The Great iPwn

Journalists Hacked with Suspected NSO Group iMessage ‘Zero-Click’ Exploit

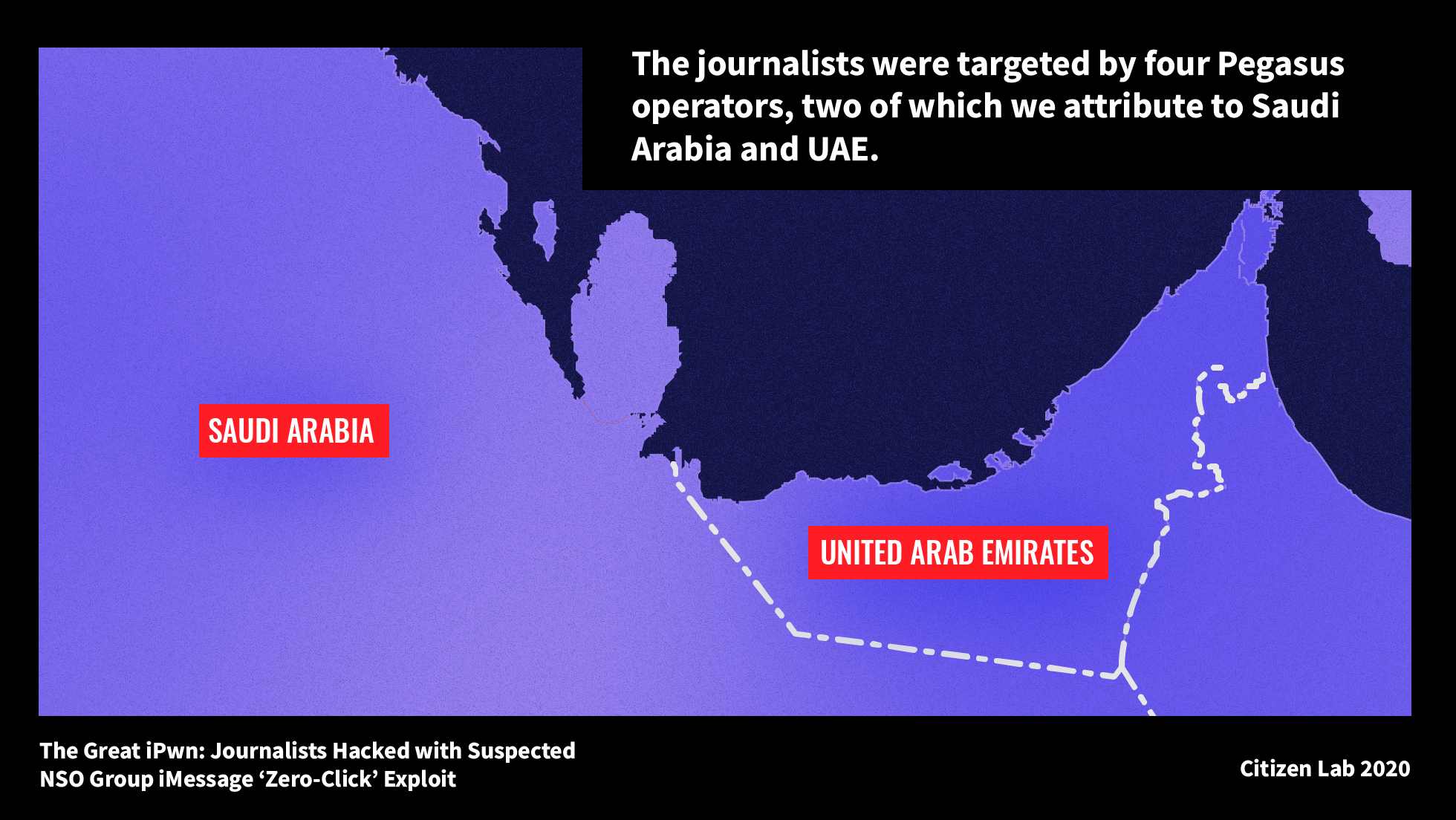

Government operatives used NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware to hack 36 personal phones belonging to journalists, producers, anchors, and executives at Al Jazeera. The journalists were hacked by four Pegasus operators, including one operator MONARCHY that we attribute to Saudi Arabia, and one operator SNEAKY KESTREL that we attribute to the United Arab Emirates.

Summary & Key Findings

- In July and August 2020, government operatives used NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware to hack 36 personal phones belonging to journalists, producers, anchors, and executives at Al Jazeera. The personal phone of a journalist at London-based Al Araby TV was also hacked.

- The phones were compromised using an exploit chain that we call KISMET, which appears to involve an invisible zero-click exploit in iMessage. In July 2020, KISMET was a zero-day against at least iOS 13.5.1 and could hack Apple’s then-latest iPhone 11.

- Based on logs from compromised phones, we believe that NSO Group customers also successfully deployed KISMET or a related zero-click, zero-day exploit between October and December 2019.

- The journalists were hacked by four Pegasus operators, including one operator MONARCHY that we attribute to Saudi Arabia, and one operator SNEAKY KESTREL that we attribute to the United Arab Emirates.

- We do not believe that KISMET works against iOS 14 and above, which includes new security protections. All iOS device owners should immediately update to the latest version of the operating system.

- Given the global reach of NSO Group’s customer base and the apparent vulnerability of almost all iPhone devices prior to the iOS 14 update, we suspect that the infections that we observed were a miniscule fraction of the total attacks leveraging this exploit.

- Infrastructure used in these attacks included servers in Germany, France, UK, and Italy using cloud providers Aruba, Choopa, CloudSigma, and DigitalOcean.

- We have shared our findings with Apple and they have confirmed to us they are looking into the issue.

1. Background

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware is a mobile phone surveillance solution that enables customers to remotely exploit and monitor devices. The company is a prolific seller of surveillance technology to governments around the world, and its products have been regularly linked to surveillance abuses.

Pegasus became known for the telltale malicious links sent to targets via SMS for many years. This method was used by NSO Group customers to target Ahmed Mansoor, dozens of members of civil society in Mexico, and political dissidents targeted by Saudi Arabia, among others. The use of malicious links in SMSes made it possible for investigators and targets to quickly identify evidence of past targeting. Targets could not only notice these suspicious messages, but they could also search their message history to detect evidence of hacking attempts.

