Key findings

- We analyzed Apple’s filtering of product engravings in six regions, discovering 1,105 keyword filtering rules used to moderate their content.

- Across all six regions we analyzed, we found that Apple’s content moderation practices pertaining to derogatory, racist, or sexual content are inconsistently applied and that Apple’s public-facing documents failed to explain how it derives their keyword lists.

- Within mainland China, we found that Apple censors political content including broad references to Chinese leadership and China’s political system, names of dissidents and independent news organizations, and general terms relating to religions, democracy, and human rights.

- We found that part of Apple’s mainland China political censorship bleeds into both Hong Kong and Taiwan. Much of this censorship exceeds Apple’s legal obligations in Hong Kong, and we are aware of no legal justification for the political censorship of content in Taiwan.

- We present evidence that Apple does not fully understand what content they censor and that, rather than each censored keyword being born of careful consideration, many seem to have been thoughtlessly reappropriated from other sources. In one case, Apple censored ten Chinese names surnamed Zhang with generally unclear significance. The names appear to have been copied from a list we found also used to censor products from a Chinese company.

Introduction

China is a highly profitable market for tech companies. However, the Chinese tech sector is one of the most heavily controlled industries. Internet companies operating in China are held responsible for content that appears on their products and are expected to dedicate human and technological resources to ensure compliance with local content laws and regulations. These laws and regulations are often vaguely defined and largely motivated by protecting the political interests of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In addition to content regulations, China introduced its first Cybersecurity Law in 2017 that requires foreign companies to store user data in mainland China, which has led to speculation as to whether Internet companies would turn over user data to the Chinese government without due process. Failure to comply with government regulations in China can lead to heavy fines and revocation of business licences, and, for foreign companies, it might mean losing access to the Chinese market entirely.

Apple’s China Entanglement

Apple has enjoyed much success in China in recent years. Sales in the Greater China region hit a record high in its December quarter in 2020. The mainland Chinese market makes up nearly a fifth of Apple’s total revenue. Additionally, Apple assembles almost all of its products in China. Apple’s heavy dependence on the mainland Chinese market and manufacturing, however, has given rise to growing concerns over the leverage that China holds over Apple and criticism of how Apple proactively implements censorship to please the Chinese government in order for Apple to advance its commercial interests in the region. Moreover, Apple’s proactive measures are often found implemented beyond mainland China.

Political Censorship in the Apple Ecosystem

Most work analyzing how Apple politically restricts its users has looked at Apple’s censorship of its own App Store. Unlike other phone platforms, such as Google’s Android platform, that allow the installation of apps from sources outside of Google’s Play Store, Apple’s platform follows a “walled garden” model, meaning that Apple’s users can only run apps that Apple approves of in its App Store. While this monopolistic control of the app market on its devices financially profits Apple by enabling them to tax transactions made using their devices, this single point of control also allows censorship by different governments, censorship which Apple has often been willing to facilitate.

Much work has looked at Apple’s political censorship of its App Store in China. In July 2017, Apple purged its Chinese App Store of major VPN apps, tools that might be used to circumvent China’s national censorship firewall. By May 2021, Apple had reportedly taken down tens of thousands of apps from its Chinese App Store, including foreign news outlets, gay dating services, and encrypted messaging apps, as well as an app that allows protesters to track the police from its Hong Kong App Store. According to Apple’s own transparency reports, the company has removed nearly 1,000 apps in mainland China over the past few years as per government requests. However, observers note that Apple is often doing more than just the bare minimum to comply with China’s laws and regulations, as it has “built a system that is designed to proactively take down apps — without direct orders from the Chinese government — that Apple has deemed off limits in China, or that Apple believes will upset Chinese officials.” Advocacy groups argue that Apple’s app censorship exceeds that required by Chinese law and that Apple’s real concern is to not “offend the Chinese government.”

Outside of China, Apple also faced criticism from other civil society groups for censoring LGBTQ+ content in its App Store in over 150 countries, which is in sharp contrast to the company’s pro-LGBTQ+ stance in the United States. Popular LGBTQ+ and dating apps such as Grindr, Taimi, and OkCupid are unavailable in more than 20 countries.

In addition to its App Store, Apple politically censors other aspects of its platform as well. For instance, in 2019, Apple Music removed a number of Hong Kong originating songs and artists from its mainland Chinese streaming service allegedly for political reasons. Later the same year, Apple was found to have censored the Taiwan flag emoji for users that have their iOS region set to Hong Kong or Macau. Apple had only previously applied such censorship to users who had set their iOS region to mainland China.

Censoring Apple Product Engravings

This report investigates Apple’s content control of its product engravings, a feature Apple provides when ordering some of its products to print messages on their exteriors. While we found that there exists no publicly accessible document or guideline outlining what rules and limitations applied to consumers’ personalized engravings on Apple products, there has been some previous reporting on Apple’s content control of product engravings. Journalists recently reported that certain words are prohibited from being engraved on Apple’s AirTags. According to the article, while offensive language such as “SLUT” or “FUCK” are filtered, “NAZI” is allowed to be engraved on Apple products. Previous news coverage looking at iPad engravings suggested that Apple restricted certain mainland Chinese political words from appearing on its products in Hong Kong or mainland China, but it was unclear what or how many keywords were censored in the Chinese market. A recent report by China Digital Times has documented several blocked keywords on Apple’s new AirTag products.

Such product customizations have a history of being used for political expression, as well as being subject to political censorship exceeding that required by companies’ public policies. In 2001, as part of a Nike service in which customers could embroider custom messages on their shoes, future Buzzfeed founder Jonah Peretti, in protest of Nike’s labor practices, chose the word “sweatshop” to be embroidered. However, Nike responded by cancelling his order, despite it not violating any of Nike’s published rules. In 2020, a Hong Kong resident going by the alias “Mr. Chen” reported that he requested to have the phrase “liberate HKERS” engraved on an Apple product. Even though Apple’s automatic keyword filtering did not censor the phrase, an Apple employee later contacted Mr. Chen, saying that the “higher-ups did not approve” of the message. In response to the employee’s insistence that communication occur over the phone, frustrated by Apple’s lack of public policy on this matter, Mr. Chen stated that Apple would not correspond over email because “they did not want it written down in black and white.”

In this report, we analyze Apple’s censorship practices in six regions―mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Canada, and the United States―for a comparative look into whether and how the global company moderates content on its products, including the extent to which the company politically censors product engravings. Across all six regions, we found that Apple’s content moderation practices pertaining to derogatory, racist, or sexual content are inconsistently applied and that Apple’s public-facing documents failed to explain how it determines the keyword lists. Within mainland China, we found that Apple censors political content including broad references to Chinese leadership, China’s political system, names of dissidents, independent news organizations, and general terms relating to democracy and human rights. Moreover, we found that much of this political censorship bleeds into both Hong Kong and Taiwan. Some of the censorship exceeds Apple’s legal obligations in Hong Kong, and we are aware of no legal justification for the political censorship of content in Taiwan.

Legal Environment

The jurisdictions we included in this analysis have different regulatory and political environments that may affect a company’s filtering decisions and content moderation policies writ large. To contextualize our research, we provide a brief background on the legal and political factors in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Canada, and the United States which could potentially apply to Apple’s product engraving services in those regions. However, we reviewed legal documents on Apple’s websites in each of the six jurisdictions and have not found any public-facing policy documents that explain or regulate what users can or cannot engrave on Apple products.

China

China accounts for nearly one fifth of Apple’s revenues, but the Chinese market carries unique challenges. First, the publication and circulation of information in China is strictly regulated both online and offline. Any publications, decorations, and other printed materials that contain “reactionary, pornographic, or superstitious contents and other contents publicly prohibited by state orders” are forbidden from printing. However, there are no publicly accessible government directives that give specific instructions on what content is considered “reactionary, pornographic, or superstitious.” In many cases, publishers and private companies in general bear the responsibility to ensure printed materials stay within government regulations.

Moreover, China’s information and communications technology (ICT) sector is one of the most highly regulated and restricted industries in the country. Foreign and foreign-invested companies are barred from directly participating in certain ICT sectors such as online publishing, Internet streaming, video games, and Internet cultural activities in general. Depending on the product, foreign companies may either set up a Chinese subsidiary or partner with a local Chinese company to legally enter the Chinese market. ICT companies operating in China are subject to laws and regulations that hold companies responsible for content on their products and platforms. Additionally, companies are expected to share with the state personal information of users who are suspected of violating content laws and regulations. On several occasions, such sharing has resulted in suspensions of user accounts and at times the arrest and prosecutions of journalists, activists, and dissidents. For companies, failure to comply with content regulations may lead to official reprimands, fines, or even revocation of business licences, which has encouraged companies to self-censor to avoid troubles from the government.

