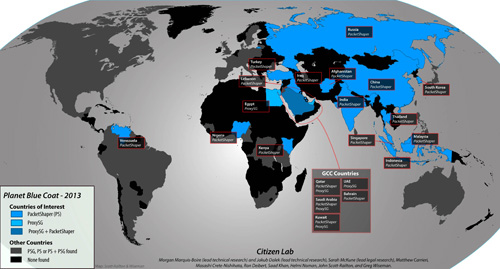

Appendix A

Summary Analysis of Blue Coat “Countries of Interest”

This appendix contains countries of interest in which Blue Coat devices were located.

Read the report: Planet Blue Coat: Mapping Global Censorship and Surveillance Tools.

Countries of interest in which Blue Coat devices were located:

ProxySG

Egypt, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates

PacketShaper

Afghanistan, Bahrain, China, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Kenya, Kuwait, Lebanon, Malaysia, Nigeria, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Singapore, Thailand, Turkey, Venezuela

Bahrain

We identified a single PacketShaper installation flagged by Shodan as recently as December 31, 2012. The address identified by Shodan was on a netblock associated with the Bahrain Internet Exchange (BIX). Additional research using the iplocation.net service and databases provided by db4 and maxmind identify the ISP as “Central Informatics Organisation.” Despite the recent identification by Shodan, this host was not accessible during the verification period in early January 2013. According to its website, BIX is an Internet exchange point that serves “ISPs and the Government Sector in the Kingdom of Bahrain.”1 Privacy International has stated that BIX “may have the capacity to play a role in communications monitoring,” and BIX itself has openly acknowledged that they may monitor ports and connections when “information is required by applicable law.”2 The existence of Blue Coat products on an Internet exchange network suggests a state-level initiative. Bahrain’s extensive censorship regime has only intensified in the wake of the Arab Spring protests. The government actively filters websites critical of the regime, as well as content that is perceived as pornographic, un-Islamic, or accepting of LGBT issues.3 In the past, the Bahraini government has reportedly used web filtering technologies created by Blue Coat Systems and McAfee.4 Bahrain extensively monitors online activity and has used Western-made surveillance software to generate transcripts as part of the interrogation and torture of prisoners.5

Kuwait

We have identified three Blue Coat products present in Kuwait. ProxySG was present on a network belonging to Mada Communications, while the ISPs of Gulfnet and Fast Telco each had a PacketShaper installation present on their networks. These were all initially identified by Shodan and were verified during our testing. Kuwait has targeted blasphemous, LGBT, and perceived un-Islamic content online for censorship.6 The Kuwaiti government has also considered criminalizing the “misuse” of social media, especially with regards to defamation and criticism of government policies, and “allow[ing] government entities to regulate the use of the different new media outlets such as Twitter.”7 In the past, Kuwaiti ISPs have reportedly used SmartFilter and Netsweeper to censor content.8

Qatar

We identified an installation of both ProxySG and PacketShaper on netblocks associated with Qatar Telecom (QTel). Shodan initially identified the PacketShaper installation in late September 2012 and this was verified during testing. The ProxySG installation was initially found as a result of network scanning in October 2012 and verified as accessible in January 2013. A 2011 Wall Street Journal investigation found that Blue Coat technologies have been used in Qatar among other countries in the Gulf.9 Qatar’s censorship regime focuses on websites it considers socially inappropriate, including anti-Islamic, LGBT, and sexual health-related content. Some political websites are also censored.10 According to the U.S. State Department, Qatar censors online content through state-owned ISPs and through proxy servers that monitor chat rooms and email.11 Qatar’s Telecommunications Law punishes those “using a telecommunication network or allowing such use for the purposes of disturbing, irritating or offending any person,” thus giving free reign to authorities to crack down on controversial content.12 Moreover, Chapter 15 of the law requires service providers to comply with government requests for information deemed “necessary for exercising its powers.”13

