IGF 2013

An Overview of Indonesian Internet Infrastructure and Governance (Part 1 of 4)

This blog post seeks to map out the infrastructure and governance of ICTs in the country, and explores the trends and challenges regarding the right to freedom of expression and access to information, that is grounded in the universal human rights framework.

An Indonesian translation of this post is available here.

Terjemahan dalam bahasa Indonesia dari halaman ini tersedia disini.

Islands of Control, Islands of Resistance: Monitoring the 2013 Indonesian IGF

Terjemahan dalam bahasa Indonesia dari halaman ini tersedia disini.

Read the individual sections here:

- IGF 2013: Islands of Control, Islands of Resistance: Monitoring the 2013 Indonesian IGF (Foreword)

- IGF 2013: Monitoring Information Controls During the Bali IGF (Framing Post)

- IGF 2013: An Overview of Indonesian Internet Infrastructure and Governance (Part 1 of 4)

- IGF 2013: Analyzing Content Controls in Indonesia (Part 2 of 4)

- IGF 2013: Exploring Communications Surveillance in Indonesia (Part 3 of 4)

- IGF 2013: An Analysis of the 2013 IGF and the Future of Internet Governance in Indonesia (Part 4 of 4)

Indonesia, an archipelagic country with a population of over 240 million people, is involved in many regional and international debates on integrating information and communication technology (ICT) in national development. As the largest economy in Southeast Asia, the country’s steps toward ICT development and regulation will have a significant influence on the trajectory of similar efforts in other countries within the region. This blog post seeks to map out the infrastructure and governance of ICTs in the country, and explores the trends and challenges regarding the right to freedom of expression and access to information that are grounded in the universal human rights framework.

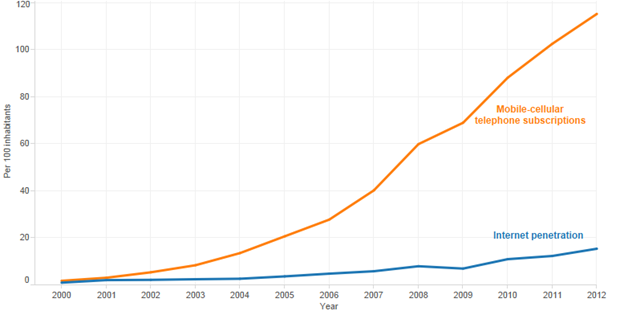

Internet penetration in Indonesia has increased since the beginning of the century from less than 1 percent in 2000 to just over 15 percent in 2011 (or roughly 45 million people). At the end of 2012, that figure was 10 million more, or equivalent to an increase of over 800,000 users every month. A predicted 80 million Indonesian users will be online by the end of 2013. This means that Internet penetration will grow to 33.3 percent. The value of the Internet in Indonesia, as calculated from the amount it will deliver to the gross domestic product (GDP), according to Deloitte Access Economics, is at 1.6 percent of GDP, bigger than liquefied natural gas exports, and it’s growing rapidly. Deloitte Access Economics expects it to grow at three times the pace of the economy, from 1.6 percent of GDP in 2010 to at least 2.5 percent of GDP over the next five years.

Cellular phone penetration has increased at an exponential rate over the same period, from 1.72 to 115.20 cellular phone subscriptions per 100 inhabitants (See Figure 1). A 2011 market report found that 48 percent of users connect to the Internet through mobile devices. Mobile phone subscription in Indonesia reached 290 million in 2012 because people frequently carry two or more devices. The Indonesian government aims to push mobile broadband penetration to 22 percent in 2013, higher than the 8 percent penetration target for fixed broadband.

Indonesia has over three hundred Internet service providers (ISPs), thirty-five of which own network infrastructure. PT Telkom is Indonesia’s largest telecommunications company, with 8.6 million fixed-wire-line customers, 14.2 million fixed-wireless customers, and 107 million cellular customers as of December 2012. PT Indosat is Indonesia’s second-largest cellular operator, with more than 55 million cellular subscribers. Both PT Telkom and PT Indosat were partially privatized in the mid-1990s. The government retains shares in both companies, including over 50 percent ownership in the case of PT Telkom.