Previous research has uncovered that foreign ICT products, including mobile games and social media platforms, often end up implementing automated keyword-based censorship that caters to mainland Chinese political sensitivity when operating in mainland China. Moreover, as China is able to increase its economic leverage over companies, there is growing concern over whether Chinese-owned companies or companies that rely significantly on the Chinese market would export politically-motivated censorship beyond mainland China and allow only narratives that align with the Chinese government’s stances. WeChat, the world’s fourth largest social media application owned and operated by Chinese Internet giant Tencent, for instance, has been found to surveil communications between international users to train its censorship apparatus targeting mainland Chinese users. Chinese-owned social media platform TikTok, which consistently surpassed the popularity of all U.S.-owned platforms worldwide over the past few years, was found to accidently censor content deemed critical of the Chinese government for international users. In addition to playing by local content regulations in the China region to help its products break into the Chinese market, Microsoft’s China-intended censorship rules were occasionally enabled globally, further worrying critics of information control.

Apple has repeatedly cited compliance with Chinese regulations as part of doing business in mainland China. In 2016, Apple set up its first data center in China in response to the country’s data localization regulations. It also partners with government-owned Guizhou-Cloud Big Data Industry which handles all iCloud data belonging to Chinese citizens residing in mainland China. While data localization is increasingly common in different jurisdictions, legal and security experts worry that Apple would not be able to prevent the Chinese government from accessing users’ sensitive and private information. Most recently, in June 2021, Apple released a new “private relay” feature designed to obscure a user’s web browsing behaviour from Internet service providers (ISPs) and advertisers. However, Apple will not make this feature available in mainland China, citing “regulatory reasons.”1

Hong Kong

Hong Kong, a Special Administrative Region of China, has a regulatory system pertaining to its ICT sector that is independent from mainland China. As one of the most liberalized markets in Asia, there are currently no foreign ownership restrictions in Hong Kong. Freedom of expression is also protected by Article 27 of the Basic Law and Article 16 of the Bill of Rights Ordinance in Hong Kong. However, there are rising concerns that such protection is deteriorating. In late 2015, five staff members of Causeway Bay Books, a former Hong Kong-based bookstore known for publishing political tabloids and books critical of the Chinese leadership, were detained and interrogated in mainland China.

The promulgation of Hong Kong’s National Security Law (NSL) in June 2020 has further added to the uncertainty as to whether the central government and local authorities would begin regulating content and policing speech broadly and arbitrarily citing national security concerns. Article 43 of the NSL gives law enforcement authorities in Hong Kong the power to “requir[e] a person who published information or the relevant service provider to delete the information or provide assistance” when handling cases concerning offence endangering national security. A recent report showed that the newly enacted NSL has been actively invoked to arrest and charge opposition politicians and activists or individuals who expressed certain forms of political speech. Earlier this year, Hong Kong’s mobile telecom companies were found to have blocked access to a website that provides information about anti-government protests in compliance with the NSL. Hong Kong Internet Registration Corporation Limited, the company that approves Internet domains in Hong Kong, also updated its domain registration policies in January 2021, stating that it may cancel a domain registration if it believes that the registrant has used or is using the domain for “illegal activities.” In August 2020, Apple managers in Hong Kong reportedly banned employees from expressing support for the city’s pro-democracy movement.

Taiwan

Taiwan, on the other hand, faces a different challenge of balancing freedom of speech and regulations on misinformation, disinformation, and politically-motivated narrative manipulation. In December 2020, Taiwan faced controversies when it refused to renew the license of a news channel widely considered pro-China, citing evidence of interference from a Beijing-friendly tycoon. At the same time, research suggests that the island was targeted by both politically- and commercially-driven disinformation campaigns during the pandemic and its 2020 elections.

In general, Article 34 of the Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area restricts items imported from mainland China from containing mainland Chinese propaganda. Moreover, Article 20 of Compliance Approval Regulations of Telecommunications Terminal Equipment authorizes revocation of telecommunication equipment certificates when any such equipment’s firmware harms “national dignity”, a law primarily used to address cases where imported Huawei, Xiaomi, and Vivo phones list Taiwan as “Taiwan, Province of China” in their operating system. However, while these laws concern themselves with restricting Chinese propaganda and protecting Taiwanese national dignity, the political censorship pertaining to Apple’s Taiwan region which we discovered in this report appears to align with mainland Chinese propaganda and content restrictions. Overall, there is no law or regulation that prohibits companies or users in Taiwan from publishing or circulating content due to it being politically sensitive in mainland China.

Japan, Canada, and the United States

In Japan, Canada, and the United States, government-mandated political censorship is rare. Apple’s decisions to filter keywords on product engraving in these regions may be motivated by reputation management and guided by social norms regarding what is offensive speech in a given society. For example, content moderation of Apple product engravings in Canada may reflect the ongoing societal debate over what content is allowed on vanity license plates. For instance, the government of Ontario in Canada allows personalized licence plates as long as the personalized message is considered “appropriate” and does not contain sexual messaging, vulgar and derogatory slang, religious language, references to the use or sale of drugs, violence-linked messaging, or other discriminatory terms. In the United States, local motor vehicle commissions sometimes apply Title 39 of the United States Code to the regulations of vanity plates, ensuring that “offensive to good taste or decency in any languages” is prohibited from personalized plates. Phrases such as “JAP”, “BIOCH” and “GAY” were reportedly rejected in different states.

Past reports suggest that Apple’s engraving policies in these regions are often inconsistent, non-transparent, and at times sexist. A 2014 article found that Apple allowed the word “penis” to be engraved on its products but not the word “vagina.”

Technical Analysis of Apple Engraving Filtering

We analyzed how Apple engravings were filtered in six different regions recognized by Apple: United States, Canada2, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong3, and mainland China. In this section, we explain the technical implementation of Apple’s filtering of engravings across these regions.

When inputting an engraving, we found that the Web UI validated the engraving as a user enters the engraving character-by-character (see Figures 1 and 2).

Although engravings for AirTags are limited to only four characters, iPad engravings can be much longer, and on iPads the number of characters allowed is dependent on the width of the entered characters.

| Region | Product | API endpoint |

|---|---|---|

| United States | AirTag | https://www.apple.com/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532AM%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3LL%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed | |

| Canada | AirTag | https://www.apple.com/ca/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532AM%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com/ca/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3VC%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed | |

| Japan | AirTag | https://www.apple.com/jp/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532ZP%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com/jp/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3J%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed | |

| Taiwan | AirTag | https://www.apple.com/tw/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532FE%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com/tw/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3TA%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed | |

| Hong Kong | AirTag | https://www.apple.com/hk-zh/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532ZP%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com/hk-zh/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3ZP%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed | |

| Mainland China | AirTag | https://www.apple.com.cn/shop/validate-engraving?product=MX532CH%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&f=mixed |

| iPad | https://www.apple.com.cn/shop/validate-engraving?product=MHQR3CH%2FA&msg.0=[ENGRAVING]&msg.1=&f=mixed |

Table 1: Each region’s API endpoints for filtering engravings on AirTags and iPads. Note that iPads can engrave a second line, which is stored in the “msg.1” parameter.

We found that each region verifies engravings using a different API endpoint (see Table 1), facilitating different filtering rules for each region. Each endpoint returns a JSON response indicating whether there are any errors with the inputted engraving (see Figure 4).

{

"body" : {

"content" : {

"errors" : {

"0" : "请重新提交你的镌刻信息。镌刻字母缩写、幸运数字和喜爱的表情符号,刻出你的十足个性。"

},

"hasErrors" : true,

"partNumber" : "MX532CH/A"

}

},

"head" : {

"data" : {},

"status" : "200"

}

}

We found that different regions allow different character scripts, typically consistent with the language or languages spoken in that region. For instance, for users in the Taiwan region, certain simplified Chinese characters are unsupported, as such characters, while common in mainland China, are not typically used in Taiwan, and users in the United States and Canada may not use Chinese characters at all.