Saudi Arabia

We were able to identify five total Blue Coat products in Saudi Arabia. There are two installations of the ProxySG product on a network block identified as SaudiNet that was initially detected in mid-2012 by Shodan and verified during testing. Additionally, there are three total PacketShaper installations on the networks identified as ITC, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) and Nournet. Shodan initially identified the installations on KACST and ITC, while a Google search identified the installation on Nournet. Notably, KACST’s Internet Services Unit (ISU) is responsible for implementing the state’s filtering regime.14 Blue Coat Systems has reportedly been present in Saudi Arabia since 2007, when the company announced its intention to expand operations across the region, and has since been open about its relationship with the Saudi government.15 The company cites ISU’s use of ProxySG appliances as a success story, noting that its products allow ISU to “implement flexible policy control over content, users, applications and protocols to protect its users from malicious content.”16 Saudi Arabia’s strict regime of Internet censorship has only intensified following the Arab Spring revolutions and protests in the Middle East and North Africa.17 The government openly acknowledges its engagement in Internet and telecommunications censorship “to block those pages of an offensive or harmful nature to society, and which violate the tenants [sic] of Islamic religion or societal norms.”18 Saudi Arabia has used SmartFilter, now owned by McAfee, to index websites by category and implement mass filtering of content deemed insulting to the political system and offensive to Islamic morals.19

United Arab Emirates

We found five installations of ProxySG on networks in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). All of these installations were on network blocks belonging to the ISP Etisalat. Shodan initially identified one installation on January 1, 2013 while follow up scans around the netblock turned up three additional installations. These installations were accessible during verification but have become sporadically available since their initial verification. Blue Coat Systems maintains a support centre in Dubai’s Internet City (its only known Middle East office) for its regional clients.20 In 2011, the Wall Street Journal reported that the company’s technologies have been used in the UAE, along with a number of other Gulf countries.21 (The same report revealed that one of Blue Coat Systems’ authorized Emirati distributors had sent ProxySG devices to the Syrian regime.22) In the UAE content is blocked pursuant to instructions from the Telecommunications Regulatory Authority (TRA) to ISPs, based on pre-determined content categories. Etisalat, the UAE’s dominant ISP, outlines TRA’s “Prohibited Content Categories” on its website, including content related to pornography, gambling, malicious computer use, circumvention tools, terrorism, and religious hate speech.23 However, the government also filters political websites on an ad hoc basis. Like Kuwait, ISPs in the UAE have used both SmartFilter and NetSweeper to censor content.24 The UAE has made surveillance of cybercafé patrons mandatory by requiring ID and the recording of personal information of users.25

Afghanistan

We identified a single installation of the PacketShaper product on a network identified as an “Afghan Telecom Government Communication” network in Kabul. This was initially identified by Shodan on December 31, 2012 and was accessible during our verification. Pursuant to Afghanistan’s 2005 Telecom Law, monitoring of communication and Internet traffic is permitted when demanded by the Afghanistan Telecom Regulatory Authority, and ISPs must comply with government requests for data in matters of national security.26 In 2010, Afghanistan’s Minister of Information and Culture stated the government’s intent to block websites that promote violence and terrorism, facilitate gambling, deal with “sexual issues,” and associate with drug production and trafficking.27 The government admitted at the time that it did not yet possess the technology to institute website blocking, and reports from the same year indicated that Afghani ISPs were “struggling to enforce” official directives to filter the Internet.28 It is possible that Blue Coat PacketShaper devices that are now employed in the country could have been used to bridge that initial technological gap and build a state-level filtering and surveillance regime from the ground up.

Egypt

We identified a single installation of ProxySG though it was not verified during our testing phase and was inaccessible in follow-up connection attempts. Shodan identified the presence of the product on a network belonging to an Etisalat netblock as recently as October 2012. The IP that Shodan identified resolves to a domain that is associated with the nile-online.net domain. Prior to the 2011 revolution, the Mubarak regime actively monitored social networking platforms, e-mail exchanges, and mobile phone communications.29 In response to the Arab Spring protests of 2011, the government employed a number of techniques to control dissent, including the complete shutdown of Internet access on most ISPs.30 The Mubarak regime also allegedly used Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) tools provided by Narus, a Silicon Valley-based firm and Boeing subsidiary.31 Freedom House reports that the post-Mubarak government has continued to selectively remove controversial content and closely surveil activists and bloggers on Internet and social media.32 In March 2012, for example, the Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technology announced its intention to block pornographic websites from within the country.33 Additionally, Freedom House reports that the Homeland Security Agency allegedly acquired DPI and filtering equipment in 2011.34

Iraq

We identified a single PacketShaper installation that was present on the network of City Telecom, an ISP based in Baghdad. It was identified by Shodan as early as August 2012 and was still accessible during our verification in early January 2013. The current mapping of Blue Coat PacketShaper products in Baghdad coincides with the post-war reconstruction of Iraq’s telecommunications industry and the drafting of legislation specifically tailored to address Internet use. Most recently, the Iraqi government drafted an “Information Crimes Law” that would ostensibly aim to “to provide legal protection for the legitimate use of computers and information networks, and punish those who commit acts that constitute encroachment on the rights of their users,”35 including perpetrators of vaguely defined “prohibited activities” such as harming the “reputation of the country,” broadcasting “false or misleading facts,” and violating “religious, moral, family, or social values.”36 The law also sets out penalties for ISPs that fail to comply with government requests for user data.37 As of December 2012, parliament has reportedly placed the Information Crimes Law on hold.38 However, the deployment of Blue Coat PacketShaper devices, in conjunction with legislation that permits the monitoring and prosecution of Internet users, indicates possible ‘surveillance by design’ in the context of post-conflict reconstruction.

