A confidential source sent the online news organization, The Intercept, a series of internal documents and communications providing details on what appear to be plans to develop and launch an Iranian mobile network, including subscriber management operations and services, and integration with a legal intercept solution. Some of this communication included representatives of the Communications Regulatory Authority of Iran (CRA). In October 2022, The Intercept shared this material with Citizen Lab researchers for analysis. The following report provides a summary of our analysis of this material and discusses its wider implications.

Key Findings

- Iran CRA regulations state that all telecom operators in Iran must provide the CRA with direct access to their system for retrieving user information and changing their services. Justified under its own broadly defined “Legal Intercept” provisions, the CRA aims to use this sophisticated system to store user information, allow or deny a user’s access to mobile services, and view historical voice, SMS, and data usage.

- The CRA’s Legal Intercept system uses APIs to integrate directly into mobile service providers’ operational systems, including acquiring detailed data on service ordering, service fulfillment, and billing history stored in the service provider data warehouse. Any new, termination, or change request for a user’s SIM card must be validated by the CRA, using the API from the mobile provider to request approval from the CRA prior to enacting the change.

- This type of state-sponsored system used to directly manage the operations of independent mobile networks in a country is extremely rare in the modern mobile communications industry. If implemented fully as envisioned in the documents we reviewed, it would enable state authorities to directly monitor, intercept, redirect, degrade or deny all Iranians’ mobile communications, including those who are presently challenging the regime.

- Documents indicate that firms based in Russia, the United Kingdom (UK), and Canada engaged in extensive discussions to provide commercial services and technology to support Iran’s Legal Intercept requirements of mobile surveillance, service control, and account management. While the documents we reviewed did not include fully executed agreements, the negotiations among the key stakeholders were advanced and revealed extensive details about Iran’s legal intercept system and the type of services and technologies that would be provisioned from the private sector to support it.

- A list of all documents we reviewed, and their timeframe, is included in Appendix A.

Background on Iran, Information Controls, and Democratic Protests

Iran’s recent history has been marked by repeated periods of political contestation. These include the student protests of 1999, the 2009 Green Movement, and protests over the country’s socio-economic situation in 2017/2018 and 2021. The September 2022 protests, which erupted after Mahsa Jina Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, was beaten to death in the custody of the morality police for allegedly violating strict hijab rules, are the latest manifestation in a long struggle for political rights and social justice.

The Iranian regime has responded to such protests with severe crackdowns and countless human rights abuses, including through arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances, gender-based and sexual-based violence, executions, and denying detainees a fair trial. Women, the LGBTQ+ community, and religious and ethnic minorities suffer systemic discrimination. In November 2022, the estimated death toll during the fall 2022 protests reportedly stood at over 300 people, along with over 14,000 people being arrested and some sentenced to death (in December 2022, another Iranian human rights organization based in the United States reported over 500 dead and over 18,000 arrested). Security forces have used indiscriminate shooting and live bullets against peaceful demonstrators. In short, Iran’s civil society, journalists, activists, and dissidents operate in a precarious and dangerous environment.

One prominent characteristic of the Iranian regime is the persistent violation of the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, freedom of thought, conscience, and religion, and access to information. The Islamic Republic has sought to impose restrictive measures to control information and activities in the digital space in various ways, including online surveillance, censorship, cyber espionage, the adoption of information control legislation, and policing online discourse. Iran ranks 178 out of 180 countries on the 2022 World Press Freedom Index and is considered “not free” in Freedom House’s 2022 Freedom on the Net report, which describes Internet freedom in the country as “highly restricted.”

For example, Iran has institutionalized Internet censorship through various government bodies. The Supreme Council of Cyberspace, established in 2012 by order of the Supreme Leader, centralized decision-making over internet development and control under the direct authority of Ayatollah Khamenei. Other important institutions include the Working Group to Determine Criminal Content, responsible for identifying web content to be filtered, and the Iranian Cyber Police (FATA), established in 2011 to combat cybercrime and threats against national security. Alongside these bodies, the CRA, founded in 2003, regulates the communications sector, including broadcasting and telecommunications.

The regime employs a range of sophisticated information control measures aimed at influencing and restricting information access, shaping online content, and stifling dissent. At the center is the government-controlled intranet, the National Information Network (NIN), which is also known as SHOMA or “halal internet.” Launched in 2012, the NIN project establishes and incentivizes the use of domestic internet infrastructures, purportedly with the aim of improving bandwidth, deepening internet penetration, protecting information security, and impeding international surveillance. In reality, users are subject to systematic monitoring, content blocking, and filtering. Freedom on the Net has reported that Iranian authorities are able to effectively block access to websites within a few hours. The result is Internet fragmentation, as siloed local infrastructures permit government authorities to block access to the global Internet while maintaining local connectivity.

Recent legislation, in particular the so-called User Protection Bill, threatens to complete Iran’s digital isolation. The highly controversial bill aims to give the security forces control over Iran’s Internet gateways, oblige foreign Internet services to follow the laws of the Islamic Republic, and criminalize the use of VPNs which enable Iranians to bypass censorship. The current administration seems to silently enact these measures although the bill has never been ratified by parliament. As part of the implementation, the government uses methods of deep packet inspection to detect and disrupt VPN connections in data traffic.

The Iranian authorities strategically use Internet shutdowns and disruption during elections and protests. For example, a nation-wide shutdown was implemented in response to the November 2019 protests. During the 5-day blackout, security forces killed an estimated number of up to 1,500 people. During and after the September 2022 protests, OONI reported a significant increase in Internet censorship, including the blocking of commonly used applications such as Instagram, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, Skype, the Google and Apple app stores, and encrypted DNS. The authorities also implemented daily shutdowns to Irancell, Rightel, and MCCI, the country’s top 3 mobile network providers.

Mobile Services in Iran are Far From Normal

The documents shared by The Intercept were a series of emails sent by representatives of the companies listed below, as well as documents attached to these emails (for a complete list of documents reviewed, see Appendix A). Citizen Lab researchers scanned the emails to confirm the authenticity of the sender, recipients, content, body, and document attachments. Companies (and one agency) whose correspondences we reviewed include:

- Ariantel – An Iranian-based Mobile Virtual Network Operator (MVNO), the primary source of the emails.

- Telinsol – A UK-based satellite communications consultancy which appears, based on the documents we reviewed, to have conducted international business transactions with vendors on behalf of Ariantel.

- PROTEI – An international telecommunications systems vendor founded in Russia which was selected, as indicated in the documents reviewed, by Ariantel to provide core network components to the company in support of user authentication, data management and Deep Packet Inspection (DPI), SMS delivery, and mobile network signaling.

- PortaOne – A Canada-based mobile business and support system vendor, which was selected, as indicated in the documents reviewed, by Ariantel to provide mobile account creation, service provisioning, billing, and customized integration with Iran’s Legal Intercept system.

- Iran CRA – Iran’s Communication Regulatory Authority, which is tasked with executing governmental powers, supervision, and executive powers of Iran’s Ministry of Information and Communication Technology.

