Key Findings

- Introducing Paragon Solutions. Paragon Solutions was founded in Israel in 2019 and sells spyware called Graphite. The company differentiates itself by claiming it has safeguards to prevent the kinds of spyware abuses that NSO Group and other vendors are notorious for.

- Infrastructure Analysis of Paragon Spyware. Based on a tip from a collaborator, we mapped out server infrastructure that we attribute to Paragon’s Graphite spyware tool. We identified a subset of suspected Paragon deployments, including in Australia, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Israel, and Singapore.

- Identifying a Possible Canadian Paragon Customer. Our investigation surfaced potential links between Paragon Solutions and the Canadian Ontario Provincial Police, and found evidence of a growing ecosystem of spyware capability among Ontario-based police services.

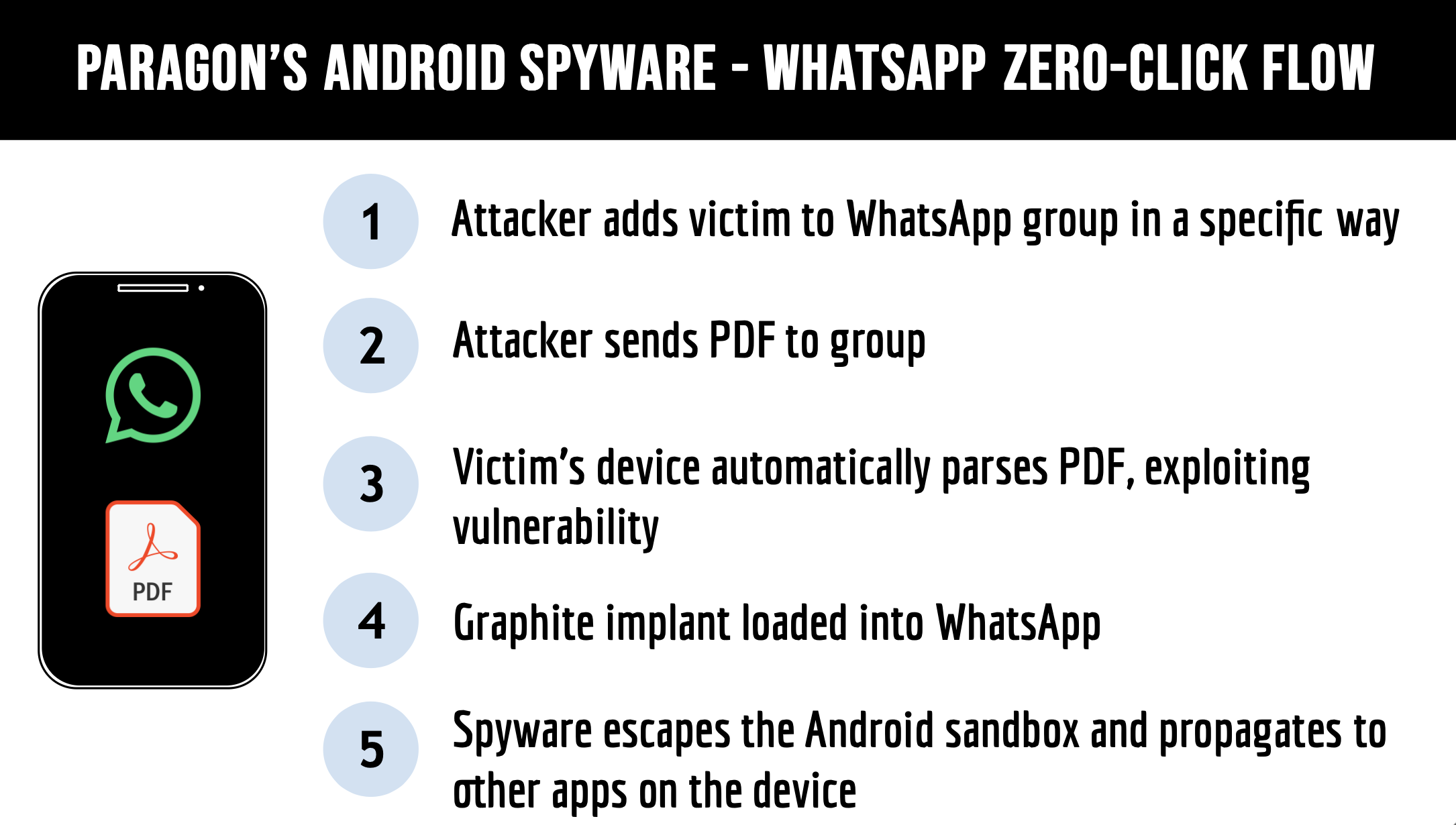

- Helping WhatsApp Catch a Zero-Click. We shared our analysis of Paragon’s infrastructure with Meta, who told us that the details were pivotal to their ongoing investigation into Paragon. WhatsApp discovered and mitigated an active Paragon zero-click exploit, and later notified over 90 individuals who it believed were targeted, including civil society members in Italy.

- Android Forensic Analysis: Italian Cluster. We forensically analyzed multiple Android phones belonging to Paragon targets in Italy (an acknowledged Paragon user) who were notified by WhatsApp. We found clear indications that spyware had been loaded into WhatsApp, as well as other apps on their devices.