More recently, NSO Group is shifting towards zero-click exploits and network-based attacks that allow its government clients to break into phones without any interaction from the target, and without leaving any visible traces. The 2019 WhatsApp breach, where at least 1,400 phones were targeted via an exploit sent through a missed voice call, is one example of such a shift. Fortunately, in this case, WhatsApp notified targets. However, it is more challenging for researchers to track these zero-click attacks because targets may not notice anything suspicious on their phone. Even if they do observe something like “weird” call behavior, the event may be transient and not leave any traces on the device.

The shift towards zero-click attacks by an industry and customers already steeped in secrecy increases the likelihood of abuse going undetected. Nevertheless, we continue to develop new technical means to track surveillance abuses, such as new techniques of network and device analysis.

iMessage Emerges as a Zero-Click Vector

Since at least 2016, spyware vendors appear to have successfully deployed zero-click exploits against iPhone targets at a global scale. Several of these attempts have been reported to be through Apple’s iMessage app, which is installed by default on every iPhone, Mac, and iPad. Threat actors may have been aided in their iMessage attacks by the fact that certain components of iMessage have historically not been sandboxed in the same way as other apps on the iPhone.

For example, Reuters reported that United Arab Emirates (UAE) cybersecurity company DarkMatter, operating on behalf of the UAE Government, purchased a zero-click iMessage exploit in 2016 that they referred to as “Karma,” which worked during several periods in 2016 and 2017. The UAE reportedly used Karma to break into the phones of hundreds of targets, including the chairmen of Al Jazeera and Al Araby TV.

A 2018 Vice Motherboard report about a Pegasus product presentation mentioned that NSO Group demonstrated a zero-click method for breaking into an iPhone. While the specific vulnerable app in that case was not reported, a 2019 Haaretz report interviewed “Yaniv,” a pseudonym used by a vulnerability researcher working in Israel’s offensive cyber industry, who seemed to indicate that spyware was sometimes deployed to iPhones via Apple’s Push Notification Service (APNs), the protocol upon which iMessage is based:

“An espionage program can impersonate an application you’ve downloaded to your phone that sends push notifications via Apple’s servers. If the impersonating program sends a push notification and Apple doesn’t know that a weakness was exploited and that it’s not the app, it transmits the espionage program to the device.”

The Gulf Cooperation Council: A Booming Spyware Market

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries is one of the most significant customer bases for the commercial surveillance industry, with governments reportedly paying hefty premiums to companies that provide them special services, including analysis of intelligence that they capture with the spyware. The UAE apparently became an NSO Group customer in 2013, in what was described as the “next big deal” for NSO Group after its first customer, Mexico. In 2017, Saudi Arabia (which the Citizen Lab calls KINGDOM) and Bahrain (PEARL) appear to have also become customers of NSO Group. Haaretz has also reported that Oman is an NSO Group customer, and that the Israeli Government prohibits NSO Group from doing business with Qatar.

Al Jazeera and the Middle East Crisis

The relationship between Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain, Egypt (jointly, “the four countries”) and Qatar is fractious. The four countries often claim that Qatar shelters dissidents from the four countries and supports political Islamist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, whom they view as the most serious challenge to the existing political order in the Middle East.

In March 2014, Saudi Arabia, UAE and Bahrain withdrew their ambassadors and froze relations with Qatar for eight months. A second crisis occurred on June 5, 2017, when the four countries cut off diplomatic relations and closed their borders with Qatar. The crisis was ostensibly precipitated by a fake story planted on the state-run Qatar News Agency (QNA) by hackers, which misquoted Qatar’s Emir referring to Iran as “an Islamic power,” and praising Hamas. According to US intelligence officials speaking with The Washington Post, senior UAE Government officials approved the QNA hacking operation.

On June 23, 2017, the four countries issued a joint statement which outlined 13 demands to Qatar, including closing a Turkish military base in Qatar, scaling down ties with Iran, and shutting down Al Jazeera and its affiliate stations and news outlets.