The technical detail included in the documents sheds new light into the level of sophistication Iranian authorities sought to use to conduct surveillance operations and control access to mobile information and communications. The software and services offered by the vendors allows the CRA to integrate with mobile service provider systems used for billing, service activation, and management functions including a web service API called “SIAM”. The email shown below, sent by the CRA’s “Directorate General of Communications Systems Security,” seems to indicate that Ariantel has deployed a fully operational mobile network in Iran, integrating with the CRA’s Legal Intercept system, which has experienced a service interruption. Translated to English, it reads.

Greetings and Regards

The attached file containing Siam system documents was sent.

It should be noted that due to the frequent and long interruption of your service, please take the necessary measures to solve the problem and ensure the durability of the service.

Thanks

Ali Safai

Directorate General of Communication Systems Security

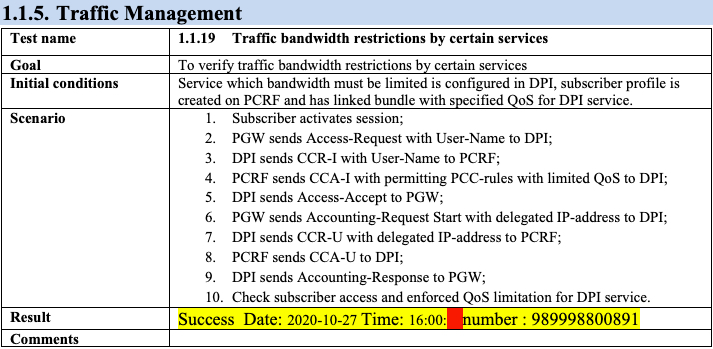

In addition to emails discussing integration requirements and meetings between the vendors regarding Ariantel’s MVNO project, the documents we reviewed provide a detailed overview of Iran’s system including technical specifications, network diagrams, proposals, and scope of work. An acceptance test document from PROTEI was provided to Ariantel confirming a successful test of “Traffic Management” including Internet service bandwidth restrictions, blocking of certain data services, and logging of Internet usage.

There are multiple mobile network operators within Iran, providing users with many options in their selection of service providers. These options include seven mobile network operators, as well as multiple MVNOs who provide their own branded services using those networks. It is general practice around the world for each mobile service provider to implement systems to provision new users onto their service, bill for the service, offer rate plans, and activate various features. These operations are performed within the service provider’s domain of control. However, we discovered that, in Iran, the envisioned domain of control would not belong to the service provider; the domain would be under the administrative control of the CRA legal intercept system (See Figure 2, below). To what extent this vision has been partially or fully implemented since the timeframe of the documents we reviewed is not clear (See Figure 2, below).

The CRA requires that each mobile service provider comply with requirements under a common framework set by the CRA, including directly interfacing with external systems operated by the regulatory authority to ensure legal compliance with information gathering about used services and disabling access to the service.

The Citizen Lab reviewed a document entitled “Legal Intercept”, which was authored by an Ariantel employee describing a new MVNO project with Telinsol. The document details the project with solutions to be supplied by PROTEI and PortaOne.

This document further describes the Iran Legal Intercept system as based on functional components working in tandem throughout Iran which, as described in documents and communications, include the following:

- LI (Legal Intercept) System – The component for conducting usage surveillance and control activity. The LI system gathers information about service usage from individual mobile users and may disable or modify access to the service. The CRA can request detailed usage records to be provided to the LI platform and disable the corresponding services. The LI system uses the SIAM web services API with each mobile service provider in Iran.

- CID (Control Illegal Devices) System – The component for alerting the CRA about changes to a user’s service profile of SIM cards provisioned on the network. CID informs the CRA about the current status of active SIM cards currently assigned or which are in the process of being assigned to a user.

- SHAHKAR System – A data warehouse which stores information about all mobile subscribers in Iran to check the “validity of users” and prohibit any registration attempt if the CRA determines the attempt to be invalid. The purpose of the SHAHKAR system is to notify the CRA of users attempting to change to a different service provider, update their subscription information or change their phone number. SHAHKAR prevents users from acquiring new mobile accounts with multiple service providers. Specifically, the documents refer to a use case where a new registration is attempted: “SHAHKAR verifies sent information and sees that this user is signed up with other providers. User creation is prohibited.” This description implies that Iran maintains a 1:1 mapping of a user to a SIM profile to simplify its ability to conduct surveillance operations. It provides the CRA with the ability to immediately cancel a user request for a new mobile account or make changes to existing accounts.

- SHAMSA – Shown as an interface for collecting bulk voice and SMS Call Detail Records (CDR’s) and data IP Detail Records (IPDR’s).

Iran’s Legal Intercept Architecture

The Legal Intercept system described in the documents would constitute a significant departure from standardized lawful intercept standards developed by 3GPP working groups and ETSI standards committees. These standards define processes and interfaces for the exchange of legal warrants, activation of communication interception, and delivering the communication content to the legal authority.

Iran’s Legal Intercept system differs from these standards with no facility for legal warrants, blanket delivery of user information during activation, and deep integration into mobile business systems for retrieving user content and changing access to services. Working in concert, the integration of LI, CID, SHAHKAR and SHAMSA components would provide the Iranian government with comprehensive information about Iranian subscribers, including personal information of citizens and non-citizens at the time they purchase SIM cards. The SHAHKAR system, referenced in the email below sent by a CRA staff member to Ariantel, uses a SIM registration API to supply this information during the activation process with mobile service providers, which is then screened by the system to determine whether the SIM activation is approved. Translated to English, the email reads:

Hi

The document of Shahkar inquiry is sent as an attachment

Thanks

Shirzad

Figure 4. Diagram prepared by the Citizen Lab which shows the relationship between Iran’s Legal Intercept System Interfaces and Mobile Service Provider Systems along with examples of Legal Intercept System Commands that query user information and control services

The diagram above, created by the Citizen Lab from technical specifications in the documents, shows elements selected by Ariantel which would play key roles in Iran’s legal intercept capabilities. These elements include the business support system providing usage CDR’s, SIM card updates, and the HLR/HSS (Home Location Register and Subscriber Server), which maintains a user’s network location and authorizes voice, SMS, and data services. The LI component uses multiple API commands to query user information and issue control commands to the mobile service provider in real time. It also defines a process to pull historical usage details, such as CDR’s, from the mobile service provider systems into SHAMSA for storage.

The documents show that products from Canadian-based vendor PortaOne and PROTEI, including the PortaBilling Converged Business Support System (BSS), were selected by Ariantel to provide information to Iran’s Legal Intercept system components. While we have no evidence that final agreements were executed for this system, the discussions around its implementation appear to have been well-advanced. The BSS is the primary mobile system used for storing information about customers, configuring and billing for services, and managing services such as provisioning new or changing existing user services. The PortaOne system integrates with systems provided by PROTEI, and, if implemented, would supply detailed usage information to the Legal Intercept system while receiving information about requests for new or updated services (all without user knowledge). In addition, commands from the CRA interact with the Ariantel network to suspend and control voice and data services and supply the location of users on the network.

