Background and Key Findings

The May 2014 coup d’etat in Thailand was the 19th coup attempt in the country’s history. It stands out from previous coups due to the military junta’s focus on information controls (defined below in more detail). It was also the first time that martial law was imposed before the coup, allowing the military to impose immediate restrictions on freedom of speech, association, and the press. In the 72 hours between the declaration of martial law and start of the coup, the military seized control over the media and restricted speech, both online and offline. By doing so, the military sought not only to silence opposing voices, but also attempt to neutralize a deeply-divided society.

In this report, we document the results of network measurements to determine how the Internet is being filtered and discuss other forms of information control implemented in the coup’s aftermath.

From May 22 to June 26, 2014, we conducted network measurements of website accessibility in Thailand on a number of vantage points to confirm results, identify differences in how ISPs may apply filtering, and to identify centralized filtering infrastructure. We tested a sample of 433 URLs on the following Internet service providers (ISPs): 3BB, INET, and ServeNet (a data centre). We tested a smaller sample of 4 URLs on the ISPs CAT and TOT.

The results identify a total of 56 URLs blocked in the country. The content found blocked includes political content such as domestic independent news media and international media coverage that are critical of the coup, social media accounts sharing anti-coup material, as well as circumvention tools, gambling websites and pornography.

Results of these network tests reveal that blocking in the days following the coup was highly dynamic. The earliest test results did not show any evidence of blocking, but after the first websites were found blocked subsequent test results showed new websites being blocked on a daily basis. The technical methods used to implement blocking were also dynamic, as the blockpages displayed and services used to host them also changed regularly. Tests on 3BB showed three distinct blockpages that appear to be related to the content types being blocked. We also observed different types of content being filtered by the different ISPs tested.Combined, these changes reflect a volatile environment in which the implementation of Internet filtering has shifted rapidly as the coup develops.

The changes in filtering we observed following the coup are happening alongside a series of other measures aimed at monitoring and controlling information in Thailand. For example, the junta created new administrative bodies to monitor and control online content, introduced surveillance of mobile messaging applications, targeted and arrested activists and former government officials based on their social media activities, summoned academics and journalists for questioning, and introduced an application to harvest users’ Facebook credentials. We have seen similar efforts in the past when, following the 2006 military coup, a series of new legislative measures were introduced to control online content. As we will outline below, the events following the 2014 coup indicate that the military junta once again intends to restrict and control the spread of information.

Political Context in Thailand

Thailand has been embroiled in a protracted political conflict since 2005, during the government of the highly popular, but polarizing, former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Thaksin was often criticized by the largely conservative middle class Thais, loosely organized as the “Yellow Shirts,” who saw him as a threat to the monarchy and were critical of what they allege to be cronyism and corruption practiced by Thaksin and his inner circle. After a series of anti-government rallies, Thaksin was removed from power in a military coup in 2006. Despite this, his loyal supporters, mobilized collectively as the “Red Shirts” movement, continued to vote in Thaksin-aligned political parties, including the most recent majority government of the Pheu Thai party, under the leadership of his sister, Yingluck Shinawatra. Thaksin supporters are primarily rural residents who were swayed by policies he introduced that benefited them such as health care and education funding. As a result, color-coded protests and political violence have characterized the Thai political scene for over a decade.

The current political crisis in Thailand has been developing since October 2013, when the Yingluck government sought to pass amnesty bills seen as crucial to the roadmap towards national reconciliation. However these bills were perceived as a ploy to allow Thaksin to return to Thailand while avoiding criminal charges. Widespread opposition rallies ensued led by the Democrat Party, who banded together anti-government groups under the new alliance, the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC). Day after day they occupied major intersections of Bangkok, paralyzing Thailand’s capital city. With no end in sight to the conflict, the government dissolved parliament and called for a snap election to break the stalemate.

The gamble did not pay off as the Democrats boycotted the election and mobilized their PDRC supporters to ban voting, resulting in many electoral irregularities. The Constitutional Court subsequently annulled the election results and, on May 8, 2014, impeached Yingluck on the charge of abuse of power, which set the government into a complete tailspin. On May 20, martial law was declared and the military, citing the need to restore order and stability, formally took over two days later.