- A Related Case of iPhone Spyware in Italy. We analyzed the iPhone of an individual who worked closely with confirmed Android Paragon targets. This person received an Apple threat notification in November 2024, but no WhatsApp notification. Our analysis showed an attempt to infect the device with novel spyware in June 2024. We shared details with Apple, who confirmed they had patched the attack in iOS 18.

- Other Surveillance Tech Deployed Against The Same Italian Cluster. We also note 2024 warnings sent by Meta to several individuals in the same organizational cluster, including a Paragon victim, suggesting the need for further scrutiny into other surveillance technology deployed against these individuals.

1. Background: Paragon Solutions

This section provides a brief background on Paragon’s corporate structure.

Paragon Solutions Ltd.

Paragon Solutions Ltd. was established in Israel in 2019. The founders of Paragon include Ehud Barak, the former Israeli Prime Minister, and Ehud Schneorson, the former commander of Israel’s Unit 8200. Paragon sells a spyware product called Graphite, which reportedly provides “access to the instant messaging applications on a device, rather than taking complete control of everything on a phone,” like NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware.

According to a Forbes report from 2021, a senior executive at Paragon said the company would only sell to government customers who “abide by international norms and respect fundamental rights and freedoms” and that “authoritarian or non-democratic regimes would never be customers.”

Paragon Solutions (US) Inc.

Paragon Solutions (US) Inc. was established as a Delaware corporation in March 2021. In October 2022, Paragon US obtained a certificate to conduct business in Virginia.

Paragon US’s senior leadership is composed of American personnel with links to the US government, including a CIA veteran, a former service member and Navy program director that also worked at Twitter, and a former director of contracts at the defense contractor L3Harris.

Paragon Parent Inc.

According to corporate records, on December 13, 2024, all shares in Paragon Israel were transferred to a US company, Paragon Parent Inc. This deal was reportedly worth $500 million upfront, with an additional $400 million payable if Paragon Israel reached set performance targets.

Paragon Parent Inc. was registered in Delaware on October 7, 2024. Shareholder information for Paragon Parent is not publicly available, though reporting suggests that US private equity firm AE Industrial Partners (AEI) acquired Paragon Israel with the intention of merging it with US cybersecurity company, REDLattice Inc.1 The reported merger further bolsters Paragon’s high-ranking intelligence and military connections. According to recent SEC filings, board members of the REDLattice company, REDL Ultimate Holdings (a company linked to RedLattice according to corporate records), include Andrew Boyd, a former senior executive at the CIA and US Air Force, and James McConville, the former Chief of Staff of the US Army.

Paragon’s US Business

While the specific nature of the relationship between Paragon Solutions (US) Ltd. and Paragon Parent Inc. are hard to discern, the presence of Paragon Solutions in the US marketplace is noteworthy. In 2022, the New York Times reported that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had used Paragon’s Graphite spyware. On the other hand, recent contracting between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Paragon Solutions was reportedly paused under White House review at the end of 2024. Notably, at least 36 civil society organizations expressed concern and called for transparency after this contract was first reported by Wired. The status of that contract is currently unknown.

2. Mapping Paragon’s Infrastructure

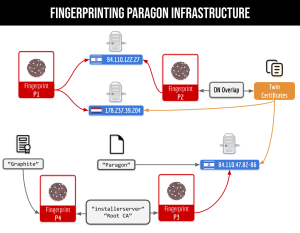

Our initial investigation into Paragon began with mapping infrastructure that we believe Paragon and its government customers use to carry out or support spyware attacks. We find that this infrastructure included cloud-based servers likely rented by Paragon and/or its customers, as well as servers likely hosted on the premises of Paragon and its government customers.

Tier 1: Victim-Facing Servers

In 2024, we received a tip from a collaborator about a single piece of infrastructure: a domain name pointing to a server that also returned several distinctive self-signed TLS certificates. The certificates had multiple curious elements, including various pieces of missing information and a distinctive naming scheme. We developed Fingerprint P1 for these certificates:

Fingerprint P1:

parsed.validity_period.length_seconds=31536000 and

parsed.extensions.subject_alt_name.dns_names=/.+/ and not

parsed.extensions.subject_alt_name.uniform_resource_identifiers=/.+/ and not

parsed.extensions.key_usage.value=[0 to 255] and not

parsed.extensions.extended_key_usage.server_auth=`true` and

parsed.subject_dn=/O=[a-z0-9\-\.]+, CN=[a-z0-9\-\.]+/ and

(parsed.issuer_dn=/O=[a-z0-9\-\.]+, CN=[a-z0-9\-\.]+/ or not

parsed.issuer_dn=/.+/) and ((parsed.extensions.subject_key_id=/.+/ and parsed.extensions.authority_key_id=/.+/) or

(not parsed.extensions.subject_key_id=/.+/ and not parsed.extensions.authority_key_id=/.+/)) and not

parsed.extensions.basic_constraints.is_ca=true and not

parsed.extensions.basic_constraints.is_ca=false and labels=`unexpired`

Using this fingerprint, we found 150 related certificates on Censys2 with approximately half of the certificates actively served on IP addresses. The IP addresses appear to be primarily sourced from cloud-based server rental companies. The infrastructure appears to be consistent with a dedicated command and control infrastructure (“Tier 1”). We would expect victim devices to communicate with this infrastructure under certain conditions.