The surveillance and censorship capabilities resulting from this level of integration with mobile service providers cannot be understated. Because Iranian authorities would receive information from all mobile service providers, they would have deep visibility into all services used, who is communicating with whom, for how long, how often, and where. They could also identify the current phone numbers used in certain geographic areas based on CellID or street address. This information could be used to decide who, what, and when to place restrictions or make changes to a user’s mobile service plan, such as the user’s social community or the location of political demonstrations. They could also view extensive personally identifiable details when users sign up for mobile services including:

- Name

- Family

- Father’s name

- Number of birth certificate

- Birth date

- Birthplace

- Home Telephone Number

- Email Address

- Gender

- Zip Code

- Nationality

- Passport Number

- Postal Address/Home Addresses

Findings: Iranian Mobile Surveillance and Control Real Time API

The documents show API commands used by Iranian authorities to query user information and change user services. Citizen Lab researchers have extracted the API commands from the SIAM document and grouped them into the tables (presented below) to show those that could be used for surveillance, for modifying services, and testing results for enforcing bandwidth restrictions of data applications.

SURVEILLANCE-RELATED API COMMANDS (SIAM Web Service)

The following commands allow the CRA to search for users and retrieve personal information and related usage.

The commands span virtually all usage associated with a mobile user, or a collection of users within a specific location. The CRA can use the SIAM API with a user parameter (Name, Family, Passport, IP Address, Phone Number, MAC Address, IMEI, etc.) to request information. The API documentation also indicates that Iran may have visibility into the type of network available to the user termed as “Connection base” (such as cellular versus WiFi).

| API REQUEST | DESCRIPTION | RESPONSE DETAILS |

|---|---|---|

| GetIPDR | Request information on a user’s Internet sessions tdat took place during a specific time period. | Includes the date/time, ports used to identify the applications used and websites visited, duration of the session, data volume, and location of the user during that Internet session. |

| GetCdr | Request information on the history of a user’s voice calls and SMS messages. | Includes the calling and called numbers, duration of call, type of call (including during international travel), messages, and location during use. |

| FullSearchByNum | Request details about a user’s mobile service and personal details. | Includes family information, passport details, home address, billing history, and types of mobile services available to the user. |

| BillingInfoSearch | Request details about a user’s mobile service financial transactions. | Includes billing invoice date and amount, payments made and amount, and type of charge (such as international calling). |

| ListOfPhoneServices | Request details about the different mobile services available to a user. | Includes the services included in the user’s rate plan, such as video calling, international roaming, ringback tones, call forwarding, etc. |

| DivertInfoSearch | Request details about a user’s call forwarding status. | Includes the phone number the user has configured for call forwarding. |

| LocationCustomerList | Request a list of phone numbers in a geo-location by providing the LaCellId (Location Area Code+Cell ID) and address. | Includes a list of phone numbers and IMEI’s of users who are currently attached to a cellular base station and address. |

| ApnOwnerSearch | Request the owner of a particular APN (Access Point Name). | Provides the identity details of the owner of a private data connection used by certain mobile phone numbers. This function could be used to identify a collection of users who may be using a special type of mobile service such as a data card, or private business connection. |

Table 1. Table compiled by the Citizen Lab showing a list of required SIAM API surveillance query methods used by Iran CRA

CONTROL-RELATED API COMMANDS (SIAM Web Service)

The following commands (Table 2) allows the CRA to apply immediate changes to a user’s service and remove the requested changes when no longer required.

Media stories suggest that Iran has employed controls to shut down mobile services or block Internet traffic. We can confirm through the documentation shared with the Citizen Lab that in addition to blocking services, the CRA could change call forwarding rules, force the phone to use a slower 2G network, and block access to services based on location. This API allows Iranian authorities to have the flexibility to place partial blocks on phone calls or data services, allowing authorities to apply network policies in a highly granular manner, such as blocking incoming or outgoing calls or modify certain call forwarding criteria.

| API REQUEST | DESCRIPTION | RESPONSE DETAILS |

|---|---|---|

| ApplySusp

ApplySuspIP |

Block incoming, outgoing, all voice calls or disconnect a call currently in progress. Block all current data sessions permanently. | Calls can be blocked or the block can be removed. Data sessions can be suspended for a period of time, such as 1 day, 3 days, etc. |

| ApplyDivert | Remove a user’s call forwarding settings or forward all incoming calls to another number. | Calls can be forwarded based on multiple criteria, such as all calls, missed calls, and when the line is busy or unavailable. |

| Force2GNumber | Disable all 3G and 4G data services, forcing a user’s phone to only use 2G data speeds. | The phone can be forced to 2G, then enable the phone to register to 3G and 4G service at any time. |

| SuspOrder | Block an order for a mobile service or prevent a user’s request to change a mobile service. | There are a number of criteria that can be used to block or unblock a service request. |

Table 2. Citizen Lab created list of required SIAM API blocking commands used by Iran CRA

The screenshot below taken from the SIAM document shows the command used for blocking data services:

IP TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT

While not listed explicitly in the SIAM API document, the Citizen Lab reviewed an acceptance test document from PROTEI, performed on behalf of Ariantel, verifying that data services can be restricted based on multiple criteria – as shown in the screenshot below from the document. The PROTEI DPI can classify user data into service types, such as WhatsApp, Facebook, or Twitter and restrict the bandwidth/Quality of Service (QoS) of that service type, making the service unusable. It allows for the following commands:

- Restrict bandwidth for certain websites or apps for a user

- Block data traffic for certain websites or apps for a user

- Block all data for a user

- Block all data for all users

These commands and test cases (shown in Figure 16) from PROTEI show the extensive data restriction capabilities available to the CRA via deep mobile network integration to mitigate user communications inside and outside of Iran.

Foreign Corporate Entities: Telinsol, PROTEI, and PortaOne

Our review of the documents provided by The Intercept suggests that companies based in the UK, Russia, and Canada explored providing commercial services that, based on our review of the documents, would support the CRA’s surveillance, control, and account management capabilities.

Prior to publishing this report, on January 4, 2023, we provided a summary of our research findings to Telinsol, PROTEI, and PortaOne and offered them a week to respond along with an undertaking to publish their response in full. We received a response from PortaOne on January 11, 2023 and the company made an official statement on January 11, 2023. We received a response from Telinsol on January 11, 2023, and another on January 13, 2023. All responses and the official statement have been included as Appendix C to the report.

Telinsol Ltd.

Telinsol Ltd. is a UK-based telecommunications company that was founded in 2015. It is a private limited company that, according to their website, engages in telecommunications and information technology consulting, support services, equipment supply, and satellite telecommunications. We viewed the company’s LinkedIn page on December 6, 2022, but it has since been removed.

Nima Eskandari, an Iranian national, is one of the company’s two listed directors (the other director is identified as Simon Edward Maddox). Mr. Eskandari describes himself as the company’s founder on LinkedIn and is identified as the company’s Managing Director in email correspondence. Mr. Maddox was listed as an employee of Telinsol on the company’s LinkedIn profile before it was taken down. He has kept a reference to the company in his LinkedIn byline.

