH. She is currently appealing to national and international bodies to seek justice for the disappearance of her mother at the hands of the Mexican army.

A second Centro PRODH staffer was infected the day after the ceremony. María Luisa Aguilar Rodríguez, International Coordinator at Centro PRODH, was infected on June 23, 2022. Her work includes representing victims of human rights violations perpetrated by the Mexican army, including the Ayotzinapa case. She was subsequently infected twice more via the FINDMYPWN exploit. The spyware was active on her device on September 24, 2022 and September 29, 2022.

The September 2022 Pegasus attacks coincided with several events in the Ayotzinapa case, in which Centro PRODH represents the families of the disappeared. This includes the publication of a report by an international group of experts that questioned the authenticity of evidence published by the government, denounced the Mexican Army for refusing to surrender key documents for the case, and called out governmental interference in the investigation.

The attacks also coincide with the cancellation of several arrest warrants against military personnel involved in the Ayotzinapa case after pushback from the Mexican Army, and the resignation of the Special Prosecutor for the case who denounced interference by Mexico’s General Prosecutor in his investigation.

2. NSO Group Zero-Clicks Released in 2022

In 2022, while examining cases of suspected infections in Mexico, including the two cases named in this report, we found matches with four Pegasus indicators that we had seen in previous infections between August and December 2021 using both FORCEDENTRY and one-click attacks. Further analysis yielded additional indicators, which were then applied to analyze additional devices in the global pool of 2022 Pegasus victims to uncover more details about NSO Group’s 2022 exploits.

These indicator overlaps allow us to attribute the 2022 zero-click chains to NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware with high confidence. Overall, we believe NSO Group deployed at least three zero-click chains in 2022 (Figure 2), exploiting a variety of apps and features on the iPhone. We have observed cases of some of the chains deployed as zero-days against iOS versions 15.5 and 15.6 (FINDMYPWN), and 16.0.3 (PWNYOURHOME).

To protect our continued ability to identify Pegasus infections, we are not releasing further details about these Pegasus indicators at this time as we continue to observe what we interpret to be concerted efforts by NSO Group to evade detection by the methods deployed by researchers. For example, in contrast to previous versions of Pegasus, the versions deployed in 2022 appear to more thoroughly remove data from various iPhone log files, in an apparent attempt to thwart researchers from understanding the nature of the vulnerabilities exploited to compromise phones, and to evade detection.

We shared our observations of these exploit chains with Apple in October 2022 and in January 2023. Targets we found in the 2022 target pool reported receiving notifications from Apple in November and December 2022, and March 2023.

In the next sections, we review the three exploit chains in reverse chronological order.

3. PWNYOURHOME: An iOS 15 and iOS 16 Zero-Click Exploit

The PWNYOURHOME exploit appears to be a novel two-phase zero-click exploit, with each of the two phases targeting a different process on the phone. The first phase of the exploit involves the HomeKit functionality built into iPhones (via the homed process), and the second phase of the exploit involves iMessage (via the MessagesBlastDoorService process). PWNYOURHOME appears to succeed against a target even if the target has never configured a “Home” inside HomeKit. However, in some cases, the email address of the PWNYOURHOME attacker is logged and Pegasus fails to delete this email from the HomeKit database.

We obtained logs from multiple devices compromised with PWNYOURHOME. In one case, the attacker’s email address ([REDACTED]@gmail.com) was logged. The phone logs showed that the [REDACTED]@gmail.com email address was added to HomeKit approximately eight minutes before the Pegasus spyware was recorded running on the phone, and an iMessage attachment was deleted.

Phase One: HomeKit Daemon Crashes

Logs from another PWNYOURHOME-exploited device from the 2022 global target pool examined in the course of this investigation showed the homed process decoding what appears to be an unusual NSKeyedUnArchiver when it crashed. Logs showed that the NSKeyedUnArchiver decoding had been kicked off by the following function:

-[HMDHomeManager _handleHomeDataSync:] (in HomeKitDaemonLegacy)

The NSKeyedUnArchiver decoder invoked the decoder for NSDictionary, which in turn invoked the decoder for an implausible class not normally used within HomeKit. Issues with NSKeyedUnArchiver deserialization have been used in past iOS zero-click exploits targeting iMessage, so we redact the specific class to avoid assisting attackers. We disclosed this issue to Apple, who made several changes to HomeKit in iOS 16.3.1, including adding a new method, -[HMDHomeManager _shouldDecodeMessage:error:], which declines to decode certain HomeKit messages unless they arrive from a plausible source. This check guards the HomeKit code path we saw exploited.