In contrast to the agglomeration of ISPs, the growth of Indonesia’s media industry has led to a media oligopoly and the concentration of ownership in the hands of a small number of corporations. Twelve large conglomerates control nearly all of the country’s media channels, including broadcast, print, and online media. For instance, Berita Satu Media Holding, a new media company under the Lippo Group, has established an Internet-Protocol Television (IPTV) BeritasatuTV, online media channel www.beritasatu.com, and also owns a number of newspapers and magazines. A number of these media groups are owned by individuals involved in politics. For example, Aburizal Bakrie is both the chairman of Golkar, one of the country’s biggest political parties, and owner of Visi Media Asia (also known as VIVA), which owns TV stations such as ANTV, tvOne, Vivasky, and Sport One, as well as the online news website VIVA.co.id. Surya Paloh, the founder of a new political party, Nasional Demokrat (NasDem), is the owner of Media Group, which operates the MetroTV station and publishes the newspapers Media Indonesia, Lampung Post, and Borneonews, as well as the tabloid, Prioritas. Such monopoly in the media is made possible by the 2002 Broadcasting Law (Undang-undang Penyiaran), which sets vague limitations on private broadcasting ownership (and, as we will explain, the People’s Representative Council and the Indonesian government are currently drafting a revision to the Broadcasting Law). Ahead of the 2014 general elections, there are concerns that this “conglomeration” may affect the media’s independence.

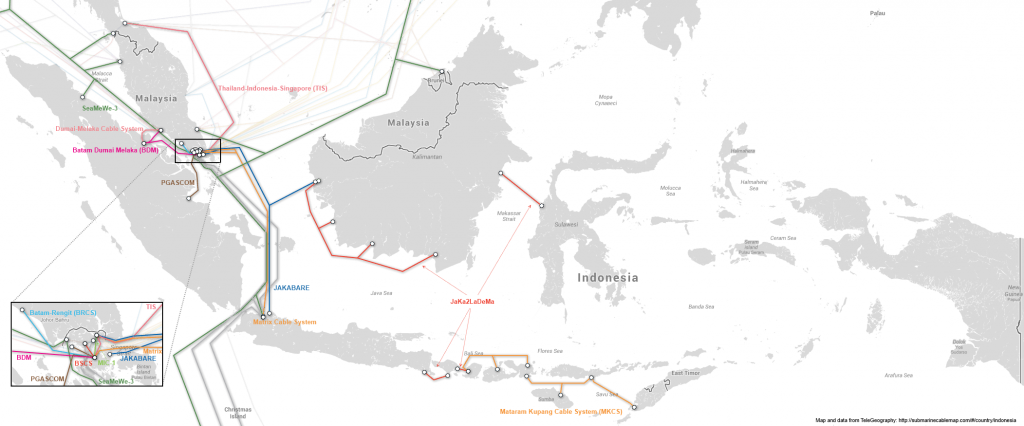

The Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, recognizing the importance of high-speed Internet to economic and social development, launched the Indonesia Connected program to boost connectivity in border and remote areas. The fiber-optic Palapa Ring network is being implemented throughout Indonesia to accommodate this growth. The ministry estimates that construction of the Internet backbone has reached 80 percent, covering Nangroe Aceh Darussalam (Sumatera) Ring, Java-Kalimantan-Sulawesi-Denpasar-Mataram Ring, and Mataram-Kupang Ring. Several companies are involved in this project, including PT Telkom and PT Indosat. Recently, Lippo Group announced that it is partnering with JSAT, Japan’s largest telecommunications company, to increase Internet connectivity in Papua, specifically through the installation of VSAT (very small aperture terminal). The stretch from Manado (Sulawesi) to Papua (5,194 kilometres) will be connected to the fiber-optic network when the project is completed.