We also noted that, on December 6, 2022 when we viewed his LinkedIn profile, an individual called Akbar Ghahri identified himself as “Head of Satellite Services” at Telinsol from January 2021-Present, while also identifying himself as “Managing Director” of SamanTel, which describes itself as the first MVNO license holder in Iran from October 2020-Present. Mr. Ghahri appears to have removed the reference to Telinsol on his LinkedIn profile. In what appears to be his Twitter profile, Mr. Ghahri identifies himself as working for a telecommunications company and being based in Iran, while his LinkedIn profile lists that he is based in the UK. On this webpage, an “Akbar Gh” is identified as a satellite engineer at Telinsol.

There are several other ties between Telinsol and Iran, including evidence suggesting that Telinsol, as a UK-based company, may be working on behalf of Ariantel.

In one document we reviewed, which was sent by an Ariantel software manager as an attachment to individuals at PortaOne, Ariantel, and Telinsol, the following language is included: “Telinsol is [sic] Mobile Virtual Network Operator in Iran”1 and that “[t]o provide services in Iran every MVNO must comply with legal requirements and have Legal Intercept.” The document goes on to describe the Legal Intercept system in Iran.

Documents attached in the emails shared with the Citizen Lab appear to show Telinsol facilitating purchases to support Ariantel’s MVNO launch, including SIM cards, the PortaOne solution, and coordinating meeting logistics for training Ariantel staff on the operation of the PROTEI DPI solution. Direct email communications between Mr. Eskandari, PortaOne, and Ariantel include commercial proposals, equipment purchase orders, training, logistics, and contract details. As evidenced by the screenshots of emails below from June and August 2019, an agreement appears to have been concluded among the parties that Ariantel representatives use Telinsol, Gmail or Yahoo email addresses to communicate. A comparison of the two emails confirms that Ariantel representatives are using both Telinsol and Ariantel email addresses, suggesting an affiliation between the companies.

Internal Ariantel emails shown below reference commercial material provided in .zip files, including commercial documents from PortaOne to Mr. Eskandari.

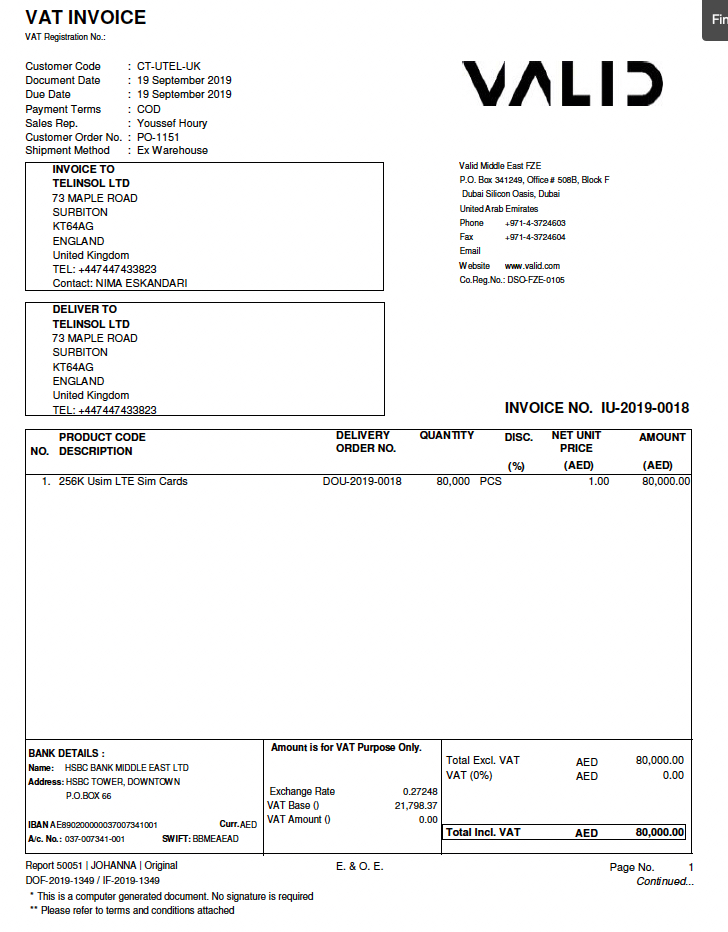

In addition to the PortaOne quotation, an invoice was sent from Valid, a Brazil-based SIM Card provider, to Ariantel email recipients referencing a Telinsol purchase order, further suggesting that Telinsol may have acted as a procurement partner with Ariantel.

Mr. Eskandari was also seen facilitating meetings between Iranian-based Ariantel and Russian-based PROTEI personnel as evidenced by the emails below.

Mr. Eskandari and fellow Telinsol Director, Mr. Maddox, are also directors of Emeatra Ltd., another UK-based company that supplies new and used telecommunications and network equipment. They are also directors in another UK-based company called Agtelligence Ltd., which is described on LinkedIn as “[h]elping UK farmers on their journey to sustainability.”

Response from Telinsol

On January 11, 2023, DLA Piper (Canada) LLP sent an email to the Citizen Lab on behalf of Telinsol. In this response, Telinsol stated that it:

…flatly denies the allegation that it has been involved in activities that would in any way help digital espionage against Iranian citizens. In particular, the suggestion in your letter that Telinsol provides commercial services to support Iran’s Legal Intercept requirements of mobile surveillance, service control and account management is entirely false and any publication of such an allegation would cause irreparable harm to Telinsol, as well as to the reputation of its past and present clients.

The company further urged the Citizen Lab to “eliminate any reference to Telinsol in its report” and that it would “not hesitate to avail itself of all available legal remedies in response to a defamatory publication by Citizen Lab.”

In a subsequent letter dated January 13, 2023, DLA Piper (Canada) LLP followed up with another letter on behalf of Telinsol. In this letter, Telinsol stated, via counsel, that the “hacked emails evidence a relationship between Ariantel and PortaOne which pre-dates the involvement of Telinsol.” The emails “further evidence Telinsol entertaining an initial enquiry by Ariantel and PortaOne and thereafter entering a due diligence process – a due diligence process that ended in September, 2019 with Telinsol rejecting involvement in the project.” Telinsol also claims that “any activities that thereafter continued were with a Portugal-based company called Magicalcharacter.”

As noted in this report, the documents we reviewed did not include a signed agreement between Telinsol and Ariantel. However, the correspondence reviewed above, which took place in 2019, did include a number of indications that Telinsol may have been acting as a procurement partner with Ariantel at one point in time, as well as email exchanges involving Telinsol, PortaOne, PROTEI, and Ariantel.

Further, we also reviewed one email chain from 2021 between Telinsol, PROTEI, and Ariantel. In this correspondence the NFV EPC & PS Core Manager at Ariantel writes to Mr. Eskandari (Telinsol’s Director): “[k]indly based on our phone conversation and CEO order, please arrange PROTEI training team to come to Iran.” In this same email chain, Mr. Eskandari (Telinsol’s Director) asks “Vladimir,” an individual who appears to be working at PROTEI Russia, what the current travel policy is in Russia and whether it would be “possible to fly to Iran.”