By testing different engravings, we found that the following steps are used to filter Apple AirTag engravings across all regions in the following order. We measure the order of the filters by attempting engravings that trigger multiple filters and then measuring which error message is returned. For instance, in an engraving that includes illegal keyword content but also characters of a script unsupported in that region, we found that the error message for illegal keyword content is returned. Thus we say that the illegal keyword filtering is effectively performed before filtering for unsupported characters. Note that we provide the error messages returned below for AirTag engravings in the US region, but we found that the error messages were localized for each region, appearing in each region’s language.

- Security filtering: If the engraving contains one of many common HTML tags (e.g., “<b>”), if the engraving resembles SQL content (e.g., “; DELETE FROM”), or if the engraving is an HTTP URL containing an IP address (e.g., “http://127.0.0.1”) then the API crashes and returns an HTTP 403 code and an HTML error page as opposed to the expected JSON response. This response is reported in the Web UI as “Something went wrong. Please try again or check back later.” This filtering may be a naive method of protecting against attacks such as XSS (cross-site scripting) or SQL injection attacks. Using blacklisting to prevent such attacks is neither necessary nor sufficient and, when solely relied upon, may lend itself to a false sense of security.

- (AirTag only) Lowercase filtering: If the engraving contains any lowercase letters, English or otherwise, then the API returns the following error: “Lower-case characters are not supported.” For AirTag engravings, Apple’s Web UI automatically capitalizes letters, so this error is typically only observed when querying the API directly. This filtering is applied to only AirTag engravings, as iPad engravings allow lowercase letters.

- (AirTag only) Character count filtering: If an AirTag engraving contains more than four characters, then the API returns the following error: “Your message does not fit in the available space.” This filtering does not apply to iPad engravings.

- Keyword filtering: If the engraving is filtered according to one of the user’s region’s keyword filtering rules, then the API returns the following error: “Please resubmit your engraving message. Personalize with your initials, lucky numbers, and favorite emoji.”

- Character filtering: If the engraving contains characters that are of a script unsupported in the user’s region, then the API returns the following error: “These characters cannot be engraved: [CHARACTERS].” “[CHARACTERS]” is a list of characters that appeared in the engraving that are unsupported in the user’s region. As examples, Chinese characters are not allowed in the United States region, Korean characters are not allowed in the mainland China region, and so on.

- Width filtering: If the engraving does not fit in the physical width provided by the product, then the API returns the following error: “Your message does not fit in the available space.” Whereas AirTags are small and can only fit shorter engravings, iPad engravings can be much longer. The width filtering rarely triggers on AirTag engravings since AirTag engravings are already limited to four characters, but the filtering can still apply to AirTag engravings if very wide characters are chosen, such as four W letters (WWWW).

As a consequence of keyword filtering being performed before character filtering, we discovered that we can measure when a region filters keywords that contain characters unsupported in that region. For instance, in the mainland China region, “포르노”, a Korean word for pornography, is filtered, and entering it would yield a keyword filtering error, but Korean characters are generally unsupported in the mainland China region, and entering any of the Korean characters in “포르노” on its own would result in a character filtering error. Thus, we can measure the existence of keywords filtered in a region even if those keywords contain characters that are unsupported in engravings for that region.

Among these six filters, the remainder of our work in this report focuses on characterizing and measuring Apple’s implementation of keyword filtering, their system used to reject engravings depending on whether they contain filtered keyword content. We study how this system filters keywords, identify which keywords Apple filters in which regions, and characterize the filtered content and the motivations for its filtering across different regions.

Technical analysis of keyword filtering

In this section we describe certain technical details concerning how Apple implements keyword filtering of users’ product engravings. Consider the keyword “POO”, a keyword filtered that we found filtered in all six regions that we analyzed. In a region where “POO” is a filtered keyword, then certainly the engraving “POO” is filtered, but what about variations of it, such as “PXOO” (adding something inside the keyword) or “XPOOX” (adding something outside the keyword)? What about when the additional characters are punctuation, such as “P-OO” or “-POO-”? We describe how the system matches keywords to engravings in the following two sections.

Keyword infusion rules

In this section, we explain how certain characters may be infused inside a keyword without preventing it from triggering filtering. While we found that inserting most characters in between a keyword’s characters generally evaded filtering, we found that by inserting certain punctuation or spacing in between a keyword’s characters, the keyword would still be filtered. For instance, in regions where “POO” is filtered, then so is “P.O O” (POO with a full stop before the first O and a space before the second O) as well as “P-O_O” (POO with a hyphen before the first O and an underscore before the second O), but “PXOO” is not filtered, as “X” is not one of these specific punctuation or space characters. Not all punctuation behaves this way, as infusing some other punctuation such as commas or semicolons in between characters of the keyword causes the word to no longer be filtered. We were able to identify the following six characters that could be infused in between a keyword’s characters without preventing it from being filtered: “ ” (space), “.” (full stop), “-” (hyphen), “_” (underscore), “*” (asterisk), and “★” (star).

Keyword wildcard rules

In the previous section, we describe rules that govern which characters may occur in between a keyword’s characters. This section is concerned with which characters can occur adjacent to a keyword, i.e., immediately to its left or to its right, according to its wildcard rules.

We found that a keyword can always occur as part of a larger engraving if surrounded by certain punctuation or spacing characters. For instance, for any filtered keyword ABC, a sentence like “I LOVE ABC A LOT” or string like “XXX.ABC_YYY” will still be filtered, as spaces, full stops, and underscores are among the punctuation and space characters that can always immediately surround a filtered keyword without preventing it from being filtered.

We found that some keywords can trigger filtering regardless of which characters immediately surround them. However, possibly motivated by the Scunthorpe problem, a recurring issue in which the town of Scunthorpe, U.K., found its name censored by automatic keyword filtering systems due to the name containing a common English profanity as a substring (the second through fifth letters), Apple does not allow all filtered keywords to trigger in any context. Thus, for a filtered keyword ABC, whether “XXXABC”, “ABCYYY”, or “XXXABCYYY” are filtered depend on the filtered keyword’s wildcard rules, which determine whether any character can occur immediately to the left, immediately to the right, or immediately on both sides of the keyword.

| Filtering Rule | Engraving | Filtered? | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| POO | POO | Yes | Because POO is a filtered keyword |

| POO | SPOON | No | Because POO has no wildcard matching on its left or right |

| POO | S.POO N | Yes | Because certain punctuation or spacing immediately separates POO from adjacent letters |

| *POO* | SPOON | Yes | Because *POO* has wildcard matching on both the left and the right |

| *POO* | PEEKABOO | No | Because “EEKAB” are not among the special punctuation and space characters that can be infused in a keyword |

Table 2: Example keyword filtering rules.

We discovered four different possible rules, which we will annotate by positioning asterisk (*) characters on either the left, right, both, or neither sides of a keyword. A bare keyword filtering rule POO will not trigger filtering except on input that is identical to itself or on input where it is immediately surrounded by special punctuation or space characters. Thus, POO would filter “POO” and “S.POO N” but not filter “SHAMPOO”, “POOL”, or “SPOON”. Conversely, the rule *POO* would filter “SHAMPOO”, “POOL”, “SPOON”, as the asterisks on both sides indicate that POO can be surrounded by any character on the left or right. Similarly, *POO would filter SHAMPOO but not POOL or SPOON, while POO* would filter POOL but not SHAMPOO or SPOON.

In our results, we discovered that a keyword filtered in two different regions can have different wildcard matching rules in each region. For instance, we found that BUNGHOLE (with no wildcard matching) filters engravings in some regions, whereas BUNGHOLE* (with wildcard matching on the right but not the left) filters engravings in other regions. As such, as a matter of terminology, in this report we call BUNGHOLE, the word itself, a keyword which we have observed to have two different keyword filtering rules, BUNGHOLE and BUNGHOLE*.

Methods

To understand which content is filtered in each of the regions we investigated, we performed the following experiment. In our experiment, we utilize sample testing to test whether engravings are filtered in different regions. To serve as test samples, we aggregated 505,902 previously discovered keywords censored across a variety of Chinese applications including WeChat and other chat apps, live streaming apps, and mobile games and in a variety of open source GitHub projects. For each region, we then used that region’s API endpoint to validate each keyword test sample and recorded the result. As it became evident early in our investigation that AirTag engravings and iPad engravings used the same keyword filtering rules, we performed our testing on only iPad engravings, as these engravings were allowed to be much longer than the four characters allowed by AirTag engravings and thus were capable of revealing filtered keywords longer than four characters. If the API returned a response indicating that the engraving failed the keyword check (see the previous section for details), then we consider that engraving filtered in the region tested.