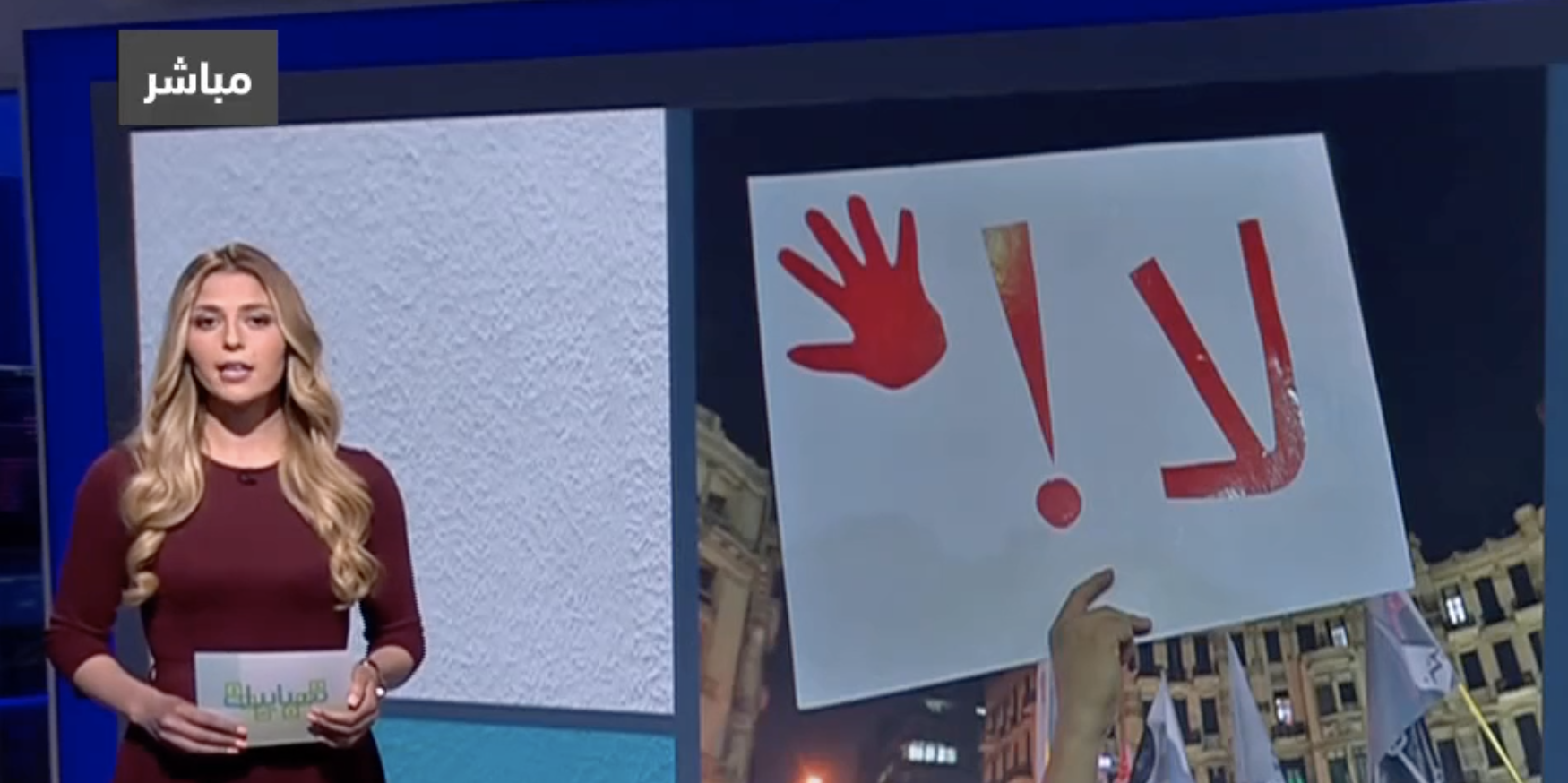

Al Jazeera: Targeted by Criticism, Hacking & Blocking by Neighbouring Countries

Al Jazeera is somewhat distinctive in the Middle East in terms of its media coverage. On many issues, it presents alternative viewpoints not available from largely state-run media outlets in the region. Several other attempts at building credible media channels in the GCC have been met with less success, including Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal’s highly publicized Bahrain-based Al Arab channel, which was permanently shut down by local authorities on its first day of operations after airing an interview with a member of Bahrain’s opposition Al Wefaq political society.

Al Jazeera’s reporting featured prominently in the Arab Spring, where its extensive, real-time coverage of protests in Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and Libya “helped propel insurgent emotions from one capital to the next.” Leaders of countries neighboring Qatar regularly express deep concerns about its coverage and in some cases have taken action to limit the availability of the channel in their countries. In 2017, both Saudi Arabia and the UAE blocked Al Jazeera’s website.

After the fall of Egypt’s President Mubarak in the Arab Spring, Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Morsi was elected President of Egypt. This election was considered by Saudi Arabia and the UAE as a threat and a sign of the expansion of Qatar’s regional influence because of Qatar’s history of support for the Muslim Brotherhood. However, Morsi was deposed by a military coup on July 3, 2013 led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and taken to military custody. One day after the coup, the military shut down a number of news stations in Egypt, including Al Jazeera Mubasher Misr and Al Jazeera’s bureau in Egypt, and detained five of the staff.

Although Al Jazeera’s Arabic language coverage of uprisings in neighboring Gulf countries, including Bahrain, was generally seen as striking a more muted tone than its English language coverage, the channel was still criticized. For example, Bahrain’s Foreign Minister famously tweeted the following about a documentary on the channel: “It’s clear that in Qatar there are those who don’t want anything good for Bahrain. And this film on Al Jazeera English is the best example of this inexplicable hostility.”

2. The Attacks

This section describes the hacking of two reporters’ phones, Tamer Almisshal and Rania Dridi. They are among the 36 reporters and editors targeted in the attack, most of whom have requested anonymity. Almisshal and Dridi consented to be named in this report and for the Citizen Lab to describe their targeting in detail.