This email chain was dated 2021, suggesting that Telinsol had some kind of involvement with Ariantel that arose after September 2019. It is not clear based on the documents we reviewed whether this correspondence from 2021 relates to the earlier discussions between PortaOne, Telinsol, and Ariantel that arose in 2019.

PROTEI Ltd.

PROTEI Ltd. is a Russian telecommunications, software and hardware company founded in 2002 and operating in Eastern Europe, Asia, Latin America, North Africa and the Middle East. While PROTEI advertises its headquarters in Estonia and its Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) branch in Jordan, its Russian origins are not widely advertised. The original PROTEI, called “PROTEI NTC” (Scientific-Technological Center PROTEI), is located in Saint-Petersburg. PROTEI has a dedicated Russian branch, PROTEI ST or “Special Technical Centre,” created to work with government agencies and military departments in the Russian Federation, including the Ministry of Defence and the National Defence Management Centre.

PROTEI is involved in developing a wide range of solutions for special communications (videoconferencing, Internet and mobile connectivity for the Russian army), but also DPI solutions. These technologies were exported to Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan,2 Tajikistan, Niger, and Bahrain. PROTEI representatives also visited Syria in August 2022 to discuss potential collaboration.

PROTEI has partnered with PortaOne, integrating numerous products between the two companies. In a joint press release in 2017 the companies announced the integration of PortaOne’s PortaBilling Business Support System (BSS) and PROTEI’s Home Location Register HLR/HSS and Policy Controller PCRF products, which enables MVNOs to manage subscribers and services independently of host network operators, and to launch new mobile networks. They had previously integrated PortaBilling BSS with PROTEI’s CAMEL Gateway and DPI Platform in 2016, which functions as a mechanism to enforce broadband usage policies. According to PortaOne documents, there is also interoperability with PROTEI PCRF, PROTEI PGW, PROTEI SMSC, and PROTEI USSD Gateway. In 2020, PROTEI and PortaOne announced completion of interoperability testing between PortaOne’s PortaBilling Business Support System (BSS) and PROTEI’s Home Location Register HLR/HSS and Policy Controller PCRF products.

As noted above, emails we reviewed included correspondence between Telinsol, PROTEI Russia, and Ariantel, where the parties are discussing the possibility of the “PROTEI training team” flying to Iran for a training on the instruction of Ariantel. As noted, Telinsol’s director, Mr. Eskandari, is asked by Ariantel to arrange this trip.

PortaOne Inc.

PortaOne Inc. is a Canadian telecommunications company based in British Columbia and founded in 2001. The company has two listed directors. Andriy Zhylenko, who has listed an address in Barcelona, Spain and is the company’s CEO, and Oleksandr Kapitanenko, the company’s President who has listed an address in Coquitlam, BC in Canada. PortaOne supplies software for telecommunications companies, including billing and charging platforms (PortaBilling) and service management and delivery systems for voice, messaging, IoT/M2M, and data traffic (PortaSwitch), among other software solutions.3

On the PortaOne customer webpage, they claim to have served over 500 clients in nearly 100 countries. While they do not name Iranian customers, the PortaOne website included, prior to January 11, 2023, a colour-coded installation map that indicated the company was involved in 2-3 installations in Iran. On January 11, 2023, after we received the response from PortaOne (see Appendix C) that installation map was updated to remove the Iran installations (see Figure 14). In a subsequent statement (also included in Appendix C), PortaOne explains that the map on their website mistakenly combined Iraq (where they have customers) with Iran (where they stated not to have customers) and that the map was subsequently corrected.

Responses from PortaOne

PortaOne provided the Citizen Lab with two responses prior to the publication of this report. On January 10, 2023, in the first response sent by their counsel, PortaOne stated that the company “does not provide any products or services to or for use in Iran, it has never done business with Iran, Telinsol or Ariantel” (see Appendix C).

On January 11, 2023, PortaOne issued an official statement contradicting the first response. In this statement, PortaOne stated that, in 2018 and 2019, a PortaOne sales manager engaged in business discussions with Ariantel, acting through Telinsol, regarding PortaOne’s products. The license deal submitted by the sales manager for approval by PortaOne’s management was not with Ariantel but with a Portuguese company. PortaOne explained that it did receive a single payment under the contract between PortaOne and a Portuguese company. The payment they received under this contract came from an unrelated entity, which prompted an investigation by senior management and led to the discovery that the Portuguese company was a front for Ariantel. PortaOne claims that it subsequently canceled the contract with the Portuguese company and returned the payment received.

It is hard to understand how PortaOne’s senior management was not aware of the connection between the Portuguese company (which Telinsol claimed in its January 13, 2023 response to us is named “Magicalcharacter”) and Ariantel and why such an investigation was not conducted by the company prior to entering into negotiations with the Portuguese company, let alone finalizing an agreement and receiving a payment. According to the email correspondence we reviewed, it was the Business Development Director at the time at PortaOne–which suggests a relatively senior position at the company–who was primarily involved in correspondence between PortaOne, Telinsol, and Ariantel. This Business Development Director was the one to request Telinsol to provide a Telinsol email to an individual who appeared to be using an Ariantel email address, and noted in that same email that, “[a]s agreed, all correspondence must be use [sic] ‘Telinsol’ or generic (Gmail or yahoo) email addresses” (See Figure 8).

It is also concerning that a PortaOne employee (and, in particular, a senior employee) would not have considered the adverse human rights impacts of this potential business relationship. This same Business Development Director, as well as the email address “[email protected],” was copied on an email where a software manager at Ariantel appears to have specifically asked someone in sales (a certain “Alex,” which is likely referring to Alexander Zalugovskiy, Project Manager, who is also identified in the documents reviewed) at PortaOne about “the list of APIs offering required data for LI” and noting that in their “last session talks as you said it seems that it’s possible for us to implement legal requirements.”

The email includes an attached document where it is specifically spelled out that “Telinsol is a Mobile Virtual Network Operator in Iran,” “Telinsol is going to use Protei and PortaOne solutions to run their MVNO services,” and that to provide services in Iran every MVNO “must comply with legal requirements and have Legal Intercept” which is composed of “three components. LI platforms…CID – Control Illegal devices…SHAHKAR – control validity of signed users.” This summary was then followed by an extensive description of each of these Legal Intercept components (See Figures 18 and 19).

Our review of the documents has not identified any exchanges with a Portuguese company or a company called Magicalcharacter acting on behalf of Ariantel. PortaOne’s public statement claims that a sales manager “on his own initiative, engaged in business discussions with Ariantel, acting through Telesol [sic]”. However, according to the email correspondence we have reviewed, PortaOne’s Business Development Director at the time was involved in direct correspondence with at least one individual using an Ariantel email address. As noted above, a document sent to two PortaOne email addresses included direct references to the proposed project involving an MVNO operating in Iran.