Once we have discovered an engraving that is filtered, we still need to determine the keyword rule triggering that engraving’s filtering. To determine the keyword filtering rule, we first isolate the exact keyword triggering the filtering. We do this by performing an automated series of mutations to the engraving, observing which mutations cause the engraving to no longer be filtered.

First we attempt to iteratively trim unnecessary characters from the end of the engraving. To do this, for an engraving “ABCDE”, we test the following two engravings:

- ABCD"E

- ABCD

If both of those two engravings are still filtered, then we have eliminated “E”. We reduce our engraving to “ABCD” and iteratively perform the test again, attempting to eliminate the new last character “D”. The first test separating the engraving’s last character with a double quote is necessary to distinguish rules which are the same except that one has an additional character at the end. For example, consider the keyword filtering rules CONDOM and CONDOMS. If we only tested whether we could delete characters from the end of the engraving, then if our initial engraving was “CONDOMS.”, then we would correctly eliminate the full stop (.) yielding “CONDOMS”, but if we subsequently tried deleting the S, then we would find that the subsequent engraving “CONDOM” is still filtered. However, this isolation would be spurious, as only CONDOMS, not CONDOM, is responsible for filtering the engraving “CONDOMS.”. By testing “CONDOM"S” in addition to “CONDOMS”, we can distinguish between these two rules, as even though “CONDOMS” is filtered, “CONDOM"S” is not.4 On any iteration, if either of these two test engravings are not filtered, then we are done iteratively trimming characters from the end of the engraving and move to the following step.

Once we are done trimming characters from the end of the engraving, we next try to trim characters from the engraving’s beginning. To do this, for an engraving “ABCDE”, we test the following two engravings:

- A"BCDE

- BCDE

Like before, if both of those two engravings are still filtered, then we have eliminated “A”. We reduce our engraving to “BCDE” and iteratively perform the test again, attempting to eliminate the new first character “B”. On any iteration, if either of these two test engravings are not filtered, then we are done iteratively trimming characters from the beginning of the engraving and move to the following step.

Once we are done trimming characters from both sides of the engraving, we next attempt to remove characters from inside of it by testing to see if we can remove all of the six different punctuation and space characters which can be infused inside of a keyword (see the previous section “Keyword infusion rules”). While we could more precisely test removing these punctuation and space characters one at a time at the risk of more testing time, to save time we remove all such punctuation and spaces simultaneously. In all of our testing we only discovered one keyword with such punctuation contained in it, and in the test engraving in which we discovered it all such punctuation was contained in the isolated keyword. Thus, in our testing, this heuristic optimization was always correct.

At this point, we have trimmed all extraneous characters from the end and the beginning of the engraving as well as from inside it, isolating the exact keyword triggering its filtering. However, each of Apple’s keyword filtering rules consist of not just a keyword but also its corresponding wildcard rules which dictate how the keyword filters when appearing inside of an engraving (see the previous section “Keyword wildcard rules”). For example, if POO is the filtered keyword, then is the keyword filtering rule POO, POO*, *POO, or *POO*?

To discover the full filtering rule, we take the isolated keyword and first test whether there is wildcard matching on its right (i.e., whether the rule is POO versus POO*). To do this, we form a new engraving by taking POO and appending “~Q” (a tilde followed by the letter Q) to its end. As appending the “~Q” to the end of an engraving would be unlikely to coincidentally form a different filtered keyword,5 if this new engraving is still filtered, then we conclude that the keyword performs wildcard matching on its right. We perform a similar test prepending “Q~” (the letter Q followed by a tilde) to determine whether the keyword’s filtering rule performs wildcard matching on its left (i.e., whether the rule is POO versus *POO). If the keyword filtering rule performs wildcard matching on both its right and its left, then we conclude that it performs on both sides (i.e., that the rule is *POO*).

Results

We performed this experiment during May and June 2021 from a University of Toronto network. In doing so, we uncovered 1,105 keyword filtering rules across the six regions which we measured. In the remainder of this section, we describe the results of this experiment.

Substitution rules

In analyzing our results we discovered that certain letters in filtered keywords could be consistently substituted with visually similar symbols and that keyword would still be filtered. For instance, in regions where POO is filtered, then so would be PO0, P0O, and P00, i.e., strings where one or more of the O letters were replaced by 0 numbers. In such cases, we do not report POO, PO0, P0O, and P00 as separate filtering rules and instead only report the most idiomatic one (in this case, POO).

We also found that these substitution rules varied according to a keyword’s source language. Rules that we found to generally apply to American English words are as follows:

- Any lowercase letter can be substituted with any uppercase letter and vice versa.

- The letter A can be substituted with @ or Â.

- The letter C can be substituted with the letter K.

- The letter E can be replaced by zero or more letter E’s.

- The letter E can be substituted with the numbers 0 or 3 or with É or Ê.

- The letter N can be replaced by more than one letter N.

- The letter I can be substituted with the number 1 or with Í.

- The letter L can be replaced by more than one letter L.

- The letter L can be substituted with the number 1.

- The letter N can be substituted with Ñ.

- The letter O can be substituted with the number 0 or with Ó.

- The letter S can be substituted with the number 5 or with $.

- The letter U can be substituted with the number 0.

This list of substitution rules is not meant to be exhaustive but merely presents the ones that were evident from our testing.

Since all lowercase letters can be substituted with uppercase letters and vice versa, we only use uppercase letters when describing keyword filtering rules in this report. This convention is also consistent with AirTag engravings, which, unlike iPad engravings, do not allow lowercase letters.

Note that one English language substitution rule is that “E” can be replaced by zero or more “E”’s. Thus, for any keyword for which this substitution rule applies, if any “E” is removed from a filtered engraving then it will still be filtered. For instance, in regions where FREETIBET is a filtered keyword, then the engraving “FRTIBT” would be filtered, as well as “FREEEEEEETIBEEEET”, but not “FEREETIBET”, as there was no “E” originally between the “F” and the “R”.

Note that these rules still apply even in cases that are unintuitive. For instance, in regions where BUTTFACE is a filtered keyword, then the engraving “BUTTFAKE” would also be filtered, even though the “C” in FACE is a soft “C” making an “S” sound phonetically instead of the sound of a “K”. In a real world example of collateral censorship, a Twitter user reported that the engraving “banner” was filtered by Apple. From our results, we know that Apple filters BEANER, a racial slur, and by applying the above substitution rules, we can arrive at “banner” by deleting the first “E” and replacing the “N” with two “N”s.

Some substitution rules consistently applied to French or Chinese latin scripted words (such as Pinyin) but not generally to American English words. Examples of some of these rules are as follows:

- The letter A can be substituted with the number 4.

- The letter I can be replaced by more than one letter I.

- The letter I can be substituted with an exclamation mark (!).

- The letter G can be substituted with the number 9 or with the letter J.

- The letter G can be replaced by more than one letter G.

- The letter S can be replaced by more than one letter S.

- The letter S can be substituted with a dollar sign ($).

- The letter T can be substituted with the number 7.

- The letter U can be substituted with the letter V.

- The letter Z can be replaced with the letter S.

Since substitution rules vary by language, we can use them to help determine which language a keyword is in, even in regions which filter words from multiple languages such as Canada (French and English), when words might be spelled the same in both languages or when one language may contain loan words from another. For instance, since the engravings “NAZI” and “N4S!” are both filtered in Canada, it is likely that it is the French word “NAZI” being filtered, since French substitution rules are allowed.

What types of content are forbidden in each region?