Lebanon

We identified two installations of PacketShaper during the course of research. One installation was identified initially by Shodan on December 12, 2012. This installation was found on a netblock associated with “IncoNet Data Management.” An additional PacketShaper installation was identified by a Google search on a netblock associated with “Virtual ISP Lebanon” (visp). Tests performed in 2009 indicated no known state-level Internet filtration or surveillance in Lebanon.39 Since 2010, however, Lebanese authorities have detained many citizens for criticizing the government and army.40 Most recently, the Lebanese Ministry of Information has drafted a new law prohibiting the publication of online content deemed offensive to “public morals.”41

Turkey

We identified a single installation of PacketShaper that was identified by a Google search in early 2013. This was on a netblock associated with TTNet, Turkey’s largest ISP and a subsidiary of the formerly state-owned Turk Telecom.42 Blue Coat Systems expanded its presence in the country in 2008 by adding a number of Turkish distributors “to better serve Turkish companies and organizations.”43 One reseller, Innova, reportedly sought to combine “its technical expertise and reputation in the market with Blue Coat ProxySG appliances to provide organizations with tools they need to gain control over the appliances on their networks.”44 Freedom House reports that, since 2001, Turkey has passed a series of laws that collectively empower state organizations to filter content.45 Law No. 5651 — “Regulation of Publications on the Internet and Suppression of Crimes Committed by Means of Such Publication” — ostensibly seeks to prevent youths from accessing illicit content such as pornography and gambling. However, that regulation and other laws have been applied more broadly to block political content such as criticism of Kemal Ataturk, news sources, and media sharing websites.46 In November 2011, the Turkish government instituted a national filtering system that requires ISPs to offer customers the option to block content deemed inappropriate for families and children.47 Engelli Web, a Turkish website that tracks censored content, lists over 22,000 blocked websites as of January 14, 2013.48

Russia

We identified a single installation of the PacketShaper product on a netblock associated with the Vimpelcom ISP. This was initially identified by Shodan on December 30, 2012 and was verified during testing. A high level of state control over the domestic telecommunications market exists in Russia.49 Recently, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev signed a new law “blacklisting” sites the government views as fronts for illegal content.50 Roskomnadzor — Russia’s federal service for monitoring mass media compliance — has introduced Deep Packet Inspection “on a nationwide scale,”51 having previously announced a competitive “contest” for software designed to monitor sites for “extremist” content.52 Russia’s Soviet-era system to intercept phone traffic has also undergone recent upgrades.53 One of the largest providers in the region, Mobile TeleSystems OJSC (MTS), has used Blue Coat in the past at the Internet gateway of MTS’s headquarters in Moscow to protect against “Internet threats.”54 It is reasonable to surmise that other telecoms in Russia are using Blue Coat for the same purposes; however, as Russia seems to be increasing surveillance of online content, the use of foreign technology for political purposes must be monitored in the future.

China

We identified three installations of Blue Coat products present on the netblock associated with ChinaNet. Two were identified by Shodan initially in late 2012 and verified during testing. One additional installation of PacketShaper was found through a Google search. This installation had a system name of “WT-CHENGDU-INT-PS” and was present on a ChinaNet IP in Sichuan. ChinaNet is an “operational brand” of state-owned China Telecom and is described as “the world’s largest Internet network.”55 China’s Internet filtering and surveillance regime, often referred to as the “Great Firewall,” is pervasive and multifaceted. The government employs a variety of means to prevent citizens from accessing material that is deemed politically threatening or socially controversial, including “tight regulations on domestic media, delegated liability for online content providers, just-in-time filtering, and ‘cleanup’ campaigns.”56 Deep Packet Inspection technology is used to blacklist pages based on pre-defined keywords, as well as to monitor users’ Internet activity.57 Moreover, thousands of government and private sector workers reportedly monitor and censor objectionable content on social media platforms, blogs, and political websites.58 Chinese legislation holds Internet information service providers accountable for content on their servers and specifies nine forbidden content categories, including material that opposes constitutional principles, threatens national security and the state, or “undermines social stability.”59