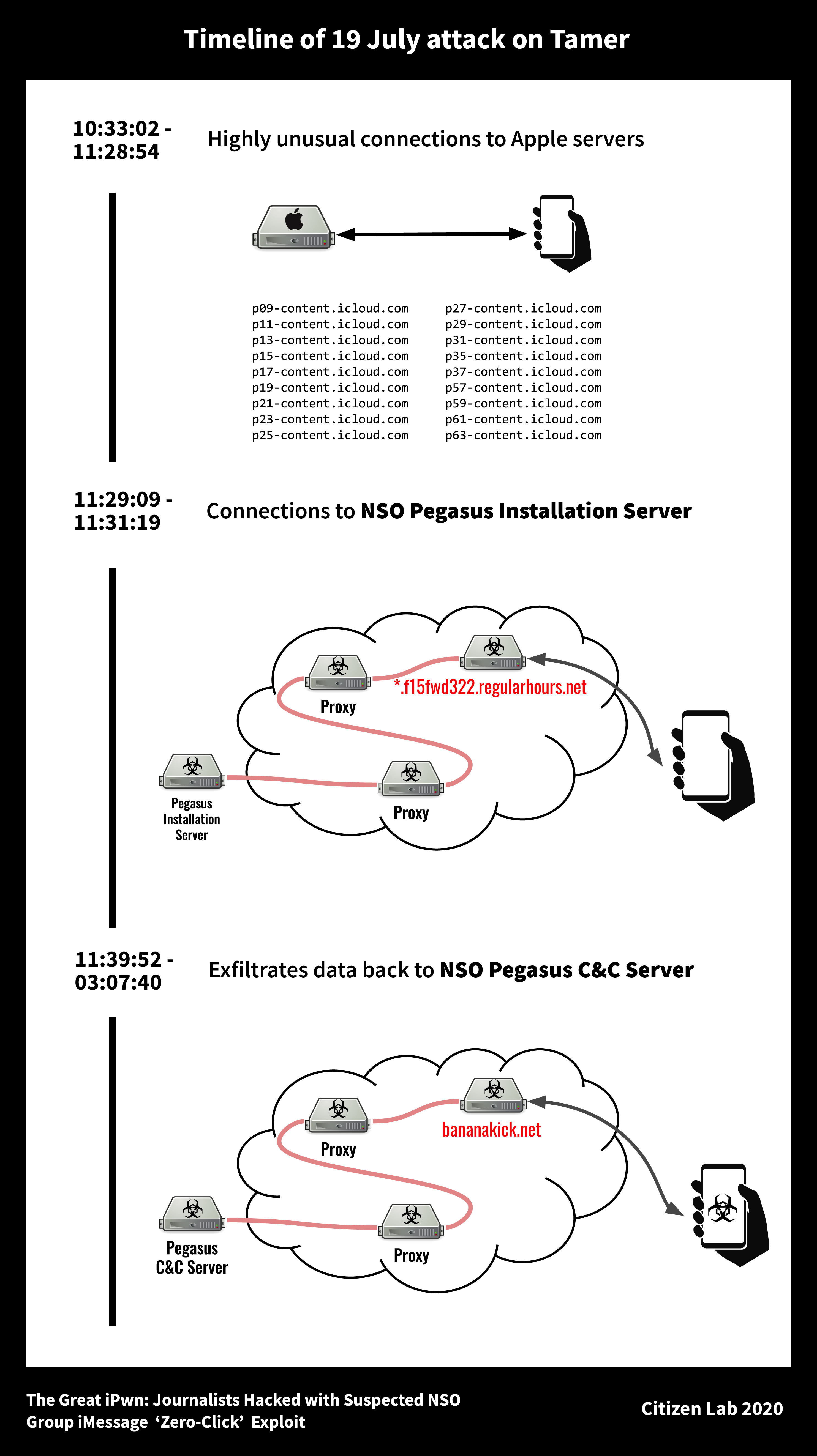

The 19 July 2020 Attack on Tamer Almisshal

Tamer Almisshal is a well-known investigative journalist for Al Jazeera’s Arabic language channel, where he anchors the “ما خفي أعظم” program (translated as “this is only the tip of the iceberg” or “what is hidden is more immense”). Almisshal’s program has reported on a wide variety of politically sensitive topics in the Middle East, including UAE, Saudi, and Bahraini Government involvement in an attempted 1996 coup in Qatar, the Bahrain Government’s hiring of a former Al-Qaeda operative for an assassination program, the Saudi killing of Jamal Khashoggi, and ties between a powerful member of the UAE’s Royal Family, Sheikh Mansour Bin Zayed Al-Nahyan, and UAE businessman B.R. Shetty’s healthcare empire, which collapsed in 2020 due to alleged fraud and disclosures of hidden debt.

Almisshal was concerned that his phone might be hacked, so in January 2020, he consented to installing a VPN application for Citizen Lab researchers to monitor metadata associated with his Internet traffic.

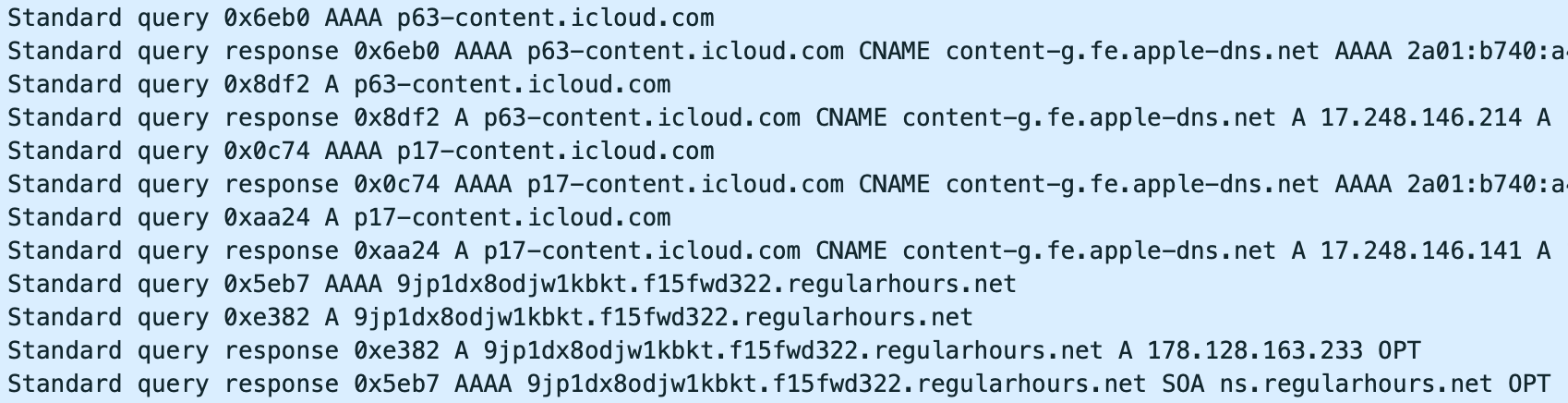

While reviewing his VPN logs, we noticed that on 19 July 2020, his phone visited a website that we had detected in our Internet scanning as an Installation Server for NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware, which is used in the process of infecting a target with Pegasus.

Time: 19 July 2020, 11:29 – 11:31 UTC

Domain: 9jp1dx8odjw1kbkt.f15fwd322.regularhours.net

IP: 178.128.163.233

Downloaded: 1.74MB

Uploaded: 211KB

Initial Vector: Apple Servers

We conclude that Almisshal’s phone reached out to the Pegasus Installation Server due to an apparent exploit delivered through Apple’s servers. In the 54 minutes before Almisshal’s phone visited the Pegasus Installation Server, we observed an unusual behavior: connections to a large number of iCloud Partitions (p*-content.icloud.com). In the more than 3000 hours that we have been monitoring Almisshal’s Internet traffic, we have only seen 258 connections to iCloud Partitions (excluding p20-content.icloud.com, which Almisshal’s phone uses for iCloud backups), with 228 of these connections (~88%) occurring during a 54 minute period between 10:32 and 11:28 on 19 July.1 On 19 July, we saw no matching connections prior to 10:32 or after 11:28. The connections in question were to 18 iCloud partitions (all odd-numbered).

The connections to the iCloud Partitions on 19 July 2020 resulted in a net download of 2.06MB and a net upload of 1.25MB of data. Because these anomalous iCloud connections occurred—and ceased—immediately prior to Pegasus installation at 11:29 UTC, we believe they represent the initial vector by which Tamer Almisshal’s phone was hacked. Our analysis of an infected device (Section 3) indicates that the built-in iOS imagent application was responsible for one of the spyware processes. The imagent application is a background process that appears to be associated with iMessage and FaceTime.