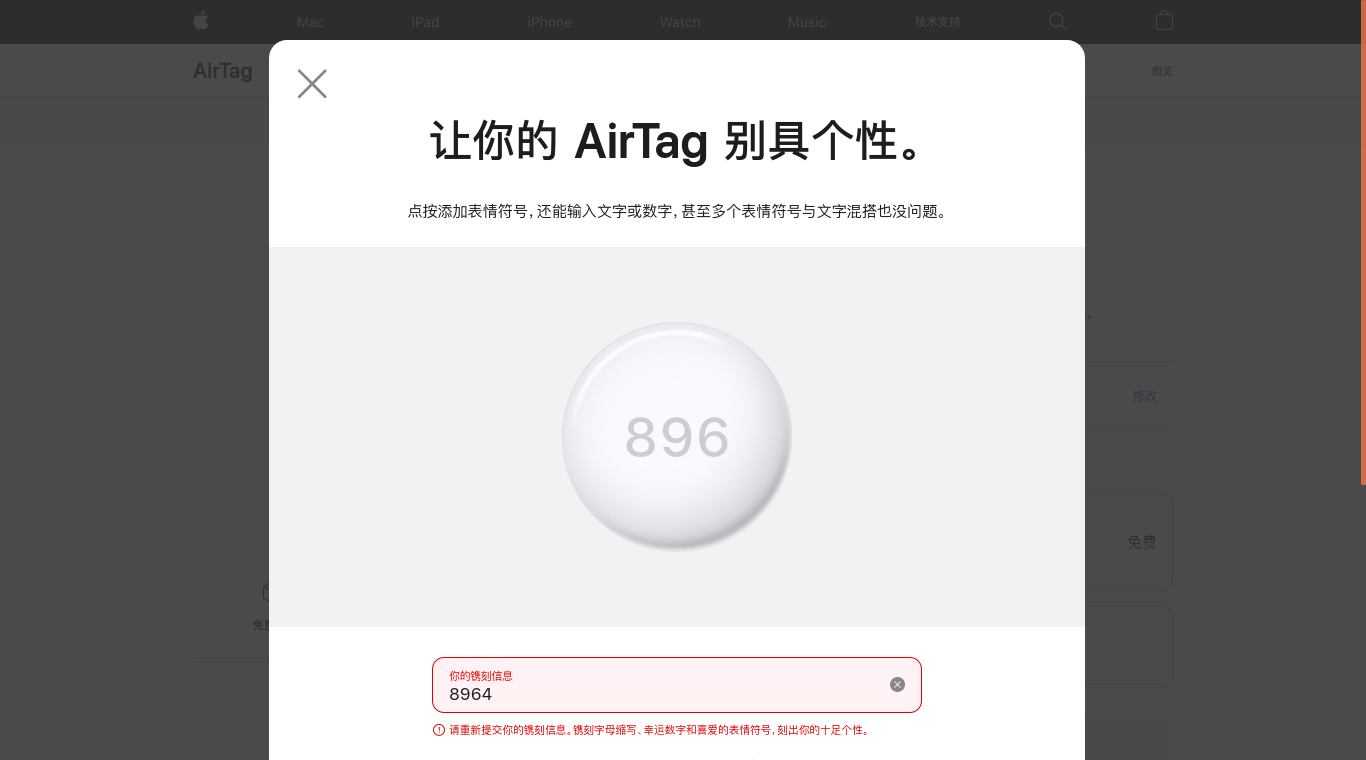

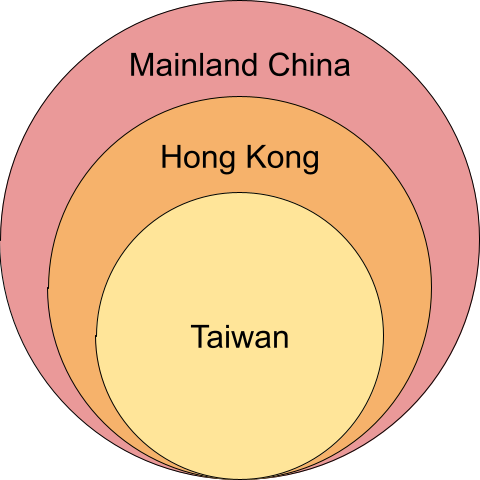

We found that Apple’s keyword filtering of product engravings varies across different regions. Among the keyword filtering rules we discovered in the six regions we tested, the largest number applied to mainland China, where we found 1,045 keywords filtering product engravings, followed by Hong Kong, and then Taiwan (see Figure 5). Compared to its Chinese language filtering, we discovered fewer restrictions on Apple product engravings in Japan, Canada, and the United States.

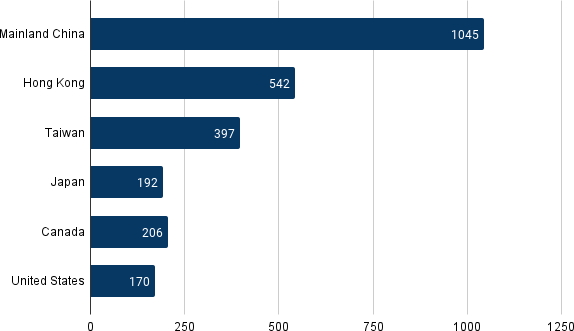

Whereas keyword filtering is present in all regions we tested, we found that a key difference between regions is whether the content targeted by that region’s keyword filtering rules is curtailing certain political discussion versus vulgarity, illicit goods or services, and hate speech. To acquire a better understanding of the context behind each keyword, we categorized all discovered keywords into six content themes based on a codebook we developed in previous work.

We found that across all regions, social content―keywords referencing explicit sexual content, illicit goods and services, or vulgarity—account for the highest portion of filtered content (see Figure 6). However, Apple maintains a nearly as large number of keyword filtering rules targeting certain political topics for its mainland Chinese market, as well as to a lesser extent the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions. We have not found that Apple uses keyword censorship to control political content in the Japan, Canada, or USA regions.

We further set out the content targeted by Apple’s keyword filtering rules in the sections below.

Social

In every region, a plurality of Apple’s keyword filtering rules targeted social content. Keywords in this category include those referencing pornography, profanity, entertainment, gambling, and illicit goods and services. Examples include “百家乐” (Baccarat), “辦文憑” (get a diploma), and “成人电影网” (adult movie net). We found keywords in this category across a variety of languages, including simplified and traditional Chinese, English, French, Spanish, Korean, and Japanese. For example, keywords containing variations of “breast” in different languages are forbidden in all regions we tested, e.g., “유방” (Korean), “乳房” (Chinese), “LOLO” (French), “BOOB” (English). Moreover, a large number of colloquial swear words and verbal insults are targeted by Apple’s keyword filtering (see Table 3).

| Example | Language | Note | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAMN | English | Profanity | All regions tested |

| *ON9* or *ON狗* | Cantonese colloquial | The English word “on” plus “9” or “狗” (both pronounced gau in Cantonese), which, in Cantonese, are homonyms for 戇㞗, a Cantonese slang word for “penis”; a way to call someone stupid, mainly used in Hong Kong | Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan |

| *靠北* or *靠爸* | Taiwanese Hokkien | Literally means someone cries over the death of their father, often used as a profanity cursing the death of someone’s parents in Taiwan | Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan |

| *百姓* | Japanese | Peasant, farmer, country bumpkin | Japan |

Table 3: Selected “social” category keyword filtering rules.

It is unclear how Apple determines which Social terms to block from its products. We noticed that some of the blocked content is fairly broad and benign. For instance, the Chinese term “杂交” (hybrid) is not allowed to be engraved on Apple products in mainland China. Although the term can potentially be derogatory, it is often used in agriculture and biology such as the hybrid rice technologies that the late Chinese scientist Yuan Longping is known for. “全球华人春节联欢晚会” (Global Chinese Spring Festival Gala), a keyword blocked in the mainland Chinese market, shares the same name as the annual entertainment television program hosted by state media China Central Television. A similar focus on socially themed keywords was found in past work on Chinese mobile games and live streaming platforms.

Political

We found that among the six regions we analyzed, Apple censors political content in three regions: mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. In mainland China, a total of 458 keywords (43%) target political content. Such keywords broadly target references to China’s political system, the Communist Party of China, government and party leaders, dissidents, ethnic minority politics, and sensitive events such as the Tiananmen Square Movement and pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong (see Table 4). Among the 458 political keywords Apple censors in mainland China, Apple censors 174 in Hong Kong and 29 in Taiwan.

| Example | Language | Translation | Note | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *人权* | Simplified Chinese | Human rights | Apple broadly censors words related to democracy and human rights in mainland China | Mainland China |

| *達賴* | Traditional Chinese | Dalai | A reference to the Dalai Lama | Mainland China |

| *新聞自由* | Traditional Chinese | Freedom of the press | Apple censors words related to collective action in Hong Kong | Mainland China and Hong Kong |

| *雙普選* | Traditional Chinese | Double Universal suffrage | Universal Suffrage for the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council | Mainland China and Hong Kong |

| *艾未未* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Ai Weiwei | Artist and political dissident | Mainland China and Hong Kong |

| *毛主席* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Chairman Mao | Founder of the Chinese Communist Party | Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan |

| *法輪功* | Traditional Chinese | Falun Gong | Chinese political-religious group | Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan |

Table 4: Selected “political” category keyword filtering rules.