Pivoting to Tier 2: Paragon and Customer Endpoints

While conducting our investigation, we observed two Tier 1 IPs (matching Fingerprint P1) that also returned a different type of certificate:

| IP | Other Certificate | Nature of Overlap |

| 84.110.122[.]27 | C=AU, ST=Some-State, O=Internet Widgits Pty Ltd, CN=forti.external-Staging-02.com | Certificate observed contemporaneously with Tier 1 certificates between July and September 2023. Afterwards, only Tier 2 certificates observed. |

| 178.237.39[.]204 | C=AU, ST=Some-State, O=Internet Widgits Pty Ltd, CN=awake-wood.io | Certificate observed approximately two months after Tier 1 certificate was observed on the IP. |

Table 1. Fingerprint P1 results that return a different certificate

The first IP, 84.110.122[.]27, appears to be a static IP address geolocated to Israel. The IP address returned the forti.external-Staging-02[.]com certificate until January 2024. Between July 2023 and September 2023, it returned both the aforementioned forti.external-Staging-02[.]com certificate as well as several Tier 1 certificates. We developed the P2 fingerprint for this certificate:

Fingerprint P2:

parsed.issuer.organization=”Internet Widgits Pty Ltd” and

parsed.extensions.subject_alt_name.dns_names=/.+/ and

parsed.extensions.key_usage.value=96

When we checked, Censys recorded 47 certificates3 matching Fingerprint P2. The results included a certificate with the exact same subject and issuer DN as the certificate returned by the second IP, 178.237.39[.]204. However, the certificate returned by 178.237.39[.]204 had a different hash. We further noted that in fact, all 47 certificates matching Fingerprint P2 had a “twin” certificate not matching Fingerprint P2, but with identical issuer DN, and either identical subject DN, or a subject DN identical except with the addition of a subdomain “forti” to the common name. We define certificates matching Fingerprint P2, as well as their twins, to be Tier 2 certificates.

The IPs that returned these certificates were often not cloud-based servers (as with Tier 1 infrastructure), but were instead IPs procured from local wireline telecommunications operators. Thus, we suspected that they might be run directly from Paragon and customer premises.

Tier 2 Nodes in Israel Have Links to “Paragon”

Examining Censys records shows that at various times, a range of static IPs in Israel (84.110.47.82 – 84.110.47.86) returned Tier 2 certificates:

| IP | Subject Common Name | Dates |

| 84.110.47.82 | forti.paraccess[.]com | 2021-02-10 – 2025-01-01 |

| 84.110.47.83 | forti.paraccess[.]com | 2021-01-21 – 2024-12-31 |

| 84.110.47.84 | – | – |

| 84.110.47.85 | modern-money[.]org | 2024-09-10 – Present |

| 84.110.47.86 | ancient-thing[.]it | 2022-03-09 – 2024-01-29 2024-05-10 – Present |

Table 2. Static IPs in Israel returning Tier 2 certificates

IPs in the same range also returned self-signed certificates matching Fingerprint P3:

Fingerprint P3:

parsed.issuer_dn=”C=US, ST=CA, CN=Root CA”

Censys’ Certificates dataset records a total of eight certificates matching Fingerprint P3 (though the Hosts dataset records additional ones that are missing from the Certificates dataset, perhaps due to Censys data loss around this time).

| IP | Subject Common Name (and Port) | Dates |

| 84.110.47.82 | firewall (4443/TCP) | 2021-02-09 – 2021-02-18 |

| 84.110.47.83 | – | – |

| 84.110.47.84 | milka (443/TCP)

Gateway (443/TCP) installerserver (4443/TCP) dashboard (1443/TCP) |

2020-11-10 (or earlier) – 2021-01-09 |

| 84.110.47.85 | dashboard (1443/TCP)

installerserver (4443/TCP) |

2020-11-24 (or earlier) to 2021-01-09 |

| 84.110.47.86 | rproxyworkers (4432/TCP)

firewall (4443/TCP) dashboard (2443/TCP) |

2020-11-10 (or earlier) to 2021-01-08 |

Table 3. The same range of static IPs in Israel returned certificates matching Fingerprint P3.

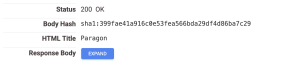

In all cases we identified, after the “dashboard” certificate was returned, a page with the title “Paragon” was returned:

A Link to “Graphite”

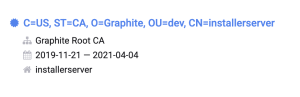

We looked for related certificates with the same “installerserver” name using Fingerprint P4:

Fingerprint P4:

parsed.subject.common_name=”installerserver” and

parsed.issuer.common_name=”Root CA”

This yielded only one certificate not included in the results of Fingerprint P3: a certificate apparently created in November 2019 with the organization name “Graphite”.

It is not clear which IP address returned this certificate, as historical Censys data for that time period appears to be incomplete.