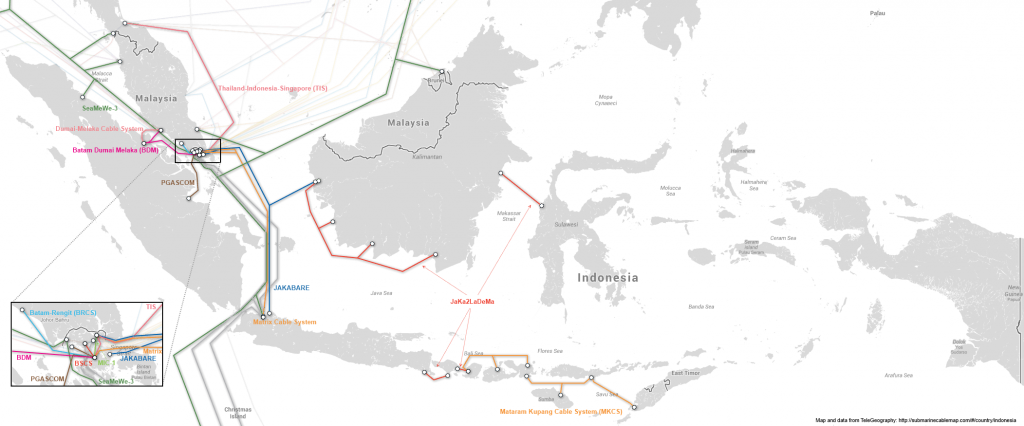

The Palapa Ring project contains 35,280 kilometres of undersea cable. Many of these cables connect to Singapore (see Figure 2), which sits at the crossroads between Asia Pacific and Europe and serves as a major hub for submarine cables used for Internet and telecommunications infrastructures. Citizen Lab’s partner organization, Privacy International, has conducted research on surveillance technology providers, whose systems include subsea cable-tapping technology. According to the Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), information disclosed by US whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed that the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) collects all data transmitted to and from the United Kingdom and Northern Europe via one of Indonesia’s submarine cables, the SEA-ME-WE-3, which is the longest optical submarine cable in the world with landing points in Medan and Jakarta, Indonesia. Australian intelligence sources also told Fairfax Media, which owns the SMH, that Singaporean intelligence cooperates with Australia in accessing and sharing communications carried by the cable.

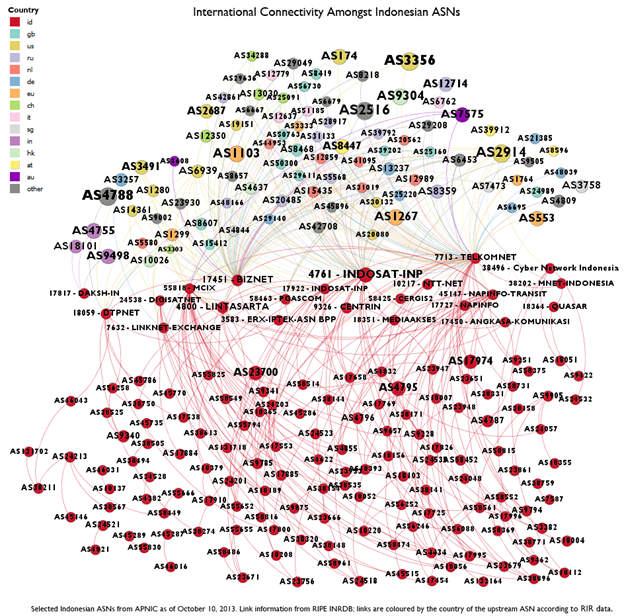

Indonesia does not have a centralized Internet infrastructure and has several links to overseas networks. The Indonesia Internet Exchange (IIX), the country’s first Internet exchange point (IXP), is maintained by the Association of Indonesian Internet Service Providers (APJII) (See Figure 3). The country’s second IXP, OpenIXP, is operated by the Indonesia Data Center (IDC). Indonesian government regulation mandates that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) must subscribe their IP transit from the network access provider (NAP) as global upstream. The IXPs, therefore, serve only local/domestic function between Indonesian ISPs.1

Figure 4 shows various Indonesian, as well as foreign, Autonomous Systems (ASes): networks that are under the administration of a particular entity or authority. The middle layer of nodes in the diagram (with both names and numbers) represents Indonesian networks that have upstream connectivity to foreign networks. The variety of networks and number of links to these foreign networks indicates a lack of centralization. This dispersed decentralized network may be what caused Renesys, an Internet intelligence provider, to classify Indonesia in 2012 as “likely to be extremely resilient to Internet disconnection.”