A set of documents that appear to have been prepared or edited by a project manager at PortaOne illustrate that at least two PortaOne employees were aware that the proposed project with Telinsol involved providing services to an Iran-based MVNO. In a document describing various features of the services PortaOne would provide to Telinsol, comments attributed to a ‘Alex Zalugovskiy’ at PortaOne make multiple references to components of the project requiring CRA approval. A set of documents from August 2019 that are described as having been prepared by ‘Alexander Zalugovskiy’, described as a ‘project manager’ at PortaOne, indicate that the proposed project with Telinsol required Farsi language support, as well as support for the Jalali calendar used in Iran. Together, the documents indicate that at least two employees of PortaOne were aware, or had reason to be aware, that the proposed project with Telinsol involved providing services to an Iran-based MVNO.

In sum, PortaOne’s communications to us have evolved from a blanket denial to an admission that some business was conducted and then subsequently investigated and closed down. However, the information contained in the documents we reviewed does not fully align with their explanation, nor does it demonstrate the type of due diligence they claim to follow.

Conclusion

The documents reviewed in this report provide a glimpse into the Iranian government’s attempt to build a comprehensive surveillance regime and the role of foreign entities in potentially facilitating that system. While we cannot say whether the surveillance system in question was fully or partially implemented, as we only have insight into a moment in time, these documents clearly do reflect an aspiration for an unprecedented surveillance architecture that would have–based on the Iranian regime’s history of suppressing dissent and human rights–led to further human rights violations. Further research is required to understand whether, and to what extent, this system was fully developed and if so, by whom.

In addition, the documents clearly show that several foreign firms were actively negotiating4 to provide services and technology that our analysis suggests would have helped facilitate the Iranian regime’s legal intercept capabilities. In addition to respecting domestic law (such as sanctions regimes), under the framework of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), corporate actors have a responsibility to respect human rights and seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts. While businesses may argue that their services are innocuous and not specifically designed for legal interception, this does not absolve them of the responsibility to undertake a human rights due diligence process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for how they will address adverse human rights impacts in the context of a potential client.

Further, in this case, the correspondence exchanged by the parties should have put the foreign companies on notice that their products could be integrated into a broad legal intercept architecture being operated by a government with a notoriously poor human rights record. As one example, in email discussions regarding the project exchanged between Ariantel and PortaOne in June 2019, Ariantel provided CRA Legal Intercept requirements, outlining the extent to which Iranian authorities required visibility into, and control of, user mobile services. Citizen Lab’s research into the email communications and documentation shared with vendors provide unmistakable clarity into the intentions of the Iranian regime with regard to regulations over mobile operator services.

UN Special Rapporteurs, governments, multi-stakeholder platforms, and telecommunications industry leaders have all recognized the significant impact of telecommunications products and services on freedom of expression and privacy, and have emphasized the need to implement such human rights assessment procedures. None of the companies who provided a response to this report have offered concrete information regarding having such a human rights due diligence process in place prior to engaging in business with new clients. In particular, PortaOne’s second response to the Citizen Lab raises serious questions regarding how the company vets clients for risks of adverse human rights impacts (as well as potential sanctions violations), what oversight is exercised by senior management, and what measures exist to ensure that similar situations do not arise in the future.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to Siena Anstis, Jakub Dalek and Bill Marczak for internal review, Mari Zhou for graphics, and Snigdha Basu for copy editing.

Appendix A. Documents Reviewed

The following table lists the documents included as attachments in email communications shared with the Citizen Lab for analysis by The Intercept.

| Date and Subject of Email | Email Recipient Domains | Document Attachment Titles |

|---|---|---|

| August 7, 2021

Siam Document |

|

|

| May 2, 2020

Shahkar-Estelam-Document |

|

|

| September 21, 2019

FW. Purchase Order PO-1151/ PO-0030 from Telinsol Ltd for VALID Middle East FZE |

|

|

| September 1, 2019

مستندات درخواستی English Translation “Requested documents” |

|

|

| August 18, 2019

Contract material with Porta One |

|

4.7.zip

|

| August 28, 2019

Final Agreement between Telinsol and Porta One |

|

|

| June 21, 2019

PortaOne Converged BSS-OSS and Billing for Telinsol in UK |

|

No Documents Attached |

| June 11, 2019

RE. APIs supporting Legal Intercept |

|

|

| April 28, 2019

Li& shahkar& CID |

|

|

| July 12, 2021

Re: Protei Training |

|

No Documents Attached |

Appendix B. Glossary

The following glossary includes a contextual list of specialized terms and acronyms used in this report.

- Access Point Name (APN) A name configured in the device and network which specifies the type of network data connection assigned to a user, such as an MVNO or other private mobile network.

- Business Support System (BSS) A software function responsible for storing information about mobile service provider products, rates, customers, customer information, or phone lines. It enables customer billing and controls service configuration and activation.

- Credit-Control-Answer (CCA) A command response from a PCRF used to provision rules and triggers to control a user data session, such as bandwidth limiting or data blocking.

- Credit-Control-Request (CCR) A command sent to a PCRF used to request rules to issue user data session controls, such as bandwidth limiting or data blocking.

- Call Detail Record (CDR) Provides detailed information about user voice calls or SMS messages including time, duration, location, source, and destination number.

- Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) An in-line software network function used by mobile service providers that receives and processes user data information, detects and classifies it into service types, and enables controls such as blocking, bandwidth restriction, and deep analysis.

- Home Location Register/Subscriber Server (HLR/HSS) A software network function that supports user mobile services including authentication, authorization, status, and communication with other network functions to enable voice, data, and messaging services.

- Internet Protocol Detail Record (IPDR) Provides detailed information about user data sessions including time, location, server IP address, data volume, service identification, protocol, subscriber identifier.

- Mobile Virtual Network Operator (MVNO) A mobile service provider that sells services under its brand name but uses the radio network of another licensed mobile operator.

- Policy and Charging Rules Function (PCRF) A software function used for receiving and activating rules for controlling a user data session.

- Packet Data Network Gateway (PGW) A software network function that routes and filters user data from the mobile network to external networks such as the Internet.

- Quality of Service (QoS) A description commonly associated with the amount of network bandwidth available to a user’s mobile data services.

- Short Message Center (SMSC) A software network function that stores and forwards SMS messages.

- Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) An interactive legacy mobile messaging protocol commonly used in mobile networks for basic applications such as order confirmation, mobile account payments, and short surveys.

Appendix C. Correspondence with Companies5

PortaOne

January 4 2023 – Letter sent from Citizen Lab to PortaOne

January 11 2023 – Email sent from PortaOne (via Fraser Litigation Group) to Citizen Lab

Dear Mr. Deibert.

We represent PortaOne, Inc.

Earlier today, PortaOne received a request for comment from CBC on a report that is apparently being published this Thursday by Citizen Labs, which “suggests PortaOne’s products and services are being used in the Communications Regulatory Authority of Iran’s mobile network interception system.” In response to a request for clarification from PortaOne, CBC provided a copy of your letter dated January 4, 2023, addressed to PortaOne (attached).