Exfiltration

Sixteen seconds after the last connection to the Pegasus Installation Server, we observed Almisshal’s iPhone communicate for the first time with three additional IPs over the next 16 hours. We never observed his phone communicating with these IPs previously, and have not observed communications since.

| Times (UTC) | IP | Uploaded | Downloaded |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7/19/2020 11:31 – 7/20/2020 03:09 | 45.76.47.218 | 133.06MB | 7.53MB |

| 7/19/2020 11:31 – 7/20/2020 03:08 | 212.147.209.236 | 75.94MB | 4.30MB |

| 7/19/2020 11:31 – 7/20/2020 03:09 | 134.122.87.198 | 61.16MB | 3.32MB |

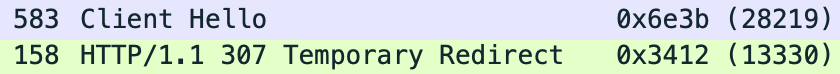

Overall, we observed 270.16MB of upload, and 15.15MB of download, and each IP returned a valid TLS certificate for bananakick.net. The phone did not set the SNI in the HTTPS Client Hello message, nor did it perform a DNS lookup for bananakick.net, perhaps an effort to thwart our previously-reported DNS Cache Probing technique to locate infected devices, or an effort to thwart anti-Pegasus countermeasures implemented nationwide in Turkey (Section 4), another popular target of Pegasus operators. Because communications with these three servers commenced 16 seconds after the communications with a known Pegasus Installation Server, we suspected that these three IPs were Pegasus command and control (C&C) servers.

Analysis of Device Logs

Almisshal’s device shows what appears to be an unusual number of kernel panics (phone crashes) between January and July 2020. While some of the panics may be benign, they may also indicate earlier attempts to exploit vulnerabilities against his device.

| Timestamp (UTC) | Process | Type of Kernel Panic |

|---|---|---|

| 2020-01-17 01:32:09 | fileproviderd | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-01-17 05:19:35 | mediaanalysisd | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-01-31 18:04:47 | launchd | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-02-28 23:18:12 | locationd | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-03-14 03:47:14 | com.apple.WebKit | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-03-29 13:23:43 | MobileMail | kfree |

| 2020-06-27 02:04:09 | exchangesyncd | Kernel data abort |

| 2020-07-04 02:32:48 | kernel_task | Kernel data abort |

A Series of Attacks on Rania Dridi

Rania Dridi is a journalist at London-based Al Araby TV, where she presents the “شبابيك” newsmagazine program (translated from Arabic as “windows”), which covers a variety of current affairs topics.

While reviewing device logs from Rania Dridi’s iPhone Xs Max, we found evidence that her phone was hacked at least six times with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware between 26 October 2019 and 23 July 2020. Two of these instances, on 26 October and 12 July, were likely zero-day exploits, as the phone appears to have been hacked while running the latest available version of iOS. At the other times Dridi’s phone was hacked, there was a newer version of iOS available, meaning that there is no evidence one way or the other as to whether the exploits were zero-days.

| Approx. Infection Time | iOS Version | Zero-Day? |

|---|---|---|

| 10/26/2019 13:26:26 | 13.1.3 | Yes |

| 10/29/2019 8:49:44 | 13.1.3 | |

| 11/25/2019 8:55:41 | 13.1.3 | |

| 12/9/2019 11:15:06 | 13.1.3 | |

| 7/12/2020 23:35:13 | 13.5.1 | Yes |

| 7/23/2020 7:14:08 | 13.5.1 |

On 26 October 2019, a Pegasus operator apparently successfully deployed a zero-day exploit against Dridi’s up-to-date iPhone running iOS 13.1.3 and, on 12 July 2020, a Pegasus operator apparently successfully deployed a zero-day exploit against the same up-to-date phone, running iOS 13.5.1. The 12 July 2020 attack, and another attack on 23 July 2020 appear to have used the KISMET zero-click exploit.

Network logs show that Dridi’s phone communicated with the following four servers between 13 July 2020 and 23 July 2020 that we attributed to NSO Group operator SNEAKY KESTREL. No communications were observed between 17 July and 22 July 2020.

| Times (UTC) | IP | Uploaded |

|---|---|---|

| 07/13/2020 09:13 – 07/23/2020 16:20 | 31.171.250.241 | 18.31MB |

| 07/13/2020 09:13 – 07/23/2020 16:19 | 165.22.80.68 | 15.92MB |

| 07/13/2020 09:13 – 07/23/2020 16:12 | 159.65.94.105 | 12.42MB |

| 07/13/2020 09:13 – 07/23/2020 16:09 | 95.179.220.244 | 8.43MB |

We suspect that the attacks on Dridi’s phone in October, November, and December 2019 also used a zero-click exploit, because we saw an NSO Group zero-click exploit deployed against another iPhone target during this timeframe, and because we found no evidence of telltale SMS or WhatsApp messages containing Pegasus spyware links on her phone. Network logs were unavailable for these periods.

4. Other Infections at Al Jazeera

Working with Al Jazeera’s IT team, we identified a total of 36 personal phones inside Al Jazeera that were hacked by four distinct clusters of servers which could be attributable to up to four NSO Group operators. An operator that we call MONARCHY spied on 18 phones, and an operator that we call SNEAKY KESTREL spied on 15 phones, including one of the same phones that MONARCHY spied on. Two other operators, CENTER-1 and CENTER-2, spied on 1 and 3 phones, respectively.

We conclude with medium confidence that SNEAKY KESTREL acts on behalf of the UAE Government, because this operator appears to target individuals primarily inside the UAE, and because one target hacked by SNEAKY KESTREL previously received Pegasus links via SMS that point to the same domain name used in the attacks on UAE activist Ahmed Mansoor.2

| IPs | CN in TLS Certificate |

|---|---|

| 134.209.23.19 | *.img565vv6.holdmydoor.com |

| 31.171.250.241 165.22.80.68 95.179.220.244 159.65.94.105 | *.crashparadox.net |

Servers used by SNEAKY KESTREL in Al Jazeera spying.

We conclude with medium confidence that MONARCHY acts on behalf of the Saudi Government because the operator appears to target individuals primarily inside Saudi Arabia, and because we observed this operator hack a Saudi Arabian activist who was previously targeted by KINGDOM.3

| IPs | CN in TLS Certificate |

|---|---|

| 178.128.163.233 | *.f15fwd322.regularhours.net |

| 45.76.47.218 134.122.87.198 212.147.209.236 | bananakick.net |

Servers used by MONARCHY in Al Jazeera spying.