Despite its impressive growth and numerous small and large ISPs, Indonesia’s ICT development has lagged behind many of its regional neighbours’ ICT growth. For example, Malaysia’s Internet penetration rate was close to 66 percent in 2012, while the percentage of individuals using the Internet in Singapore was 74 percent in the same year. LIRNEasia, a regional think tank focusing on ICT policy and regulation in the Asia-Pacific region, places this technological development gap in the context of political instability and Indonesia’s economic stagnation during the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s. LIRNEasia further names the limited use of English in Indonesia, a lack of access to telecommunication infrastructure in rural areas, the high cost of connectivity to the international backbone, and inadequate government regulation as contributing factors to Indonesia’s low ICT use. In addition, according to the Indonesian Internet Governance Forum (ID-IGF), the low level of bandwidth and computer penetration in Indonesia has contributed significantly to the challenge of increasing Internet penetration in the country.

Regulatory Bodies

Ministerial duties associated with the regulation of information technology fall under the auspices of the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology (MCIT).The ministry defines part of its function as the “formulation of national policy, policy implementation, and technical policies in the field of communication and informatics, including the postal, telecommunications, broadcasting, information technology and communications, multimedia services and the dissemination of information.” In 2005, the MCIT took control of the Directorate General of Post and Telecommunication (DGPT). According to its website, the DGPT has three functions:

The first function covers all general and operational aspects, which is implemented through licensing and other requirements. The second function covers all aspects of surveillance and scrutiny to make sure that posts and telecommunications are conducted within the legal framework, while the third function deals with supervision to the operators as well as enforcement of law regarding their operations.

Another key government department is the Indonesian Telecommunications Regulatory Body (Badan Regulasi Telekomunikasi Indonesia, BRTI). The BRTI is responsible for issuing licenses, resolving disputes, and advising government on telecommunication policy issues. However, its responsibilities vis-à-vis DGPT are not clearly defined. Although the BRTI was intended to be an independent regulator, the agency has been criticized for its lack of independence because it is chaired by the DGPT, which is part of MCIT.

Laws and Regulations

The Indonesian Constitution (Undang Undang Dasar (UUD) 1945)

The 1945 constitution was amended four times between 1999 and 2002. Before these amendments, the constitution did not explicitly affirm human rights. For instance, articles 27 (1 and 2) and 28 asserted only the existence of the principle of equality before law, freedom of assembly, and freedom of speech. It was after the amendments were made that the constitution stipulates a number of articles that explicitly affirm human rights are honoured and guaranteed. Ten articles were incorporated into the constitution (articles 28A, 28B, 28C, 28D, 28E, 28F, 28G, 28H, 28I and 28J), proving that Indonesia has adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Deklarasi Universal tentang Hak Asasi Manusia).2

Decree No. XVII/MPR/1998 and Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights

This is how the Decree of the Consultative Assembly (TAP MPR) No. 17/MPR/1998 concerning human rights protects the right to freedom of expression:

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom to express his/her opinions and convictions based on their conscience (Article 14);

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association, assembly, and expression opinion (Article 19);

- Everyone shall have the right to communicate and receive information for his/her personal development and social environment (Article 20);

- Everyone shall have the right to seek, obtain, posses, keep, process, and convey information by utilising all kinds of available channels (Article 21); and

- The right of citizens to communicate and obtain information is guaranteed and protected (Article 42).

Furthermore, Indonesia adopted Law No. 39 of 1999 on Human Rights. The preamble to this law states that Indonesia, as a United Nations (UN) member state, has moral and legal responsibilities to honour and implement the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international instruments on human rights. The law also stipulates that everyone has the right to express his or her opinion in public (article 25).

Religion

Religion is a key factor affecting the regulation of freedom of expression in Indonesia. As the world’s largest majority Muslim country, the voices of those who believe in a more conservative brand of Islam have influenced discussions ranging from the social to political arenas and have given rise to strict legislation governing what’s considered acceptable content or speech.

The passing of laws with harsh, punitive legal measures, as outlined below, and the demand for telecommunication companies like BlackBerry and ISPs to filter out pornographic content are indicative of increasing pressure from conservative groups, and the lack of regard for the protection of the people’s right to freedom of expression and freedom of information, despite these rights being included in the Indonesian Constitution.