South Korea

There were three installations of PacketShaper identified on netblocks associated with Korea Telecom. All three installations were initially identified by Shodan in December 2012. These were verified as accessible, though some of these have been sporadically available since verification. South Korea’s government imposes more constraints on online speech than most democratic countries. While the rate of filtering is generally low, online content and expression is heavily regulated through legal and technical measures.60 ISPs target social content, and content related to conflict and security — especially content that is pro-North Korea or considered threatening to national security.61 The Korea Communications Standards Commission is authorized to order the blocking or closure of websites, the deletion of messages, and the suspension of users, as well as to mediate online defamation disputes.62 Although the Constitutional Court recently ruled a five-year-old online real-name registration rule to be unconstitutional, concerns over government surveillance remain.63 In 2012, Freedom House reported that the government has increased purchases of interception equipment and documented instances where authorities have not followed protocol when obtaining information on citizens.64 For instance, a scandal emerged in 2012 over unlawful surveillance activities by the Civil Service Ethics Division, a division established in 2008 for the purposes of monitoring corruption amongst government officials. The Korean Broadcasting System released over 2,600 records documenting the illegal surveillance of civilians known to be critical of the government, such as labour union leaders and journalists.65 In 2010, seven members of the Division were convicted for illegal surveillance of citizens.66

Indonesia

A single installation of PacketShaper was identified by a Google search. This installation was present on a netblock associated with the Lintasarta ISP. ISPs in Indonesia are subject to filtering requests from the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology.67 Indonesian Internet filtering heavily targets pornographic Web sites. Several ISPs also blocked some sex education and LGBT content, as well as sites offering circumvention tools. However, testing revealed that filtering was unsystematic and inconsistent, as demonstrated by differences across ISPs.68 The government has occasionally blocked anti-Islamic content.69

Malaysia

We identified three PacketShaper installations in Malaysia during research. Two installations were initially identified by Shodan in late 2012 and subsequently verified. They were present on netblocks associated with Jaring and TMNet. They have since been sporadically accessible. There was an additional installation identified by a Google search in early 2013 on a netblock associated with the Arcnet ISP. Blue Coat Systems maintains a physical presence in the country, with its Asia Pacific Headquarters located in Kuala Lumpur. While there is no evidence of technical Internet filtering in Malaysia, online content is regulated through other means.70 The Communications and Multimedia Act (1998) prohibits online content that is “indecent, obscene, false, menacing, or offensive in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass any person.”71 The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission, which is responsible for regulating the Internet, is known for tracking online discussions and asking content creators to remove such content.72 Freedom House has expressed concern that authorities seem to be capable of identifying anonymous Internet and mobile users with the help of service providers.73 In April 2012, the government passed the Security Offenses (Special Measures) Act, which authorizes the interception of communications without a judicial order in cases of vaguely defined security offences.74

Singapore

During research, we identified two installations of PacketShaper in Singapore. One was initially identified by Shodan in mid-2012 and verified on a netblock associated with SingNet. This installation has been sporadically accessible since verification. An additional installation was found by a Google search on a netblock associated with the ViewQwest ISP. Singapore engages in minimal Internet filtering by blocking only a small set of high-profile pornographic Web sites, suggesting that filtering is imposed for symbolic, rather than preventative, purposes.75 Rather than employing technical measures to control online content, the government utilizes licensing controls as well as legal pressures, such as defamation suits.76 All ISPs offer content filtering services for residential broadband subscribers.77 A 2006 Privacy International report found that Singaporean law permits government surveillance of Internet activity and “grants law enforcement broad power to access data and encrypted material when conducting an investigation.”78

Thailand

A single PacketShaper installation was identified by Shodan in late 2012, which was verified as accessible. This installation was present on a netblock associated with the ISP CS Loxinfo, which provides home and business Internet service. Thailand primarily blocks sites related to political opposition, pornography, online gambling, and circumvention tools.79 A central focus of blocking is lèse-majesté content.80 Lèse-majesté refers to punishment for any negative critical remarks about the monarchy and is strictly enforced through provisions in the Penal Code. Internet filtering in Thailand is governed by the Computer Crime Act (2007), which authorizes the prosecution of Internet intermediaries for “intentionally supporting or consenting for crimes linked to the use of computers,” effectively making Internet intermediaries legally responsible for policing lèse-majesté content.81 There has been some concern over indications that the Thai government intends to increase its capacity to intercept private communications.82 For example, in December 2011, Thai authorities introduced a proposal for purchasing a four million baht lawful interception system for the purposes of cracking down on online lèse-majesté content.83