Attribution of Infrastructure to Paragon

In summary, strong circumstantial evidence supports a link between Paragon and the infrastructure we mapped out. The infrastructure we found is linked to webpages entitled “Paragon” returned by IP addresses in Israel (where Paragon is based), as well as a TLS certificate containing the organization name “Graphite”, which is the name of Paragon’s spyware, and the common name “installerserver” (Pegasus, a competitor spyware product, uses the term “Installation Server” to refer to a server designed to infect a device with spyware).

Tier 2 Nodes Highlight Several Potential Paragon Customers

We identified other interesting IPs apparently procured from local telecom companies that returned Tier 2 certificates. Because the IPs appear to belong to local telecom companies rather than cloud-based server rental companies, we suspect these IPs belong to Paragon’s customer deployments. We also note that the first letter of each customer’s apparent “codename” matches the first letter of the country associated with the customer’s IP address (except in the case of Israel).

| Subject Common Name | IP Returning Certificate | IP in Country |

| external-astra[.]com | 120.150.253.xxx | Australia |

| internal-Abba[.]com | 150.207.167.xxx | Australia |

| external-cap[.]com | 67.69.21.xxx | Canada |

| external-drt[.]com | 195.249.167.xxx | Denmark |

| forti.external-muki[.]com | 31.168.219.xxx | Israel |

| external-cag[.]com | 217.27.58.xxx | Cyprus |

| forti.external-sht-prd-4[.]com

forti.external-shotgun3[.]com forti.external-sht[.]com forti.external-Sht_prd_2[.]com |

58.185.8.xxx | Singapore |

| forti.internal-stg[.]com | 61.16.116.xxx | Singapore |

Table 4. Some suspected Paragon customer deployments.

In addition, we noted that Tier 2 certificates were returned by at least eleven IPs that geolocate to a German datacenter of Digital Realty, a datacenter holding company. The IPs were all registered to a single “Digital Realty DE IP Customer” ID, and certificates returned included various codenames, like “nelly”, “soundgarden”, “slash”, “galaxy”, and “chance”. Additionally, the use of names such as “p-internal”, “p-external”, and “access” and “management” leads us to believe that Digital Realty’s customer may be Paragon. More recently, Paragon deployments appear to use more ambiguous codenames in the form of fictitious domains such as “anxious-poet” or “sincere-cookie”.

Note that this methodology cannot enumerate all customers, as no Internet scanning service (e.g., Censys) has a complete historical view of the Internet at all times. Furthermore, some customers likely took measures to prevent their infrastructure from being exposed in Internet scans. For example, Italy is an admitted Paragon customer (see: Section 4).

“Cap”: Registration Information Raises Canadian Questions

The IP address for the Canadian customer Cap was delegated to ARIN customer C06874702, named “Integrated Communications.” We searched ARIN’s WHOIS data and found five additional “Integrated Communications” customers in Canada, all in Ontario (C02423261, C07940612, C09095096, C10862989, C10948330). Each customer controls a single range of 8 or 16 IP addresses.

The address of one of the customers, C10862989, matches that of the “Ontario Provincial Police – General Headquarters.” The other customer addresses include what appear to be a shared warehouse, a strip mall, a brewery, and an apartment. The small number of customers named “Integrated Communications”, the fact that all such customers in Canada are in Ontario, and the use of the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) address for one of them, suggests the OPP as a potential Paragon Solutions customer.

Canadian Law Enforcement’s History with Surveillance

The OPP has previously been linked to other instances involving the procurement or use of controversial surveillance technologies. In 2019, the Toronto Star reported that for several years the OPP was the only police service in Canada to procure cell site simulator technology (i.e., “Stingray” equipment) which can be used to intercept private communications. In 2020, The Citizen Lab reported that the OPP developed and deployed technology to scrape communications from private, password-protected online chatrooms without obtaining judicial authorization for the mass interceptions.

In 2022, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Canada’s national police force, disclosed that the RCMP had been using spyware from an unnamed vendor. The RCMP referred to the spyware as an “On-Device Investigative Tool” (ODIT)4, and said it had used ODITs in 32 investigations between 2017 and 2022. The RCMP did not consult with the public, or the Privacy Commissioner of Canada on its use of ODITs. Canada’s Public Safety Minister refused to disclose which vendors supplied RCMP with ODITs, and did not deny that other government agencies might also use ODITs.

Public records obtained and reviewed by The Citizen Lab suggest there is a growing ecosystem of spyware capability among Ontario-based police services. According to public court records obtained by The Citizen Lab, the OPP used the RCMP’s ODITs in the course of a 2019 investigation to infect a mobile phone for remote interception of private communications. A 2023 judgment from the Superior Court of Justice in Toronto describes a joint investigation between the Toronto Police Service and the York Regional Police Service where investigators had considered the use of an ODIT. The Citizen Lab also obtained an additional public court record (a 2023 search warrant application) prepared by the Toronto Police Service (TPS), which reveals that the TPS has independently obtained ODIT software from an unknown source. The application sought authorization to use ODIT software to remotely intercept cellular communications sent through encrypted instant messaging applications.

In the course of the preparation of this report, we have also learned through informal consultations of other cases that have been–or currently are–before the courts in Ontario involving other police services that now also possess or have sought authorization to deploy ODITs, including the OPP, York Regional Police Service, Hamilton Police Service, and Peel Regional Police Service. The apparent expansion of spyware capabilities to potentially multiple police services across Ontario reflects a widening gap in public awareness surrounding the extent to which mercenary spyware is being deployed in Canada.