We considered but view as less likely the hypothesis that MONARCHY and SNEAKY KESTREL are both linked to the UAE. The UAE Government has been known to target Saudi activists, and both MONARCHY and SNEAKY KESTREL have been observed operating in concert in two cases: the case of Al Jazeera, and a case in Turkey, where the Turkish Computer Emergency Response Team apparently caught both operators at around the same time (Section 4). However, we are aware of only one phone that was targeted by both operators, and we are not aware of any infrastructructure overlap between the two operators. Additionally, each operator seems to primarily target in a different country, MONARCHY in Saudi Arabia and SNEAKY KESTREL in the UAE. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are reported to be Pegasus customers.

We are not able to determine the identity of CENTER-1 and CENTER-2, though both appear to target mainly in the Middle East.

| IPs | CN in TLS Certificate |

|---|---|

| 80.211.37.240 161.35.38.8 | stilloak.net |

Servers used by CENTER-1 in Al Jazeera spying.

| IPs | CN in TLS Certificate |

|---|---|

| 209.250.230.12 80.211.35.111 89.40.115.27 134.122.68.221 | flowersarrows.com |

Servers used by CENTER-2 in Al Jazeera spying.

We did not observe infection attempts for CENTER-1 and CENTER-2, so we are unsure which Pegasus Installation Servers were used.

The infrastructure used in these attacks included servers located in Germany, France, UK, and Italy using cloud hosting providers Aruba, Choopa, CloudSigma, and DigitalOcean.

3. Analysis of Device Logs from a Live Pegasus Infection

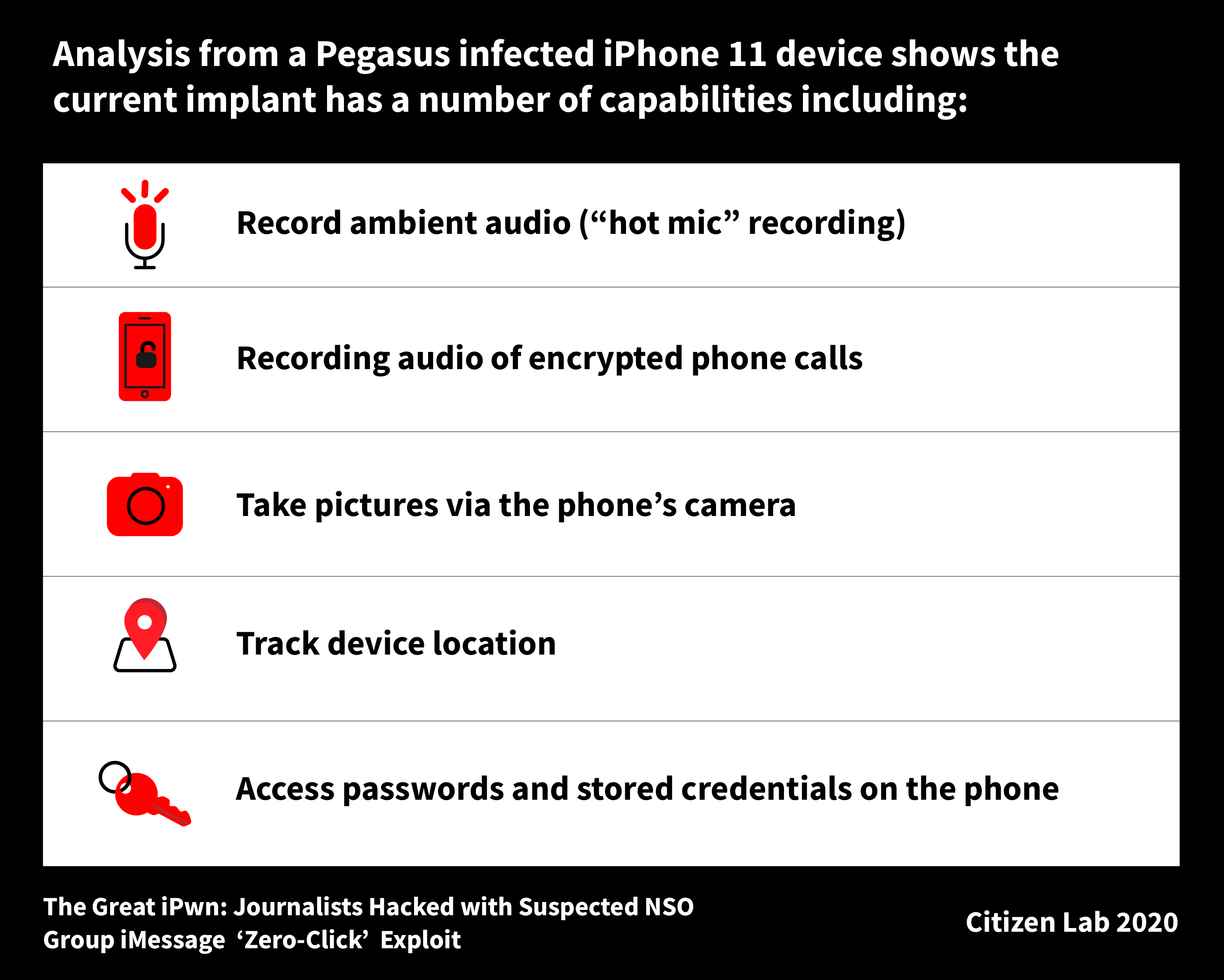

We obtained logs from an iPhone 11 device inside Al Jazeera networks while it was infected. Our analysis indicates that the current Pegasus implant has a number of capabilities including: recording audio from the microphone including both ambient “hot mic” recording and audio of encrypted phone calls, and taking pictures. In addition, we believe the implant can track device location, and access passwords and stored credentials.

The phone logs showed a process launchafd on the phone that was communicating with the four *.crashparadox.net IP addresses in Table 1, which we linked to SNEAKY KESTREL.