India

We identified four PacketShaper installations present in India. These installations were all initially identified by Shodan in late 2012 and verified as accessible. They were present on netblocks associated with the ISPs of Bharti Airtel, Reliance, and Tata Communications, all of which have been implicated in filtering to some degree. In July 2012, Citizen Lab found that websites in Omani cyberspace were being inadvertently filtered as a result of a traffic peering arrangement between Bharti Airtel and Omani ISP Omantel.84 Reliance Communications was one of several ISPs to block file-sharing sites,85 while Tata Communications has reportedly used Netsweeper for filtering.86 India engages in selective filtering in many categories, including politically “extremist” websites.87 Despite its commitment to free expression, amendments to the country’s Information Technology Act (ITA) in 2008 have been criticized as overly broad. Section 66A, for example, criminalizes the sending of “offensive messages” through telecommunications services without clarifying what constitutes “offensive.”88 Moreover, Section 69 of the ITA authorizes government agencies to monitor and intercept Internet traffic and user information for purposes of national security or cyber security.89

Kenya

There were three PacketShaper installations found in Kenya during research. All three were initially identified by Shodan in December 2012 and were verified as accessible. These were on netblocks associated with Hughes Network Systems, which is a satellite-based Internet provider. The hostnames of the IP addresses of these installations resolve to the iWayAfrica domain, which is an African provider of broadband Internet service. In 2012, it was reported that the Communications Commission of Kenya was implementing a system to monitor incoming and outgoing traffic on the country’s networks, including personal e-mails, in order to respond to potential cyber threats. Mobile operators were instructed to cooperate in the installation of Internet traffic monitoring equipment known as Network Early Warning Systems.90

Nigeria

During research there were two PacketShaper installations found on networks in Nigeria. One was identified by Shodan during mid-2012 and was verified as accessible. This installation was present on a netblock associated with the IPNX ISP, and had a system name of “IPNX_SHAPER” set on the login screen. There was an additional installation on a netblock associated with Cobranet. (Note that in the data provided, the installation is listed as a Lebanese IP address because the ISP operating in Nigeria is of Lebanese ownership, as seen in the whois record for cobranet.org.) No evidence of filtering has been found in Nigeria in the past.91 It has been reported that some ISPs block access when users are found to be downloading copyrighted content. Freedom House states that this is done not to protect intellectual property but to manage network traffic.92

Venezuela

We identified a single installation of PacketShaper on a netblock belonging to CANTV Servicios, one of the country’s largest telecommunications providers and a state-owned enterprise.93 This was identified by Shodan in August 2012 and was verified during testing. There is no current evidence of filtering of political or social sites in Venezuela.94 However, Reporters Without Borders has expressed concern that the lack of extensive Internet censorship in the country ignores other methods of controlling Venezuelan cyberspace, such as the monitoring of Internet forums and websites for politically sensitive content.95

Footnotes

1“FAQ,” Bahrain Internet Exchange, http://www.bix.bh/faq_general.php.

2https://www.privacyinternational.org/reports/surveillance-briefing-bahrain/surveillance-in-practice; and “Memorandum of Understanding (MoU),” Bahrain Internet Exchange, http://www.bix.bh/mou.php.

3“Bahrain,” OpenNet Initiative, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/bahrain.

4Paul Sonne and Steve Stecklow. “U.S. Products Help Block Mideast Web.” Wall Street Journal, March 27, 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704438104576219190417124226.html

5“Freedom on the Net 2012: Bahrain,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/bahrain#_ftn8; and Ben Elgin and Vernon Silver, “Torture in Bahrain Becomes Routine With Help From Nokia Siemens,” Bloomberg, August 22, 2011, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-08-22/torture-in-bahrain-becomes-routine-with-help-from-nokia-siemens-networking.html.

6“Kuwait,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/kuwait.

7Kevin Collier, “Kuwait moves toward criminalizing online dissent,” The Daily Dot, August 16, 2012, http://www.dailydot.com/news/kuwait-social-media-dissent-law/.

8Helmi Noman and Jillian C. York, “West Censoring East: The Use of Western Technologies by Middle East Censors, 2010-2011, March 2011, http://opennet.net/west-censoring-east-the-use-western-technologies-middle-east-censors-2010-2011; and Helmi Noman “When a Canadian Company Decides What Citizens in the Middle East Can Access Online,” OpenNet Initiative, May 16, 2011, http://opennet.net/blog/2011/05/when-a-canadian-company-decides-what-citizens-middle-east-can-access-online.