Since the coup occurred, the military-run National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has summoned and arrested hundreds of opposition politicians, journalists, activists and academics, imposed a curfew and banned public gatherings of five or more people, and deployed thousands of troops to Bangkok to prevent the spread of protests. In a nationally televised speech, NCPO leader General Prayuth Chan-ocha suggested that it could take more than a year for the junta to implement sufficient reforms to permit an election and a return to civilian rule. The Internet played a key role in the coup and its aftermath. Aside from being broadcast on television, the martial law declaration was also announced through the military’s Twitter account, and Facebook page. Subsequently, measures to restrict the free flow of information on the Internet were implemented, as the military junta has sought to limit the spread of anti-coup messages and increase surveillance of citizens’ anti-coup activities.

Pirongrong Ramasoota, outlines [PDF] in Access Contested: Security, Identity, and Resistance in Asian Cyberspace, that shifts in Thailand’s political landscape have had a history of also impacting the Internet regulatory landscape. For instance, following the September 2006 military coup which overthrew the longest-ruling civilian administration in modern Thai history, the government passed the Computer Crime Act 2007, which has been criticized for its negative impact on freedom of expression on the Internet since it came into force in July 2007.

Information controls in Thailand

Defining information controls

We conceive of information controls as actions conducted in or through information and communications technologies (ICTs), which seek to deny (such as web filtering), disrupt (such as denial-of-service attacks), shape (such as throttling), secure (such as through encryption or circumvention) or monitor (such as passive or targeted surveillance) information for political ends. Information controls can also be non-technical and can be implemented through legal and regulatory frameworks, including informal pressures placed on private companies. Information controls are generic in terms of underlying values, reflecting a range of motivations, and can include efforts undertaken to open up access to information or secure privacy as much as efforts undertaken to do the opposite.

Information controls can be applied in highly dynamic ways that respond to events on the ground. Significant political events such as elections, protests, or conflicts, are important sites of contestation around information controls and include multiple actors, such as states, private companies, criminal or militant organizations, and civil society. It is during these time periods that information has its highest value, and as a result, is the most contested. The 2014 Thailand coup reflects this trend.

Internet Filtering in Thailand

In Thailand, a number of entities are involved in regulating the Internet. The Ministry for Information and Communications Technology (MICT) is responsible for general oversight of ICT policy and development, while the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) regulates, amongst other things, licenses for Internet service and the international Internet gateways.

Although Internet filtering was first introduced in 2002 by a unit of the MICT, information controls were not legislated until the arrival of the Computer Crime Act 2007. Since the Act’s introduction, court orders to block Internet content has increased from 2 URLs in 2007 to over 74,000 in 2012. Examples of content targeted for filtering include pornography, gambling, and terrorism. The government also often invokes lèse-majesté, defined as acts which insult or defame the king or the royal family, as a rationale for the blocking of online content. In 2012, Chiranuch Premchaiporn, the webmaster of popular news portal Prachatai, was given an eight-month suspended sentence for failing to promptly remove user comments deemed insulting to the monarchy.

Our prior research into information controls in Thailand has shown that the implementation of filtering is highly inconsistent among the country’s ISPs.

In 2007 we tested a sample of 1,700 URLs on three ISPs: KSC, LoXinfo, and True. Results found 34 URLs blocked on KSC, 68 URLs on LoXinfo, and 62 URLs on True. Filtering of our test sample on these ISPs primarily focused on content related to pornography, online gambling websites, and circumvention tools. Websites found blocked varied between the three ISPs. LoxInfo and True showed significant overlap in websites filtered. However, only KSC filtered content related to lèse majesté, blocking a number of pages on Amazon.com and other commerce websites featuring censored biographies of the King.

Testing conducted in 2010, following the declaration of a “State of Emergency” after anti-government Red Shirt protesters overran parliament, found that many political opposition sites had been blocked, particularly those related to the Red Shirts. However, like the 2007 results, this filtering was inconsistently applied across ISPs. Out of 36 websites targeted by a post-state of emergency leaked government mandated blocklist, True and TOT blocked 10 and 23 URLs, respectively.

These previous results show that Internet filtering is inconsistently implemented across ISPs and government ordered blocked lists are not uniformly followed.

Information controls and the 2014 coup

On May 20, 2014, the day martial law was declared, the army issued an order suspending normal programming of all television and radio stations and forced them to air military-approved news only. The NCPO also ordered Thai and foreign media not to interview any academics for opinion on the political situation.