3. WhatsApp’s Paragon Investigation

We shared details about our mapping of Paragon’s infrastructure (Section 2) with Meta, because we believed that WhatsApp might be used as an infection vector. Meta told us that these details were pivotal to their ongoing investigation into Paragon. Meta shared information with WhatsApp that led them to identify, mitigate, and attribute a Paragon zero-click exploit. On January 31, 2025, WhatsApp sent notifications to approximately 90 WhatsApp accounts they believed were targeted with Paragon’s spyware, including journalists and members of civil society.

The Citizen Lab coordinated with WhatsApp to ensure that targets in civil society were offered additional support and optional forensic analysis. In Italy, several individuals that chose to participate in forensic analysis with the Citizen Lab spoke out publicly about receiving notifications from WhatsApp (Section 4). They include a journalist and multiple members of civil society that work in organizations involved in the rescue of refugees and migrants at sea.

4. Paragon Targets: The Italian Connection

This section describes our forensic analysis of the devices of targets who received Paragon notifications from WhatsApp, as well as our analysis of a potentially related iPhone case.

Multiple WhatsApp notification recipients in Italy elected to participate in The Citizen Lab’s research program and have The Citizen Lab forensically analyze their devices. They are identified below, with their consent:

- Francesco Cancellato is the Editor in Chief of Fanpage.it, an Italian online news outlet known for investigative journalism and reporting on political topics. The outlet has reported on connections between extremist elements and Italian Prime Minister Meloni’s party.

- Luca Casarini is the founder of Mediterranea Saving Humans, an organization known for rescuing migrants from the Mediterranean Sea. Mr. Casarini is well-known for his criticism of the Meloni government’s treatment of migrants. Mr. Casarini is also a personal friend of Pope Francis.

- Dr. Giuseppe “Beppe” Caccia is an Italian scholar and co-founder of Mediterranea Saving Humans. Dr. Caccia works closely with Mr. Casarini.

Forensically Confirming Android Paragon Infections

In the course of our investigation into Paragon we obtained BIGPRETZEL, an Android forensic artifact that we believe uniquely identifies infections with Paragon’s Graphite spyware. We analyzed the Android devices of the three individuals identified above. Based on their receipt of the WhatsApp notification, we believe all were targeted with Paragon spyware. We found traces of BIGPRETZEL on two devices. WhatsApp has also confirmed to The Citizen Lab that they believe that BIGPRETZEL is attributable to a Paragon spyware infection, and provided us with the following statement:

Given the sporadic nature of Android logs, the absence of a finding of BIGPRETZEL on a particular device does not mean that the phone wasn’t successfully hacked, simply that relevant logs may not have been captured or may have been overwritten. We also believe that the forensic indicators we have surfaced during this analysis may not fully capture the complete retrospective timeframe of infections for the same reasons. There may have been infections prior to the period observed, but not captured in the logs. Our forensic analysis is ongoing.

Dr. Caccia’s phone showed traces of BIGPRETZEL at several times, indicating that Paragon’s spyware was running on or around these times:

2024-12-22 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2024-12-26 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2025-01-03 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2025-01-13 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2025-01-23 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2025-01-28 – BIGPRETZEL present.

2025-01-31 – BIGPRETZEL present.

Additionally, analysis of Dr. Caccia’s phone showed evidence that the spyware had also infected two other apps on the device, including a popular messaging app. We have shared forensic indicators with the developers of that app, who confirm that their investigation is ongoing.

Mr. Casarini’s phone showed traces of BIGPRETZEL on at least one date:

Given limited available indicators, we were unable to determine if the spyware had loaded itself into other apps on Mr. Casarini’s device, but cannot exclude the possibility.

A Related iPhone Spyware Victim: Is it Paragon?

On November 13, 2024 (approximately two-and-a-half months before the WhatsApp notifications), David Yambio–a close associate of Mr. Casarini and Dr. Caccia–was notified by Apple that his iPhone had been targeted with mercenary spyware.

Mr. Yambio is an Italy-based founder of the organization Refugees in Libya. Mr. Yambio’s work focuses on advocating for lifesaving efforts for migrants that cross the Mediterranean, and on helping victims seek justice and accountability for abuses committed in Libya. He is a former child soldier kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army who eventually escaped and was able to reach Europe where he claimed asylum. During this journey, he was tortured while in detention in Libya.

After he received the Apple notification, Mr. Yambio contacted digital security expert Artur Papyan of Cyber HUB-AM for assistance. Mr. Papyan performed an initial screening of the device supported by The Citizen Lab which identified potential anomalies. We immediately began an investigation into Mr. Yambio’s case, and Mr. Papyan provided extensive support in collecting forensic artifacts from the device.

While our investigation was ongoing, multiple close associates of Mr. Yambio also received notifications from WhatsApp concerning Paragon targeting of their Android devices, including Mr. Casarini and Dr. Caccia.

Analysis of Mr. Yambio’s Device

We found that Mr. Yambio’s device showed clear signs of implausible CloudKit activity relating to the appleaccountd process on 13 June 2024. We call this activity SMALLPRETZEL. The device did not test positive for any indicators we link to other spyware types, including NSO Group’s Pegasus, Intellexa’s Predator, QuaDream’s Reign, Triangulation, and others.