9Malas et al., “U.S. Firm Acknowledge Syria Uses Its Gear to Block Web.” http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970203687504577001911398596328.html

10“Qatar,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/qatar.

11“Qatar,” U.S. Department of State Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, March 11, 2008, http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2007/100604.htm

12Telecommunications Law of the State of Qatar. Unofficial English translation available at http://www.ictqatar.qa/sites/default/files/documents/telecom%20law%202006.pdf.

13Ibid.

14King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Internet Services Unit, “Introduction to Content Filtering,” http://www.isu.net.sa/saudi-internet/contenet-filtring/filtring.htm.

15“Blue Coat expansion in region touches Saudi Arabia and Egypt,” AMEinfo.com, August 15, 2007, http://www.ameinfo.com/129219.html.

16“KACST Deploys Blue Coat Appliances to Provide Secure and Productive Web Access in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” Blue Coat Systems, http://www.bluecoat.com/company/customers/kacst-deploys-blue-coat-appliances-provide-secure-and-productive-web-access.

17“Freedom on the Net 2012: Saudi Arabia,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/saudi-arabia.

18“Introduction to Content Filtering,” King Abdulaziz City for SCience and Technology Internet Services Unit, http://www.isu.net.sa/saudi-internet/contenet-filtring/filtring.htm.

19“Saudi Arabia,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/saudi-arabia; and Noman and York, “West Censoring East.”

20“Company,” Blue Coat Systems, http://www.bluecoat.com/company.

21Malas et al., “U.S. Firm Acknowledges Syria Uses Its Gear to Block Web.”

22See William McQuillen, “U.S. Bans UAE Company for Supplying Internet Filter to Syria,” Bloomberg, December 15, 2011, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-12-15/u-s-bans-uae-company-for-supplying-internet-filter-to-syria.html.

23“Prohibited Content Categories,” Etisalat, http://www.etisalat.ae/assets/document/blockcontent.pdf.

24Helmi Noman, “A Blind-date with the Censors in UAE,” OpenNet Initiative, June 20, 2008, http://opennet.net/blog/2008/06/a-blind-date-with-censors-uae; and Noman and York, “West Censoring East.”

25“Countries Under Surveillance: United Arab Emirates,” Reporters Without Borders, http://en.rsf.org/surveillance-united-arab-emirates,39760.html.

26“Afghanistan,” OpenNet Initiative, May 8, 2007, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/afghanistan.

27Susan J. Campbell, “Afghan Government Plans to Ban Certain Internet Sites, Denies Censorship,” TMCnews, March 4, 2010, http://ipcommunications.tmcnet.com/topics/ip-communications/articles/77614-afghan-government-plans-ban-certa-internet-sites-denies.htm.

28“Internet Censorship in Afghanistan,” The World, March 24, 2010, http://www.theworld.org/2010/03/internet-censorship-in-afghanistan-2/; and Danny O’Brien and Bob Dietz, “Using New Internet Filters, Afghanistan Blocks News Site,” Yahoo! Business and Human Rights Program, October 6, 2010, http://www.yhumanrightsblog.com/blog/2010/10/12/using-new-internet-filters-afghanistan-blocks-news-site/.

29“Egypt,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/egypt.

30Iljitsch van Bejnum, “How Egypt Did (And Your Government Could) Shut Down the Internet,” Ars Technica, January 30, 2011, http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2011/01/how-egypt-or-how-your-government-could-shut-down-the-internet.

31Timothy Karr, “One U.S. Corporation’s Role in Egypt’s Brutal Crackdown,” Huffington Post, January 28, 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/timothy-karr/one-us-corporations-role-_b_815281.html; and “Telecom Egypt Selects Narus for Traffic Anomaly Detectionl Telecom Egypt Leverages Narus’ Security Expertise to Protect Financial Service Data,” Business Wire, February 23, 2005, http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Telecom+Egypt+Selects+Narus+for+Traffic+Anomaly+Detection;+Telecom…-a0129070647.

32“Freedom on the Net 2012: Egypt,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/egypt.

33“Blocking Internet Pornography A Priority for Telecom Minister,” Egypt Independent, March 22, 2012, http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/blocking-internet-pornography-priority-telecom-minister.

34“Freedom on the Net 2012: Egypt.”

35“Iraq’s Information Crimes Law: Badly Written Provisions and Draconian Punishments Violate Due Process and Free Speech,” Human Rights Watch, July 12, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/iraq0712webwcover.pdf.