Passing laws with harsh, punitive legal measures and demanding telecommunication companies like BlackBerry and ISPs to filter out pornographic content indicate increasing pressure from conservative groups, and the lack of protection of people’s right to freedom of expression and freedom of information, despite these rights being included in the Indonesian constitution.

Indonesia’s free press, dynamic political process, and vibrant civil society have exerted pressure on the government to respect these rights (and will continue to), but there needs to be sustained international support to ensure that the government works in as transparent and accountable a manner as possible.3

Law No. 36 of 1999 on Telecommunications

Telecommunications services in Indonesia used to be provided by a string of state-owned companies. But recent reforms have attempted to create a regulatory framework that promotes competition and accelerates the development of telecommunications facilities and infrastructure. The enactment of Law No. 36 of 1999 on Telecommunications, which replaced Law No. 3 of 1989 on Telecommunications, provided the framework for a major deregulation of the Indonesian telecommunications sector to unfold. These deregulation measures are reflected in its commitments under the WTO Agreement on Basic Telecommunications that entered into force in February 1998, which means that the country committed itself to review its current policy.

This law does not regulate e-commerce or other specific receiving or sending information through the Internet. However, in the definition of telecommunication, one can see that although it’s not explicitly mentioned, the transmission of information through the Internet is covered by the law. The definition of telecommunication in article 1(1) of the law is “any broadcasting, sending and or receiving from any information in the form of sign, code, word, picture, sound, and tone through cable system, fiber optic system, radio, or other electromagnetic system.”4 Furthermore, article 4(1) mentions that “the state has authority on telecommunication and the government has power to its development,”5 and therefore, the development of the Internet can be expected to fall under the government’s purview.

Law No. 11 of 2008 on Electronic Information and Transactions Law

Law No. 11 of 2008 on Electronic Information and Transactions (EIT) was adopted on 21 April 2008. It is the first cyber law in the country and the main instrument for the regulation of online content.

Chapter 7 of the EIT law lists all prohibited acts, which include knowingly and without authority distributing, transmitting, or causing to be accessible in electronic form records containing:

- Material against propriety (article 27(1));

- Gambling material (article 27(2));

- Material amounting to affront and/or defamation (article 27(3)); and

- Extortion and/or threats (article 27(4)).

In 2013, the MCIT said that they will prioritize a revision of the law. Of particular concern is article 27(2) regarding defamation. Gatot S. Dewa Broto, the spokesperson for the MCIT, said that many have judged the penalty of up to six years’ imprisonment and fines of up to IDR 1 billion (approximately USD 106,000) as being too harsh,6 especially because it’s more severe than the provisions contained in the penal code, which specified the penalty of up to nine months’ imprisonment. Our blog post on content control elaborates on how this law, in conjunction with other laws such as Law No. 44 of 2008 on Pornography (the Anti-Pornography Law), the penal code’s articles 207-208, 310-21, and 335 on defamation, and several Indonesian laws prohibiting blasphemy or “defamation of religions,” including Law No. 1/PNPS/1965 (the Presidential Decision), is used for content regulation.

The EIT law also contains provisions on interception and wiretapping in article 31(4), which calls for the government to issue a regulation (Peraturan Pemerintah, PP) on the matter. Following a request for judicial review submitted by Anggara, Supriyadi Widodo Eddyono, and Wahyudi Djafar from the Institute of Policy Research and Advocacy (ELSAM), the Constitutional Court annulled article 31(4) because it contradicted articles 28G(1) and 28J(2) of the 1945 constitution. Furthermore, because wiretapping imposes a limit on individual privacy rights, which are a basic human right, the court ruled that it has to be regulated by legislation (Undang Undang) and not merely by government regulation.

Draft Law on Telematics Convergence

To prepare for the convergence of traditional media and new media, the MCIT drafted the Telematics Convergence Law (RUU Konvergensi Telematika), which the government proposed as an overarching law to the Telecommunications Act, the EIT Law, and the Broadcasting Law governing telecommunications and ICT in Indonesia.

Telematics is defined broadly as any kind of application that uses the Internet to transmit (e.g., voice, images, data, content-based services, e-commerce, as well as other services provided through applications). The fact that the government drafted a law with such a broad definition of what it is supposed to regulate caused concerns that it will be used to control online content and information. After widespread criticism, the draft Telematics Convergence Law was shelved indefinitely by the MCIT. As an alternative, the People’s Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR) initiated a draft Broadcasting Law and its deliberation process is underway. If the law passes, a Convergence Law will no longer be necessary.