In mainland China, Apple widely censors political speech, including broad references such as 政治 (politics), 抵制 (resist), 民主潮 (wave of democracy), and 人权 (human rights). In mainland China, Apple also heavily censors references to Tibet and Tibetan religion. Such keywords include 正法 (dharma), 達賴 (Dalai), and 达兰萨拉 (Dharamshala). Such heavy-handed censorship restricts users’ abilities to freely express themselves politically and religiously.

In mainland China, Apple also widely censors references to news organizations. Some of these include references to news organizations that are critical of the Chinese Communist Party, such as 美国之音 (Voice of America), a United States funded media organization, or 大纪元 (Epoch Times), an outlet linked to the banned political and religious group Falun Gong. Others include Hong Kong based newspapers such as 南华早报 (South China Morning Post), a paper owned by Alibaba, and 明報 (Ming Pao).

Much of Apple’s political censorship in mainland China also bleeds into Hong Kong. In both regions, Apple broadly censors references to collective action. Such censored keywords include 雨伞革命 (Umbrella Revolution), 香港民运 (Hong Kong Democratic Movement), 雙普選 (double universal suffrage), and 新聞自由 (freedom of the press). In both mainland China and Hong Kong, Apple also censors references to political dissidents such as 余杰 (Yu Jie), 刘霞 (Liu Xia), 封从德 (Feng Congde), and 艾未未 (Ai Weiwei). References such as those to Liu Xia, a poet and wife of Nobel Peace Prize awardee Liu Xiaobo, and to artist Ai Weiwei appear to far exceed Apple’s censorship obligations under Hong Kong’s national security law.

Furthermore, Apple applies political censorship even to Taiwan, a region where the People’s Republic of China has no de facto governance. In Taiwan, in addition to in mainland China and Hong Kong, Apple censors references to the highest-ranking members of the Chinese Communist Party (e.g., 孫春蘭, Sun Chunlan, member of the Party Politburo and Vice Premier of China), historical figures (e.g., 毛主席, Chairman Mao), state organs (e.g., 外交部 , Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Many other keywords are broad references to the political-religious group Falun Gong such as FALUNDAFA and 法輪功 (Falun Gong). There exists no legal obligation for Apple to perform such political censorship in Taiwan.

Notably, Apple seems to update its political censorship with time. Whereas Apple’s censorship of product engravings was reported as far back as 2014, our testing in June 2021 shows that more recent keywords such as 武漢肺炎 (Wuhan pneumonia), a reference to COVID-19, are blocked by Apple in mainland China. Other examples of recently censored terms include 五大诉求 (Five Demands), a 2019 protest slogan in Hong Kong’s recent anti-Extradition Bill movement and 膜蛤 (toad worship), a 2018 cultural phenomenon on the Chinese Internet where users create memes and articles to show their worship towards former Chinese President Jiang Zemin.

People

Similar to content found in other keyword lists on Chinese platforms, we found Apple censored keywords referencing names of individuals in users’ engravings. To distinguish between politically-motivated censorship and censorship of social or unclear contexts, we only include non-political figures and names without clear context in the People category. We found 27 keywords referencing individuals on Apple’s keyword list in the mainland Chinese region.

| Example | Language | Translation | Note | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| *朱文虎* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Zhu Wenhu | Chinese actor | Mainland China |

| *章虹*, *张博涵*, *张博函*, *张搏涵*, *张搏函*, *张桂芳*, *张京生*, *张晓平*, *张星水*, and *张祖桦* | Simplified Chinese | Zhang Hong, Zhang Bohan, Zhang Bohan, Zhang Bohan, Zhang Bohan, Zhang Guifang, Zhang Jingsheng, Zhang Xiaoping, Zhang Xingshui, and Zhang Zuhua. | The “Zhangs”, ten Chinese names all surnamed Zhang, which mostly have unclear political significance. The second through fifth are homonyms. | Mainland China |

Table 5: Selected “people” category keyword filtering rules.

It is unclear how or why these names end up on Apple’s keyword list, many of which appear to be referencing public figures in the entertainment industry. For instance, 朱文虎 (Zhu Wenhu) is likely referencing a National Class-A Performer in China. Born in 1938, Zhu retired from Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company with a high-ranking official title. Other puzzling examples include 张京生 (Zhang Jingsheng), which appears to be the name of Chinese actor who once served in the Chinese military and joined the rescue mission of the 1976 Tangshan earthquake, and 李健 (Li Jian), which could be the name of a Chinese singer and songwriter famous for his song “Legend”.

Many of the keywords referencing people’s names have no clear context. For instance, 章虹 (Zhang Hong) could be the name of a local People’s Procuratorate director in Zhejiang, a deputy director of an urban planning bureau, or an engineering instructor in a Chinese university. Banning these keywords could mean that average individuals with these names would not be able to engrave their name on Apple products in mainland China if they want to.

Racial and ethnic slurs

We found that 28 keywords related to racial or ethnic slurs are forbidden across all six regions (see Table 6).

| Example | Note | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|

| CHINAMAN | Pejorative term referring to a Chinese person, a mainland Chinese national or a person of perceived East Asian race | All regions tested |

| JAP | Ethnic slur referring to Japanese | All regions tested |

| JUNGLEBUNNY | Derogatory term of a black person. | All regions tested |

| WOP | Racial slur for Italians | All regions tested |

| *部落* | Means ぶらく(Buraku), a Japanese term referencing a former, unofficial caste during Japan’s Edo period. People of Buraku were victims of discrimination and ostracism in Japanese society. | Japan |

Table 6: Selected “racial and ethnic slurs” category keyword filtering rules.

Apple inconsistently applies its keyword filtering of racial and ethnic slurs to different regions. For instance, “SLANTEYE”, a derogatory term referencing Asian people, is filtered in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Canada, but not in Japan or the United States. We found that “NAZI” was only filtered in Canada. Highly controversial terms targeting China such as “中國肺炎” (China Pneumonia) or “Chinavirus”, a reference used by former U.S. President Donald Trump inflaming anti-Asian racism, and “CHINAZI”, a phrase invented and defended by some Hong Kong protesters, are filtered only in mainland China, though they are mainly used by people outside the region. Like with Apple’s political censorship, Apple’s filtering of offensive terms appears to be periodically updated, as these terms were born of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Technology

The technology-themed content includes references to identifiers such as names of websites, URLs, and other technology services. We found a total of four technology-related keywords in our testing: one of them triggers blocking in all six regions and three are blocked only in mainland China.

| Example | Translation | Note | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|---|

| NULL | – | In weakly typed applications, the string “NULL” may be confused with the NULL SQL keyword | All regions tested |

| *7GUA* | – | Name of an entertainment website | Mainland China |

| *SNK.NI8.NET* | – | URL of a fan forum of South Korean singer BoA | Mainland China |

| *建联通* | Build China Unicom | Name of a Chinese state-owned telecommunication operator | Mainland China |

Table 7: Selected “technology” category keyword filtering rules.

In previous work, we observed commercially motivated censorship where Chinese platforms blocked references to their competitors or names of products either to prevent users from being lured away or discourage users from criticizing a product. It is possible that 建联通, the keyword referencing China Unicom, one of China’s three state-owned telecommunications operators, was added to Apple’s list due to commercial interests. China Unicom was the earliest Chinese telecommunication company to partner with Apple to bring iPhones to mainland China in 2009.

However, neither the 7GUA nor SNK.NI8.NET websites Apple filters in mainland China appear to be its competitors or have competitor products. These sites have not existed for years.

The filtering of the keyword NULL is likely motivated by the desire to prevent a class of bug in applications where, in a context where the user input was insufficiently strongly typed, the input string “NULL” might be misinterpreted as the SQL keyword NULL. Similar to Apple’s security filtering explained earlier in the “Technical analysis” section, this type of blacklisting is unnecessary and is often insufficient to prevent this type of bug.

Miscellaneous

We categorized keywords with no clear context as miscellaneous content. Seventeen miscellaneous keywords are found blocked in one or more regions in our testing, eight of which are blocked in mainland China only, seven in mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, and two blocked only in Japan.

| Example | Language | Translation | Where filtered |

|---|---|---|---|

| *傻* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Silliness | Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan |

| *掰* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Bye | Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan |

| *有鬼* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Have ghosts | Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan |

| *无赖* | Simplified Chinese | Rogue | Mainland China |

| *祖先* | Simplified or Traditional Chinese | Ancestor | Mainland China |

Table 8: Selected “miscellaneous” category keyword filtering rules.