36Danny O’Brien, “Iraqi Cybercrime Bill is the Worst Kind,” Committee to Protect Journalists, March 30, 2012, http://cpj.org/internet/2012/03/iraqi-cybercrime-bill-is-the-worst-kind.php.

37“Iraq’s Information Technology Crimes Act of 2011: Vague, Overbroad, and Overly Harsh,” Access, April 2012, https://s3.amazonaws.com/access.3cdn.net/fa4f8b344e40e560c3_pum6ib7e1.pdf.

38Laith Hammoudi, “Tough “Cybercrimes Bill” on Hold in Iraq,” Institute for War and Peace Reporting, December 24, 2012, http://iwpr.net/report-news/tough-cybercrimes-bill-hold-iraq.

39“Lebanon,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/lebanon.

40Josh Wood, “Lebanon Cracks Down on Internet Freedom,” New York Times, November 3, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/04/world/middleeast/04iht-m04m1leblog.html?_r=0.

41Khodor Salameh, “Lebanese Internet Law Attacks Last Free Space of Expression,” Al Akhbar, March 9, 2012, http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/4997.

42“Turk Telecom Announces Re-shuffle,” TMTFinance.com, July 9, 2012, http://www.tmtfinance.com/news/turk-telecom-announces-re-shuffle.

43“Blue Coat Expands Presence in Turkey with Leading Distributor,” The Content Factory, September 15, 2008, http://www.tcf-me.com/client_portal/26/news_releases/1004364240.

44“Blue Coat Partners with Turkey’s Innova to Extend Regional Presence,” Al Bawaba, October 21, 2008, http://www.albawaba.com/news/blue-coat-partners-turkey%E2%80%99s-innova-extend-regional-presence.

45“Freedom on the Net 2011: Turkey,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/turkey.

46“Turkey,” OpenNet Initiative,” http://opennet.net/research/profiles/turkey; and “Freedom on the Net 2012: Turkey.”

47“New Internet Filtering System Condemned As Backdoor Censorship,” Reporters Without Borders, December 2, 2011, http://en.rsf.org/turquie-new-internet-filtering-system-02-12-2011,41498.html.

48“Categories,” Engelli Web, http://engelliweb.com/kategoriler/.

49“Russia,” OpenNet Initiative, December 19, 2010, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/russia.

50Reuven Cohen, “Russia Passes Far Reaching Internet Censorship Law Targeting Bloggers and Journalists,” Forbes, November 1, 2012, http://www.forbes.com/sites/reuvencohen/2012/11/01/russia-passes-far-reaching-internet-censorship-law-targeting-bloggers-journalists/.

51Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan,“The Kremlin’s New Internet Surveilance Plan Goes Live Today,” Wired, November 1, 2012, http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/11/russia-surveillance/all/.

52“Danger of Generalized Online Surveillance and Censorship,” Reporters Without Borders, March 30, 2011, http://en.rsf.org/russia-danger-of-generalized-online-30-03-2011,39910.html.

53Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, “In Ex-Soviet States, Russian Spy Tech Still Watches You,” December 21, 2012, http://www.wired.com/dangerroom/2012/12/russias-hand/all/.

54“Mobile TeleSystems OJSC Uses Blue Coat Appliances to Protect Employees from Internet Threats,” Blue Coat, http://bluecoat.com/company/customers/mobile-telesystems-ojsc-uses-blue-coat-appliances-protect-employees-internet.

55“Company Overview 2009,” China Telecom, http://en.chinatelecom.com.cn/corp; and “ChinaNet,” China Telecom, http://en.chinatelecom.com.cn/products/t20060116_48406.html.

56“China,” OpenNet Initiative, August 9, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/china.

57Ben Wagner, “Study: Deep Packet Inspection and Internet Censorship,” Global Voices Advocacy, June 25, 2009, http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/2009/06/25/study-deep-packet-inspection-and-internet-censorship/; and “Freedom on the Net 2012: China,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/china.

58“Freedom on the Net 2012: China.”

59“Measures for Managing Internet Information Services,” China Culture, http://www.chinaculture.org/gb/en_aboutchina/2003-09/24/content_23369.htm.

60See: “South Korea,” OpenNet Initiative, August 6, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/south-korea.

61Ibid.

62Ibid.

63The Online Verification Law was introduced in 2007 in order to reduce abusive behaviour online, such as spreading false rumours. See Choe Sang-Hun, “South Korean Court Rejects Online Name Verification Law,” New York Times, August 23, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/24/world/asia/south-korean-court-overturns-online-name-verification-law.html.