Phase Two: BlastDoor Crashes

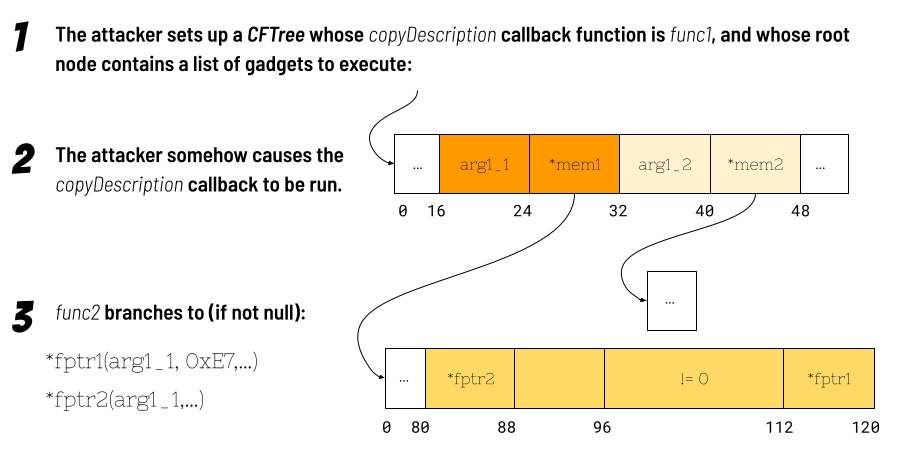

Logs from yet another PWNYOURHOME-exploited device from the 2022 target pool show that, following the homed phase of PWNYOURHOME, the phone downloaded PNG images from iMessage. Processing these images caused crashes in the MessagesBlastDoorService process. These crashes give us glimpses of what the exploit was doing at various stages, and suggest that the exploit may have circumvented pointer authentication codes (PAC) in some cases by repurposing PAC-valid pointers already present in memory, such as signed pointers to callback functions present in constant structs.

This is a well-known technique to circumvent PAC, and a mitigation exists in the form of contexts, which include an additional salt value in the PAC to thwart repurposing of signed pointers. However, in practice, the context is often set to zero, as it may be nontrivial for the compiler to automatically retrofit existing legacy code with a suitable context.

When MessagesBlastDoorService crashed, it appeared to be processing (via ImageIO) Apple MakerNote metadata included in a PNG image file. We have reconstructed a vignette of the exploit’s activity that seems to illustrate some gadgets it employs, though we have not yet fully identified the vulnerabilities exploited.

A CFTree‘s CopyDescription Method is Called

While deallocating various data structures as part of the _CGImageMetadataFinalize function, a series of events transpired, causing the CFCopyDescription method to be called on a CFTree object. Somehow, the attackers had set this CFTree‘s copyDescription callback function to be an unrelated function, “func1” (a name we assigned to the function in lieu of its real name, in order to avoid assisting attackers), in another framework within the iOS shared cache.

The copyDescription callback is invoked using the blraaz instruction, which validates the pointer’s PAC using a zero context. Because a pointer to func1 exists in a constant struct within the shared cache, a PAC-valid pointer with zero context is automatically generated at a known offset in the shared cache after relocation, when the library is loaded.

A Gadget is Invoked

The func1 function calls another function, “func2” (also a name we assigned in order to avoid assisting attackers), in a loop that appears intended to execute five times, followed by a sixth, final call.

The func2 function can be thought of as an “execute function with first argument” gadget. Within the func2 function, there are two possible locations where branches can be made (via blraaz). The first location sets the first function argument (register x0) to a value read from memory, and the second argument (register x1) to a fixed constant of 0xE7. The second call sets the first argument in the same way, but does not set register x1. The first call (and clobbering of x1) can be avoided if the pointer to the first function is null. The second call can be avoided if the first function returns an integer not equal to one.