On May 21, the NCPO created a working group tasked with coordinating efforts to censor the Internet. This working group consisted of representatives from the MICT, the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) and the army’s “peacekeeping” unit, called the Peace and Order Maintaining Command (POMC). The unit was headed by Pisit Paoin, previously the head of the Thai police’s Technology Crime Suppression (TCSD) division.

On May 22, the day the coup was launched, the junta started exerting pressure on different stakeholder groups and taking further steps to restrict the spread of anti-coup sentiment.

ISPs and telecommunication companies

A military order was released the same day as the coup occurred, which called on ISPs to monitor and deter the publication of information online which may incite unrest in the country. The censorship working group announced that, after meeting with 105 local ISPs, it had blocked six “inappropriate” websites with the cooperation of True Corporation, the country’s largest ISP. Following this meeting, it was also announced that the POMC would summon representatives from major social media services in the country, including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and LINE, to discuss “cooperation” on this issue.

Reports of Internet filtering continued to increase and, on May 24, an MICT representative told the media that the Ministry’s Cyber Security Operation Center (CSOC) had blocked over 100 URLs since the imposition of martial law, although no details were released. On May 27, the MICT announced this number had increased to 219 URLs. Two days later, the NBTC released details on some of the websites targeted for blocking, which included Red Shirt websites and Twitter accounts, an anti-coup Facebook page, and YouTube videos which contravened lèse-majesté regulations.

Social media

Social media is widely used in Thailand. Bangkok has more Facebook users than any other city in the world and Siam Paragon, a shopping mall in Bangkok, is the most Instagrammed location on earth.

The first blocking of a social media platform occurred on the afternoon of May 28, when Facebook was reported to be inaccessible for approximately one hour. The outage was initially blamed on technical issues at the country’s gateway, however, Surachai Srisaracam, permanent secretary of the Information and Communications Technology Ministry, later told media that the action was intended to stop the spread of anti-coup messages. A representative from Norwegian telecom firm Telenor, the majority shareholder of DTAC, the country’s second largest GSM mobile phone provider, later confirmed that the NBTC had ordered access to Facebook restricted. This disclosure led to strong criticism from NTBC, who called the comments “disrespectful” and threatened to stringently investigate DTAC’s shareholding. Telenor would later apologize for publicly disclosing this sensitive information, however they did not suggest it was inaccurate.

Facebook’s shutdown occurred one day before a scheduled meeting between representatives from the military junta and those from social media platforms such as Twitter, Google, and Instagram. That meeting, however, didn’t materialize as the invited companies failed to show up. A scheduled trip to Singapore and Japan to meet with Facebook, Google, and messaging app LINE was also called off after it was deemed unnecessary.

In early June, Thai police warned users that showing support for anti-coup activities by liking a social media post constituted a crime, punishable by up to five years in jail. Soon after, charges were filed against former Education Minister Chaturon Chaisang for his anti-coup statements on Facebook, and in addition, he faces charges of sedition for delivering an anti-coup speech.

Prominent democracy activist Sombat Boonngamanong, also known as Nuling, was arrested by Thai police on June 5 for failing to appear after being summoned by police. Reports emerged that Nuling was located after the IP address of his computer was tracked by Thai intelligence services, who were monitoring his Facebook posts. Nuling had changed his Facebook and Twitter accounts to display the message “Catch Me If You Can”, leading TCSD head Pisit Paoin to respond, “Now we are showing him. We can catch you”.

Thai police have offered rewards of up to 500 baht for pictures of individuals taking part in anti-coup activities, including those from social media, and set up institutions to monitor different types of media for information which shows “hatred towards monarchy”. Broadcast media is monitored by NBTC as the state regulator, print media is monitored by a Special Branch of the Thai Police, online media is monitored by MICT, and foreign media is monitored by the Foreign Ministry.

The junta has also adopted phishing techniques using a Facebook application to collect information on their citizens. After the coup, Thai Netizen Network, a digital rights group, noticed that the TCSD-maintained page that appears when netizens try to access certain blocked websites had a “Login with Facebook” icon. Users were then asked for permission to hand over information stored in their Facebook profile, without any indication, in Thai or English, as to where or for what purpose that data was being sent. EFF reported that the “Login” app was being run by TCSD itself, which used the Facebook app to collect personal details of Facebook users visiting the page.