PortaOne had not seen your January 4, 2023, letter until being provided with same by CBC. The letter does not indicate how it was sent, but it was not received by PortaOne by email or at its mailing address. Accordingly, CBC’s inquiry has come as a complete surprise.

Later today, PortaOne received an inquiry from The Guardian, which indicated that it had received a copy of your report and the emails that it is based on.

PortaOne is a business founded by Ukrainian immigrants, with a significant base of operations in Ukraine and hundreds of employees who have greatly suffered as a result of Putin’s criminal attack on Ukraine, including Russia’s use of Iranian drones. PortaOne is proud to have a well-established pre and post-sales due diligence process for ensuring that it does not violate international sanctions or assist authoritarian regimes. PortaOne does not provide any products or services to or for use in Iran, it has never done business with Iran, Telinsol or Ariantel

To enable PortaOne to provide a meaningful response on the specific assertions in your report by the January 11, 2023 deadlines arbitrarily set in your letter, and by CBC and The Guardian, please immediately provide a copy of Report (or at least the portion dealing with PortaOne) and copies of the emails involving or referring to PortaOne upon which you rely.

We look forward to your immediate response.

If you have any questions, I can be reached at 604-343-3102.

Thanks,

Seva

Seva BatkinLL.B., B.Eng. / Fraser Litigation Group

Partner – Commercial and Estate Litigation*

T 604.343.3102 / F 604.343.3119

1100 – 570 Granville Street, Vancouver, BC V6C 3P1

www.fraserlitigation.com / Profile / LinkedIn

FRASER / BATKIN / TRIBE LLP

January 11 2023 – Public statement from PortaOne

January 11, 2023, 2.30 PM PST

PortaOne Provides Comments on the Upcoming Report by Citizen Lab

On January 10, 2023, PortaOne was contacted by CBC for comment on a report being released on January 12, 2023, by Professor Deibert of Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto. CBC did not provide PortaOne with a copy of the report but advised it asserts our products and/or services are being used by the Iranian authorities to intercept calls. CBC provided PortaOne with a letter dated January 4, 2023, to PortaOne from Professor Deibert requesting comments on his report.

PortaOne had not received the letter from Prof. Deibert, and was not aware of his report prior to being contacted by CBC. So that we could provide a meaningful response, we asked Prof. Deibert to provide a copy of the report and the documents relied on therein concerning PortaOne. We did not receive a response from Prof. Deibert despite the fact the report was provided to CBC and other media organizations.

We are a business founded by Ukrainian immigrants, with a significant base of operations in Ukraine and hundreds of employees who have greatly suffered as a result of Putin’s criminal attack on Ukraine, including Russia’s use of Iranian drones. We have not, and will not provide any products or services to or for use in or by Iran, including Iran’s telephone company, Ariantel.

We are proud to have a well-established due diligence process for ensuring that PortaOne does not violate international sanctions or assist authoritarian regimes. For example, immediately upon Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February, 2022, we terminated provision of products and services to Russian companies and cooperation with Russian technology companies.

PortaOne develops and provides two products and professional services therefore.

(1) PortaBilling, which is a telecom billing system. It manages customer information, calculates charges, and produces invoices. It does not process or interfere in any way with actual calls or other communications by customers. Customer profiles in the PortaBilling system do include a “Legal Intercept” flag, which may be set to indicate that a user is subject to legal surveillance. This flag was implemented in about 2005 to comply with United States Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). This is a purely informative flag. It does not enable or implement actual call interception or surveillance.

(2) PortaSIP, a Voice over IP (VoIP) system. It allows calls to be made between VoIP users and interface with a traditional phone system. It does not have any legal intercept / surveillance functionality, and cannot be used to process cellular network calls.

As we have not been provided with a copy of Professor Deibert’s report or the emails said to have been relied on by him, we cannot comment on any specific assertions in the report. With respect to the assertion that PortaOne supplied or supplies products or services to Iran used to intercept calls, this is categorically false. In fact, as a result of its vigilance, PortaOne prevented the sale of its software to an Iranian entity.

In 2018 and 2019, a sales manager, on his own initiative, engaged in business discussions with Ariantel, acting through Telesol, regarding PortaOne’s products. However, the license agreement for this deal submitted by the sales manager for approval by PortaOne’s management in September, 2019, was not with Ariantel, but with a Portuguese company.

On October 23, 2019, PortaOne received the first and only payment under this contract, which did not come from the Portuguese company, but from an unrelated entity. An immediate investigation by senior management revealed that the Portuguese company was a front for Ariantel. On October 28, 2019, PortaOne returned the payment and, on November 8, 2019, formally cancelled the contract with the Portuguese company, de-activated software license keys, and demanded that the company immediately uninstall, remove and/or delete any and all software downloaded from PortaOne.

PortaOne had not completed any integration services for the software supplied to the Portuguese company. We have since had no involvement whatsoever with or supplied products or services to this Portuguese company, Ariantel, Telsinol, or any other Iranian company or entity. Consequently, any suggestion that PortaOne has supplied software to Ariantel or to any other Iranian entity which is used to intercept or surveil calls in Iran is false.

A map on our website illustrating the geographic span of our customer base formerly mistakenly combined Iraq, where we have customers, and Iran, where we do not have any customers. That map has since been corrected.

PortaOne fully supports all efforts to prevent human rights abuses by authoritarian regimes, and we appreciate the work being done by Citizen Lab. We look forward to receiving Prof. Deibert’s report.

January 12 2023 – Letter sent from Citizen Lab (via Palaire Roland) to PortaOne (via Fraser Litigation Group)

Dear Mr. Batkin:

Re: Citizen Lab

We are litigation counsel to the Citizen Lab, and we are in receipt of your email dated January 10, 2023, directed to Dr. Ron Deibert, Director of the Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto. Please direct further correspondence on this matter to my attention.

Your email raises a number of issues that I would like to clarify.

First, you say that Prof. Deibert’s January 4, 2023 letter (the “January 4 Letter”) was not received by PortaOne, and that there is no indication of how it was sent. I note that the January 4 Letter includes PortaOne’s public “contact” email address. Attached to this letter is the email used by Prof. Deibert to send your client the January 4 Letter.

Second, your email states that PortaOne denies having done business in Iran. However, PortaOne’s publicly available website did, up until yesterday, identify 2-3 installations of its software in Iran. We observe that the current version of the PortaOne website no longer includes Iran as a country with such installations. Please ensure that all communications related to this change are preserved.

Third, we attach one of the emails involving PortaOne, which was reviewed by the Citizen Lab in preparing its report. In order to verify the authenticity of the emails from The Intercept, the Citizen Lab conducted a scan intended to assess the validity and integrity of the email evidence by verifying the following:

- The message domain key (DKIM) was valid, thus ensuring the cryptographic authentication of the message sender address and subject fields were not manipulated during transit;

- There is no malicious content in the email;

- The hops from sender and receiver servers are valid and registered; and

- Header values are valid and consistent (no anomalies).

We would be grateful if you could confirm that the PortaOne email address in the attached email is valid, and that you are retaining all correspondence related to that address.