The launchafd process was located in flash memory in the com.apple.xpc.roleaccountd.staging folder:

/private/var/db/com.apple.xpc.roleaccountd.staging/launchafdThis folder appears to be used for iOS updates, and we suspect that it may not survive iOS updates. It appeared that additional components of the spyware on this device were stored in a folder with a randomly generated name in /private/var/tmp/. The contents of the /private/var/tmp/ folder do not persist when the device is rebooted. The parent process of launchafd was listed as rs, and was located in flash memory at:

/private/var/db/com.apple.xpc.roleaccountd.staging/rsThe imagent process (part of a built-in Apple app handling iMessage and FaceTime) was listed as the responsible process for rs, indicating possible exploitation involving iMessage or FaceTime. The same rs process was also listed as parent of passd, a built-in Apple app that interfaces with the keychain, as well as natgd, another component of the spyware, which was located in flash memory at:

/private/var/db/com.apple.xpc.roleaccountd.staging/natgdAll three processes were running as root. We were unable to retrieve these binaries from flash memory, as we did not have access to a jailbreak for iPhone 11 running iOS 13.5.1.

The phone’s logs show evidence that the spyware was accessing a variety of frameworks on the phone, including the Celestial.framework and MediaExperience.framework which could be used to record audio data and camera, as well as the LocationSupport.framework and CoreLocation.framework to track the user’s location.

Sharing Findings

We have shared our findings and technical indicators with Apple Inc. which confirms that it is investigating the issue.

4. Turkish CERT vs. NSO Group

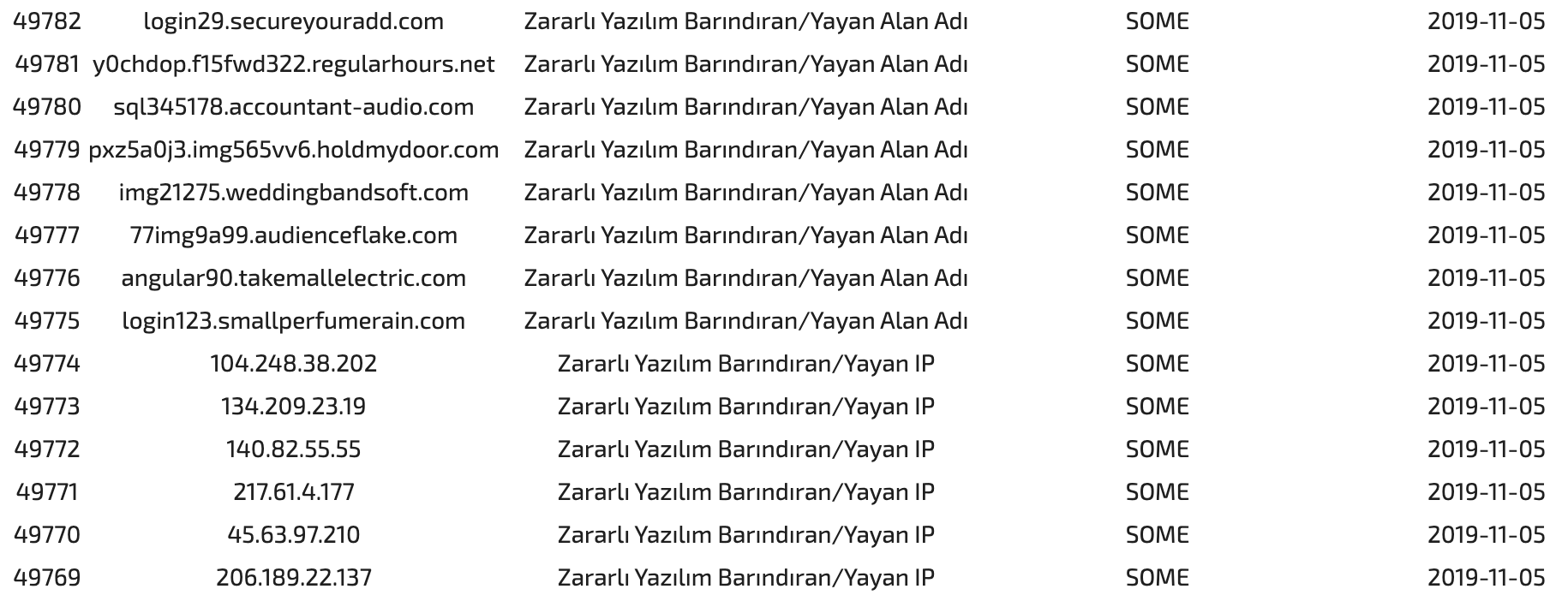

In late 2019, Turkey’s Government-run Computer Emergency Response Team (USOM) appears to have observed Pegasus attacks involving both MONARCHY and SNEAKY KESTREL, and sinkholed some domain names used by these operators on a national level.

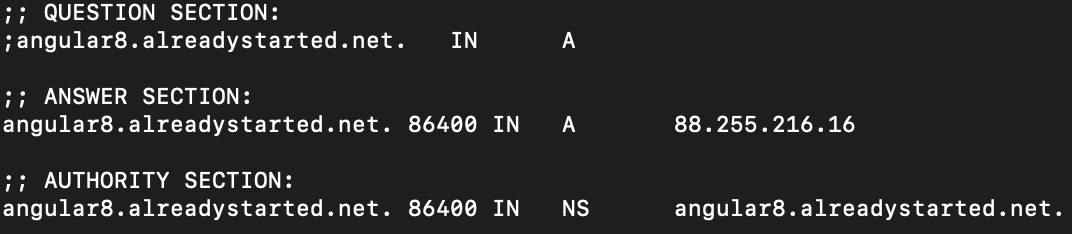

USOM publishes a “list of malicious links” (“zararlı bağlantılar”) available on their website. The list of indicators includes domain names, URLs, as well as IP addresses. Turkish ISPs generally redirect their subscribers who try to access indicators on this list to a USOM sinkhole IP address (88.255.216.16).

Each ISP appears to implement this sinkholing using the same technique they use to implement website censorship. For example, Turk Telekom appears to use their Sandvine PacketLogic devices to inject HTTP redirects for elements on the USOM list, whereas Vodafone Turkey appears to use its DNS tampering system, returning the USOM IP in response to any request for a domain name on the list.

It is clear that USOM has a particular interest in Pegasus, as all Pegasus domain names published in three Amnesty reports about Pegasus were added to the USOM list after Amnesty’s publication.4

Turkish CERT Sinkholes Pegasus Domains

On 5 November 2019, USOM added the following NSO Group Pegasus domain names and IP addresses to their list of malicious links. We attribute these domains and IPs to MONARCHY and SNEAKY KESTREL. These indicators were not previously published in any other location that we can identify, and the USOM list indicates that the source of the domains and IPs was one of Turkey’s SOMEs (institutional computer emergency response teams (CERTs) for government agencies and industries).