Chat apps

LINE, a mobile messaging application, developed by Japan-based LINE Corporation, is extremely popular in Thailand. The country has the most LINE users of any market outside of Japan, with 61.1 percent of social media users said to be using the application. Reports indicated that the use of mobile phones spiked soon after the coup, as they provided a way for people to seek and impart information, and therefore, it was unsurprising that the junta thought to use it as a means to surveil their citizens.

The LINE app was singled out by the working group as a tool for surveillance, with working group head Pisit Paoin stating:

“We’ll send you a friend request. If you accept the friend request, we’ll see if anyone disseminates information which violates the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) orders. Be careful, we’ll soon be your friend.”

It is important to note, however, that efforts to monitor mobile messaging applications did not begin with the coup. The TCSD announced plans in August 2013 to monitor conversations on apps such as LINE and WhatsApp to “safeguard the order, security and morality of Thailand”.

Network Measurements of Web Filtering

From May 22 to June 26, 2014, we conducted network tests consisting of HTTP GET requests, traceroutes, and packet captures using client-based measurements, virtual private networks (VPNs), and proxies on the following Internet service providers (ISPs): 3BB (client-based and proxy-based tests) INET (VPN-based tests), ServeNet (VPN-based tests), CAT (Proxy-based tests) and TOT (proxy-based tests).

Our results are grouped below by the specific network vantage point used.

VPN Test Results

Virtual Private Networks (VPN) are a mechanism that allows users to connect to remote networks. We use these services to give us vantage points into Thailand based networks remotely and to observe whether or not filtering is occurring and to which extent. We tested website accessibility via two Thailand based VPNs on the ISPs INET and Servenet.

Data was collected by performing synchronized HTTP requests from the VPN vantage point and from a lab location (at the University of Toronto) using measurement software written in Python. The lab network acts as a control.

During tests the client attempts to access a pre-defined list of URLs simultaneously via the VPN (the “field”) and in a control network (the “lab”). Tests were conducted on URL lists that consisted of locally sensitive URLs that are specific to Thailand’s social, political, and cultural context.

A number of data points are collected for each URL access attempt: HTTP headers and status code, IP address, page body, traceroutes and packet captures. A combined process of automated and manual analysis attempts to identify differences in the results returned between the field and the lab to isolate instances of filtering.

As reports of blocking emerged from the country during the testing period, the list of URLs tested varied slightly over the course of testing to include URLs reported to be blocked. In total, 433 URLs were tested on both VPNs. In a small number of tests, a larger list of internationally relevant content was tested to confirm the breadth and depth of filtering.

INET Results

Tests were conducted on INET between May 22 and June 24, 2014. Test results show that the implementation of blocking has been highly dynamic since the start of the coup. VPN tests run from May 22 until early on May 27, relative to Eastern Standard Time, showed no evidence of blocking.

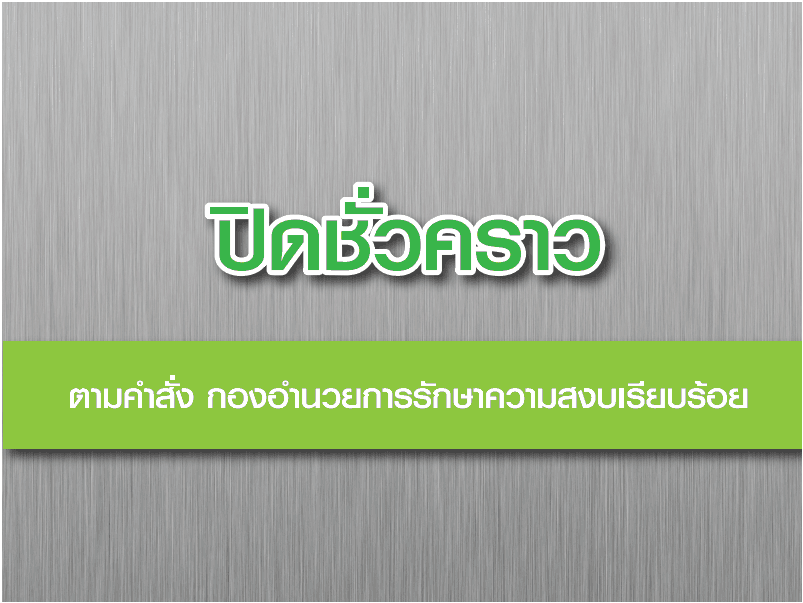

The first evidence of blocked URLs occurred on the afternoon of May 27, when attempts to access blocked content resulted in the following blockpage:

Blocking was implemented by a transparent HTTP proxy which injected a 302 redirection, as seen in the response headers to a request for a blocked URL:

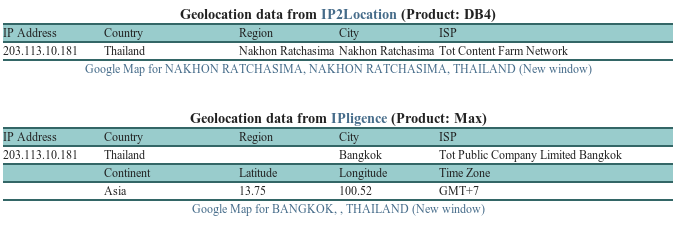

The IP address associated with this domain is 203.113.10.181:

These results show that the blockpage is hosted in Thailand on the ISP TOT, despite the use of dynamic domain provider Dyn for their domain name (kkk.home.dyndns.org).

This is somewhat unusual, as in most cases transparent blockpages are not hosted on such domains. Dynamic domains are most often used by individual users who change IPs frequently and are not often used by large telecommunication companies. Most ISPs have a supply of static IPs as well as the resources and knowledge to register regular domains themselves. One possible explanation is that the ISP wanted to obfuscate who was responsible for blocking the content, although this is not certain.

On June 2nd, a new blockpage was seen when accessing blocked content:

Hosting of this blockpage changed from kkk.home.dyndns.org to block.dyndns-at-home.com, also hosted on TOT and again using a dynamic domain by Dyn:

Autonomous system number (ASN) which denotes which organization is responsible for the IP address is as follows:

| AS | ISP | AS Name |

|---|---|---|

| 9739 | 203.113.26.210 | TOTNET-TH-AS-AP TOT Public Company Limited,TH |

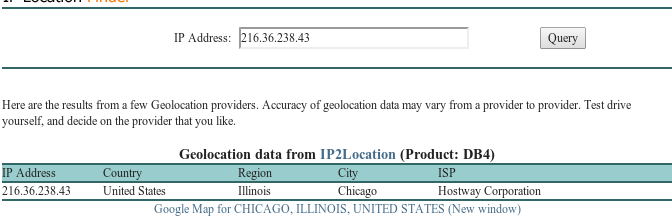

On June 3, the hosting of the blockpage changed to http://blocked.ict-cop.com, which is hosted in Chicago on a U.S.-based hosting provider:

ASN information and geolocation information for this IP address:

| AS | ISP | AS Name |

|---|---|---|

| 20401 | 216.36.238.43 | HOSTWAY-1 – Hostway Corporation,US |

On June 9, 2014, the injected 302 redirection again changed location:

The IP address, 203.113.26.210, is again hosted on the ISP TOT:

| AS | ISP | AS Name |

|---|---|---|

| 9739 | 203.113.26.210 | TOTNET-TH-AS-AP TOT Public Company Limited,TH |

The IP address is the same address as we have seen previously for the domain block.dyndns-at-home.com although the blockpage is no longer using a domain name. The blockpage seen is the same as seen above in Figure 3. These changes in blockpage hosting are summarized below:

| Date | Information | Domain | IP | Hosting Country | Hosting Network |

| May 22nd – May 27th | Blocking Not Observed | ||||

| May 27th | Blocking Observed | http://kkk.home.dyndns.org | 203.113.10.181 | Thailand | TOT Content Farm Network |

| June 2nd | Blocking Observed | http://block.dyndns-at-home.com | 203.113.26.210 | Thailand | TOT Public Company Limited |

| June 3rd | Blocking Observed | http://blocked.ict-cop.com | 216.36.238.43 | USA | Hostway Corporation |

| June 9th | Blocking Observed | 203.113.26.210 | Thailand | TOT Public Company Limited |