In any event, we see now that PortaOne’s public statement from yesterday has evolved from the position set out in your email to Prof. Deibert. That statement will be included in the published version of Citizen Lab’s report.

Yours very truly,

PALIARE ROLAND ROSENBERG ROTHSTEIN LLP

January 13 2023 – Letter from PortaOne (via Fraser Litigation Group) to Citizen Lab 6

We are in receipt of your letter of January 12, 2023.

As you are aware from the statement issued by PortaOne on January 11, 2023 (the “PortaOne Statement”), PortaOne appreciates the work being done by Citizen Lab and Prof. Deibert. We were thus surprised that, instead of responding to our request for a copy of the Report to enable PortaOne to provide a meaningful response, Prof. Deibert engaged litigation counsel. Your letter does not explain his surprising unwillingness to engage with PortaOne directly and provide the Report, which he had already provided to the media (along with our request). We appreciate your confirmation that the PortaOne Statement will be included in the Report, and look forward to receiving a copy of same.

In response to the three points in your letter:

- Prof. Deibert’s January 4, 2023 letter included PortaOne’s mailing and email address, but, as we noted in our email, did not indicate a manner in which it was sent. In contrast, your letter included this information: “VIA EMAIL ([email protected])”. PortaOne had not received and seen the letter until it was provided with a copy of same by CBC. Subsequently, it was discovered that Prof. Deibert’s email was caught in PortaOne’s spam filter.

- PortaOne only found out about the assertion regarding its website on January 11, 2023, from a reporter’s question, and addressed it in the PortaOne Statement, the receipt of which you have confirmed. This assertion was not mentioned in Prof. Deibert’s letter.

- The email attached to your letter has already been addressed in the PortaOne Statement.

The assertion in the concluding paragraph of your letter that PortaOne’s statement had “evolved” from its position in our email to Prof. Deibert is inaccurate and inflammatory.

Yours truly,

Fraser / Batkin / Tribe LLP

Telinsol

January 4 2023 – Letter sent from Citizen Lab to Telinsol

January 11 2023 – Letter from Telinsol (via DLA Piper) to Citizen Lab

Dear Professor Deibert,

Re. Telinsol Ltd.

We have been contacted by Telinsol Ltd. (“Telinsol”) in connection with your letter of January 4, 2023.

We are in the process of finalizing our retainer but, given the deadline set in your letter, we thought it best to write to you forthwith to set out Telinsol’s position.

Telinsol Ltd. is a UK-based company established in 2015, and is globally active in various areas of IT and audio visual and technology-related services. Due to the nature of Telinsol’s business working with reputable global players, its legal and compliance team always makes sure that Telinsol fully abides by applicable laws and regulations.

Telinsol fully supports Iranians’ aspirations for democracy, freedom, and human rights — and particularly the rights of the Iranian people to freedom of expression and digital privacy. Telinsol also strongly condemns the brutal crackdown of the murderous Islamic regime against Iranian protestors.

In response to your letter, Telinsol flatly denies the allegation that it has been involved in activities that would in any way help digital espionage against Iranian citizens. In particular, the suggestion in your letter that Telinsol provides commercial services to support Iran’s Legal Intercept requirements of mobile surveillance, service control and account management is entirely false and any publication of such an allegation would cause irreparable harm to Telinsol, as well as to the reputation of its past and present clients.

In the result, Telinsol strongly urges Citizen Lab to eliminate any reference to Telinsol in its report. While Telinsol greatly appreciates the impactful work done at the Citizen Lab and fully supports your goal of preventing digital espionage against civil society, Telinsol will not hesitate to avail itself of all available legal remedies in response to a defamatory publication by Citizen Lab.

Sincerely,

DLA Piper (Canada) LLP

January 13 2023 – Letter from Telinsol (via DLA Piper) to Citizen Lab

Dear Professor Deibert,

Re: Telinsol Ltd.

I write to follow up on my letter to you of January 11, 2023.

While Telinsol continues to review the hacked e-mails at issue, I have been asked to convey to you the fact that those hacked e-mails evidence a relationship between Ariantel and PortaOne which pre-dates the involvement of Telinsol. The hacked e-mails further evidence Telinsol entertaining an initial enquiry by Ariantel and PortaOne and thereafter entering a due diligence process — a due diligence process that ended in September, 2019 with Telinsol rejecting involvement in the project.

It is Telinsol’s understanding that any activities that thereafter continued were with a Portugal-based company named Magicalcharacter.

I again reiterate the irreparable harm that will be suffered by Telinsol if Citizen Lab publishes inaccurate information about Telinsol in its report.

Sincerely,

DLA Piper (Canada) LLP

January 14 2023: Letter from Citizen Lab to Telinsol

Dear Tudor Carsten:

Re: Citizen Lab

We are counsel to the Citizen Lab, and we write in response to your letters of January 11 and 13, 2023. Please direct future correspondence on this matter to my attention.

We appreciate that you have just been retained, and that you may not have had an opportunity to be fully briefed by your client on this matter. To assist, we enclose an example email showing direct communications between Telinsol Ltd. and an Iranian telecommunications provider, in which they discuss the technical requirements of the Iranian regime’s surveillance infrastructure, and how your client might assist in same.

The authenticity of these emails—which are dated in 2021, two years after you say that Telinsol Ltd. stopped communicating with its Iranian counterparty—has been verified by the Citizen Lab in the following manner:

- The message domain key (DKIM) was valid, thus ensuring the cryptographic authentication of the message sender address and subject fields were not manipulated during transit;

- There is no malicious content in the email;

- The hops from sender and receiver servers are valid and registered; and

- Header values are valid and consistent (no anomalies).

We also note that Telinsol Ltd., and its senior employees, appear to be in the process of scrubbing their public Internet profiles to remove references linking their work to Iran.

In light of your allegations of defamation and reference to considering “all available legal remedies”, we trust that your client is preserving all communications, internal and external, related to its work in Iran. Please also confirm that Telinsol Ltd. and their employees have saved copies of any online content that they changed after learning of Citizen Lab’s work.

Yours very truly,

PALIARE ROLAND ROSENBERG ROTHSTEIN LLP

PROTEI

January 4 2023 – Letter from Citizen Lab to PROTEI

- The document also notes that “[t]his is a totally new project and there are no running services at the moment.”↩︎

- Infrastructure search engines Censys and Shodan showed fingerprints of PROTEI equipment present in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Russia when searched on 2022-11-30, and showed as an equipment vendor in Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan based on RAEX IR.21 reporting data.↩︎

- PortaOne maintains a public wiki that includes discussions around compliance with lawful intercept requirements worldwide, including a 2017 discussion on compliance with Russia’s SORM (System for Operative Investigative Activities) system.↩︎

- Note that in PortaOne’s second response to the Citizen Lab (see Appendix C), the company explains that it did contract with a Portuguese company and, under this contract, received a single payment from an unrelated entity. This payment prompted an investigation by senior management and led to the discovery that the Portuguese company was a front for Ariantel.↩︎

- Formatting for this section was updated on January 18th, 2023.↩︎

- This letter was added after publication on January 16th, 2023.↩︎