We suspect that USOM’s information about the Pegasus infrastructure came from observing specific infections, as opposed to a broader compromise of NSO Group, or a broader effort to fingerprint NSO Group traffic within Turkey. Several other operators that appeared to be spying inside Turkey with Pegasus at the time did not have their infrastructure sinkholed.

We are not aware which individuals were targeted in the attacks observed by the Turkish Government that triggered the sinkholing. However, a 2019 Reuters report mentions that, in 2016 and 2017, the UAE used the “Karma” exploit to hack hundreds of individuals around the world, including the Turkish Deputy Prime Minister.5

One of the IP addresses added to the USOM list on 5 November 2019 appears to have been abandoned by NSO Group on 28 October 2019, suggesting that at least some of the attacks observed by Turkey occurred prior to 28 October. Interestingly, despite the fact that regularhours.net and holdmydoor.com appeared on a Turkish CERT list in November 2019, we observed MONARCHY and SNEAKY KESTREL continue to use these domain names in attacks through August 2020.

5. Discussion: The Spyware Industry is Going Dark

When authoritarian governments are enabled by commercial spyware companies like NSO Group, and emboldened by the belief that they are acting in secret, they target critical voices like journalists. Unfortunately, it is increasingly difficult to track such cases.

The spyware industry does business in secret, and major spyware sellers invest heavily in fighting regulation and avoiding legal accountability. Yet, certain industry realities and technical limitations have historically made it possible to track infections. For example, for many years all but the most sophisticated commercially available spyware required some user interaction, such as opening a document or clicking a link, to infect a device.

The deception involved in tricking a target into becoming a victim left traces even after successful infections. These traces—especially messages used to seed spyware—have been an invaluable source of evidence for investigators. Over the years, by gathering and examining the ruses used to deliver spyware, often aided by victims themselves, it has been possible to identify hundreds of victims.

The current trend towards zero-click infection vectors and more sophisticated anti-forensic capabilities is part of a broader industry-wide shift towards more sophisticated, less detectable means of surveillance. Although this is a predictable technological evolution, it increases the technological challenges facing both network administrators and investigators.

While it is still possible to identify zero-click attacks—as we have done here—the technical effort required to identify cases markedly increases, as does the logistical complexity of investigations. As techniques grow more sophisticated, spyware developers are better able to obfuscate their activities, operate unimpeded in the global surveillance marketplace, and thus facilitate the continued abuse of human rights while evading public accountability.

Journalists Increasingly Targeted With Spyware

Counting the 36 cases revealed in this report, there are now at least fifty publicly known cases of journalists and others in media targeted with NSO spyware, with attacks observed as recently as August 2020. We have previously identified over a dozen journalists and civic media targeted with NSO Group’s spyware. Amnesty International has identified still more targeting, as recently as January 2020.

The Al Jazeera attacks are part of an accelerating trend of espionage against journalists and news organizations. The Citizen Lab has documented digital attacks against journalists by threat actors from China, Russia, Ethiopia, Mexico, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, among others. Other research groups have documented similar trends, which appear to be worsening with the COVID-19 pandemic. Often these attacks parallel more more traditional forms of media control, and in some cases physical violence.

The increased targeting of the media is especially concerning given the fragmented and often ad-hoc security practices and cultures among journalists and media outlets, and the gap between the scale of threats and the security resources made available to reporters and newsrooms. These concerns are likely particularly acute for independent journalists in authoritarian states who, despite the fact that they play a crucial role in reporting information to the public, may be forced to work in dangerous conditions with even fewer security tools at their disposal than their peers in large news organizations.

Progress, But New Perils

Journalist security has attracted recent research interest, grantmaking, and practice innovation. Progress is showing in many areas. However, the zero-click techniques used against Al Jazeera staff were sophisticated, difficult to detect, and largely focused on the personal devices of reporters. Security awareness and policies are essential, but without substantial investment in security, network analysis, regular security audits and collaboration with researchers like the Citizen Lab these cases would not have been detected.

Journalists and media outlets should not be forced to confront this situation on their own. Investments in journalist security and education must be accompanied by efforts to regulate the sale, transfer, and use of surveillance technology. As the anti-detection features of spyware become more sophisticated, the need for effective regulatory and oversight frameworks becomes increasingly urgent. The abuse of NSO Group’s zero-click iMessage attack to target journalists reinforces the need for a global moratorium on the sale and transfer of surveillance technology, as called for by the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, “until rigorous human rights safeguards are put in place to regulate such practices and guarantee that governments and non-State actors use the tools in legitimate ways.”

These safeguards should include strengthening and expanding regional and international export controls, enacting national legislation that constrains invasive new surveillance technology such as zero-click spyware, and the expansion of mandatory due diligence requirements for spyware developers and brokers.

Update your iOS Device Immediately

We have seen no evidence that the KISMET exploit still functions on iOS 14 and above, although we are basing our observations on a finite sample of observed devices. Apple made many new security improvements with iOS 14 and we suspect that these changes blocked the exploit. Although we believe that NSO Group is constantly working to develop new vectors of infection, if you own an Apple iOS device you should immediately update to iOS 14.

Acknowledgements

Bill Marczak’s work on this report was supported, in part, by the International Computer Science Institute and the Center for Long-Term Cyber Security at the University of California, Berkeley.

The authors would like to thank Bahr Abdul Razzak for review and assistance. Special thanks to several other reviewers who wish to remain anonymous as well as TNG. Thanks to Mari Zhou for design and layout assistance.

Financial support for this research has been provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Hewlett Foundation, Open Societies Foundation, the Oak Foundation, and Sigrid Rausing Trust.

Thanks to Al Jazeera and Tamer Almisshal for their investigative work on this project. Thanks to Al Araby and Rania Dridi.

Thanks to Team Cymru for providing access to their Pure Signal data.

- This analysis excludes connections to p20-content.icloud.com, which Almisshal’s phone uses for iCloud backups. ↩︎

- The target wishes to remain anonymous. ↩︎

- The target wishes to remain anonymous. The MONARCHY and KINGDOM operators may be the same operator, though we give them different names because we do not see any overlap in indicators of compromise. ↩︎

- No domains drawn from the Citizen Lab’s reporting on NSO Group appear on the list. ↩︎

- The positions of Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister were abolished in 2018. ↩︎