Table 8 shows examples of Miscellaneous keywords blocked in different regions. Almost all of these keywords are general terms that are seemingly benign in nature, adding further to questions as to how Apple derived their keyword filtering rules.

How did Apple derive each region’s keyword filtering rules?

In this section we investigate how Apple constructed each of the six regions’ lists of keyword filtering rules.

Filtering in Canada versus the United States

One of the findings which we sought to understand is why Apple filters additional content in Canada versus the United States. For instance, we observed that Canada filters SLANTEYE and NAZI, whereas these are not filtered in the United States. Was it Apple’s specific intention that users be able to engrave “NAZI” on their iPads in the United States but not in Canada? We found that our technical analysis can only partially explain the discrepancy in filtering between these two regions.

| Mainland China | Hong Kong | Taiwan | Japan | Canada | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| American English | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| British English | X | X | X | X | ||

| French | X |

Figure 7: For each of three European language sublists, for each of the six regions, whether that language sublist is filtered in that region.

In our analysis, we observed that there were large clusters of filtered keywords that tended to be either all filtered in a region or all not filtered in a region, and the keywords in these clusters appeared related to each other in that they were of the same language. We called such clusters language sublists. In our analysis, we discovered three language sublists, American English, British English, and French, although had we looked at more regions we likely would have discovered others.

We found that the American English sublist appears to filter engravings in all six of the regions we studied, whereas, among the six regions we studied, the British English sublist, which features British slang such as BUGGER or British spelling such as PAEDOPHILE, filters engravings only in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Canada, although we separately tested such keywords in the UK region and found them filtered there as well. Among the six regions we studied, the French language sublist, a list of French keywords, filters engravings only in Canada, but again we separately tested them in the France region and found them filtered there as well.

Returning to the question of why SLANTEYE and NAZI are filtered in Canada, we found that this discrepancy exists because SLANTEYE exists on the British American sublist and NAZI exists on the French language sublist, whereas neither are filtered on the American English sublist. Thus, SLANTEYE and NAZI are filtered in Canada because Canada is filtered by American English, British English, and French language sublists, whereas the United States is only filtered by the American English list.

While this analysis provides a partial explanation for the discrepant filtering, our technical analysis cannot go as far as to explain why SLANTEYE is filtered on the British American sublist but not the American English sublist or why is NAZI filtered on the French language sublist but neither of the English language sublists. Regardless of whether Apple specifically intended it, the end result is the same: SLANTEYE and NAZI are filtered in Canada but not the United States.

While the mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan regions filter American and British English keywords, they also filter a large amount of Chinese content that appears to have been derived in a different fashion than simply the composition of a few language sublists. We explore how Apple derived its filtered Chinese language content in the following sections.

Derivation of mainland China keyword list

Previous research has found that there exists no central list of keywords that the Chinese government compels companies to use to filter content in mainland China. Rather, the keyword blacklists used by companies often have small overlap with each other as each company is tasked with developing their own lists. Nevertheless, large overlap can be observed when lists censor products from the same company or in other cases when list contents may have been derived from another, such as in one instance of a developer forming a new company and using the list from his previous employer. Alternatively, as lists evolve over time, overlap may also occur even if neither of the overlapping lists were directly derived from each other but when one was derived from some ancestor, descendant, or some other evolutionary relative of another. As lists become increasingly available on the Internet such as on GitHub, we can increasingly expect blacklists to be derived from a larger number of sources.

While a high amount of overlap in the keywords censored by two lists suggests either that one list was derived from another or that they otherwise have some common ancestry, we can often more specifically tell whether and which keywords were derived. Specifically, if we, for example, see a long run of 50 keywords in a row shared between lists, then this observation suggests that that sequence of keywords was either copied between lists or that one copied from one of the other’s evolutionary relatives. This is because, while throwing a six-sided die will occasionally yield a six, the probability of throwing 50 six-sided dice and all of them yielding six is astronomically unlikely (1.24 * 10-39). Thus, when we observe a long run of keywords in an older list that are all censored in a newer list, this observation suggests that the newer list either copied these from the older one or from one of its evolutionary relatives.

Even in cases where there exist breaks in the run, if, in an interval of 50 keywords, we see that 47 of them are censored in another list, this observation still strongly suggests that these lists were derived from each other, as it is still astronomically unlikely to throw 50 six-sided dice and have at least 47 of them yield sixes.6 Thus, if we see in an older list a large interval of keywords where the vast majority of them are censored in a newer list, we can similarly conclude that the newer list copied these from the older list or one of its evolutionary relatives. The discrepancies may be due to the newer list removing some keywords or due to the newer list deriving from an ancestor of the older list, where the ancestor had had fewer keywords.

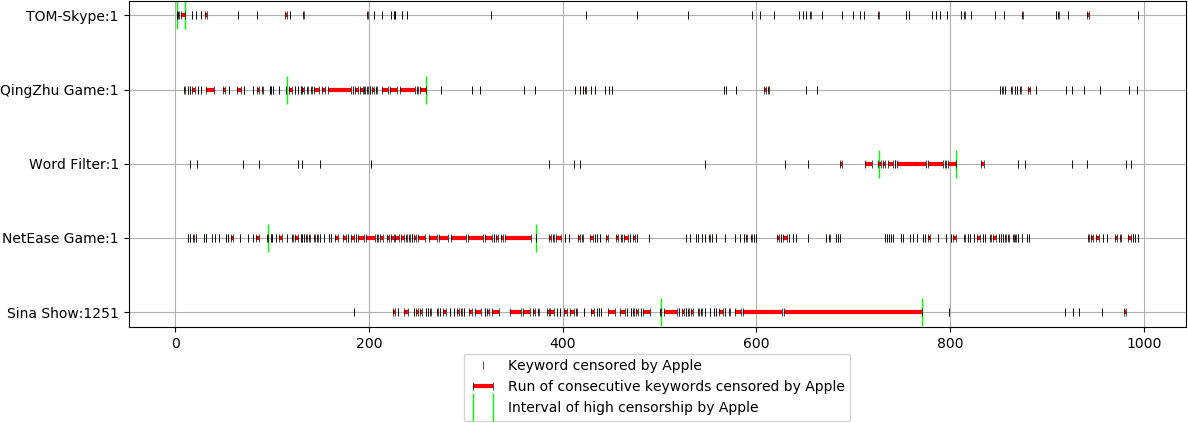

While, as expected, almost all keyword lists in our dataset had very little overlap with Apple’s, we found several keyword lists which did have anomalous sequences of keywords with high overlap with Apple’s list. In Figure 8, we visualize five lists’ overlap with Apple’s list. The first is a TOM-Skype list, a typical list with little overlap, as we would expect to see between two lists with no common ancestry. The other four are (1) a list from QingZhu, a game on GitHub, (2) a list from a dedicated word filtering project on GitHub, (3) a list from a NetEase mobile game, and (4) a list bundled with the Sina Show live streaming software. Each of these four lists have anomalous runs of keywords in common with Apple’s list, as denoted by the red horizontal lines, as well as larger intervals of keywords that have very high overlap with Apple’s list, as delimited by the green vertical bars. These high overlap intervals suggest that Apple’s list was not original and that they derived their list from other sources.

Understanding how Apple’s Chinese filter list was derived helps us to understand the motivation—or lack thereof—behind their censoring of some terms. Some lack of originality in Apple’s list may help explain some of the more perplexing censored keywords discovered, such as the “Zhangs”, ten Chinese names all surnamed Zhang, which mostly have unclear political significance: 章虹 (Zhang Hong), 张博涵 (Zhang Bohan), 张博函 (Zhang Bohan), 张搏涵 (Zhang Bohan), 张搏函 (Zhang Bohan), 张桂芳 (Zhang Guifang), 张京生 (Zhang Jingsheng), 张晓平 (Zhang Xiaoping), 张星水 (Zhang Xingshui), and 张祖桦 (Zhang Zuhua). Moreover, Apple also censors 建联通 (build China Unicom), a seemingly commercially motivated keyword. These keywords appear as part of a much larger interval of keywords in the Sina Show list also censored by Apple, suggesting that Apple’s list is, in part, derived from either Sina Show’s list or some evolutionary relative of it.