With Mr. Yambio’s consent, we shared forensic details with Apple, including SMALLPRETZEL. Apple confirmed to us that our forensic findings matched an attack that they had identified, investigated, and mitigated in iOS 18. Apple provided us with the following statement:

“Mercenary spyware attacks like this one are extremely sophisticated, cost millions of dollars to develop, often have a short shelf life, and are used to target specific individuals because of who they are or what they do. After detecting the attacks in question, our security teams rapidly developed and deployed a fix in the initial release of iOS 18 to protect iPhone users, and sent Apple threat notifications to inform and assist users who may have been individually targeted. While the vast majority of users will never be the victims of such attacks, we sympathize deeply with the small number of users who are, and we continue to work tirelessly to protect them.”

Links to Paragon?

While it is clear that an attempt was made to infect Mr. Yambio’s device with spyware, we cannot yet establish a conclusive technical link between SMALLPRETZEL and any particular type of spyware. That said, we note there are some contextual factors that suggest the spyware used against Mr. Yambio may have also been Paragon’s Graphite. In particular, Mr. Yambio works closely with the cluster of forensically confirmed Paragon targets and WhatsApp-notified individuals. While we are not attributing this attack to Paragon at this time, we continue to investigate this case.

Additional Prior Targeting

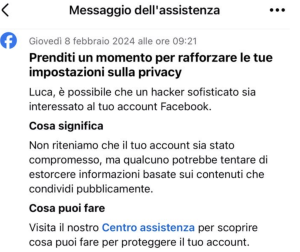

Mr. Casarini also received a notification on February 8, 2024, from Meta concerning government-backed targeting. Father (Don) Mattia Ferrari, an Italian priest and the chaplain of Mediterranea Saving Humans, also received a Meta notification on the same day as Mr. Casarini. Mr. Ferrari, like Mr. Casarini, is a personal friend of Pope Francis and manages the group’s relationship with the Bishops’ Conference of Italy.

The English translation of the above message (Figure 7):

“Take a moment to strengthen your privacy settings. Luca, it is possible that a sophisticated hacker is interested in your Facebook account.

What it means: We do not believe that your account was compromised, but someone could try to extract information based on the contents that you share publicly.

What you can do:Visit our Help Center to find out what you can do to protect your account.”

Meta published a wide-ranging report entitled “Countering the Surveillance-for-Hire Industry” at the same time as the notifications. The report named several vendors whose technology, including spyware, was used against targets in Italy.

The notifications are interesting because they expand the time window of potential targeting with spyware, and suggest that multiple types of spyware may be used as part of interrelated surveillance operations.

Targeting Civil Society Sea Rescue Operations: Notes on A Possible Cluster

Like elsewhere, migration and refugee issues are a contentious topic in Italy. Italy’s geographic location makes it a natural first landing point for people fleeing from conflicts and poverty in the Sahel and Sub-Saharan regions.

Migrants and refugees typically use improvised or precarious boats to make this journey, which has led to numerous tragic shipwrecks. Over the past decade, more than 30,000 migrants and refugees have died trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea. Civil society organizations conduct humanitarian search and rescue (SAR) operations with the goal of reducing the number of fatalities and bringing migrants and refugees to safety at the closest landing port, which is often in Italy.

Over the past two years, humanitarian organizations operating in the area have faced increasing pressure from the Italian authorities. For example, in early 2023, the Italian Parliament passed a law put forward by the government increasing the restrictions on SAR operations. The law was denounced by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights as “effectively punish[ing] both migrants and those who seek to help them”.

Potential Relationship Between the Various Paragon Targets

It is clear that Mr. Casarini, Dr. Caccia, and Mr. Yambio all work closely together. They have told The Citizen Lab that they believe that they have been targeted based on this association, and their collective work and criticism of the Italian government’s handling of specific issues concerning migration. Italian media has also speculated about the specific implications of the timing of the targeting and its relationship to their advocacy work.

While our forensic findings include dates of infection for each individual, as we note above (see: Forensically Confirming Android Paragon Infections), targeting may in fact have extended prior to the dates we have found. We note, for example, the notification sent to Mr. Casarini and Mr. Ferrari by Meta in February 2024 regarding targeting with what is likely a different surveillance technology (see above: Additional Prior Targeting)

Italy’s Conflicting Response to the Paragon Revelations

The response from the Italian government to the Paragon situation has evolved over time. In a familiar pattern that began with denials, the Italian government has been forced to acknowledge contracts with Paragon Solutions. However, the government’s response was marked by a lack of clarity, transparency and specificity about the cases reported thus far.

- On February 6, 2025, the Italian government issued a statement denying knowledge of the affair.

- Later that night, The Guardian published a report stating that Paragon had cancelled their contract with two Italian customers. The report indicated that Paragon had received unsatisfactory answers to their questions about the Italian cases.

- A second report from Haaretz indicated two Italian Paragon customers: a law enforcement entity and an intelligence entity.