Because the attacker (presumably) controls the data in the CFTree, and because the CFTree‘s copyDescription callback gets a pointer to the CFTree‘s root node, the attacker can craft the contents of the node to line up a series of additional gadgets (and first arguments) to be executed, provided that PAC-valid (with context of zero) pointers to these gadgets are available.

The exploit could execute arbitrarily many gadgets by recursively invoking func1, though we cannot say for sure if the exploit does this or not. The loop will be broken if func2 takes the second call and the second call returns a value greater than 3.

Another function, func3, whose signed pointer is present in the same struct as the signed pointer to func1, appears to be a loop around an “execute function with first two arguments” gadget.

A Possible Memory Copy Gadget

We were not able to identify the full library of gadgets used by this exploit, but we did notice that a particular memory copy gadget caused a segfault in the crash we observed. This memory copy gadget, which takes two arguments, dereferences the first argument, and stores a 64-bit value comprising the bottom 32-bits of the value read (setting the top 32-bits to zero) at the location pointed to by the second argument. Since the memory offsets for the ldr and str instructions do not need to be doubleword aligned, with manipulation of x1 (via a separate gadget), this gadget could be chained together to copy chunks of memory of arbitrary size, with the caveat that a single zero word is copied to the end of the destination.

The crash showed that the first call within func2 had been made, thus supplying 0xE7 for the memory copy gadget’s second argument. Because 0xE7 is not a valid memory address, the gadget caused MessagesBlastDoorService to crash. We redact specific details of the memory copy gadget to avoid assisting attackers, but we note that a pointer to this memory copy gadget is located within a constant struct within a library in the shared cache, thus ensuring availability of a signed pointer to attackers who are able to read known offsets within the shared cache.

We are presently unsure how PWNYOURHOME escapes the BlastDoor sandbox. However, the exploit ultimately launches Pegasus via mediaserverd.

Lockdown Mode Highlights Attack

Apple’s Lockdown Mode feature makes signs of an attempted PWNYOURHOME attack visible to the phone’s user by displaying notifications (Figure 4). We have seen no recent notifications on Lockdown Mode, nor have we seen any evidence of successful PWNYOURHOME compromise on Lockdown Mode. Given that we have seen no indications that NSO has stopped deploying PWNYOURHOME, this suggests that NSO may have figured out a way to correct the notification issue, such as by fingerprinting Lockdown Mode.

Additionally, we have not seen any cases of exploitation of iOS versions 16.1 and greater, suggesting that PWNYOURHOME may have been fixed or mitigated around this time.

4. FINDMYPWN: An iOS 15 Zero-Day, Zero-Click Exploit

We also identified an earlier exploit, FINDMYPWN, deployed against iOS 15 as a zero-day, zero-click exploit. We believe that, like PWNYOURHOME, FINDMYPWN is also a two-phase exploit.

In FINDMYPWN, exploitation appears to begin with the fmfd process exiting and relaunching. The fmfd process is associated with the iPhone’s built-in Find My functionality. We were unable to determine the reason for fmfd exiting and relaunching. In several cases we observed, FINDMYPWN apparently caused an item (which we suspect is the unacceptedShares folder) to be written and then deleted inside a cache directory related to the Find My app.

After fmfd exits and relaunches, phone logs indicate that MessageBlastDoorService is launched or relaunched, indicating that the phone was likely processing items received via iMessage.

We did not obtain sufficient crash logs from FINDMYPWN victims to identify whether the MessagesBlastDoorService activity was related to the PWNYOURHOME crashes, though we suspect that it is, as FINDMYPWN launches the Pegasus spyware via mediaserverd, just like PWNYOURHOME.

5. LATENTIMAGE: Traces of an Earlier Zero-Click Come to Light

After we had characterized PWNYOURHOME and FINDMYPWN, we re-checked our forensic analysis for earlier cases, and found a case of a third, distinct iOS 15 zero-click exploit deployed in January 2022. We call the exploit LATENTIMAGE because it appears to leave very few traces on the device.

The LATENTIMAGE exploit could also involve the iPhone’s Find My feature, as fmfd exited and re-loaded during exploitation, though we were unable to determine if it was the initial vector.