Draft Law on Interception Mechanism

In Indonesia, there are at least twelve laws, two government regulations, and two ministerial regulations that outline the practice of wiretapping by state institutions in the name of law enforcement. In January 2013, Gatot S. Dewa Broto, the spokesperson for Indonesia’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, stated that the government as a whole is preparing a draft law on interception mechanisms (RUU Tata Cara Intersepsi). Our blog post on Internet surveillance elaborates further on the legal and operational problems surrounding wiretapping in Indonesia.

Draft Law on Information Technology Criminal Offense

The People’s Representative Council (DPR) drafted the Information Technology Criminal Offence Law (RUU Tindak Pidana Teknologi Informatika, TIPITI) as a response to the proliferation of cybercrime in Indonesia. When it was first announced to the public, the bill was considered to be a major threat to freedom of expression because many people considered its provisions to be too broad, and to contain worse penalties than those in the controversial Electronic Information and Transactions Law (e.g., up to thirty years in prison and fines up to USD 1,060,000, according to the 2009 draft). Although the bill was considered to be a priority bill in the 2010 National Legislation Program, it was not until 2012 that it was finalized due to pressure from the MCIT. At the time of publication, the law is still waiting to be passed.

Cyber and Regional Security Initiatives

Like almost all countries today, Indonesia recognizes that cyber security has become a major priority. Indonesia has become a full member of the Asia Pacific Computer Emergency Response Team (APCERT) and FIRST (Forum for Incident Response and Security Team) and a full member and founder of the OIC-CERT (Organization of the Islamic Conference-Computer Emergency Response Team). As of 2010, the draft law on cybercrime and draft law on the ratification of the EU Convention on Cybercrime have been listed in the national legislation program as priorities to be discussed. Whatever the components of that cyber-security strategy will be, it will invariably affect the character of information controls. Indonesia’s cyber-security strategy will reflect both contests among domestic interest groups and stakeholders, as well as the influence of regional and international norms and Indonesia’s participation in regional and other security forums. In particular, the regional alliance — the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Indonesia is a founding member — will be a major influence and source of norms and practices. In September 2013, ASEAN announced that a cyber-security agreement was reached among member states in which Indonesia and other members will jointly develop a mechanism to combat cyber attacks, coordinate trainings, and share threat information — practices that have already begun among some of the region’s CERTs. Along with our colleagues in the region, we will be monitoring these developments closely, especially in light of the impending arrival of the ASEAN Economic Community in 2015. We intend to issue reports on regional cyber-security initiatives in Asia.

Conclusion

Indonesian information controls cannot be understood without considering the broader social, political, and legal context and the ICT environment within which they are embedded. The nature and character of information controls depend on the market structure of ISPs, telecommunication companies, informal relations, and practices among stakeholders, especially a diverse and politically active civil society, and the legal and policy structures that frame them all. With this backdrop in mind, in two related posts, here and here, we elaborate on the research we undertook while attending the 2013 IGF on content controls and surveillance in Indonesia.

Footnotes

1 PowerPoint Presentation by Harijanto Pribadi, Department Head of IIX APJII, https://citizenlab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/IIX-APJII2012-APNIC34-Final.pptx

2 Totok Sarsito, “The Indonesian Constitution: Why it was amended,” Journal of International Studies, 3 (2007), http://www.myjurnal.my/public/issue-view.php?id=2125&journal_id=217

3 Kikue Hamayotsu, “The Limits of Civil Society in Democratic Indonesia: Media Freedom and Religious Intolerance”, Journal of Contemporary Asia, 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2013.780471

4 Article 1 (1) of Law No. 36/1999, http://dittel.kominfo.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/36-TAHUN-1999.pdf

5 Article 4 (1) of Law No. 36/1999, http://dittel.kominfo.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/36-TAHUN-1999.pdf

6 For more information on Criminal Defamation Law, please see Human Rights Watch’s “Turning Critics into Criminals: The human rights consequences of Criminal Defamation Law in Indonesia.” http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/indonesia0510webwcover.pdf