- On February 12, 2025, the Italian Minister for Relations with Parliament publicly confirmed that the government was a Paragon customer, claiming that all the related systems were still active, while still denying that the national intelligence services had spied on the known targets.

- On the same day, the director of the external intelligence service (AISE) confirmed that Paragon’s Graphite spyware had been deployed by his agency on multiple occasions, and listed them to the parliamentary committee overseeing the intelligence services in a classified hearing. He denied the agency having spied on journalists and activists.

- On February 14, 2025, the Italian government stated that, together with Paragon, they had jointly agreed to suspend the deployment pending an investigation.

- On February 19, 2025, the government issued a letter to Parliament stating that it could not respond to parliamentary inquiries on the Paragon affair, as any information not yet disclosed should have been considered classified.

- In the parliamentary session that ensued, however, the Minister of Justice contradicted that statement, responding to the inquiries put forth by opposition parties and stating that no agency reporting into his Ministry had stipulated a contract with Paragon.

A History of Mercenary Spyware in Italy

Italy is perhaps best known as a producer of, rather than a customer of, mercenary spyware. A March 2023 report noted several mercenary spyware firms operating from Italy at the time, including AREA, RCS, SIO, INNOVA, Memento Labs (formerly known as Hacking Team), Raxir, Negg, and Cy4gate.

The recent Venice Commission report on the regulation of spyware in the European Union notes that the use of spyware is regulated in Italian law. Its framework for criminal proceedings limits its use to “particularly serious offences (such as, for example, mafia-type criminal association),” or in limited circumstances, “for offences committed by public officials against the public administration” that carry a maximum penalty of at least five years’ imprisonment. The report notes that, among other constraints, authorization for targeted surveillance measures must be obtained from the judiciary under domestic law in Italy.

Conclusion: You Can’t Abuse-Proof Mercenary Spyware

Paragon Solutions is a relatively new entrant in the mercenary spyware ecosystem. Like many other mercenary spyware companies, Paragon appears to have aggressively sought access to the US market. There are many reasons for this emphasis on access to the US market: it is large, lucrative, and spyware companies have a track record of considering having US customers as a kind of protection.

In the wake of action from the White House and Congress to pump the brakes on mercenary spyware proliferation, the incentives likely grew for commercial spyware companies to seek the government’s ‘good side.’ This has clearly included insider lobbying and public messaging that seeks to portray these companies as aligned with US priorities.

Paragon’s communications strategy focuses on framing itself as taking a different approach than NSO Group with respect to its client base, technology, and safeguards. Much of this marketing seems focused on seeking to persuade the US that the company aligns with US interests.

Paragon specifically courts media attention with claims that by only selling to a select group of governments, they can avoid the abuse scandals plaguing their peers. The implicit message: if you do not sell to autocrats, your product will not be used recklessly and in anti-democratic ways. History, however, shows us that this is not always the case. Many democratic states have histories of using secret surveillance powers and technologies against journalists and members of civil society.

Mercenary spyware is no exception, with multiple democracies deploying spyware against journalists, human rights defenders, and other members of civil society. Indeed, organizations working against the proliferation and abuse of spyware, including the Citizen Lab, have warned that the temptation to use this technology in a rights-abusing way is so great that, even in democracies, it will be abused.

Overall, the cases described in this report suggest that Paragon’s claims of having found an abuse-proof business model may not hold up to scrutiny. We acknowledge that this report does not seek to cover the totality of Paragon cases, but rather a set of cases where targets have chosen to come forward at this time and in our report. However, the pattern in these cases challenges Paragon’s marketing approach which has claimed that the company would only sell to clients that “abide by international norms and respect fundamental rights and freedoms.”

This report is a first step towards understanding the scope and scale of potential Paragon spyware abuses. The 90-some targets notified by WhatsApp likely represent a fraction of the total number of Paragon cases. Yet, in the cases already investigated, there is a troubling and familiar pattern of targeting human rights groups, government critics, and journalists.

The Twilight of Forensics?

In traditional cases of mobile compromise, an attacker exploits vulnerabilities on a device and activates the functionality of their spyware by invoking their own app or process. This app or process must then perform certain privileged actions on the device, which may leave side effects that a forensic analyst can later observe.

Paragon takes a different approach: in a technique reminiscent of Android spyware deployed by the Poison Carp threat actor, Paragon appears to silently load their spyware into the device’s existing legitimate apps and processes, which serve as the spyware’s unwitting hosts. This approach is ultimately less likely to leave obvious forensic evidence that an analyst with device-in-hand can easily find; an analyst would probably need a detailed understanding of the workings of each host app in order to reach a conclusion that the device was compromised.

Paragon’s approach has been likened to “hypersonic weapons, in cybersecurity terms”, but it is better understood as a tradeoff. Their focus on targeting legitimate apps is certainly a difficulty multiplier for forensic analysis, but it is also likely to multiply the number of entities that have visibility into Paragon’s activities, given that app developers collect diagnostic data, crash reports, and other telemetry from their apps. This speaks to the value of collaboration between civil society, forensic experts, and tech platforms’ threat intelligence teams.

Notifications and the Spyware Accountability Ecosystem: Critical Ingredients

When WhatsApp chose to notify Paragon targets and be explicit with their attribution, they performed an important service, as warnings to users about mercenary spyware targeting are a critical component of the growing accountability ecosystem around mercenary spyware abuses.