Throughout the course of testing, a total of 56 URLs were found to be blocked:

| URL | Content Category |

|---|---|

| http://adultfriendfinder.com | Online Dating |

| http://anonymouse.org | Anonymizers and Censorship Circumvention |

| http://downmerng.blogspot.com | Political Reform |

| http://ibcbet.com | Gambling |

| http://redsiam.wordpress.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://thaienews.blogspot.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://uddtoday.ning.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://weareallhuman.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://weareallhuman2.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.89.com | Pornography |

| http://www.bloggang.com | Groups & social networking |

| http://www.casinotropez.com | Gambling |

| http://www.dangsiam.com | Misc |

| http://www.enlightened-jurists.com | Human Rights |

| http://www.europacasino.com | Gambling |

| http://www.famouspornstars.com | Pornography |

| http://www.fuckingfreemovies.com | Pornography |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/forum/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/home.php | Political Reform |

| http://www.ladbrokes.com | Gambling |

| http://www.midnightuniv.org | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.naughty.com | Pornography |

| http://www.penisbot.com | Pornography |

| http://www.persiankitty.com | Pornography |

| http://www.prachatai.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.redadhoc.org | Political Reform |

| http://www.riverbelle.com | Gambling |

| http://www.spinpalace.com | Gambling |

| http://www.tfn3.info/board/ | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.thaichix.com | Pornography |

| http://www.thaigirls100.net | Pornography |

| http://www.thailandtorrent.com | Peer-to-peer file sharing |

| http://www.thaingo.org | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.wetplace.com | Pornography |

| http://www.worldsex.com | Pornography |

| http://www.youngerbabes.com | Pornography |

| http://www.youtube.com/user/prachatai | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://hidemyass.com | Anonymization and Circumvention |

| http://xvideos.com | Pornography |

| http://beeg.com | Pornography |

| http://ultrasurf.us | Anonymization and Circumvention |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.sportsinteraction.com | Gambling |

| http://www.betfair.com | Gambling |

| http://www.facebook.com/groups/264574313594382/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/index.html | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2638352/how-future-queen-thailand-wearing-tiny-g-string-let-poodle-foo-foo-eat-cake-as-coup-rocks-bangkok-video-reveals-royal-couples-decadent-lifestyle.html | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/pages/no-coup-thailand/234144303452067 | Political Reform |

| http://uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.facebook.com/nuling | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/2yes2no | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net/video/redaksa | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://twitter.com/nuling | Political Reform |

| http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/standing-up-thai-military-coup | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

Blocked URLs fell into a number of content categories, including freedom of expression/media freedom, political reform, pornography, anonymization/circumvention tools and gambling. Some notable websites dealing with critical political content or independent media were blocked, including Prachatai (http://www.prachatai.com), Daily Mail (http://www.dailymail.co.uk), and websites belonging to the United Front for Democracy (UDD) (http://www.uddtoday.net).

A number of Facebook pages were blocked, including that of a group called No Coup Thailand (http://www.facebook.com/pages/no-coup-thailand/234144303452067) and 2 Yes 2 No (http://www.facebook.com/2yes2no).

Websites associated with recently arrested activists and journalists were also found to be blocked. Pro-democracy activist Sombat Boonngamanong (aka Nuling), who was arrested June 5, had his Facebook page (http://www.facebook.com/nuling) blocked, while the website of the legal scholars group Enlightened Jurists (http://www.enlightened-jurists.com), whose members Sawatree Suksri and Worachet Pakeerut were summoned by the junta, was also found to be blocked.

Servenet Results

Tests were conducted on Servenet between June 5 and June 26, 2014. Servenet is a data center and VPS provider and not a traditional ISP, however test results demonstrated that it is also affected by the filtering regime. Tests run on this ISP via VPN similarly showed variability in the implementation of filtering.