As another example, one keyword censored by Apple, SNK.NI8.NET, refers to a site that has not been operational since 2005, and thus Apple would appear to have no motivation censoring it in 2021 and would be unlikely to be aware of its historical existence. However, we found it as part of a long interval of keywords in the NetEase Game list which are almost all censored by Apple. From this interval Apple also censored others, such as 干死GM (fuck game master to death), 干死CS (fuck customer service to death), and 干死客服 (fuck customer service to death). These keywords, targeting the types of complaints that one might make in a game chat against the game’s operator staff, make sense to appear in the list NetEase is using in their game, but make little sense appearing in Apple engravings or being targeted by Apple’s censorship. These findings suggest that Apple’s list is, in part, derived from either NetEase’s list or some common ancestor of it.

Together these and other examples provide evidence that Apple does not fully understand what content they censor. Rather than each censored keyword being born of careful consideration, many seem to have been thoughtlessly reappropriated from other sources.

Derivation of Hong Kong and Taiwan lists

We found that the Taiwan filtering rules are a strict subset of the Hong Kong filtering rules which are a strict subset of the mainland China filtering rules. This relationship between the lists suggests the following two hypotheses as to how Apple created these three rule lists:

-

Apple began with Taiwan’s rules and consecutively added to them to create Hong Kong’s and then mainland China’s lists.

-

Apple began with mainland China’s rules and consecutively removed rules to create Hong Kong and then Taiwan’s lists.

However, our findings disfavor the first hypothesis. First, as discussed in the earlier section, the origin of many keywords in which Apple would have no obvious motivation to censor, such as 干死CS or 干死GM, is most easily explained as being part of large runs of keywords copied from other lists implementing mainland Chinese censorship. We found these and other such keywords censored in Hong Kong and Taiwan as well.

Furthermore, we found that both the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions filter keywords containing certain simplified Chinese characters that are not allowed in either the Hong Kong or Taiwan regions. Thus, the addition of these keyword filtering rules in Hong Kong or Taiwan would serve no instrumental rationality, and it is more likely that they are vestiges from the mainland China list that Apple neglected to remove when adapting the list to the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions, as Apple could have had no rational motivation to ban these words in Hong Kong and Taiwan where their characters were already not allowed.

Apple’s inclusion of an inexplicable amount of mainland Chinese political censorship in the lists used to censor the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions in itself underscores how Apple’s political censorship in mainland China bleeds into the Hong Kong and Taiwan regions. However, the evidence pointing to our second hypothesis suggests something further, that Apple decided what to censor in Hong Kong and Taiwan by using mainland China censorship requirements as a basis from which surrounding regions’ rules were carved out.

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study is that we rely on sample testing to determine which keyword filtering rules are applied in which regions. This limitation is unavoidable as Apple filters engravings server-side, meaning that we cannot directly read each region’s entire list of filtering rules through any sort of reverse engineering. Instead, we submit sample engravings through Apple’s API endpoint and measure which samples are filtered to discover as many as possible. In contrast to server-side filtering, with client-side filtering the filtering occurs in code inside of a downloaded app or, in the case of a Web app such as Apple’s, if Apple had used client-side filtering it would have been inside of Javascript code downloaded and executed by a user’s browser. In cases of client-side filtering, we can read, through reverse engineering, a complete list of filtering rules.

The consequence of this limitation is that there likely exist additional keywords filtered in each region that we were unable to discover using sample testing. Failing to discover some censored keywords in each region may be problematic if the absence of such keywords significantly skews our characterization of Apple’s censorship policies. For instance, we tested a larger number of Chinese keywords than English words, as Chinese keywords made up a larger portion of our test samples. However, we do not believe that this methodological limitation affects the findings of our report for multiple reasons.

First, Chinese keywords make up a larger portion of our test samples because our test samples are based on keyword lists that we have previously reverse engineered from similar censorship systems and because Chinese keywords are disproportionately censored by such similar systems. Additionally, in our work, we found that Apple’s keyword lists may have been directly derived from other keyword lists in our sample set, making this method of sample testing especially appropriate to discover which keywords Apple censors. Moreover, while our work was precipitated by multiple anecdotal observations of Apple’s Chinese political censorship, we are aware of no such reports of, for example, American or Canadian political censorship. Nevertheless, it is important to note that sample testing is useful for revealing what categories of content are censored by a region, but it cannot completely exclude certain categories of content from being filtered by Apple—we may have simply not tested samples that Apple filters.

Questions for Apple

On August 9, 2021, we sent a letter to Apple with questions about Apple’s censorship policies concerning their product engraving service, committing to publishing their response in full. Read the letter here.

Apple sent a response on August 17, 2021. Read their full response here.

Conclusion

Our findings show how Apple, a transnational U.S. company, moderates product engravings across different regions in the world. Whereas Apple’s moderation primarily targets derogatory, sexual, and vulgar content in most regions, the company broadly filters keywords relating to political topics in the China market. The politically-motivated filtering policy is partially exported to its products in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

As companies push to occupy markets globally, they are bound to face a variety of legal and political environments in different jurisdictions. Pressures from governments to moderate content both online and offline are inevitable, as demonstrated by takedown requests documented in corporate transparency reports. Apple’s application of different keyword lists in product engravings across the six regions we analyzed in this report demonstrates the varying legal, political, or social expectations transnational companies face when providing similar products in different jurisdictions.

For companies like Apple, China offers one of the most profitable markets for user acquisition. However, the market also comes with a unique set of challenges due to its legal environment, which ultimately demands that companies find a balance between reaching into China’s domestic market and acquiescing to government pressures and content regulations including those requiring censorship of political speech. Our report shows when it comes to the Chinese market, Apple’s compliance may have exceeded that required by the government’s laws and regulations, a sharp contrast to Apple’s reputation and relationships with law enforcement in the United States. First, Apple widely censors political content in mainland China, including broad references to Chinese leadership, China’s political system, names of dissidents, independent news organizations, and general terms relating to democracy and human rights. Second, Apple not only applies the filtering of mainland Chinese political sensitivity in mainland China but also partially applies it to Hong Kong as well as Taiwan. Although the National Security Law has recently taken effect in Hong Kong, which can potentially be used to mandate entities and individuals to remove political content, freedom of expression is legally protected in the region under the city’s Basic Law and the Bill of Rights. Similarly, freedom of speech is constitutionally protected in Taiwan, a region where the mainland Chinese government does not have de facto governance nor does the region have any legal requirements to moderate political content.

Our review of Apple’s public-facing documents, including its terms of service documents, suggests that Apple has failed to disclose its content moderation policies for product engravings. Additionally, there is no explanation as to who came up with the list of filtered keywords in a given jurisdiction. When moderating engraved content on its products in Canada, for instance, Apple appears to have directly copied from the keyword filtering rules it maintains in the United Kingdom, the United States, and France. As a result, Canadian customers are subject to the combination of three sets of filtered keywords derived from Apple’s other markets. Granted, problematic content such as misleading information, hate speech, racial slurs, and explicit sexual content is proliferating on the Internet, which has prompted some to call for more aggressive content moderation and even speech control. However, even when Apple filters derogatory and discriminatory content, it has failed to explain why certain terms such as “SLANTEYE”, “中國肺炎” (China Pneumonia), or “NAZI” are blocked in some regions but not others. A clear, consistent, and transparent set of guidelines explaining why and how the company moderates content is therefore urgently needed.

The need for Apple to provide transparency in how it decides what content is filtered is especially important as we discovered evidence that Apple derived their Chinese language keyword filtering lists from outside sources, whether copying from others’ lists or receiving them as part of a directive. This evidence would explain why Apple censors websites that predate its engraving service, content originally motivated by anti-competitiveness, and bizarre lists of names with no political salience. This content was found together in other Chinese censorship blacklists, and there would seem to exist no instrumental rationality in Apple censoring it. The existence of these keywords on Apple’s censorship lists suggests that even Apple does not understand what content they censor and that, rather than each censored term being born of careful consideration, many seem to have been thoughtlessly reappropriated from other sources. More troubling is that much of this content derived from other mainland Chinese censorship lists also appears to be used to censor content outside of mainland China, in both Hong Kong and Taiwan. Apple should provide transparency into not just the general categories of content that they censor but also, for all keywords that they censor, Apple should be able to explain why that keyword is censored, including keywords that they reappropriated from outside sources or received as part of a directive.