In contrast to FINDMYPWN and PWNYOURHOME, the LATENTIMAGE exploit launches the Pegasus spyware via springboard, indicating a different exploit chain. We identified a single case of LATENTIMAGE used against a target on 17 January 2022, using iOS version 15.1.1, which was out-of-date at the time.

6. Conclusion

NSO Group’s Evolving Attack Techniques

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware remains a threat, and their attack techniques continue to evolve. PWNYOURHOME and FINDMYPWN are the first zero-click exploits we have observed that makes use of two separate remote attack surfaces on the iPhone.

The use of multiple attack surfaces should encourage developers to think holistically about device security, and treat the entire surface reachable through a single identifier as a single surface. For example, an attacker may be able to leak information or set up a framework in one process, and use that information or framework to attack a second process.

Also, it is clear that modern exploit mitigations like pointer authentication codes (PAC) significantly reduce attacker freedom to execute arbitrary code on a device, but as PWNYOURHOME demonstrates, real-world attackers can (and do) find practical ways around these mitigations, such as by repurposing signed pointers located at known offsets in the iOS shared cache. Further work should focus on improvements to legacy code to add meaningful context values to safeguard these pointers.

As we noted in this report, NSO Group’s escalating efforts to block researchers and obscure traces of infection, while still ultimately unsuccessful, underline the complex challenges of these sorts of investigations, including balancing the publication of indicators while maintaining the ability to identify future infections.

Mexico: A Serial Spyware Abuser

The targeting of Mexican civil society with Pegasus spyware is but the latest in a long series of cases dating back to 2016 which we and our partners, and other investigative teams including Amnesty Tech and the Pegasus Project collective, have uncovered in Mexico concerning the abuse of commercial spyware.

A first wave of abuse disclosures (2016-2019) showed widespread targeting of many sectors of Mexican civil society, which all took place during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto. After a change of government, the new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, whose intimate circle was among potential Pegasus targets, claimed that his administration stopped using Pegasus. However, recent reporting, and our collaborative investigations, suggest otherwise.

In March 2023, Mexican civil society groups published documents showing that the Mexican army used Pegasus to hack the device of Raymundo Ramos, a human rights defender investigating yet another massacre involving Mexican army personnel. In October 2022, the Citizen Lab and R3D had reported that Ramos ‘ device was hacked with Pegasus during the same time period in which those documents showed senior Mexican army officials receiving a report summarizing Ramos ‘ private communications with investigative journalists.

It is particularly concerning that human rights defenders representing victims of human rights abuses, including families of the Ayotzinapa students, had their phones hacked with Pegasus spyware. It is widely suspected that individuals connected to the Mexican army were involved in those disappearances, and the subsequent cover-up that followed.

Although we are not conclusively identifying a particular Pegasus operator at this time, the targeting of human rights defenders representing victims of human rights violations in which the Mexican military is involved, in addition to reports and evidence of military involvement in previous recent Pegasus attacks, provides troubling circumstantial evidence suggestive of governmental involvement in these latest cases.

Recommendation: High-Risk Users, Give Lockdown Mode a Try

It is encouraging to see that Apple’s Lockdown Mode notified targets of in-the-wild attacks. While any one security measure is unlikely to blunt all targeted spyware attacks, and security is a multi-faceted problem, we believe this case highlights the value of enabling this feature for high-risk users that may be targeted because of who they are or what they do.

We highly encourage all at-risk users to enable Lockdown Mode on their Apple devices. While the feature comes with some usability cost, we believe that the cost may be outweighed by the increased cost incurred on attackers.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank R3D for their invaluable logistical and investigative assistance with these and other recent cases, especially their director Luis Fernando Garcia.

We also thank Access Now, and especially their Digital Security Helpline for their ongoing collaboration and support in investigating the targeting of high-risk individuals with spyware.

We acknowledge additional collaborators and organizations that refer cases to us, and provide additional investigative assistance.

We thank Siena Anstis, Adam Senft, Paolo Nigro H, and Alberto Fittarelli for review and editing. We thank Mari Zhou for graphical assistance and Snigdha Basu for communications support.