The first test was run on June 5, 2014, and showed evidence of blocking by redirection to blocked.ict-cop.com, as seen on INET. However by June 7, blocking was implemented in a similar manner to that seen on INET. Attempts to access blocked content were redirected to the IP 203.113.26.210, as seen in the following server response headers when accessing a blocked URL:

This IP address, 203.113.26.210, is hosted on the ISP TOT:

| AS | ISP | AS Name |

|---|---|---|

| 9739 | 203.113.26.210 | TOTNET-TH-AS-AP TOT Public Company Limited,TH |

This redirection leads to the same blockpage seen on INET, as shown in Figure 3 above. These changes in blockpage hosting are summarized below:

| Date | Information | Domain | IP | Hosting Country | Hosting Network |

| June 5-6 | Blocking observed | http://blocked.ict-cop.com | 216.36.238.43 | USA | Hostway Corporation |

| June 7-26 | Blocking observed | 203.113.26.210 | Thailand | TOT Public Company Limited |

The following URLs were found blocked on this ISP:

| URL | Content Category |

|---|---|

| http://downmerng.blogspot.com | Political Reform |

| http://ibcbet.com | Gambling |

| http://redsiam.wordpress.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://thaienews.blogspot.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://uddtoday.ning.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://weareallhuman.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://weareallhuman2.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.bloggang.com | Groups and Social Networking |

| http://www.dangsiam.com | Misc |

| http://www.enlightened-jurists.com | Human Rights |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/forum/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/home.php | Political Reform |

| http://www.ladbrokes.com | Gambling |

| http://www.midnightuniv.org | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.redadhoc.org | Political Reform |

| http://www.tfn3.info/board/ | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.thaichix.com | Pornography |

| http://www.thaigirls100.net | Pornography |

| http://www.thailandtorrent.com | Peer-to-peer file sharing |

| http://www.thaingo.org | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.youtube.com/user/prachatai | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://politicalprisonersofthailand.wordpress.com | Human Rights |

| http://www.facebook.com/groups/264574313594382/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/index.html | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2638352/how-future-queen-thailand-wearing-tiny-g-string-let-poodle-foo-foo-eat-cake-as-coup-rocks-bangkok-video-reveals-royal-couples-decadent-lifestyle.html | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/pages/no-coup-thailand/234144303452067 | Political Reform |

| http://uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net/video/redaksa | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://twitter.com/nuling | Political Reform |

| http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/standing-up-thai-military-coup | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.hrw.org/asia/thailand | Human Rights |

| http://www.pinnaclesports.com | Gambling |

Client-based test results

We conducted client-based tests from within Thailand. This data was collected using the same method as described in the VPN test results section. Tests were conducted on the ISP 3BB on June 25, 2014. A total of 433 URLs were tested during this period. 33 of these URLs were found to be blocked through three different methods: The first blocking method on this ISP is through the use of a transparent proxy which injected a 302 redirection to 203.113.26.210, as seen here in this HTTP request/response pair:

This IP address is hosted on the ISP TOT:

| AS | ISP | AS Name |

|---|---|---|

| 9739 | 203.113.26.210 | TOTNET-TH-AS-AP TOT Public Company Limited,TH |

The redirection leads to the same blockpage seen on INET, shown above in Figure 3. This blockpage has the following HTML source:

The following 20 URLs were found blocked through this method:

| URL | Content Category |

|---|---|

| http://redsiam.wordpress.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://thaienews.blogspot.com | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.dangsiam.com | Misc |

| http://www.enlightened-jurists.com | Human Rights |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/forum/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.konthaiuk.com/home.php | Political Reform |

| http://www.midnightuniv.org | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/groups/264574313594382/ | Political Reform |

| http://www.facebook.com/reddemocracy?ref=profile | Political Reform |

| http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/index.html | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/pages/no-coup-thailand/234144303452067 | Political Reform |

| http://uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net | Political Reform |

| http://www.facebook.com/nuling | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.facebook.com/2yes2no | Political Reform |

| http://www.uddtoday.net/video/redaksa | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://twitter.com/nuling | Political Reform |

| http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/09/standing-up-thai-military-coup | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.hrw.org/asia/thailand | Human Rights |

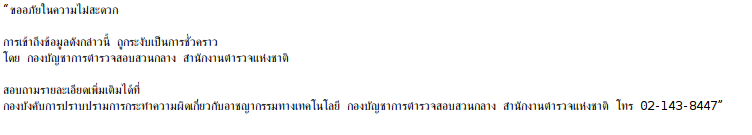

The second method was also through a transparent proxy which returns the following blockpage text:

Which translates to:

The following seven URLs were found blocked through this method:

| URL | Content Category |

|---|---|

| http://weareallhuman.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://weareallhuman2.info | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.internetfreedom.us | Political Reform |

| http://www.ladbrokes.com | Gambling |

| http://www.tfn3.info/board/ | Freedom of Expression and Media Freedom |

| http://www.thaigirls100.net | Pornography |

| http://thaipoliticalprisoners.wordpress.com | Human Rights |

| http://www.pinnaclesports.com | Gambling |

Finally, the third blocking method, like the first, was also implemented through a transparent proxy which injects a 302 redirection, as seen in this set of server response headers for a blocked URL:

This site, tcsd.info, is hosted in Thailand and displays the following blockpage:

The blockpage seen in Figure 4 is the same page which contained a link to a Facebook application which was found to be improperly harvesting user’s credentials, as described above. The following five URLs were found blocked through this method:

| URL | Content Category |

|---|---|

| http://ibcbet.com | Gambling |

| http://www.gboysiam.com | Gay and Lesbian – no pornography |

| http://www.thailandtorrent.com | Peer-to-peer file sharing |

| http://sportsbook.sportdafa.com/th | Gambling |

| http://www.188bet.com | Gambling |

It is unclear why we see three separate implementations of blocking on this ISP. The first blockpage, shown in Figure 3, appears to have been introduced after the coup, and the content found blocked through this method is generally critical of the coup. The second and third methods showed a broader variety of content blocked and are likely methods of blocking introduced before the coup.

Proxy Test Results

Tests were conducted via a number of publicly accessible web proxies located in Thailand. The primary purpose of this testing was to determine how the implementation of filtering varied between ISPs, and to permit testing on ISPs for which we did not otherwise have visibility into. We used proxy vantage points to test access to a sample of four URLs from May 29th to June 4, 2014. These four URLS were all found blocked through VPN and client-based testing on other ISPs:

- http://www.tfn3.info/board/

- http://www.enlightened-jurists.com

- http://www.ibcbet.com

- http://www.youtube.com/user/prachatai

These tests of this small sample of URLS showed that these URLs were blocked consistently across ISPs, with only two instances of one of the above URLs found to be accessible. More comprehensive testing on these ISPs would be required to determine how consistent filtering was across a larger testing list.

CAT Telecom

Attempts to access URLs #1, 3, and 4 on May 29, 2014, on a proxy based on the ISP CAT Telecom redirected to a blockpage hosted at http://w3.mict.go.th/blocked.html, although the blockpage did not load successfully. By June 3rd, tests of URL #1 on this same proxy displayed the blockpage seen above in Figure 3.

3BB

Attempts to access URL #3 on May 29, 2014 on a proxy on the ISP 3BB displayed the following blockpage:

This blockpage text translates to:

On May 30th, tests of URL #2 on a proxy on the ISP 3BB displayed the following blockpage:

This blockpage text translates to:

TOT

Attempts to access URLs #3 and 4 on May 29th on a proxy on the ISP TOT displayed the same blockpage seen on INET in Figure 1. Attempts to access URL #1 on May 30, 2014, on a proxy hosted on the ISP TOT displayed the same blockpage seen on INET in Figure 3. These results demonstrate that while most content from this small sample was blocked on the ISPs tested, blocking was both implemented differently and was highly dynamic during the early days of the coup.

Conclusion

After the 2006 Thai coup, the government engaged in a crackdown on activists, increased filtering of websites, and implemented new laws governing online content, thus altering the landscape of information controls. The weeks following the 2014 coup have shown a similar dynamic, as the government seeks to erect new forms of information control in response to the crisis. Whether and to what extent these information controls affect the ICT landscape in Thailand in years to come remains to be seen. In this report, we have focused our attention primarily on information controls exercised by the state. However, events, such as coups, are multi-faceted and dynamic, and the contests over the information and communications environment will include citizens and private companies who will play a role in shaping the ICT environment in Thailand in the weeks and months ahead. The Citizen Lab will continue to monitor developments in Thailand and report new findings as they become available.

Data

A complete list of URLs tested and URLs found blocked, for each ISP test, can be found here.

A collection of blockpages identified during this testing can be found here.

Acknowledgements

Adam Senft, Jakub Dalek, Irene Poetranto, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, and Aim Sinpeng undertook research and writing of this report, supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canada) Grant 430-2014-00183, Prof. Ronald J. Deibert, Principal Investigator.