64“Freedom on the Net 2012: South Korea,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/south-korea.

65“Surveillance Case Ripped Wide Open,” Korea Joongang Daily, March 31, 2012, http://koreajoongangdaily.joinsmsn.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=2950775.

66Choe Sang-Hun, “In South Korea Scandal, Echoes of Watergate,” New York Times, April 9, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/10/world/asia/government-spying-charges-complicate-korean-vote.html?pagewanted=all.

67“Brief Paper: “Internet Freedom at Indonesia,” Best Bits, August 2012, http://bestbits.igf-online.net/wp-uploads/2012/10/internet-freedom-indonesia.pdf.

68“Indonesia,” OpenNet Initiative, August 9, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/indonesia.

69Melody Zhang, “Indonesia Increases Censorship for Ramadan,” Herdict Blog, July 30, 2012, http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/herdict/2012/07/30/indonesia-increases-censorship-for-ramadan; and “Internet Cafes Given a Month to Block Porn Websites,” Jakarta Post, August 2, 2010, http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2010/08/02/internet-cafes-given-a-month-block-porn-websites.html-0.

70 “Freedom on the Net 2012: Malaysia,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/malaysia.

71Section 211, Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Act, 1998.

72“Freedom on the Net 2012: Malaysia.”

73“Freedom on the Net 2012: Malaysia.”

74“Malaysia: Security Bill Threatens Basic Liberties,” Human Rights Watch, April 10, 2012, http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/04/10/malaysia-security-bill-threatens-basic-liberties.

75“Singapore,” OpenNet Initiative, May 10, 2007, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/singapore.

76See Ibid.

77“S’pore ISPs to Actively Promote Internet Filters,” Yahoo News, July 15, 2011, http://sg.news.yahoo.com/blogs/fit-to-post-technology/pore-isps-told-promote-mobile-internet-filters-052641650.html.

7Privacy International, “Chapter II. Surveillance Policy,” Singapore, December 12, 2006, https://www.privacyinternational.org/reports/singapore/ii-surveillance-policy.

79“Thailand,” OpenNet Initiative, August 7, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/thailand.

80“Freedom on the Net 2012: Thailand,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/thailand.

81Kieran Bergmann, “Outsourcing Censorship,” Open Canada, Kieran Bergmann, http://opencanada.org/features/the-think-tank/essays/outsourcing-censorship/.

8“Freedom on the Net 2012: Thailand.”

8“Web Censor System Hits Protest Firewall,” Bangkok Post, December 15, 2011, http://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/learning-from-news/270926/new-web-censorship-worries.

8“Routing Gone Wild: Documenting Upstream Filtering in Oman via India,” Citizen Lab, July 12, 2012, https://citizenlab.ca/2012/07/routing-gone-wild/.

85Rajini Vaidyanathan, “Hacking Group Anonymous Takes on India Internet ‘Censorship,'” BBC, June 9, 2012, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-18371297.

86Noman and York, “West Censors East.”

87“India,” OpenNet Initiative, August 9, 2012, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/india.

88“Breaking Down Section 66A of the IT Act,” The Centre for Internet & Society, November 25, 2012, http://cis-india.org/internet-governance/blog/breaking-down-section-66-a-of-the-it-act.

89Information Technology (Amendment) Act 2008, http://deity.gov.in/sites/upload_files/dit/files/downloads/itact2000/it_amendment_act2008.pdf

90Okuttah Mark, “CCK Sparks Row with Fresh Bid to Spy on Internet Users,” Business Daily, March 20, 2012, http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/Corporate-News/CCK-sparks-row-with-fresh-bid-to-spy-on-Internet-users-/-/539550/1370218/-/item/2/-/edcfmqz/-/index.html; and Winfred Kagwe, “Kenya: CCK Defends Plan to Monitor Private Emails,” All Africa, May 17, 2012, http://allafrica.com/stories/201205181170.html.

91“Nigeria,” OpenNet Initiative, October 1, 2009, http://opennet.net/research/profiles/nigeria.

92“Freedom on the Net 2012: Nigeria,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/nigeria#_ftn1.

93“Venezuela’s CANTV: What Should a 21st Century “Socialist” Telecommunications Company Look Like?” Venezuela Analysis, March 15, 2010, http://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/5189.

94“Freedom on the Net 2012: Venezuela,” Freedom House, http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2012/venezuela.

95“Venezuela,” Reporters Without Borders, http://en.rsf.org/surveillance-venezuela,39770.html.