Today, several of the largest companies have increasingly mature notification procedures and language. These notifications often lead to cases flowing to civil society organizations and helplines organically. This assistance is especially important as companies like Paragon shift tactics in ways that may be more visible to app developers, and perhaps less so to forensic analysts.

The cases described in this report would have largely remained undiscovered without WhatsApp and Apple notifying users. The case of Mr. Yambio came to our attention thanks to Cyber Hub-AM, who he contacted after receiving a notification from Apple. This case also points to the importance of the ecosystem of organizations working on mercenary spyware.

Time for Questions

We note media reports that Paragon’s Graphite spyware maintains “detailed logs” on the premises of government customers. Given the concerns about the publicly-known targets in Italy, these logs should be a natural target of any official investigation into reports of misuse. They might also provide a better understanding of the scope and scale of use in Italy.

Even if mercenary spyware has been acquired for a primary purpose, such as investigating organized criminal groups, experience shows that, over-time, the temptation to use these powerful technologies for political purposes is substantial. Mexico’s case is a strong illustration of this phenomenon, with Pegasus spyware abuses linked to two successive governments.

While investigations such as this one can painstakingly assemble cases and suspected deployments, there is another place where signals about spyware use (and abuse) exist: with the spyware companies’ government customers. Our infrastructure analysis uncovered evidence of multiple suspected Paragon customers, and we believe there are more. If a country has been identified as a customer, lawmakers and oversight institutions should not wait until reports of abuse surface to start to ask questions about its use.

Paragon’s Response

Prior to publication, the Citizen Lab sent Paragon Solutions a letter summarizing key findings from our investigation and offered to publish any response they might have in full. Paragon Solutions Executive Chairman John Fleming responded with the following message:

We replied to Mr. Fleming requesting further details on the claimed inaccuracies, and received the following response:

We recognize that Paragon Solutions may have undertaken to protect the identity of their customers, but we also note the long history of mercenary spyware companies like NSO Group asserting similar opacity combined with claims of unspecified inaccuracies to frustrate accountability, deny victims access to justice, and attempt to insulate themselves from harms committed with their technology.

The Citizen Lab welcomes any clarifications Paragon Solutions wishes to provide about the inaccuracies that they have declined to specify, upon reading the full report.

…And Canadian Questions

The Citizen Lab has previously reported on the need for comprehensive reforms to address the growing array of advanced surveillance technologies that are in use in Canada. In November 2022, Canada’s Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy, and Ethics released a report concerning the RCMP’s use of ODITs, which contained numerous recommendations to address a “legislative gap regarding the use of new technological investigative tools.” To date, none of the committee’s law reform recommendations have been implemented by the federal government. The Canadian government is also a signatory to the US-led 2023 Joint Statement on Efforts to Counter the Proliferation and Misuse of Commercial Spyware. However, it has not yet put forward any concrete regulations to prohibit procurement of spyware from firms whose technology presents a risk to national security or is involved in human rights abuses abroad, as the US did in Executive Order 14093. In light of the apparent use of spyware by law enforcement in Ontario, it is essential the Canadian government implement regulations before it becomes yet another democracy with a spyware abuse problem.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge and thank the victims that chose to work with us in this investigation and come forward. Without their participation and engagement this research, like so much accountability work around spyware, simply would not be possible.

Special thanks to Artur Papyan of Cyber HUB-AM for his assistance in this investigation, and Access Now, especially their helpline team, for their exceptional assistance in this case.

Special thanks to our Citizen Lab colleagues Cooper Quintin and Jeffrey Knockel for providing internal peer review and feedback on the report, Adam Senft for writing and editorial assistance, and Alyson Bruce for communications assistance and report editing.

Special thanks to Censys.

Special thanks to Arl3cchino and TNG.

Note: Research Ethics

All research involving human subjects conducted at the Citizen Lab is governed under research ethics protocols reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board. The Citizen Lab does not take general or unsolicited inquiries related to individual concerns regarding information security and cannot provide individual assistance with security concerns.

- We were not able to confirm whether AEI indeed holds a controlling stake in RedLattice (a press release announcing the acquisition only mentions they hold a “significant stake”). ↩

- We note that some fields of the Certificates dataset are incomplete with respect to expired certificates. This can lead to unintuitive behavior when negation is applied over such a field, so we restrict all of our queries involving negation over fields in the Certificates dataset to unexpired certificates. The number of results for this query is thus expected to decline over time. One can obtain complete results by running similar queries against Censys data in BigQuery ↩

- Even though we do not explicitly restrict this query to unexpired certificates, it appears to be implicitly restricted to unexpired certificates, thus the number of results is expected to decline over time. ↩

- Canada is one of several countries (referencing footnote 64) around the world whose authorities use an alternative term for spyware. A 2022 parliamentary study was commissioned to investigate the RCMP’s use of ODITs, given the understanding at that time that ODITs “have technological capabilities similar to Pegasus.” The RCMP described the term ODIT as referring to software that is installed on a targeted computing device that enables the covert collection of electronic evidence from the device. The RCMP stated, at that time, that “RCMP does not use the Pegasus application,” but refused to disclose its source of ODIT technology. ↩